From APF-1 to Ubiquitin: The Discovery of the Molecular Kiss of Death and Its Impact on Biomedicine

This article chronicles the foundational discovery of ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), later identified as the universal protein ubiquitin, which revolutionized the understanding of intracellular protein degradation.

From APF-1 to Ubiquitin: The Discovery of the Molecular Kiss of Death and Its Impact on Biomedicine

Abstract

This article chronicles the foundational discovery of ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), later identified as the universal protein ubiquitin, which revolutionized the understanding of intracellular protein degradation. We explore the seminal biochemical and genetic research that elucidated the ubiquitin-proteasome system, from its initial characterization in rabbit reticulocyte lysates to the identification of the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes key methodological approaches, troubleshooting insights from early experiments, and the validation of ubiquitin's role as a central regulator in cell cycle control, DNA repair, and disease pathogenesis. The article concludes with an examination of the system's profound implications for developing novel therapeutic strategies, including targeted protein degradation.

The Serendipitous Discovery of APF-1: Unraveling the Mechanism of ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

For much of the mid-20th century, intracellular protein degradation was largely regarded as a nonspecific, end-process managed by the lysosomal system. However, a fundamental biochemical paradox challenged this simplistic view: the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is exergonic, yet experimental evidence consistently demonstrated that intracellular proteolysis required substantial metabolic energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This energy requirement made no thermodynamic sense for a process that should release energy, suggesting the existence of a more complex, energy-dependent regulatory mechanism [1] [2].

The collaboration between Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose was uniquely positioned to resolve this paradox. Their work, which would later earn them the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, began with a simple biological curiosity about this energy requirement and ultimately led to the discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, fundamentally changing our understanding of cellular regulation [1] [3].

Historical Context: Key Observations Preceding Discovery

The intellectual journey toward understanding energy-dependent proteolysis rested on critical foundational discoveries made between the 1930s and 1970s, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Foundational Discoveries Preceding the Ubiquitin System

| Time Period | Key Observation | Principal Investigators | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939-1942 | Dynamic state of body proteins | Schoenheimer et al. | Established that cellular proteins undergo continuous synthesis and degradation [2] |

| 1953 | ATP dependence of proteolysis | Simpson | First demonstration of the energy paradox in protein degradation [1] [3] |

| Mid-1950s | Discovery of lysosome | de Duve | Identified the primary degradative organelle [2] |

| 1970s | Non-lysosomal ATP-dependent proteolysis | Goldberg, Etlinger et al. | Showed enucleated reticulocytes (lacking lysosomes) still exhibited ATP-dependent proteolysis [1] [3] |

The limitations of the lysosomal hypothesis became increasingly apparent through several lines of evidence. Researchers observed that different proteins exhibited vastly different half-lives within the same cell, and the stability of a single protein could vary significantly under different physiological conditions. This exquisite specificity could not be adequately explained by the presumably nonspecific lysosomal degradation process [2].

Experimental Breakthrough: The Reticulocyte System and APF-1

Critical Methodology: A Tractable Biochemical Assay

The pivotal technical breakthrough came with the adoption of the reticulocyte lysate system, which lacks lysosomes yet exhibits robust ATP-dependent proteolysis. This system allowed for biochemical fractionation that would have been impossible in whole-cell systems containing active lysosomes [1] [3].

Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose employed a systematic fractionation approach:

- ATP depletion: Pre-depletion of endogenous ATP from reticulocyte lysates was crucial for observing the APF-1 requirement

- Biochemical fractionation: Separation of lysate components using anion-exchange chromatography (DEAE-cellulose)

- Functional reconstitution: Combining fractions to restore ATP-dependent proteolytic activity [1] [2]

Table 2: Key Fractions Isolated from Reticulocyte Lysates

| Fraction | Properties | Required Component Identified | Later Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction I | Heat-stable | ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1) | Ubiquitin [1] [3] |

| Fraction II | High molecular weight, ATP-stabilized | APF-2 | 26S Proteasome (core protease) [1] |

| Additional Factors | Required for full activity | Not initially characterized | E1, E2, E3 enzymes [3] |

The Discovery of Covalent Conjugation

The seminal experimental insight came when the researchers investigated the mechanism of APF-1. In a series of elegant experiments published in 1980, they made an astounding observation: APF-1 formed covalent conjugates with multiple proteins in Fraction II in an ATP-dependent manner [1] [3].

Key experimental evidence included:

- Radiolabeling studies: Using ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1, they demonstrated ATP-promoted formation of high molecular weight complexes

- Chemical stability: The conjugates survived high pH (NaOH) treatment, indicating covalent bonds

- Reversibility: The association was reversed upon ATP removal

- Substrate targeting: Authentic proteolytic substrates were heavily modified with multiple APF-1 molecules [1]

This covalent attachment represented a completely novel mechanism for targeting proteins for destruction and explained the puzzling ATP requirement—energy was needed not for proteolysis itself, but for the tagging process that preceded it [1].

APF-1 to Ubiquitin: Connecting the Pieces

The connection between APF-1 and the previously known protein ubiquitin came through collaborative insight. Researchers noted the similarity between APF-1 conjugation and the known modification of histone H2A by a small protein called ubiquitin, first discovered by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized by Goldknopf and Busch [1].

Comparative analysis revealed:

- Structural identity: APF-1 was biochemically identical to ubiquitin

- Conservation: Ubiquitin was already known to be widely distributed and highly conserved

- Modification chemistry: Both systems used isopeptide bonds between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and ε-amino groups of lysine residues in target proteins [1]

This connection provided immediate historical context and suggested that the researchers had discovered the physiological function of this previously enigmatic protein.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway: Mechanism Revealed

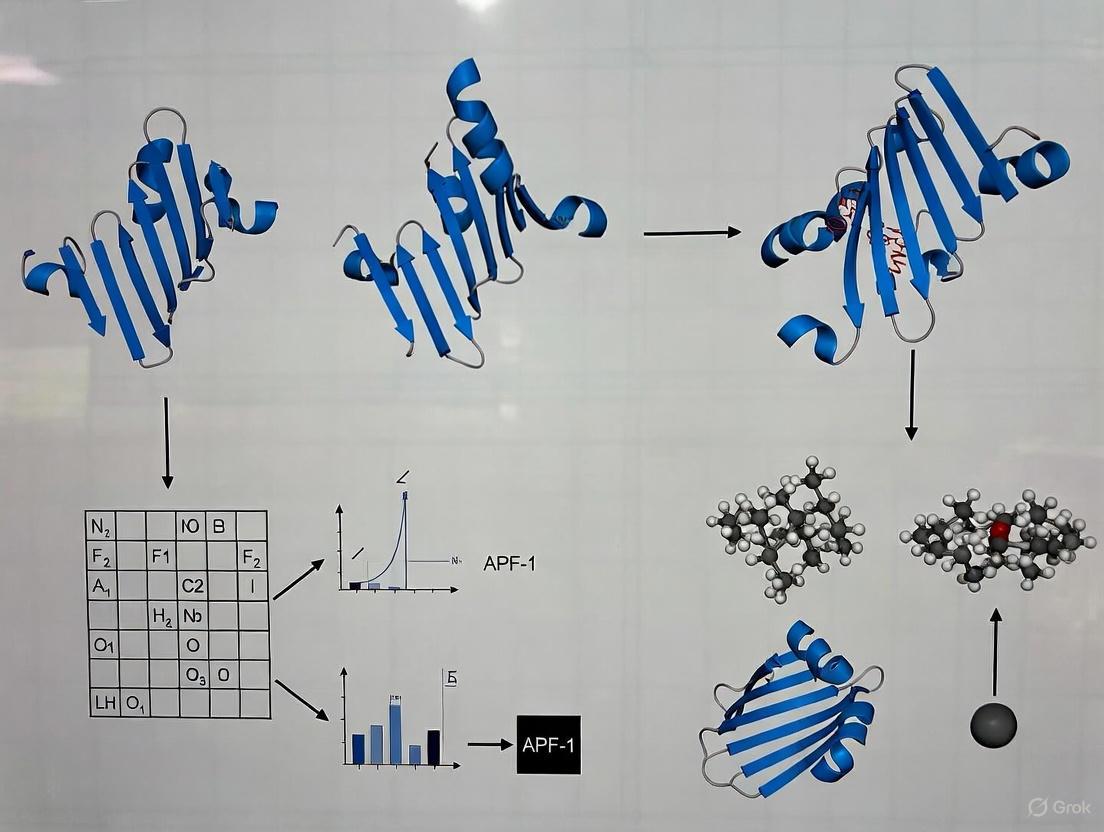

The core mechanism of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis involves a highly coordinated enzymatic cascade that explains the original energy paradox, as visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The process resolves the energy paradox by requiring ATP only for the initial tagging phase, not the proteolysis itself.

The Enzymatic Cascade

The ubiquitin conjugation system employs three key enzymes that work sequentially:

E1 Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme:

- Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction

- Forms a high-energy thioester bond with ubiquitin

- Single or few E1 enzymes in most cells [4]

E2 Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme:

- Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1

- Carries ubiquitin via thioester linkage

- Multiple E2 enzymes with varying specificities [4]

E3 Ubiquitin Ligase:

Polyubiquitin Chain Recognition

A critical finding was that proteolytic targeting requires polyubiquitination—the attachment of a chain of at least four ubiquitin molecules linked through lysine 48 (K48). This specific chain architecture serves as the recognition signal for the 26S proteasome [1] [5].

The 26S proteasome itself consists of:

- 20S core particle: Contains the proteolytic active sites

- 19S regulatory particle: Recognizes polyubiquitinated substrates, removes ubiquitin chains, and unfolds substrates for degradation [5] [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteolysis

| Reagent/Condition | Function in Research | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | ATP-dependent proteolysis system | Foundational cell-free system for biochemical fractionation [1] [3] |

| ATP Depletion | Critical pretreatment step | Revealed APF-1/ubiquitin requirement by preventing pre-conjugation [1] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (MG-132) | Blocks proteasomal degradation | Allows accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins for detection [4] |

| ²⁵I-APF-1/Ubiquitin | Radioactive tagging | Enabled detection and characterization of covalent conjugates [1] |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Immunodetection | Western blot, immunoprecipitation of ubiquitinated proteins [4] |

| DEAE-Cellulose Chromatography | Anion-exchange fractionation | Separated Fraction I (APF-1) and Fraction II (APF-2) [1] [2] |

Legacy and Implications: From Basic Mechanism to Therapeutic Applications

The discovery of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis represents a classic example of how investigating a fundamental biochemical paradox can yield transformative biological insights with far-reaching applications.

The ubiquitin system has proven to be every bit as important as phosphorylation in regulating eukaryotic cell physiology, controlling virtually all cellular processes including:

- Cell cycle progression and division

- Signal transduction

- DNA repair

- Quality control of protein folding [1] [3]

The therapeutic implications are profound, leading to the development of targeted protein degradation technologies such as:

- PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras): Bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target proteins

- Molecular glues: Compounds that induce proximity between E3 ligases and target proteins

- Several candidates currently in clinical trials for cancer and other diseases [6] [7]

These applications directly descend from the fundamental understanding of how cells naturally use the ubiquitin system to selectively target proteins for destruction, a process initiated by the resolution of the energy paradox of ATP-dependent intracellular protein degradation.

This technical guide details the foundational methodology and experimental protocols that led to the discovery of a heat-stable essential factor, initially termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1), from rabbit reticulocyte lysates. This work, pioneered by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose, resolved the long-standing enigma of energy-dependent intracellular proteolysis and laid the biochemical groundwork for the discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system [1] [8]. The identification of APF-1, later recognized as the protein ubiquitin, introduced a novel paradigm of post-translational regulation through covalent protein conjugation [9] [3]. This document provides an in-depth reconstruction of the critical fractionation experiments, serving as an essential resource for researchers investigating protein degradation and its profound implications in cellular regulation and human disease.

Prior to the 1980s, the biochemical mechanisms governing intracellular protein degradation were poorly understood. A key metabolic puzzle was the ATP dependence of proteolysis—the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is an exergonic process, and there was no apparent thermodynamic requirement for energy input [1] [8]. Early work by Simpson in 1953 had established this energy requirement, but the mechanism remained elusive for nearly three decades [1] [3]. The prevailing assumption was that degradation occurred within lysosomes, but accumulating evidence suggested the existence of a major, non-lysosomal ATP-dependent proteolytic pathway [8].

A critical breakthrough came with the development of a cell-free system from rabbit reticulocytes by Etlinger and Goldberg in 1977 [1] [9]. Reticulocytes, which are devoid of lysosomes, provided an ideal model because they rapidly degrade abnormal proteins in a soluble, ATP-dependent manner [8] [9]. This system enabled the application of classical biochemical fractionation techniques to dissect the components of the proteolytic machinery, setting the stage for the discovery of APF-1.

Core Experimental Breakthrough: Fractionation and the Discovery of APF-1

The Hershko laboratory utilized the reticulocyte lysate system to systematically identify the essential components required for ATP-dependent proteolysis. The pivotal experimental strategy involved separating the lysate into functionally distinct biochemical fractions.

Initial Fractionation on DEAE-Cellulose

The foundational step was the separation of the reticulocyte lysate using anion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-cellulose [10] [9]. This process yielded two key fractions:

- Fraction I: The unadsorbed material, containing hemoglobin and other proteins.

- Fraction II: The adsorbed material, eluted with a high-salt buffer [9].

Individually, neither fraction demonstrated significant ATP-dependent proteolytic activity. However, when recombined, ATP-dependent protein degradation was reconstituted, indicating that both fractions contained essential components of the system [9].

Identification and Characterization of a Heat-Stable Factor (APF-1)

Further analysis of Fraction I revealed that its essential component was a low-molecular-weight, heat-stable polypeptide [9]. This factor was named APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [1] [9]. The following table summarizes the key properties of APF-1 established during its initial identification.

Table 1: Characteristics of the Isolated APF-1 (Ubiquitin)

| Property | Experimental Observation | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Stability | Remained active after heating to 80-100°C [9]. | Facilitated easy purification and separation from the vast majority of cellular proteins. |

| Molecular Size | Small polypeptide; later identified as 76-amino acid ubiquitin [1] [9]. | Distinguished it from larger, canonical proteases. |

| Ubiquity | Later found to exist in all eukaryotic cells [9]. | Suggested a fundamental, conserved cellular role, not a specialized function. |

| Functional Requirement | Absolutely required for ATP-dependent proteolysis in the fractionated system [10] [9]. | Established it as a central, non-redundant component of the degradation machinery. |

Key Experimental Protocols

The following section details the core methodologies that enabled the discovery and functional characterization of APF-1.

Protocol 1: Fractionation of Reticulocyte Lysate via DEAE-Cellulose

This protocol describes the initial separation of the reticulocyte lysate into its active fractions [9].

- Lysate Preparation: Obtain rabbit reticulocyte lysate. Commercial lysates are often treated with micrococcal nuclease to degrade endogenous mRNA and reduce background protein synthesis [11].

- Chromatography: Apply the clarified lysate to a column of DEAE-cellulose resin equilibrated in a low-salt buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5).

- Fraction I Collection: The flow-through fraction, which does not bind to the resin, is collected. This is Fraction I and contains hemoglobin and the heat-stable APF-1.

- Fraction II Elution: Proteins adsorbed to the resin are eluted using a buffer containing a high salt concentration (e.g., 0.2-0.3 M NaCl). This eluate is Fraction II.

- Dialysis and Storage: Dialyze Fraction II against a low-salt buffer to remove excess salt. Both fractions can be stored at -80°C for future reconstitution experiments.

Protocol 2: Demonstration of ATP-Dependent APF-1 Conjugation

A critical experiment showed that APF-1 was not merely a cofactor, but became covalently attached to other proteins in an ATP-dependent reaction [10] [3].

- Reaction Setup: Incubate iodinated APF-1 (¹²⁵I-APF-1) with Fraction II in the presence of an ATP-regenerating system (ATP, Mg²⁺, phosphocreatine, creatine phosphokinase).

- Controls: Include control reactions lacking ATP, or containing non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs, UTP, or GTP, which were shown to be inactive [10].

- Inhibition Control: A separate reaction should include N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), a thiol alkylating agent, which inhibits conjugation [10].

- Analysis: Stop the reaction and analyze the products by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by autoradiography.

- Expected Result: In the complete system with ATP, high molecular weight conjugates of ¹²⁵I-APF-1 will be observed, demonstrating covalent linkage. These conjugates will be absent in the no-ATP and NEM controls [10].

Protocol 3: Confirming the Covalent Nature of Conjugates

The stability of the APF-1-protein linkage was tested against various denaturing conditions [10].

- Heat Denaturation: Boil the conjugation reaction mixture in SDS sample buffer before electrophoresis.

- Alkali and Acid Treatment: Incubate conjugates with NaOH (e.g., 0.1 M) or HCl (e.g., 0.1 M).

- Reducing Agents: Treat conjugates with agents like 2-mercaptoethanol to break disulfide bonds.

- Result: The APF-1 conjugates remained stable under all these conditions, providing strong evidence that the bond was a non-peptide, covalent isopeptide bond [10] [1].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the experimental process that led from the initial biological observation to the definitive confirmation of covalent conjugation.

Data Presentation and Analysis

The experimental findings were quantifiable, providing robust support for the proposed model.

Quantitative Requirements for APF-1 Conjugation

The conjugation of APF-1 to proteins in Fraction II displayed specific biochemical requirements, mirroring the characteristics of the overall ATP-dependent proteolytic process [10].

Table 2: Biochemical Requirements for APF-1 Conjugation

| Parameter | Requirement | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | ATP | UTP and GTP were inactive [10]. |

| Divalent Cation | Mg²⁺ | Chelating agents inhibited conjugation [10]. |

| Inhibitors | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Thiol alkylation inhibited conjugation, implying a crucial cysteine residue in the enzymatic machinery [10]. |

| ATP Concentration | Low concentrations (e.g., 0.1-0.2 mM) | Saturation occurred at low ATP levels, similar to the proteolysis reaction [10]. |

| Stability of Conjugates | Covalent and stable to SDS, heat, alkali, acid, and reducing agents. | Conjugates persisted through SDS-PAGE and various denaturing treatments [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs the key reagents and their critical functions in the fractionation and conjugation experiments.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Reticulocyte Fractionation and APF-1 Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experimental Process |

|---|---|

| Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate | Source of the ATP-dependent proteolysis system; chosen for its lack of lysosomes and high degradation activity [11] [9]. |

| DEAE-Cellulose Resin | Anion-exchange medium for the primary fractionation of the lysate into complementary Fractions I and II [10] [9]. |

| ATP-Regenerating System (ATP, Mg²⁺, Phosphocreatine, Creatine Phosphokinase) | Maintains a constant, high level of ATP in incubation mixtures, which is crucial for both proteolysis and conjugation assays [10] [11]. |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Thiol-reactive agent used to inhibit conjugation, thereby demonstrating the involvement of a cysteine-dependent enzymatic step (e.g., E1 activating enzyme) [10]. |

| Radiolabeled APF-1 (e.g., ¹²⁵I-APF-1) | Tracer for sensitive detection and analysis of APF-1 conjugation to high molecular weight proteins via SDS-PAGE and autoradiography [10] [3]. |

| Heat Block (80-100°C) | Used to denature and remove the majority of heat-labile proteins from Fraction I, allowing for the purification and concentration of the heat-stable APF-1 [9]. |

The Pathway to Degradation: A Modern Interpretation

While the initial studies identified the covalent conjugation of APF-1, subsequent work by Hershko, Rose, and others rapidly elucidated the enzymatic pathway and its purpose. We now understand that APF-1 is ubiquitin, and its conjugation is a multi-step process that marks proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome. The following diagram illustrates this pathway, with the components discovered in the featured experiments highlighted.

The key discovery that APF-1/ubiquitin forms covalent conjugates corresponds to the Ligation and Polyubiquitination stages of this pathway. The initial experiments with Fraction II effectively captured the combined activity of the E1, E2, and E3 enzymes.

Discussion and Impact on Modern Biology

The simple yet powerful experiments detailing the fractionation of reticulocyte lysates and the identification of APF-1 had revolutionary implications.

- Paradigm Shift in Post-Translational Modification: The discovery established that covalent attachment of an entire protein (ubiquitin) could serve as a regulated signal, akin to phosphorylation, dramatically expanding the understanding of post-translational control [1].

- Resolution of the Energy Dependence: The requirement for ATP was explained by the multi-enzyme cascade needed to activate and conjugate ubiquitin, not by the proteolysis step itself [1] [3].

- Foundation for the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: This work directly led to the characterization of the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade and the recognition of the 26S proteasome as the ultimate protease [12] [3]. The "smear" of high molecular weight conjugates observed on gels was later understood to represent polyubiquitin chains that serve as the degradation signal [1] [9].

- Broad Physiological and Pathological Significance: The ubiquitin system is now known to be involved in nearly all aspects of cellular function, including cell cycle regulation, signal transduction, DNA repair, and immune response [8] [3]. Aberrations in the system are implicated in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and infectious diseases, making the core components identified in these early studies prime targets for therapeutic drug development [8].

The fractionation of reticulocyte lysates, leading to the identification of the heat-stable APF-1, stands as a classic example of how rigorous biochemistry can uncover fundamental biological principles. The methodology outlined here—from system establishment and fractionation to functional conjugation assays—provided the incontrovertible evidence for a novel protein-based tagging mechanism. This foundational research, recognized by the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, unlocked the field of ubiquitin research, revealing a complex and essential language of cellular regulation that continues to be deciphered by scientists and leveraged by drug development professionals today.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), a seminal discovery in the understanding of regulated intracellular proteolysis. We detail the experimental characterization of APF-1 that revealed its identity as ubiquitin and its crucial function in forming covalent conjugates with protein substrates—the fundamental mechanism underlying targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells. Within the broader context of heat-stable protein research, the elucidation of APF-1's role established the biochemical foundation for the ubiquitin-proteasome system, a pathway essential for cellular regulation and a prime target for therapeutic intervention. This work summarizes key quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and the enzymatic cascade that defines this critical regulatory system.

The discovery of APF-1 emerged from investigations into a fundamental biochemical paradox: why did intracellular protein degradation require ATP despite the exergonic nature of peptide bond hydrolysis? This energy dependence, first observed by Simpson in 1953 [1], suggested a complex regulatory mechanism beyond simple lysosomal proteolysis or the action of conventional ATP-dependent proteases.

In the late 1970s, the laboratory of Avram Hershko, utilizing a biochemically tractable rabbit reticulocyte lysate system, resolved this ATP-dependent proteolytic activity into essential fractions [1]. Fraction I contained a single, heat-stable polypeptide component deemed essential for the reaction, which they designated ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) [1] [13]. This small, heat-stable protein would later be recognized as the central player in a novel post-translational modification system.

Experimental Characterization of APF-1 and its Conjugates

Key Experimental Findings

The initial characterization of APF-1 involved a series of elegant experiments that defined its unique behavior and mechanism of action. Researchers observed that upon incubation with Fraction II (containing the remaining enzymatic machinery) and ATP, iodinated APF-1 (¹²⁵I-APF-1) was promoted to high molecular weight forms [1]. Surprisingly, this association was found to be covalent and stable to high pH treatment, indicating a robust chemical linkage rather than a non-covalent complex [1]. This covalent modification occurred on multiple endogenous proteins in the reticulocyte lysate, as visualized by SDS-PAGE autoradiography.

A critical breakthrough came when APF-1 was shown to form multiple conjugates with model protein substrates like lysozyme, a known substrate for ATP-dependent degradation [14]. Analysis of the molecular weights and radioactivity ratios of these bands revealed that they consisted of lysozyme molecules with increasing numbers of APF-1 polypeptides attached [14]. This multi-valent conjugation was proposed as a potential targeting signal for proteolysis.

The Identity of APF-1 Revealed as Ubiquitin

In 1980, Wilkinson, Urban, and Haas demonstrated that APF-1 was identical to the previously characterized protein ubiquitin [15] [13]. The evidence supporting this identity was compelling across multiple experimental dimensions, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Experimental Evidence Establishing APF-1 as Ubiquitin

| Experimental Parameter | APF-1 Characteristics | Ubiquitin Characteristics | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophoretic Mobility | Co-migrated in five different PAGE systems [15] | Identical migration pattern [15] | Indicates identical size and charge |

| Isoelectric Focusing | Matching isoelectric point [15] | Matching isoelectric point [15] | Confirms identical charge properties |

| Amino Acid Analysis | Excellent agreement in composition [15] | Excellent agreement in composition [15] | Confirms identical primary structure |

| Functional Activity | Activated ATP-dependent proteolysis [15] | Same specific activity as APF-1 [15] | Confirms functional identity |

| Conjugate Formation | Formed identical covalent conjugates [15] | Formed identical covalent conjugates [15] | Confirms identical mechanism of action |

This convergence of data unequivocally established that the heat-stable APF-1 was ubiquitin, a highly conserved, universally expressed protein whose function was previously enigmatic.

The APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation Pathway

Subsequent research, primarily by the Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose teams, delineated the minimal enzymatic cascade required for the conjugation of APF-1/ubiquitin to substrate proteins. This pathway involves three distinct enzyme classes that act in sequence.

The Enzymatic Cascade

The conjugation of ubiquitin to substrate proteins proceeds through a three-step enzymatic cascade [3] [16]:

- Activation (E1): Ubiquitin is activated in an ATP-dependent reaction by E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme). The process involves the formation of a ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate, followed by the transfer of ubiquitin to an active-site cysteine residue on the E1, forming a high-energy thioester bond [17] [16]. This step was characterized by an APF-1-dependent ATP-PPi exchange reaction [17].

- Conjugation (E2): The activated ubiquitin is transferred from E1 to an active-site cysteine of an E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme) via a trans-thioesterification reaction [13] [16].

- Ligation (E3): An E3 (ubiquitin ligase) catalyzes the final transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine ε-amino group on the target protein, forming a stable isopeptide bond [13] [3]. E3s confer substrate specificity to the system.

The following diagram illustrates this core pathway and the formation of a polyubiquitin chain, which serves as the degradation signal.

Figure 1: The APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation and Proteolysis Pathway. The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade activates and conjugates ubiquitin to a substrate protein. A polyubiquitin chain linked through lysine 48 (K48) of ubiquitin targets the substrate for degradation by the 26S proteasome.

Key Experimental Protocols

The foundational understanding of the APF-1/ubiquitin system was derived from several key experimental approaches.

Table 2: Key Experimental Methodologies in Early APF-1 Research

| Experimental Goal | Protocol Description | Key Insight Gained |

|---|---|---|

| Fractionation of the Proteolytic System | ATP-depleted rabbit reticulocyte lysate was fractionated by chromatography (e.g., DEAE-cellulose) into Fraction I (APF-1) and Fraction II (APF-2) [1]. | The system could be biochemically dissected and reconstituted, revealing multiple essential components [1]. |

| Detection of Covalent Conjugates | ¹²⁵I-APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II and ATP. Conjugates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography [1] [14]. | APF-1 formed covalent, ATP-dependent attachments to multiple high molecular weight proteins, suggesting a novel tagging mechanism [14]. |

| Identification of APF-1 as Ubiquitin | APF-1 and authentic ubiquitin were compared via co-migration on multiple gel systems, amino acid analysis, and functional reconstitution assays [15]. | APF-1 and ubiquitin were physically and functionally identical, connecting a new proteolytic pathway to a known protein [15]. |

| Characterization of the Activation Step | E1 enzyme was incubated with ATP, ³²P-PPi, and APF-1/Ub to measure ATP-PPi exchange. Alternatively, formation of a E1-¹²⁵I-APF-1 thioester was assessed [17]. | Activation proceeded through an acyl-adenylate intermediate, with ubiquitin subsequently linked to E1 via a thioester bond [17]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table outlines essential reagents and their functions as used in the seminal APF-1/ubiquitin experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system rich in the components of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, lacking lysosomes, ideal for biochemical fractionation [1] [13]. |

| ATP (and ATP-regenerating System) | The essential energy source for the activation of ubiquitin by E1; required for both conjugation and subsequent proteolysis [1] [14]. |

| Heat-Stable Protein Fraction (APF-1) | The initial designation for the ubiquitin polypeptide; the central modifier that is conjugated to substrate proteins [1]. |

| DEAE-Cellulose & Other Chromatography Media | Used for the fractionation of the reticulocyte lysate into distinct biochemical activities (e.g., Fraction I and II) [1]. |

| ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1/Ubiquitin | Radioactive tracer enabling sensitive detection and analysis of covalent conjugate formation via SDS-PAGE and autoradiography [1] [14]. |

| Model Protein Substrates (e.g., Lysozyme) | Well-characterized proteins used to study the specificity and stoichiometry of APF-1 conjugation in a defined system [14]. |

The meticulous characterization of APF-1 and its capacity to form covalent substrate conjugates unveiled the ubiquitin-proteasome system, a paradigm-shifting discovery in cell biology. The realization that APF-1 was the well-conserved protein ubiquitin immediately suggested the broad physiological relevance of this pathway. The subsequent decades of research have confirmed that this system governs the controlled degradation of countless regulatory proteins, impacting nearly every cellular process, including the cell cycle, DNA repair, transcription, and immune responses [13] [3]. The initial biochemical reconstitution of APF-1 conjugation laid the essential groundwork for understanding a regulatory mechanism as central to cellular homeostasis as phosphorylation, and for the modern development of therapeutic agents that target the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

The discovery that ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) was identical to the previously characterized but functionally enigmatic protein ubiquitin represented a pivotal moment in cell biology. This breakthrough, achieved in 1980, connected a discrete biochemical activity—ATP-dependent protein degradation—with a universal cellular protein of unknown function. The identification hinged on critical experimental data demonstrating that APF-1 and ubiquitin were the same molecular entity, thereby unlocking the proteolytic function of the ubiquitin system. This guide provides a detailed technical analysis of the experimental methodologies and key findings that led to this fundamental discovery, which now underpins modern understanding of regulated protein degradation and its therapeutic applications in disease.

In the late 1970s, two separate lines of biological investigation converged unexpectedly onto the same protein. One track, pursued by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose, focused on elucidating the mechanism of energy-dependent intracellular proteolysis. Their work identified a heat-stable, essential factor they termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1), which formed covalent conjugates with protein substrates in an ATP-requiring reaction [1] [3].

Parallel research in other laboratories had identified a small, highly conserved protein present in all eukaryotic cells. This protein, initially discovered by Gideon Goldstein and colleagues during their search for thymopoietin and later found conjugated to histone H2A in chromatin, was named ubiquitin for its ubiquitous occurrence [1] [13]. However, its physiological function remained mysterious prior to 1980.

Table: Key Proteins Before the Identification Breakthrough

| Protein Designation | Known Properties Pre-1980 | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| APF-1 | Heat-stable polypeptide; essential for ATP-dependent proteolysis in reticulocyte lysates; formed covalent conjugates with substrate proteins [1] | Biochemistry of protein degradation |

| Ubiquitin | 76-amino acid protein; ubiquitous in eukaryotes; conjugated to histone H2A in chromatin; function unknown [13] | Chromatin structure; lymphocyte differentiation |

The Experimental Breakthrough: Methodology and Findings

Biochemical Characterization of APF-1

The research that led to the identification began with rigorous biochemical fractionation of ATP-dependent proteolytic systems from rabbit reticulocytes. Reticulocyte lysates were chosen as a model system because they are devoid of lysosomes, allowing study of non-lysosomal proteolysis [18]. The experimental workflow involved:

- Fraction Preparation: Lysates were separated into two essential fractions: Fraction I (containing APF-1) and Fraction II (containing higher molecular weight components) [1].

- Conjugation Assays: Incubation of (^{125})I-labeled APF-1 with Fraction II and ATP resulted in the covalent attachment of APF-1 to multiple proteins in the fraction. This conjugation was ATP-dependent and reversible upon ATP removal [1].

- Stability Analysis: The APF-1-protein conjugates demonstrated surprising stability, surviving treatment with sodium hydroxide (NaOH), which indicated a covalent bond distinct from a typical labile ester linkage [1].

These observations suggested APF-1 was not a protease but a covalent tag for proteolysis, a novel biological paradigm at the time.

Critical Connection and Identity Confirmation

The conceptual link was made when researchers noticed the biochemical similarity between APF-1 and the known protein ubiquitin. This was primarily based on the precedent of ubiquitin being covalently conjugated to histone H2A via an isopeptide bond, as described by Goldknopf and Busch [1] [13].

The definitive experimental confirmation was achieved by Keith Wilkinson, Michael Urban, and Arthur Haas in the laboratory of Irwin Rose. They obtained authentic ubiquitin and demonstrated that APF-1 and ubiquitin were identical [1] [13] [19]. The key evidence included:

- Co-migration and Structural Identity: APF-1 co-purified and co-migrated with authentic ubiquitin in biochemical assays.

- Functional Replacement: Purified ubiquitin could functionally substitute for APF-1 in supporting ATP-dependent proteolysis in reconstituted systems [1] [13].

Table: Summary of Key Evidence Establishing APF-1/Ubiquitin Identity

| Experimental Evidence | Methodological Approach | Interpretation and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Conjugation | (^{125})I-APF1 formed ATP-dependent, covalent conjugates with proteins in Fraction II [1] | Revealed APF-1's role as a post-translational modifier, analogous to known ubiquitin-histone conjugation |

| Biochemical Similarity | Noted similarity in size, stability, and conjugation behavior between APF-1 and ubiquitin [1] | Suggested the two proteins might be identical, forming a testable hypothesis |

| Direct Identity Confirmation | Purified ubiquitin replaced APF-1 activity in ATP-dependent proteolysis assays [13] [19] | Provided definitive functional proof that APF-1 was ubiquitin |

The following diagram synthesizes the key experimental workflow and the logical progression that led to the conclusive identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system relied on a specific set of biochemical tools and model systems. The table below catalogs key reagents essential for replicating the foundational experiments in this field.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin System Discovery

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Role in Discovery |

|---|---|

| Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system devoid of lysosomes, essential for biochemical fractionation and identification of the non-lysosomal, ATP-dependent proteolytic pathway [1] [18] |

| ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) | Critical energy source required for both the activation of ubiquitin and the proteolytic process itself; its requirement was a key starting point for the research [1] [20] |

| Fraction I (APF-1/Ubiquitin) | The heat-stable fraction from reticulocytes containing free APF-1/Ubiquitin; essential for reconstituting proteolysis in vitro [1] |

| Fraction II (Enzymes & Proteasome) | The high molecular weight fraction containing E1, E2, E3 enzymes and the 26S proteasome; required for conjugation and degradation of ubiquitin-tagged substrates [1] [21] |

| (^{125})I-Labeled APF-1/Ubiquitin | Radiolabeled tracer enabling researchers to monitor the covalent conjugation of APF-1 to protein substrates in Fraction II via autoradiography [1] |

| Authentic Ubiquitin Sample | Purified ubiquitin protein, shared between laboratories, which was used for direct comparison and functional replacement studies to confirm APF-1's identity [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Demonstrating Covalent APF-1 Conjugation

This foundational protocol is adapted from the 1980 work of Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose [1].

- Preparation of Fractions: Lysate rabbit reticulocytes and separate into Fraction I (containing APF-1) and Fraction II (containing higher molecular weight factors) using ion-exchange chromatography.

- Iodination: Purify APF-1 from Fraction I and label with (^{125})I.

- Conjugation Reaction:

- Assay Tube: Combine (^{125})I-APF-1, Fraction II, and 2 mM ATP in an appropriate buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, with Mg(^{2+})).

- Control Tube: Set up an identical reaction omitting ATP or adding a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog.

- Incubation: Incubate mixtures at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Analyze proteins by SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

- Detection: Visualize conjugated proteins by autoradiography of the dried gel. The ATP-dependent appearance of high-molecular-weight, radiolabeled bands indicates successful covalent conjugation of APF-1.

Protocol 2: Functional Replacement Assay for Identity Confirmation

This protocol, based on the work of Wilkinson et al. (1980), confirms the identity of APF-1 as ubiquitin [1] [13].

- Base System Setup: Use a reconstituted proteolysis system where a Fraction II preparation is supplemented with an ATP-regenerating system and a model substrate (e.g., denatured lysozyme).

- Fraction I Depletion: Use a Fraction II preparation that has been rigorously depleted of endogenous APF-1/ubiquitin.

- Experimental Reactions:

- Test Tube 1: Add purified APF-1 isolated via the standard protocol.

- Test Tube 2: Add an equivalent molar amount of authentic, purified ubiquitin.

- Control Tube: No addition of APF-1 or ubiquitin.

- Proteolysis Measurement: Incubate at 37°C and measure substrate degradation over time by methods such as trichloroacetic acid (TCA) solubility of residual substrate or release of radioactive peptides from a labeled substrate.

- Interpretation: The functional replacement of APF-1 activity by purified ubiquitin, resulting in the restoration of ATP-dependent proteolysis, provides definitive evidence that APF-1 and ubiquitin are the same protein.

The critical breakthrough of identifying APF-1 as ubiquitin transformed a discrete biochemical observation into a fundamental biological principle. It provided a functional identity for ubiquitin and revealed that the molecule served as a universal tag for targeted protein destruction [18]. This discovery was the cornerstone that allowed subsequent research, including the genetic and cell biological work from Alexander Varshavsky's group, to elucidate the vast physiological roles of the ubiquitin system in regulating the cell cycle, DNA repair, transcription, and stress responses [22] [13] [19].

From a therapeutic perspective, establishing the identity of APF-1 opened the door to understanding the molecular basis of numerous diseases, including many cancers and neurodegenerative disorders, which are now known to involve dysregulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [19] [18]. This foundational knowledge directly enabled the development of targeted therapies, such as proteasome inhibitors, validating the immense practical significance of this basic biochemical discovery.

The discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system stands as a paradigmatic example of how international collaboration between biochemists with complementary expertise can unravel fundamental biological processes. This whitepaper traces the seminal partnership between Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose, whose combined intellectual curiosity and methodological rigor elucidated the ATP-dependent ubiquitin tagging mechanism for protein degradation. Their work, initiated through a chance meeting at a Fogarty Foundation conference in 1977 and sustained through decade-long transatlantic collaboration, transformed our understanding of cellular regulation and established a new paradigm in post-translational modification. This technical analysis examines the experimental methodologies, key reagents, and conceptual breakthroughs that defined their collaboration, providing insights into the biochemical foundation of what would become the 2004 Nobel Prize-winning discovery of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis.

Prior to the groundbreaking work on ubiquitin, the field of intracellular protein degradation was characterized by a fundamental paradox: the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is thermodynamically exergonic, yet experimental evidence consistently demonstrated that proteolysis in mammalian cells required metabolic energy [1]. This apparent contradiction was first documented by Melvin Simpson in 1953 through isotopic labeling studies, yet the mechanism remained obscure for the subsequent 25 years [1] [23]. By the late 1970s, researchers had established that damaged or abnormal proteins were rapidly cleared from cells and that enzymes catalyzing rate-limiting steps in metabolic pathways were generally short-lived, suggesting sophisticated regulation rather than random degradation [1].

The scientific landscape was dominated by the lysosomal hypothesis of protein degradation, despite accumulating evidence that this organelle could not account for the observed specificity and ATP dependence [2]. The convergence of three distinct investigative trajectories—Hershko's work on ATP-dependent proteolysis, Ciechanover's biochemical fractionation expertise, and Rose's mechanistic enzymology background—would ultimately provide the necessary intellectual and technical framework to resolve this decades-old mystery.

The Collaborative Network: Intellectual Synergies

Investigator Backgrounds and Complementary Expertise

The collaboration brought together scientists with distinct yet complementary expertise, creating a synergistic environment for discovery:

Avram Hershko (Technion-Israel Institute of Technology): Having completed both MD (1965) and PhD (1969) degrees at Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School, Hershko developed an interest in protein degradation during postdoctoral work with Gordon Tompkins at UCSF. His early studies focused on tyrosine amino transferase and bulk protein turnover, establishing the experimental foundation for investigating ATP-dependent proteolysis [1].

Aaron Ciechanover (Technion-Israel Institute of Technology): After completing military service following his MD (1974), Ciechanover joined Hershko's laboratory as a graduate student, where he would complete his PhD (1981) while developing the critical fractionation approaches that enabled system dissection [1].

Irwin A. "Ernie" Rose (Fox Chase Cancer Center): As a mechanistic enzymologist with a PhD (1952) from the University of Chicago, Rose brought expertise in isotopic labeling and enzyme reaction mechanisms. His interest in protein degradation dated to conversations with Simpson at Yale about the ATP dependence of proteolysis [1].

Formation and Structure of the Collaboration

The partnership began formally in 1977 after Hershko and Rose met at a Fogarty Foundation meeting where they discovered their mutual interest in ATP-dependent proteolysis [1]. Rose subsequently invited Hershko to conduct a sabbatical in his laboratory at the Institute for Cancer Research in Philadelphia, initiating a decade-long collaboration that featured annual summer visits by the Israeli researchers [1]. This arrangement provided access to specialized resources and additional expertise, including postdoctoral fellows Art Haas, Keith Wilkinson, and Cecile Pickart, who would make crucial contributions to identifying the molecular components [23].

Table: Key Investigators and Their Contributions

| Investigator | Institutional Affiliation | Primary Expertise | Key Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avram Hershko | Technion-Israel Institute of Technology | ATP-dependent proteolysis | System conception; experimental design |

| Aaron Ciechanover | Technion-Israel Institute of Technology | Biochemical fractionation | Fractionation methodology; conjugation studies |

| Irwin Rose | Fox Chase Cancer Center | Mechanistic enzymology | Isotopic methods; mechanistic interpretation |

| Art Haas | Fox Chase Cancer Center | Ubiquitin biochemistry | Covalent conjugation characterization |

| Keith Wilkinson | Fox Chase Cancer Center | Protein identification | APF-1/ubiquitin identity confirmation |

Experimental Breakthroughs: Methodological Innovation

System Development and Fractionation Strategy

The critical experimental foundation was established through adaptation of the reticulocyte lysate system, which Etlinger and Goldberg had previously demonstrated exhibited ATP-dependent proteolysis of denatured proteins while lacking lysosomes [1] [23]. This system provided a biochemical platform amenable to fractionation, avoiding the complications of lysosomal proteases.

The key methodological breakthrough came when Hershko and Ciechanover successfully separated the reticulocyte lysate into two essential complementing fractions [1] [2]:

- Fraction I: Contained a small, heat-stable protein designated APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1)

- Fraction II: Contained a high molecular weight component (initially termed APF-2) later identified as the proteasome

This fractionation approach enabled detailed characterization of the individual components and reconstruction of the ATP-dependent proteolytic activity, establishing the multi-component nature of the system [24] [2].

Discovery of Covalent Protein Tagging

The seminal observation that transformed understanding of the system came from experiments examining the association between APF-1 and fraction II components. Researchers observed that ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 was promoted to a high molecular weight form upon incubation with fraction II and ATP [1]. Surprisingly, this association:

- Required low concentrations of ATP

- Was reversed upon ATP removal

- Remained stable under high pH conditions

- Survived NaOH treatment, indicating a covalent linkage

Further investigation revealed that APF-1 was covalently bound to multiple proteins in fraction II as judged by SDS/PAGE, with the bond later identified as an isopeptide linkage between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and ε-amino groups of lysine residues on target proteins [1] [16].

Table: Key Experimental Findings from Covalent Conjugation Studies

| Experimental Observation | Technical Approach | Interpretation | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP-dependent shift to HMW forms | ¹²⁵I-APF-1 incubation with Fraction II | Covalent modification | First evidence of protein tagging |

| Stability at high pH | NaOH treatment | Non-labile bond | Distinguished from electrostatic interactions |

| Multiple protein targets | SDS/PAGE analysis | Broad substrate range | Suggested general regulatory mechanism |

| Similar nucleotide requirements | Comparative kinetics | Functional linkage | Connected conjugation to proteolysis |

| Reversibility | ATP depletion | Dynamic regulation | Suggested regulatory control points |

Identification of APF-1 as Ubiquitin

The critical connection between APF-1 and the previously characterized protein ubiquitin emerged through interdisciplinary communication. A conversation between postdoctoral fellows Art Haas and Michael Urban revealed the similarity between APF-1 behavior and the known covalent modification of histone H2A by ubiquitin [1]. This insight led to comparative studies confirming the identity of APF-1 as ubiquitin, previously discovered by Gideon Goldstein in 1975 and known to be conjugated to histones, though for reasons unrelated to degradation [1] [16].

This connection unified two previously separate research areas—chromatin biology and protein degradation—and provided immediate access to structural information about ubiquitin that accelerated mechanistic studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The experimental breakthroughs depended on carefully selected and characterized research reagents that enabled precise dissection of the ubiquitin system:

Table: Essential Research Reagents in Early Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Composition/Characteristics | Experimental Function | Key Insights Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | Lysate from immature red blood cells | ATP-dependent proteolysis assay system | Provided lysosome-free system for fractionation |

| APF-1 (Ubiquitin) | 8.6 kDa heat-stable protein | Covalent modification component | Identification of tagging mechanism |

| Fraction I | APF-1 containing fraction | Reconstitution of proteolytic activity | Established requirement for soluble factor |

| Fraction II | High molecular weight components | Reconstitution of proteolytic activity | Contained E2, E3, and proteasome activities |

| ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 | Radioiodinated ubiquitin | Tracing conjugation fate | Demonstrated covalent attachment to substrates |

| ATP-regenerating System | ATP, creatine phosphate, creatine kinase | Maintained energy dependence | Sustained ubiquitination cascade |

Biochemical Mechanisms: The Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

The collaboration systematically elucidated the enzymatic cascade responsible for ubiquitin conjugation, defining three essential enzyme classes:

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme

The initial step involves ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin through formation of a ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate, followed by transfer to a active site cysteine residue on E1, forming a thioester linkage [23] [16]. Haas employed isotope exchange at equilibrium to establish the reaction sequence and kinetic parameters, demonstrating tight binding constants (K~m~ for ATP ≈40 μM; K~m~ for ubiquitin = 0.58 μM) that ensure the system remains activated under physiological conditions [23].

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes

The activated ubiquitin is transferred to a cysteine residue on E2 enzymes (ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes) through trans-thioesterification [24] [16]. The human genome encodes approximately 35 E2 enzymes characterized by a conserved ubiquitin-conjugating catalytic (UBC) fold [16].

E3: Ubiquitin Ligases

E3 enzymes catalyze the final transfer of ubiquitin to substrate proteins, typically forming an isopeptide bond with lysine ε-amino groups [24] [16]. Two major E3 families were identified:

- HECT domain E3s: Form transient thioester intermediates with ubiquitin

- RING domain E3s: Facilitate direct transfer from E2 to substrate

The collaboration established that E3 enzymes provide substrate specificity, explaining how the system selectively targets particular proteins under specific physiological conditions [13].

Diagram: Ubiquitin Proteasome Pathway Cascade. The three-enzyme cascade (E1-E2-E3) mediates ubiquitin activation, conjugation, and ligation to substrate proteins, leading to polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation.

Visualization of Experimental Workflow

The critical experimental approaches that led to the discovery of the ubiquitin system are summarized in the following workflow:

Diagram: Key Experimental Workflow in Ubiquitin Discovery. The critical path from system establishment through fractionation to mechanistic elucidation.

Contemporary Relevance and Therapeutic Applications

The foundational work on ubiquitin has proven exceptionally influential across biomedical research and therapeutic development. The ubiquitin-proteasome system is now recognized as a master regulator of virtually all eukaryotic cellular processes, including cell cycle control, DNA repair, transcription, immune response, and apoptosis [25]. Dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling is implicated in numerous disease pathologies, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions [25].

The mechanistic understanding of ubiquitin conjugation has enabled emerging therapeutic strategies, most notably:

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Bortezomib and other agents that directly target the proteasome for cancer therapy

- Targeted Protein Degradation: PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) and molecular glues that harness the ubiquitin system to selectively degrade disease-causing proteins [26]

- E3 Ligase Modulation: Small molecules targeting specific E3 ligases to manipulate substrate degradation

These applications demonstrate how the fundamental biochemical insights from the Hershko-Ciechanover-Rose collaboration continue to drive innovative therapeutic approaches decades later.

The collaboration between Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose exemplifies how convergent expertise, methodological rigor, and intellectual curiosity can unravel biological complexity. Their systematic dissection of the ubiquitin system transformed protein degradation from a neglected backwater of biochemistry to a central paradigm in cellular regulation. The partnership combined Hershko's biological insight, Ciechanover's experimental skill, and Rose's mechanistic rigor to overcome technical challenges and conceptual barriers. Their work established not only a new biochemical pathway but also a conceptual framework for understanding how covalent protein modification directs functional outcomes—a framework that continues to expand with the discovery of new ubiquitin-like modifiers and their specialized functions. This collaboration underscores the enduring power of international scientific partnership in advancing fundamental knowledge with profound basic and translational implications.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade: From Biochemical Reconstitution to Modern Applications

The discovery of the three-step enzymatic cascade has its roots in the pioneering research on a heat-stable protein initially designated APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1). This early work, which laid the foundation for our current understanding of the ubiquitin system, revealed a critical ATP-dependent proteolytic mechanism in reticulocyte extracts [25]. APF-1 was later identified as ubiquitin, a 76-amino-acid protein highly conserved across eukaryotes [27] [25]. The subsequent elucidation of its covalent attachment to substrate proteins earmarked for degradation revolutionized our understanding of regulated intracellular proteolysis [25]. This seminal discovery unveiled a complex post-translational modification system that extends far beyond protein degradation, regulating virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology [25].

The ubiquitination process is orchestrated by a sequential E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascade [28] [29] [25]. This pathway involves the coordinated action of ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), which together confer specificity and precision to the modification of thousands of cellular proteins [25]. The human genome encodes a remarkable diversity of these enzymes, with approximately 2 E1s, around 50 E2s, and over 600 E3s, allowing for tremendous substrate specificity and functional diversity [29] [30]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of this core enzymatic cascade, framing it within its historical context and highlighting its critical importance in cellular regulation and therapeutic development.

The Core Enzymatic Machinery

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme

The ubiquitination cascade initiates with the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, which serves as the entry point for ubiquitin into the pathway. Humans primarily possess one major E1 enzyme (UAE or UBA1) for ubiquitin activation, though UBA6 can also activate ubiquitin [29]. The E1 enzyme performs the ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin through a two-step mechanism:

- Step 1: E1 consumes ATP to form a high-energy ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate.

- Step 2: The activated ubiquitin is transferred to a catalytic cysteine residue within the E1 active site, forming a high-energy thioester bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and the E1 cysteine sulfhydryl group [29] [31].

This activation reaction is fundamental to the entire ubiquitination process, as it primes ubiquitin for subsequent transfer through the cascade. The E1 enzyme interacts with all downstream E2 enzymes, serving as a common gateway for ubiquitin activation [30].

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme

The activated ubiquitin is subsequently transferred from E1 to a E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme via a transthiolation reaction [29] [31]. This transfer results in the formation of a similar thioester bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and a conserved cysteine residue within the E2 active site [30].

The human genome encodes approximately 50 E2 enzymes, which demonstrate varying degrees of specificity for different E1 and E3 partners [29] [32]. While E2s alone lack the ability to recognize specific protein substrates, they play a crucial role in determining the type of ubiquitin chain linkage formed on the substrate, particularly in conjunction with RING-type E3 ligases [29] [30]. The E2 serves as a critical intermediary in the cascade, receiving activated ubiquitin and collaborating with E3 ligases to achieve substrate-specific modification.

E3: Ubiquitin Ligase

The final and most diverse component of the cascade is the E3 ubiquitin ligase, which is primarily responsible for substrate recognition specificity [31] [30]. With over 600 members in the human genome, E3 ligases impart remarkable specificity to the ubiquitination system, with each E3 typically recognizing a discrete set of substrate proteins [30]. E3 ligases function by simultaneously binding to both the E2~ubiquitin thioester conjugate and the protein substrate, facilitating the transfer of ubiquitin to the substrate [30].

E3 ligases are classified into several major families based on their structural features and mechanisms of action:

Table 1: Major Families of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

| E3 Family | Mechanism of Action | Representative Examples | Catalytic Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| RING | Acts as a scaffold, facilitating direct ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate | APC/C, SCF complex [30] | Non-catalytic [31] |

| HECT | Forms a catalytic thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before substrate transfer | E6-AP [28] [30] | Catalytic [31] |

| U-box | Similar to RING but with a different structural domain | UFD2 [30] | Non-catalytic [31] |

| PHD-finger | Rare family with specialized domain structure | - | Varies |

The fundamental difference in mechanism between RING and HECT E3s was elegantly demonstrated in the seminal 1995 study of E6-AP, which showed that formation of a ubiquitin thioester on the E3 itself is an essential intermediate step for HECT-type E3s, whereas RING-type E3s facilitate direct transfer from E2 to substrate [28].

The Ubiquitin Transfer Mechanism

The complete ubiquitin transfer follows an ordered pathway that ensures the faithful modification of specific cellular proteins. The cascade proceeds through these defined steps:

- E1 Activation: UAE (E1) consumes ATP to form a thioester bond with ubiquitin [29] [31].

- E2 Conjugation: Ubiquitin is transferred from E1 to an E2 conjugating enzyme via transthiolation, preserving the high-energy thioester bond [29] [31] [30].

- E3 Ligation: The E3 ligase binds both the E2~ubiquitin complex and the protein substrate, facilitating ubiquitin transfer.

- Isopeptide Bond Formation: The C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin forms an isopeptide bond with the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on the substrate protein [29] [31] [30].

For HECT-domain E3 ligases, an additional step occurs: ubiquitin is first transferred from the E2 to a catalytic cysteine within the HECT domain, forming a third thioester intermediate, before final transfer to the substrate [28] [30]. This distinctive mechanism was crucial in establishing that E3s possess defined enzymatic activity rather than functioning merely as docking proteins [28].

The following diagram illustrates the complete ubiquitin transfer cascade, highlighting the key intermediates and energy requirements:

Diversity of Ubiquitin Signals

A remarkable feature of the ubiquitin system is its ability to generate diverse signals through different ubiquitin modifications. Ubiquitin itself contains seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can serve as attachment points for additional ubiquitin molecules, enabling the formation of various polyubiquitin chains [25]. These different linkage types constitute a complex "ubiquitin code" that is interpreted by specialized receptor proteins to determine the functional outcome for the modified substrate [25].

Table 2: Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Functional Consequences

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Structural Features | Cellular Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Targets proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome [29] [33] | Compact structure resistant to many DUBs [33] | Protein turnover, homeostasis [29] |

| K63-linked | Non-degradative signaling [29] | More open, extended chain structure [29] | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis [29] |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation [29] | - | Cell cycle regulation [29] |

| M1-linked (Linear) | Inflammatory signaling [25] | - | NF-κB activation, immune response [25] |

| Monoubiquitination | Non-degradative signaling [30] | Single ubiquitin moiety | Endocytosis, histone regulation [30] |

The functional diversity of ubiquitin modifications extends the regulatory potential of the system far beyond protein degradation. For instance, monoubiquitination typically serves as a signal in membrane protein trafficking and histone regulation, while K63-linked chains are important for DNA repair, endocytosis, and activation of signaling pathways such as NF-κB [29] [30]. The specific interpretation of these different ubiquitin signals is essential for appropriate cellular responses.

Experimental Analysis of the Cascade

Key Experimental Evidence

The fundamental mechanisms of the E1-E2-E3 cascade were established through rigorous biochemical experimentation. A landmark study published in Nature in 1995 provided crucial evidence for the thioester cascade mechanism [28]. This research demonstrated that for the HECT E3 ligase E6-AP (involved in human papillomavirus E6-induced ubiquitination of p53), formation of a ubiquitin thioester on the E3 itself is an essential intermediate step [28]. The experimental approach involved:

- Thioester Assay: Detection of covalent E3-ubiquitin intermediates under non-reducing conditions.

- Cysteine Mapping: Identification of the specific cysteine residue (Cys-357) within a highly conserved region of E6-AP required for thioester formation [28].

- Transfer Order Analysis: Establishing the order of ubiquitin transfer as E1→E2→E6-AP→substrate through timed reactions and intermediate trapping [28].

This work was pivotal in transforming the understanding of E3 ligases from mere docking proteins to enzymes with defined catalytic activities [28].

Contemporary Research Methods

Modern research employs sophisticated techniques to study ubiquitination mechanisms:

- Orthogonal Ubiquitin Transfer (OUT): Engineered E1-E2-E3-ubiquitin pairs that operate orthogonally to native systems enable specific mapping of E3 substrates and signaling networks [32].

- Deubiquitinase (DUB) Profiling: Studying the resistance of different ubiquitin chain types to specific DUBs (e.g., Lys48-linked chains are resistant to USP7) provides insights into chain stability and function [33].

- Computational Prediction: Deep learning approaches like 2DCNN-UPP use dipeptide deviation features (DDE) and convolutional neural networks to identify ubiquitin-proteasome pathway proteins from sequence data [27].

- Mass Spectrometry: Quantitative proteomics methods enable comprehensive mapping of ubiquitination sites and chain linkage types across the proteome [25].

The following diagram illustrates a representative experimental workflow for analyzing ubiquitination mechanisms:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitination

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Inhibitors | PYR-41, TAK-243 | Block ubiquitin activation, used to study global ubiquitination dependence [29] |

| E2 Enzymes | UbcH5, UbcH7, Ubc13 | Specific E2 conjugating enzymes for in vitro reconstitution studies [29] [32] |

| E3 Ligase Inhibitors | Nutlins (MDM2), SM-406 (IAP), Clomipramine (Itch) | Target specific E3-substrate interactions for functional studies [31] |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 (pan-DUB inhibitor) | Study effects of blocked deubiquitination [29] |

| Engineered Enzyme Pairs | xUB-xE1-xE2 orthogonal systems | Isolate specific ubiquitination pathways without cross-reactivity [32] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage, K63-linkage specific antibodies | Detect specific polyubiquitin chain types [25] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-vinylsulfone, HA-Ub-VS | Label active site cysteines in E2s, E3s, and DUBs [29] |

Therapeutic Targeting and Clinical Relevance

The ubiquitin-proteasome system has emerged as a promising therapeutic target, particularly in oncology. The clinical validation of this approach came with the approval of bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma [29]. This success prompted extensive drug discovery efforts targeting various components of the ubiquitin cascade.

Targeting E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

E3 ligases represent particularly attractive drug targets due to their substrate specificity. Unlike broader inhibitors that affect global ubiquitination, E3-targeted therapies offer the potential for precise intervention in specific pathological pathways [31]. Several strategies have been employed to develop E3 ligase inhibitors:

- Direct Catalytic Inhibition: Small molecules that block the enzymatic activity of HECT-domain E3s [31].

- Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibitors: Compounds that disrupt the interaction between RING-type E3s and their cognate E2 enzymes [31].

- Substrate Recognition Blockers: Molecules that interfere with E3-substrate binding [31].

Notable examples include Nutlins, which inhibit the MDM2-p53 interaction, leading to p53 stabilization and activation of apoptosis in cancer cells [31]. Similarly, IAP (Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein) antagonists such as SM-406 and GDC-0152 promote cell death in tumors [31].

Enzyme Cascades in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Beyond direct therapeutic targeting, the E1-E2-E3 cascade principle has inspired the development of multi-enzymatic cascades for sustainable pharmaceutical synthesis [34]. These approaches leverage the efficiency and specificity of enzymatic reactions to produce complex molecules:

- Molnupiravir Synthesis: A six-enzyme cascade (with two engineered enzymes) developed by Merck & Co. achieves a 69% yield of this COVID-19 therapeutic, significantly outperforming the traditional 10-step chemical synthesis [34].

- Islatravir Production: A nine-enzyme cascade (with five engineered enzymes) enables the synthesis of this HIV investigational drug with 51% yield, avoiding the need for protecting groups and multiple isolation steps required in conventional chemical synthesis [34].

These industrial applications demonstrate how engineered enzyme cascades can provide shorter, more efficient, and environmentally friendly synthetic routes to complex pharmaceutical compounds [34].

The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism that extends far beyond its initial discovery in the context of the heat-stable protein APF-1 and ATP-dependent protein degradation. This sophisticated system exemplifies how a conceptually simple biochemical modification—the covalent attachment of ubiquitin—can achieve remarkable specificity and functional diversity through a multi-enzyme cascade and complex "ubiquitin code."

The continued elucidation of ubiquitin cascade mechanisms, combined with advanced technologies for studying and engineering these pathways, promises to unlock new therapeutic opportunities across a spectrum of human diseases. From the development of targeted protein degradation therapies to sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing, our growing understanding of this essential cellular pathway continues to drive innovation in both basic research and clinical applications.

Polyubiquitin Chains as the Proteasomal Degradation Signal

The discovery that polyubiquitin chains serve as the primary degradation signal for the proteasome is inextricably linked to the pioneering investigation of a heat-stable protein known as ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1). In the late 1970s and early 1980s, groundbreaking work using a biochemical fractionation approach in rabbit reticulocytes revealed that APF-1 was an essential component of a non-lysosomal, ATP-dependent proteolytic system [15] [1]. The critical breakthrough came when APF-1 was identified as the previously known but functionally enigmatic protein, ubiquitin [15] [1]. This discovery unveiled a novel biological paradigm: a post-translational modification where the covalent attachment of multiple ubiquitin molecules to a substrate protein signals its destruction [1] [2].

Subsequent research established that this signal is not merely multiple monoubiquitination, but a distinct polyubiquitin chain in which the C-terminus of one ubiquitin molecule is covalently linked to a specific lysine residue on the preceding ubiquitin [35] [16]. The type of linkage within these chains creates a complex "ubiquitin code" that determines the fate of the modified protein [25]. Among the eight possible homotypic polyubiquitin chains (linked via Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, Lys63, or the N-terminal methionine Met1), the Lys48 (K48)-linked chain was the first identified and remains the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [35] [16]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical overview of the structure, recognition, and experimental analysis of polyubiquitin chains as proteasomal degradation signals, contextualized within the historical framework of APF-1 research.

The Biochemical Basis of Polyubiquitin Chain Signaling

The Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

The process of polyubiquitin chain formation is a sequential enzymatic cascade involving three key enzymes [4] [16]:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): In an ATP-dependent process, E1 forms a high-energy thioester bond with the C-terminal glycine (Gly76) of ubiquitin.

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): The activated ubiquitin is transferred from E1 to a catalytic cysteine residue on an E2 enzyme, forming another thioester intermediate.

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): An E3 enzyme, which confers substrate specificity, catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to an ε-amino group of a lysine residue on the target protein, forming an isopeptide bond. To form a chain, this process repeats by attaching additional ubiquitin molecules to a lysine residue (most commonly K48) on the previously conjugated ubiquitin moiety [16].

This cascade results in a polyubiquitin chain that functions as a binding scaffold for proteasomal receptors [35].

Linkage Type Determines Functional Outcome

The specificity of the polyubiquitin signal is largely determined by the lysine residue within ubiquitin used for chain elongation. Different linkages are recognized as distinct cellular signals that direct proteins to diverse fates [35] [25]. The following table summarizes the primary functions of the major ubiquitin chain linkages.

Table 1: Functional Specificity of Major Polyubiquitin Linkages

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Structural Role | Proteasomal Degradation |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Canonical proteasomal degradation signal [35] [16] | Compact structure [35] | Primary signal [35] |

| K11 | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation (ERAD) [35] | Compact structure [35] | Yes [35] |

| K29 | Proteasomal degradation [35] | Not specified in sources | Yes [35] |

| K63 | DNA repair, endocytosis, NF-κB signaling, inflammation [35] [25] | Open, extended structure [35] | Generally No (non-proteolytic) [35] |

| M1 (Linear) | NF-κB activation, inflammatory signaling [25] | Linear structure [25] | No (non-proteolytic) [25] |

While K48-linked chains are the predominant degradation signal, it is now established that other chain types, notably K11 and K29, can also target substrates for proteasomal degradation, highlighting the complexity and versatility of the ubiquitin code [35].

Recognition by the Proteasome: Ubiquitin Receptors and Commitment Steps

The 26S proteasome is a 2.5 MDa multi-subunit complex responsible for the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins [35]. It consists of a cylindrical 20S core particle, where proteolysis occurs, capped by one or two 19S regulatory particles that recognize ubiquitinated substrates, unfold them, and translocate them into the core [35]. The recognition of polyubiquitin chains is a critical, regulated step mediated by dedicated ubiquitin receptors.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Ubiquitin Receptors

The proteasome utilizes a combination of intrinsic subunits and transiently associated adaptor proteins to bind polyubiquitinated substrates [35].

Table 2: Ubiquitin Receptors of the 26S Proteasome

| Receptor | Type | Location | Ubiquitin-Binding Domain | Key Functions & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|