From Discovery to Therapy: The Historical Journey and Modern Impact of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS), tracing its foundational discovery in the 1980s to its current status as a pivotal target in precision medicine.

From Discovery to Therapy: The Historical Journey and Modern Impact of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS), tracing its foundational discovery in the 1980s to its current status as a pivotal target in precision medicine. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details the core enzymatic cascade and historical milestones. The scope extends to modern 'ubiquitinomics' methodologies, the application of UPS-targeting therapies like proteasome inhibitors and PROTACs in oncology, and the troubleshooting of challenges such as drug resistance. Finally, it validates the system's role through comparative analysis in immunology and neurodegeneration, synthesizing key insights for future therapeutic innovation.

The Foundational Discovery and Core Mechanics of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

Prior to the discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), scientific understanding of intracellular protein degradation was predominantly centered on the role of lysosomes. These membrane-bound organelles, with their acidic and protease-filled interiors, were considered the primary site for the breakdown of exogenous proteins, aged organelles, and cellular debris [1]. However, this model could not account for the selective, energy-dependent turnover of specific proteins observed in cells. A pivotal shift began with 1977 work by Joseph Etlinger and Alfred L. Goldberg on ATP-dependent protein degradation in reticulocytes (immature red blood cells), which notably lack lysosomes [1] [2]. This research provided the first compelling evidence for a second, non-lysosomal intracellular degradation mechanism, setting the stage for a paradigm-changing discovery.

The Discovery of a Heat-Stable Polypeptide

Initial Identification and Characterization

In 1978, the laboratory of Avram Hershko at the Technion, with key contributions from Aaron Ciechanover, made the critical observation that would eventually lead to the identification of the ubiquitin system. They described a heat-stable polypeptide that was an essential component of the ATP-dependent proteolytic system in reticulocytes [1] [2] [3]. This polypeptide, with a molecular weight of approximately 8.5 kDa, was found to be indispensable for ATP-dependent proteolysis. The remarkable heat stability of this factor—retaining its biological activity after boiling—became a crucial property that facilitated its isolation and subsequent characterization, distinguishing it from most other cellular proteins.

The initial experiments demonstrated that this polypeptide participated in a novel enzymatic cascade. It was first activated in an ATP-dependent manner to form a high-energy intermediate, later identified as a thiolester linkage with the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [4]. This activated polypeptide could then be conjugated to substrate proteins, marking them for degradation by a downstream proteolytic complex.

From APF-1 to Ubiquitin

The heat-stable factor was initially termed ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1) [1]. A crucial breakthrough came when APF-1 was recognized to be identical to a previously known protein, ubiquitin, which had been identified in 1975 but whose function was unknown [1]. The name "ubiquitin" derived from its ubiquitous presence across virtually all eukaryotic cell types [5]. The connection between the histone-modifying activity of ubiquitin and its role in proteolysis represented a seminal moment of convergence in biochemical research.

Elucidating the Enzymatic Cascade

The discovery of the heat-stable polypeptide prompted a series of experiments to unravel the mechanism by which it targeted proteins for degradation. Key methodological advances enabled researchers to dissect this complex process.

The Covalent Affinity Purification Breakthrough

A pivotal methodological innovation came in 1982 with the development of "covalent affinity" chromatography for purifying the ubiquitin-activating enzyme [4]. This sophisticated approach exploited the covalent nature of the intermediate formed during the activation process.

- Affinity Matrix: Ubiquitin was covalently linked to a Sepharose column.

- Binding Requirements: Enzyme binding required the presence of ATP and Mg²âº, essential cofactors for the activation reaction.

- Elution Characteristics: The bound enzyme could not be displaced by high salt concentrations but was specifically eluted by conditions that disrupt thiolester bonds, including elevated pH, increased thiol compound concentrations, or joint supplementation of AMP and pyrophosphate [4].

This purification strategy confirmed the formation of a covalent, thiolester intermediate between the activating enzyme and the Sepharose-bound ubiquitin. The purified enzyme was characterized as a 210 kDa protein composed of two 105 kDa subunits [4].

The Three-Enzyme Cascade

The combined work of Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose at the Fox Chase Cancer Center elucidated the fundamental three-enzyme cascade that constitutes the ubiquitination pathway [1]:

Table 1: The Ubiquitin Conjugation Enzyme Cascade

| Enzyme | Designation | Number in Humans | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme | 2 | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a thiolester bond |

| E2 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme | ~38 | Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1 and cooperates with E3 for substrate transfer |

| E3 | Ubiquitin ligase | >600 | Recognizes specific substrate proteins and facilitates ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate |

This cascade enables the specific tagging of target proteins with ubiquitin, marking them for recognition and degradation by the proteasome. The extensive diversity of E3 ligases, in particular, provides the substrate specificity that allows the UPS to regulate a vast array of cellular processes with precision [5].

The Proteasome: From Discovery to Molecular Machinery

Identification of the Proteolytic Complex

While the ubiquitination system was being elucidated, parallel research was identifying the proteolytic machinery that would execute the final degradation step. In the late 1970s, a large multi-protein complex with proteolytic activity was identified and given various names, including multicatalytic proteinase complex by Sherwin Wilk and Marion Orlowski [1]. Later, the ATP-dependent complex responsible for ubiquitin-dependent degradation was discovered and named the 26S proteasome [1].

The 26S proteasome is composed of two primary components:

- 20S Core Particle: A barrel-shaped complex of four stacked rings (α7β7β7α7) forming a central proteolytic chamber where protein degradation occurs [1].

- 19S Regulatory Particle: A cap structure that recognizes polyubiquitinated proteins, removes the ubiquitin tags, unfolds the substrate, and translocates it into the 20S core for degradation [1].

Structural Insights

Significant advances in understanding proteasome function came with structural elucidation. The first structure of the proteasome core particle was solved by X-ray crystallography in 1994 [1]. More recently, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies have revealed the architecture of the complete 26S proteasome in complex with polyubiquitinated substrates, providing atomic-level insights into the mechanisms of substrate recognition, deubiquitination, unfolding, and degradation [1].

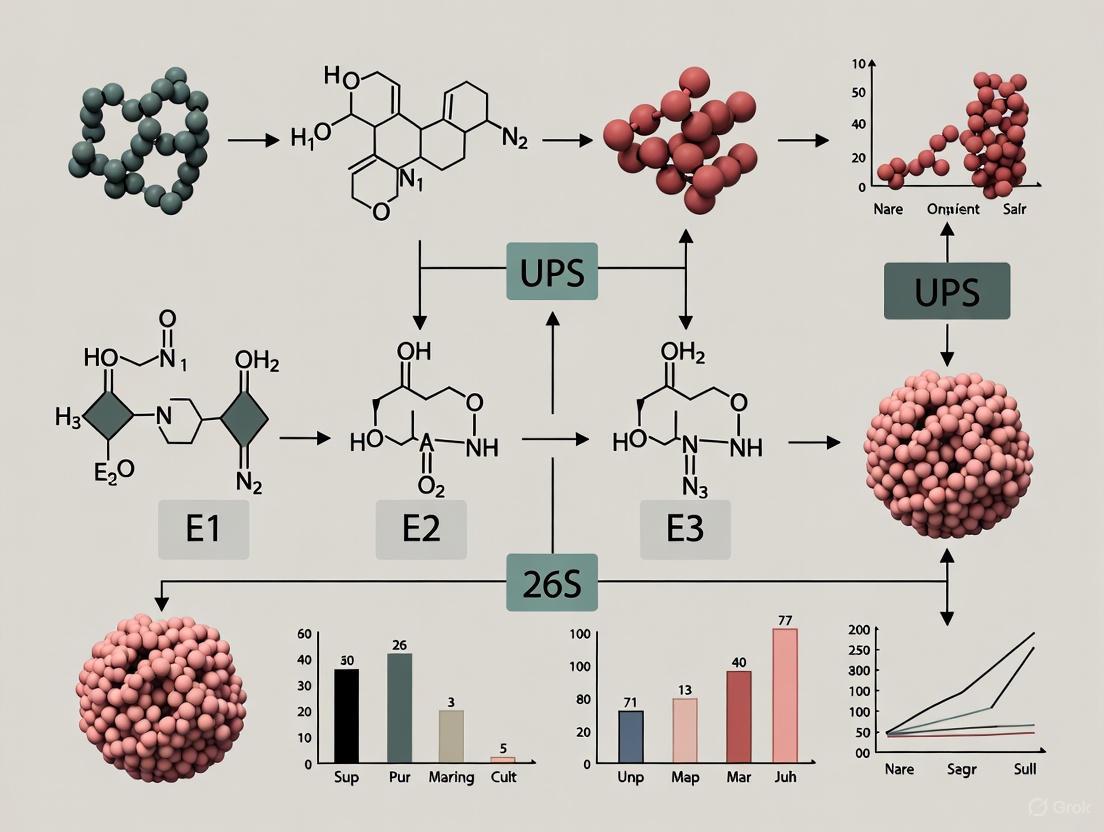

Diagram 1: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Pathway. This diagram illustrates the complete pathway from substrate recognition to degradation, highlighting the key steps of ubiquitination and proteasomal processing.

Methodologies and Research Tools

The elucidation of the UPS relied on the development of sophisticated experimental approaches and research tools that enabled researchers to probe this complex system.

Key Experimental Protocols

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods in UPS Discovery

| Method/Technique | Application in UPS Discovery | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Affinity Chromatography [4] | Purification of E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme using ubiquitin-Sepharose | Confirmed thiolester intermediate formation; enabled enzyme characterization |

| ATP-dependent Proteolysis Assays [1] [2] | Measuring degradation of radiolabeled proteins in reticulocyte extracts | Established energy requirement and identified essential components |

| Heat Inactivation Studies [1] [3] | Differential stability of proteolytic system components | Identified heat-stable factor (APF-1/ubiquitin) as distinct from proteolytic machinery |

| Immunoprecipitation & Western Blotting [5] | Detection of ubiquitin-protein conjugates and chain topology | Revealed diversity of ubiquitin linkages and conjugate structures |

Modern Research Reagents

Contemporary ubiquitin research employs sophisticated tools to dissect the complexity of ubiquitin signaling:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin System Studies

| Research Tool | Composition/Type | Primary Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies [5] | Monoclonal antibodies | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence | Detection of specific polyubiquitin chain types (e.g., K48, K63) |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) [5] | Engineered ubiquitin-binding domains | Ubiquitin conjugate purification, stabilization | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitinated proteins; prevent deubiquitination |

| Activity-Based DUB Probes [5] | Selective DUB inhibitors | Enzyme activity profiling, inhibitor screening | Identification of active deubiquitinating enzymes and their inhibition |

| Di-Gly Antibody (KGG Remnant) [5] | Anti-KGG monoclonal antibody | Ubiquitinomics, mass spectrometry | Enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides after tryptic digest |

| Recombinant E1, E2, E3 Enzymes [6] | Purified recombinant proteins | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Reconstitution of ubiquitination cascades with defined components |

From Fundamental Discovery to Therapeutic Applications

The discovery of the UPS has fundamentally transformed biomedical research and therapeutic development, providing new paradigms for treating human diseases.

Nobel Prize Recognition

The profound significance of the ubiquitin-proteasome system was recognized with the award of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose for their pioneering work in discovering this fundamental biological system [1]. The Nobel Committee highlighted how their research revealed one of the most important regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotic cells, with far-reaching implications for understanding disease processes.

Therapeutic Targeting of the UPS

The UPS has emerged as a major therapeutic target across multiple disease areas:

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Drugs like bortezomib (Velcade) directly inhibit the proteasome's proteolytic activity and have become mainstays in the treatment of multiple myeloma [5].

- Targeted Protein Degradation: The revolutionary PROTAC (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimera) technology creates bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases to specific target proteins, inducing their degradation [7] [6]. This approach has expanded the "druggable genome" by targeting proteins previously considered undruggable.

- Molecular Glue Degraders: Compounds that induce novel interactions between E3 ligases and target proteins, leading to targeted degradation [6].

- Immunoproteasome Inhibitors: Selective inhibitors targeting the immunoproteasome for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases [1].

The field continues to evolve with emerging approaches such as Degrader-Antibody Conjugates (DACs), which combine the cell-type specificity of antibodies with the catalytic efficiency of protein degraders to minimize off-target effects [6].

The journey from the observation of a mysterious "heat-stable polypeptide" to the elucidation of the sophisticated ubiquitin-proteasome system represents one of the most compelling narratives in modern biochemistry. This discovery transformed our understanding of how cells control protein turnover, moving from a view of degradation as a bulk process to recognizing it as an exquisitely regulated mechanism central to virtually all cellular functions. The continued exploration of this system—from its fundamental mechanisms to its therapeutic exploitation—stands as a testament to the power of basic scientific research to revolutionize biology and medicine.

The discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) fundamentally reshaped our understanding of cellular protein homeostasis, earning Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 [8]. Their pioneering work in the late 1970s and 1980s, utilizing biochemical approaches with reticulocyte lysates, revealed a sophisticated ATP-dependent proteolytic system [8]. At the heart of this system is a highly coordinated, three-enzyme cascade that conjugates the small protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, thereby marking them for their eventual fate—most famously, degradation by the proteasome [9]. This enzymatic cascade, composed of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes, ensures the precise spatiotemporal control of protein degradation, a process now known to regulate virtually all aspects of eukaryotic biology [9].

The historical context of UPS research illustrates a journey from fundamental biochemical discovery to the recognition of its profound therapeutic potential. Initially focused on basic mechanisms of protein turnover, the field has expanded to elucidate the system's critical roles in cell cycle control, DNA repair, immune regulation, and signaling [10] [11] [9]. Dysregulation of the UPS is implicated in numerous human diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune dysfunctions, making its components attractive targets for drug development [11] [9]. This article provides an in-depth technical guide to the core enzymatic cascade of ubiquitination, framing it within its historical discovery and highlighting the experimental approaches that continue to drive this revolutionary field forward.

The Core Enzymatic Cascade: A Three-Step Mechanism

The ubiquitination of a protein substrate is the result of a sequential, energy-dependent process involving three distinct enzymes. The following diagram illustrates the complete sequence of this enzymatic cascade.

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme

The cascade initiates with a single E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, which acts as the master regulator of the pathway. The E1 enzyme utilizes ATP to activate ubiquitin for conjugation through a two-step mechanism [12]:

- Adenylation: The E1 enzyme binds both ATP and ubiquitin, catalyzing the adenylation of the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin, forming a ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate and releasing pyrophosphate.

- Thioester Formation: The adenylated ubiquitin is then transferred to a specific cysteine residue within the E1 active site, forming a high-energy E1~Ub thioester bond. This reaction is driven by ATP hydrolysis, making the initial step irreversible and highly favorable [12].

Structural studies reveal that E1 enzymes undergo remarkable conformational changes during this process. The Cys domain rotates approximately 130 degrees to bring the catalytic cysteine into proximity with the ubiquitin carbonyl carbon, a process termed 'active site remodeling' [12]. The E1 enzyme, now charged with ubiquitin, is primed to interact with an E2 conjugating enzyme.

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme

The second step involves the transfer of activated ubiquitin from E1 to an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme:

- E2 Recruitment and Transthiolation: The E1~Ub thioester complex recruits one of dozens of potential E2 enzymes. The E2 active site cysteine then nucleophilically attacks the E1~Ub thioester bond, resulting in a transthiolation reaction that forms an E2~Ub thioester complex [12] [13].

- Structural Interface: The E1-E2 interaction is combinatorial, involving recognition of the E2 by both the E1 ubiquitin-fold domain (UFD) and the E1 Cys domain. This dual interface ensures fidelity in pairing and efficient thioester transfer [12].

The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2 enzymes, which exhibit varying degrees of specificity for different E3 ligases and can influence the type of ubiquitin chain formed on the substrate [13].

E3: Ubiquitin Ligase

The final and most diverse step is mediated by an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which provides substrate specificity to the pathway. There are two primary mechanistic classes of E3 ligases:

- RING-type E3 Ligases: The vast majority of E3s contain a RING (Really Interesting New Gene) domain. These E3s function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind the E2~Ub complex and the substrate protein. They facilitate the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate, typically without forming a covalent E3-ubiquitin intermediate [13].

- HECT-type E3 Ligases: A smaller class of E3s contains a HECT (Homology to E6-AP C Terminus) domain. These enzymes utilize a two-step mechanism. First, ubiquitin is transferred from the E2 to a catalytic cysteine within the HECT domain, forming an E3~Ub thioester intermediate. Second, the E3 directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from itself to the substrate [14] [13].

The human genome encodes over 600 E3 ligases, allowing for exquisite specificity in the recognition of thousands of distinct protein substrates [13]. This diversity enables the UPS to regulate nearly every cellular process.

Quantitative Landscape of the Ubiquitin System

The following tables summarize key quantitative aspects of the ubiquitin enzymatic cascade, highlighting the diversity of its components and the functional outcomes of different ubiquitin linkages.

Table 1: Enzymatic Components of the Human Ubiquitin System

| Component | Number of Genes (Human) | Key Functional Features |

|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating Enzyme) | 2 | Single E1 for ubiquitin; ATP-dependent; forms thioester with Ub [13] |

| E2 (Conjugating Enzyme) | ~40 | Transient E2~Ub thioester; influences chain topology [13] |

| E3 (Ligase Enzyme) | 600+ | Provides substrate specificity; RING-type (direct transfer) vs. HECT-type (covalent intermediate) [13] |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | ~100 | Cleaves ubiquitin from substrates; proofreading and ubiquitin recycling [10] |

Table 2: Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Functional Consequences

| Ubiquitin Linkage Type | Primary Function | Prototypical E3 Ligase(s) |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [10] [11] | APC/C, SCF complexes [13] |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation; ER-associated degradation (ERAD) [11] | UBR1, UBR2, CHIP [11] |

| K63-linked | Non-proteolytic signaling (DNA repair, inflammation, endocytosis) [10] [11] | TRAF6, CHIP, ITCH [11] |

| Met1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB activation and inflammatory signaling [9] | LUBAC complex [9] |

| Monoubiquitination | Endocytosis, histone regulation, protein trafficking [13] | C-Cbl (EGFR endocytosis) [13] |

Substrate Recognition: The Critical Role of E3 Ligases and Degrons

E3 ubiquitin ligases achieve substrate specificity by recognizing specific degradation signals, or degrons, on their target proteins. The following diagram maps the primary degron recognition pathways used by E3 ligases to identify their substrates.

The molecular mechanisms of degron recognition are highly sophisticated:

- Phosphodegrons: Many E3s, particularly those within the SCF (Skp1-Cul1-F-box) complex, recognize substrates only after a specific serine, threonine, or tyrosine residue has been phosphorylated. For example, the F-box protein FBW7 uses arginine residues to form hydrogen bonds with the phosphate group on its substrates, stabilizing the E3-substrate interaction [13].

- Oxygen-Dependent Degrons: The von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) E3 ligase complex recognizes the transcription factor HIF-α only under normal oxygen conditions when a specific proline residue in HIF-α is hydroxylated. Under hypoxic conditions, this modification does not occur, and HIF-α escapes degradation, allowing it to activate hypoxic response genes [13].

- N-degrons: The N-end rule pathway relates the half-life of a protein to the identity of its N-terminal residue. E3 ligases known as N-recognins bind to destabilizing N-terminal residues (e.g., Arg, Lys, His, Phe, Trp, Tyr) that are often exposed after proteolytic cleavage [13].

- Misfolding Recognition: E3 ligases involved in protein quality control, such as San1 in yeast or CHIP in mammals, can recognize exposed hydrophobic patches or other structural features characteristic of misfolded proteins. Some of these E3s, like San1, even possess disordered regions that facilitate binding to a wide variety of misfolded clients [13].

Key Experimental Methodologies and Reagents

Understanding the UPS cascade has been driven by specific biochemical and cell-based assays. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments that have elucidated the mechanism.

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

This foundational biochemical assay reconstitutes the ubiquitination cascade using purified components to study the mechanism directly [14].

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Combine in a test tube: 50-100 nM E1 enzyme, 1-2 µM E2 enzyme, 0.5-1 µM E3 ligase, 10-20 µM ubiquitin, 1-2 mM ATP, 5-10 mM MgCl₂, and an energy-regenerating system (e.g., creatine phosphate/creatine kinase). Include the substrate protein at a concentration of 1-5 µM.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 60-90 minutes.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer (with or without a reducing agent like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol). Analyze the products by Western blotting using an antibody against the substrate or ubiquitin. The formation of higher molecular weight smears indicates mono- or polyubiquitination of the substrate.

Key Insight: The requirement for all three enzymes (E1, E2, E3) and ATP can be tested by omitting each component individually. Furthermore, the use of a reducing agent can break thioester bonds (E1~Ub and E2~Ub), but not isopeptide bonds (substrate-Ub), allowing these intermediates to be distinguished [14].

Thioester Intermediate Analysis

This experiment directly demonstrates the formation of covalent E2~Ub and E3~Ub thioester intermediates, which is a hallmark of the HECT-type E3 ligase mechanism [14].

Procedure:

- Charging Reactions: Set up two separate reactions. The first contains E1, E2, ubiquitin, and ATP. The second contains E1, a HECT E3 (like E6-AP), ubiquitin, and ATP.

- Non-reducing Gel Electrophoresis: Terminate the reactions with SDS-PAGE loading buffer that lacks a reducing agent (omit DTT/β-mercaptoethanol).

- Detection: Perform Western blotting using an anti-ubiquitin antibody. The presence of a band corresponding to the molecular weight of E2 + Ub or E3 + Ub indicates a stable thioester intermediate. This band should disappear when the experiment is repeated under reducing conditions, which cleave the thioester bond.

Historical Context: This methodology was used in the seminal 1995 paper on E6-AP to prove it forms a ubiquitin thioester, establishing that some E3s have direct enzymatic activity rather than functioning merely as scaffolds [14].

Reporter-Based Activity Measurement in Cells

Reporter constructs are used to monitor UPS activity in living cells, providing a tool for high-throughput screening of inhibitors or studying UPS function in disease models [10].

Common Reporters:

- GFPu: This reporter consists of a stable protein (e.g., Green Fluorescent Protein, GFP) fused to a potent degron, such as the CL1 degron. In cells, GFPu is constitutively synthesized and rapidly degraded by the UPS, resulting in low fluorescence. Inhibition of the proteasome (e.g., with Bortezomib) or the ubiquitin cascade leads to GFPu accumulation and increased cellular fluorescence, which is quantifiable by microscopy or flow cytometry [10].

- Ubᵉâ¸â·â¶áµ›-GFP: A non-cleavable ubiquitin mutant (G76V) is fused to GFP. This single ubiquitin acts as a primer for the formation of a polyubiquitin chain, efficiently targeting the reporter for degradation. Its degradation is less dependent on specific E3 ligases compared to degron-based reporters [10].

Application: These reporters have been used in transgenic animal models to investigate UPS activity in aging and neurodegenerative diseases, helping to test hypotheses about proteasome impairment in conditions like Huntington's disease [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying the Ubiquitin Cascade

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib, MG-132) | Blocks degradation of ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome, causing their accumulation. | Validating UPS-dependent substrate degradation; studying the effects of blocked proteolysis [10]. |

| ATP-depleting Systems | Depletes ATP, which is essential for E1-mediated ubiquitin activation. | Serves as a negative control in in vitro ubiquitination assays to demonstrate ATP dependence [14]. |

| Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme (E1) Inhibitor (e.g., PYR-41) | Specifically inhibits the E1 enzyme, blocking the entire ubiquitination cascade upstream. | Investigating the functional consequences of global ubiquitination inhibition in cells [9]. |

| UPS Reporters (e.g., GFPu, Ubᵉâ¸â·â¶áµ›-GFP) | Fluorescent protein fusions designed for rapid UPS-mediated degradation. | Measuring global UPS activity in live cells via fluorescence; high-throughput drug screening [10]. |

| Activity-Based Probes for DUBs | Irreversibly bind to active deubiquitinases (DUBs) for their identification and characterization. | Profiling active DUBs in cell lysates; studying DUB function and inhibitor specificity [10]. |

| C13H14BrN3O4 | C13H14BrN3O4, MF:C13H14BrN3O4, MW:356.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Quinoline, 2-((chloromethyl)thio)- | Quinoline, 2-((chloromethyl)thio)-, CAS:62601-19-8, MF:C10H8ClNS, MW:209.70 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The demystification of the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade, beginning with foundational biochemical work, has revealed a complex regulatory system of extraordinary scope and specificity. The historical journey from initial discovery in reticulocyte lysates to the current molecular-level understanding, powered by structural biology and sophisticated cellular assays, stands as a testament to the power of basic scientific research [14] [8].

The profound understanding of this cascade has opened up entirely new therapeutic frontiers. The clinical success of the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib in treating multiple myeloma validated the UPS as a druggable system [10]. Today, the field is rapidly advancing beyond proteasome inhibition to target the system with greater precision. Strategies now focus on E3 ligases themselves, leveraging their intrinsic specificity to target pathogenic proteins for degradation [11] [15]. Technologies such as PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) and molecular glues represent a paradigm shift in drug discovery. These bifunctional molecules hijack the endogenous E3 machinery to selectively degrade protein targets previously considered "undruggable," ushering in a new era of targeted protein degradation [11] [15]. As we continue to decipher the nuances of the ubiquitin code, the enzymatic cascade discovered decades ago promises to yield transformative therapies for cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and immune disorders for years to come.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents the primary pathway for targeted intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, a process fundamental to virtually all cellular processes. The discovery of this system, which earned the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose, revolutionized our understanding of how cells control protein turnover [1] [2]. Before this discovery, protein degradation was largely attributed to lysosomes, but pioneering work in the late 1970s revealed a separate, energy-dependent proteolytic pathway in reticulocytes (which lack lysosomes), hinting at a more complex degradation machinery [1] [2]. The term "proteasome" was coined after the identification of a multi-catalytic proteinase complex, which was later understood to function in concert with ubiquitin tagging [1] [16]. This historical foundation underscores the proteasome's role as a sophisticated cellular machine, essential for maintaining protein homeostasis and regulating countless physiological processes.

Architectural Organization of the Proteasome

The 20S Core Particle (CP)

The 20S core particle serves as the catalytic heart of the proteasome. This barrel-shaped complex exhibits a highly conserved α7β7β7α7 ring structure, comprising four stacked heptameric rings [1] [16] [17]. The two outer rings are formed by seven distinct α-subunits that function as a gated channel, controlling substrate entry into the proteolytic chamber. The two inner rings are composed of seven β-subunits, three of which (β1, β2, and β5) contain the catalytic threonine residues responsible for the proteasome's peptidylglutamyl-peptide-hydrolyzing, trypsin-like, and chymotrypsin-like activities, respectively [16] [18]. The interior chamber of the 20S CP measures approximately 53 Å in width, with entry pores as narrow as 13 Å, necessitating substrate unfolding before degradation [1].

Table 1: Catalytic Subunits of the Standard 20S Core Particle and the Immunoproteasome

| Subunit Type | Standard Proteasome | Immunoproteasome | Catalytic Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-like | β1 (PSMB6) | β1i (PSMB9/LMP2) | Cleavage after acidic residues |

| Trypsin-like | β2 (PSMB7) | β2i (PSMB10/MECL1) | Cleavage after basic residues |

| Chymotrypsin-like | β5 (PSMB8) | β5i (PSMB8/LMP7) | Cleavage after hydrophobic residues |

Regulatory Particles and Proteasome Diversity

The 20S core particle can be activated by various regulatory complexes that cap one or both ends, enabling substrate recognition, unfolding, and translocation.

- 19S Regulatory Particle (RP): The primary regulator, forming the 26S proteasome (when one 19S RP is attached) or the 30S proteasome (when two are attached) [16]. The 19S RP is further divided into:

- The Base: Contains six AAA-ATPase (Rpt1-6) subunits and three non-ATPases (Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn13). This subcomplex is responsible for substrate recognition, deubiquitination, unfolding, and gate opening [17] [18].

- The Lid: Comprises at least nine non-ATPase subunits (Rpn3, 5-9, 11, 12, 15) that facilitate the removal of ubiquitin chains before substrate degradation [17].

- Immunoproteasome: In immune cells, the constitutive catalytic β-subunits can be replaced by inducible counterparts (β1i, β2i, and β5i) upon exposure to pro-inflammatory signals like interferon-gamma [19] [1]. The immunoproteasome often associates with the 11S regulator (PA28), which enhances the production of antigenic peptides for MHC class I presentation [19] [18].

- Other Regulators: Additional regulators include PA200/Blm10 and PI31, which can modulate proteasome activity in specific tissues or under certain conditions [19] [16].

The following diagram illustrates the overall structure and composition of the 26S proteasome.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway: A Stepwise Mechanism

Protein degradation by the proteasome is a tightly controlled, multi-step process initiated by the covalent attachment of a ubiquitin chain to the target protein.

Ubiquitin Tagging: A three-enzyme cascade mediates substrate ubiquitination.

- E1 (Ubiquitin-activating enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner [19] [20].

- E2 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme): Accepts the activated ubiquitin from E1 [19] [20].

- E3 (Ubiquitin ligase): Recognizes specific substrate proteins and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate. The human genome encodes hundreds of E3 ligases, providing exquisite substrate specificity [19] [16]. Repetition of this process builds a polyubiquitin chain, most commonly linked through lysine 48 (K48) of ubiquitin, which serves as the primary degradation signal [19] [17].

Substrate Recognition and Processing: The polyubiquitinated substrate is recognized by ubiquitin receptors (e.g., Rpn10 and Rpn13) within the 19S RP [17]. The substrate is then unfolded by the ATP-dependent motor of the Rpt1-6 ring. The integral deubiquitinase Rpn11 removes the ubiquitin chain for recycling, and the unfolded polypeptide is translocated into the catalytic chamber of the 20S CP for degradation [17].

Degradation and Product Release: Within the 20S core, the polypeptide is cleaved into short peptides (typically 7-9 amino acids long). These peptides are released into the cytosol and can be further degraded to amino acids by other cellular proteases or used for antigen presentation [1].

The workflow of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is summarized in the diagram below.

Experimental Methodologies for Proteasome Research

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Proteasome Studies

| Reagent / Method | Function / Target | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Peptide Aldehydes (e.g., MG132) | Reversible inhibitor of proteasome catalytic sites [18] | Early-stage research; studying proteasome inhibition effects in cells. |

| Peptide Boronates (e.g., Bortezomib) | High-affinity, reversible inhibitor (primarily β5 subunit) [18] | Clinical therapy (myeloma, lymphoma); mechanistic biochemistry. |

| PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) | Bifunctional molecules recruiting E3 ligase to non-native target protein [21] | Targeted protein degradation; drug discovery for "undruggable" targets. |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies (K48-linkage specific) | Immunoaffinity enrichment of K48-polyubiquitinated proteins [22] | Ubiquitinomics; identifying endogenous proteasome substrates. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) with DiGly Antibody Enrichment | Proteome-wide identification of ubiquitination sites [22] | Systems biology of UPS; quantifying changes in ubiquitination. |

Protocol: Analysis of Proteasome Activity and Inhibition

This protocol outlines a standard method for evaluating proteasome function and the efficacy of inhibitory compounds.

Cell Lysis and Proteasome Isolation:

- Harvest cells and lyse using a non-ionic detergent-based buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM DTT) to maintain complex integrity.

- Clarify the lysate by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- The 26S proteasome can be partially purified from the supernatant via ultracentrifugation or affinity-based methods.

Activity Assay:

- Incubate proteasome-containing samples with fluorogenic peptide substrates in an assay buffer (e.g., 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgClâ‚‚, 1 mM DTT).

- Use substrate-specific peptides: Suc-LLVY-AMC for chymotrypsin-like (β5) activity, Boc-LRR-AMC for trypsin-like (β2) activity, and Z-LLE-AMC for caspase-like (β1) activity. Cleavage releases the fluorescent AMC group.

- For inhibitor testing, pre-incubate the proteasome sample with the compound (e.g., 1-1000 nM bortezomib) for 15-30 minutes before adding the substrate.

Quantification and Analysis:

- Measure fluorescence (excitation ~380 nm, emission ~460 nm) kinetically over 30-60 minutes using a plate reader.

- Calculate enzyme velocity from the linear phase of the reaction. Determine ICâ‚…â‚€ values for inhibitors by fitting velocity data against inhibitor concentration using a non-linear regression model.

Assembly of the Proteasome Complex

The biogenesis of the 26S proteasome is a sophisticated process facilitated by dedicated assembly chaperones, which prevent off-pathway aggregation and ensure the correct stoichiometric incorporation of subunits [23].

20S Core Particle Assembly: Assembly begins with the formation of the α-ring, guided by chaperones PAC1-PAC2 and PAC3-PAC4 heterodimers, which ensure the correct ordering of α-subunits [23]. The β-subunits are then incorporated onto the α-ring with the assistance of the intramolecular chaperone Ump1, forming a half-proteasome. Two half-proteasomes dimerize to form the mature 20S core particle, a step that triggers the self-activation of β-subunits by propeptide cleavage and the degradation of Ump1 [23].

19S Regulatory Particle Assembly: The assembly pathway of the 19S RP is less well-characterized but is known to involve several modular subcomplexes. The base and lid assemble separately before combining, a process that requires additional non-ATPase factors to form a functional RP capable of docking onto the 20S CP [17] [23].

The chaperone-mediated assembly of the 20S proteasome is depicted below.

Therapeutic Targeting of the Proteasome

The proteasome has been successfully validated as a drug target, particularly in hematologic malignancies. Bortezomib (Velcade), a first-in-class dipeptide boronate inhibitor, reversibly targets the chymotrypsin-like activity of the β5 subunit [18]. It is approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. Bortezomib's mechanism of action involves disrupting essential cellular processes in malignant cells, including NF-κB signaling by preventing the degradation of its inhibitor, IκBα [19] [18]. This leads to an accumulation of pro-apoptotic proteins and cell cycle arrest.

A more recent revolutionary approach is the development of PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras). These heterobifunctional molecules consist of one ligand that binds a target protein of interest, another that recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase (e.g., VHL or CRBN), and a linker connecting them [21]. By bringing the E3 ligase into proximity with a non-native substrate, PROTACs induce its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome. This technology has expanded the druggable genome, allowing targeting of proteins previously considered "undruggable." Examples in clinical development for hematologic malignancies include NX-2127 (a BTK degrader) and SIAIS178 (a BCR-ABL degrader) [21].

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) represents one of the most sophisticated regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotic cells, governing the selective degradation of intracellular proteins. For decades, protein degradation was considered a nonspecific, scavenging process, while protein synthesis was recognized as the primary site of cellular regulation. This perspective shifted dramatically with the discovery that ATP-dependent protein degradation selectively targeted abnormal and short-lived regulatory proteins [24]. The resolution of this paradox—that energy-dependent degradation enables exquisite specificity—formed the foundation of UPS research. The seminal work of Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose, recognized by the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, established the fundamental biochemical principles of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis [25], revealing a complex system that controls countless cellular processes, from cell cycle progression to DNA repair and immune response.

Foundational Discoveries: Mapping the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway

The elucidation of the UPS pathway resulted from a series of interconnected experiments that progressively revealed its components and mechanisms. Key milestones are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in UPS Pathway Elucidation

| Year | Key Discovery | Experimental System | Principal Investigators | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | Isolation of Ubiquitin | Calf thymus tissue | Gideon Goldstein | Identification of a universal, heat-stable polypeptide later named ubiquitin [24]. |

| 1977 | ATP-Dependent Proteolysis | Reticulocyte cell-free extract | Alfred Goldberg et al. | Established an in vitro system for energy-dependent protein degradation [24]. |

| 1978 | Identification of APF-1 | Fractionated reticulocyte extract | Ciechanover & Hershko | Discovery of ATP-dependent, heat-stable factor (APF-1, later ubiquitin) essential for proteolysis [24]. |

| 1980 | Covalent Binding & Polyubiquitination | Reticulocyte extract | Ciechanover, Hershko, Rose | Demonstrated covalent attachment of APF-1 to substrate proteins and formation of polyubiquitin chains—the "kiss of death" [24]. |

| 1981-1983 | E1-E2-E3 Enzymatic Cascade | Biochemical reconstitution | Ciechanover, Hershko, Rose | Proposed and validated the multi-step enzymatic cascade for substrate ubiquitination [24]. |

| 1980s-1990s | Physiological Substrates & Functions | Various mutant cell lines | Multiple groups | Linked UPS to cell cycle control, DNA repair, and immune response (e.g., p53 degradation) [24] [26]. |

| 2004 | Nobel Prize in Chemistry | - | Ciechanover, Hershko, Rose | Recognition of the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation [25]. |

The Energy Dependence Paradox and Early Experimental Systems

The initial breakthrough stemmed from investigating a fundamental biochemical contradiction. While digestive protein degradation (e.g., by trypsin) requires no energy, early experiments in the 1950s indicated that the breakdown of the cell's own proteins is energy-dependent [24]. This observation remained unexplained for decades. A critical experimental advance came in 1977 when Goldberg and his colleagues developed a cell-free extract from reticulocytes (immature red blood cells) that could catalyze the ATP-dependent breakdown of abnormal proteins [24]. This in vitro system provided the essential tool for dissecting the pathway biochemically, without the complexity of a living cell.

The Discovery of APF-1 and the Ubiquitin Tag

Using the reticulocyte extract, Ciechanover and Hershko made a pivotal discovery in 1978. When they separated the extract using chromatography, they found it divided into two fractions, neither of which was active alone, but ATP-dependent proteolysis resumed when the fractions were recombined [24]. They identified the active component in one fraction as a small, heat-stable polypeptide with a molecular weight of approximately 9,000 Da, which they named APF-1 (Active Principle in Fraction 1). This protein was later confirmed to be ubiquitin [24].

The decisive biochemical insight came in 1980. Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose demonstrated that APF-1 was not just a cofactor but was covalently bound to target proteins via a stable chemical bond [24]. Furthermore, they observed that multiple APF-1 molecules could be attached to a single target protein, a phenomenon they termed polyubiquitination [24]. This was the "kiss of death"—the signal that marked a protein for destruction.

Elucidating the Enzymatic Cascade: E1, E2, and E3

Between 1981 and 1983, the same researchers deciphered the enzymatic machinery responsible for ubiquitin conjugation. They established the multi-step ubiquitin-tagging hypothesis, involving three distinct enzyme classes [24]:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction.

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): Accepts the activated ubiquitin from E1.

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): Recognizes specific substrate proteins and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the substrate, often forming a polyubiquitin chain.

This cascade allows for tremendous specificity, primarily determined by the hundreds of different E3 ligases that recognize distinct sets of substrate proteins [24] [26].

The Proteasome: Identification of the Cellular "Waste Disposer"

The final component of the pathway, the proteasome, was identified as the structure that recognizes and degrades polyubiquitinated proteins. A human cell contains roughly 30,000 of these barrel-shaped complexes [24]. The proteasome's active sites are sequestered inside its barrel, and access is controlled by a "lock" that recognizes the polyubiquitin tag. The proteasome denatures the target protein using ATP, removes the ubiquitin tag for recycling, and degrades the protein into short peptides [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocols of Foundational UPS Studies

Protocol 1: Fractionation of Reticulocyte Extract and Discovery of APF-1

This protocol outlines the key experiment that led to the identification of ubiquitin (APF-1) as an essential factor for ATP-dependent protein degradation [24].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Reticulocyte Extract Fractionation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Reticulocytes (Rabbit) | Source for creating the cell-free extract. These cells are highly specialized for protein degradation. |

| DEAE-Cellulose Chromatography | Ion-exchange chromatography resin used to separate the reticulocyte extract into two fractions (I and II). |

| ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) | The cell's energy currency, required to drive the ubiquitination reaction and proteasomal degradation. |

| Radioactively Labeled Protein Substrate (e.g., ³âµS-labeled lysozyme) | A model substrate whose degradation can be tracked by measuring the release of acid-soluble radioactivity. |

| ATP-Regenerating System | A cocktail of enzymes (e.g., creatine phosphokinase) and substrates (e.g., creatine phosphate) that maintains a constant level of ATP in the reaction. |

Methodology:

- Preparation of Crude Extract: Reticulocytes from anemic rabbits are lysed, and a post-mitochondrial supernatant is prepared to create a crude cell-free extract.

- Chromatographic Fractionation: The crude extract is applied to a DEAE-cellulose column. The large bulk of hemoglobin, which interfered with the assays, was not retained. The column was then eluted with a salt gradient, separating the extract into two key fractions:

- Fraction I: Contained the small, heat-stable protein APF-1 (later identified as ubiquitin).

- Fraction II: Contained the enzymatic machinery required for conjugation and degradation.

- Reconstitution Assay: The degradation of the radioactively labeled substrate is tested in separate tubes containing:

- Fraction I only.

- Fraction II only.

- Fraction I + Fraction II.

- All tubes are supplemented with ATP and an ATP-regenerating system.

- Measurement of Degradation: After incubation, the reaction is stopped with trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The amount of protein degraded is quantified by measuring the radioactivity in the TCA-soluble supernatant, which represents peptides and amino acids.

Interpretation: Proteolysis occurred only in the tube containing both fractions, demonstrating that APF-1 in Fraction I was an essential, discrete component of the ATP-dependent proteolytic pathway.

Protocol 2: Demonstration of Covalent Ubiquitin-Protein Conjugation

This critical experiment provided the first evidence that APF-1/ubiquitin forms a covalent bond with substrate proteins [24].

Methodology:

- Incubation Setup: The reconstituted system (Fraction I + Fraction II) is incubated with radioactively labeled substrate and ATP.

- SDS-PAGE Analysis: At timed intervals, samples are taken, and the reaction is stopped. The proteins are separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), which resolves proteins based on molecular weight.

- Autoradiography: The gel is subjected to autoradiography to visualize the radioactive proteins.

Interpretation: In addition to the band for the substrate protein, the autoradiograph revealed a ladder of new, higher molecular weight bands. These bands represented substrate proteins with increasing numbers of APF-1 molecules attached. This provided direct visual evidence for the covalent conjugation and polyubiquitination of target proteins, the central signal for degradation.

The UPS Enzymatic Cascade: A Modern Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the modern understanding of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, built upon the foundational discoveries.

Diagram 1: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) Enzymatic Cascade. This pathway depicts the sequential action of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes to tag a target protein with a polyubiquitin chain, which is then recognized and degraded by the proteasome in an ATP-dependent process.

The historical mapping of the UPS pathway represents a triumph of biochemical investigation. What began as the resolution of an energy-dependence paradox evolved into the discovery of a universal regulatory system. The key experiments—fractionation of reticulocyte extracts, demonstration of covalent ubiquitin conjugation, and elucidation of the E1-E2-E3 cascade—provided the mechanistic framework that underpins our current understanding. This knowledge has been transformative, revealing the UPS's critical role in health and disease. The system's importance is highlighted by the clinical success of proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib, in treating cancers like multiple myeloma [26], and the ongoing development of therapies targeting specific E3 ligases. The foundational work of Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose not only unveiled a fundamental cellular process but also opened a vast new frontier for drug discovery and therapeutic intervention.

The Ubiquitin Proteasome System (UPS) represents a fundamental and essential pathway for maintaining protein homeostasis within eukaryotic cells. This sophisticated system orchestrates the controlled degradation of intracellular proteins, thereby influencing a vast array of cellular processes, including the cell cycle, gene expression, DNA repair, and responses to cellular stress [27] [1]. At its core, the UPS involves the covalent attachment of a small, highly conserved protein—ubiquitin—to target substrate proteins, which in most cases marks them for destruction by the 26S proteasome [28]. The discovery of this system and its intricate mechanics, which earned the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 for Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose, revolutionized our understanding of protein turnover, moving beyond the view of the lysosome as the primary degradation site to recognize an ATP-dependent, non-lysosomal proteolytic pathway [1] [2].

The importance of the UPS extends far beyond mere waste disposal. It acts as a critical regulatory mechanism, with its dysfunction being implicated in numerous human diseases, particularly cancers and neurodegenerative disorders [29] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the UPS is not only about grasping a basic physiological process but also about identifying novel therapeutic targets. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the ubiquitin molecule, the mechanics of the UPS, its historical context, and the contemporary experimental tools used to probe its function, thereby framing our current knowledge within the rich history of its discovery.

The Ubiquitin Molecule: Structure, Function, and Diversity of Signals

Ubiquitin is a compact, 76-amino acid protein with a molecular weight of approximately 8.5 kDa that is remarkably conserved across all eukaryotes [30] [31]. Its structure is characterized by a stable β-grasp fold, which presents several key residues critical for its function. The C-terminus of ubiquitin ends in a glycine-glycine (Gly-Gly) motif, and the C-terminal glycine is the site of activation and conjugation [28]. The molecule also contains seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63), which serve as potential attachment points for additional ubiquitin molecules, enabling the formation of polyubiquitin chains [30] [31].

The functional outcome of ubiquitylation is profoundly determined by the type of ubiquitin modification:

- Monoubiquitylation: The attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to a substrate lysine. This can alter the protein's activity, localization, or interactions, and is involved in processes like histone regulation and endocytosis [30].

- Multi-monoubiquitylation: The attachment of single ubiquitin molecules to multiple lysine residues on the same substrate.

- Polyubiquitylation: The formation of a chain of ubiquitin molecules linked through one of the seven lysine residues or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of the preceding ubiquitin. The topology of the chain dictates a specific signaling outcome [32] [33]:

- K48-linked chains: The most well-characterized linkage, primarily targeting the modified substrate for degradation by the 26S proteasome [1].

- K63-linked chains: Generally involved in non-proteolytic signaling pathways, such as DNA repair, inflammation, and endocytosis [32].

- Other linkages (K11, K29, etc.) are being increasingly understood to play distinct roles in degradation and signaling, adding immense complexity to the ubiquitin code [22].

Recent structural biology efforts, encompassing X-ray crystallography, NMR, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), have provided deep insights into how these different chain linkages are recognized by specific receptors and effector proteins, dictating the downstream fate of the modified substrate [33].

Historical Context and Key Discoveries of the UPS

The elucidation of the UPS is a testament to systematic biochemical investigation. The journey began in the late 1970s and early 1980s, challenging the prevailing notion that lysosomes were the primary site for intracellular protein degradation.

Table 1: Historical Milestones in UPS Discovery

| Year/Period | Key Discovery | Lead Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1977-1978 | Identification of an ATP-dependent proteolytic system in reticulocytes (which lack lysosomes) [1]. | Goldberg, Etlinger [1] | Provided the first evidence of a non-lysosomal degradation pathway. |

| Late 1970s | Discovery of a heat-stable polypeptide (APF-1) essential for ATP-dependent proteolysis; later identified as ubiquitin [1] [2]. | Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose [27] [2] | Isolated the key component of the system and established its fundamental role. |

| Early 1980s | Reconstitution of the ubiquitination cascade and identification of the three-enzyme sequence (E1, E2, E3) [27]. | Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose [27] | Defined the core enzymatic mechanism of the pathway. |

| Mid-1980s | Discovery that a polyubiquitin chain (specifically K48-linked) is the signal for proteasomal degradation [1]. | Hershko, Varshavsky | Established the molecular code for protein targeting to the proteasome. |

| 1990s | Solving the first X-ray crystal structure of the 20S proteasome [1]. | Multiple groups | Provided atomic-level insight into the degradation machine. |

| 2004 | Award of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation [1] [28]. | Ciechanover, Hershko, Rose | Formal recognition of the paradigm-shifting nature of the discovery. |

| 2010s-Present | High-resolution cryo-EM structures of the entire 26S proteasome, detailed mechanistic studies of E3 ligases, and development of targeted protein degradation drugs [1] [2]. | Multiple groups | Pushing the frontiers towards therapeutic application and systems-level understanding. |

The collaborative work, particularly between Hershko's laboratory at the Technion and Rose's at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, was instrumental in piecing together the enzymatic cascade [1] [2]. A pivotal conceptual advance was the understanding that ATP hydrolysis was required not for proteolysis itself, but for the prior conjugation of ubiquitin to the target protein, forming a multi-ubiquitin chain that serves as a recognition signal [27] [2].

The Core Mechanism: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is a sequential process catalyzed by three families of enzymes, culminating in the degradation of the target protein by the proteasome.

The Enzymatic Cascade: E1, E2, and E3

- Activation (E1): The process initiates with a single E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme. It uses ATP to adenylate the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin, forming a high-energy thioester bond between ubiquitin and a cysteine residue in its own active site [28]. This step activates ubiquitin for transfer.

- Conjugation (E2): The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the catalytic cysteine of one of several dozen E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (also called UBCs) [30] [28].

- Ligation (E3): Finally, an E3 ubiquitin ligase (numbering in the hundreds) facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine ε-amino group on the target protein, forming an isopeptide bond [30] [28]. The E3 ligase is primarily responsible for substrate recognition, providing the system with its immense specificity. There are two major classes of E3s: RING ligases, which act as scaffolds to bring the E2~Ub and substrate together, and HECT ligases, which form a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [2].

This cycle repeats to build a polyubiquitin chain on the substrate. The following diagram illustrates this enzymatic cascade:

The 26S Proteasome: The Degradation Machine

The 26S proteasome is a massive 2.5 MDa multi-subunit complex responsible for the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins [1] [28]. It is composed of two primary entities:

- 20S Core Particle (CP): A barrel-shaped structure composed of four stacked heptameric rings. The two outer rings are made of α-subunits that control gated access to the interior. The two inner rings are made of β-subunits that contain the proteolytic active sites, facing an enclosed inner chamber. This architecture ensures that proteins are degraded in a compartmentalized manner, preventing uncontrolled proteolysis in the cytoplasm [1].

- 19S Regulatory Particle (RP): One or two 19S particles cap the ends of the 20S core. The 19S RP is responsible for recognizing polyubiquitinated substrates, removing the ubiquitin chain (via deubiquitinating enzymes, or DUBs), unfolding the target protein in an ATP-dependent manner, and translocating the unfolded polypeptide into the 20S core for degradation [1].

The degradation process yields short peptides (typically 7-9 amino acids long), which are further degraded into amino acids by cellular peptidases and recycled for new protein synthesis. The ubiquitin molecules are also cleaved off and recycled [1] [28].

Quantitative Analysis of Ubiquitinated Proteins: An Experimental Protocol

Modern proteomics has enabled the systematic, large-scale identification and quantification of ubiquitination events. The following workflow, based on a 2019 study of human pituitary adenomas, exemplifies a standard label-free quantitative ubiquitinomics approach [30] [31].

Detailed Methodology

Sample Preparation:

- Extract total proteins from tissue (e.g., tumor vs. control) or cells.

- Denature and reduce proteins to ensure accessibility.

- Digest the protein mixture to peptides with trypsin. A key feature here is that trypsin cleaves after the two C-terminal glycine residues of ubiquitin, leaving a di-glycine (Gly-Gly) remnant with a mass shift of 114.04 Da attached to the modified lysine (ε-amino group) of the substrate-derived peptide. This K-ε-GG moiety is the signature for ubiquitination sites [30] [31].

Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Peptides:

- Due to the low stoichiometry of ubiquitinated peptides, enrichment is crucial.

- Incubate the tryptic peptide mixture with an anti-K-ε-GG antibody conjugated to beads. This antibody specifically immunoaffinity-purifies peptides containing the di-glycine remnant [30] [31].

- Wash away non-specifically bound peptides.

- Elute the enriched ubiquitinated peptides.

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS):

- Separate the enriched peptides by liquid chromatography (LC) based on hydrophobicity.

- Analyze the eluting peptides by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). The mass spectrometer first measures the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of intact peptides (MS1) and then selects precursor ions for fragmentation to generate MS2 spectra [32] [30].

Data Processing and Quantification:

- Use computational software (e.g., MaxQuant) to search the MS2 spectra against a protein sequence database.

- Identify proteins and localize the ubiquitination sites based on the presence of the di-glycine remnant and the fragmentation pattern.

- For label-free quantification (LFQ), the intensity of the precursor ion in the MS1 spectrum is used to determine the relative abundance of the ubiquitinated peptide across different samples [30] [31].

The following diagram visualizes this experimental protocol and its key outcomes:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Ubiquitin Research

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for UPS Investigation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG-132, Bortezomib) | Inhibit the proteolytic activity of the 20S proteasome, causing accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins [28]. | Validating UPS-dependent degradation; studying the effects of impaired protein turnover. |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detect global ubiquitin conjugates via Western blot, immunofluorescence, or ELISA [28]. | Assessing overall ubiquitination levels in cells or tissues under different conditions. |

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibodies | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics [30] [31]. | Identifying ubiquitination sites and quantifying changes in substrate ubiquitination. |

| Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Reagents | Isobaric labels for multiplexed relative quantification of proteins and PTMs across multiple samples in a single MS run [32]. | High-throughput profiling of ubiquitination changes across multiple experimental conditions or time points. |

| E1/E2/E3 Enzymes (Recombinant) | For in vitro reconstitution of ubiquitination reactions to study enzyme kinetics, specificity, and mechanism [28]. | Biochemical characterization of specific E3 ligase activity and substrate profiling. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Selectively inhibit DUBs to prevent ubiquitin chain editing and substrate deubiquitination [28] [2]. | Probing the role of specific DUBs in regulating ubiquitin-dependent pathways. |

| 2,6-Dimethyloct-6-en-2-yl formate | 2,6-Dimethyloct-6-en-2-yl formate, CAS:71662-24-3, MF:C11H20O2, MW:184.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ammonium gadolinium(3+) disulphate | Ammonium gadolinium(3+) disulphate, CAS:21995-31-3, MF:GdH4NO8S2, MW:367.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

UPS in Disease and Therapeutic Targeting

The critical role of the UPS in cellular regulation makes its dysfunction a contributor to many diseases. In neurodegeneration, such as in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, the accumulation of ubiquitin-positive protein aggregates is a hallmark, suggesting an impairment in UPS clearance of misfolded proteins [29] [2]. In cancer, oncoproteins are often stabilized due to decreased ubiquitination or tumor suppressors are hyper-degraded due to overactive E3 ligases [2].

This understanding has led to successful therapeutics and novel modalities:

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Drugs like Bortezomib are used clinically to treat multiple myeloma by blocking proteasomal degradation, leading to the accumulation of toxic proteins and apoptosis in cancer cells [2].

- Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD): A revolutionary approach using bifunctional molecules like PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras). A PROTAC consists of one ligand that binds an E3 ubiquitin ligase (e.g., VHL or CRBN) connected by a linker to another ligand that binds a target protein of interest (POI). This brings the E3 ligase into proximity with the POI, leading to its ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. This allows for the targeted degradation of proteins previously considered "undruggable" [2].

Ubiquitin, as a conserved molecular tag, sits at the heart of a complex and elegant system that maintains protein homeostasis. From its initial discovery as a key to ATP-dependent protein degradation to the current deep mechanistic and structural understanding, research into the UPS has continuously provided profound insights into cellular physiology. The development of sophisticated quantitative proteomic methods now allows researchers to decode the "ubiquitinome" with unprecedented precision, while the translation of this knowledge is yielding a new generation of therapeutics. For scientists and drug developers, the UPS remains a rich source of fundamental biological questions and promising clinical opportunities.

Methodological Revolutions and Therapeutic Applications in Drug Development

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), discovered approximately 40 years ago, represents one of the most intricate regulatory networks in eukaryotic cells, governing a multitude of cellular processes including protein homeostasis, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and signal transduction [22]. This system employs a sophisticated enzymatic cascade—comprising ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3)—to covalently attach ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, while deubiquitinases (DUBs) reverse this modification [34]. The resulting ubiquitin code, with its diverse topologies including monoubiquitination, multiple monoubiquitination, and various polyubiquitin chains differing in linkage types and architecture, creates enormous complexity that long challenged comprehensive analysis [35].

Mass spectrometry (MS) has emerged as a transformative technology that has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the ubiquitinome—the complete set of ubiquitin modifications within a biological system [22]. From early studies that identified mere dozens of ubiquitination sites, MS-based proteomics has evolved to enable system-wide ubiquitinome profiling, permitting researchers to decode the ubiquitin code on a proteome-wide scale [35]. This technical guide examines the methodological breakthroughs in MS-based ubiquitinomics, detailing how these advances have illuminated UPS biology and accelerated drug discovery efforts targeting this crucial regulatory system.

The Evolution of Mass Spectrometry Approaches in Ubiquitinomics

From Targeted Analyses to Global Profiling

Initial mass spectrometry approaches for studying ubiquitination relied heavily on tagged ubiquitin pulldown strategies, which often suffered from experimental artifacts, high background, and limited site identification [35]. The true revolution in ubiquitinomics came with the development of antibodies specifically recognizing the diglycine (K-GG) remnant left on trypsinized peptides derived from ubiquitinated proteins [35]. This innovation enabled the specific enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides from complex biological samples, dramatically increasing scalability and sensitivity.

The subsequent adoption of advanced MS acquisition techniques, particularly Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA), has addressed critical limitations of traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA). DDA's semi-stochastic sampling often led to missing values across replicate runs, reducing the number of robustly quantified ubiquitination sites in large sample series [36]. In contrast, DIA fragments all ions within predetermined isolation windows, ensuring comprehensive and reproducible data acquisition [36]. When coupled with neural network-based processing tools like DIA-NN, this approach has more than tripled ubiquitinated peptide identification compared to DDA, with single experiments now quantifying up to 70,000 ubiquitinated peptides while significantly improving robustness and quantification precision [36].

Advanced Instrumentation and Hybrid Systems

Modern mass spectrometry platforms have been instrumental in advancing ubiquitinomics. Orbitrap analyzers provide exceptionally high mass resolution (>100,000 at m/z 35,000), enabling precise mass measurements essential for distinguishing subtle modifications in complex samples [37]. Hybrid systems such as quadrupole-Orbitrap and quadrupole-time-of-flight (TOF) configurations combine the strengths of different mass analyzers, offering superior sensitivity and mass accuracy for detecting low-abundance ubiquitinated peptides [37].

Table 1: Mass Spectrometry Platforms in Ubiquitinomics

| Technology | Key Principle | Advantages for Ubiquitinomics | Typical Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orbitrap MS | Electrostatic field traps ions in orbiting motion | Ultra-high resolution and mass accuracy | Resolution >100,000 at m/z 35,000 [37] |

| Q-TOF MS | Quadrupole mass filter with time-of-flight detection | High speed and good mass accuracy | Rapid analysis of complex mixtures [37] |

| FT-ICR MS | Traps ions in magnetic field, measures cyclotron motion | Exceptional mass resolution and accuracy | Unparalleled precision for complex samples [37] |

| Ion Trap MS | Three-dimensional electric field traps ions | Capability for multi-stage MS (MSn) | Detailed structural information [37] |

Current Methodological Standards in Ubiquitinomics

Optimized Sample Preparation Protocols

Robust ubiquitinome profiling begins with optimized sample preparation. Recent innovations have introduced sodium deoxycholate (SDC)-based lysis protocols that significantly improve ubiquitin site coverage compared to traditional urea-based methods [36]. When supplemented with chloroacetamide (CAA) and immediate sample boiling, this approach rapidly inactivates cysteine ubiquitin proteases, preserving the native ubiquitination state while avoiding artifacts like di-carbamidomethylation of lysine residues that can mimic K-GG remnants [36]. This SDC-based method yields approximately 38% more K-GG peptides than urea buffer without compromising enrichment specificity [36].

Critical to accurate ubiquitinome interpretation is the parallel analysis of matched proteomes, which enables researchers to distinguish true changes in ubiquitination from alterations in underlying protein abundance [36] [35]. This is particularly important for discriminating regulatory ubiquitination events from those leading to protein degradation, as only a small fraction of proteins with increased ubiquitination actually undergo degradation [36].

Enrichment Strategies and Analytical Workflows

The core ubiquitinomics workflow involves several critical steps: (1) efficient protein extraction using denaturing conditions to preserve modifications; (2) tryptic digestion generating K-GG remnant peptides; (3) immunoaffinity enrichment using K-GG specific antibodies; and (4) liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry [36] [38]. For quantitative analyses, isobaric labeling approaches like tandem mass tagging (TMT) enable multiplexed comparisons of up to 11 conditions, significantly reducing sample requirements and instrument time [35].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Ubiquitinomics Methods

| Method | Typical Ubiquitination Sites Identified | Quantitative Precision | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDA with K-GG Antibody | ~20,000 sites [36] | Moderate (CV ~20%) [36] | Moderate | Targeted studies, validation [35] |

| DIA with K-GG Antibody | ~70,000 sites in single runs [36] | High (median CV ~10%) [36] | High | Large-scale dynamic studies [36] |

| UbiSite (LysC-based) | ~30,000 sites per replicate [35] | High specificity | Lower | Alternative enrichment strategy [35] |

| TMT Multiplexing | ~10,000+ sites [35] | High for relative quantification | Very High | Time-course studies, multiple conditions [35] |

Diagram 1: Ubiquitinomics Experimental Workflow. This diagram illustrates the core steps in mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinome profiling, highlighting key methodological decision points between DDA and DIA acquisition strategies.

Applications in Basic Research and Drug Discovery

Decoding Biological Signaling Networks

The application of advanced ubiquitinomics has revealed unprecedented insights into cellular signaling networks. A landmark study employing time-resolved ubiquitinome profiling following inhibition of the deubiquitinase USP7 demonstrated the power of this approach to dissect the scope and kinetics of DUB activity on a proteome-wide scale [36]. This research quantified ubiquitination changes on hundreds of proteins within minutes of USP7 inhibition, yet revealed that only a small fraction of these ubiquitination events led to protein degradation, highlighting the predominance of regulatory ubiquitination in USP7 function [36].

Ubiquitinomics has also illuminated the complex interplay between ubiquitination and other post-translational modifications. Sequential pulldown approaches now enable the analysis of multiple "PTMomes" (phosphoproteome, acetylome, ubiquitinome) from the same sample, revealing how these modifications act in concert to coordinate cellular events [35]. This multi-PTM profiling provides a more integrated view of cellular signaling networks and their perturbation in disease states.

Accelerating Targeted Protein Degradation Therapeutics

The UPS has emerged as a particularly promising arena for drug discovery, with MS-based ubiquitinomics playing a crucial role in characterizing mechanisms of action for emerging therapeutic modalities. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and other targeted protein degradation approaches leverage the ubiquitin system to direct specific proteins for destruction, and ubiquitinomics provides essential tools for validating target engagement and understanding resistance mechanisms [22].

Ubiquitinome profiling enables rapid mode-of-action studies for candidate drugs targeting DUBs or ubiquitin ligases with high precision and throughput [36]. This application is particularly valuable in early drug discovery, where understanding the specificity and off-target effects of UPS-targeting compounds can guide lead optimization and reduce late-stage attrition. Multiple components of the UPS are already validated drug targets, with proteasome inhibitors clinically approved for hematological malignancies and E3 ligase modulators showing promise for degrading otherwise "undruggable" proteins [36].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitinomics

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-GG Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides | High specificity for diglycine remnant; commercial availability (Cell Signaling Technology) | Exhibits bias for certain amino acid contexts [35] |

| SDC Lysis Buffer | Protein extraction with protease inhibition | Immediate boiling with CAA inactivates DUBs; 38% improved yield vs urea [36] | Avoids di-carbamidomethylation artifacts [36] |

| DIA-NN Software | Neural network-based DIA data processing | Specialized scoring for modified peptides; library-free analysis capability | Enables >70,000 ubiquitinated peptide IDs [36] |

| TMT Multiplexing | Isobaric labeling for quantitative comparisons | Allows 11-plex experiments; reduced sample requirements | UbiFast method labels peptides on-bead after enrichment [35] |

| UbiSite Antibody | Recognition of LysC ubiquitin fragments | Alternative to K-GG antibody; different sequence bias | Identified ~64,000 sites with proteasome inhibition [35] |

The Ubiquitin Signaling Network: Complexity and Function

Diagram 2: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Signaling Network. This diagram illustrates the enzymatic cascade governing protein ubiquitination and the diverse functional outcomes determined by ubiquitin chain topology.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

As mass spectrometry technologies continue to advance, several emerging trends promise to further transform ubiquitinomics research. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with spectral interpretation is already enhancing identification confidence and quantification accuracy, particularly for modified peptides [36]. Single-cell ubiquitinomics represents another frontier, though significant technical hurdles remain in achieving sufficient sensitivity for low-abundance ubiquitination events at the single-cell level [37].

The growing appreciation of ubiquitination's diversity—including non-canonical ubiquitination on cysteine, serine, threonine, and protein N-termini, as well as the complex landscape of ubiquitin chain branching and mixed linkages—presents both challenges and opportunities for methodological development [34]. Future ubiquitinomics approaches will need to address this complexity more comprehensively, moving beyond K-GG-centric analyses to capture the full spectrum of ubiquitin modifications.

Mass spectrometry has fundamentally transformed our ability to decipher the ubiquitin code, progressing from isolated observations to system-wide profiling of ubiquitination dynamics. This transformation has not only illuminated basic mechanisms of ubiquitin signaling but also created new avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other pathologies linked to UPS dysregulation. As ubiquitinomics methodologies continue to evolve in sensitivity, throughput, and comprehensiveness, they will undoubtedly uncover new layers of complexity in ubiquitin signaling and accelerate the development of novel UPS-targeting therapeutics.