HECT vs. RING E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of HECT and RING E3 ubiquitin ligases, the key enzymes conferring specificity in the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

HECT vs. RING E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of HECT and RING E3 ubiquitin ligases, the key enzymes conferring specificity in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. We delve into their distinct catalytic mechanisms, structural classifications, and regulatory principles. The content explores advanced methodologies for studying these ligases and the burgeoning field of their therapeutic inhibition, highlighting recent breakthroughs in allosteric drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes foundational knowledge with current applications to inform the development of novel targeted therapies for cancer, neurological disorders, and metabolic diseases.

Core Mechanisms and Structural Families of HECT and RING E3 Ligases

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that directs myriad eukaryotic proteins to various fates and functions, with its most recognized role being the targeting of proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome [1]. This modification involves the sequential action of a three-enzyme cascade: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3) [1]. The process begins with E1 activating ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, forming a high-energy thioester bond. The ubiquitin is then transferred to the active-site cysteine of an E2 enzyme. Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the target substrate [1] [2]. With only two E1s, approximately 40 E2s, and over 600 E3s encoded in the mammalian genome, the E3 ligases are primarily responsible for the exquisite spatial, temporal, and substrate specificity that characterizes the ubiquitination process [1] [3]. This review will objectively compare the mechanisms and experimental approaches for studying the two major classes of E3 ligases: HECT and RING types, providing researchers with a comprehensive guide to their distinct functionalities.

E3 Ligase Families: Architectural and Mechanistic Diversity

E3 ubiquitin ligases are primarily categorized into three major families based on their structural features and catalytic mechanisms: RING (Really Interesting New Gene), HECT (Homologous to E6AP C-Terminus), and RBR (RING-between-RING) [4] [5]. The RING family is the largest, comprising over 600 members in humans, while the HECT family includes approximately 28 members, and the RBR family about 14 members [4]. A fourth group, the multi-subunit RING E3s exemplified by Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), represents some of the most complex arrangements in this system [1] [6].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major E3 Ligase Families

| Feature | RING-type E3s | HECT-type E3s | RBR-type E3s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Family Size | ~600 members [4] [7] | ~28 members [2] [4] | ~14 members [8] [4] |

| Catalytic Mechanism | Direct transfer from E2 to substrate [3] | Two-step mechanism with E3-Ub thioester intermediate [1] [4] | RING/HECT hybrid mechanism [8] [9] |

| Intermediate Formation | No E3-Ub intermediate [3] | Obligate E3-Ub thioester intermediate [1] [2] | E3-Ub thioester intermediate [8] |

| Structural Features | Zn²⁺-coordinating RING domain [1] | Bilobed HECT domain (N-lobe, C-lobe) [1] [2] | RING1-IBR-RING2 domain organization [8] |

| Representative Examples | Cbl, MDM2, APC/C, SCF [1] | NEDD4, E6AP, HUWE1, SMURFs [1] [2] | Parkin, HOIP, HHARI [8] [9] |

RING-type E3 Ligases: Scaffolds for Direct Transfer

RING-type E3s constitute the largest class of ubiquitin ligases, characterized by a canonical RING finger domain that coordinates two zinc ions in a "cross-brace" structure [1] [7]. Unlike HECT E3s, RING finger domains do not form a catalytic intermediate with ubiquitin. Instead, they serve as scaffolds that bring E2 and substrate into close proximity, with evidence suggesting they can also allosterically activate E2s [1]. RING E3s can function as monomers, dimers (both homo- and heterodimers), or multi-subunit complexes such as the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) [1] [3]. The CRL family represents particularly complex structures that utilize a wide variety of substrate receptors, adapter proteins, and cooperating ligases [6].

HECT-type E3 Ligases: Two-Step Catalytic Enzymes

HECT E3s are defined by a conserved C-terminal HECT domain approximately 350 amino acids in length, consisting of an N-lobe that interacts with the E2 and a C-lobe containing the active-site cysteine that forms a thioester bond with ubiquitin [1] [2] [4]. These two lobes are connected by a flexible hinge region that allows them to come together during ubiquitin transfer [1]. The N-terminal regions of HECT E3s are diverse and mediate substrate targeting [1]. Based on their N-terminal domain organization, the 28 human HECT E3s are divided into three subfamilies: the NEDD4 family (9 members) characterized by C2 and WW domains; the HERC family (6 members) featuring RCC1-like domains (RLD); and "other" HECT E3s (13 members) with varied N-terminal domains [2] [4].

RBR-type E3 Ligases: Hybrid Mechanisms

RBR E3 ligases represent a unique hybrid category that functions with characteristics of both RING and HECT-type mechanisms [8] [9]. These enzymes contain three zinc-binding domains termed RING1, in-between RING (IBR), and RING2, collectively called the RBR module [8]. Similar to RING E3s, the RING1 domain binds the E2~Ub conjugate. However, like HECT E3s, they then catalyze ubiquitin transfer via a catalytic cysteine in the RING2 domain, forming a thioester intermediate [8] [9]. Parkin, one of the most studied RBR E3s, requires phosphorylation for activation and contains four RING domains coordinating eight zinc molecules [9].

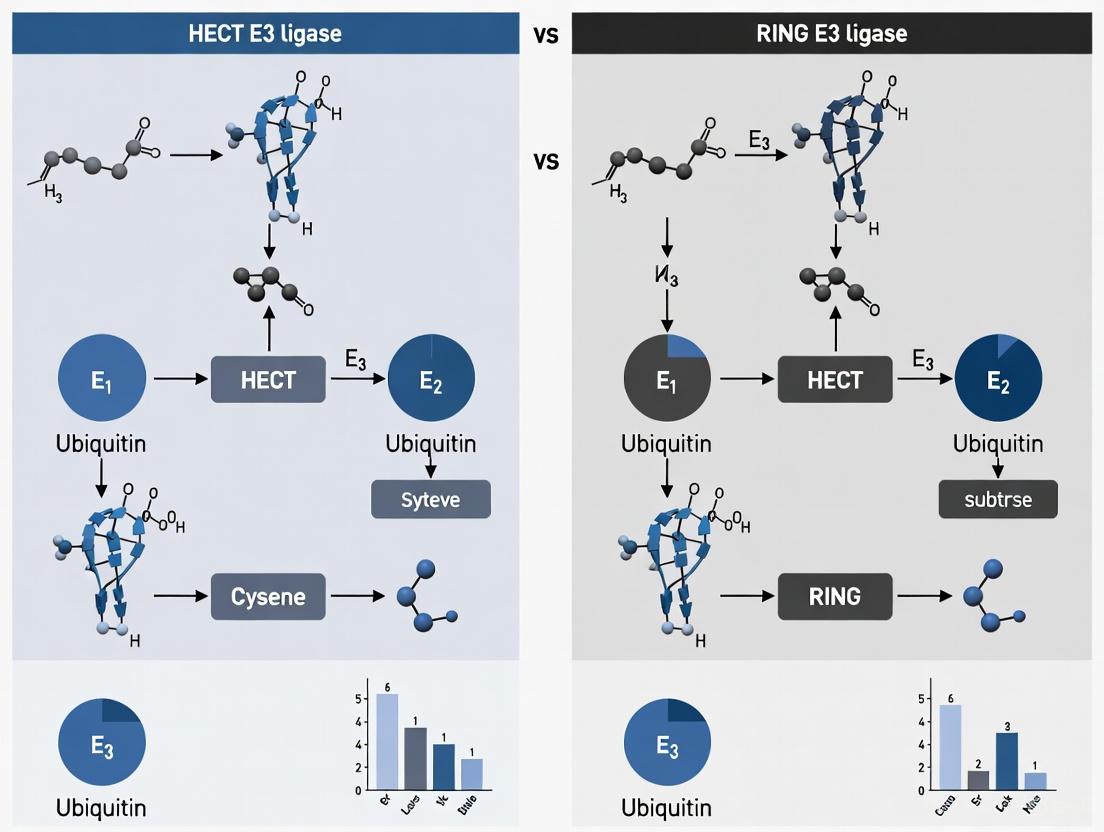

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination cascade comparing direct RING-type and two-step HECT-type mechanisms. HECT E3s form a catalytic intermediate, while RING E3s facilitate direct transfer.

Comparative Catalytic Mechanisms: HECT versus RING

Fundamental Mechanistic Differences

The most significant distinction between HECT and RING E3 ligases lies in their catalytic mechanisms. RING E3s function as allosteric activators of the E2 and scaffolds that bring the E2 in close proximity to the substrate, enabling direct ubiquitin transfer from the E2 to the substrate without forming an E3-Ub intermediate [3] [7]. In contrast, HECT E3s catalyze ubiquitination in a two-step reaction: first, they accept the activated ubiquitin from the E2 in a transthiolation reaction onto their catalytic cysteine, forming a HECT-Ub thioester intermediate; subsequently, the ubiquitin moiety is transferred to a lysine on the target substrate [1] [4].

Structural studies of the NEDD4L HECT domain in complex with ubiquitin-conjugated E2 revealed that the C-lobe contacts the esterified ubiquitin and folds down onto UbcH5B, reducing the distance between the E2 and E3 catalytic cysteines to approximately 8Å [1]. This contrasts with the more open architecture observed in E6AP complexes, where the catalytic cysteine residues are 41Å apart, suggesting that the two lobes of the HECT domain are connected through a flexible hinge that allows them to come together during ubiquitin transfer [1].

Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Specificity

Another crucial distinction between these E3 families lies in their ability to generate specific polyubiquitin chain linkages, which determine the functional consequences for the modified substrate. HECT E3s appear to possess intrinsic linkage specificity dictated by structural elements within their catalytic domains [4]. For instance, NEDD4 family members primarily synthesize K63-linked chains, while E6AP is a K48-specific enzyme, and HUWE1 generates K6-, K11-, and K48-linked polyubiquitin chains [4]. For NEDD4 enzymes, the presence of a non-covalent ubiquitin-binding site (Ub exosite) in the N-lobe appears to be required for enzyme processivity, possibly by stabilizing and orienting the distal end of growing ubiquitin chains on the substrate [4].

RING E3s, conversely, typically derive their linkage specificity from their partnered E2 enzymes, though some RING E3s can influence chain topology through additional mechanisms [1]. The cullin-RING ligase (CRL) superfamily represents particularly sophisticated examples, with complexes like the SCF (Skp1-Cullin-F-box) utilizing various substrate receptors to achieve specificity [1].

Table 2: Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Specificity and Functional Consequences

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Representative E3 Ligases |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [3] | E6AP (HECT) [4] |

| K63-linked | Signaling, DNA repair, endocytosis [3] | NEDD4 family (HECT) [4] |

| K11-linked | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation [2] [3] | APC/C (RING) [2], HUWE1 (HECT) [4] |

| K6-linked | DNA damage response, mitochondrial signaling [2] [3] | HUWE1 (HECT) [2] |

| K27-linked | DNA damage response [2] [3] | RNF168 (RING) [2] |

| K29-linked | Negatively regulates Wnt signaling [2] | Cbl-b, Itch (RING/HECT) [2] |

| K33-linked | T-cell receptor regulation, intracellular trafficking [2] [3] | Cbl-b, Itch (RING/HECT) [2] |

| M1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB signaling, immunity, inflammation [2] [3] | LUBAC complex (RBR) [2] [8] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying E3 Mechanisms

E2-Ub Discharge Assays for Catalytic Activity

E2-Ub thioester discharge assays represent a fundamental method for investigating the catalytic activity of E3 ligases, particularly useful for distinguishing between RING and HECT mechanisms [8]. In this assay, the E2 is loaded with ubiquitin to form a thioester conjugate (E2~Ub), which is then incubated with the E3 ligase of interest. The discharge of ubiquitin from the E2 is monitored over time, typically using non-reducing SDS-PAGE to preserve thioester linkages [8].

For HECT E3s, this assay demonstrates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the catalytic cysteine of the HECT domain, forming the HECT-Ub intermediate. For RING E3s, the assay shows enhanced discharge rates due to the allosteric activation of the E2's catalytic activity. This method has been particularly valuable for studying RBR E3s like HOIL-1 and RNF216, which display poor E2-Ub discharge activity in the absence of allosteric activators but show strongly enhanced activity in the presence of specific di-ubiquitin species (M1- or K63-linked for HOIL-1; K63-linked for RNF216) [8].

Protocol Summary:

- Prepare E2~Ub thioester by incubating E2 with E1, ubiquitin, and ATP

- Purify E2~Ub conjugate using rapid gel filtration or acid quenching

- Incubate E2~Ub with E3 ligase in reaction buffer

- Stop reactions at time points using non-reducing SDS sample buffer

- Analyze by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies

- Quantify E2~Ub discharge kinetics using densitometry

BioE3 System for Substrate Identification

The BioE3 system represents an innovative technological approach for identifying specific substrates of E3 ligases, addressing the significant challenge of distinguishing genuine targets from mere interactors [5]. This method combines site-specific biotinylation of ubiquitin-modified substrates with BirA-E3 ligase fusion proteins under optimized conditions to enable proteomic identification of E3-specific targets [5].

The key innovation in BioE3 involves using an AviTag variant with lower affinity for BirA (bioGEF instead of bioWHE) to enable proximity-dependent labeling specifically at sites where the E3 is actively ubiquitinating substrates. This system has been successfully applied to both RING-type E3s (RNF4, MIB1, MARCH5, RNF214) and HECT-type E3s (NEDD4), identifying both known and novel targets [5].

Protocol Summary:

- Generate stable cell line expressing inducible bioGEF-Ub (AviTag with GEF mutation)

- Culture cells in biotin-depleted media prior to experiments

- Introduce BirA-E3 fusion construct into bioGEF-Ub cells

- Induce bioGEF-Ub and BirA-E3 expression with doxycycline

- Add exogenous biotin for time-limited, proximity-dependent labeling

- Harvest cells and perform streptavidin capture of biotinylated substrates

- Identify substrates by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

Diagram 2: BioE3 experimental workflow for identifying E3 ligase substrates using proximity-dependent biotinylation and streptavidin capture.

Structural Biology Approaches

Structural studies have been instrumental in elucidating the distinct mechanisms of HECT and RING E3 ligases. X-ray crystallography of the NEDD4 HECT domain in complex with ubiquitin-conjugated E2 provided the first structural insights into a Ub-loaded E3, revealing how the donor ubiquitin is bound to the Nedd4 C-lobe with its C-terminal tail locked in an extended conformation, primed for catalysis [10]. Similarly, high-resolution (1.58 Å) crystal structures of Parkin-R0RBR have revealed the fold architecture for the four RING domains of this RBR E3 and several unpredicted interfaces that regulate its activity [9].

More recently, cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) has revealed a wide variety of structures in the CRL family, suggesting how ubiquitin transfer occurs in these multi-subunit complexes [6]. When combined with hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDXMS), these approaches have expanded our understanding of how covalent NEDD8 modification (neddylation) activates CRLs, particularly by facilitating cooperation with additional RING-between-RING ligases to transfer ubiquitin [6].

Research Reagent Solutions for E3 Ligase Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for E3 Ligase Mechanistic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Activity Probes | Ubiquitin-vinyl sulfone (Ub-VS) [9] | Covalent labeling of active site cysteines in HECT and RBR E3s |

| Stable Cell Lines | TRIPZ-bioGEFUbnc cells [5] | Inducible expression of biotinylatable ubiquitin for BioE3 studies |

| E3 Fusion Constructs | BirA-E3 fusions (BirA-RNF4, BirA-MIB1) [5] | Proximity-dependent biotinylation in BioE3 system |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | Ubnc (L73P) [5], bioGEF-Ub [5] | Preventing deubiquitination; enabling specific biotinylation |

| Chain-Linkage Specific Reagents | M1-, K63-, K48-linked di-ubiquitin [8] | Studying allosteric activation and linkage specificity |

| Structural Biology Tools | Catalytic cysteine mutants (Cys to Ala) [8] | Trapping intermediates for structural studies |

| E2 Conjugates | UbcH7(C86K)-Ub [8] | Stable E2-Ub conjugate for binding studies |

The distinct mechanistic properties of HECT and RING E3 ligases have significant implications for both basic research and therapeutic development. From a research perspective, the choice between studying HECT versus RING E3s often depends on the biological context and specific research questions. HECT E3s, with their defined two-step mechanism and intrinsic linkage specificity, offer more straightforward systems for enzymological studies and substrate identification using methods like BioE3 [5]. Their well-characterized domain structure also facilitates structural studies, as demonstrated by the multiple HECT domain structures solved over the past decade [1] [10].

RING E3s, representing the majority of ubiquitin ligases, present both challenges and opportunities due to their diversity and complex regulation. The multi-subunit nature of many RING E3 complexes like CRLs requires more sophisticated experimental approaches, often combining cryoEM with biochemical techniques [6]. However, their central role in numerous signaling pathways makes them particularly relevant for physiological and pathological studies.

From a therapeutic perspective, both E3 classes represent attractive drug targets. The catalytic cysteine in HECT and RBR E3s offers a potential site for covalent inhibitors, while the protein-protein interactions in RING E3s provide opportunities for small-molecule intervention [3]. Understanding the distinct mechanisms of these E3 families continues to drive innovations in targeted protein degradation, including PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) that often utilize E3 ligases for directing specific proteins to the proteasome [3].

As research technologies advance, particularly in structural biology and proteomics, our understanding of the nuances between different E3 mechanisms continues to deepen. The development of techniques like BioE3 that can be applied across multiple E3 families promises to accelerate substrate identification and mechanistic studies, potentially revealing new therapeutic opportunities for manipulating the ubiquitin-proteasome system in disease contexts.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that directs protein fate, influencing stability, activity, and localization. Central to this process are E3 ubiquitin ligases, which confer substrate specificity. Among these, the Homologous to the E6AP C-Terminus (HECT) family represents a distinct class characterized by a unique catalytic mechanism involving a direct thioester intermediate. This guide provides a detailed comparison of HECT ligase catalysis against other major E3 ligase families, focusing on mechanistic insights, experimental data, and methodological approaches relevant to ongoing research and therapeutic development.

Comparative Mechanisms of Major E3 Ligase Families

E3 ubiquitin ligases are categorized based on their structural domains and catalytic mechanisms. The table below contrasts the core features of the three major families.

Table 1: Core Mechanistic Features of E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families

| Feature | HECT Ligases | RING Ligases | RBR Ligases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Mechanism | Two-step with covalent E3~Ub intermediate [1] [11] | One-step, direct transfer from E2 to substrate [1] [8] | Hybrid RING/HECT two-step mechanism [8] |

| Intermediate | Thioester-linked HECT~Ub complex [12] [11] | No stable E3-Ub intermediate [1] | Thioester-linked RING2~Ub complex [8] |

| Role of E3 | Catalytic (forms chemical bond with Ub) [11] | Scaffold (brings E2 and substrate together) [1] [13] | Hybrid (RING1 as scaffold, RING2 as catalytic) [8] |

| Ubiquitin Transfer | From E2 to E3 (transthiolation), then to substrate (aminolysis) [11] | Directly from E2~Ub to substrate [1] | From E2 to RING2 (transthiolation), then to substrate (aminolysis) [8] |

Diagram 1: HECT vs. RING catalytic mechanisms. HECT ligases form a covalent thioester intermediate, while RING ligases facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer.

The HECT Ligase Catalytic Cycle: A Detailed Look

The HECT domain, a ~350-amino-acid C-terminal region, defines this family and is structurally organized into two lobes. The N-lobe binds the E2~Ub conjugate, while the C-lobe contains the active-site cysteine that forms the thioester bond with ubiquitin [1] [11]. The catalytic cycle proceeds via two well-defined steps:

- Transthiolation: The ubiquitin is transferred from the active-site cysteine of the E2 enzyme to the active-site cysteine within the HECT C-lobe, forming a transient, high-energy HECT~ubiquitin thioester intermediate [11] [14].

- Aminolysis: The ubiquitin is then ligated from the HECT enzyme to a primary amino group (typically the ε-amino group of a lysine) on the target substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [11].

A key feature of the HECT domain is the flexible hinge that connects the N and C lobes. Early structural studies suggested that large conformational changes of the C-lobe are required to bring the thioester bond within proximity of the substrate lysine [1] [15]. Recent studies on NEDD4-2 propose a proximal indexation mechanism requiring oligomerization. This model involves two functionally distinct E2~Ub binding sites: an initial site for HECT~Ub thioester formation and a canonical site for polyubiquitin chain elongation, which functions in trans across adjacent subunits of the oligomer [12].

Key Experimental Data and Methodologies

Understanding the HECT mechanism relies on specific biochemical and biophysical assays. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings and the experimental approaches used to obtain them.

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings in HECT Ligase Catalysis

| Experimental Observation | Quantitative Data | Experimental Method | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligomerization for Full Activity | Trimeric active form; F823A mutation decreases kcat by ≥10^4-fold [12] | Gel filtration chromatography; Dynamic light scattering; Site-directed mutagenesis [12] | Demonstrates that polyubiquitin chain assembly, but not monoubiquitination, requires oligomerization [12] |

| Two Distinct E2~Ub Binding Sites | Km for Ubc5B~Ub is 8 ± 2 nM (without substrate) vs. 127 ± 49 nM (with substrate) [14] | Initial velocity enzyme kinetics under E3-limiting conditions; Use of E2 mutant proteins (T98A, F62A) [14] | Functional uncoupling of thioester formation (Site 1) from chain elongation (Site 2) [12] [14] |

| Linkage Specificity | NEDD4-2 assembles Lys-63-linked polyubiquitin chains [12] [14] | In vitro ubiquitination assays with wild-type and mutant ubiquitin (e.g., K48R, K63R) [14] | Clarifies chain linkage and fate of substrate (often endocytic trafficking vs. proteasomal degradation) |

| Inhibition of Oligomerization | N-acetylphenylalanyl-amide acts as noncompetitive inhibitor (Ki = 8 ± 1.2 mM) [12] | Kinetic assays with small-molecule Phe-823 mimics [12] | Suggests a therapeutic strategy for targeting HECT ligases by disrupting the active oligomer |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Polyubiquitin Chain Assembly Assay

A foundational assay for studying HECT ligase mechanism involves measuring the formation of unanchored polyubiquitin chains in the absence of a protein substrate [14]. Below is a generalized protocol derived from these studies.

Objective: To quantify the rate of polyubiquitin chain formation catalyzed by a HECT E3 ligase.

Reagents:

- Purified Proteins: HECT E3 ligase (e.g., full-length NEDD4-2), E1 activating enzyme, E2 conjugating enzyme (e.g., UbcH5B/UBE2D1), Ubiquitin.

- Radioisotope: ¹²⁵I-labeled ubiquitin.

- Reaction Buffer: Typically containing Tris-HCl (pH ~7.5), MgCl₂, ATP, DTT, and an ATP-regenerating system (e.g., Creatine Phosphate and Creatine Kinase).

- Quenching Solution: SDS-PAGE loading buffer with β-mercaptoethanol.

- Equipment: Water bath or thermomixer, gel electrophoresis apparatus, phosphorimager or X-ray film.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: On ice, prepare a master mix containing reaction buffer, ATP, ATP-regenerating system, E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme, unlabeled ubiquitin, and ¹²⁵I-ubiquitin. The E3 ligase is often omitted at this stage.

- Initiation: Pre-incubate the master mix at 30°C for 1-2 minutes to allow E1-mediated charging of the E2 enzyme. Start the reaction by adding the HECT E3 ligase.

- Time Course: At defined time intervals (e.g., 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 minutes), remove an aliquot of the reaction and mix it with an equal volume of quenching solution to denature the proteins and stop the reaction.

- Analysis: Resolve the quenched samples by SDS-PAGE. Visualize and quantify the formation of high molecular weight polyubiquitin chains using autoradiography and a phosphorimager.

Key Applications:

- Determining kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) for E2~Ub conjugates.

- Testing the functional impact of mutations in the HECT domain (e.g., active-site cysteine, oligomerization interface).

- Investigating linkage specificity by using ubiquitin mutants where specific lysines are mutated to arginine.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists critical reagents and tools used in mechanistic studies of HECT ligases.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HECT Ligase Research

| Research Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Stable E2~Ub Conjugates | Engineered oxyester (e.g., E2 C85S~Ub) or isopeptide (e.g., E2 C86K~Ub) mimics of the labile thioester [12] [8]. | Trapping catalytic intermediates for structural studies (e.g., X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM) [16]. |

| Active-Site Mutants | Mutation of the catalytic cysteine to serine or alanine (e.g., C922A in NEDD4-2) [12]. | Used as catalytically dead controls or to trap the HECT~Ub intermediate for structural analysis. |

| Oligomerization-Disrupting Mutants | Mutation of conserved hydrophobic residues at the subunit interface (e.g., F823A in NEDD4-2) [12]. | Functionally uncouples monoubiquitination from polyubiquitin chain assembly. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Mutants | Ubiquitin where a single lysine is mutated to arginine (e.g., Ub K48R, Ub K63R) [16] [14]. | Determines the linkage type of polyubiquitin chains synthesized by the HECT ligase. |

| Chemical Probes (e.g., triUb~probe) | Synthetic, chemically cross-linked ubiquitin probes that mimic transition states or branched chains [16]. | Trapping and visualizing transient enzymatic states, such as during branched ubiquitin chain formation. |

Advanced Concepts: Branched Ubiquitination and Oligomerization

Recent research has expanded our understanding of HECT ligase function beyond simple chain elongation. For instance, the HECT E3 Ufd4 preferentially catalyzes the formation of K29/K48-branched polyubiquitin chains on pre-assembled K48-linked ubiquitin chains, which acts as an enhanced degradation signal [16]. Structural visualization using cryo-EM has revealed how the N-terminal domains and HECT C-lobe of Ufd4 work together to recruit the substrate ubiquitin chain and orient the acceptor lysine for catalysis [16].

Furthermore, the requirement for oligomerization, specifically trimerization, has been established for full-length HECT ligases like NEDD4-2 and E6AP [12]. This quaternary structure is essential for the proximal indexation mechanism, where the two distinct E2-binding sites are located on different subunits of the trimer, enabling efficient polyubiquitin chain elongation in trans [12].

Diagram 2: Oligomerization in HECT catalysis. The active trimeric form allows one subunit charged with ubiquitin (HECT~Ub) to interact with an E2~Ub bound to a second subunit, facilitating efficient polyubiquitin chain assembly.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system is a fundamental regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells, controlling protein degradation and influencing virtually all cellular processes. Within this system, E3 ubiquitin ligases serve as the critical specificity determinants, responsible for recognizing substrate proteins and facilitating their tagging with ubiquitin. Among the several families of E3 ligases, the RING (Really Interesting New Gene) family represents the largest and most diverse group, with over 600 members in the human genome. RING-type E3 ligases function as scaffold proteins that mediate the direct transfer of ubiquitin from an E2 conjugating enzyme to a substrate protein, without forming a covalent intermediate. This direct transfer mechanism distinguishes RING E3s from HECT-type E3s, which utilize a two-step catalytic process involving a transient E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate. Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms of RING ligase catalysis provides fundamental insights into cellular regulation and offers potential therapeutic avenues for numerous diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune dysfunction [17] [18] [19].

The RING domain itself is characterized by a conserved cross-braced zinc-binding structure that coordinates two zinc ions through a specific arrangement of cysteine and histidine residues. This structural motif creates a stable platform for binding E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes that have been charged with ubiquitin. RING E3s function as multimers—either homodimers or heterodimers—with the RING domains positioned such that their E2-binding surfaces face away from each other, suggesting that cooperative interactions between RING-bound E2s are unlikely in the context of a dimer. Instead, this arrangement likely facilitates the recruitment of multiple E2s for processive ubiquitination or the ubiquitination of complex substrates [17].

Core Catalytic Mechanism of RING E3 Ligases

The Scaffold Function and E2∼Ub Recruitment

RING E3 ligases function primarily as molecular scaffolds that physically bridge E2∼Ub conjugates with substrate proteins. Unlike HECT E3s, RING ligases do not form a covalent thioester intermediate with ubiquitin during the catalytic cycle. Instead, they facilitate the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 active site cysteine to a lysine residue on the substrate protein. This fundamental mechanistic distinction has profound implications for the regulation and biological functions of these two E3 families [17] [19].

The catalytic cycle begins with the RING domain recruiting an E2 enzyme that has been charged with ubiquitin (E2∼Ub). Structural studies have revealed that RING domains bind to the N-terminal helix of the ubiquitin-conjugating (UBC) fold of E2s. Notably, the affinity of RING E3s for E2∼Ub is significantly enhanced compared to E2 alone, due to additional interactions between the RING domain and the donor ubiquitin (UbD) within the ternary complex. This enhanced binding affinity contributes to the catalytic efficiency of ubiquitin transfer [20].

Induction of the Closed E2∼Ub Conformation

A critical function of RING E3 ligases in catalysis is their ability to stabilize a closed conformation of the E2∼Ub conjugate. In the absence of a RING E3, E2∼Ub conjugates predominantly exist in an "open" conformation, where ubiquitin is dynamically associated with the E2 surface. Upon RING binding, the E2∼Ub conjugate is repositioned into a closed conformation, where ubiquitin's C-terminal tail is optimally positioned for nucleophilic attack by the substrate lysine. This conformational change activates the thioester bond for transfer and precisely orients the reactive groups for catalysis [20].

The transition from open to closed conformation brings the ubiquitin C-terminus in close proximity to the substrate-binding site, effectively measuring the distance between the E2 active site and the target lysine on the substrate. This spatial coordination ensures the specificity and efficiency of ubiquitin transfer. The closed conformation is characterized by extensive contacts between the RING domain and both the E2 and ubiquitin moieties, creating a stable catalytic complex primed for ubiquitin transfer [20].

Table 1: Key Structural Elements in RING E3 Catalytic Mechanism

| Structural Element | Function in Catalysis | Consequence of Disruption |

|---|---|---|

| RING Domain | Binds E2∼Ub conjugate and stabilizes closed conformation | Abolished ubiquitin transfer |

| Linchpin Residue | Forms hydrogen bonds with UbD and E2 to stabilize closed state | Reduced E3 activity, impaired ubiquitination |

| Zinc-Binding Sites | Maintains structural integrity of RING domain | Loss of E2 binding capacity |

| Dimerization Interface | Enables formation of active E3 complex | Altered substrate specificity, reduced processivity |

The Linchpin Residue and Ubiquitin Transfer

Central to the RING E3 mechanism is a conserved cationic "linchpin" residue (most commonly an arginine) that plays a crucial role in stabilizing the closed E2∼Ub conformation. Structural analyses of multiple RING/E2∼Ub complexes reveal that this linchpin residue is positioned at the interface between the donor ubiquitin and the E2 enzyme, where it forms a network of hydrogen bonds with both partners. This interaction stabilizes the catalytically competent conformation and enhances the efficiency of ubiquitin transfer [20].

Recent research using the model RING E3 RNF38 has demonstrated that substitution of the linchpin arginine with other amino acids modulates ubiquitination efficiency, ranging from minor reduction to complete abolition of activity. Interestingly, the identity of the linchpin residue influences E2∼Ub binding but does not directly correlate with E3 activity, suggesting that the linchpin's primary role is in stabilizing the proper E2∼Ub conformation rather than simply increasing binding affinity. NMR and X-ray crystallography analyses reveal that different linchpin residues stabilize E2∼Ub in the catalytically competent conformation to varying degrees, with arginine being the most effective [20].

The importance of the linchpin residue extends beyond a single E3, as demonstrated by experiments with XIAP, where a Y485R substitution in the linchpin position enhanced E2∼Ub stabilization and increased substrate ubiquitination in cells. This conservation of function across different RING E3s highlights the fundamental nature of this mechanistic feature in RING-mediated ubiquitination [20].

Figure 1: RING E3 Catalytic Cycle - RING E3 ligases facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer from E2∼Ub to substrates without forming covalent E3-ubiquitin intermediates.

Comparative Analysis: RING vs. HECT E3 Ligase Mechanisms

Fundamental Mechanistic Differences

The catalytic mechanisms of RING and HECT E3 ligases differ fundamentally in their use of covalent intermediates. While RING E3s function as pure scaffolds, HECT E3s employ a two-step mechanism involving a covalent E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate. In HECT E3s, ubiquitin is first transferred from the E2 to a catalytic cysteine residue within the HECT domain, forming a HECT∼Ub intermediate. Subsequently, the ubiquitin is transferred from the HECT E3 to the substrate lysine residue. This two-step mechanism provides HECT E3s with greater direct control over the ubiquitination process but may also render them more susceptible to regulatory checkpoints [21] [11].

The structural organization of HECT domains reflects this two-step mechanism. HECT domains consist of an N-lobe that binds the E2 and a C-lobe containing the active site cysteine, connected by a flexible hinge region. Recent structural studies of HECT E3s like Ufd4 and Rsp5 have revealed that the catalytic architecture involves three-way interactions between ubiquitin and both lobes of the HECT domain, which orient the E3∼Ub thioester bond for ligation and restrict the location of the substrate-binding domain to prioritize target lysines for ubiquitination [16] [11].

Table 2: Comparative Mechanisms of RING vs. HECT E3 Ligases

| Feature | RING E3 Ligases | HECT E3 Ligases |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Mechanism | Direct transfer from E2 to substrate | Two-step mechanism with E3-Ub intermediate |

| Covalent Intermediate | No | Yes (thioester-linked HECT∼Ub) |

| Primary Function | Molecular scaffold | Catalytic enzyme |

| Ubiquitin Chain Specification | Determined by E2 with E3 influence | Primarily determined by E3 |

| Structural Domains | RING domain (zinc-coordinating) | HECT domain (N-lobe, C-lobe with catalytic Cys) |

| Regulatory Mechanisms | Allosteric activation, dimerization, post-translational modifications | Allosteric inhibition, conformational changes, accessory domains |

Implications for Ubiquitin Chain Formation and Specificity

The mechanistic differences between RING and HECT E3 ligases have significant implications for their roles in determining ubiquitin chain topology. For RING E3s, the specificity of ubiquitin chain linkage is influenced by both the E2 enzyme and the E3 itself. Some E2s are dedicated to specific ubiquitin linkages, while others are more promiscuous. Thus, a given RING E3 can generate different ubiquitin linkages depending on the E2 with which it is paired. This partnership creates a layered regulatory system for controlling ubiquitin chain specificity [17].

In contrast, HECT E3s exercise more direct control over linkage specificity through their catalytic domains. For example, structural studies of the HECT E3 ligase Ufd4 have revealed how it preferentially catalyzes K29-linked ubiquitination on K48-linked ubiquitin chains to form K29/K48-branched ubiquitin chains. The N-terminal ARM region and HECT domain C-lobe of Ufd4 work together to recruit K48-linked diUb and orient Lys29 of its proximal Ub toward the active cysteine for K29-linked branched ubiquitination. This level of specificity is encoded within the HECT E3 structure itself [16].

The formation of branched ubiquitin chains represents an emerging area of complexity in ubiquitin signaling. While both RING and HECT E3s can generate branched chains, their mechanistic approaches differ. RING E3s typically require sequential action with different E2 partnerships, while HECT E3s like Ufd4 can directly assemble specific branched architectures through coordinated recognition of the acceptor chain and catalytic transfer [16].

Experimental Approaches for Studying RING E3 Mechanisms

Key Methodologies and Techniques

Understanding RING E3 ligase mechanisms has relied on a combination of structural, biochemical, and cellular approaches. X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM have been instrumental in visualizing RING/E2∼Ub complexes and understanding the structural basis of closed conformation stabilization. These techniques have revealed critical details about the linchpin residue interaction network and the overall architecture of the catalytic complex [8] [20].

Biochemical assays play a crucial role in characterizing RING E3 activity. E2∼Ub discharge assays measure the ability of RING E3s to stimulate the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to acceptor molecules. These assays can be performed under various conditions to assess the impact of mutations, allosteric effectors, or post-translational modifications on RING E3 activity. For example, discharge assays with HOIL-1 and RNF216 RBR E3 ligases (a RING-related family) demonstrated their allosteric activation by specific diubiquitin linkages (M1- and K63-linked diUb for HOIL-1; K63-linked diUb for RNF216) [8].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) provide quantitative measurements of binding affinities between RING E3s, E2∼Ub conjugates, and potential allosteric regulators. These techniques have revealed that allosteric ubiquitin binding enhances E2-Ub affinity for RBR E3s, suggesting a similar mechanism may operate for canonical RING E3s [8].

NMR spectroscopy offers unique insights into protein dynamics and conformational changes. Solution NMR studies have been particularly valuable for characterizing the equilibrium between open and closed states of E2∼Ub conjugates and determining how different linchpin residues affect this equilibrium [20].

Experimental Workflow for RING E3 Characterization

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for RING E3 Mechanism Studies - Comprehensive characterization involves biochemical, structural, and cellular approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions for RING E3 Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying RING E3 Mechanisms

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Stable E2∼Ub Conjugates (e.g., UbcH7(C86K)-Ub) | ITC and binding studies; structural biology | Non-hydrolyzable isopeptide linkage mimics native thioester |

| Linkage-Specific DiUbiquitin | Allosteric activation studies; signaling mechanisms | Defined ubiquitin linkages (M1, K63, K48, etc.) |

| Linchpin Mutant Series | Structure-function analysis of catalytic mechanism | Comprehensive amino acid substitutions at linchpin position |

| CRISPR-Cas9 E3 Libraries | Functional screening in cellular contexts | Identify E3 dependencies under specific conditions |

| HECT-RING Chimera Proteins | Mechanistic comparison and domain function studies | Swapped domains to identify determinative features |

The reagents listed in Table 3 represent essential tools for probing RING E3 mechanisms. Stable E2∼Ub conjugates with non-hydrolyzable linkages, such as UbcH7(C86K)-Ub that forms an isopeptide bond mimicking the native thioester, are particularly valuable for structural studies and quantitative binding measurements using ITC. These reagents allow researchers to capture and characterize the otherwise transient E2∼Ub/RING E3 complexes [8] [20].

Linkage-specific diubiquitin reagents have been crucial for identifying allosteric regulation of RING and RBR E3 ligases. For example, studies with HOIL-1 demonstrated that M1-linked diUb (EC50 = 8 μM) was more than twice as potent as K63-linked diUb (EC50 = 18 μM) as an activator, revealing specificity in allosteric regulation. Similar approaches can be applied to canonical RING E3s to identify potential regulatory mechanisms [8].

The development of linchpin mutant series has provided deep insights into the catalytic requirements of RING E3s. Systematic substitution of the linchpin residue with all 19 available amino acids, as performed with RNF38, reveals how different physicochemical properties at this position affect E2∼Ub stabilization and ubiquitination efficiency, distinguishing between residues that primarily affect binding versus those that impact catalytic conformation [20].

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The mechanistic understanding of RING E3 catalysis has significant implications for therapeutic development, particularly in the field of targeted protein degradation. Strategies such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and molecular glues harness the endogenous ubiquitination machinery, primarily RING E3 ligases, to target disease-relevant proteins for degradation. The scaffold function of RING E3s makes them ideally suited for these approaches, as they can be recruited to non-native substrates while maintaining their catalytic function [18].

Unlike traditional inhibitors that target enzyme active sites, RING E3 ligases present challenges for conventional small-molecule drug development due to their scaffold nature and lack of deep catalytic pockets. However, allosteric regulatory sites represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention. For example, the discovery that RBR E3 ligases like HOIP and RNF216 are allosterically activated by specific ubiquitin linkages suggests that small molecules mimicking or disrupting these interactions could modulate E3 activity. Similar allosteric mechanisms may exist for canonical RING E3s [8] [18].

The therapeutic potential of targeting E3 ligases is underscored by their roles in human diseases. Mutations in RING E3s such as BRCA1 (associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer), Parkin (linked to autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinsonism), and VHL (causative for von Hippel-Lindau syndrome) highlight the critical importance of these enzymes in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Understanding their catalytic mechanisms provides the foundation for developing targeted therapies that can either restore or inhibit their function, depending on the pathological context [17] [18] [22].

Emerging research continues to reveal novel aspects of RING E3 functions beyond their canonical ubiquitin ligase activities. For instance, recent studies on RNF25 have identified a role in protecting DNA replication forks that is fully separable from its ubiquitin conjugation function, suggesting that some RING E3s may have non-catalytic roles in cellular processes. This expanding functional repertoire further increases the therapeutic potential of targeting these multifunctional proteins [22].

E3 ubiquitin ligases are pivotal enzymes that confer specificity to the ubiquitination system by recognizing substrate proteins and facilitating the attachment of ubiquitin, a crucial post-translational modification. With over 600 E3 ligases encoded in the human genome, they are broadly classified into three major families based on their catalytic mechanisms: RING (Really Interesting New Gene), HECT (Homologous to the E6AP C-Terminus), and RBR (RING-Between-RING) [1] [21]. This review focuses on the structural and functional diversity within the HECT-type E3 ligases, a family characterized by a unique two-step catalytic mechanism involving a direct thioester-linked intermediate with ubiquitin [1] [8]. In contrast to RING-type E3s, which primarily function as scaffolds to directly transfer ubiquitin from an E2 enzyme to the substrate, HECT E3s first accept ubiquitin onto their catalytic cysteine residue before transferring it to the final substrate [1] [11]. This direct catalytic role necessitates distinct structural solutions for regulation and specificity.

The HECT family in humans comprises 28 members, which are further categorized into three main subfamilies: NEDD4, HERC, and Other HECT [23]. These subfamilies exhibit diverse domain architectures that dictate their cellular localization, substrate recognition capabilities, and regulatory mechanisms. Understanding the unique characteristics of each HECT subfamily is essential for appreciating their specialized roles in cellular homeostasis and their implications in human diseases, including cancer and neurological disorders [23] [24] [25]. This guide provides a structured comparison of these subfamilies, emphasizing their structural features, catalytic mechanisms, and experimental approaches for their study.

Comparative Architecture of HECT E3 Ligase Subfamilies

The defining feature of all HECT E3 ligases is the conserved ~350 amino acid HECT domain located at the C-terminus. This domain is bi-lobed, consisting of an N-lobe that interacts with the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme and a C-lobe that contains the active-site cysteine residue responsible for forming a thioester bond with ubiquitin during the catalytic cycle [1] [11]. The flexibility between these lobes, connected by a flexible hinge region, is critical for the catalytic cycle, allowing the C-lobe to access the E2-bound ubiquitin and subsequently position it for transfer to the substrate [1].

While the HECT domain is the catalytic core, the N-terminal regions of HECT E3s are highly variable and mediate substrate recognition, subcellular targeting, and regulation. The three HECT subfamilies are distinguished by their unique N-terminal domain compositions, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Domain Architecture of HECT E3 Subfamilies

| Subfamily | Representative Members | N-Terminal Domains | Distinctive Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEDD4 | NEDD4-1, NEDD4-2, ITCH, WWP1, WWP2, SMURF1, SMURF2, NEDL1, NEDL2 [23] [24] | C2 Domain (Ca²⁺/lipid-binding), 2-4 WW Domains (protein-protein interaction) [23] [24] | Largest HECT subfamily; WW domains recognize PPxY motifs on substrates; C2 domain confers membrane localization and autoinhibition [23] [26] |

| HERC | HERC1, HERC2, HERC5 [27] | RCC1-like Domains (RLDs) [27] | Giant E3s (HERC1 & HERC2 > 500 kDa); HERC5 is interferon-induced and required for ISG15 conjugation [27] |

| Other HECT | E6AP (UBE3A), HACE1, UBE3C, HUWE1 | Various domains (e.g., ARM repeats, extensions of the HECT N-lobe) [16] [11] | Defined by absence of NEDD4 or HERC architecture; E6AP is implicated in Angelman syndrome [25] |

The NEDD4 subfamily, with its characteristic C2-WW domain organization, represents the most extensively studied HECT group. The C2 domain mediates calcium-dependent phospholipid binding, targeting these E3s to cellular membranes such as the plasma membrane, endosomes, and multivesicular bodies [23]. The WW domains, containing two invariant tryptophan residues, interact with proline-rich motifs (typically PPxY) on substrate proteins and adaptors [23] [24]. Importantly, intramolecular interactions between the C2, WW, and HECT domains often serve an autoinhibitory function, maintaining the E3 in a low-activity state until specific activation signals are received [26].

Catalytic Mechanism and Ubiquitin Linkage Specificity

The catalytic mechanism of HECT E3s is a two-step process that distinguishes them from RING E3s. First, ubiquitin is transferred from the E2~Ub thioester to the catalytic cysteine in the HECT C-lobe, forming a HECT~Ub thioester intermediate. Second, ubiquitin is ligated from the HECT E3 to a lysine (or other nucleophilic residue) on the substrate protein [1] [11]. Structural studies have revealed that the HECT domain undergoes significant conformational changes during this process. The E2~Ub complex is initially recognized by the HECT N-lobe, while the C-lobe contacts the E2-bound ubiquitin. A conformational change then brings the catalytic cysteines of the E2 and HECT domains into close proximity (~8Å) for transthiolation [1] [11].

A key functional difference among HECT E3s is their inherent specificity for generating particular types of ubiquitin linkages, which determines the fate of the modified substrate. The table below summarizes the linkage preferences and functional consequences for the major HECT subfamilies.

Table 2: Ubiquitin Linkage Specificity and Functional Roles of HECT Subfamilies

| Subfamily | Preferred Ubiquitin Linkages | Primary Functional Roles | Key Substrates & Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEDD4 | K63 > K48, K29, K27; also monoubiquitination [24] | Endocytosis, lysosomal sorting, protein trafficking, signaling regulation [1] [23] [24] | PTEN (degradation), ENaC (endocytosis), Notch, TGF-β, Wnt pathways [23] [24] |

| HERC | Not fully characterized; HERC5 conjugates ISG15 (UBL) [27] | Immune response, cell cycle, DNA repair [27] | Broad spectrum of proteins during innate immune response (HERC5) [27] |

| Other HECT | Varies by member (e.g., Ufd4: K29-linked on K48 chains) [16] | Proteasomal degradation, transcription, neurodevelopment [16] [25] | p53, Sna3 (Ufd4), targets in neurodevelopment (E6AP) [16] [11] [25] |

The linkage specificity is primarily dictated by the C-lobe of the HECT domain. For instance, the last 60 amino acids of the HECT domain are critical for determining whether an E3 builds K48-linked or K63-linked chains [1]. A notable example from the "Other HECT" subfamily is Ufd4, which preferentially catalyzes the formation of K29/K48-branched ubiquitin chains on pre-assembled K48-linked ubiquitin chains, creating a potent signal for proteasomal degradation [16].

The diagram below illustrates the conserved two-step catalytic mechanism of HECT E3 ligases and the structural basis for ubiquitin chain formation.

Figure 1: Two-Step Catalytic Mechanism of HECT E3 Ligases. The process begins with the formation of a non-covalent complex between the HECT E3 and an E2~Ub thioester. The HECT N-lobe binds the E2, while the C-lobe contacts the E2-bound Ub. Step 2: Ubiquitin is transferred via transthiolation to the catalytic cysteine in the HECT C-lobe, forming a HECT~Ub intermediate. This step often involves a conformational change in the hinge region. Step 3: The HECT~Ub intermediate catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin to a lysine residue on the substrate protein via an aminolysis reaction. The C-lobe of the HECT domain determines the specificity of ubiquitin chain linkage (e.g., K48, K63, K29) [1] [11].

Experimental Approaches for Studying HECT E3 Ligases

Key Biochemical and Structural Methods

Dissecting the function and mechanism of HECT E3s relies on a suite of biochemical, biophysical, and structural techniques. The following table catalogues essential reagents and methodologies commonly employed in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for HECT E3 Ligase Studies

| Research Tool / Method | Key Function & Utility | Experimental Context & Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|

| E2-Ub Discharge Assays [8] | Measures the ability of an E3 to accept ubiquitin from a specific E2~Ub thioester. | In vitro reconstitution with purified E1, E2, E3, ubiquitin, and ATP; monitored by ubiquitin transfer to E3 catalytic cysteine via non-reducing SDS-PAGE (shift in molecular weight). |

| Ubiquitination Assays [16] | Assesses the complete E3 activity, including ubiquitin chain formation on a substrate. | Reactions include E1, E2, E3, ubiquitin, ATP, and a substrate; analyzed by Western blot to detect substrate ubiquitination (smear or shift) or by MS to determine linkage type. |

| Stable E2-Ub Conjugates (e.g., UbcH7(C86K)-Ub) [8] | Mimics the E2~Ub intermediate for structural and binding studies without catalytic turnover. | Used in Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) to quantify E2-Ub/HECT binding affinity and in crystallography to trap intermediate states. |

| Chemical Crosslinking / Trapped Complexes [16] | Stabilizes transient enzymatic intermediates for structural visualization (e.g., by Cryo-EM). | Covalently links the E3 catalytic cysteine, ubiquitin C-terminus, and substrate lysine to mimic the transition state, enabling high-resolution structure determination. |

| Linkage-Specific Di-Ub Probes [8] [16] | Investigates the role of specific ubiquitin linkages in allosteric regulation or as substrates for branched chain formation. | Used in E2-Ub discharge or ubiquitination assays to test for activation (allostery) or as substrates to determine E3 linkage preference (e.g., Ufd4 prefers K48-linked chains for K29-branching) [16]. |

| Active-Site Mutants (Cys to Ala/Ser) [24] | Generates catalytically inactive E3 for control experiments or to study substrate binding without turnover. | Used to distinguish between functional effects due to ubiquitination vs. physical interaction, and in ITC to measure E2-Ub binding without transthiolation. |

Detailed Experimental Workflow: Analyzing Ubiquitin Chain Formation

A critical experiment for characterizing any HECT E3 is the in vitro ubiquitination assay, which can delineate its linkage specificity and catalytic output. The workflow below, derived from studies on Ufd4 and other HECTs, provides a robust template [16].

Objective: To determine the ubiquitin linkage specificity of a HECT E3 ligase.

Methodology:

- Reconstitution: Set up a reaction mixture containing:

- E1 activating enzyme (e.g., Uba1)

- E2 conjugating enzyme (e.g., Ubc4 for Ufd4)

- The HECT E3 of interest (full-length or HECT domain)

- ATP (energy source)

- Wild-type ubiquitin or mutant ubiquitin (e.g., Ub-K29R, Ub-K48R)

- Optional: A substrate protein (e.g., a purified protein fragment or pre-assembled ubiquitin chains of defined linkage)

- Incubation: Allow the reaction to proceed at a physiological temperature (e.g., 30-37°C) for a defined time course.

- Termination and Analysis:

- Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer (with or without a reducing agent like DTT).

- Analyze the products by Western blotting using anti-ubiquitin antibodies to visualize overall polyubiquitin chain formation. A smear or ladder of higher molecular weight indicates successful ubiquitination.

- For linkage specificity, use linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., anti-K48, anti-K63) or perform mass spectrometric analysis (e.g., Ub-clipping/MS) on the reaction products to identify which lysine residues in ubiquitin are used for chain formation [16].

Interpretation: If the E3 shows robust activity with WT ubiquitin but significantly reduced activity with a specific ubiquitin mutant (e.g., Ub-K48R), it suggests a preference for forming chains using that lysine residue. As shown in Table 2, NEDD4-1 can generate K63-, K48-, and K29-linked chains, while Ufd4 specifically builds K29-linked branches onto K48-linked chains [24] [16].

Functional Specialization and Pathophysiological Roles

The structural diversity of HECT subfamilies underpins their specialization in distinct cellular processes and their involvement in various human diseases.

The NEDD4 subfamily members are master regulators of cell signaling and trafficking. For example, NEDD4-1 and NEDD4-2 ubiquitinate numerous plasma membrane proteins, such as ion channels (e.g., ENaC) and receptor tyrosine kinases, targeting them for endocytosis and lysosomal degradation, thereby controlling processes like sodium homeostasis and cellular growth [23] [24]. NEDD4-1's ubiquitination of the tumor suppressor PTEN can lead to its degradation, enhancing the oncogenic PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and promoting tumorigenesis [24]. The diagram below illustrates a key regulatory network centered on the NEDD4 subfamily.

Figure 2: NEDD4 Subfamily Regulatory Network in Disease and Signaling. NEDD4 subfamily E3s ubiquitinate a wide array of substrates, directing them to different cellular fates. For example, K48-linked polyubiquitination of PTEN by NEDD4-1 targets it for proteasomal degradation, leading to dysregulated PI3K/Akt signaling and potential oncogenesis. Conversely, monoubiquitination or K63-linked polyubiquitination of membrane proteins like ENaC promotes their endocytosis and lysosomal sorting, critical for maintaining ion and fluid homeostasis. The NEDD4 subfamily also attenuates signaling pathways like TGF-β and Notch by ubiquitinating their core components [23] [24].

The HERC subfamily, particularly the large HERC1 and HERC2 proteins, are involved in cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, and neurodevelopment [27]. HERC5, an interferon-induced member, plays a unique role in the innate immune response by functioning as the primary E3 ligase for the ubiquitin-like modifier ISG15, conjugating it to a broad spectrum of target proteins upon viral infection [27].

The "Other HECT" subfamily includes E3s with diverse and critical functions. E6AP (UBE3A) is perhaps the most famous, as its loss-of-function causes Angelman Syndrome, a severe neurodevelopmental disorder [25]. Maternal deficiency of UBE3A in neurons leads to dysregulation of synaptic proteins, impaired synaptic plasticity, and the characteristic symptoms of the disease [25]. Another member, Ufd4 (with human homolog TRIP12), specializes in forming K29/K48-branched ubiquitin chains, which serve as a potent signal for proteasomal degradation and are crucial for protein quality control [16].

The HECT family of E3 ubiquitin ligases represents a versatile and essential class of enzymes within the ubiquitin system. The structural and functional divergence into the NEDD4, HERC, and "Other HECT" subfamilies allows for precise spatiotemporal control over a vast array of cellular processes, from membrane trafficking and signal transduction to immune response and neural development. The defining two-step catalytic mechanism, with its central HECT~Ub thioester intermediate, provides a unique regulatory node distinct from RING E3s.

Understanding the specialized domain architecture, linkage specificity, and regulatory mechanisms of each subfamily is paramount for elucidating their physiological roles and their dysregulation in diseases such as cancer, neurodevelopmental disorders, and infection. The continued development of sophisticated experimental tools, including chemical biology probes and high-resolution structural methods, is unveiling the intricate mechanisms of ubiquitin transfer and chain formation. This knowledge not only deepens our fundamental understanding of cell biology but also paves the way for novel therapeutic strategies targeting specific HECT E3s or their substrates in human disease.

Within the ubiquitin-proteasome system, E3 ubiquitin ligases perform the crucial function of imparting substrate specificity, determining which proteins are tagged with ubiquitin for degradation or signaling purposes. The human genome encodes over 600 E3 ligases, which are categorized into three major families based on their catalytic mechanisms and structural features: RING (Really Interesting New Gene), HECT (Homologous to E6AP C-Terminus), and RBR (RING-between-RING) [1] [2]. RING-type E3s constitute the largest and most diverse family, characterized by a canonical RING finger domain that coordinates two zinc ions in a "cross-brace" structure [1] [7]. Unlike HECT and RBR E3s that form catalytic intermediates with ubiquitin, RING E3s function primarily as scaffolds that bring ubiquitin-charged E2 enzymes in close proximity to substrate proteins, facilitating direct ubiquitin transfer [8] [4]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of the major RING subfamilies—monomeric RINGs, multi-subunit Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), and RING-UIM variants—focusing on their structural architectures, catalytic mechanisms, and functional specializations within cellular regulation.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major E3 Ligase Families

| Feature | RING E3s | HECT E3s | RBR E3s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Mechanism | Direct transfer from E2 to substrate | Two-step via E3-thioester intermediate | Hybrid RING/HECT mechanism |

| Catalytic Intermediate | No | Yes (thioester with ubiquitin) | Yes (thioester with ubiquitin) |

| Representative Members | Cbl, BRCA1/BARD1, CRLs | NEDD4, E6AP, HERC | Parkin, HHARI, HOIP |

| Estimated Human Members | ~600 | ~28 | ~14 |

| Zinc Coordination | Yes (RING domain) | No | Yes (RING1, IBR, RING2 domains) |

Structural Architecture and Classification of RING E3 Ligases

The RING Domain Foundation

The RING (Really Interesting New Gene) domain serves as the structural foundation for this entire E3 ligase family. This canonical fold is characterized by a cross-brace structure that coordinates two zinc ions using specifically spaced cysteine and histidine residues [1] [7]. Structural analyses reveal that the RING domain primarily serves as a docking site for E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, positioning the thioester-linked E2~Ub conjugate for optimal ubiquitin transfer to bound substrates [7]. The RING domain itself does not form a catalytic intermediate with ubiquitin, distinguishing it fundamentally from HECT and RBR E3 mechanisms [8].

Classification by Quaternary Structure

RING E3 ligases exhibit remarkable structural diversity in their quaternary organization, which directly influences their regulatory complexity and substrate targeting capabilities:

Monomeric RING E3s: These single-polypeptide enzymes contain both substrate recognition domains and a RING finger domain within one chain. Examples include Cbl, MDM2, and RNF4, which often function in critical signaling pathways such as growth factor reception and stress response [1].

Dimeric RING E3s: These complexes form through homo- or heterodimerization of RING-containing proteins. Notable examples include the BRCA1/BARD1 heterodimer involved in DNA repair, and the MDM2/MDMX heterodimer that regulates p53 tumor suppressor stability [1]. In many heterodimers, one RING domain (e.g., in MDMX or BARD1) may lack catalytic activity but serves to stabilize the active E2-binding RING domain [1].

Multi-subunit Cullin-RING Ligases (CRLs): These represent the most complex and versatile members of the RING family. CRLs consist of a cullin scaffold protein that simultaneously binds a RING protein (RBX1 or RBX2) and various substrate receptor modules [28] [6]. The human genome encodes approximately 200 different CRL complexes, which collectively target a vast array of substrates for ubiquitination [28].

Detailed Analysis of RING Subfamilies

Mono-subunit RING E3 Ligases

Monomeric RING E3s represent the simplest architectural organization within the RING family, yet display sophisticated regulatory mechanisms. These single-polypeptide enzymes contain substrate recognition domains and a RING domain within one chain, allowing for streamlined ubiquitination of specific targets.

Structural and Functional Characteristics:

- Domain Architecture: Typically feature modular organization with specialized domains for substrate recognition (e.g., SH2 domains in Cbl, or phosphodegron recognition domains in MDM2) coupled with a C-terminal RING domain [1] [7].

- Regulatory Mechanisms: Many monomeric RING E3s are controlled by post-translational modifications or allosteric effectors. For instance, phosphorylation can enhance or suppress their E3 ligase activity by modulating E2 binding affinity or substrate accessibility [7].

- Biological Functions: Often serve as key regulators in signaling pathways—Cbl targets activated receptor tyrosine kinases for degradation, while MDM2 controls p53 tumor suppressor levels, illustrating their critical roles in cellular homeostasis [1].

Table 2: Representative Mono-subunit RING E3 Ligases

| RING E3 | Domain Organization | Primary Substrates | Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cbl | SH2 domain, RING | Receptor tyrosine kinases | Attenuation of growth signaling |

| MDM2 | p53-binding domain, RING | p53 tumor suppressor | Cell cycle regulation, apoptosis |

| RNF4 | SIM domains, RING | SUMOylated proteins | DNA damage response, quality control |

Multi-subunit Cullin-RING Ligases (CRLs)

CRLs represent the most sophisticated and versatile members of the RING family, forming modular complexes that can target numerous substrates through combinatorial assembly of interchangeable components [28] [6].

Core Architectural Components:

- Cullin Scaffold: Serves as the structural backbone that spatially organizes the complex. Different cullins (CUL1-7, CUL9) show preferences for specific substrate receptor modules [6].

- RING Box Protein (RBX1/2): Recruits and activates E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes charged with ubiquitin [28].

- Substrate Receptors: Variable components that determine substrate specificity. These include F-box proteins (for SCF complexes), BTB proteins (for CUL3 complexes), and DCAF proteins (for CUL4 complexes) [28] [6].

Regulation by Neddylation: A defining feature of CRL regulation is reversible modification by the ubiquitin-like protein NEDD8. Neddylation—the covalent attachment of NEDD8 to a conserved cullin lysine residue—induces conformational changes that enhance CRL activity by promoting a closed architecture that facilitates ubiquitin transfer [28]. This activation process is mediated by the DCNL family of co-E3 proteins, with DCNL1 being the best-characterized member [28]. Neddylation is counteracted by the COP9 signalosome (CSN), which deconjugates NEDD8 from cullins, providing a dynamic regulatory switch for CRL activity [28].

Collaboration with RBR E3s: Recent research has revealed sophisticated cooperation between CRLs and RBR E3 ligases. The RBR ligases HHARI (ARIH1) and TRIAD1 (ARIH2) interact with neddylated CRLs, leading to their activation and subsequent monoubiquitination of DCNL1 [28]. This "coupled monoubiquitylation" represents a regulatory feedback mechanism that fine-tunes CRL activity and promotes remodeling of CRL complexes [28].

RING-UIM and Specialized RING Variants

The RING-UIM represents a specialized RING variant that incorporates a Ubiquitin-Interacting Motif (UIM), enabling unique regulatory capabilities. This architectural feature allows these E3s to bind ubiquitin moieties, potentially facilitating processive ubiquitination or regulatory feedback mechanisms.

Distinctive Features:

- Ubiquitin Binding Capacity: The UIM domain enables recognition of ubiquitin molecules, which may allow these ligases to sense the ubiquitination status of their substrates or environment [7].

- Processive Ubiquitination: By binding ubiquitin chains through their UIM domains, these E3s may efficiently build extended ubiquitin chains on substrates without dissociation.

- Regulatory Feedback: Ubiquitin binding may serve as an auto-regulatory mechanism to control E3 ligase activity based on cellular ubiquitination status.

While the precise mechanistic details of RING-UIM E3s are less characterized than CRLs, they represent an important subclass that expands the functional repertoire of the RING family through integration of ubiquitin-binding capabilities.

Experimental Approaches for Studying RING E3 Mechanisms

Key Methodologies and Assays

Research into RING E3 ligase mechanisms employs a sophisticated array of biochemical, structural, and cellular approaches that provide complementary insights into their function and regulation.

Structural Biology Techniques:

- X-ray Crystallography: Has revealed atomic-level structures of RING domains in complex with E2 enzymes, illustrating the precise molecular interactions that facilitate ubiquitin transfer [1] [7].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM): Particularly valuable for visualizing large, flexible CRL complexes in different functional states [6]. Recent cryo-EM studies have captured CRLs in various conformations, providing insights into the dynamic rearrangements during the neddylation cycle.

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS): This technique probes protein dynamics and has been instrumental in understanding how neddylation activates CRLs by revealing changes in flexibility and protein-protein interactions [6].

Functional Biochemical Assays:

- E2-Ub Thioester Discharge Assays: Measure the ability of RING E3s to stimulate the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 enzymes to substrates or water [8]. This assay has been particularly useful in characterizing allosteric activation mechanisms in RBR E3s that cooperate with CRLs.

- Ubiquitination Chain Formation Assays: Utilize specialized E2 enzymes and linkage-specific antibodies to determine the types of ubiquitin chains synthesized by specific E3 ligase complexes [2].

- Neddylation/Deneddylation Assays: Monitor the addition and removal of NEDD8 from cullin scaffolds, typically using recombinant components including DCNL proteins and the CSN complex [28].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RING E3 Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| E2 Enzymes | UbcH5, UbcH7, UBE2M/UBC12 | Ubiquitination assays | Ubiquitin transfer to substrates |

| Ubiquitin Variants | Wild-type ubiquitin, Mutant ubiquitin (K48R, K63R) | Chain linkage specificity | Determining ubiquitin chain type preference |

| NEDD8 System Components | NEDD8, NAE1/UBA3, DCNL1 | Neddylation assays | CRL activation studies |

| Deubiquitinases | USP2 (pan-specific) | Ubiquitination validation | Confirming ubiquitin vs. NEDD8 modification |

| Deneddylase | NEDP1, COP9 Signalosome | Deneddylation assays | CRL inactivation studies |

Protocol: Analyzing CRL-RBR Collaborative Ubiquitination

The following methodology outlines an integrated approach to investigate the cooperative ubiquitination between CRLs and RBR E3 ligases, based on experimental approaches used in recent studies [28]:

Step 1: Reconstitution of Neddylated CRL Complex

- Purify individual CRL components (cullin, RBX1, substrate receptor) using recombinant expression systems.

- Assemble the CRL complex by incubating components in stoichiometric ratios.

- Perform neddylation reaction using UBA3-NAE1 (E1), UBE2M (E2), NEDD8, and DCNL1 co-E3 in ATP-containing buffer at 30°C for 60 minutes.

- Verify neddylation efficiency by immunoblotting using anti-NEDD8 and anti-cullin antibodies.

Step 2: Assessment of RBR E3 Activation

- Incubate neddylated CRL with RBR E3 (HHARI or TRIAD1) and E1/E2/ubiquitin components.

- Monitor RBR E3 auto-ubiquitination or substrate ubiquitination by time-course sampling.

- Analyze products by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with ubiquitin-specific antibodies.

- Include catalytically inactive RBR mutants (C310S for TRIAD1, C357S for HHARI) as negative controls.

Step 3: Detection of Coupled Monoubiquitination

- Test for DCNL1 monoubiquitination in the presence of active RBR E3 and neddylated CRL.

- Use USP2 treatment to confirm ubiquitin (vs. NEDD8) modification of DCNL1.

- Employ UBA domain mutants of DCNL1 to verify specificity of the ubiquitination mechanism.

Comparative Mechanisms: RING versus HECT E3 Ligases

Understanding the distinctions between RING and HECT E3 mechanisms provides crucial insights for targeted therapeutic development and fundamental cell biology research.

Catalytic Mechanism Differences:

- RING E3s: Function as scaffolds that facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate without forming a covalent intermediate. They typically act as allosteric activators of E2 enzymes [1] [7].

- HECT E3s: Employ a two-step catalytic mechanism involving a covalent thioester intermediate between the HECT domain catalytic cysteine and ubiquitin, before final transfer to the substrate [2] [4].

Structural Organization:

- RING E3s: Display tremendous architectural diversity—from single polypeptide chains to massive multi-subunit complexes—all centered around the conserved RING domain that recruits E2 enzymes [7].

- HECT E3s: Feature a conserved C-terminal HECT domain (approximately 350 amino acids) connected to variable N-terminal substrate recognition domains. The HECT domain itself is bi-lobed, with the N-lobe binding E2 and the C-lobe containing the catalytic cysteine [2] [4].

Regulatory Complexity:

- RING E3s: Often regulated by complex assembly/disassembly (as in CRLs), post-translational modifications, or interaction with adaptor proteins. The neddylation/deneddylation cycle represents a particularly sophisticated regulatory mechanism for CRLs [28] [6].

- HECT E3s: Frequently controlled by autoinhibitory intramolecular interactions, adaptor proteins that modulate E2 binding (e.g., SMAD7 for SMURFs), or post-translational modifications that relieve autoinhibition [4].

Therapeutic Targeting Considerations: The mechanistic differences between RING and HECT E3s present distinct challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. RING E3s, particularly CRLs, offer targets for small molecules that disrupt specific protein-protein interactions within multi-subunit complexes [28] [6]. The neddylation pathway represents an attractive target for cancer therapy, with MLN4924 (a NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor) already in clinical trials. HECT E3s, with their conserved catalytic cysteine, may be susceptible to covalent inhibitors that target the active site, though achieving specificity remains challenging [4].

The structural diversity within the RING E3 ligase family—from monomeric forms to elaborate CRL complexes—enables the exquisite specificity and dynamic regulation required for cellular homeostasis. The recent discovery of collaborative mechanisms between CRLs and RBR E3s, such as the coupled monoubiquitylation of DCNL1 by TRIAD1 and HHARI, reveals an additional layer of complexity in the ubiquitin system [28]. These findings highlight the sophisticated regulatory networks that connect different E3 ligase families, suggesting an integrated cellular management system for protein ubiquitination.

Future research directions will likely focus on elucidating the full complement of CRL-RBR partnerships, developing technologies to monitor E3 ligase activity in real-time within living cells, and leveraging structural insights for targeted therapeutic development. The expanding toolkit of degrader technologies, including PROTACs that harness endogenous E3 machinery for targeted protein degradation, underscores the translational importance of understanding RING E3 mechanisms. As our structural and mechanistic knowledge deepens, so too will our ability to manipulate these essential regulatory complexes for therapeutic benefit across diverse disease contexts, from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders.

Research Tools and Therapeutic Targeting Strategies

Ubiquitin ligases (E3s) are pivotal specificity determinants in the ubiquitin system, responsible for recognizing substrates and mediating the attachment of ubiquitin. They are broadly classified into three families based on their catalytic mechanisms: RING (Really Interesting New Gene), HECT (Homologous to E6AP C-terminus), and RBR (RING-between-RING) types [2] [29]. Understanding the distinct catalytic mechanisms of these E3s is essential for deciphering their biological functions and developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

The ubiquitin discharge assay and the auto-ubiquitylation assay are two fundamental biochemical tools used to dissect E3 ligase activity. The discharge assay specifically probes the first catalytic step—the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to the E3—making it particularly valuable for HECT and RBR-type ligases that form a transient E3~Ub thioester intermediate [29] [8]. In contrast, the auto-ubiquitylation assay monitors the complete catalytic cycle, including the final transfer of ubiquitin to a lysine residue on the E3 itself or an associated substrate. This assay is applicable to all E3 classes and can provide insights into both enzyme activity and chain-building capabilities [30] [5]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these assays, their applications, and the critical insights they yield for the study of HECT versus RING E3 ligase mechanisms.

Comparative E3 Ligase Mechanisms

Catalytic Mechanisms of HECT, RING, and RBR E3 Ligases

Table 1: Comparative Catalytic Mechanisms of E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families

| E3 Family | Catalytic Mechanism | Key Intermediate | Representative Members |

|---|---|---|---|

| HECT | Two-step mechanism; E3~Ub thioester intermediate formed on a catalytic cysteine before substrate transfer [31] [2]. | Yes (HECT~Ub) | Rsp5, NEDD4, HUWE1, HACE1 [31] [2] [32] |

| RING | One-step mechanism; acts as a scaffold to facilitate direct Ub transfer from E2~Ub to the substrate [33] [7]. | No | RNF4, cIAP2, MIB1 [33] [7] [5] |

| RBR | Hybrid mechanism; RING1 domain binds E2~Ub, and Ub is transferred to a catalytic cysteine in RING2 before substrate transfer [29] [8]. | Yes (RING2~Ub) | Parkin, HOIP, HOIL-1, HHARI [29] [8] |