In Vitro Polyubiquitin Chain Formation: Methods, Applications, and Advanced Characterization Techniques

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers studying polyubiquitin chain formation in vitro.

In Vitro Polyubiquitin Chain Formation: Methods, Applications, and Advanced Characterization Techniques

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers studying polyubiquitin chain formation in vitro. It covers the foundational principles of ubiquitin chain architecture, including homotypic, heterotypic, and branched chains, and their distinct biological functions. We detail state-of-the-art methodologies for the enzymatic, chemical, and hybrid synthesis of defined chain linkages. The content further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for chain assembly and purification. Finally, we explore advanced validation techniques, including linkage-specific binding assays and functional readouts, crucial for interpreting experimental data and advancing drug discovery efforts in the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Understanding the Ubiquitin Code: Architectures and Biological Signals of Polyubiquitin Chains

Ubiquitylation is an essential post-translational modification that controls a wide variety of eukaryotic cellular processes, including protein degradation, cell signaling, DNA repair, and inflammation [1] [2]. The versatility of ubiquitin as a signal stems from its capacity to form diverse architectural structures when conjugated to substrate proteins. Ubiquitin can be attached to substrates as a single moiety (monoubiquitination), as multiple single ubiquitins (multi-monoubiquitination), or as polymeric chains (polyubiquitination) [1] [2]. Polyubiquitin chains are formed when the C-terminal glycine of a donor ubiquitin forms an isopeptide bond with a specific acceptor site on the preceding ubiquitin molecule. Ubiquitin contains eight primary acceptor sites: the α-amino group of the N-terminal methionine (M1) and the ε-amino groups of seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) [3] [4].

These chains can be classified into three major topological categories based on their linkage patterns:

- Homotypic chains: Composed of ubiquitin monomers linked uniformly through the same acceptor site (e.g., K48-linked chains).

- Heterotypic mixed chains: Composed of more than one linkage type, but each ubiquitin monomer is modified on only a single acceptor site.

- Heterotypic branched chains: Contain at least one ubiquitin subunit that is concurrently modified on two or more different acceptor sites, creating a forked structure [1] [2].

The specific topology of a ubiquitin chain dictates its biological function, with different architectures being recognized by distinct effector proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) [4]. For instance, K48-linked homotypic chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains are often involved in non-proteolytic processes like kinase activation and DNA repair. Branched chains have recently emerged as potent regulatory signals, often enhancing the efficiency of protein degradation or organizing large signaling complexes [1] [5].

Table 1: Characteristics and Functions of Major Ubiquitin Chain Types

| Chain Type | Primary Linkage(s) | Structural Classification | Known Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homotypic | K48, K63, K11, K29, M1, etc. | Uniform linkage throughout the chain | K48: Proteasomal degradation [2] [4]K63: DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis [2] [4]M1: NF-κB activation [4] |

| Branched | K11/K48, K29/K48, K48/K63, K6/K48 | One ubiquitin monomer modified on ≥2 sites | Potent degradation signal [1]Amplification of homotypic chain signals [5]Activation and inactivation of signaling pathways [2] |

Table 2: Enzymatic Machinery for Branched Ubiquitin Chain Assembly (Select Examples)

| Branching Enzyme(s) | Linkage Type Synthesized | Mechanism of Assembly | Biological Context / Substrate |

|---|---|---|---|

| APC/C + UBE2C + UBE2S [1] | K11/K48 | Sequential action of two E2s (UBE2C then UBE2S) on a single RING E3 | Mitotic substrates (e.g., Cyclin A) [1] |

| ITCH + UBR5 [1] [2] | K48/K63 | Collaboration between two HECT E3s with distinct specificities | Apoptotic regulator TXNIP [1] [2] |

| Ufd4 + Ufd2 [1] [2] | K29/K48 | Collaboration between HECT and U-box E3s | Ubiquitin Fusion Degradation (UFD) pathway substrates [1] [2] |

| Parkin [1] | K6/K48 | Single RBR E3 with innate branching activity | In vitro substrates [1] |

| cIAP1 [1] | K11/K48, K48/K63 | Sequential action of E2s UBE2D and UBE2N-UBE2V1 | Chemically induced degradation of ER-α [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Ubiquitin Chain Linkage In Vitro

This protocol details how to determine the linkage of ubiquitin chains formed on a substrate of interest during in vitro ubiquitination reactions, using linkage-specific ubiquitin mutants [3].

Materials and Reagents

- E1 Enzyme: 5 µM stock concentration.

- E2 Enzyme: 25 µM stock concentration. The choice of E2 should be compatible with your E3 ligase.

- E3 Ligase: 10 µM stock concentration.

- 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer: 500 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM TCEP.

- Ubiquitin and Mutants: 1.17 mM (10 mg/mL) stock concentrations for:

- Wild-Type Ubiquitin

- Ubiquitin K to R Mutants (Seven): K6R, K11R, K27R, K29R, K33R, K48R, K63R. Each mutant lacks a single lysine, which prevents chain formation if that lysine is required for linkage.

- Ubiquitin K Only Mutants (Seven): K6 Only, K11 Only, K27 Only, K29 Only, K33 Only, K48 Only, K63 Only. Each mutant contains only one lysine, forcing all chains to use that specific linkage.

- MgATP Solution: 100 mM stock concentration.

- Substrate Protein: The protein to be ubiquitinated.

- Termination Reagents: 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer, or 500 mM EDTA / 1 M DTT for downstream applications.

- Equipment: Microcentrifuge tubes, 37°C water bath, Western Blot equipment.

Procedure

Part A: Initial Linkage Determination with K-to-R Mutants

Reaction Setup: Set up nine separate 25 µL reactions. Each reaction should contain:

- Reactions 1-8: One type of ubiquitin (Wild-Type, K6R, K11R, K27R, K29R, K33R, K48R, K63R).

- Reaction 9 (Negative Control): Wild-Type Ubiquitin, but replace MgATP with dH₂O.

Assemble each reaction on ice in the following order:

Reagent Volume Final Concentration dH₂O To 25 µL - 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer 2.5 µL 1X Ubiquitin (or K-to-R Mutant) 1 µL ~100 µM MgATP Solution 2.5 µL 10 mM Substrate Protein Variable 5-10 µM E1 Enzyme 0.5 µL 100 nM E2 Enzyme 1 µL 1 µM E3 Ligase Variable 1 µM Incubation: Incubate all reactions in a 37°C water bath for 30-60 minutes.

- Termination: Stop the reactions based on downstream use:

- For direct analysis: Add 25 µL of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- For downstream applications: Add 0.5 µL of 500 mM EDTA (20 mM final) or 1 µL of 1 M DTT (100 mM final).

- Analysis: Analyze the reactions by Western blot using an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

- Interpretation: The reaction containing the K-to-R mutant that is unable to form polyubiquitin chains (showing only monoubiquitination) indicates the essential lysine for linkage. For example, if only the K63R mutant reaction fails to form chains, the linkage is K63. If all mutants form chains, the linkage may be M1 (linear) or the chains may be mixed/branched [3].

Part B: Linkage Verification with K-Only Mutants

- Reaction Setup: Set up another nine 25 µL reactions as in Part A, but replace the K-to-R mutants with the seven "K Only" ubiquitin mutants.

- Incubation and Analysis: Repeat steps 2-4 from Part A.

- Interpretation: Only the wild-type ubiquitin and the "K Only" mutant corresponding to the correct linkage will form polyubiquitin chains. For example, for a K63-linked chain, only the Wild-Type and K63 Only ubiquitin will produce chains [3].

Data Interpretation and Troubleshooting

- Simple Homotypic Chain: The data will clearly point to a single lysine being necessary and sufficient for chain formation.

- Mixed or Branched Chains: If the results from the K-to-R and K-Only mutant assays are inconsistent or suggest dependence on multiple lysines, this indicates the formation of heterotypic chains [3]. Further analysis, such as mass spectrometry, is required to distinguish between mixed and branched topologies.

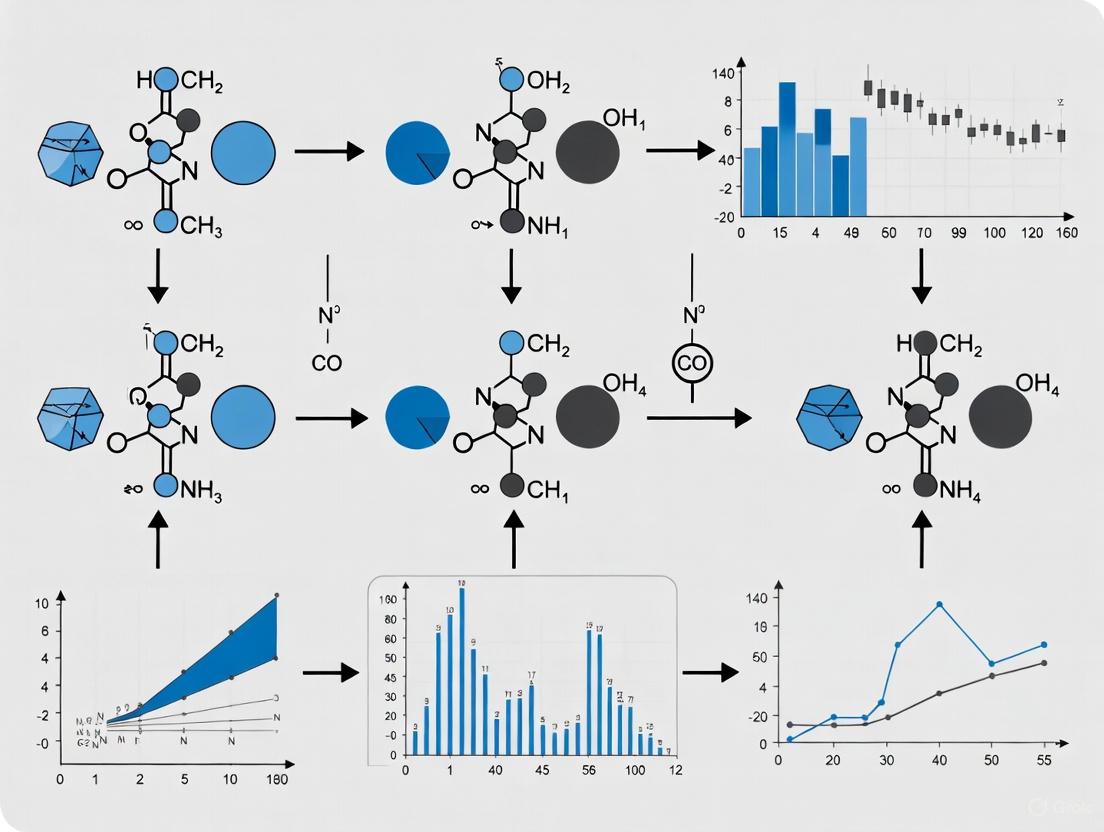

Visualizing the Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade and Linkage Determination Workflow

Diagram 1: Workflow for in vitro ubiquitin chain assembly and linkage determination.

Diagram 2: Architectural diversity of polyubiquitin chains. Branched chains contain a ubiquitin monomer modified at two sites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for In Vitro Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzyme | Initiates the ubiquitination cascade by activating ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner; essential for all in vitro ubiquitination reactions [3]. |

| E2 Conjugating Enzymes (e.g., UBE2C, UBE2S, UBE2D) | Accepts ubiquitin from E1 and cooperates with E3 ligases to determine chain linkage specificity. Different E2s are responsible for different linkages [1] [4]. |

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligases (e.g., APC/C, Parkin, TRAF6) | Confers substrate specificity and often determines the topology of the ubiquitin chain. Different classes (RING, HECT, RBR) employ distinct catalytic mechanisms [1] [2] [4]. |

| Wild-Type Ubiquitin | The standard, unmodified form of ubiquitin used as a positive control in conjugation assays [3]. |

| Ubiquitin K-to-R Mutant Set | Collection of ubiquitin mutants where a single lysine is changed to arginine. Used to identify the specific lysine residue essential for polyubiquitin chain formation [3]. |

| Ubiquitin K-Only Mutant Set | Collection of ubiquitin mutants where only one lysine remains functional. Used to verify chain linkage, as chains can only form via the single available lysine [3]. |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | Enzymes that cleave ubiquitin chains. Used to confirm the identity of ubiquitin modifications and to study chain dynamics and editing [1] [5]. |

Quantitative Analysis of Polyubiquitin Linkages

The functional diversity of ubiquitin signaling is rooted in the structural heterogeneity of polyubiquitin chains. Quantitative mass spectrometry has revealed the relative abundance and specific roles of different chain linkages.

Table 1: Absolute Abundance and Functional Roles of Ubiquitin Linkages in Log-Phase Yeast [6]

| Ubiquitin Linkage | Percent Abundance (%) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | 29.1 ± 1.9 | Canonical proteasomal degradation signal. |

| K63 | 16.3 ± 0.2 | Non-proteolytic signaling (DNA repair, inflammation, endocytosis). |

| K11 | 28.0 ± 1.4 | Proteasomal degradation; key for ERAD and cell cycle regulation. |

| K6 | 10.9 ± 1.9 | Potential role in DNA repair; accumulates upon proteasomal inhibition. |

| K27 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | Role in stress response; accumulates upon proteasomal inhibition. |

| K33 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | Role in stress response; accumulates upon proteasomal inhibition. |

| K29 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | May participate in Ub-fusion degradation; accumulates upon proteasomal inhibition. |

Table 2: Functional Hierarchy of Defined Ubiquitin Chains in a Cellular Degradation Assay (UbiREAD) [7]

| Ubiquitin Chain Topology | Degradation Outcome | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|

| K48-Ub~3~ | Rapid degradation (half-life ~1 min) | Serves as a minimal, efficient proteasomal targeting signal. |

| K63-Ub~n~ | Rapid deubiquitination, not degradation | Resists degradation, consistent with non-proteolytic role. |

| K48-K63 Branched (K48-anchored) | Degradation | Substrate-anchored chain identity dictates fate; K48 branch dominates. |

| K48-K63 Branched (K63-anchored) | Deubiquitination | Substrate-anchored chain identity dictates fate; K63 branch is subordinate. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To isolate ubiquitinated proteins and absolutely quantify the levels of all seven polyubiquitin chain linkages from cell lysates.

Workflow:

Key Reagents and Solutions:

- Lysis Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, supplemented with protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF) and deubiquitinase inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide).

- Affinity Resin: Ni-NTA Agarose for His-tagged ubiquitin purifications.

- Digestion Buffer: 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0.

- Sequencing Grade Trypsin.

- Internal Standards: Synthetic, heavy isotope-labeled peptides corresponding to tryptic ubiquitin fragments with a GG-remnant on each lysine (e.g., TLTGK~GG~TITLEVEPSDTIENVK).

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Harvest 1-5 x 10^7 cells and lyse in 1 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer for 30 minutes. Clear the lysate by centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Affinity Purification: Incubate the supernatant with 50 μL of pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA resin for 2 hours at 4°C with end-over-end rotation.

- Washing: Wash the resin 3-4 times with 10 column volumes of lysis buffer, followed by two washes with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0.

- On-Bead Digestion: Resuspend the resin in 100 μL of digestion buffer. Add 2 μg of trypsin and incubate overnight at 37°C with shaking.

- Peptide Preparation: Acidify the digest with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Desalt the peptides using C18 stage tips.

- MS Analysis: Reconstitute peptides in 0.1% formic acid and analyze by LC-MS/MS. Spike in a known amount of heavy isotope-labeled internal standard peptides prior to injection for absolute quantification.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the abundance of each native linkage-specific peptide by comparing its signal intensity to that of its corresponding heavy standard.

Objective: To test the ability of the Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) with its E2 UbcH10 to assemble K11-linked chains and trigger degradation of a substrate.

Workflow:

Key Reagents and Solutions:

- Purified Proteins: Recombinant human APC/C, UbcH10 (charged with ubiquitin, E2~Ub~), APC/C substrate (e.g., cyclin B1 or securin), and wild-type/mutant ubiquitin (e.g., ubi-K11, ubi-K48, ubi-R11).

- Energy Regeneration System (10X): 300 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 30 mM ATP, 300 mM MgCl₂, 150 mM creatine phosphate.

- Ubiquitination Reaction Buffer (1X): 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Tween-20.

- Xenopus Egg Extracts or CP-extracts: For monitoring substrate degradation in a physiological context.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: For a 50 μL reaction, combine on ice:

- 5 μL 10X Energy Regeneration System

- 10-50 nM APC/C-Cdh1

- 100-500 nM UbcH10~Ub~

- 1-5 μM APC/C substrate

- 50-100 μM of specified ubiquitin mutant (ebi-K11, ubi-K48, etc.)

- Ubiquitination Reaction Buffer to volume.

- Time-Course Incubation: Transfer the reaction to a 30°C heat block. Remove 10 μL aliquots at time points (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60 minutes) and immediately stop the reaction by adding 4X SDS-PAGE loading buffer with DTT.

- Analysis:

- Ubiquitination: Resolve time-point samples by SDS-PAGE and perform Western blotting using an antibody against your substrate. K11-linkage formation can be confirmed using linkage-specific antibodies.

- Degradation in Extracts: Supplement mitotic or G1 cell extracts with UbcH10/p31comet and the specified ubiquitin mutant. Take aliquots over time and analyze by Western blotting for endogenous substrate (e.g., cyclin B1) degradation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying Polyubiquitin Chain Formation and Function

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Utility | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Mutants (e.g., ubi-K11, ubi-K48, ubi-K63, ubi-R11) | Determines if a specific linkage is necessary or sufficient for a biological process. | Testing if ubi-K11 alone supports APC/C-mediated degradation [8]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Immunodetection of endogenous chains of a specific topology via Western blot or immunofluorescence. | Confirming accumulation of K11-linked chains upon proteasomal inhibition [6]. |

| Recombinant E2-E3 Pairs (e.g., APC/C-UbcH10, TRAF6-HUWE1) | Reconstitute linkage-specific ubiquitination in a minimal in vitro system. | Demonstrating UbcH10 specificity for K11-linked chain assembly [8]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, PS341/Bortezomib) | Blocks degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, causing accumulation of proteasomal substrates. | Revealing that all non-K63 linkages accumulate when degradation is blocked [6]. |

| UbiREAD Technology | Systematically compares degradation kinetics of substrates modified with defined ubiquitin chains delivered into living cells. | Establishing that K48-Ub3 is a minimal degradation signal and revealing hierarchy in branched chains [7]. |

Post-translational modification of proteins by polyubiquitin chains is a fundamental regulatory mechanism controlling a vast array of processes in eukaryotic cells, including targeted protein degradation, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and inflammatory response [9] [10]. The functional outcome of polyubiquitination depends critically on the conformational properties of the chain, which are primarily determined by the specific lysine residue used for linkage between ubiquitin monomers [9]. These linkage-dependent conformations create distinct molecular surfaces that are selectively recognized by ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) present in receptor proteins, thereby translating the ubiquitin signal into specific cellular responses [10]. This application note provides a detailed framework for studying polyubiquitin chain conformations in vitro, with particular emphasis on distinguishing between closed and extended configurations and their selective recognition by ubiquitin-binding proteins.

Structural Basis of Polyubiquitin Conformations

Fundamental Structural Elements

The ubiquitin monomer contains several key structural features that dictate the conformational properties of polyubiquitin chains:

- Hydrophobic patch: A critical surface region comprising residues L8, I44, and V70 that serves as the primary "binding hot spot" for both Ub-Ub interactions and recognition by UBDs [9].

- Flexible C-terminus: The region containing residues R72-G76 provides conformational flexibility that enables ubiquitin to form chains with different lysine linkages [9].

- Lysine residues: Seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and the N-terminal methionine (M1) serve as potential linkage sites for chain formation [11] [12].

Closed vs. Extended Conformations

Polyubiquitin chains exist in dynamic equilibrium between different conformational states, with the closed and extended configurations representing two principal forms:

Table 1: Characteristics of Closed vs. Extended Polyubiquitin Conformations

| Feature | Closed Conformation | Extended Conformation |

|---|---|---|

| Ub-Ub Interface | Extensive hydrophobic contacts between adjacent Ub units | Minimal or no hydrophobic contacts between Ub units |

| Hydrophobic Patch Accessibility | Sequestered at Ub-Ub interface | Exposed and available for interactions |

| Primary Linkages | K48, K6, K11, K27 [9] | K63, K29, K33, M1-linked (linear) [9] |

| Functional Roles | Primarily proteasomal degradation [9] [13] | Non-proteolytic signaling (DNA repair, inflammation, kinase activation) [9] [14] |

| Structural Features | Compact globular arrangement | Open, flexible arrangement |

Recent evidence suggests that this binary classification represents extremes in a conformational continuum. For instance, K63-linked diubiquitin (K63-Ub2) exists as a dynamic ensemble comprising multiple closed and open quaternary states, with ligand binding selecting and stabilizing specific pre-existing conformations [14].

Quantitative Analysis of Polyubiquitin Chain Properties

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Properties of Different Polyubiquitin Linkages

| Linkage Type | Predicted Conformation | Buried Surface Area (Ų) | Transition Temperature (K) | Functional Specialization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Closed [9] | 1458 [9] | ~353 [12] | Proteasomal degradation [9] [13] |

| K63 | Extended [9] | 736 [9] | ~353 [12] | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling [14] |

| K6 | Closed [9] | N/A | N/A | DNA damage response [13] |

| K11 | Closed [9] | Consistent with protein complexes [9] | N/A | ER-associated degradation [13] |

| K27 | Closed (with limitations) [9] | N/A | N/A | Immune signaling [13] |

| K29 | Extended [9] | N/A | N/A | Proteasomal degradation [13] |

| K33 | Extended [9] | N/A | N/A | Kinase regulation [13] |

| Linear (M1) | Extended [9] | N/A | ~348 [12] | NF-κB signaling [13] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Molecular Modeling of Diubiquitin Conformations

Purpose: To predict whether specific ubiquitin linkages can adopt closed conformations via hydrophobic patch-to-patch contacts.

Methodology:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain high-resolution structures of ubiquitin monomers (PDB ID: 1UBQ).

- Chain Generation: Generate diubiquitin chains for all seven possible isopeptide linkages and head-to-tail linear chains using molecular docking software.

- Constraint Definition:

- Apply ambiguous restraints defining active and passive residues corresponding to the hydrophobic patch (L8, I44, V70) on each ubiquitin.

- Implement unambiguous distance restraints based on typical interatomic distances for isopeptide bonds in crystal structures [9].

- Structure Calculation: Use HADDOCK software for docking calculations, accounting for both ambiguous and unambiguous distance constraints [9].

- Cluster Analysis: Subject resulting structures to clustering analysis and rank clusters according to HADDOCK score (Hscore). Retain ten best structures in each cluster for further analysis.

Expected Outcomes: Classification of ubiquitin linkages into two groups: those capable of forming closed conformations (K6, K11, K27, K48) and those unable to form such contacts due to steric occlusion (K29, K33, K63, head-to-tail) [9].

Protocol 2: Middle-Down Mass Spectrometry for Chain Architecture Analysis

Purpose: To characterize both length and linkage topology of polyubiquitin chains without requiring isotope-labeled internal standards.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Isolate polyubiquitin chains from biological sources using nickel affinity chromatography (for His-tagged Ub) or immunopurification with linkage-specific antibodies [11] [15].

- Partial Tryptic Digestion:

- Prepare digestion reactions containing 5 μg/mL ubiquitin and 5 μg/mL trypsin in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 7.8).

- Incubate at 37°C or room temperature for optimized duration to achieve exclusive cleavage at R74 [11].

- Reaction Termination: Add formic acid to 1% final concentration.

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Load samples on reverse phase column (C8 resin).

- Elute using 20-40% gradient over appropriate timeframe.

- Analyze using high-resolution mass spectrometry (e.g., LTQ-Orbitrap) [11].

- Data Interpretation:

- Identify UbR74 (residues 1-74) and its ubiquitinated form with diglycine tag (UbR74-GG).

- Calculate chain length based on molar ratio between UbR74 and UbR74-GG (1:1 for dimer, 1:2 for trimer, 1:3 for tetramer).

- Determine linkage specificity through MS/MS and MS/MS/MS analysis of large GG-tagged Ub fragments [11].

Applications: Analysis of homogeneous polyubiquitin chains, identification of lysine residues used for chain linkages, detection of forked chains with mixed linkages [11].

Protocol 3: NMR Analysis of Polyubiquitin Dynamics and Recognition

Purpose: To characterize conformational ensembles of polyubiquitin chains and their interactions with ubiquitin-binding domains.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Express and purify 15N-labeled ubiquitin and diubiquitin proteins.

- Synthesize linkage-specific diubiquitin using appropriate E2 enzymes (e.g., E2-25K for K48-linkages, Ubc13/MMS2 for K63-linkages) [16].

- NMR Experiments:

- Acquire 1H,15N HSQC spectra to monitor chemical shift perturbations.

- Perform paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) experiments by introducing cysteine point mutations at specific sites (e.g., N25C or K48C) and conjugating MTS paramagnetic probes [14].

- Titration Studies: Incrementally add unlabeled binding partners (UBDs, E2 enzymes) to 15N-labeled polyubiquitin and monitor chemical shift changes.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate binding affinities from chemical shift perturbations.

- Refine against inter-subunit PRE data to determine ensemble structures.

- Generate models of complexes using RosettaDock modeling suite [16].

Applications: Mapping interaction surfaces, determining binding affinities, characterizing conformational dynamics, and elucidating recognition mechanisms [16] [14].

Visualization of Polyubiquitin Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Polyubiquitin Conformation Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Features / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Diubiquitins | Structural and binding studies | Commercially available (Boston Biochem) or enzymatically synthesized using specific E2s [16] [11] |

| HADDOCK Software | Molecular docking of ubiquitin complexes | Accounts for ambiguous and unambiguous distance constraints [9] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins with specific chain linkages | M1-, K11-, K27-, K48-, K63-linkage specific antibodies [15] |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitinated substrates [15] |

| NMR with PRE | Characterization of conformational dynamics and transient interactions | Sensitive to transient interactions and ensemble structures [14] |

| Middle-Down MS | Analysis of chain length and linkage architecture | Partial tryptic digestion at R74; no isotope labels required [11] |

The structural characterization of polyubiquitin chain conformations and their selective recognition represents a critical frontier in understanding ubiquitin signaling. The experimental approaches outlined in this application note provide researchers with robust methodologies for investigating the relationship between ubiquitin linkage, chain conformation, and functional specificity. As research in this field advances, the integration of biophysical, computational, and proteomic techniques will continue to reveal the intricate mechanisms by which the ubiquitin code is written, read, and erased in cellular regulation and disease pathogenesis.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a crucial regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells, controlling protein stability, function, and localization. Central to this system is the enzymatic cascade comprising E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligating) enzymes, which collectively mediate the attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins. The specificity of ubiquitin chain linkage—determined by which of the seven lysine residues or the N-terminus of one ubiquitin molecule connects to the next—encodes distinct functional outcomes for the modified substrate. While E2 enzymes possess intrinsic chain-type preferences, emerging research demonstrates that E3 ligases exert ultimate authority in determining chain topology, transforming promiscuous E2 activity into highly specific ubiquitination signals with profound biological consequences [17] [18]. Understanding this hierarchical control is essential for manipulating ubiquitin signaling in therapeutic contexts, particularly in drug development campaigns targeting protein degradation pathways.

Mechanistic Insights: Hierarchical Control of Ubiquitin Chain Specificity

The Enzymatic Cascade and Chain-Type Diversity

Protein ubiquitination proceeds through a well-defined three-step enzymatic cascade. The E1 enzyme initiates the process by activating ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, forming a thioester bond with ubiquitin's C-terminus. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the catalytic cysteine of an E2 enzyme. Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the target substrate [19] [20]. When multiple ubiquitin molecules are attached to one another, they form polyubiquitin chains with distinct functional properties based on their linkage topology.

The human genome encodes a remarkable diversity of components in this system: 2 E1 enzymes, approximately 40 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases [18]. This extensive combinatorial potential allows for exquisite specificity in substrate selection and modification type. The eight possible linkage types (M1, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) create a complex "ubiquitin code" that determines the fate of modified proteins, with K48-linked chains primarily targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation and K63-linked chains regulating signal transduction, protein trafficking, and DNA repair [21] [22] [23].

E2 Enzymes: Intrinsic Specificity and Promiscuity

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes exhibit inherent preferences for specific ubiquitin linkage types. Structural studies reveal that E2s contain defining regions that influence which lysine residue of ubiquitin they preferentially target for chain formation. This intrinsic specificity stems from the E2's ability to position the donor ubiquitin (thioester-linked to the E2 active site) and acceptor ubiquitin (typically substrate-linked) in orientations that favor particular linkage geometries [17] [18].

However, this E2-intrinsic specificity is often broad and promiscuous. Experimental evidence demonstrates that tethering a substrate directly to an E2 enzyme in the absence of an E3 ligase results in ubiquitination with promiscuous chain types and modification of non-specific lysine residues on the substrate [17]. This suggests that while E2 enzymes possess the catalytic machinery for ubiquitin transfer, they lack the requisite precision for physiologically relevant target selection and chain specification alone.

E3 Ligases: The Ultimate Determinants of Specificity

E3 ubiquitin ligases serve as the crucial specificity factors in the ubiquitination cascade, transforming the broad potential of E2 enzymes into precisely defined ubiquitination events. Introduction of an E3 ligase to the reaction creates a clear decision point between mono- and polyubiquitination and imposes strict specificity regarding both the target lysine on the substrate and the type of ubiquitin chain assembled [17].

E3 ligases achieve this precision through several complementary mechanisms:

- Substrate positioning: E3s precisely orient the substrate relative to the E2~ubiquitin complex to direct ubiquitin transfer to specific lysine residues

- E2 recruitment: Selective binding to particular E2 enzymes based on complementary structural features

- Allosteric regulation: Some E3s undergo conformational changes that activate or modify the E2's catalytic properties

- Processivity control: Regulation of chain elongation through processive or distributive mechanisms

The critical role of E3s is exemplified by studies showing that the same E2 enzyme can produce different chain linkages when paired with different E3 partners [17] [18]. Furthermore, auxiliary factors can reconfigure E3 specificity, as demonstrated by MDMX's ability to modulate MDM2-dependent ubiquitination of p53 [17].

Experimental Approaches and Key Findings

Quantitative Analysis of Enzymatic Specificity

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings on Enzyme Specificity in Ubiquitin Chain Formation

| Experimental System | Key Finding | Impact on Specificity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| E2-substrate tethering (without E3) | Promiscuous ubiquitination patterns; non-specific lysine targeting | Demonstrates E2's intrinsic but broad specificity | [17] |

| E2-E3 paired systems | Clear decision between mono-/polyubiquitination; specific lysine targeting | E3 imposes strict specificity on E2 activity | [17] |

| MDM2-MDMX-p53 system | Auxiliary factors reconfigure E3 specificity | E3 specificity can be dynamically regulated | [17] |

| Phage display profiling of E1 specificity | E1 exhibits substantial promiscuity toward UB C-terminal sequences | Specificity increases through cascade | [20] |

| Kinetic modeling of polyubiquitination | Bistable, switch-like responses in chain formation dynamics | System properties emerge from enzymatic cascade | [19] |

Methodologies for Assessing Chain Specificity

Researchers have developed several robust experimental approaches for dissecting the contributions of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes to ubiquitin chain specificity:

In Vitro Reconstitution assays These experiments involve purifying individual enzymatic components and reconstituting the ubiquitination cascade in controlled environments. Typical protocols include:

- Incubation of 15-50μL of substrate-bound beads with 30-100nM E1, 1-5μM E2, and 0.5-2μM E3 in reaction buffer containing 50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5mM MgCl₂, 2mM ATP, and 0.5mM DTT

- Time-course sampling from 5-60 minutes at 30°C followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with linkage-specific antibodies

- Variation of E2-E3 combinations while keeping other factors constant to assess specificity contributions [17]

TUBE-based Capture Technology Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) engineered with nanomolar affinities for specific polyubiquitin linkages enable high-throughput assessment of chain specificity:

- Coating 96-well plates with chain-specific TUBEs (K48-selective vs. K63-selective)

- Incubating cell lysates with TUBE-coated plates for 2-4 hours at 4°C

- Washing and detecting captured ubiquitinated proteins with target-specific antibodies

- This approach successfully differentiated K63-linked ubiquitination of RIPK2 induced by L18-MDP from K48-linked ubiquitination induced by PROTAC treatment [21] [23]

Phage Display Profiling This method maps specificity determinants by displaying ubiquitin variants with randomized C-terminal sequences:

- Construction of UB library with randomized residues 71-75 while preserving Gly76

- Iterative selection rounds with biotinylated E1 enzymes immobilized on streptavidin plates

- Stringency increases through reduced reaction time and enzyme concentration in successive rounds

- Identification of UB mutants capable of E1 charging but blocked in E2-to-E3 transfer [20]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Studying Ubiquitin Chain Specificity

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features | Utility in Specificity Studies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chain-specific TUBEs | Affinity capture of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chains | Nanomolar affinity; linkage-selective (K48, K63, etc.) | High-throughput assessment of endogenous protein ubiquitination linkages | [21] [23] |

| Linkage-specific antibodies | Immunodetection of specific ubiquitin linkages | Specifically recognizes K48, K63, or other linkages | Western blot analysis of chain topology in in vitro and cellular assays | [21] |

| E2/E3 enzyme libraries | Comprehensive sets of purified enzymes | Tagged for purification; catalytic activity verified | Systematic pairing studies to determine combinatorial specificity | [17] [18] |

| Ubiquitin variant phage libraries | Profiling enzyme specificity | Randomized C-terminal sequences; high diversity | Mapping specificity determinants in E1 and E2 enzymes | [20] |

| Activity-based probes | Monitoring enzyme activities in complex mixtures | Specific for DUBs or other ubiquitin-system enzymes | Assessing oppositional activities that might influence net ubiquitination | [20] |

Visualization of the Specificity Determination Pathway

The hierarchical organization of the ubiquitin system—with E3 ligases acting as master regulators of specificity built upon the foundational activities of E1 and E2 enzymes—ensures precise control over ubiquitin chain formation. While E2 enzymes contribute intrinsic linkage preferences, E3 ligases ultimately dictate the topology of polyubiquitin chains and the specific lysine residues modified on substrate proteins. This sophisticated regulatory architecture enables the diversification of ubiquitin signals from a limited set of components, allowing precise control over countless cellular processes. The experimental frameworks and tools described herein provide researchers with robust methodologies for dissecting these specificity mechanisms, with significant implications for understanding disease pathogenesis and developing targeted therapeutic interventions, particularly in the expanding field of targeted protein degradation.

Ubiquitination is a fundamental post-translational modification that regulates virtually all eukaryotic cellular processes. The conventional understanding of ubiquitin signaling has been dominated by two canonical chain types: K48-linked chains targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, and K63-linked chains regulating non-proteolytic functions such as DNA repair and inflammation [24] [25]. However, recent research has unveiled a vastly more complex ubiquitin code encompassing diverse non-canonical linkages and branched chain architectures that significantly expand the functional repertoire of ubiquitin signaling.

The ubiquitin system's complexity operates at multiple levels. First, ubiquitin can be conjugated to substrate proteins not only on lysine residues but also on serine, threonine, cysteine, and the N-terminal methionine, a phenomenon termed non-canonical ubiquitination [24] [25]. Second, beyond homogeneous chains, ubiquitin can form heterotypic chains including mixed linkage chains (alternating linkage types) and branched chains where a single ubiquitin molecule serves as a branching point for multiple chains [2] [26]. This review examines the biological functions of these complex ubiquitin signals and provides detailed methodologies for their study in vitro, addressing a critical need in the field of ubiquitin research.

Table 1: Levels of Complexity in the Ubiquitin Code

| Complexity Level | Description | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Diversity | >9,000 known substrate proteins with >60,000 modification sites [25] | Specific modification sites can affect substrate structure and function |

| Linkage Types | 8 primary linkages (M1, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) plus non-canonical S/T/C linkages [25] | Distinct chain conformations create unique binding surfaces |

| Ubiquitin Modifications | Ubiquitin itself can be modified by phosphorylation, acetylation, ADP-ribosylation [25] | Fine-tunes ubiquitin signaling and recognition |

| Chain Architecture | Homotypic, mixed, and branched chains with varying lengths [25] [2] | Higher-order structures determine specific functional outcomes |

Quantitative Landscape of Non-Canonical and Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Recent advances in mass spectrometry and linkage-specific antibodies have enabled quantitative assessment of various ubiquitin chain types in cellular environments. While K48 and K63 linkages remain the most abundant, non-canonical and branched chains constitute a significant portion of the cellular ubiquitome. Quantitative analyses reveal that branched ubiquitin chains account for approximately 10-20% of total cellular polyubiquitin [27], highlighting their substantial contribution to ubiquitin signaling.

The functional significance of these chains is underscored by their specific association with critical cellular processes. For instance, K11/K48 branched chains have been identified as key regulators of cell cycle progression, particularly during mitosis [2] [26]. K29/K48 branched chains mediate proteasomal degradation in the ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway, while K48/K63 branched chains serve multiple functions including NF-κB signaling and as priority signals for p97/VCP processing [26].

Table 2: Biologically Characterized Branched Ubiquitin Chains

| Chain Type | Synthetic Enzymes | Biological Functions | Recognition/Disassembly Machinery |

|---|---|---|---|

| K11/K48 | APC/C (with UBE2C/UBE2S), UBR5 [2] [28] | Cell cycle regulation, protein degradation [26] | Proteasome recognition, enhanced degradation |

| K29/K48 | Ufd4/Ufd2 collaboration [2] [28] | Ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway [26] | Proteasomal targeting |

| K48/K63 | TRAF6/HUWE1, ITCH/UBR5 collaboration [2] | NF-κB signaling, apoptosis, p97/VCP processing [26] | UCH37 debranching, proteasomal degradation |

| K6/K48 | Parkin, NleL [2] [28] | Mitophagy, protein degradation | UCH37/RPN13 complex [27] |

Experimental Protocol 1: Enzymatic Assembly of Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Principle

This protocol enables the synthesis of defined branched ubiquitin trimers through sequential enzymatic ligation using linkage-specific E2 enzymes and ubiquitin mutants. The method utilizes C-terminally blocked proximal ubiquitin to control chain elongation directionality, allowing systematic construction of various branched architectures [26].

Materials

- Ubiquitin mutants: Ub1-76 (wild-type), Ub1-72 (C-terminally truncated), UbK48R, UbK63R, UbK48R,K63R

- E2 enzymes: UBE2N/UBE2V1 (K63-specific), UBE2R1 or UBE2K (K48-specific)

- Reaction buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 5 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT

- E1 enzyme: Commercially available ubiquitin-activating enzyme

- Purification equipment: FPLC system with size-exclusion and ion-exchange columns

Step-by-Step Procedure

Prepare proximal ubiquitin: Use Ub1-72 or ubiquitin with C-terminal modifications (UbD77 or Ub6his) to prevent elongation at the C-terminus [26].

First ligation - K63 chain formation:

- Set up reaction mixture: 100 μM Ub1-72, 150 μM UbK48R,K63R, 100 nM E1, 1 μM UBE2N/UBE2V1 complex in reaction buffer

- Incubate at 30°C for 2 hours

- Purify K63-linked dimer using size-exclusion chromatography

Second ligation - K48 branch formation:

- Set up reaction mixture: 50 μM K63-dimer from step 2, 100 μM UbK48R,K63R, 100 nM E1, 1 μM UBE2R1 or UBE2K in reaction buffer

- Incubate at 30°C for 2 hours

- Purify branched trimer using ion-exchange chromatography

Quality control:

- Verify chain architecture by mass spectrometry

- Confirm linkage specificity using linkage-specific deubiquitinases

- Assess functionality through binding assays with ubiquitin-binding domains

Critical Notes

- Enzyme-to-substrate ratios should be optimized for each E2 enzyme combination

- The order of ligation steps can be reversed to create alternative branching patterns

- For more complex tetrameric structures, implement the Ub-capping approach using OTULIN to remove C-terminal blocks after initial branch formation [26]

Experimental Protocol 2: Chemical Synthesis of Non-Canonical Ubiquitin Chains

Principle

Chemical synthesis provides precise control over ubiquitin chain architecture, enabling incorporation of non-canonical linkages, specific mutations, and chemical tags that are challenging to achieve through enzymatic methods. This protocol utilizes native chemical ligation (NCL) of solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS)-generated fragments to produce ubiquitin chains with defined linkages [26].

Materials

- SPPS equipment: Automated peptide synthesizer

- Ubiquitin building blocks: SPPS-generated ubiquitin fragments (1-45 and 46-76) with appropriate protecting groups

- Ligation reagents: MPAA (4-mercaptophenylacetic acid), TCEP, thiophenol

- IsoUb core: Pre-formed isopeptide-linked ubiquitin core for branched chain synthesis

- Purification system: HPLC with C18 reverse-phase column

Step-by-Step Procedure

Synthesize ubiquitin fragments:

- Perform SPPS of ubiquitin fragments 1-45 and 46-76 with N-terminal cysteine and C-terminal thioester, respectively

- Incorporate desired mutations at specific positions for linkage control

Native chemical ligation:

- Dissolve ubiquitin fragments in ligation buffer (6 M guanidine-HCl, 0.1 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.0)

- Add MPAA (50 mM) and TCEP (20 mM) as catalysts

- Incubate at 37°C for 12-16 hours with gentle agitation

- Monitor reaction progress by analytical HPLC

Folding and purification:

- Dilute ligation product into folding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol)

- Incubate at 4°C for 24 hours

- Purify folded ubiquitin chain by reverse-phase HPLC

- Verify correct folding by circular dichroism spectroscopy

Branched chain assembly:

- For branched chains, utilize pre-formed "isoUb" core strategy with residues 46-76 of distal ubiquitin linked via isopeptide bond to residues 1-45 of proximal ubiquitin [26]

- Perform sequential NCL to extend branches as needed

Critical Notes

- Maintain reducing conditions throughout to prevent disulfide formation

- Optimize ligation times for different ubiquitin constructs

- Verify correct isopeptide bond formation by mass spectrometry and linkage-specific antibodies

Biological Functions and Applications in Targeted Protein Degradation

The discovery of non-canonical and branched ubiquitin chains has profound implications for understanding cellular regulation and developing novel therapeutic strategies. Branched ubiquitin chains, particularly those containing K48 linkages, function as potent degradation signals that enhance substrate targeting to the proteasome [2] [28]. This property is being exploited in the emerging field of targeted protein degradation, where heterobifunctional molecules such as PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras) recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases to neosubstrates, inducing their ubiquitination and degradation [25].

Recent studies demonstrate that PROTAC-induced degradation involves the formation of complex ubiquitin chains, including branched architectures. For example, the PROTAC-induced degradation of BRD4 involves sequential activity of CRL2VHL and TRIP12 E3 ligases, resulting in the formation of branched K29/K48 chains that enhance degradation efficiency [28]. The formation of stable neosubstrate-PROTAC-E3 ternary complexes is critical for degradation, with K48-specific E2s UBE2G and UBE2R1 required for this process [25].

The debranching enzyme UCH37, which associates with the 26S proteasome, plays a critical role in processing branched ubiquitin chains during substrate degradation. UCH37 shows remarkable specificity for branched chains, with strong preference for K6/K48 over K11/K48 or K48/K63 branched architectures [27]. This debranching activity facilitates proteasomal clearance of stress-induced inclusions and promotes recycling of the proteasome for subsequent rounds of substrate processing [27].

Figure 1: PROTAC-Induced Protein Degradation via Branched Ubiquitin Chains. Heterobifunctional PROTAC molecules bridge E3 ubiquitin ligases and target proteins, leading to sequential assembly of K48-linked and branched K29/K48 chains that enhance proteasomal targeting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Non-Canonical and Branched Ubiquitin Chains

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E2 Enzymes | UBE2N/UBE2V1 (K63), UBE2R1 (K48), UBE2C (K11), UBE2S (K11) | Linkage-specific chain assembly in vitro | Define linkage specificity in chain formation |

| E3 Ligases | APC/C (K11/K48), TRAF6 (K63), HUWE1 (K48), UBR5 (K48/K63) | Substrate recognition and chain elongation | Some exhibit inherent branching capability |

| DUBs | OTULIN (M1), UCH37 (branched K48), ataxin-3 (mixed chains) | Linkage-specific chain disassembly | Analytical tools for chain validation |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | UbK0 (all lysines mutated), Ub1-72 (C-terminal truncation) | Controlled chain assembly | Prevent non-specific elongation |

| Chemical Tools | PROTACs, molecular glues, activity-based probes | Induce targeted degradation, monitor activity | Enable pharmacological manipulation |

| Detection Reagents | Linkage-specific antibodies, UBD probes, mass spectrometry standards | Identify and quantify specific chain types | TUBE assays for ubiquitin enrichment |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The expanding landscape of non-canonical and branched ubiquitin chains represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of ubiquitin signaling. These complex ubiquitin architectures provide cells with sophisticated regulatory mechanisms to fine-tune protein functions, localization, and stability under varying physiological conditions. The development of novel methodologies to synthesize and analyze these chains, as detailed in this review, will accelerate our understanding of their biological functions and therapeutic potential.

Future research directions will likely focus on elucidating the complete spectrum of branched chain architectures present in cells, developing more sophisticated tools for their study, and harnessing this knowledge for therapeutic applications, particularly in the field of targeted protein degradation. As our toolkit for studying these complex signals expands, so too will our ability to decipher the intricate language of the ubiquitin code and manipulate it for therapeutic benefit.

Synthesizing Defined Polyubiquitin Chains: Enzymatic, Chemical, and Hybrid Assembly Strategies

The post-translational modification of proteins with ubiquitin chains is a fundamental regulatory mechanism that governs nearly all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology, with specific chain architectures encoding distinct functional outcomes [18]. The enzymatic assembly of these chains is mediated by a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes, where E2-E3 pairs serve as the crucial determinants of linkage specificity and chain topology [29] [18] [30]. Homotypic chains, in which all ubiquitin subunits are connected through the same linkage type (e.g., K48-linked chains that typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation), represent the best-characterized class of ubiquitin polymers [19] [1]. In contrast, branched ubiquitin chains are complex architectures where at least one ubiquitin moiety within the chain is modified at two or more distinct sites simultaneously, creating bifurcation points that significantly expand the signaling capacity of the ubiquitin system [26] [5]. These branched conjugates constitute a substantial fraction of the cellular polyubiquitin pool and play essential roles in diverse processes ranging from enhanced proteasomal targeting to the organization of large signaling complexes [26] [1] [5].

This application note provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers aiming to reconstitute both homotypic and branched ubiquitin chains in vitro. We detail specific E2-E3 pairing strategies, synthesize quantitative kinetic data into comparable formats, and provide validated experimental protocols to support investigations into the structural and functional biology of polyubiquitin chain formation.

Core Concepts: E2-E3 Pairing Specificity and Chain Assembly Mechanisms

Determinants of E2-E3 Pairing Specificity

The specific partnership between E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases forms the foundation of ubiquitin chain assembly. This pairing is governed by multiple tiers of selectivity:

- Domain-Specific Interactions: The E2-docking domain of the E3 (e.g., RING, U-box) provides the initial interaction surface, but additional domains (e.g., armadillo repeats in PUB22) can impose further specificity, restricting interaction to a subset of E2s [29].

- Dynamic Regulation: E2-E3 partnerships are not static; they can be modulated by cellular signals. During immune responses in plants, PUB22 pairing with group VI UBC30 is inhibited while interaction with the K63 chain-building UBC35 is enhanced [29].

- Functional Specialization: E2s often specialize in specific aspects of chain formation. Cdc34/UBE2R-family E2s, for instance, are specialized for Lys48-linked chain extension on CRL substrates, achieving millisecond kinetics [31].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Chain Assembly

E2-E3 pairs utilize distinct mechanistic strategies to build ubiquitin chains:

- Sequential Addition: Ubiquitin molecules are added one at a time to the growing chain, with the E2-E3 complex catalyzing each addition [18].

- En Bloc Transfer: Pre-assembled ubiquitin chains are transferred to substrates in a single step [18].

- Collaborative Assembly: Distinct E2-E3 pairs work sequentially, with one handling chain initiation and another specializing in chain elongation [18].

- Branching Mechanisms: Branched chains can be formed through collaboration between different E2s with a single E3, sequential action of distinct E3s with different linkage specificities, or the intrinsic activity of certain E2s like UBE2K [1] [5].

The following diagram illustrates the core enzymatic workflow for ubiquitin chain assembly, highlighting the decision points between homotypic and branched chain synthesis:

Diagram Title: Enzymatic Workflow for Ubiquitin Chain Assembly

Homotypic Chain Assembly: Strategies and Protocols

Cullin-RING Ligases with UBE2R Family E2s for K48-Linked Chains

Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) in partnership with UBE2R-family E2s (Cdc34/UBE2R) represent the principal cellular machinery for assembling K48-linked ubiquitin chains that target substrates for proteasomal degradation [31]. Recent structural insights from cryo-EM studies reveal how neddylated CRLs activate UBE2R2~ubiquitin for millisecond chain formation, positioning both the donor ubiquitin and the acceptor ubiquitin-linked substrate within the active site for efficient catalysis [31].

Protocol: In Vitro Reconstitution of K48-Linked Polyubiquitination using CRL2FEM1C and UBE2R2

Materials Required:

- Neddylated CRL2FEM1C complex (CUL2-RBX1-NEDD8 + Elongin B/C-FEM1C)

- UBE2R2 (human, residues 1-187, C93A catalytic mutant for structural studies)

- E1 activating enzyme (UBA1)

- Ubiquitin (wild-type and K48-only mutant)

- Target substrate with C-terminal degron (e.g., Sil1 peptide)

- Reaction buffer: 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 mM TCEP

- ATP regeneration system: 2 mM ATP, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 0.1 μg/μL creatine kinase

Procedure:

- Prepare Reaction Mixture: Combine in reaction buffer:

- 50 nM neddylated CRL2FEM1C

- 2 μM UBE2R2

- 100 nM E1 (UBA1)

- 200 μM ubiquitin (K48-only mutant preferred for linkage specificity)

- 5 μM substrate peptide

- ATP regeneration system

Initiate Reaction: Add ATP to final concentration of 2 mM to initiate the ubiquitination cascade.

Incubate: Maintain reaction at 30°C for desired timepoints (typically 5-60 minutes).

Terminate and Analyze: Stop reaction by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer with 50 mM DTT. Analyze by:

- Immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin and substrate-specific antibodies

- Mass spectrometry to verify K48 linkage specificity

- Gel densitometry for kinetic analysis

Key Considerations:

- NEDD8 modification of the cullin subunit is essential for maximal activity, reducing the Km of UBE2R2 for ubiquitin chain extension [31].

- The acidic C-terminal tail of UBE2R2 dynamically interacts with a basic canyon on cullins, enhancing closed conformation formation with donor ubiquitin [31].

- For structural studies, use crosslinking strategies to trap transient polyubiquitylation intermediates as described in [31].

Quantitative Analysis of Homotypic Chain Assembly Systems

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of E2-E3 Systems for Homotypic Chain Assembly

| E2-E3 Pair | Linkage Type | Assembly Mechanism | Kinetic Parameters | Key Structural Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2R2/CRL2FEM1C [31] | K48 | Sequential addition | Millisecond timescale for chain extension; NEDD8 activation reduces Km | UBE2R2 loop rearrangement by RING; NEDD8 releases RING from CRL | Proteasomal targeting studies; Substrate degradation kinetics |

| UBE2N-UBE2V1/RING E3s [26] [18] | K63 | Sequential addition | Processive chain formation | E2 heterodimer with UBE2V1 enhancing specificity | DNA repair signaling; NF-κB pathway reconstitution |

| UBE2S/APC/C [18] [5] | K11 | Sequential addition | Distinct E2s for initiation (UBE2C) and elongation (UBE2S) | E2-ubiquitin closed conformation stabilized by E3 | Cell cycle regulation; Anaphase-promoting complex studies |

| UBE2L3/HOIP [32] | M1 (linear) | Sequential addition | RBR E3 mechanism with E2~Ub charging E3 intermediate | Triple RING hybrid architecture; specific for M1 linkage | NF-κB signaling complex assembly; LUBAC signaling studies |

Branched Chain Assembly: Strategies and Protocols

Mechanisms and Enzyme Systems for Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Branched ubiquitin chains expand the topological complexity of ubiquitin signaling by incorporating multiple linkage types within a single polymer [26] [5]. Three major mechanistic paradigms have been identified for branched chain assembly:

Single E3 with Multiple E2s: The anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) collaborates sequentially with UBE2C (initiation) and UBE2S (elongation) to produce K11/K48-branched chains on cell cycle regulators like cyclin B [1] [5].

Collaborating E3 Pairs: The HECT E3s ITCH and UBR5 cooperate to assemble K48/K63-branched chains on TXNIP, with ITCH building K63 chains that UBR5 then decorates with K48 branches [1].

Intrinsic E2 Branching Activity: Yeast Ubc1 and its mammalian ortholog UBE2K promote assembly of K48/K63-branched chains through their inherent catalytic properties [1].

The following diagram illustrates the three primary mechanisms for assembling branched ubiquitin chains:

Diagram Title: Three Mechanisms for Branched Ubiquitin Chain Assembly

Protocol: Enzymatic Assembly of K48-K63 Branched Ubiquitin Trimers

This protocol adapts methodologies from recent studies to generate defined branched ubiquitin trimers using a combination of linkage-specific enzymes and ubiquitin mutants [26] [1].

Materials Required:

- E1 activating enzyme (UBA1)

- E2 enzymes: UBE2N-UBE2V1 complex (K63-specific), UBE2R1 or UBE2K (K48-specific)

- Proximal ubiquitin mutant (Ub1-72 or UbD77)

- Distal ubiquitin mutant (UbK48R,K63R)

- Reaction buffers: As in homotypic protocol with optimization for each E2

- Purification columns for chain isolation

Procedure:

- Prepare K63-Linked Dimer:

- Combine 100 μM Ub1-72 (proximal, C-terminally truncated), 200 μM UbK48R,K63R (distal mutant)

- Add 100 nM E1, 2 μM UBE2N-UBE2V1 complex, ATP regeneration system

- Incubate 60 minutes at 30°C

- Purify K63 dimer using size exclusion chromatography

Assemble K48 Branch:

- Combine purified K63 dimer with 200 μM UbK48R,K63R

- Add 100 nM E1, 2 μM UBE2R1 (K48-specific), ATP regeneration system

- Incubate 60 minutes at 30°C

- Purify branched trimer using ion exchange chromatography

Verification and Quality Control:

- Confirm branched architecture by middle-down mass spectrometry [5]

- Verify linkage specificity using linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs)

- Assess chain length and purity by SDS-PAGE and anti-ubiquitin immunoblotting

Alternative Method: Ub-Capping Approach for Extended Branched Chains For more complex tetrameric branched structures, employ a Ub-capping strategy using the yeast DUB Yuh1 to trim the C-terminus of a D77-blocked ubiquitin, exposing the native C-terminus for further chain extension [26].

Advanced Methods: Chemical and Synthetic Biology Approaches

Beyond enzymatic assembly, several advanced methodologies enable precise construction of branched ubiquitin chains:

Chemical Synthesis: Full chemical synthesis via native chemical ligation (NCL) enables incorporation of non-native modifications and generates DUB-resistant chains [26]. The 'isoUb' core strategy links residues 46-76 of distal ubiquitin to residues 1-45 of proximal ubiquitin via a pre-formed isopeptide bond [26].

Genetic Code Expansion: Site-specific incorporation of noncanonical amino acids through amber stop codon suppression allows protection/deprotection strategies for controlled branched chain assembly [26]. This approach has been used to synthesize K11-K33 branched trimers.

Photo-controlled Assembly: Utilizes ubiquitin moieties with lysine residues protected by photolabile 6-nitroveratryloxycarbonyl (NVOC) groups, enabling sequential linkage formation through alternating UV deprotection and enzymatic elongation cycles [26].

Quantitative Analysis of Branched Chain Assembly Systems

Table 2: Characterized E2-E3 Systems for Branched Ubiquitin Chain Assembly

| E2-E3 System | Branched Linkage | Assembly Mechanism | Functional Outcome | Validated Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC/C + UBE2C + UBE2S [1] [5] | K11/K48 | Sequential E2 action with single E3 | Enhanced proteasomal degradation | Cyclin B, NEK2A, Histone H2B |

| cIAP1 + UBE2D + UBE2N/UBE2V [1] | K48/K63, K11/K48 | Sequential E2 action with single E3 | Proteasomal degradation (chemically induced) | cIAP1, ER-α |

| ITCH + UBR5 [1] | K48/K63 | Collaborating E3 pairs | Proteasomal degradation | TXNIP |

| Ufd4 + Ufd2 [1] | K29/K48 | Collaborating E3 pairs | Proteasomal degradation (ERAD) | Ub-V-GFP (model substrate) |

| Ubc1/UBE2K [1] | K48/K63 | Intrinsic E2 branching activity | Unknown cellular function | In vitro model substrates |

| Parkin [1] | K6/K48 | Single E3 with intrinsic branching | Unknown (in vitro) | Model substrates |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Chain Assembly Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| E2 Enzymes | UBE2R2 (Cdc34 homolog) | K48-linked chain extension with CRLs | Acidic C-terminal tail; millisecond kinetics [31] |

| UBE2N-UBE2V1 heterodimer | K63-linked chain formation | Heterodimeric complex; NF-κB signaling [26] | |

| UBE2S | K11-linked chain elongation with APC/C | Specialized for chain elongation [5] | |

| E3 Ligases | CRL family (CUL1-RBX1, CUL2-RBX1) | Modular substrate recognition | NEDD8 activation required; ~300 human variants [31] |

| APC/C (Multi-subunit) | Cell cycle regulation | Forms K11/K48 branched chains [1] [5] | |

| HECT E3s (NleL, UBE3C) | Branched chain formation | Forms E3~Ub intermediate; linkage determination [1] | |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | UbK48R, UbK63R | Linkage specificity control | Prevents specific linkages; essential for defined chain synthesis [26] |

| Ub1-72 (C-terminal truncation) | Chain assembly block | Prevents chain extension; useful for trimer synthesis [26] | |

| UbD77 | C-terminal blocking | Alternative to truncation mutants [26] | |

| Specialized Tools | Linkage-specific DUBs | Chain verification and editing | Cleave specific linkages (e.g., OTULIN for M1) [26] [5] |

| NEDD8-activating enzyme | CRL activation | Essential for full CRL activity [31] | |

| Ubiquitin vinyl sulfones | DUB activity profiling | Activity-based probes for deubiquitinases [26] |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Optimization Strategies for Efficient Chain Assembly

E2-E3 Stoichiometry: Systematic titration of E2:E3 ratios is critical. For UBE2R2 with CRLs, optimal activity typically occurs at 10-40:1 molar ratios of E2:E3 [31].

NEDD8 Activation: Ensure complete neddylation of cullin-based E3s through pre-incubation with NEDD8-E1-E2 enzymes or using pre-neddylated complexes [31].

Ubiquitin Mutant Validation: Verify that ubiquitin point mutants (e.g., K-to-R) truly prevent specific linkages through control reactions with linkage-specific DUBs [26].

Temporal Control: For branched chains requiring sequential E2 actions, optimize incubation times for each step to prevent incomplete intermediate formation [26] [1].

Analytical Validation of Chain Architecture

Middle-Down Mass Spectrometry: Provides unambiguous identification of branched chain topology and linkage composition [5].

Linkage-Specific DUB Profiling: Use panels of DUBs with known linkage preferences (e.g., OTULIN for M1, Cezanne for K11) to verify chain architecture [26] [5].

Antibody-Based Detection: Employ linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., K48-linkage specific) for initial screening, though cross-reactivity limitations should be considered [26].

The strategic pairing of E2 conjugating enzymes with E3 ligases enables the controlled synthesis of both homotypic and branched ubiquitin chains in vitro, providing powerful tools for deciphering the ubiquitin code. As the field advances, emerging technologies including chemical biology approaches, genetic code expansion, and engineered E3 systems like the Ubiquiton platform [32] will further enhance our ability to construct defined ubiquitin architectures. These methodologies not only facilitate basic research into ubiquitin signaling mechanisms but also support drug discovery efforts targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system, particularly in areas such as targeted protein degradation where branched chains have been shown to enhance degradation efficiency [1] [5].

The study of polyubiquitin chain formation is fundamental to understanding diverse cellular processes, ranging from protein degradation to cell signaling and DNA repair. The ubiquitin code—the concept that different ubiquitin chain topographies encode distinct functional outcomes—presents a significant challenge for researchers. Native Chemical Ligation (NCL) and Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) have emerged as indispensable techniques for generating homogeneous ubiquitin conjugates with atomic-level precision, enabling detailed mechanistic studies that are challenging with traditional enzymatic approaches [33]. These chemical methods provide researchers with the ability to engineer ubiquitin chains with defined linkage types, specific lengths, and site-specific modifications, thus offering unparalleled control for deciphering the ubiquitin code.

The limitation of enzymatic methods primarily stems from the requirement for specific ubiquitin ligases (E3 enzymes) for given chain linkages and target proteins, coupled with generally low catalytic efficiency [34]. Furthermore, the study of non-traditional ubiquitin architectures, particularly branched ubiquitin chains, has been hampered by limited knowledge of the cellular enzymes responsible for their assembly [26]. Chemical synthesis bypasses these limitations, allowing for the production of homotypic chains, branched chains, and chains incorporating non-canonical amino acids or specific tags for biochemical and biophysical studies. This application note details standardized protocols for employing SPPS and NCL in polyubiquitin research, providing researchers with robust methodologies to advance their investigations.

Key Chemical Methodologies and Applications

Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) for Ubiquitin Building Blocks

Fmoc-based SPPS serves as the cornerstone for generating ubiquitin-derived peptides and protein fragments. This method relies on iterative cycles of deprotection and coupling to build polypeptides anchored to an insoluble resin [35] [34].

Core Principles and Mechanism

The Fmoc (fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl) group protects the α-amino group during synthesis. This protecting group is base-labile and stable to acid, allowing for orthogonal deprotection strategies alongside acid-labile side-chain protecting groups. The synthesis proceeds through cycles of Fmoc deprotection followed by coupling of the next Fmoc-amino acid [35].

Table: Key Reagents for Fmoc-SPPS

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Nα-Protecting Group | Fmoc (9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl) | Protects α-amino group during chain elongation; removed with base |

| Deprotection Reagent | Piperidine/DMF (1:4 v/v) | Removes Fmoc group via base-induced β-elimination |

| Coupling Reagents | DIC (Diisopropylcarbodiimide), HATU | Activates carboxylic acid for amide bond formation |

| Additives | HOBt (Hydroxybenzotriazole), HOAt | Suppresses racemization and enhances coupling efficiency |

| Solid Support | Polystyrene or PEG-based resins | Provides anchor for growing peptide chain |

- Prewash: Wash the peptide-resin with DMF (2 × 1 minute).

- Deprotection: Treat the resin with piperidine/DMF (1:4 v/v) using 10 mL of reagent per gram of peptide-resin.

- First treatment: 5 minutes.

- Second treatment: 10 minutes.

- Washing: Wash the resin alternately with DMF and isopropanol (IPA) until the effluent reaches neutral pH.

- Coupling: Proceed with the next coupling reaction using an activated Fmoc-amino acid derivative.

- Prepare Reagents: Use a molar ratio of 1:3:3 (free amino function : Fmoc-amino acid : DIC : HOBt).

- Activation: Dissolve the protected Fmoc-amino acid and HOBt in DMF or a DCM/DMF mixture. Add DIC and stir the reaction mixture at room temperature for 15-20 minutes.

- Coupling: Add the activated ester solution to the resin and allow the coupling to proceed with agitation. Monitor completion using quantitative color tests (e.g., Kaiser test).

- Post-Coupling: Wash the resin thoroughly with DMF after confirmed coupling completion.

Native Chemical Ligation (NCL) for Protein Assembly

NCL enables the chemoselective coupling of unprotected peptide segments to form native protein structures, making it ideal for synthesizing full-length ubiquitin and its conjugates [33].

Core Principles and Mechanism

NCL involves the reaction between a C-terminal peptide thioester and another peptide containing an N-terminal cysteine residue. The process proceeds through a reversible transthioesterification followed by an irreversible S→N acyl shift, resulting in a native peptide bond at the ligation site [33].

Diagram: Native Chemical Ligation Mechanism. The process involves two main steps leading to a native amide bond.

- Ligation Reaction Setup:

- Dissolve the peptide thioester and the N-terminal cysteine peptide in a suitable ligation buffer (e.g., 6 M Guanidine HCl, 0.1 M Sodium Phosphate, pH 7.0-7.5).

- Include 2-4% (v/v) of a thiol catalyst, such as mercaptophenylacetic acid (MPAA).

- Use equimolar amounts of each peptide, typically at concentrations of 1-5 mM.

- Reaction Execution:

- Incubate the reaction mixture at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Monitor reaction progress by analytical HPLC or LC-MS.

- The ligation is typically complete within 2-24 hours.

- Post-Ligation Processing:

- Quench the reaction by acidification (e.g., with TFA) or by diluting with cold ether.

- Purify the full-length product using reversed-phase HPLC.

- Optional Desulfurization:

- To convert cysteine to alanine at the ligation site, treat the ligated product with a desulfurization cocktail (e.g., VA-044 radical initiator with TCEP and glutathione in phosphate buffer, pH ~7) [33].

- This step expands the applicability of NCL to non-cysteine sites.

Synthesis of Branched Polyubiquitin Chains

Chemical methods are particularly powerful for constructing branched ubiquitin chains, which contain at least one ubiquitin moiety modified at two different lysine residues, creating a bifurcation point [36] [26].

This innovative strategy involves synthesizing a core unit where a fragment of the distal ubiquitin (e.g., residues 46-76) is linked via a pre-formed isopeptide bond to a fragment of the proximal ubiquitin (e.g., residues 1-45). This core contains an N-terminal cysteine and a C-terminal hydrazide, enabling efficient NCL for the attachment of additional ubiquitin building blocks to extend the chain.

This approach utilizes engineered E. coli to incorporate non-canonical amino acids with protected side chains (e.g., butoxycarbonyl-lysine, BOC-K) at specific lysine positions in ubiquitin via amber stop codon suppression. The protected lysines are subsequently deprotected, allowing for site-specific chemical ligation to assemble the branched trimer. This method can also be used with click chemistry to generate non-hydrolysable branched chains.

Diagram: Workflow for Branched Ubiquitin Chain Synthesis. The process integrates multiple chemical strategies to achieve complex architectures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The application of SPPS and NCL requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below catalogs essential items for successful implementation of these protocols.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Ubiquitin Synthesis

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Fmoc-Protected Amino Acids | Building blocks for SPPS | High purity, side-chain protecting groups (e.g., Pbf for Arg, trt for Asn/Gln/His) |

| HATU (Hexafluorophosphate Azabenzotriazole Tetramethyl Uronium) | Peptide coupling reagent | Potent activator, minimizes racemization, fast coupling kinetics [35] |

| MPAA (4-Mercaptophenylacetic Acid) | Catalyst for NCL | Aromatic thiol that enhances ligation kinetics and drives the reaction equilibrium [33] |

| TCEP (Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) | Reducing agent | Maintains cysteine residues in reduced state during NCL; prevents disulfide formation |

| VA-044 Radical Initiator | Desulfurization catalyst | Water-soluble azo compound that generates radicals for Cys-to-Ala conversion [33] |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs (e.g., OTUD1, Cezanne) | Validation tools | Cleave specific ubiquitin linkages to confirm chain topology (e.g., UbiCRest assay) [36] [37] |

| Photolabile NVOC Lysine | Orthogonal protection for branched chains | NVOC group (6-nitroveratryloxycarbonyl) is removed by UV light to control chain assembly [26] |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative analysis of synthesized ubiquitin chains is crucial for validation. Middle-down mass spectrometry techniques, such as UbiChEM-MS, are used to characterize chain architecture by analyzing proteolyzed fragments [36].

Table: UbiChEM-MS Signature Fragments for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

| Ubiquitin Fragment | Mass Signature | Represented Chain Topology |

|---|---|---|

| Ub~1-74~ | ~8.5 kDa | End-capped monoubiquitin |

| GG-Ub~1-74~ | ~8.6 kDa | Ubiquitin from a non-branched point in a chain |

| 2xGG-Ub~1-74~ | ~8.7 kDa | Branched ubiquitin (one ubiquitin modified at two sites) [36] |

Concluding Remarks

The chemical synthesis approaches of SPPS and NCL provide a powerful and versatile platform for interrogating the complex biology of the ubiquitin system. By enabling the production of homogeneous, defined polyubiquitin chains—including challenging architectures like branched chains—these methods allow researchers to move beyond the constraints of enzymatic synthesis. The detailed protocols and reagent toolkits outlined in this application note provide a solid foundation for in vitro research aimed at deciphering the ubiquitin code, with significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutics.

The study of polyubiquitin chain formation is fundamental to understanding critical cellular processes, including protein degradation, signal transduction, and DNA repair. The complexity of the ubiquitin code, comprising homotypic, mixed, and branched chains of various linkages, presents a significant challenge for in vitro research. Traditional methods for reconstituting these complex post-translational modifications have been limited by a lack of precision and temporal control. This application note details innovative hybrid techniques that merge genetic code expansion (GCE) with photo-controlled assembly to overcome these limitations. These methods enable the production of precisely defined, biologically relevant ubiquitin architectures with spatiotemporal resolution previously unattainable in biochemical studies. By providing protocols for synthesizing defined chain types and exploring branched ubiquitin structures, this framework empowers researchers to decipher the ubiquitin code with unprecedented accuracy [26] [38].

The integration of these technologies addresses a critical bottleneck in ubiquitin research: the controlled formation of specific polyubiquitin linkages and branched structures that are difficult to produce using conventional enzymatic methods. Genetic code expansion provides the foundation for incorporating photo-sensitive handles and non-canonical amino acids into ubiquitin monomers, while photo-controlled assembly offers a trigger for initiating specific chain formation with high precision. This combination is particularly valuable for studying the dynamics of ubiquitin chain assembly and disassembly, receptor activation mechanisms, and the functional consequences of specific ubiquitin modifications in signaling pathways [26] [39].

Technical Foundations and Integrated Workflow

Core Principle Integration