In Vivo vs. In Vitro Ubiquitination Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a detailed comparison of in vivo and in vitro ubiquitination detection techniques, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

In Vivo vs. In Vitro Ubiquitination Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of in vivo and in vitro ubiquitination detection techniques, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, explores established and emerging methodologies like immunoblotting and TUBE-based assays, and offers practical troubleshooting guidance. A critical validation framework is presented to help scientists select the optimal approach for their specific research context, whether studying fundamental biology or developing targeted protein degradation therapies like PROTACs.

Understanding the Ubiquitin Landscape: From Basic Biology to Technical Challenges

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is the primary pathway for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, a sophisticated mechanism essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis [1] [2]. This system regulates countless cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, gene expression, responses to oxidative stress, and the removal of damaged or misfolded proteins [2] [3]. The UPS operates through a two-step mechanism: first, proteins destined for degradation are covalently tagged with a ubiquitin chain; second, these tagged proteins are recognized and broken down by the proteasome complex [2]. The discovery of this system was so fundamentally important that it was acknowledged with the award of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose [2].

Central to the UPS is ubiquitin, a small, highly conserved protein of 76 amino acids that is universally expressed in eukaryotic cells [1] [4]. Ubiquitin serves as a molecular tag when attached to substrate proteins. This attachment occurs through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving three key enzyme classes: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3) [1] [4]. The specificity and diversity of ubiquitin signaling are further enhanced by the ability of ubiquitin itself to form polymers (polyubiquitin chains) through any of its seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or its N-terminal methionine (M1) [1] [4]. Different chain linkages create distinct molecular signals, with K48-linked chains being the primary signal for proteasomal degradation, while other linkages (e.g., K63-linked) often regulate non-proteolytic functions like DNA repair and protein trafficking [1] [4] [5].

The Enzymatic Cascade: E1, E2, and E3

The process of ubiquitination is mediated by a well-defined cascade of three enzymes that work in concert to attach ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins.

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzymes

The ubiquitination process initiates with the E1 enzyme, known as the ubiquitin-activating enzyme. The human genome encodes only a few E1 enzymes, highlighting their broad specificity [4] [6]. E1 catalyzes the ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin. This reaction forms a high-energy thioester bond between the C-terminal glycine (G76) of ubiquitin and a specific cysteine residue in the E1's active site [1] [4]. This initial activation step is ATP-dependent and commits ubiquitin to the conjugation pathway. As the first step in the cascade, E1 regulates all downstream ubiquitination, making it a potential point for therapeutic intervention [5].

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes

The activated ubiquitin is subsequently transferred from E1 to the active site cysteine of an E2 enzyme (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme), again via a thioester bond [1] [4]. The human genome encodes more E2s than E1s—over 35 distinct E2s—allowing for greater functional diversification [4] [6]. E2s are not merely passive carriers; they play a critical role in determining the type of ubiquitin chain that will be assembled. For instance, UBE2D3 is an E2 with promiscuous activity that supports the ubiquitination of diverse targets, including ribosomal proteins RPS10 and RPS20, thereby playing a role in protein quality control [7]. The E2 carries the charged ubiquitin to the final enzyme in the cascade, the E3 ligase.

E3: Ubiquitin Ligases

The E3 ubiquitin ligase is responsible for the paramount task of conferring substrate specificity. It simultaneously binds to the E2~ubiquitin complex and a specific target protein, facilitating the direct or indirect transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate [1] [4]. The human genome encodes a vast repertoire of over 600 E3 ligases, which are classified into several families based on their structure and mechanism [4] [6]. The major families include:

- RING (Really Interesting New Gene): These E3s act as scaffolds, bringing the E2~Ub and substrate into close proximity to facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer from the E2 to the substrate [4].

- HECT (Homologous to the E6AP C Terminus): These E3s form a transient thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [4].

- RBR (RING-Between-RING): These E3s employ a hybrid mechanism, combining aspects of both RING and HECT types [4].

This vast array of E3s allows the UPS to recognize and regulate an immense number of specific protein substrates with high precision.

Table 1: Core Enzymes of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Enzyme | Number in Humans | Primary Function | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | 2 [6] | Ubiquitin activation | ATP-dependent formation of E1~Ub thioester |

| E2 (Conjugating) | >35 [4] [6] | Ubiquitin carriage | Thioester-linked E2~Ub intermediate |

| E3 (Ligase) | >600 [4] [6] | Substrate recognition | Binds E2~Ub and substrate to facilitate transfer |

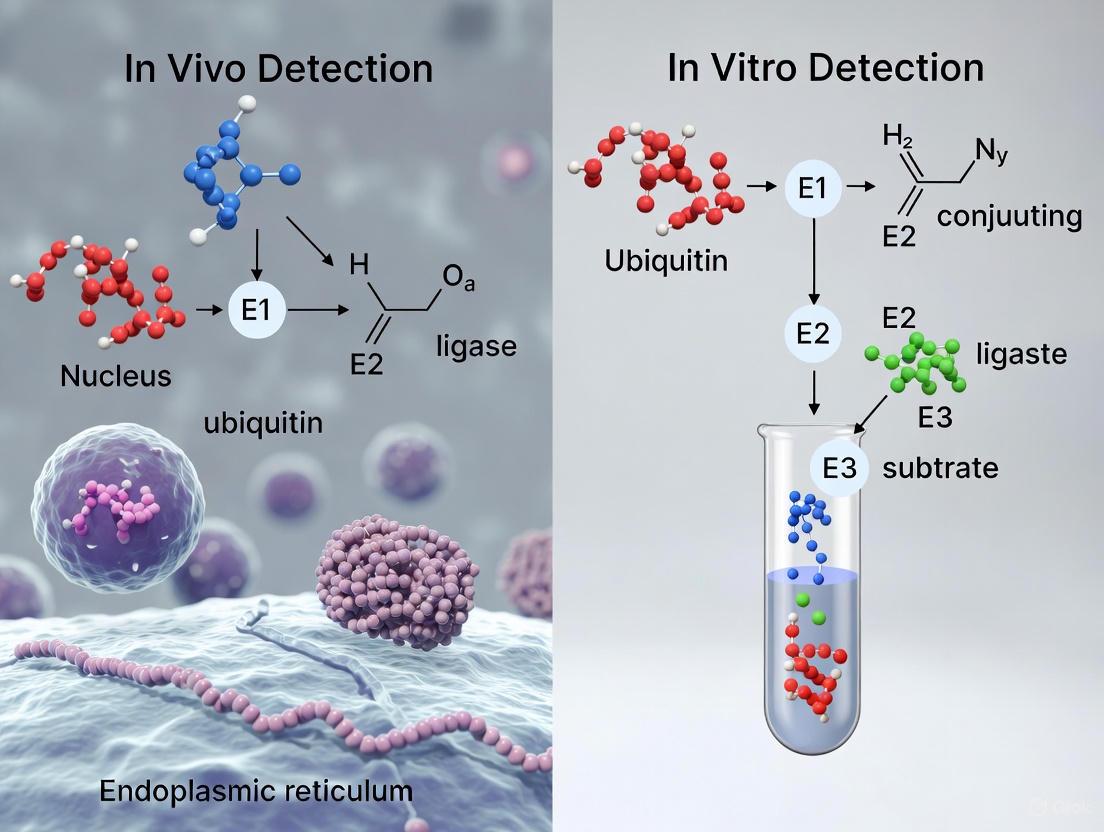

The following diagram illustrates the sequential actions of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes in the ubiquitination cascade:

The Proteasome: Structure and Function

The 26S proteasome is the terminal effector of the UPS, responsible for the actual degradation of ubiquitinated proteins. It is a massive, multi-subunit complex with a molecular mass of approximately 2000 kDa [2]. Its structure can be divided into two main components:

The 20S Core Particle (CP)

The 20S core particle is the catalytic heart of the proteasome. It is a barrel-shaped structure composed of four stacked heptameric rings [2] [3]. The two outer rings are made of seven α-subunits each, which function as a gated channel, controlling access to the interior. The two inner rings are composed of seven β-subunits each, which contain the proteolytic active sites. These sites exhibit three distinct cleavage specificities: chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and caspase-like activities, which work in concert to cleave substrate proteins into short peptides [2] [3].

The 19S Regulatory Particle (RP)

The 19S regulatory particle is a cap complex that associates with one or both ends of the 20S core to form the 26S proteasome. The 19S RP is responsible for several critical functions: it recognizes polyubiquitinated proteins, removes the ubiquitin tag for recycling via deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), unfolds the target protein in an ATP-dependent manner, and translocates the unfolded polypeptide into the 20S core for degradation [2] [3].

Specialized variants of the proteasome also exist, such as the immunoproteasome, which is induced by inflammatory signals and optimizes the generation of antigenic peptides for immune presentation [3].

Table 2: Proteasome Structure and Key Functions

| Component | Subunits | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|

| 20S Core Particle (CP) | 28 subunits (4 rings of 7) | Proteolytic degradation; contains trypsin-, chymotrypsin-, and caspase-like active sites [2] [3] |

| 19S Regulatory Particle (RP) | ~20 subunits (base and lid) | Substrate recognition, deubiquitination, unfolding, and translocation into the CP [2] [3] |

| Immunoproteasome | Alternative catalytic subunits | Enhanced production of peptides for MHC class I antigen presentation [3] |

Detection Techniques: In Vivo vs. In Vitro

Characterizing ubiquitination is challenging due to the dynamic nature of the modification, the low stoichiometry of modified proteins, and the complexity of polyubiquitin chains. A wide array of techniques has been developed, falling into two broad categories: in vivo (within living cells) and in vitro (in a controlled cell-free environment).

In Vivo Detection Techniques

In vivo methods aim to capture ubiquitination events within the context of a living cell, preserving physiological relevance.

- Tagged Ubiquitin Systems: A predominant strategy involves genetically engineering cells to express ubiquitin with an affinity tag (e.g., His, HA, or Strep). After lysis, ubiquitinated proteins can be purified en masse using the appropriate resin (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tags) and identified via mass spectrometry (MS) [6]. While powerful, this approach may introduce artifacts as the tagged ubiquitin does not perfectly mimic endogenous ubiquitin.

- Antibody-Based Enrichment: This method uses antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) to immunoprecipitate endogenously ubiquitinated proteins directly from cell or tissue lysates without genetic manipulation [6]. Linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., for K48 or K63 chains) can further delineate the type of ubiquitin chain present [6].

- Tandem-Repeated Ub-Binding Entities (TUBEs): TUBEs are engineered proteins with multiple ubiquitin-binding domains, which exhibit high affinity for polyubiquitin chains. They protect ubiquitinated substrates from deubiquitination and proteasomal degradation during lysis, improving the yield of labile ubiquitination events [6].

- Live-Cell Degradation Assays: Techniques like microinjection of fluorescently labeled substrates (e.g., GS-eGFP) followed by live-cell microscopy allow for direct measurement of real-time degradation kinetics in single cells, independent of biosynthesis or uptake variables [8].

In Vitro Detection Techniques

In vitro assays reconstruct the ubiquitination cascade using purified components, offering precise control over reaction conditions.

- Western Blot/Immunoblotting: The most conventional method, where reaction mixtures are probed with anti-ubiquitin antibodies to detect shifts in molecular weight indicative of ubiquitination [4] [6]. It is low-throughput but widely accessible.

- Fluorescence & Luminescence Assays: These include FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer), HTRF (Homogeneous Time-Resolved Fluorescence), and electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assays. They are amenable to high-throughput screening (HTS) for discovering ubiquitination regulators or inhibitors [4] [5].

- Reconstituted Ubiquitination Assays: These assays use purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ubiquitin, ATP, and a substrate to recapitulate the entire ubiquitination reaction in a test tube. This allows for detailed mechanistic studies of specific E2-E3 pairs [5].

The following workflow diagram compares the typical steps involved in these two methodological approaches:

Table 3: Comparison of Key Ubiquitination Detection Techniques

| Technique | Key Principle | Throughput | Physiological Context | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tagged Ub Pull-Down (in vivo) [6] | Affinity purification of Ub-conjugates from engineered cells | Medium | High (within living cells) | System-wide identification of ubiquitination sites (Ubiquitinome) |

| Antibody-Based IP (in vivo) [6] | Immunoprecipitation using anti-Ub antibodies | Low-Medium | High (native tissue possible) | Validation of substrate ubiquitination; linkage-specific studies |

| Live-Cell Microscopy (in vivo) [8] | Direct visualization of target protein degradation in single cells | Low | High (real-time kinetics) | Measuring precise degradation rates, catalytic efficiency of degraders |

| Reconstituted Assay (in vitro) [5] | Ubiquitination with purified components in a tube | Medium-High | Low (controlled reductionist system) | Mechanistic studies of enzyme activity; HTS for inhibitors |

| FRET/HTRF (in vitro) [5] | Fluorescent signal upon ubiquitination event | High | Low | High-throughput drug screening; kinetic studies |

A Practical Toolkit for UPS Research

To effectively study the UPS, researchers rely on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. Below is a non-exhaustive list of key solutions cited in the literature.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for UPS Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Tagged Ubiquitin (His, HA, Strep) [6] | Affinity-based purification of ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates. | Global ubiquitinome profiling via mass spectrometry [6]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies [6] | Detect or enrich for polyUb chains with a specific linkage (K48, K63, etc.). | Studying K48-linked tau ubiquitination in Alzheimer's disease [6]. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) [6] | High-affinity enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins; protect chains from DUBs. | Capturing and stabilizing low-abundance or labile ubiquitinated substrates. |

| Proteasome Activity Assay Kits [3] | Fluorescent-based measurement of proteasome's chymotrypsin-, trypsin-, or caspase-like activity. | Profiling proteasome function in cell lysates under different conditions (e.g., stress, inhibition). |

| Specific E3 Ligase Components (e.g., CHIPΔTPR) [8] | Serves as the recruitment module in bioPROTACs or for in vitro ubiquitination assays. | Targeted protein degradation of a proof-of-concept target like eGFP [8]. |

| Potent Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG-132, Lactacystin) [3] | Block the proteolytic activity of the proteasome, causing accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins. | Validating UPS-dependent degradation of a substrate; studying cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. |

Experimental Protocol: Key Methodologies

This section outlines detailed protocols for two pivotal experiments commonly used to investigate the UPS.

Protocol 1: In Vivo Global Ubiquitinome Profiling using Tagged Ubiquitin

This protocol is adapted from large-scale MS studies and is used to identify ubiquitination sites across the proteome [6] [7].

- Cell Line Engineering: Generate a cell line (e.g., HEK293T) that stably expresses 6xHis-tagged or Strep-tagged ubiquitin using lentiviral transduction or other stable expression methods.

- Cell Lysis and Denaturation: Harvest cells and lyse them in a denaturing buffer (e.g., 6 M Guanidine-HCl, 100 mM NaH₂PO₄, 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0) to inactivate DUBs and proteases, thereby preserving the ubiquitin-modified proteome.

- Affinity Purification: Incubate the clarified denatured lysate with the appropriate affinity resin:

- Elution and Digestion: Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins from the beads. A common method is to boil the beads in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Alternatively, proteins can be on-bead digested with trypsin for MS analysis.

- Mass Spectrometric Analysis: The digested peptides are analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Ubiquitination sites are identified by searching for the signature diGly remnant (a mass shift of +114.04 Da on the modified lysine) that remains after trypsin digestion of ubiquitinated proteins [6] [7].

- Data Analysis and Validation: Use bioinformatic tools to filter and validate the identified ubiquitination sites. Key hits are typically validated by orthogonal methods like immunoblotting.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

This protocol describes a foundational experiment to study the activity of a specific E2-E3 pair or the ubiquitination of a specific substrate in a controlled environment [5].

- Reagent Preparation: Purify or procure the required recombinant proteins: E1 enzyme, the E2 enzyme of interest (e.g., UBE2D3), the E3 ligase, the substrate protein, and ubiquitin.

- Reaction Setup: Assemble a 20-50 µL reaction mixture containing:

- Energy Regeneration System: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM ATP.

- Enzymes and Substrates: 100 nM E1, 1-5 µM E2, 1-5 µM E3, 5-10 µM Substrate protein, and 50-100 µM Ubiquitin.

- Negative Controls: Set up control reactions omitting E1, E2, E3, or ATP to confirm the specificity of the reaction.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 1-2 hours.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heating at 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Analysis by Immunoblotting:

- Resolve the proteins by SDS-PAGE.

- Transfer to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane.

- Probe the membrane with an antibody against your substrate to observe an upward gel shift (smearing) indicative of ubiquitination.

- Alternatively, probe with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (e.g., P4D1 or FK2) to directly visualize the ubiquitinated species.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, to target substrate proteins [4]. This modification serves as a versatile cellular signal that regulates diverse fundamental processes, including targeted protein degradation, cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, and numerous cell signaling pathways [4]. The complexity of ubiquitin signaling arises from its ability to form different types of conjugates—ranging from a single ubiquitin monomer (monoubiquitination) to complex polyubiquitin chains of various lengths and linkage types [6].

The specificity of ubiquitin signals is determined by an enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes [9]. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2 enzymes and over 600 E3 ligases, which provide remarkable specificity in substrate recognition [10]. This intricate system allows cells to generate precise ubiquitin signals that are decoded by effector proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains, ultimately leading to specific functional outcomes [10].

Understanding the distinction between monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination is fundamental to deciphering the ubiquitin code. While monoubiquitination typically regulates non-proteolytic processes such as endocytosis, histone modification, and DNA damage responses, different polyubiquitin chain linkages direct distinct cellular outcomes, with K48-linked chains primarily targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation [11]. Recent research has further revealed that ubiquitin chains can form complex branched architectures, adding another layer of complexity to this sophisticated signaling system [12].

Ubiquitin Signal Complexity: Structural and Functional Diversity

Monoubiquitination: Beyond a Simple Signal

Monoubiquitination, the attachment of a single ubiquitin moiety to a substrate, serves as a specific signal that differs functionally from polyubiquitin chains [10]. Contrary to initial assumptions, monoubiquitination is not merely a precursor to chain formation but represents a dedicated signaling event with distinct regulatory consequences. Monoubiquitinated proteins often function in regulatory roles rather than degradation targeting, influencing processes such as gene transcription, protein trafficking, and DNA repair mechanisms [10].

The generation of monoubiquitin signals requires specific cellular strategies to terminate the ubiquitination reaction after addition of a single ubiquitin moiety. Research has revealed several mechanisms that prevent chain elongation, including: (1) the substrate dissociation model, where fast dissociation rates of substrates from E3 enzymes prevent multiple ubiquitin transfers; (2) the self-inactivation model, where intramolecular interactions within monoubiquitinated proteins prevent further E3 binding; and (3) the E2 incompetent model, where specific E2 enzymes lack the capacity for chain extension [10]. These mechanisms ensure that monoubiquitination serves as an independent signal rather than an incomplete polyubiquitination event.

Polyubiquitin Chains: A Complex Language of Linkages

Polyubiquitin chains are classified based on their linkage patterns, which determine their three-dimensional structure and functional specificity [4]. The seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and the N-terminal methionine (M1) of ubiquitin can each form distinct chain linkages with unique functional consequences [4].

Table 1: Polyubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Cellular Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Targets substrates for proteasomal degradation [4] | Compact structure recognized by proteasomal receptors |

| K63-linked | Regulates protein-protein interactions, DNA repair, NF-κB signaling [4] [6] | More open, extended chain conformation |

| K11-linked | Cell cycle regulation, proteasomal degradation [4] | Shares structural similarities with K48-linked chains |

| K6-linked | DNA damage repair, mitochondrial autophagy [4] | Associated with DNA damage response pathways |

| K27-linked | Controls mitochondrial autophagy [4] | Implicated in mitophagy and cellular stress responses |

| K29-linked | Cell cycle regulation, RNA processing, stress response [4] | Less characterized but linked to neurodegenerative disorders |

| K33-linked | T-cell receptor-mediated signaling [4] | Regulates enzymatic activity in immune signaling |

| M1-linked | Regulates NF-κB inflammatory signaling [4] | Linear chains generated by LUBAC complex |

Branched Ubiquitin Chains: Expanding the Signaling Landscape

Beyond homotypic chains, ubiquitin can form heterotypic chains with mixed or branched architectures [12]. Branched chains contain at least one ubiquitin subunit modified simultaneously at two different acceptor sites, creating complex topological structures that significantly expand the ubiquitin signaling vocabulary [12]. For example, branched K11/K48 chains synthesized by the APC/C complex during mitosis combine the degradative signal of K48 linkages with the cell cycle regulatory function of K11 linkages, potentially enabling more precise control of substrate degradation timing [12].

The synthesis of branched chains often involves collaboration between E3 ligases with distinct linkage specificities. For instance, TRAF6 (which synthesizes K63-linked chains) and HUWE1 (a K48-linkage specialist) collaborate to form branched K48/K63 chains during NF-κB signaling [12]. Similarly, UBR5 recognizes K63-linked chains synthesized by ITCH and attaches K48 linkages to produce branched K48/K63 chains on the pro-apoptotic regulator TXNIP, converting a non-degradative signal into a proteasome-targeting signal [12].

Detection Methodologies: In Vivo vs. In Vitro Approaches

In Vivo Detection Techniques

In vivo ubiquitination detection methods aim to capture ubiquitination events within their native cellular context, preserving physiological enzyme concentrations, subcellular localization, and cellular compartmentalization.

Genetic Manipulation Approaches involve expressing tagged ubiquitin constructs (e.g., His-, Flag-, or HA-tagged ubiquitin) in cells, allowing affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins under denaturing conditions [6]. The Stable Tagged Ubiquitin Exchange (StUbEx) system enables replacement of endogenous ubiquitin with tagged variants, providing a more physiological approach [6]. These methods allow identification of ubiquitination sites through mass spectrometry analysis by detecting the characteristic 114.04 Da mass shift on modified lysine residues [6].

Proximity Labeling Techniques represent cutting-edge in vivo approaches that capture spatial organization of ubiquitination events. The proximal-ubiquitinome workflow combines APEX2-based proximity labeling with enrichment of ubiquitin remnant motifs (K-ε-GG), allowing spatially resolved detection of ubiquitination events within specific cellular microenvironments [13]. This method has been successfully applied to identify substrates of deubiquitinases like USP30 in their native mitochondrial context [13].

BioPROTAC Degradation Assays provide functional readouts of ubiquitination efficiency in living cells. Recently developed assays use microinjection of fluorescently labeled target proteins and bioPROTACs followed by live-cell microscopy to directly measure degradation kinetics, avoiding confounding factors like biosynthesis and transport variability [8]. This single-cell approach has revealed that bioPROTAC efficiency depends critically on the correct orientation of the ternary complex for target ubiquitination rather than just binding affinity [8].

In Vitro Detection Techniques

In vitro methods offer controlled experimental conditions for mechanistic studies of ubiquitination, enabling precise manipulation of individual components and reaction conditions.

Reconstituted Biochemical Assays use purified E1, E2, and E3 enzymes to study ubiquitination mechanisms in isolation. These systems allow systematic testing of individual enzyme contributions and linkage specificity [14]. For example, studies with HUWE1 demonstrated that certain small-molecule inhibitors are actually substrates that become ubiquitinated, revealing unexpected dimensions of E3 ligase specificity [14].

Western Blotting/Immunoblotting remains widely used for initial ubiquitination detection using ubiquitin-specific antibodies [4] [6]. While this method is accessible and cost-effective, it provides limited information about chain linkage and architecture [4].

Fluorescence and Chemiluminescence Assays offer higher sensitivity and quantitative capabilities for kinetic studies. These assays often use labeled ubiquitin or antibodies to monitor ubiquitination in real-time, enabling determination of kinetic parameters [4].

Nanopore Sensing Assays represent an emerging technology that shows promise for direct detection of ubiquitin chains and their linkages without labeling, potentially enabling analysis of chain architecture [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Ubiquitination Detection Techniques

| Technique | Key Features | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tagged Ubiquitin (in vivo) | Expression of epitope-tagged ubiquitin (His, HA, Flag) | Ubiquitinome profiling, site identification [6] | High-throughput capability, identification of modification sites | May not mimic endogenous ubiquitin, potential artifacts |

| Antibody-Based Enrichment (in vivo) | Use of ubiquitin-specific antibodies (P4D1, FK1/FK2) or linkage-specific antibodies | Endogenous ubiquitination profiling, tissue samples [6] | Works under physiological conditions, no genetic manipulation needed | High cost, non-specific binding, limited antibody specificity |

| Proximity Labeling (in vivo) | APEX2-mediated biotinylation near DUBs of interest | Mapping DUB substrates, spatial ubiquitinomics [13] | Captures microenvironment-specific ubiquitination, identifies direct substrates | Complex workflow, requires genetic engineering |

| Reconstituted Biochemical Assays (in vitro) | Purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes with ubiquitin | Mechanistic studies, enzyme specificity, inhibitor screening [14] | Controlled conditions, precise manipulation of components | May lack cellular context, potential over-simplification |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Recombinant proteins with multiple ubiquitin-binding domains | Stabilization of ubiquitin conjugates, proteomics [6] | Protects against DUBs, enhances purification efficiency | Requires recombinant protein production |

| BioPROTAC Kinetic Assays (in vivo) | Microinjection + live-cell microscopy | Degradation rate measurement, degrader optimization [8] | Direct kinetic measurements, single-cell resolution | Technically challenging, low throughput |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Proximal-Ubiquitinome Profiling for DUB Substrate Identification [13]:

- Generate cell lines expressing DUB-APEX2 fusion proteins

- Perform proximity labeling with biotin-phenol and H₂O₂ stimulation

- Harvest cells and streptavidin-based enrichment of biotinylated proteins

- Digest enriched proteins with trypsin

- Immunoaffinity enrichment of K-ε-GG-containing peptides

- Analyze by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Validate candidate substrates through orthogonal approaches

Reconstituted HUWE1 Ubiquitination Assay [14]:

- Purify E1 (UBA1), E2 (UBE2L3 or UBE2D3), and HUWE1HECT or full-length HUWE1

- Set up reaction buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM ATP

- Combine enzymes with ubiquitin and potential substrates/inhibitors

- Incubate at 30°C for desired time points

- Stop reaction with SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing DTT

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE and western blotting with ubiquitin-specific antibodies

- For inhibitor studies, monitor dose-dependent effects on auto-ubiquitination

BioPROTAC Degradation Kinetic Measurements [8]:

- Purify target protein (e.g., GS-eGFP) and bioPROTAC (e.g., DARPin-CHIPΔTPR fusion)

- Label bioPROTAC with fluorescent dye (TMR5-maleimide)

- Form 1:1 complexes between target and bioPROTAC in vitro

- Microinject pre-formed complexes into HEK293 cell cytosol

- Perform time-lapse fluorescence microscopy to monitor protein levels

- Quantify fluorescence decay in individual cells over time

- Calculate degradation rate constants from single-cell trajectories

Technical Challenges and Methodological Considerations

Key Challenges in Ubiquitination Research

Ubiquitination research faces several technical challenges that complicate data interpretation. The low stoichiometry of ubiquitination under physiological conditions makes detection difficult without enrichment strategies [6]. The transient nature of ubiquitination due to active deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) requires use of proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) or DUB inhibitors to preserve signals [11]. Linkage complexity presents analytical challenges, as polyubiquitin chains can be homotypic, mixed, or branched with different functional consequences [12].

Method-specific limitations include artifacts from tagged ubiquitin expression that may not fully replicate endogenous ubiquitin dynamics [6]. Antibody specificity issues plague the field, with many commercial ubiquitin antibodies showing cross-reactivity or poor linkage specificity [11]. Cellular context loss in in vitro systems may fail to recapitulate physiological regulation, while complexity of intracellular environments in in vivo systems can obscure specific mechanisms [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Expression Constructs | His-Ub, HA-Ub, Strep-Ub, GFP-Ub | Affinity purification, microscopy, ubiquitinome profiling [6] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-specific, K63-specific, M1-specific antibodies | Detection of specific chain types, immunohistochemistry [6] |

| Pan-Ubiquitin Antibodies | P4D1, FK1, FK2 | General ubiquitination detection, western blotting [6] |

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Tools | Ubiquitin-Trap (nanobody-based), TUBEs | Pull-down of ubiquitinated proteins, stabilization against DUBs [11] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | MG-132 (proteasome inhibitor), TAK243 (E1 inhibitor) | Pathway inhibition, stabilization of ubiquitinated species [9] [11] |

| Recombinant Enzymes | E1 (UBA1), E2s (UBE2L3, UBE2D3), E3s (HUWE1, Parkin) | In vitro ubiquitination assays, mechanism studies [14] |

| Activity Probes | Ubiquitin vinyl sulfone, HA-Ub-VS | DUB activity profiling, enzyme characterization |

| Mass Spec Standards | DiGly remnant peptides, SILAC-labeled ubiquitin | Quantitative proteomics, site identification [13] |

Research Applications and Future Directions

Applications in Drug Discovery and Disease Research

Ubiquitination detection methodologies have enabled significant advances in understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies. In cancer research, detection of aberrant ubiquitination has revealed dysregulated pathways in cell cycle control and DNA damage response [4]. Small molecule inhibitors targeting specific E3 ligases, such as Nutlin against MDM2, have shown promise in clinical trials for treating cancers like multiple myeloma [4]. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib has become an established treatment for multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma [4].

In neurodegenerative disease research, characterization of ubiquitin chains in pathological protein aggregates has provided insights into disease mechanisms. For example, K48-linked polyubiquitination of tau protein was found to be abnormally accumulated in Alzheimer's disease [6]. Understanding these patterns may lead to novel therapeutic strategies targeting the ubiquitin system.

The emerging field of targeted protein degradation has leveraged insights from ubiquitination mechanisms to develop novel therapeutic modalities. PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) and bioPROTACs use the ubiquitin system to selectively degrade disease-causing proteins, with applications in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and genetic disorders [8]. These approaches demonstrate how fundamental research on ubiquitination mechanisms can translate into innovative therapeutic strategies.

Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

Future developments in ubiquitination research will likely focus on single-cell ubiquitinomics to capture cell-to-cell heterogeneity, spatiotemporally resolved detection to monitor ubiquitination dynamics in real-time, and improved linkage-specific reagents to better discriminate between ubiquitin chain architectures [13] [8].

The integration of chemical biology tools with genetic approaches will enable more precise manipulation and monitoring of ubiquitination events. For example, the development of photo-crosslinkable ubiquitin variants could help capture transient ubiquitination events, while improved mass spectrometry methods may enable comprehensive analysis of branched chain architectures [12].

As our understanding of the complexity of ubiquitin signals grows, so does the appreciation for its role in integrating cellular information. The continued development of sophisticated detection methodologies will be essential for deciphering this complex regulatory code and harnessing its potential for therapeutic intervention.

Visualizing Ubiquitination Pathways and Detection Methods

Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade and Signaling Outcomes

Proximal-Ubiquitinome Profiling Workflow

Ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins, is a fundamental post-translational modification regulating diverse cellular processes including protein degradation, DNA repair, and cell signaling [4]. The detection and accurate quantification of ubiquitination events are therefore critical for understanding cellular homeostasis and developing therapies for diseases such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [4] [15]. However, researchers face significant technical challenges in ubiquitination studies, primarily stemming from the low stoichiometry of modification, transient nature of ubiquitin signaling, and constant interference from deubiquitinases (DUBs) that rapidly reverse these modifications [16] [15]. This guide compares the performance of contemporary methodologies addressing these hurdles, providing experimental data and protocols to inform research design.

The Core Technical Hurdles in Ubiquitin Research

Low Stoichiometry of Modification

Ubiquitination typically occurs at low levels, with only a small fraction of any target protein being modified at a given time [17]. This low stoichiometry presents substantial detection challenges, as the signal from modified species is often obscured by abundant unmodified proteins. Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics reveals that most ubiquitination sites exhibit low occupancy, acting as subtle modulators rather than binary switches [17]. This necessitates highly sensitive enrichment and detection methods to capture meaningful biological signals.

Transient Nature of Ubiquitination

The dynamic balance between ubiquitination by E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascades and deubiquitination by DUBs creates transient ubiquitination states [4] [15]. This transient nature means ubiquitination events can be brief, making them difficult to capture without methodological interventions. The half-life of ubiquitin-protein conjugates is often short, particularly for substrates targeted to the proteasome, requiring precise temporal control in experimental setups.

Deubiquitinase Interference

Approximately 100 human DUBs constantly oppose ubiquitination by cleaving ubiquitin from modified substrates [15] [18]. This DUB activity presents a major interference factor in ubiquitination studies, as it can rapidly remove ubiquitin signals during cell lysis and sample processing. Different DUB families (USP, UCH, OTU, MJD, MINDY, ZUFSP, and JAMM) exhibit varying linkage specificities and cellular functions, adding complexity to this interference [19] [18]. Bacterial pathogens have even evolved DUB effectors that interfere with host ubiquitination, highlighting the ubiquity of this challenge [20].

Table 1: Major Deubiquitinase Families and Their Characteristics

| DUB Family | Catalytic Mechanism | Representative Members | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP (Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases) | Cysteine protease | USP7, USP9X | Largest family (58 members), generally linkage-promiscuous |

| UCH (Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolases) | Cysteine protease | UCH-L1, UCH-L3 | Prefer small adducts or unstructured C-termini |

| OTU (Ovarian Tumor Proteases) | Cysteine protease | OTUD1, A20 | Often linkage-specific (e.g., K63-specific OTUD1) |

| MJD (Machado-Josephin Domain Proteases) | Cysteine protease | Ataxin-3, JosD1 | Josephin domain-containing, involved in neurodegeneration |

| MINDY | Cysteine protease | MINDY-1, MINDY-2 | K48-linkage specific, senses chain length |

| ZUFSP | Cysteine protease | ZUP1 | K63-specific, associated with genome integrity |

| JAMM | Zinc metalloprotease | PSMD14, AMSH | Requires zinc ions, only metalloprotease DUB family |

Methodological Comparisons: Addressing the Key Hurdles

Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches

Modern mass spectrometry techniques, particularly Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA-MS), have revolutionized ubiquitinome profiling by simultaneously addressing multiple technical challenges.

Performance Comparison: DIA-MS significantly outperforms traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) methods, quantifying over 68,000 ubiquitinated peptides in single runs compared to approximately 21,400 with DDA [16]. This enhanced coverage is crucial for detecting low-stoichiometry modifications. DIA-MS also demonstrates superior quantitative precision, with median coefficients of variation (CV) of approximately 10% across replicates, enabling reliable detection of transient dynamics [16].

Experimental Protocol (DIA-MS Ubiquitinomics):

- Cell Lysis: Use sodium deoxycholate (SDC) buffer supplemented with 40mM chloroacetamide (CAA) for immediate cysteine protease inhibition [16].

- Protein Digestion: Perform tryptic digestion to generate ubiquitin remnant peptides containing diglycine (K-ε-GG) signatures.

- Peptide Enrichment: Use immunoaffinity purification with anti-K-ε-GG antibodies to isolate ubiquitinated peptides.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze using DIA-MS with 75-minute nanoLC gradients and optimized MS methods.

- Data Processing: Utilize DIA-NN software in "library-free" mode for identification and quantification [16].

Table 2: Comparison of Ubiquitinomics Method Performance

| Method | Sensitivity (Peptides Identified) | Quantitative Precision (Median CV) | Sample Input | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDA-MS with Urea Lysis | ~19,400 peptides | >20% | 2mg protein | Low (50% missing values in replicates) |

| DDA-MS with SDC Lysis | ~26,750 peptides | 15-20% | 2mg protein | Moderate |

| DIA-MS with SDC Lysis | ~68,400 peptides | ~10% | 2mg protein | High (88% overlap between replicates) |

| UbiSite Method | ~30,000 peptides | Not specified | 40mg protein | Very Low (requires fractionation) |

Biochemical and Cellular Assays

For functional validation of specific ubiquitination events, biochemical approaches provide complementary information to proteomic methods.

DUB Inhibition Studies: Targeted inhibition of specific DUBs combined with ubiquitinomics enables mapping of DUB substrates and distinction between degradative and non-degradative ubiquitination. Upon USP7 inhibition, hundreds of proteins show increased ubiquitination within minutes, but only a small fraction undergo degradation, revealing the complex regulatory landscape [16].

Experimental Protocol (In Vitro Deubiquitination Assay):

- Substrate Preparation: Generate ubiquitinated substrates using recombinant E1, E2, and E3 enzymes or by immunopurification from cells treated with proteasome inhibitors.

- DUB Incubation: Incubate ubiquitinated substrates with purified DUBs or cell lysates expressing DUBs.

- Reaction Conditions: Use appropriate buffers (typically Tris or HEPES, pH 7.5-8.0, with DTT for cysteine DUBs).

- Detection: Monitor deubiquitination by immunoblotting with ubiquitin-specific antibodies or by changes in substrate molecular weight [15] [18].

Advanced Methodologies for Specific Challenges

Addressing Stoichiometry: Site-specific ubiquitination stoichiometry can be quantified using chemical labeling, isotopic tagging, and targeted proteomic approaches [17]. These methods reveal functional thresholds where ubiquitination transitions from subtle modulation to decisive regulatory switch.

Capturing Transient Events: Rapid inhibition techniques using specific DUB inhibitors or crosslinking strategies help preserve transient ubiquitination states. Time-resolved analyses with high temporal resolution enable tracking of ubiquitination dynamics [16].

Countering DUB Interference: Immediate protease inhibition during cell lysis is critical. SDC lysis with CAA alkylation rapidly inactivates DUBs, resulting in 38% more ubiquitinated peptide identifications compared to urea-based methods [16]. Additionally, specific DUB inhibitors and ubiquitin variants (UbVs) can target particular DUB families [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitors | Chloroacetamide (CAA), N-ethylmaleimide | Rapid cysteine protease/DUB inhibition during lysis |

| Lysis Buffers | SDC (Sodium Deoxycholate) buffer | Efficient extraction with concurrent DUB inhibition |

| DUB Inhibitors | MLN4924 (NAE1 inhibitor), P5091 (USP7 inhibitor) | Specific pathway inhibition to study ubiquitination dynamics |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG-132, Bortezomib | Prevent degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, enhancing detection |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-based ABPs with warhead groups | Profiling DUB activity and specificity in complex mixtures |

| Ubiquitin Variants | Linkage-specific UbVs (e.g., K48-, K63-specific) | Inhibiting specific DUBs or recognizing particular chain types |

| Enrichment Reagents | Anti-K-ε-GG antibodies, TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins/peptides |

| Mass Spec Standards | Heavy-labeled ubiquitin remnant peptides | Quantitative precision and normalization in proteomics |

Visualization of Key Concepts

Ubiquitination-DUB Balance and Methodological Interventions

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Ubiquitinomics

The methodological landscape for studying ubiquitination has evolved significantly to address the core challenges of low stoichiometry, transient dynamics, and DUB interference. Integrated approaches combining optimized sample preparation (SDC/CAA lysis), advanced mass spectrometry (DIA-MS), and specific pharmacological tools (DUB inhibitors) now enable comprehensive analysis of ubiquitination events that were previously undetectable. As these technologies continue to advance, particularly through improved quantitative accuracy and temporal resolution, researchers will gain unprecedented insights into the complex regulatory networks governed by ubiquitin signaling, accelerating both basic biological discovery and therapeutic development.

Ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of a small regulatory protein called ubiquitin to target substrates, represents one of the most versatile post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells. This highly conserved process regulates virtually every cellular pathway, with particular significance for maintaining protein homeostasis through directed proteasomal degradation. The ubiquitination machinery consists of a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases, with counterbalancing activity provided by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin modifications [21] [22]. The system's importance in human disease stems from its regulatory control over fundamental cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, signal transduction, and immune responses [22].

Dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways manifests differently across disease states. In cancer, mutations in ubiquitin system components often drive uncontrolled proliferation and evasion of cell death, while in neurodegenerative disorders, impaired ubiquitin-mediated clearance of toxic protein aggregates leads to neuronal dysfunction and death [21] [23]. This review examines the distinct and overlapping roles of ubiquitination in these disease contexts, with particular emphasis on comparing methodologies for detecting ubiquitination events in experimental models—a critical consideration for both basic research and drug development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Ubiquitination in Cancer

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) contributes to multiple hallmarks of cancer, influencing cellular survival, proliferation, and metabolic reprogramming. Cancer-associated dysregulation occurs through mutations in ubiquitin pathway enzymes or through the hijacking of normal ubiquitination mechanisms to destabilize tumor suppressor proteins [21] [22].

E3 Ligases and DUBs as Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressors

E3 ubiquitin ligases demonstrate remarkable substrate specificity, with many functioning as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on their target proteins. For instance, the E3 ligase MDM2 acts as an oncogene by targeting tumor suppressor p53 for degradation, while BRCA1 functions as a tumor suppressor through its role in DNA damage repair [22]. The following table summarizes key E3 ligases and their roles in cancer:

Table 1: Key E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in Cancer Pathogenesis

| E3 Ligase | Category | Key Substrate(s) | Associated Cancers | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDM2 | Oncogene | p53 | Sarcomas, breast, lung | Proteasomal degradation of tumor suppressor |

| E6AP | Oncogene | p53 | HPV-associated cancers | Viral hijacking leads to p53 degradation |

| SCFSkp2 | Oncogene | p27 | Lung, glioma, gastric, prostate | Cell cycle progression |

| VHL | Tumor Suppressor | HIF-1α | Renal cell carcinoma | Regulates tumor vascularization |

| BRCA1 | Tumor Suppressor | Multiple DNA repair proteins | Breast, ovarian | DNA damage response |

Similarly, deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) counterbalance E3 ligase activity, with several functioning as oncoproteins. For example, ubiquitin-specific protease 2 (USP2) stabilizes the immune checkpoint protein PD-1, thereby promoting tumor immune escape through deubiquitination [21]. The DUB OTUB2 enhances glycolysis and accelerates colorectal cancer progression by inhibiting Parkin-mediated ubiquitination of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) [21].

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Ubiquitination

Novel anticancer strategies increasingly leverage the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) represent a groundbreaking approach that redirects E3 ligase activity to specifically degrade disease-causing proteins. ARV-110 and ARV-471 exemplify this technology, having progressed to phase II clinical trials for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and breast cancer, respectively [21]. Molecular glues offer an alternative degradation strategy with smaller molecular dimensions, simplifying optimization of pharmaceutical properties. CC-90009, which promotes degradation of GSPT1, is currently in phase II trials for leukemia therapy [21].

Ubiquitination Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Disorders

In contrast to cancer, neurodegenerative diseases typically involve failures in ubiquitin-dependent protein quality control mechanisms. The post-mitotic nature of neurons makes them particularly vulnerable to accumulated protein damage, as they cannot dilute toxic aggregates through cell division [23].

Protein Aggregation and Impaired Clearance Mechanisms

A hallmark of most neurodegenerative disorders is the accumulation of ubiquitin-positive protein aggregates, indicating a failure of normal degradation pathways. Key aggregated proteins include β-amyloid and tau in Alzheimer's disease, α-synuclein in Parkinson's disease, huntingtin in Huntington's disease, and TDP-43 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [23] [24]. These aggregates often contain ubiquitin and components of the ubiquitination machinery, suggesting attempted clearance by proteasomal and autophagic pathways.

The two main degradation pathways—the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy-lysosomal pathway (ALP)—both depend on ubiquitin signaling. The UPS primarily degrades soluble, misfolded proteins modified with K48-linked ubiquitin chains, while autophagy (particularly aggrephagy) clears larger protein aggregates tagged with K63-linked chains via receptors like p62/SQSTM1 [23] [24]. Aging-associated decline in both pathways contributes to the late onset of most neurodegenerative conditions.

Disease-Linked Mutations in Ubiquitin System Components

Several familial forms of neurodegeneration result from mutations in genes encoding ubiquitin pathway components. Parkinson's disease provides compelling examples, with loss-of-function mutations in the E3 ligase Parkin (PRKN) and its upstream kinase PINK1 causing autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism [23]. These proteins coordinate a quality control pathway for damaged mitochondria (mitophagy), with PINK1 accumulating on dysfunctional mitochondria to recruit and activate Parkin, which ubiquitinates mitochondrial outer membrane proteins to trigger autophagic clearance [23].

Table 2: Ubiquitin Pathway Components in Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Key Aggregated Protein | Relevant Ubiquitin System Component | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | β-amyloid, tau | UCHL1, USP14 | Proteasomal impairment |

| Parkinson's Disease | α-synuclein | Parkin (E3), PINK1 | Impaired mitophagy |

| Huntington's Disease | Huntingtin | E3 ligases (CHIP) | Aggregate clearance failure |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | TDP-43, SOD1 | UBQLN2, OPTN | Defective autophagy |

| Angelman Syndrome | - | UBE3A/E6AP (E3) | Neurodevelopmental defects |

Frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have been linked to mutations in UBQLN2, which encodes a proteasome shuttle factor, and OPTN, which encodes an autophagy receptor [23]. These genetic connections underscore the critical importance of efficient ubiquitin-mediated degradation for neuronal survival.

Comparative Analysis: Detection Methods for Ubiquitination

Understanding ubiquitination in disease contexts relies on robust detection methodologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The choice between in vivo and in vitro approaches depends on the research question, with considerations for biological relevance versus experimental control.

In Vivo Ubiquitination Detection

The most common method for detecting protein ubiquitination in living cells involves immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting under stringent conditions to eliminate non-covalent interactions [25].

Protocol: In Vivo Ubiquitination Assay in Cultured Cells

- Transfection: Introduce plasmids expressing the protein of interest and epitope-tagged ubiquitin into cultured cells.

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells using complete lysis buffer (2% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) containing protease inhibitors and deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors (N-ethylmaleimide or ubiquitin aldehyde).

- Denaturation: Immediately boil samples for 10 minutes to denature proteins and inactivate DUBs.

- Shearing: Sonicate lysates to shear DNA and reduce viscosity.

- Dilution: Add dilution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton) and incubate at 4°C for 30-60 minutes with rotation.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate pre-cleared lysates with antibody-conjugated Protein A/G beads targeting the protein of interest overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash beads extensively with high-stringency buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40).

- Analysis: Elute proteins by boiling in SDS sample buffer, then perform immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin and target protein antibodies [25].

This approach preserves physiological enzyme-substrate relationships and regulatory mechanisms but may be complicated by endogenous ubiquitin and low abundance of modified species.

In Vitro Ubiquitination Detection

Reconstituted ubiquitination assays using purified components offer precise control over reaction conditions and enzyme composition.

Protocol: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

- Reaction Setup: For each 40μL reaction, combine:

- 8μL 5X ubiquitination buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl₂, 2.5 mM DTT, 10 mM ATP)

- 250 ng E1 activating enzyme

- 500 ng E2 conjugating enzyme

- 0.5-1 μg E3 ligase (if testing E3-dependent ubiquitination)

- 0.5 μg ubiquitin

- 0.5 μg substrate protein

- Water to 40μL total volume

- Control Reactions: Prepare parallel reactions omitting E1, E2, E3, or ubiquitin to confirm specificity.

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C for 1-2 hours.

- Termination: Stop reactions by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling for 10 minutes.

- Analysis: Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE and detect ubiquitination by immunoblotting [25].

This method allows direct assessment of specific enzyme requirements and kinetic parameters but lacks cellular context and regulatory complexity.

Table 3: Comparison of Ubiquitination Detection Methods

| Parameter | In Vivo Detection | In Vitro Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Biological relevance | High, maintains cellular context | Limited, reduced complexity |

| Experimental control | Lower, multiple variables | High, defined components |

| Detection sensitivity | May require overexpression | Direct visualization possible |

| Equipment requirements | Standard cell culture and molecular biology | Protein purification capabilities |

| Technical challenges | Non-specific interactions, DUB activity | Enzyme stability, reconstitution efficiency |

| Applications | Disease mechanisms, drug screening | Enzyme mechanics, biochemical characterization |

Experimental Visualization and Research Tools

Key Signaling Pathways in Ubiquitination-Related Diseases

The following diagrams illustrate critical ubiquitin-dependent pathways in cancer and neurodegeneration, created using DOT language with specified color palette:

Diagram 1: PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy pathway relevant to Parkinson's disease.

Diagram 2: HPV E6/E6AP-mediated p53 degradation pathway in cervical cancer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzymes | UBA1, UBA6 | Initiates ubiquitin activation | Essential for all in vitro assays |

| E2 Conjugating Enzymes | UBE2D, UBE2R, UBE2N/UEV1 | Ubiquitin chain formation | Determine linkage specificity |

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligases | Parkin, MDM2, BRCA1, E6AP | Substrate recognition | High specificity; often mutated in disease |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | USP14, UCHL1, OTUB1, CYLD | Reverse ubiquitination | Use inhibitors in detection assays |

| Ubiquitin Variants | Wild-type, K48-only, K63-only, HA-tagged, FLAG-tagged | Chain linkage studies | Tags enable detection in assays |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132 | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins | Can induce stress responses |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619, N-ethylmaleimide | Prevent deubiquitination | Improve detection sensitivity |

| Antibodies | Anti-ubiquitin, anti-K48, anti-K63 linkage-specific | Detection and quantification | Variable specificity between lots |

The investigation of ubiquitination in human disease reveals both shared mechanisms and pathological specializations between cancer and neurodegeneration. In cancer, ubiquitination pathways are typically hyperactive or hijacked to promote growth and survival, while in neurodegenerative conditions, impaired ubiquitin-mediated degradation enables toxic accumulation of misfolded proteins. These distinctions have profound implications for therapeutic development, with cancer strategies often aiming to inhibit specific E3 ligases or proteasomal activity, while neurodegenerative approaches seek to enhance ubiquitin-mediated clearance.

Methodologically, the complementary use of in vivo and in vitro detection techniques provides the most comprehensive understanding of ubiquitination events. In vivo approaches maintain physiological context essential for disease modeling, while in vitro methods offer mechanistic precision for dissecting molecular interactions. The continuing development of targeted protein degradation technologies like PROTACs underscores the therapeutic potential of manipulating ubiquitination pathways, offering promising avenues for addressing previously "undruggable" targets in both cancer and neurodegeneration.

A Practical Guide to Established and Next-Generation Detection Techniques

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting in Cultured Cells

Protein ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular functions, including proteasomal degradation, signal transduction, and immune responses [26] [6]. The detection of ubiquitination in cultured cells provides critical insights into protein regulation under physiological conditions, enabling researchers to study this dynamic process within its native cellular context. Unlike in vitro approaches, in vivo detection preserves the complex regulatory environment of the cell, including the full complement of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes, deubiquitinases (DUBs), and competing post-translational modifications [27] [6]. This guide objectively compares immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting methodologies for detecting ubiquitination in cultured cells, evaluating their performance against alternative techniques while providing detailed experimental protocols and data for researcher implementation.

Core Methodology: Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting Workflow

The standard protocol for detecting protein ubiquitination in cultured cells involves immunoprecipitation of the target protein under denaturing conditions, followed by immunoblotting with ubiquitin-specific antibodies [25]. This approach enables researchers to confirm whether a specific protein is ubiquitinated and to compare ubiquitination levels under different experimental conditions.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Cell Lysis under Denaturing Conditions:

- Aspirate culture medium and lyse cells directly in 100-200μl of hot SDS-containing lysis buffer (2% SDS, 150mM NaCl, 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) supplemented with protease inhibitors (e.g., 2mM sodium orthovanadate, 50mM sodium fluoride) and DUB inhibitors (N-ethylmaleimide or ubiquitin aldehyde) to prevent deubiquitination during processing [25] [6].

- Immediately boil cell lysates for 10 minutes to denature proteins and inactivate DUBs [25].

- Sonicate samples to shear genomic DNA and reduce sample viscosity.

Immunoprecipitation:

- Dilute the denatured lysates 10-fold with dilution buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) to reduce SDS concentration below its critical micelle concentration (0.1-0.2%) [25].

- Incubate diluted lysates with target protein-specific antibody conjugated to Protein A/G agarose beads (14-20μl of 50% slurry per 500-1500μg total protein) at 4°C overnight with rotation [25].

- Pellet beads by centrifugation at 5,000×g for 5 minutes and wash twice with high-stringency buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1M NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% NP-40) to remove non-specifically bound proteins [25].

- After final wash, completely remove residual buffer and elute immunoprecipitated proteins by boiling beads in 2X SDS-PAGE loading buffer for 10 minutes [25].

Immunoblotting:

- Separate immunoprecipitated proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF or nitrocellulose membranes.

- Probe membranes with ubiquitin-specific antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1, FK2) to detect ubiquitinated target protein [6].

- Stripping and re-probing membranes with antibody against the target protein confirms equal precipitation across samples [25].

The following diagram illustrates this core experimental workflow:

Performance Comparison with Alternative Methods

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting offer distinct advantages and limitations compared to other ubiquitination detection methods. The table below provides a systematic comparison of key performance characteristics:

| Method | Throughput | Sensitivity | Linkage Specificity | Required Resources | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP + Immunoblotting | Low to moderate | High (detects endogenous proteins) | No (unless linkage-specific antibodies) | Standard molecular biology equipment | Target protein validation, time-course studies [26] [25] |

| TUBE-Based Assays | High (96/384-well format) | Very high (nanomolar affinity) | Yes (chain-specific TUBEs) | Specialized TUBE reagents | High-throughput screening, linkage-specific analysis [26] |

| Ubiquitin Tagging (StUbEx) | Moderate | Moderate | No | Cell lines expressing tagged ubiquitin | Proteomic screening of ubiquitinated proteins [6] |

| Mass Spectrometry | High for discovery | Lower for site mapping | Yes with advanced methods | Specialized instrumentation | Global ubiquitinome profiling, site identification [28] [6] |

| In Vitro Reconstitution | Moderate | High for direct substrates | Controllable | Purified enzyme components | Mechanism dissection, direct substrate validation [27] |

Quantitative Performance Data

Recent studies provide direct comparisons of methodological performance:

Signal Detection Sensitivity: TUBE-based assays demonstrate nanomolar affinities for polyubiquitin chains, significantly enhancing detection sensitivity compared to standard immunoblotting [26]. In studies of RIPK2 ubiquitination, TUBE-based approaches enabled clear differentiation between K48- and K63-linked ubiquitination in response to different stimuli (L18-MDP vs. RIPK2 PROTAC), while standard IP/immunoblotting showed limited linkage discrimination [26].

Throughput Capacity: Traditional IP/immunoblotting is considered low-throughput, requiring 1-2 days for processing limited sample numbers. In contrast, TUBE-based HTS assays have been successfully implemented in 96-well plate formats, enabling rapid quantification of endogenous protein ubiquitination dynamics [26].

Target Specificity: IP/immunoblotting provides high target specificity when quality antibodies are available. However, a comparative study of E3 ligases found that some targets initially identified in cellular studies could not be validated in direct in vitro assays (e.g., CRL3SPOP with PD-L1), highlighting potential false positives in complex cellular environments [27].

Advanced Applications and Modifications

Linkage-Specific Detection

While standard IP/immunoblotting does not inherently distinguish ubiquitin linkage types, researchers can incorporate linkage-specific reagents to gain this information:

Linkage-Specific Antibodies: Antibodies specifically recognizing K48, K63, M1, or other linkage types can be used in immunoblotting steps [6]. For example, K48-linkage specific antibodies have been used to demonstrate abnormal tau ubiquitination in Alzheimer's disease [6].

Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs): TUBEs with specificity for particular chain types can be incorporated into the IP step. In a recent study, K63-TUBEs successfully captured L18-MDP-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination, while K48-TUBEs captured PROTAC-induced ubiquitination [26].

The following diagram illustrates how these advanced reagents enable linkage-specific detection:

Quantitative Dynamic Analysis

IP and immunoblotting can be adapted to monitor ubiquitination dynamics:

Time-Course Studies: Monitoring RIPK2 ubiquitination at 30 and 60 minutes after L18-MDP stimulation revealed higher ubiquitination at the earlier time point, demonstrating the method's applicability for kinetic studies [26].

Inhibitor Characterization: Pre-treatment with Ponatinib (100 nM) completely abrogated L18-MDP-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination, demonstrating how this approach can characterize ubiquitination pathway inhibitors [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful detection of ubiquitination in cultured cells requires specific reagents to preserve and detect this labile modification:

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | N-ethylmaleimide, Ubiquitin aldehyde | Prevent deubiquitination during cell lysis and processing [25] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevent protein degradation during sample preparation [25] |

| Denaturing Lysis Buffer | 2% SDS, 150mM NaCl, 10mM Tris-HCl | Denatures proteins and disrupts non-covalent interactions [25] |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | P4D1, FK1, FK2 | Detect ubiquitinated proteins in immunoblotting [6] |

| Linkage-Specific Reagents | K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs, linkage-specific antibodies | Enable discrimination of ubiquitin chain types [26] [6] |

| Positive Control Compounds | L18-MDP, PROTACs, MG-132 (proteasome inhibitor) | Induce ubiquitination for protocol validation [26] [28] |

Methodological Limitations and Considerations

Despite its widespread use, researchers must recognize several important limitations of the IP/immunoblotting approach:

Stoichiometry Challenges: Ubiquitination is typically a low-stoichiometry modification, with the majority of ubiquitination sites identified in proteomic studies showing low modification rates [28]. This can make detection challenging without enrichment or signal amplification.

Antibody Specificity Issues: Commercial ubiquitin antibodies vary considerably in their specificity and ability to recognize different ubiquitin chain types. Validation with appropriate controls is essential [6].

Linkage Discrimination Limitations: Standard IP/immunoblotting does not inherently distinguish between ubiquitin linkage types without specialized reagents [26] [6].

Throughput Constraints: The multi-step nature of IP and immunoblotting limits its throughput compared to plate-based or proteomic approaches [26].

Immunoprecipitation combined with immunoblotting remains a foundational methodology for detecting protein ubiquitination in cultured cells, offering robust target-specific detection with accessible laboratory equipment. While newer approaches like TUBE-based assays provide enhanced sensitivity and linkage specificity, and mass spectrometry enables global ubiquitinome profiling, the direct visual confirmation provided by immunoblotting continues to make it a verification standard in the field. By incorporating appropriate controls, DUB inhibitors, and potentially linkage-specific reagents, researchers can reliably employ this technique to investigate ubiquitination dynamics in physiological and pathological contexts.

In vitro reconstitution represents a foundational methodology in the study of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, enabling researchers to deconstruct complex cellular signaling into defined biochemical steps. This approach involves assaying ubiquitination using a complete set of purified components—E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, E3 ligases, ubiquitin, and a substrate—in a controlled test tube environment [29]. By isolating the enzymatic cascade from the intricate cellular milieu, scientists can dissect precise molecular mechanisms, define minimal requirements for activity, and characterize the specificity of E3 ligases and their downstream effects [30] [27]. As research increasingly highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting ubiquitination pathways, from PROTACs to molecular glues [26], the role of in vitro reconstitution in validating and characterizing these mechanisms has never been more critical. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of in vitro reconstitution methodologies, detailing experimental protocols, key findings, and strategic applications to empower researchers in selecting the optimal approach for their ubiquitination studies.

Core Principles and Methodologies of In Vitro Reconstitution

The Biochemical Foundation of the Ubiquitination Cascade

The ubiquitination cascade is a sequential process catalyzed by three enzyme families. The E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme initiates the cycle in an ATP-dependent manner, forming a high-energy thioester bond with ubiquitin. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the catalytic cysteine of an E2 conjugating enzyme. Finally, an E3 ubiquitin ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine ε-amino group on the target protein substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [4] [29]. HECT-type and RBR-type E3 ligases employ a unique catalytic mechanism, forming a transient thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate, whereas RING-type E3s facilitate direct transfer from the E2 to the substrate [31] [32].

In vitro reconstitution replicates this cascade using recombinant proteins, allowing researchers to define the exact composition of the reaction mixture. This reductionist approach enables precise control over variables including enzyme concentrations, reaction conditions, and timing—parameters that are often difficult to manipulate in cellular environments [27]. The typical workflow begins with the preparation of recombinant enzymes and substrates, followed by assembly of the reaction mixture with essential co-factors (notably ATP), incubation under controlled conditions, and finally, termination of the reaction and analysis of products, typically via SDS-PAGE and Western blotting [33] [29].

Standardized Experimental Protocol for In Vitro Ubiquitination

The following protocol outlines the core steps for conducting an in vitro ubiquitination assay, synthesizing methodologies from multiple recent studies [27] [29]:

- Recombinant Protein Preparation: Express and purify the E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme, E3 ligase, and substrate protein. For transmembrane proteins like PD-L1, a recombinant cytoplasmic domain (e.g., amino acids 260-290) is often sufficient and simplifies purification [27].

- Reaction Mixture Assembly: Combine the following components in a reaction buffer:

- ATP-regenerating system (ATP, Mg²⁺)

- Recombinant ubiquitin (wild-type or mutant)

- E1 activating enzyme (e.g., Uba1)

- E2 conjugating enzyme (e.g., Ubc4, UbcH5c, or UBE2L3)

- E3 ubiquitin ligase

- Target substrate protein

- Incubation and Reaction Termination: Incubate the reaction mixture at 30°C for 30-90 minutes. Terminate the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer and boiling for 5-10 minutes.

- Product Analysis: Resolve the reaction products by SDS-PAGE. Analyze ubiquitination using Western blotting with antibodies specific for ubiquitin (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) or an epitope tag on the substrate (e.g., anti-HA, anti-biotin) [30] [27].

Table 1: Essential Components for a Standard In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

| Component | Function | Example Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner | Uba1 |

| E2 Enzyme | Carries activated ubiquitin | Ubc4, UbcH5c, CDC34B |

| E3 Ligase | Recognizes substrate and catalyzes ubiquitin transfer | Ufd4, TRIP12, ARIH1, NEDD4, HOIL-1 |

| Ubiquitin | The modifying protein | Wild-type Ub, Ub mutants (K29R, K48R, etc.) |

| Substrate | The target protein for modification | PD-L1 cytoplasmic domain, K48-linked diUb |

| Cofactors | Provides energy for the enzymatic reaction | ATP, Mg²⁺ |

Diagram 1: The core ubiquitination enzyme cascade. E1 activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent step, E2 carries the activated ubiquitin, and E3 facilitates final transfer to the substrate.

Comparative Analysis of In Vitro Applications and E3 Ligase Mechanisms

The true power of in vitro reconstitution emerges when comparing activities across different E3 ligase families and substrate types, revealing distinct mechanistic insights that are often obscured in cellular environments.

Recent structural and biochemical studies have meticulously delineated how different E3 ligases dictate ubiquitin chain topology. A prime example is the HECT-type E3 ligase Ufd4, which preferentially synthesizes K29-linked ubiquitin chains onto pre-existing K48-linked diubiquitin to form K29/K48-branched ubiquitin chains [31]. Biochemical assays demonstrated that ubiquitination efficiency escalated with increasing length of the K48-linked ubiquitin chain substrate (tri-, tetra-, penta-Ub). Enzyme kinetics further revealed a ~5.2-fold higher catalytic efficiency ((k{cat}/Km)) for the proximal K29 site (0.11 μM⁻¹ min⁻¹) compared to the distal K29 site (0.021 μM⁻¹ min⁻¹) within a K48-linked diUb substrate [31].

In contrast, studies on RBR-family E3 ligases like HOIL-1 reveal a capacity for non-canonical ubiquitination. HOIL-1 efficiently ubiquitinates serine residues and various saccharides in vitro but shows no activity toward lysine residues. This specificity is governed by a critical catalytic histidine residue (His510) in the flexible active site that enables O-linked ubiquitination while prohibiting ubiquitin discharge onto lysine side chains [32].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of E3 Ligase Activities via In Vitro Reconstitution

| E3 Ligase | Ligase Type | Substrate | Key Findings | Linkage Preference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ufd4/TRIP12 | HECT | K48-linked Ub chains | Preferentially extends K48 chains with K29 linkages; 5.2-fold preference for proximal K29 site [31] | K29-branched on K48 |

| ARIH1 | RBR | PD-L1 cytoplasmic domain | Directly ubiquitinates PD-L1; activity requires release from autoinhibition (e.g., S427D mutation) [27] | Not Specified |

| NEDD4 Family | HECT | PD-L1 cytoplasmic domain | Biochemically validated E3 activity toward PD-L1; redundant activities among family members [27] | Not Specified |

| HOIL-1 | RBR | Serine, Saccharides | Ubiquitinates hydroxyl groups of Ser/saccharides; no Lys activity; depends on His510 [32] | O-linked (Ser, sugars) |

| CRL3SPOP | RING | PD-L1 cytoplasmic domain | No direct ubiquitination observed in vitro despite cellular evidence; suggests need for co-factors [27] | Inactive in minimal system |

Elucidating Non-Canonical Mechanisms and Cooperative Catalysis

In vitro reconstitution has been instrumental in uncovering non-canonical ubiquitination mechanisms that diverge from the standard E1-E2-E3 paradigm. For instance, the RBR E3 ligase ARIH1 can function not only as an independent E3 but also as a "substrate receptor" that cooperates with Cullin RING ligases (CRLs) to form a super-assembly complex for ubiquitination [27]. This cooperative mechanism was elucidated through systematic in vitro mixing of purified components, demonstrating that ARIH1's autoinhibition could be released either by complex formation with neddylated CRLs or by phosphorylation at Ser427 [27].

Furthermore, in vitro studies with HOIL-1 have expanded the scope of ubiquitination beyond protein substrates. Using purified components, researchers demonstrated HOIL-1's ability to ubiquitinate diverse non-protein molecules including maltose, glycogen, and other physiologically relevant di- and monosaccharides [32]. This surprising activity, which could be enhanced using an engineered, constitutively active HOIL-1 variant, enables the production of ubiquitinated saccharides as tool compounds for studying this emerging field of non-proteinaceous ubiquitination.

Diagram 2: Comparative E3 ligase mechanisms. HECT and RBR E3s form transient thioester intermediates with ubiquitin, while RING E3s facilitate direct transfer from E2 to substrate. Some RBR E3s like HOIL-1 can ubiquitinate non-protein substrates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Successful in vitro ubiquitination studies require careful selection of reagents and methodologies. The following toolkit summarizes critical components and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for In Vitro Ubiquitination Studies