Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitinomics: Advanced Proteomic Approaches for Biomarker Discovery and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mass spectrometry (MS)-based ubiquitinomics, a specialized field of proteomics dedicated to profiling protein ubiquitination.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitinomics: Advanced Proteomic Approaches for Biomarker Discovery and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mass spectrometry (MS)-based ubiquitinomics, a specialized field of proteomics dedicated to profiling protein ubiquitination. We explore the fundamental role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in cellular regulation and disease, detail cutting-edge methodological workflows from sample preparation to data acquisition, and present practical troubleshooting guidance. A strong emphasis is placed on the application of these approaches in drug discovery, particularly for targeting deubiquitinases (DUBs) and E3 ligases, and on the critical process of biomarker validation. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement robust ubiquitinomics strategies in translational and clinical research.

The Ubiquitin Signaling Landscape: From Fundamental Biology to Disease Pathways

Introduction The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is the primary pathway for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, playing a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis by regulating the stability, activity, and localization of a vast array of proteins [1] [2] [3]. This system governs essential processes, including the cell cycle, apoptosis, DNA repair, and immune response [1] [4]. The UPS operates through a coordinated enzymatic cascade that conjugates the small protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, marking them for specific fates. Central to this process are ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), ubiquitin ligases (E3), and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [1] [3] [4]. The dysregulation of UPS components is implicated in numerous diseases, particularly cancer, making it a focal point for therapeutic development and basic research [1] [3]. Within this context, mass spectrometry (MS)-based ubiquitinomics has emerged as an indispensable proteomics approach for system-wide profiling of ubiquitination events, enabling the discovery of substrates, the characterization of ubiquitin chain linkages, and the evaluation of drug effects on the ubiquitin landscape [5] [6] [7].

1. The Core Enzymatic Machinery of the UPS The process of ubiquitination is a sequential ATP-dependent enzymatic cascade that culminates in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to a substrate protein.

1.1 The Ubiquitination Cascade The pathway is initiated by an E1 activating enzyme, which activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner and forms a high-energy thioester bond with it [1] [4]. The ubiquitin is then transferred to the active-site cysteine of an E2 conjugating enzyme, also via a thioester bond [1] [3]. Finally, an E3 ubiquitin ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to a lysine residue on the substrate protein, forming an isopeptide bond [1] [3]. A critical feature of the UPS is its extensive diversification at the E2 and E3 levels, with approximately 40 E2s and over 600 E3s encoded in the human genome, which allows for exquisite substrate specificity [1] [3]. E3 ligases are primarily classified into three major groups based on their mechanism and structure: RING (Really Interesting New Gene), HECT (Homologous to the E6AP C-Terminus), and RBR (RING-Between-RING) types [1] [3].

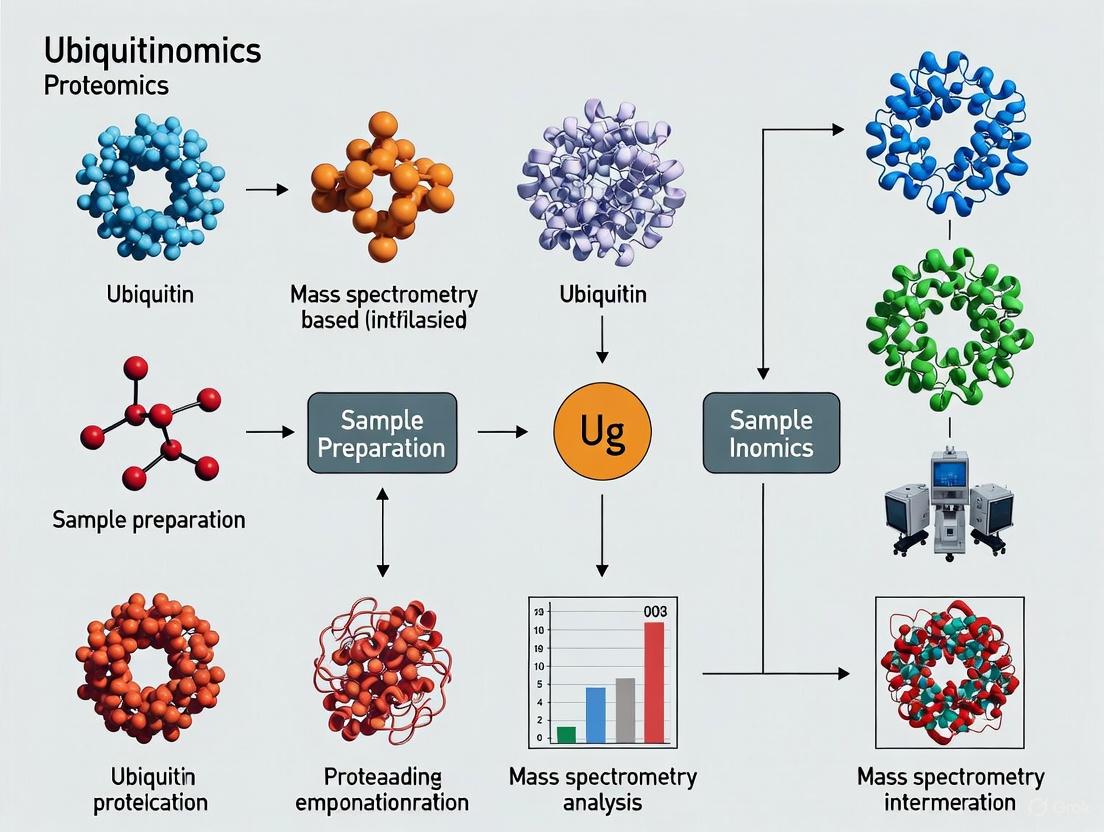

The following diagram illustrates this enzymatic cascade and the key enzymes involved:

1.2 Deubiquitinases (DUBs) and Reversibility Ubiquitination is a dynamic and reversible process. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) are proteases that cleave ubiquitin from substrate proteins, thereby reversing ubiquitin signals [1] [2]. This family of over 90 enzymes in humans is responsible for processing ubiquitin precursors, rescuing substrates from degradation, editing ubiquitin chains, and recycling ubiquitin to maintain a free ubiquitin pool [1] [3] [4]. DUBs are classified into five major families: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USP), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCH), Machado-Joseph domain (MJD), ovarian tumor (OTU) proteases, and JAB1/MPN/MOV34 (JAMM) metalloenzymes [3]. The balance between the activities of E3 ligases and DUBs tightly regulates cellular levels of key proteins like the tumor suppressor p53 [2].

2. Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitinomics: Principles and Workflows MS-based ubiquitinomics enables the global identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites, providing a system-level understanding of ubiquitin signaling [5] [6] [7].

2.1 Fundamental Principles of Ubiquitinomics The core strategy relies on the specific enrichment of peptides derived from ubiquitinated proteins, followed by LC-MS/MS analysis. During tryptic digestion, a ubiquitin-modified lysine residue retains a di-glycine (Gly-Gly, K-ε-GG) remnant with a mass shift of 114.0429 Da, which serves as a mass spectrometry-detectable signature for the ubiquitination site [6] [7] [8]. The primary challenge in ubiquitinomics is the typically low stoichiometry of ubiquitinated species, making affinity enrichment a critical step [7]. Common enrichment methods include:

- Immunoaffinity Purification: Using antibodies specific for the K-ε-GG remnant motif [6] [8].

- DiGly Antibody Enrichment is a cornerstone technique for ubiquitinomics, enabling the specific isolation of tryptic peptides containing the K-ε-GG remnant. This is often performed using commercially available kits like the PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit [8].

- Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs): Utilizing domains that non-covalently bind to ubiquitin or ubiquitin chains [7].

- Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin: Expressing ubiquitin with an N-terminal tag (e.g., His, FLAG, HA, biotin) in cells to allow purification via the tag [5] [7].

2.2 Advanced Ubiquitinomics Workflow (DIA-MS) Recent advances have led to highly robust and deep quantitative ubiquitinomics workflows. The following diagram and protocol detail a state-of-the-art approach using Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry.

- Protocol: Deep Ubiquitinome Profiling Using DIA-MS [6]

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in a lysis buffer containing Sodium Deoxycholate (SDC) supplemented with Chloroacetamide (CAA) for immediate and effective alkylation of cysteine residues. Immediate boiling post-lysis is recommended to rapidly inactivate DUBs and preserve the native ubiquitinome.

- Protein Digestion: Digest proteins using trypsin. The SDC is efficiently removed by acidification after digestion.

- K-ε-GG Peptide Enrichment: Enrich for ubiquitinated peptides using anti-K-ε-GG remnant motif antibody beads. Optimize incubation times and peptide-to-bead ratios for maximum efficiency.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze enriched peptides using liquid chromatography coupled to a mass spectrometer operating in Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) mode. DIA fragments all ions within sequential isolation windows, providing comprehensive and reproducible data.

- Data Analysis: Process the raw DIA data using specialized software like DIA-NN. This deep neural network-based tool can operate in a "library-free" mode, directly querying the data against a protein sequence database, and is optimized for the confident identification and precise quantification of K-ε-GG peptides.

This optimized DIA-MS workflow has been shown to quantify over 70,000 unique ubiquitinated peptides in a single MS run, significantly outperforming traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) methods in coverage, reproducibility, and quantitative precision [6].

3. Quantitative Profiling and Data Interpretation Quantitative proteomic strategies are essential for comparing ubiquitinomes across different biological conditions, such as drug treatments or genetic perturbations.

3.1 Quantitative MS Strategies Two primary methods are widely used:

- Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC): This metabolic labeling method involves culturing cells in "light" (normal) or "heavy" (isotope-labeled) amino acids. Cells from different conditions are combined after culture but before lysis, allowing for accurate relative quantification early in the workflow and minimizing technical variability [7] [8].

- Label-Free Quantification (LFQ): This method quantifies peptides based on their chromatographic peak areas or MS signal intensities across multiple runs without isotopic labeling. It is advantageous for analyzing samples that cannot be metabolically labeled, such as clinical tissues [6].

3.2 Functional Interpretation of Ubiquitinomics Data A key application of quantitative ubiquitinomics is distinguishing between ubiquitination signals that lead to protein degradation and those that mediate non-proteolytic functions. The following table summarizes a computational approach that infers functionality based on changes in ubiquitin occupancy and protein abundance in response to proteasome inhibition [8].

Table 1: Interpreting Ubiquitin Signaling from Proteomic Data Following Proteasome Inhibition

| Observed Change | Proteasome Inhibitor Treatment (e.g., MG-132) | Inferred Function of Ubiquitination | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Occupancy | Protein Abundance | ||

| Increases | No Change or Decreases | Non-Degradative Signaling | Ubiquitination at this site regulates processes like activity, interactions, or trafficking, not proteasomal degradation. |

| Increases | Increases | Degradative Signaling | The substrate is normally targeted by the proteasome; inhibition halts its degradation, causing accumulation of both the protein and its ubiquitinated form. |

| No Change | No Change | Constitutive/Stable Modification | Ubiquitination may have a minor, regulatory, or non-essential role under the conditions studied. |

Application Example: This strategy was successfully applied to profile targets of the deubiquitinase USP7. Upon USP7 inhibition, hundreds of proteins showed increased ubiquitination within minutes. However, by correlating these changes with protein abundance over time, researchers could distinguish the small subset of proteins that were subsequently degraded from the majority that were subject to non-degradative regulatory ubiquitination [6].

4. The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions The following table catalogues essential reagents and tools for conducting MS-based ubiquitinomics research.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Ubiquitinomics Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| K-ε-GG Motif Antibodies | Immunoaffinity purification of ubiquitinated tryptic peptides for MS analysis. | PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit [8]; critical for enriching low-stoichiometry ubiquitinated peptides. |

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin | Enables purification of ubiquitin conjugates under denaturing conditions via the tag. | His-, HA-, FLAG-, or biotin-tagged ubiquitin expressed in cells [5] [7]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Block degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, increasing their abundance for detection. | Bortezomib (FDA-approved), MG-132, Carfilzomib [2] [3] [8]. |

| DUB/USP Inhibitors | Pharmacologically probe DUB function and identify DUB substrates. | Selective USP7 inhibitors (e.g., for mode-of-action studies) [6]. |

| SDC Lysis Buffer | Efficient protein extraction with simultaneous inactivation of DUBs. | Sodium Deoxycholate buffer with Chloroacetamide (CAA); improves ubiquitin site coverage vs. urea [6]. |

| Stable Isotope Labels (SILAC) | For accurate relative quantification of ubiquitinated peptides across conditions. | "Heavy" amino acids (e.g., 13C6-lysine, 13C6-15N4-arginine) [7] [8]. |

| DIA-NN Software | Computational analysis of DIA-MS data for deep, precise ubiquitinome quantification. | Specialized software that boosts identification numbers and quantitative accuracy [6]. |

5. Therapeutic Targeting and Application in Drug Development Components of the UPS are well-validated therapeutic targets in human disease, particularly in oncology [1] [3] [4].

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Bortezomib was the first FDA-approved proteasome inhibitor in 2003 for the treatment of relapsed multiple myeloma. Its success validated the UPS as a target for cancer therapy and spurred drug development efforts focused on other UPS components [1] [2] [4].

- E1 Enzyme Inhibitors: Small-molecule inhibitors of the NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE) have been developed. NEDDylation is crucial for the activity of Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), a major class of E3s, making NAE inhibition a strategy to indirectly dampen the activity of multiple E3s [4].

- E3 Ligase Modulators: E3 ligases are attractive targets due to their substrate specificity. Thalidomide and its analogs (IMiDs) are a prime example, which modulate the E3 ligase CRL4CRBN to promote the selective degradation of specific oncogenic proteins like IKZF1/3 in multiple myeloma [6]. This has given rise to the field of Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs), which are heterobifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to neo-substrates to induce their degradation [6].

- DUB Inhibitors: DUBs are emerging as promising drug targets. For instance, USP7 is an oncology target that regulates the stability of p53 and other proteins. Selective USP7 inhibitors are in development, and ubiquitinomics provides a powerful tool for profiling their on-target effects and understanding their mechanism of action on a proteome-wide scale [6].

Conclusion The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System, with its intricate E1-E2-E3-DUB enzymatic network, is a cornerstone of cellular regulation. Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics has revolutionized our ability to study this system at a global level, providing unprecedented insights into the scope and dynamics of protein ubiquitination. The continued refinement of protocols—such as optimized SDC lysis, DIA-MS acquisition, and sophisticated computational data analysis—is driving the field toward deeper, more precise, and higher-throughput analyses. As therapeutic interventions targeting the UPS continue to expand beyond proteasome inhibitors to include E3 ligases and DUBs, ubiquitinomics will remain an indispensable platform for target discovery, drug validation, and mechanistic elucidation in both basic research and clinical drug development.

Ubiquitination, once primarily recognized as a degradation signal for the proteasome, is now understood to regulate a diverse array of cellular processes through distinct mechanisms. This post-translational modification involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes [9]. The functional diversity of ubiquitination stems from variations in ubiquitin chain topology—including monoubiquitination and different polyubiquitin linkages—that determine specific biological outcomes [10]. While K48-linked polyubiquitin chains predominantly target substrates for proteasomal degradation, other chain types, particularly K63-linked polyubiquitination, serve crucial non-proteolytic functions in signaling pathways and membrane trafficking [10] [11]. Additionally, monoubiquitination has emerged as an important regulatory mechanism in DNA repair and protein trafficking [10]. These non-degradative ubiquitination forms fundamentally regulate key cellular processes, including innate immune signaling, DNA damage repair, gene expression, and synaptic plasticity in neurons [10] [11].

Advances in mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics, particularly ubiquitinomics approaches, have revolutionized our understanding of these diverse ubiquitin functions by enabling system-wide profiling of ubiquitination events [12] [13]. This application note details experimental frameworks for investigating non-proteolytic ubiquitination, providing researchers with robust methodologies to explore the full functional spectrum of ubiquitin signaling in health and disease.

Key Non-Proteolytic Functions of Ubiquitination

Signaling Regulation Through K63-Linked Ubiquitination

K63-linked polyubiquitin chains serve as critical regulatory scaffolds in multiple signaling pathways, modulating protein-protein interactions and complex formation without triggering degradation [10]. A seminal example is the activation of IκB kinase (IKK) in the NF-κB signaling pathway, where K63-linked ubiquitination creates platforms for recruiting essential signaling components [10]. Similarly, in DNA damage response pathways, K63-linked chains facilitate the assembly of repair complexes at sites of DNA lesions, coordinating critical repair processes [10]. These signaling roles demonstrate how ubiquitin can function analogously to other post-translational modifications like phosphorylation, dynamically regulating protein activity and intermolecular interactions.

Monoubiquitination in Membrane Trafficking and DNA Repair

Monoubiquitination, involving attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule, serves as a key signal for endocytic trafficking and protein sorting decisions [9]. This modification regulates the internalization of cell surface receptors and their subsequent sorting to lysosomes for degradation or recycling. In DNA repair, monoubiquitination of histone variants such as H2A and H2B coordinates the recruitment of repair machinery to damaged chromatin, illustrating how this modification type controls protein localization and complex assembly [10]. The functional outcomes of monoubiquitination contrast sharply with degradative K48-linked ubiquitination, highlighting the remarkable functional diversity encoded within the ubiquitin system.

Ubiquitination in Neuronal Function and Dysfunction

The unique morphology and functional requirements of neurons make them particularly dependent on precise ubiquitin-mediated regulation. At presynaptic terminals, ubiquitination regulates the size of recycling vesicle pools and vesicle release properties through modification of proteins like RIM1, a calcium-dependent priming factor [11]. Postsynaptically, ubiquitination controls the abundance of glutamate receptors and organizers of the postsynaptic density, thereby modulating synaptic strength and plasticity [11]. These mechanisms contribute to learning and memory processes, with proteasome inhibition experiments demonstrating impaired long-term potentiation and memory retention [11]. Notably, dysfunction in ubiquitin-mediated processes is implicated in numerous neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and Huntington's disease, characterized by accumulation of ubiquitin-positive protein aggregates [11].

Table 1: Diverse Functions of Ubiquitination in Cellular Regulation

| Ubiquitination Type | Primary Functions | Key Examples | Biological Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked chains | Proteasomal targeting | Regulation of cell cycle proteins | Protein degradation, homeostasis |

| K63-linked chains | Signaling scaffold | IKK complex activation, DNA repair | Kinase activation, complex assembly |

| Monoubiquitination | Trafficking, DNA repair | Histone modification, receptor endocytosis | Chromatin remodeling, membrane transport |

| Mixed/linked chains | Regulatory functions | Proteasome, translation regulation | Complex signaling integration |

Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitinomics Approaches

Enrichment Strategies for Ubiquitinated Peptides

Comprehensive ubiquitinome profiling requires specialized enrichment techniques to isolate low-abundance ubiquitinated peptides from complex proteomic backgrounds. The most widely adopted method leverages antibodies specific for di-glycine (K-GG) remnants left after tryptic digestion, which recognize the signature Gly-Gly modification on lysine residues where ubiquitin was attached [9] [13]. This approach has been significantly enhanced through optimized sample preparation protocols, including sodium deoxycholate (SDC)-based lysis buffers supplemented with chloroacetamide (CAA) for immediate cysteine protease inactivation, improving ubiquitin site coverage by approximately 38% compared to conventional urea-based methods [13]. Alternative strategies include poly-His tagged ubiquitin systems coupled with nickel-NTA purification and utilization of ubiquitin-binding domains for enrichment, though these methods show varying efficacy in proteome-wide applications [9].

Advanced MS Acquisition and Data Analysis Methods

Data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry has emerged as a transformative technology for ubiquitinomics, overcoming limitations of traditional data-dependent acquisition (DDA) methods. When coupled with deep neural network-based processing using tools like DIA-NN, DIA-MS more than triples identification numbers to approximately 70,000 ubiquitinated peptides in single runs while significantly improving quantitative precision and reproducibility [13]. This approach enables highly robust ubiquitinome profiling even in large sample series, with median coefficients of variation below 10% for quantified K-GG peptides [13]. The method's power is further enhanced through "library-free" analysis modes that eliminate the need for extensive spectral library generation while maintaining high identification confidence through rigorous false discovery rate control specifically optimized for ubiquitin remnant peptides [13].

Table 2: Comparison of MS Methods for Ubiquitinome Profiling

| Parameter | Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical K-GG peptide IDs | ~21,000-30,000 | ~68,000-70,000 |

| Quantitative precision (median CV) | 15-20% | ~10% |

| Missing values in replicates | ~50% | Minimal (<5%) |

| Required protein input | 500 μg - 4 mg | 31 μg - 2 mg |

| Throughput | Moderate | High |

| Optimal processing software | MaxQuant | DIA-NN |

Functional Applications in Drug Discovery and Target Validation

Ubiquitinomics approaches have proven particularly valuable in drug discovery, especially for characterizing targeted protein degradation platforms such as molecular glue degraders (MGDs) and proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs). High-throughput proteomic screening of cereblon (CRBN)-recruiting MGDs has revealed an extensive neosubstrate landscape, identifying highly selective degraders for targets including KDM4B, G3BP2, and VCL [14]. Integrated proteomics and ubiquitinomics profiling enables comprehensive mode-of-action studies by simultaneously tracking ubiquitination changes and consequent protein abundance shifts following treatment with deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors or E3 ligase modulators [13]. This approach was powerfully demonstrated in studies of USP7 inhibition, where time-resolved analysis revealed that while ubiquitination of hundreds of proteins increased within minutes, only a small fraction underwent degradation, effectively distinguishing degradative from non-degradative ubiquitination events [13].

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitinomics

Optimized Sample Preparation for Ubiquitinome Profiling

Protocol: SDC-Based Lysis and Digestion for Ubiquitinomics

Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in SDC buffer (4% SDC, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 40 mM chloroacetamide) followed by immediate boiling at 95°C for 10 minutes to inactivate ubiquitin proteases [13].

Protein Digestion: Digest proteins using trypsin (1:50 enzyme-to-protein ratio) overnight at 37°C after diluting SDC concentration to 1% to prevent interference [13].

Peptide Cleanup: Acidify digests with trifluoroacetic acid (final 1%), precipitate SDC by centrifugation, and desalt supernatants using C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges [13].

K-GG Peptide Enrichment: Incubate purified peptides with anti-K-GG antibody-conjugated beads for 4-16 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation. Wash beads extensively with ice-cold PBS before eluting with 0.1% TFA [13].

This protocol typically yields 38% more K-GG identifications compared to urea-based methods with excellent enrichment specificity and reproducibility [13].

DIA-MS Acquisition Parameters for Ubiquitinomics

Method: DIA-MS for Comprehensive Ubiquitinome Profiling

LC Conditions: 75-125 min nanoLC gradients using C18 columns (75 μm × 25 cm) with acetonitrile gradients from 2-30% in 0.1% formic acid [13].

MS Instrument Setup: High-resolution tandem mass spectrometer (Q-Exactive Orbitrap or similar) operated in DIA mode [13].

DIA Settings: 30-60 variable-width windows covering 400-1000 m/z range; MS1 resolution: 120,000; MS2 resolution: 30,000; normalized collision energy: 25-30% [13].

Data Processing: Analyze raw files using DIA-NN in "library-free" mode against appropriate protein sequence databases with K-GG modification specified as variable modification [13].

This method typically identifies >68,000 ubiquitination sites with median CV <10% across replicates, enabling robust quantitative comparisons across experimental conditions [13].

Visualization of Ubiquitin Signaling and Experimental Workflows

Non-Degradative Ubiquitin Signaling Pathways

Non-Degradative Ubiquitin Signaling Pathways

Ubiquitinomics Experimental Workflow

Ubiquitinomics Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitinomics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitinomics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffers | SDC buffer (4% SDC, 100 mM Tris-HCl, 40 mM CAA) | Optimal protein extraction for ubiquitinomics [13] |

| Protease Inhibitors | MG-132, Bortezomib | Proteasome inhibition to preserve ubiquitinated proteins [13] |

| Enrichment Reagents | Anti-K-GG antibody beads | Immunoaffinity purification of ubiquitin remnant peptides [13] |

| MS Instruments | Q-Exactive Orbitrap, timsTOF | High-resolution mass spectrometry for ubiquitinome profiling [14] [13] |

| Data Processing | DIA-NN, MaxQuant | Software for identification/quantification of ubiquitin sites [13] |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | Molecular glue degraders, PROTACs | Tools to manipulate cellular ubiquitination [14] |

| DUB Inhibitors | USP7 inhibitors | Investigate deubiquitination effects on ubiquitinome [13] |

Ubiquitination is a fundamental post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotic cells, including protein degradation, DNA repair, cell signaling, and immune responses [15] [16]. This modification involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin—a small 76-amino acid protein—to substrate proteins via a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [15] [17]. The system is dynamically reversed by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), creating a reversible regulatory mechanism comparable to other PTMs like phosphorylation [16] [18]. The human genome encodes approximately 2 E1 enzymes, 60 E2 enzymes, over 600 E3 ligases, and more than 100 DUBs, enabling exquisite specificity in substrate selection and regulatory control [16] [18].

The complexity of ubiquitin signaling extends beyond simple monoubiquitination. Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminus that can serve as attachment points for additional ubiquitin molecules, forming polyubiquitin chains of various architectures and lengths [16] [19]. These chains can be homotypic (single linkage type), heterotypic (mixed linkages), or branched (multiple modifications on a single ubiquitin molecule), creating a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that determines functional outcomes [16] [19]. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling is further expanded by non-canonical ubiquitination on non-lysine residues and the existence of unanchored polyubiquitin chains not attached to substrates [15] [16]. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has emerged as a powerful technology for deciphering this complex ubiquitin code, enabling system-wide profiling of ubiquitination events under physiological and pathological conditions [16] [13].

The Expanding Landscape of Ubiquitin Modifications

Canonical Ubiquitination

Canonical ubiquitination involves the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on the substrate protein [15] [17]. This process can result in either monoubiquitination (single ubiquitin modification) or multi-monoubiquitination (multiple single ubiquitins on different lysines) [16]. When additional ubiquitin molecules are conjugated to one of the seven lysine residues or the N-terminal methionine of the previously attached ubiquitin, polyubiquitin chains are formed [16] [19].

The specific linkage type within polyubiquitin chains determines the functional consequence for the modified substrate. For instance, K48-linked chains primarily target proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains typically mediate non-proteolytic signaling in processes such as DNA repair, inflammation, and endocytosis [19] [20]. Other linkages, including K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33, have been associated with diverse cellular functions, although their roles are less characterized [16]. The combinatorial complexity increases further with the formation of mixed linkage chains and branched ubiquitin chains, where a single ubiquitin molecule is modified at multiple sites [16] [19].

Table 1: Major Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Cellular Functions | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | Proteasomal degradation, cell cycle progression | Compact structure targeting to proteasome |

| K63 | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis, kinase activation | Extended conformation facilitating signaling |

| K11 | Proteasomal degradation, cell cycle regulation (mitosis) | Mixed features of K48 and K63 |

| K29 | Proteasomal degradation (with K48 in branched chains) | Less characterized, implicated in proteolysis |

| K33 | Kinase regulation, intracellular trafficking | Role in endosomal sorting |

| K6 | DNA damage response, mitophagy | Implicated in Parkinson's disease pathway |

| K27 | Immune signaling, inflammatory response | Key regulator of innate immunity |

| M1 (linear) | NF-κB activation, inflammatory signaling | Generated by LUBAC complex |

Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

Beyond canonical lysine ubiquitination, emerging research has established the existence and functional significance of non-canonical ubiquitination on non-lysine residues [15]. These modifications expand the ubiquitin code by employing chemical bonds distinct from the conventional isopeptide linkage:

N-terminal ubiquitination: Ubiquitin is conjugated to the α-amino group of a protein's N-terminus via a peptide bond [15]. This modification has been demonstrated to target proteins such as Ngn2, p14ARF, and p21 for degradation and can distinctly alter the catalytic activity of deubiquitinating enzymes like UCHL1 and UCHL5 [15]. The E2 enzyme UBE2W has been specifically implicated in mediating N-terminal ubiquitination due to its flexible C-terminus that enables selective targeting of α-amino groups [15].

Cysteine, Serine, and Threonine ubiquitination: These modifications occur through thioester (cysteine) or oxyester (serine/threonine) bonds [15] [16]. While less common than lysine ubiquitination, they play significant non-proteolytic signaling roles. For example, cysteine ubiquitination of MHC-I by viral E3 ligases can mediate immune evasion [16].

Pathogen-mediated unconventional ubiquitination: The bacterium Legionella pneumophila secretes effector proteins (SdeA, SdeB, SdeC, SidE) that catalyze phosphoribosyl (PR)-linked serine ubiquitination, completely bypassing the host E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade [15]. This unique form of ubiquitination involves conjugation of ubiquitin's Arg42 to substrate serine residues via a phosphoribosyl linker and remodels host cellular processes to promote bacterial infectivity [15].

Table 2: Types of Non-Canonical Ubiquitination and Their Characteristics

| Modification Type | Bond Formation | Functional Examples | Enzymatic Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-terminal ubiquitination | Peptide bond to α-amino group | Targets p21, p14ARF for degradation; modulates DUB activity | UBE2W E2 enzyme specialized for N-termini |

| Cysteine ubiquitination | Thioester bond | Non-proteolytic signaling; MHC-I regulation by viral ligases | Conventional E1-E2-E3 cascade |

| Serine/Threonine ubiquitination | Oxyester bond | Downregulation of BST-2/tetherin by HIV-1 Vpu | Conventional E1-E2-E3 cascade |

| PR-serine ubiquitination | Phosphoribosyl linker | Host protein modification by Legionella pneumophila | SidE family effectors (single enzyme) |

Branched Ubiquitin Chains and Chain Plasticity

Branched ubiquitin chains, wherein a single ubiquitin molecule is modified at multiple sites, represent an additional layer of complexity in the ubiquitin code [19]. These architectures can include bifurcations at consecutive lysines (K6/K11, K27/K29, K29/K33) or more complex branching patterns (K11/K48, K48/K63) [16] [19]. Initially, branched chains were thought to be less effective at promoting protein degradation compared to homotypic chains, but recent evidence challenges this view [19]. For instance, K11/K48 branched chains produced by the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) are particularly efficient at triggering proteasomal degradation of cell cycle regulators [19].

The plasticity of ubiquitin chain architecture enables dynamic reprogramming of ubiquitin signaling in response to cellular stimuli. For example, cancer cells can strategically manipulate K63-linked chains to stabilize DNA repair factors while concurrently inhibiting K48-mediated degradation of survival proteins, creating adaptive resistance mechanisms to therapies like radiotherapy [20]. This rewiring of ubiquitin signaling manifests through multiple mechanisms, including DNA repair manipulation and metabolic adaptation, highlighting the functional significance of understanding chain topology in pathological contexts [20].

Analytical Challenges in Ubiquitinomics

The structural diversity of ubiquitin modifications presents significant challenges for comprehensive analysis. Conventional bottom-up proteomics approaches, which involve tryptic digestion of proteins followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), have proven highly successful for identifying ubiquitination sites but inevitably collapse information about polyubiquitin chain topology [16] [19]. During trypsin digestion, the ubiquitin molecule is trimmed to a diglycine (Gly-Gly) remnant that remains attached to the modified lysine, adding a monoisotopic mass of 114.043 Da—a signature used for site identification [17] [13]. While this approach enables large-scale mapping of ubiquitination sites, it eliminates the connectivity information between ubiquitin molecules in chains.

Middle-down and top-down strategies have been developed to preserve information about ubiquitin chain architecture [19]. The Ubiquitin Chain Enrichment Middle-down Mass Spectrometry (UbiChEM-MS) approach employs minimal trypsinolysis under nondenaturing conditions, which cleaves ubiquitin only between Arg74 and Gly75, yielding an intact Ub1-74 fragment [19]. When a branch point is present within the ubiquitin chain, the ubiquitin moiety bearing the branch point will be modified with two Gly-Gly modifications (2xGG-Ub1-74), enabling detection and characterization of multiple modifications on a single ubiquitin molecule [19]. This method has been successfully applied to detect branched ubiquitin chains in human cells, revealing that approximately 1% of chains isolated with tandem ubiquitin binding entities (TUBEs) contain branch points, increasing to ~4% after proteasome inhibition [19].

Additional challenges in ubiquitinomics include the typically low stoichiometry of ubiquitination sites, the lability of certain non-canonical linkages (particularly oxyester bonds), and the need to distinguish ubiquitin modification sites from other lysine modifications such as acetylation or SUMOylation [15] [16]. Furthermore, the dynamic nature of ubiquitination, with continuous attachment and removal by DUBs, necessitates careful experimental design including the use of proteasome inhibitors or DUB inhibitors to capture transient ubiquitination events [13].

Advanced Mass Spectrometry Approaches for Ubiquitinomics

Sample Preparation and Enrichment Strategies

Effective ubiquitinomics relies on specialized sample preparation methods to enrich low-abundance ubiquitinated peptides from complex proteomic backgrounds. The most common approach involves immunoaffinity purification using antibodies specific for the diglycine remnant left on modified lysines after tryptic digestion [13] [21]. Recent methodological improvements have significantly enhanced the sensitivity and specificity of this enrichment process.

A key advancement is the implementation of sodium deoxycholate (SDC)-based lysis protocols supplemented with chloroacetamide (CAA) for immediate cysteine alkylation [13]. Compared to conventional urea-based buffers, SDC lysis increases K-GG peptide identification by approximately 38% (26,756 vs. 19,403 peptides from HCT116 cells) while maintaining high enrichment specificity [13]. This protocol rapidly inactivates cysteine-dependent DUBs through immediate boiling and alkylation, better preserving the native ubiquitinome landscape [13]. Additionally, CAA prevents unspecific di-carbamidomethylation of lysine residues that can mimic K-GG peptides—an artifact observed with iodoacetamide that complicates data interpretation [13].

For specialized applications focusing on specific ubiquitin chain types, ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) such as tandem ubiquitin binding entities (TUBEs) or linkage-selective UBDs like the K29-selective NZF1 domain from TRABID can be employed [19]. These tools enable enrichment of particular chain architectures before middle-down MS analysis, facilitating characterization of branched ubiquitin chains that are inaccessible to conventional bottom-up approaches [19].

Data-Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry

Data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry has emerged as a transformative technology for ubiquitinomics, offering significant advantages over traditional data-dependent acquisition (DDA) methods [13] [14]. While DDA typically identifies 20,000-30,000 K-GG peptides with substantial missing values across replicates, DIA-MS more than triples identification to approximately 70,000 ubiquitinated peptides in single MS runs while dramatically improving quantitative precision and reproducibility [13].

The power of DIA-MS is further enhanced when coupled with deep neural network-based data processing tools like DIA-NN [13]. This combination achieves a median coefficient of variation (CV) of ~10% for quantified K-GG peptides, with over 68,000 peptides consistently quantified across replicates [13]. The method demonstrates excellent quantitative accuracy across a wide dynamic range, as validated by spike-in experiments with synthetic K-GG peptides at different concentrations [13]. This level of performance enables complex time-resolved studies, such as monitoring ubiquitination dynamics following USP7 inhibition at multiple time points, capturing both immediate ubiquitination changes and subsequent protein abundance alterations [13].

The high throughput and reproducibility of DIA-MS make it particularly suitable for large-scale screening applications, such as profiling molecular glue degrader libraries against hundreds of compounds [14]. In such studies, DIA-MS can quantify over 10,000 protein groups with median CVs of ~6% across replicates, enabling robust statistical identification of neosubstrates based on both ubiquitination increases and protein degradation [14].

Integrated Proteomics and Ubiquitinomics Profiling

A powerful application of modern ubiquitinomics is the simultaneous profiling of ubiquitination changes and corresponding protein abundance alterations [13] [14]. This integrated approach distinguishes regulatory ubiquitination events that lead to protein degradation from non-degradative ubiquitination that modulates protein function, localization, or interactions.

In practice, this involves parallel processing of samples for global proteomics (measuring protein abundance) and ubiquitinomics (measuring ubiquitination sites) [14]. Following treatment with perturbations such as DUB inhibitors or molecular glue degraders, proteins showing increased ubiquitination without corresponding degradation likely undergo non-proteolytic regulatory ubiquitination [13]. Conversely, proteins displaying both increased ubiquitination and decreased abundance represent candidates for degradative ubiquitination [14]. This distinction is critical for understanding the mechanistic consequences of ubiquitin signaling perturbations and for validating putative drug targets.

For example, in studies of USP7 inhibition, hundreds of proteins show increased ubiquitination within minutes, but only a small fraction subsequently undergo degradation, highlighting that most ubiquitination events serve non-proteolytic functions [13]. Similarly, in molecular glue degrader screens, this integrated approach can identify bona fide neosubstrates based on rapid ubiquitination following treatment, followed by CRL-dependent protein degradation that is rescued by NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibition [14].

Experimental Protocols for Comprehensive Ubiquitinome Analysis

Protocol 1: SDC-Based Sample Preparation for Deep Ubiquitinome Profiling

This protocol describes an optimized workflow for preparing samples for ubiquitinomics analysis, achieving identification of >30,000 K-GG peptides from 2 mg of protein input with high reproducibility [13].

Reagents and Materials

- Lysis Buffer: 1% SDC in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 100 mM chloroacetamide (CAA), 40 mM 2-chloroacetamide

- PBS (phosphate-buffered saline)

- Protease inhibitor cocktail

- Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail

- Deubiquitinase inhibitor (optional)

- BCA protein assay kit

- sequencing-grade modified trypsin

- PreOmics iST binding buffer

- anti-K-ε-GG antibody-conjugated beads

- Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)

- StageTips with C18 material

Procedure

- Cell Lysis: Aspirate culture medium and wash cells twice with ice-cold PBS. Add SDC lysis buffer (1-2 mL per 10⁷ cells) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Immediately scrape cells and transfer to preheated (95°C) microcentrifuge tubes. Incubate at 95°C for 10 minutes with shaking at 1000 rpm [13].

- Protein Quantification: Cool samples to room temperature and determine protein concentration using BCA assay. Use 2 mg protein per condition for optimal results, with minimum 500 µg for limited samples [13].

- Protein Digestion: Adjust protein concentration to 1 mg/mL with lysis buffer. Add trypsin at 1:50 (w/w) enzyme-to-protein ratio and incubate overnight at 37°C with shaking [13].

- Peptide Cleanup: Acidify samples to pH < 3 with TFA (final concentration 1%). Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes to pellet SDC. Transfer supernatant to new tubes and desalt using StageTips with C18 material according to manufacturer's instructions [13].

- K-ε-GG Peptide Enrichment: Resuspend dried peptides in PreOmics iST binding buffer. Incubate with anti-K-ε-GG antibody-conjugated beads for 2 hours at room temperature with gentle rotation. Wash beads three times with binding buffer and twice with water [13].

- Peptide Elution: Elute K-ε-GG peptides with 0.2% TFA. Dry peptides in a speedvac and store at -20°C until MS analysis [13].

Protocol 2: UbiChEM-MS for Branched Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

This protocol enables detection and characterization of branched ubiquitin chains that are inaccessible to conventional bottom-up proteomics [19].

Reagents and Materials

- TUBEs (tandem ubiquitin-binding entities) or linkage-selective UBDs (e.g., NZF1 for K29 chains)

- HaloLink resin (Promega)

- Binding buffer: 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.05% IGEPAL CA-630, pH 7.5

- Minimal buffer: 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5

- Sequencing-grade modified trypsin

- Acetic acid

- C18 Sep-Pak columns (Waters)

Procedure

- UBD Resin Preparation: Couple HaloTag-UBD fusion protein to HaloLink resin according to manufacturer's instructions. Use 100 µL TUBE resin or 200 µL NZF1 resin per sample [19].

- Ubiquitin Chain Enrichment: Incubate 45 mg cell lysate with UBD resin overnight at 4°C with rotation. Pellet resin at 800 × g for 2 minutes and discard supernatant. Wash resin three times with 2 mL binding buffer and twice with 2 mL minimal buffer [19].

- On-Resin Minimal Trypsinolysis: Resuspend resin in 100 µL minimal buffer. Add trypsin at empirically determined ratio (typically 1:20 to 1:100 enzyme-to-substrate ratio) and incubate at room temperature for 16 hours [19].

- Reaction Termination and Peptide Extraction: Acidify samples to pH 2 with acetic acid to deactivate trypsin. Incubate at 4°C for 15-30 minutes, then centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 5 minutes. Transfer supernatant to new tubes [19].

- Sample Desalting: Concentrate supernatant 5-7-fold using a speedvac. Load onto C18 Sep-Pak column pre-equilibrated with 0.1% TFA. Wash with 3 mL equilibration solution, then elute with step gradients of 10-60% acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA. Lyophilize fractions containing ubiquitin species [19].

- Middle-Down MS Analysis: Resuspend samples in water/acetonitrile/acetic acid (45:45:10) and analyze by high-resolution mass spectrometry (e.g., Orbitrap Fusion) with electron-transfer dissociation (ETD) capability for branched chain characterization [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitinomics Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Tools | anti-K-ε-GG antibodies | Immunoaffinity purification of ubiquitinated peptides for bottom-up ubiquitinomics |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins under native conditions for functional studies | |

| Linkage-selective UBDs (e.g., NZF1, UBAN) | Selective isolation of specific ubiquitin chain types (K29, K63, M1) | |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Stable isotope-labeled ubiquitin | Internal standard for quantitative ubiquitinomics |

| Synthetic K-GG peptides | Spike-in standards for quantification accuracy assessment | |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Proteasome inhibitors (MG-132, bortezomib) | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins by blocking degradation |

| DUB inhibitors (PR-619, USP7 inhibitors) | Capture transient ubiquitination by preventing deubiquitination | |

| NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor (MLN4924) | Validate CRL-dependent ubiquitination mechanisms | |

| Specialized MS Reagents | HaloTag fusion vectors for UBD expression | Customizable ubiquitin chain enrichment platforms |

| Chloroacetamide (CAA) | Alkylating agent that prevents artifacts in ubiquitinomics |

Data Visualization and Analysis

The following diagrams illustrate key ubiquitin signaling pathways and experimental workflows described in this application note.

Diagram 1: The Expanding Ubiquitin Code. This diagram illustrates the structural complexity of ubiquitin modifications, including canonical lysine ubiquitination with major linkage types, non-canonical ubiquitination on various residues, and diverse chain architectures.

Diagram 2: Ubiquitinomics Workflow from Sample to Insight. This diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow for comprehensive ubiquitinome analysis, highlighting critical steps from sample preparation through data integration and biological application.

The complexity of the ubiquitin code—encompassing canonical and non-canonical modifications alongside diverse polyubiquitin chain topologies—represents a sophisticated regulatory system governing virtually all cellular processes. Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics has evolved into a powerful technology for deciphering this complexity, enabling researchers to map ubiquitination events on a proteome-wide scale with unprecedented depth and precision. The methodologies and applications described in this document provide a framework for leveraging these advances to accelerate drug discovery, identify novel therapeutic targets, and elucidate mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. As ubiquitinomics technologies continue to mature, particularly with the adoption of DIA-MS and integrated multi-omics approaches, our ability to interpret the ubiquitin code and harness its therapeutic potential will undoubtedly expand, opening new frontiers in biomedical research and precision medicine.

Mass Spectrometry as a Discovery Engine for System-Wide Ubiquitinome Profiling

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based ubiquitinomics provides a system-level understanding of ubiquitin signaling, a process vital for regulating intracellular events like cell cycle progression, selective autophagy, and response to growth factors [22]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) comprises approximately 750 enzymes that mediate the attachment and cleavage of ubiquitin from target proteins [22]. Dysregulation of this system can contribute to carcinogenesis, making various UPS components, such as deubiquitinases (DUBs) and E3 ligases, active targets for anticancer drug development [22]. Modern ubiquitinomics relies on immunoaffinity purification and MS-based detection of diglycine-modified peptides (K-GG), which are generated by tryptic digestion of ubiquitin-modified proteins, enabling global profiling of ubiquitination events [22].

Optimized Protocols for Ubiquitinome Profiling

Sample Preparation and Lysis

Robust sample preparation is foundational for deep ubiquitinome coverage. An improved sodium deoxycholate (SDC)-based lysis protocol has been demonstrated to significantly boost the yield of K-GG peptides compared to conventional urea-based methods [22].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cell pellets or tissue in an ice-cold buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl and 0.5% SDC. For tissue, a buffer with 100 mM Tris HCl, 12 mM SDC, and 12 mM sodium N-lauroylsarcosinate is effective.

- Immediate Protease Inactivation: Supplement the SDC buffer with chloroacetamide (CAA) and immediately boil samples post-lysis. CAA rapidly alkylates and inactivates cysteine ubiquitin proteases without causing non-specific di-carbamidomethylation of lysine residues, which can mimic K-GG peptides.

- Protein Processing: Reduce proteins with 5 mM DTT (30 min, 50°C), alkylate with 10 mM iodoacetamide (15 min, in the dark), and digest using Lys-C (4 hours) followed by trypsin (overnight at 30°C).

- Peptide Clean-up: Precipitate detergents with 0.5% TFA and centrifugate before collecting the peptide-containing supernatant.

This optimized SDC protocol yielded 38% more K-GG peptides than urea buffer and significantly improved reproducibility and quantitative precision [22].

Peptide Enrichment and Fractionation

To isolate low-abundance ubiquitin remnants, immunoaffinity purification (IP) is employed using ubiquitin remnant motif antibodies [23].

Key Protocol Steps [23]:

- Crude Fractionation: Prior to IP, fractionate tryptic peptides using high-pH reverse-phase C18 chromatography. For ~10 mg protein digest, use a column with 0.5 g of C18 material. Elute peptides into three distinct fractions using 10 mM ammonium formate with 7%, 13.5%, and 50% acetonitrile, respectively.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate peptide fractions with antibody-conjugated beads for two hours at 4°C. A sequential incubation with two fresh batches of beads can increase yield.

- Wash and Elute: Wash beads thoroughly with ice-cold IAP buffer and water. Elute bound peptides with 0.15% TFA, desalt using C18 stage tips, and dry via vacuum centrifugation.

This fractionation approach, combined with sequential IP, helps manage sample complexity and enables the identification of over 23,000 unique diGly peptides from a single sample of HeLa cells [23].

Mass Spectrometry Acquisition and Data Analysis

Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) coupled with advanced data processing has emerged as a superior method for ubiquitinomics, offering greater depth, robustness, and quantitative precision compared to traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) [22].

Key Protocol Parameters [22]:

- MS Acquisition: Utilize a sensitive nanoflow LC-MS/MS system. For DIA, specific MS methods are optimized for ubiquitinomics (see Supplementary Data 4 in [22]).

- Data Processing: Process DIA data using DIA-NN software in "library-free" mode, which uses a deep neural network-based algorithm specifically optimized for the confident identification of modified peptides like K-GG peptides. This approach can quantify over 68,000 K-GG peptides in a single run, more than tripling the numbers achievable by DDA [22].

- Confidence Assessment: DIA-NN employs a rigorous false discovery rate (FDR) determination for K-GG peptides, with validation confirming comparable confidence to DDA workflows [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Lysis Buffer Performance for Ubiquitinomics

| Parameter | SDC-Based Lysis Buffer | Conventional Urea-Based Buffer |

|---|---|---|

| Average K-GG Peptide Yield | 26,756 peptides [22] | 19,403 peptides [22] |

| Key Additive | Chloroacetamide (CAA) [22] | Iodoacetamide [22] |

| Reproducibility | Significantly improved robustness and precision [22] | Lower reproducibility and precision [22] |

| Specificity Concern | No unspecific di-carbamidomethylation [22] | Potential for di-carbamidomethylation mimicking K-GG [22] |

Quantitative Performance and Data Quality

The integration of SDC-based lysis with DIA-MS and DIA-NN processing represents a state-of-the-art workflow that dramatically enhances the scope and reliability of ubiquitinome profiling.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of MS Acquisition Methods in Ubiquitinomics

| Performance Metric | Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) |

|---|---|---|

| Average K-GG Peptides ID (Single Run) | 21,434 peptides [22] | 68,429 peptides [22] |

| Quantitative Precision (Median CV) | Higher variability [22] | ~10% [22] |

| Missing Values in Replicates | ~50% of IDs have missing values [22] | 68,057 peptides quantified in ≥3 of 4 replicates [22] |

| Throughput & Robustness | Suitable for smaller studies; susceptible to run-to-run variability [22] | Ideal for large sample series; high robustness [22] |

This optimized workflow enables the simultaneous recording of ubiquitination changes and consequent abundance changes for more than 8,000 proteins at high temporal resolution, providing a powerful tool for dynamic studies [22].

Application in Drug Discovery and Systems Biology

The power of deep, time-resolved ubiquitinome profiling is exemplified in the functional investigation of deubiquitinases (DUBs), such as the oncology target USP7 [22].

Application Protocol:

- Perturbation: Treat cells (e.g., HCT116) with a selective USP7 inhibitor.

- Time-Resolved Profiling: Conduct simultaneous ubiquitinome and proteome profiling at multiple time points (e.g., minutes to hours) post-inhibition using the described DIA-MS workflow.

- Data Integration: Combine the profiles of ubiquitinated peptides with the corresponding protein abundance data to distinguish ubiquitination events that lead to protein degradation from those that are non-degradative.

This approach revealed that upon USP7 inhibition, hundreds of proteins showed increased ubiquitination within minutes, but only a small fraction of those were subsequently degraded [22]. This dissects the scope of USP7 action, demonstrating that its primary role may be in non-proteolytic signaling for many substrates, a critical insight for drug mechanism-of-action studies [22]. This method enables rapid and precise mode-of-action profiling for candidate drugs targeting DUBs or ubiquitin ligases [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of a system-wide ubiquitinome study requires a suite of specific reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitinomics

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Antibody | Immunoaffinity purification of K-GG peptides from tryptic digests [22] [23] | Conjugated to protein A agarose beads [23] |

| Sodium Deoxycholate (SDC) | Powerful detergent for efficient protein extraction during cell lysis [22] | Used in optimized lysis buffer with Tris HCl [22] |

| Chloroacetamide (CAA) | Cysteine alkylating agent to rapidly inactivate DUBs during lysis [22] | Preferred over iodoacetamide to avoid lysine artifacts [22] |

| Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) | Isobaric label for multiplexed quantitative proteomics [24] | Enables parallel analysis of 10 samples in a single MS run [24] |

| DIA-NN Software | Deep neural network-based data processing for DIA-MS data [22] | Features a specialized scoring module for confident K-GG peptide ID [22] |

Workflow and Signaling Visualizations

The following diagrams, generated with DOT language, summarize the core experimental workflow and the biological context of ubiquitin signaling. The color palette adheres to the specified guidelines, ensuring sufficient contrast for readability.

Ubiquitinome Profiling Workflow

Ubiquitin Signaling Pathway

Linking Dysregulated Ubiquitin Signaling to Cancer and Neurodegenerative Diseases

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) serves as a critical post-translational regulatory mechanism that governs nearly every cellular process in eukaryotes by controlling protein stability, localization, and functional activity [25] [26]. This sophisticated system involves a coordinated enzymatic cascade whereby ubiquitin—a highly conserved 76-amino acid polypeptide—is covalently attached to substrate proteins via a series of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [27] [25]. The resulting ubiquitin modifications can range from single ubiquitin molecules (monoubiquitination) to complex polyubiquitin chains formed through different lysine linkages within ubiquitin itself, with each topology encoding distinct functional consequences for the modified substrate [26] [28].

Dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling has emerged as a fundamental pathogenic mechanism in diverse human diseases, particularly in cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [27] [26] [29]. In cancer cells, altered ubiquitination patterns can drive oncogenic signaling, cell cycle progression, and metastatic behavior [30] [29]. Conversely, in neurodegenerative diseases, impaired ubiquitin-mediated protein clearance contributes to the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates that characterize conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [27] [26]. Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics has revolutionized our ability to systematically profile these alterations, providing unprecedented insights into disease mechanisms and revealing potential therapeutic targets [13] [25] [28].

Analytical Framework: Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitinomics

Core Methodological Principles

Modern ubiquitinomics relies primarily on anti-diglycine remnant immunoaffinity enrichment techniques, which exploit the characteristic diglycine (K-ε-GG) signature left on trypsinized peptides following ubiquitination [29] [31]. When combined with high-resolution mass spectrometry, this approach enables system-wide identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites with exceptional precision and depth [13] [29]. The field has progressively evolved from data-dependent acquisition (DDA) methods to more advanced data-independent acquisition (DIA) approaches, which significantly enhance reproducibility, quantification accuracy, and coverage of the ubiquitinome [13].

Recent methodological innovations have substantially improved the sensitivity and scope of ubiquitinomics analyses. The introduction of sodium deoxycholate (SDC)-based lysis protocols with immediate boiling and chloroacetamide alkylation has demonstrated a 38% increase in identified K-ε-GG peptides compared to conventional urea-based methods, while simultaneously improving quantitative reproducibility [13]. When coupled with deep neural network-based data processing tools like DIA-NN, researchers can now routinely identify >70,000 ubiquitinated peptides in single LC-MS runs—more than triple the coverage achievable with DDA methods—while maintaining excellent quantitative precision (median CV ≈10%) [13].

Advanced Enrichment and Quantification Strategies

For specialized applications, tandem ubiquitin binding entities (TUBEs) offer significant advantages for studying labile ubiquitination events. TUBEs provide up to 1,000-fold increased affinity for polyubiquitin chains compared to single ubiquitin-binding domains and protect ubiquitinated proteins from both proteasomal degradation and deubiquitinating enzyme activity [31]. This approach is particularly valuable for investigating ubiquitination in neurodegenerative contexts, where protein aggregates often impede conventional analysis methods [27] [31].

Quantitative ubiquitinomics has been transformed by stable isotope labeling and label-free quantification approaches that enable precise measurement of ubiquitination dynamics across multiple cellular conditions [25] [29]. These techniques are especially powerful when combined with temporal resolution studies, allowing researchers to distinguish regulatory ubiquitination events that lead to protein degradation from those mediating non-proteolytic functions [13]. The resulting datasets provide unprecedented insights into the kinetics and functional consequences of ubiquitin signaling in pathological states.

Ubiquitin Signaling Dysregulation in Cancer

Global Ubiquitinome Alterations in Cancer Pathogenesis

Comprehensive ubiquitinome profiling has revealed extensive reprogramming of ubiquitination networks in human cancers. A system-wide analysis of protein acetylation and ubiquitination in human cancer cells identified more than 5,000 ubiquitination sites and 1,600 acetylation sites, with 236 lysine residues across 141 proteins subject to both modifications—suggesting complex cross-regulatory mechanisms in oncogenesis [30]. Notably, motif analysis revealed glutamic acid (E) highly enriched at the -1 position for acetylation sites, while ubiquitination sites displayed more dispersed amino acid distributions, indicating distinct sequence constraints for these modifications [30].

Pathway analysis of cancer ubiquitinomes has consistently identified protein translational control pathways as key hubs of dysregulated ubiquitination. Specifically, the eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (EIF2) signaling pathway and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis pathway emerge as significantly enriched in cancer cells, highlighting the central role of UPS dysfunction in malignant transformation [30]. These global alterations represent potentially targetable vulnerabilities for cancer therapy.

Metastasis-Associated Ubiquitination Events

Comparative ubiquitinome profiling of human primary and metastatic colon adenocarcinoma tissues has identified distinct ubiquitination patterns associated with disease progression [29]. This research quantified 375 differentially regulated ubiquitination sites across 341 proteins between primary and metastatic tissues, with 132 sites (127 proteins) upregulated and 243 sites (214 proteins) downregulated in metastases [29]. Bioinformatic analysis revealed pronounced enrichment of metastasis-associated ubiquitination events in RNA transport and cell cycle regulation pathways, suggesting fundamental reprogramming of these processes during cancer dissemination.

Table 1: Ubiquitination Changes in Human Primary vs. Metastatic Colon Adenocarcinoma Tissues

| Regulation | Number of Ubiquitination Sites | Number of Proteins | Key Enriched Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | 132 | 127 | RNA transport, Cell cycle |

| Downregulated | 243 | 214 | Metabolic pathways, Proteolysis |

Among the most significantly altered targets, cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) exhibited disease-stage-dependent ubiquitination patterns, suggesting that modified ubiquitination of this central cell cycle regulator may serve as a pro-metastatic factor in colon adenocarcinoma [29]. These findings illustrate how ubiquitinomics can identify functionally important regulatory nodes in cancer progression.

Therapeutic Targeting of Ubiquitin Signaling in Cancer

The druggability of the ubiquitin system is exemplified by ongoing efforts to target deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) such as USP7, which regulates the stability of key oncoproteins and tumor suppressors including p53 [13]. Time-resolved ubiquitinome profiling following USP7 inhibition has enabled comprehensive mapping of USP7 substrates, revealing that hundreds of proteins show increased ubiquitination within minutes of inhibitor treatment [13]. Importantly, simultaneous monitoring of protein abundance demonstrated that only a fraction of these ubiquitination events lead to degradation, highlighting the dual role of ubiquitination in proteolytic and non-proteolytic signaling [13].

These findings underscore the potential of ubiquitinomics for mode-of-action studies of DUB and ubiquitin ligase inhibitors, facilitating rapid characterization of candidate therapeutics at unprecedented precision and throughput [13]. The ability to distinguish degradative from non-degradative ubiquitination events provides critical insights for drug development, particularly for targeted protein degradation approaches that are transforming oncology therapeutics.

Ubiquitin Signaling Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Impaired Protein Quality Control in Neurodegeneration

In neurodegenerative diseases, ubiquitin signaling is primarily associated with protein quality control mechanisms that eliminate aberrant proteins which form aggregates fatal to post-mitotic neurons [27]. The two main catabolic pathways—the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy-lysosomal pathway (ALP)—are interconnected systems that rely on ubiquitin signaling to target proteins for degradation [27]. The UPS predominantly degrades soluble ubiquitinated proteins through the 26S proteasome, while autophagy efficiently clears larger protein aggregates through a selective process called aggrephagy [27]. Both systems typically decline with aging, creating a permissive environment for toxic protein accumulation in age-associated neurodegenerative disorders [27].

The pathological hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases is the presence of ubiquitin-positive inclusions, such as Lewy bodies in Parkinson's disease (primarily composed of α-synuclein) and various tau-containing aggregates in Alzheimer's disease [27] [26]. These deposits represent failed cellular quality control and reflect either overwhelming production of aggregation-prone proteins or progressive failure of ubiquitin-mediated clearance mechanisms—most likely a combination of both factors [27] [26].

Genetic Evidence Linking UPS Components to Neurodegeneration

Strong genetic evidence supports the central role of ubiquitin signaling dysfunction in neurodegenerative pathogenesis. Mutations in several E3 ubiquitin ligases, including Parkin (associated with autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinson's disease), directly impair ubiquitin signaling and protein quality control [27] [26]. Similarly, mutations in genes encoding ubiquitin-binding proteins such as ubiquilin have been linked to neurodegenerative processes, though the exact mechanisms remain under investigation [26].

Interestingly, the functional consequences of these mutations extend beyond proteasomal degradation defects. For example, Parkin also regulates mitochondrial quality control through mitophagy and may facilitate the sequestration of toxic proteins into inclusion bodies via K63-linked ubiquitin chains [26]. This complexity highlights the diverse functions of ubiquitin signaling in neuronal homeostasis and the multiple mechanisms through which its disruption can contribute to neurodegeneration.

Compensatory Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities

Contrary to the initial hypothesis that global UPS impairment is a primary driver of neurodegeneration, accumulating evidence suggests that the UPS remains largely operative in many disease models [26]. Instead, neurodegenerative pathologies may involve more selective defects in handling specific aggregation-prone proteins, combined with age-related declines in proteostatic capacity that create vulnerability to protein misfolding [26]. This paradigm shift repositioned the UPS from a dysfunctional system in neurodegeneration to a potentially harnessable therapeutic target for accelerating clearance of disease-linked proteins [26].

Emerging evidence suggests that adaptive cellular responses help alleviate the burden of aggregation-prone proteins to maintain ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis [26]. These compensatory mechanisms represent promising therapeutic avenues, potentially including enhancement of UPS function, stimulation of ubiquitin ligase activity, or modulation of specific DUBs to rebalance ubiquitin signaling in affected neurons [27] [26].

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitinomics

Ubiquitin Remnant Profiling from Tissues

This protocol outlines the comprehensive ubiquitinome analysis of human primary and metastatic colon adenocarcinoma tissues [29], providing a framework for tissue-based ubiquitinomics studies.

Sample Preparation:

- Tissue Lysis: Homogenize frozen tissues (30 mg) in urea-based lysis buffer (8 M urea, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail) using a high-intensity ultrasonic processor on ice [29].

- Protein Extraction: Remove debris by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Collect supernatant and determine protein concentration using a 2D Quant kit [29].

- Trypsin Digestion: Reduce proteins with 10 mM DTT (1 h, 56°C) and alkylate with 30 mM iodoacetamide (45 min, room temperature in darkness). Dilute samples with 100 mM NH₄HCO₃ to reduce urea concentration below 2 M. Digest with trypsin (1:50 w/w ratio overnight, followed by 1:100 ratio for 4 h) [29].

- Peptide Desalting: Load peptides onto Strata-X C18 columns, wash with 0.1% formic acid (FA) + 5% acetonitrile (ACN), and elute with 0.1% FA + 80% ACN. Dry eluates by vacuum centrifugation [29].

Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment:

- Immunoaffinity Purification: Dissolve tryptic peptides in NETN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, pH 8.0) and incubate with anti-K-ε-GG remnant antibody beads (PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit, Cell Signaling Technology) at 4°C overnight with gentle shaking [29].

- Bead Washing: Wash beads four times with NETN buffer and twice with H₂O [29].

- Peptide Elution: Elute bound peptides with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, combine eluates, and dry by vacuum centrifugation [29].

- Sample Cleanup: Desalt peptides using C18 ZipTips per manufacturer's instructions [29].

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatographic Separation: Resuspend peptides in 0.1% FA and load onto a Thermo Scientific UltiMate 3000 UHPLC system with a trap column and analytical column (homemade nanocapillary C18, 75 μm × 25 cm, 3 μm particles) using a 250 nL/min flow rate [29].

- Gradient Elution: Employ a 40-min linear gradient from 5% to 25% buffer B (98% ACN, 0.1% FA), followed by 5 min to 35% B, 2 min to 80% B, 2 min hold at 80% B, and 1 min return to 5% B with 6 min re-equilibration [29].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Ionize peptides using nanoESI and analyze on a Q-Exactive HF X mass spectrometer in DDA mode with the following parameters: MS1 resolution: 60,000; MS2 resolution: 30,000; HCD fragmentation; dynamic exclusion: 30 s [29].

Data Processing:

- Database Searching: Process MS/MS data using MaxQuant (v1.5.2.8) against the SwissProt Human database with trypsin/P specificity allowing two missed cleavages [29].

- PTM Identification: Set carbamidomethylation of cysteine as fixed modification and Gly-Gly modification of lysine plus methionine oxidation as variable modifications [29].

- Quantification: Apply label-free quantification (LFQ) with FDR adjustment to <1% at peptide and protein levels [29].

Advanced DIA-Ubiquitinomics for Dynamic Signaling Studies

This protocol describes a high-resolution, time-resolved ubiquitinomics workflow for capturing ubiquitination dynamics, such as following DUB inhibition [13].

Optimized Sample Preparation:

- SDC-Based Lysis: Lyse cells in SDC buffer (2% sodium deoxycholate, 40 mM chloroacetamide, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) with immediate incubation at 95°C for 5 min to inactivate ubiquitin proteases [13].

- Protein Digestion: Digest proteins directly in SDC buffer using trypsin (1:50 w/w ratio) after diluting SDC concentration below 0.5% to prevent precipitation [13].

- Peptide Cleanup: Acidify digests to pH <2 with trifluoroacetic acid to precipitate SDC, followed by centrifugation and collection of supernatant containing peptides [13].

DIA-MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Utilize a 75-min nanoLC gradient on a reversed-phase column with 1.9 μm C18 particles for high-resolution peptide separation [13].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire MS data in DIA mode with optimized isolation windows (typically 4-8 m/z) covering the full m/z range (350-1800) [13].

- Spectral Libraries: Generate comprehensive spectral libraries either in silico or through fractionated DDA runs for maximum identifications [13].

Data Processing with DIA-NN:

- Library-Free Analysis: Process DIA data using DIA-NN in "library-free" mode against appropriate protein sequence databases [13].

- False Discovery Control: Apply stringent filters to maintain FDR <1% at both peptide and protein levels [13].

- Quantitative Analysis: Leverage DIA-NN's neural network-based quantification for precise measurement of ubiquitination changes across time courses [13].

Essential Research Tools for Ubiquitinomics

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Ubiquitinomics Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Key Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody | Immunoaffinity reagent | Enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides from tryptic digests | Global ubiquitinome profiling from tissues and cells [29] |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Affinity capture reagent | Protection and enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins | Study of labile ubiquitination in neurodegenerative models [31] |

| USP7 Inhibitors | Small molecule probes | Selective inhibition of deubiquitinating enzyme USP7 | Mode-of-action studies and target identification [13] |

| SDC Lysis Buffer | Lysis reagent | Enhanced protein extraction with protease inactivation | Improved ubiquitin site coverage and reproducibility [13] |

| DIA-NN Software | Computational tool | Deep neural network-based DIA data processing | High-sensitivity ubiquitinome identification and quantification [13] |

Visualizing Ubiquitin Signaling Pathways and Methodologies

Ubiquitin Signaling in Health and Disease: This diagram illustrates the ubiquitin conjugation cascade and the divergent functional outcomes of different ubiquitin modifications, highlighting how specific chain topologies direct substrates toward proteasomal degradation, autophagy, or non-degradative signaling—processes dysregulated in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

Ubiquitinomics Experimental Workflow: This diagram outlines the core steps in mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics, from sample preparation to data analysis, highlighting critical methodological options such as SDC lysis, TUBE enrichment, DIA-MS acquisition, and DIA-NN processing that enhance experimental outcomes.

Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics has fundamentally transformed our understanding of ubiquitin signaling dysregulation in human diseases, providing unprecedented system-level insights into the complex role of ubiquitination in both cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. The continuing evolution of methodological approaches—including improved lysis protocols, advanced DIA acquisition strategies, and sophisticated computational tools—promises even deeper characterization of the ubiquitinome in coming years.

For therapeutic development, ubiquitinomics offers powerful capabilities for target identification, mechanism-of-action studies, and biomarker discovery. As the resolution and throughput of these methods continue to improve, we anticipate increasingly comprehensive maps of ubiquitin signaling networks that will illuminate new therapeutic opportunities for modulating the ubiquitin system in disease contexts. The integration of ubiquitinomics with other omics technologies will further enhance our ability to decipher the complex language of ubiquitin signaling and develop targeted interventions for diseases characterized by ubiquitin system dysregulation.

Cutting-Edge Ubiquitinomics Workflows: From Sample to Insight