Monoubiquitination vs. Polyubiquitination: Decoding Functional Consequences for Targeted Therapies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct functional consequences of monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination, two critical protein modifications that govern cellular signaling.

Monoubiquitination vs. Polyubiquitination: Decoding Functional Consequences for Targeted Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct functional consequences of monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination, two critical protein modifications that govern cellular signaling. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms that dictate whether ubiquitination leads to proteasomal degradation or non-proteolytic outcomes like endocytosis and DNA repair. The content delves into advanced methodologies for differentiating ubiquitin signals, addresses common experimental challenges, and presents a comparative framework for validating ubiquitin chain topology and its implications in disease pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention, including the emerging field of PROTACs.

The Ubiquitin Code: Fundamental Mechanisms of Mono- vs. Polyubiquitination

Ubiquitin is a small, 76-amino acid protein found in nearly all eukaryotic tissues, functioning as a critical post-translational modifier that regulates a vast array of cellular processes [1] [2]. Since its discovery in 1975 and the subsequent elucidation of its fundamental functions throughout the 1980s, ubiquitin research has revolutionized our understanding of cellular biology, culminating in the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 for Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose [1] [2]. The ubiquitylation process involves a sophisticated enzymatic cascade that conjugates ubiquitin to substrate proteins, thereby modulating their stability, activity, localization, and interactions [1] [3]. This primer provides an in-depth technical overview of ubiquitin structure, the enzymatic machinery governing its conjugation, and the reversibility of this process, framed within the context of the distinct functional outcomes of monoubiquitination versus polyubiquitination.

Ubiquitin Structure

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Organization

Ubiquitin is a highly conserved 76-residue protein with a molecular mass of approximately 8.6 kDa [1] [2]. Its primary sequence is remarkably stable across evolution, with human and yeast ubiquitin sharing 96% sequence identity, and the human form being 100% identical to that of the sea slug Aplysia [1] [2]. The protein features seven lysine residues (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, and Lys63) and an N-terminal methionine that serve as potential sites for ubiquitin chain formation [2].

The secondary structure of ubiquitin consists of a mixed β-sheet with five strands, approximately 15.8% α-helix content distributed across three helices, and six β-reverse turns [2]. These elements fold into a compact, globular β-grasp fold, forming a stable tertiary structure with a melting point of nearly 100°C [2]. This high stability derives from extensive intra-hydrogen bonding, with no disulfide bonds, metal ions, or cofactors required for structural integrity [2]. The hydrophobic patch centered around Ile44 is particularly critical for recognition by ubiquitin-binding domains in other proteins [2].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of Ubiquitin

| Structural Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Number of Residues | 76 amino acids [1] |

| Molecular Mass | 8.6 kDa [1] [2] |

| Isoelectric Point (pI) | 6.79 [1] |

| Key Residues | 7 Lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and N-terminal Methionine (M1) [1] [2] |

| Secondary Structure | 5 β-strands, 3.5 turns of α-helix (15.8%), short 310 helix (7.9%), 6 β-reverse turns [2] |

| Tertiary Structure | Compact β-grasp fold [2] |

| Stability | Melting point ~100°C; stable from pH 1.18–8.48 [2] |

Genetic Encoding

The human genome contains four genes that encode ubiquitin: UBA52 and RPS27A, which produce fusion proteins with ribosomal subunits L40 and S27a, respectively; and UBB and UBC, which code for polyubiquitin precursor proteins [1] [2]. This genetic arrangement enables the cell to rapidly generate large quantities of free ubiquitin through proteolytic cleavage of these precursors [1].

The Enzymatic Cascade: E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes

Ubiquitin conjugation to substrate proteins proceeds through a three-step enzymatic cascade requiring ATP, involving ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligase (E3) enzymes [1] [3]. This hierarchical system allows for exquisite specificity and regulation, with humans possessing two E1s, approximately 35 E2s, and an estimated 600-700 E3s [1] [3].

Figure 1: The E1-E2-E3 Enzymatic Cascade. Ubiquitin (Ub) is activated by E1 in an ATP-dependent process, transferred to E2, and finally ligated to a substrate protein by E3.

Step 1: Activation by E1 Enzymes

The ubiquitination cascade initiates with ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin by E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes [1] [3]. This two-step reaction first generates a ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate, followed by transfer of ubiquitin to an active-site cysteine residue within the E1 enzyme, forming a high-energy thioester bond with release of AMP [1]. The human genome encodes two E1 enzymes, UBA1 and UBA6, capable of performing this activation [1].

Step 2: Conjugation by E2 Enzymes

The activated ubiquitin is subsequently transferred from E1 to a cysteine residue in the active site of an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme through a transesterification reaction [1] [3]. This step requires the E2 to bind both the activated ubiquitin and the E1 enzyme simultaneously [1]. Humans possess 35 different E2 enzymes characterized by a highly conserved ubiquitin-conjugating catalytic (UBC) fold [1].

Step 3: Ligation by E3 Enzymes

The final step involves an E3 ubiquitin ligase catalyzing the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a substrate protein [1] [3]. E3s function as substrate recognition modules, interacting with both E2 enzymes and specific target proteins [1] [3]. They are categorized based on their mechanism of action and conserved domains:

- RING-type E3s (Really Interesting New Gene) typically function as scaffolds that facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer from the E2 to the substrate [1] [3]. Multi-subunit RING E3s include complexes such as the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) and the SCF complex (Skp1-Cullin-F-box protein) [1].

- HECT-type E3s (Homologous to the E6-AP Carboxyl Terminus) form an obligate thioester intermediate with ubiquitin on a catalytic cysteine residue before transferring it to the substrate [1] [4] [5]. E6-AP, involved in p53 ubiquitination, operates via this mechanism [4] [5].

This sequential cascade results in an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin (Gly76) and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on the substrate protein, though non-canonical linkages to cysteine, serine, threonine, and the N-terminus also occur [1].

Table 2: Enzymes of the Ubiquitination Cascade

| Enzyme Class | Number in Humans | Core Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | 2 [1] | ATP-dependent ubiquitin activation | Forms thioester with ubiquitin; initial step [1] [3] |

| E2 (Conjugating) | ~35 [1] | Accepts ubiquitin from E1 | UBC fold; determines chain topology [1] |

| E3 (Ligase) | ~600-700 [3] | Substrate recognition & ubiquitin transfer | RING (direct transfer) or HECT (intermediate) types [1] [4] |

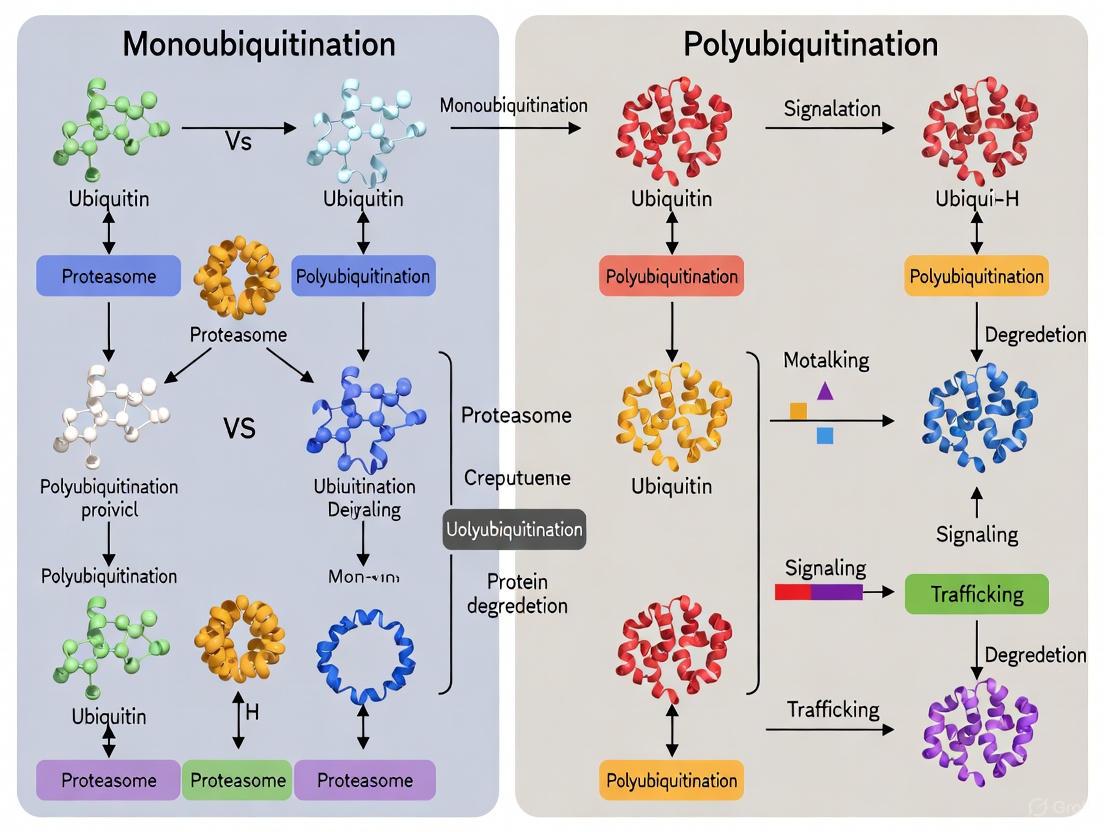

Monoubiquitination vs. Polyubiquitination: Functional Consequences

The ubiquitin code manifests through different modification types, primarily monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination, which trigger distinct functional outcomes for the modified substrate [1] [3] [6]. Understanding this dichotomy is fundamental to appreciating how ubiquitination regulates diverse cellular processes.

Monoubiquitination

Monoubiquitination involves the attachment of a single ubiquitin moiety to a substrate protein [1] [3]. This modification typically serves non-proteolytic functions, including regulation of endocytic trafficking, histone function, DNA repair, virus budding, and nuclear export [1] [3]. Multi-monoubiquitination, where multiple lysine residues on a single substrate each receive one ubiquitin molecule, can also occur and often serves as a signal for internalization of membrane proteins [6].

Polyubiquitination

Polyubiquitination occurs when a chain of ubiquitin molecules is assembled through the linkage of one ubiquitin's C-terminus to a specific lysine residue (or the N-terminal methionine) of the preceding ubiquitin molecule [1] [3]. The specific lysine used for chain linkage determines the three-dimensional structure of the polyubiquitin chain and consequently its functional outcome [1] [3] [7].

Table 3: Polyubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Major Functional Consequences |

|---|---|

| Lys48 (K48) | The canonical "kiss of death"; targets substrates to the 26S proteasome for degradation [1] [3] |

| Lys63 (K63) | Non-degradative signaling; DNA repair, NF-κB activation, endocytosis, kinase activation [1] [3] [7] |

| Met1 (M1) | Linear chains; regulation of inflammatory signaling and NF-κB activation [7] [8] |

| Lys11 (K11) | Cell cycle regulation, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) [7] |

| Lys29 (K29) | Proteasomal degradation, often in collaboration with K48 linkages [7] |

| Lys33 (K33) | Non-degradative; protein kinase regulation, T-cell signaling [7] |

| Lys6 (K6) | DNA damage response, mitophagy [7] |

| Lys27 (K27) | Kinase activation, immune signaling [7] |

Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Beyond homotypic chains, ubiquitin can form heterotypic chains, including branched chains where at least one ubiquitin subunit is modified simultaneously on two different acceptor sites [7]. These complex architectures, such as K11/K48, K29/K48, and K48/K63 branched chains, can be synthesized through collaboration between pairs of E3s with distinct linkage specificities or by individual E3s that recruit multiple E2s [7]. Branched chains may provide enhanced specificity for receptor binding or enable switching between non-proteolytic and degradative signals, as seen during cell signaling and apoptosis [7].

Figure 2: Functional Consequences of Different Ubiquitin Modifications. The type of ubiquitin modification determines the fate and function of the substrate protein.

Reversibility: Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs)

Ubiquitination is a reversible process mediated by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which cleave ubiquitin from substrate proteins [9] [3] [8]. This reversibility allows for dynamic regulation of protein stability, activity, and localization, analogous to phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycles [9]. DUBs perform several critical functions:

- Precursor Processing: Cleave ubiquitin gene products to generate free, mature ubiquitin [9].

- Chain Editing: Trim or completely remove ubiquitin chains from substrates to rescue them from degradation or alter their signaling status [9].

- Ubiquitin Recycling: Cleave ubiquitin from degraded substrates to maintain ubiquitin homeostasis in the cell [9].

Specific DUBs exhibit linkage preference, such as OTULIN, which specifically hydrolyzes Met1-linked linear ubiquitin chains and plays crucial roles in immune signaling and cell fate decisions [8]. The balance between ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating activities ensures precise temporal control over ubiquitin-dependent processes [9].

Experimental Methods and Research Tools

Advancements in methodology have been crucial for deciphering the complexity of the ubiquitin code. Key techniques include mass spectrometry-based proteomics, linkage-specific reagents, and functional screening approaches.

Ubiquitin Remnant Profiling (DiGly Proteomics)

This mass spectrometry-based approach identifies ubiquitination sites proteome-wide by exploiting the fact that trypsin cleavage of ubiquitinated proteins leaves a characteristic di-glycine (Gly-Gly) remnant attached to the modified lysine residue [6]. Antibodies specific for this di-glycine modification enable enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides from complex tryptic digests, allowing identification of ubiquitination sites by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [6]. This methodology has identified tens of thousands of ubiquitination sites, revealing that a significant proportion of ubiquitination targets newly synthesized proteins for quality control rather than regulatory purposes [6].

Linkage-Specific Tools

- Linkage-Specific Antibodies: Antibodies that recognize particular ubiquitin chain linkages (e.g., K48-only, K63-only) enable enrichment and detection of specific chain types [6].

- UBE2S (UbcH10): An E2 enzyme that specifically synthesizes K11-linked chains, used in in vitro ubiquitination assays [7].

- OTULIN: A Met1-linkage-specific DUB used to study linear ubiquitination [8].

Functional Screening Methods

- Global Protein Stability (GPS) Profiling: A high-throughput screening method that uses fluorescent protein reporters to identify substrates of specific E3 ligases by monitoring changes in protein stability upon E3 inhibition or knockdown [3] [6].

- CRISPR-Cas9/Screening: Genetic screens to identify E3 ligase substrates and components of ubiquitin signaling pathways [3].

- MLN4924: A small-molecule inhibitor of the NEDD8-activating enzyme that indirectly inhibits cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), used to identify CRL substrates [6].

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Research Tool | Type | Primary Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| DiGlycine (K-ε-GG) Antibody | Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry [6] |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Antibody Panel | Detection and enrichment of specific ubiquitin chain types [6] |

| MLN4924 (NEDD8-Activating Enzyme Inhibitor) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Investigation of cullin-RING ligase substrates and functions [6] |

| Bortezomib/ MG132 | Proteasome Inhibitors | Determine if ubiquitination leads to proteasomal degradation [3] |

| UBE2S (UbcH10) | Recombinant Enzyme (E2) | In vitro synthesis of K11-linked ubiquitin chains [7] |

| OTULIN | Recombinant Enzyme (DUB) | Selective cleavage of Met1-linear ubiquitin chains [8] |

Pathophysiological and Clinical Significance

Dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling contributes to numerous human diseases, making the ubiquitin-proteasome system an attractive therapeutic target [3] [8].

- Cancer: Mutations in ubiquitin system components are frequent in cancer. For example, von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease results from mutations in the VHL E3 ligase, leading to stabilization of HIF-1α and uncontrolled angiogenesis [3]. Additionally, MDM2-mediated ubiquitination of p53 is a key regulatory mechanism often dysregulated in tumors [3].

- Neurodegenerative Disorders: Impaired ubiquitin-mediated clearance of misfolded proteins contributes to Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases, leading to toxic protein aggregation [8].

- Developmental Disorders: Angelman syndrome results from mutations in the UBE3A E3 ligase gene, while 3-M syndrome stems from mutations in CUL7, a component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [3].

- Immune Disorders: Dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling in immune pathways, particularly those involving NF-κB and Met1-linked ubiquitin chains, can lead to autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases [9] [8].

The clinical relevance of ubiquitination is exemplified by the success of proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib in treating multiple myeloma, validating the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway as a viable drug target [3]. Ongoing research focuses on developing more specific therapeutics targeting individual E3 ligases or DUBs [8].

The ubiquitin system represents a sophisticated regulatory network that controls virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology through diverse signaling mechanisms. The fundamental distinction between monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination, combined with the specificity afforded by different chain linkages and architectures, creates a complex "ubiquitin code" that governs protein fate and function. The reversible nature of this modification, mediated by the opposing actions of E1-E2-E3 enzymes and DUBs, allows for dynamic cellular responses to changing conditions. Continued technological advances in identifying ubiquitination sites and deciphering the functions of specific ubiquitin signals will undoubtedly yield new insights into cellular regulation and provide novel therapeutic avenues for treating human diseases caused by dysregulation of the ubiquitin system.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that controls a vast array of cellular processes, including protein degradation, DNA repair, cell signaling, and endocytosis [10] [11]. The versatility of this modification stems from the structural diversity of ubiquitin itself. A 76-amino acid protein, ubiquitin can be conjugated to substrate proteins as a single moiety or as polymers, creating a complex "code" that is interpreted by the cell to elicit specific functional outcomes [1] [7]. This code is defined by the type of ubiquitin modification—monoubiquitination, multi-monoubiquitination, or polyubiquitination—each generating distinct biological signals [12] [13]. The critical importance of this system is highlighted by the fact that alterations in ubiquitin signaling pathways are found in a broad range of genetic diseases and cancers [13]. This technical guide delineates these ubiquitin modifications, their functional consequences, and the experimental methodologies used to distinguish between them, providing a framework for researchers investigating ubiquitin-dependent processes in health and disease.

Defining the Ubiquitin Modifications

Ubiquitin can be attached to substrate proteins through distinct mechanisms, which determine the functional consequences for the modified protein. The table below provides a structured comparison of the key characteristics of each modification type.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Ubiquitin Modification Types

| Feature | Monoubiquitination | Multi-Monoubiquitination | Polyubiquitination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to one lysine residue on a substrate protein [14] [13]. | Attachment of single ubiquitin molecules to multiple lysine residues on a substrate protein [12] [13]. | Attachment of a chain of ubiquitin molecules to a single lysine residue on a substrate protein [12] [10]. |

| Structural Pattern | One ubiquitin per substrate lysine [14]. | Multiple single ubiquitins on different substrate lysines [12]. | Ubiquitin molecules linked end-to-end via one of seven lysines or the N-terminal methionine [10] [1]. |

| Primary Functional Consequences | Regulates endocytosis, subcellular localization, protein-protein interactions, and DNA repair [15] [13]. | Can signal for proteasomal degradation or lysosomal sorting; amplifies monoubiquitination signals [13] [16]. | Fate depends on chain linkage: e.g., K48 for proteasomal degradation, K63 for signaling, M1 for inflammation [10] [1] [7]. |

The following diagram illustrates the structural relationships between these different modification types.

Structural Classification of Ubiquitin Modifications

Functional Consequences and Biological Significance

The type of ubiquitin modification attached to a substrate protein determines its cellular fate and function, with different topologies being "read" by specific cellular machineries.

Monoubiquitination and Multi-Monoubiquitination

Contrary to early understanding, monoubiquitination does not typically serve as a signal for proteasomal degradation but plays other distinct roles [15]. Its functions are diverse and critical for cellular homeostasis:

- Membrane Trafficking and Endocytosis: Monoubiquitination of cell-surface receptors (e.g., receptor tyrosine kinases) serves as a signal for their internalization via endocytosis and subsequent targeting to lysosomes for degradation by lysosomal proteases [15] [13]. This process is crucial for attenuating signaling from activated receptors.

- Control of Subcellular Localization: The attachment of a single ubiquitin can direct proteins to specific cellular compartments. For example, monoubiquitination targets the TNF receptor associated factor 4 (TRAF4) to cell-cell junctions, which is required for cell migration [13].

- Regulation of Protein-Protein Interactions: Monoubiquitination can either facilitate or inhibit protein interactions. It can create new binding surfaces for proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) or, conversely, cause steric hindrance. For instance, monoubiquitination within the effector-binding domain of the small GTPase RALB sterically inhibits its binding to the downstream effector EXO84 [13].

- Proteasomal Degradation: Although less common, monoubiquitination can target certain proteins for proteasomal degradation, particularly those smaller than 150 amino acids with low structural disorder [13]. Multi-monoubiquitination can also serve as a potent degradation signal, as demonstrated with Cyclin B1, where it promotes proteasomal degradation and mitotic exit [13].

The functional outcome of monoubiquitination can be highly specific, depending on the exact lysine residue modified on the substrate. For example, monoubiquitination of the small GTPase HRAS at K170 impairs its membrane association and downstream signaling, whereas modification at other lysines (K117 or K147) promotes activation [13].

Polyubiquitination

Polyubiquitin chains are specialized for different cellular functions based on the linkage type that connects the ubiquitin monomers. The chain topology determines which effector proteins will bind and what the functional outcome will be [10] [7].

Table 2: Functions of Major Polyubiquitin Chain Linkages

| Linkage Type | Major Known Functions | Cellular Processes |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [10] [1]. | Protein turnover, cell cycle regulation, stress response [10] [16]. |

| K63-linked | Non-degradative signaling; scaffold for complex assembly [10] [13]. | DNA damage response, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis, inflammation [10] [7]. |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation, particularly during mitosis [10] [7]. | Cell cycle regulation, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) [10]. |

| K6-linked | DNA damage response, mitophagy [10] [7]. | DNA repair, mitochondrial quality control. |

| M1-linked (Linear) | Regulation of inflammatory signaling and NF-κB activation [10]. | Immune and inflammatory responses. |

The complexity of the ubiquitin code is further enhanced by the existence of branched ubiquitin chains, where a single ubiquitin monomer is modified simultaneously on at least two different acceptor sites [7]. These chains can integrate multiple signals. For example, branched K48/K63 chains can convert a non-degradative K63-linked signal into a degradative signal by the addition of K48 linkages, providing a mechanism for the precise regulation of signaling pathways [7].

Experimental Protocols for Differentiation

A fundamental challenge in ubiquitin research is experimentally distinguishing between polyubiquitination and multi-monoubiquitination, as both modifications result in the appearance of high-molecular-weight species on SDS-PAGE Western blots [12]. The following established protocol utilizes a mutant form of ubiquitin to differentiate between these modifications.

Protocol: Distinguishing Polyubiquitination from Multi-Monoubiquitination

This protocol is based on performing parallel in vitro ubiquitin conjugation reactions with wild-type ubiquitin and a mutant "Ubiquitin No K" in which all seven lysine residues are mutated to arginines [12].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Assays

| Reagent | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme; initiates the ubiquitination cascade by activating ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner [12] [1]. |

| E2 Enzyme | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; accepts activated ubiquitin from E1 and works with E3 to transfer it to the substrate [12] [1]. |

| E3 Ligase | Ubiquitin ligase; confers substrate specificity by binding both the E2~Ub complex and the target protein [12] [1]. |

| Wild-Type Ubiquitin | The native, unmodified form of ubiquitin capable of forming all chain linkage types [12]. |

| Ubiquitin No K | A mutant form of ubiquitin (all lysines mutated to arginine) that can be conjugated to substrates but cannot form polyubiquitin chains [12]. |

| MgATP Solution | Provides the energy (ATP) and cofactor (Mg²âº) required for the E1-mediated activation of ubiquitin [12]. |

Procedure for 25 µL Reactions:

Reaction Setup:

- Reaction 1 (Wild-Type Ubiquitin): Combine the following in a microcentrifuge tube:

- X µL dH₂O (to bring final volume to 25 µL)

- 2.5 µL 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP)

- 1 µL Wild-Type Ubiquitin (~100 µM final)

- 2.5 µL MgATP Solution (10 mM final)

- X µL Substrate protein (5-10 µM final)

- 0.5 µL E1 Enzyme (100 nM final)

- 1 µL E2 Enzyme (1 µM final)

- X µL E3 Ligase (1 µM final) [12]

- Reaction 2 (Ubiquitin No K): Prepare identically to Reaction 1, but substitute Wild-Type Ubiquitin with 1 µL of Ubiquitin No K mutant [12].

- Negative Control: Replace the MgATP Solution with an equal volume of dHâ‚‚O.

- Reaction 1 (Wild-Type Ubiquitin): Combine the following in a microcentrifuge tube:

Incubation: Incubate both reaction tubes in a 37°C water bath for 30-60 minutes [12].

Reaction Termination:

Analysis:

- Separate the reaction products by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane.

- Perform Western blotting using an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

- Interpret the results as outlined in the diagram below.

Experimental Workflow for Differentiating Ubiquitin Modifications

Implications for Disease and Therapeutics

Understanding the specific roles of different ubiquitin modifications has profound implications for drug development, as alterations in these pathways are linked to numerous diseases [13]. For instance, monoubiquitination regulates the activity and localization of key oncoproteins like RAS, and its dysregulation can contribute to tumorigenesis [13]. Furthermore, mutations in E3 ubiquitin ligases or deubiquitinases (DUBs) that control the balance between different ubiquitin signals are frequently found in cancers and neurological disorders [16]. Targeted therapeutic strategies are emerging, including:

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: Developing compounds that selectively inhibit E3 ligases responsible for the degradative polyubiquitination of tumor suppressor proteins [13].

- DUB Inhibitors: Targeting DUBs that remove degradative ubiquitin signals from oncoproteins, leading to their stabilization [17].

- Linkage-Specific Probes: Using chemical biology tools to dissect the role of specific chain linkages in disease pathways, which can reveal new therapeutic targets [7].

The expanded understanding of branched ubiquitin chains and non-canonical ubiquitination events opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention by targeting highly specific nodes within the ubiquitin signaling network [7].

The ubiquitin system, with its capacity to generate monoubiquitination, multi-monoubiquitination, and polyubiquitination signals, represents a sophisticated regulatory code that controls virtually all aspects of cellular function. The functional consequences of these modifications are distinct—monoubiquitination primarily regulates trafficking and signaling, while the outcomes of polyubiquitination are exquisitely dependent on chain linkage type. The experimental methodologies to decode these signals, such as the use of lysine-less ubiquitin mutants, are critical tools for researchers. As our knowledge of this system deepens, particularly in the realms of branched chains and linkage-specific functions, so too does the potential for developing novel therapeutics that target the ubiquitin machinery in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and immune disorders.

The post-translational modification of proteins by ubiquitin is a fundamental regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells. While the initial discovery of ubiquitination focused on its role in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation via lysine 48 (K48)-linked polyubiquitin chains, research has revealed a far more complex and sophisticated signaling system [18]. The ubiquitin code encompasses diverse modifications, including monoubiquitination, multi-monoubiquitination, and various forms of polyubiquitination [6]. This review frames the topology of polyubiquitin chains within the broader functional consequences of monoubiquitination versus polyubiquitination.

Monoubiquitination, the attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to a substrate, typically alters protein localization, complex formation, or endocytic trafficking [6]. In contrast, polyubiquitination—the formation of chains through covalent linkage between ubiquitin molecules—can generate a vast array of distinct signals. Ubiquitin itself contains seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can serve as linkage points, each potentially conferring unique structural and functional properties [19] [20]. The resulting "ubiquitin code" enables the precise control of protein stability, activity, and interaction networks, rivaling the complexity of phosphorylation [6]. Understanding this code, particularly the signaling capabilities of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chains, is essential for deciphering cellular regulation and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Structural Principles and Functional Consequences of Chain Topology

The topology of a polyubiquitin chain—defined by its linkage type and architecture—directly determines its three-dimensional structure and thus its functional output. This relationship between structure and function forms the basis of the ubiquitin code.

Homotypic, Mixed, and Branched Chains

Polyubiquitin chains exist in several topological forms:

- Homotypic Chains: Composed of a single linkage type (e.g., all K48 linkages or all K63 linkages). These were the first to be characterized and remain the best-understood forms [19].

- Mixed-Linkage Chains: Unbranched chains containing more than one type of Ub-Ub linkage within the same polymer [19].

- Branched Chains: A single ubiquitin molecule serves as a branching point, with two or more ubiquitins attached to different lysine residues on the same proximal ubiquitin molecule (e.g., [Ub]₂–48,63Ub) [19] [21].

Recent studies have revealed that K48 and K63 linkages are the most abundant in cells and can co-exist within the same chain, creating mixed or branched structures with hybrid signaling properties [19] [21].

Linkage-Specific Structural and Functional Properties

Different ubiquitin chain linkages adopt distinct conformations that are recognized by specific receptor proteins, leading to diverse functional outcomes.

Table 1: Functional Consequences of Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types

| Linkage Type | Chain Conformation | Primary Functions | Key Readers/Effectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Compact | Proteasomal degradation [19] [21] | Proteasome, hHR23A [19] |

| K63 | Extended | Signaling, endocytosis, DNA repair, kinase activation [19] [21] [20] | TAB2/3, Rap80 [19] [21] |

| K11 | Mixed | Proteasomal degradation, ER-associated degradation (ERAD) [20] | Proteasome |

| K29/K33 | Not well characterized | Proteasomal degradation, ER retention [20] | Not well characterized |

| M1 (Linear) | Extended | NF-κB signaling, inflammation | NEMO |

| Branched (K48-K63) | Hybrid | Signal amplification, protection from deubiquitinases [21] | TAB2, protects from CYLD [21] |

The functional orthogonality of different linkages is clearly demonstrated by K48 and K63 chains. K48-linked chains typically adopt a compact, closed conformation that serves as the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [19]. In contrast, K63-linked chains generally form more open, extended structures that function in non-proteolytic signaling pathways, including NF-κB activation, DNA damage repair, and endocytic trafficking [19] [18]. This fundamental distinction underscores how chain topology dictates functional output.

Quantitative Landscape of Polyubiquitin Chains

Advances in mass spectrometry-based proteomics have enabled the quantification of different ubiquitin linkage types, providing insights into their relative abundance and dynamics in cells.

Relative Abundance of Different Linkage Types

Global proteomic analyses reveal that K48 and K63 linkages dominate the cellular ubiquitin landscape, though their precise ratios can vary by cell type and condition. A study analyzing polyubiquitination on the KCNQ1 ion channel found that among the di-glycine modified ubiquitin lysine residues, K48 was fractionally dominant (72%) followed by K63 (24%), while atypical chains (K11, K27, K29, K33, and K6) collectively accounted for only 4% [20]. This distribution highlights the predominance of K48 and K63 linkages, though the exact proportions are likely substrate- and context-dependent.

Mass-spectrometry-based quantification has further revealed that K48-K63 branched ubiquitin linkages are abundant in mammalian cells and are dynamically regulated in response to specific stimuli, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) [21]. This discovery established branched chains not as rare artifacts but as functionally significant components of the ubiquitin code.

Functional Classification of Ubiquitination Sites

Comprehensive ubiquitin proteomics datasets have enabled the functional categorization of ubiquitination sites based on their behavior under proteasome inhibition:

Table 2: Classification of Ubiquitination Events by Functional Outcome

| Classification | Response to Proteasome Inhibition | Proposed Function | Example Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome-Dependent | Ubiquitination level increases | Targets substrates for degradation [6] | Misfolded proteins, cell cycle regulators |

| Proteasome-Independent | Ubiquitination level decreases or unchanged | Signaling, localization, activity modulation [6] | Signaling intermediates (e.g., in NF-κB pathway) |

| Quality Control | Highly sensitive to protein synthesis inhibition | Tags misfolded nascent proteins [6] | Newly synthesized proteins |

| Regulatory | Regulated by specific signals | Controlled modulation of pathway activity [6] | Activated receptors, transcription factors |

Strikingly, a significant finding from quantitative ubiquitinomics is that the majority of ubiquitination in cells occurs on newly synthesized proteins, likely representing a quality control mechanism to eliminate misfolded polypeptides [6]. This highlights the importance of distinguishing these "housekeeping" ubiquitination events from regulatory ones when interpreting ubiquitination data.

Experimental Methodologies for Deciphering the Ubiquitin Code

Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitinomics

Ubiquitin Remnant Profiling is a powerful mass spectrometry-based approach for system-wide identification of ubiquitination sites [6].

Protocol Overview:

- Cell Lysis: Prepare protein extracts under denaturing conditions to preserve ubiquitination and inhibit deubiquitinases.

- Trypsin Digestion: Digest proteins with trypsin. Ubiquitin's C-terminal -Arg-Gly-Gly leaves a di-glycine (Gly-Gly) remnant on the modified lysine after tryptic cleavage.

- Immunoaffinity Enrichment: Use antibodies specific for the di-glycine lysine modification to enrich for ubiquitinated peptides.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze enriched peptides by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry.

- Data Analysis: Identify ubiquitination sites by searching mass spectra for the di-glycine modification (114.0429 Da mass shift) on lysine residues.

This approach can be adapted to profile linkage-specific ubiquitination by pre-enriching for specific chain types using linkage-specific antibodies prior to digestion [6].

Engineered Deubiquitinases (enDUBs) for Linkage-Specific Editing

A recent breakthrough methodology involves the development of linkage-selective engineered deubiquitinases (enDUBs) to selectively remove specific polyubiquitin linkages from target proteins in live cells [20].

Protocol Overview:

- enDUB Design: Fuse the catalytic domains of deubiquitinases (DUBs) with specific linkage preferences to a GFP-targeted nanobody.

Validation: Test the enDUB's ability to decrease basal ubiquitination of the target protein (e.g., KCNQ1-YFP) by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies [20].

Functional Assays: Assess the functional consequences of removing specific linkages on substrate:

- Surface Expression: For membrane proteins, use flow cytometry with extracellular tagging (e.g., bungarotoxin binding site) [20].

- Subcellular Localization: Use confocal microscopy with compartment-specific markers (ER, Golgi, endosomes) [20].

- Protein Stability: Measure half-life changes via cycloheximide chase assays.

- Functional Activity: For enzymes or channels, assess catalytic activity or ion currents.

This approach revealed that distinct linkages control different aspects of KCNQ1 regulation: K48 is necessary for forward trafficking, while K63 enhances endocytosis and reduces recycling [20].

Structural and Biophysical Analysis of Mixed Linkage Chains

NMR spectroscopy has been instrumental in demonstrating that mixed linkage chains retain the structural features of their homogeneous counterparts.

Protocol Overview:

- Chain Synthesis: Generate defined ubiquitin chains (e.g., Ub–63Ub–48Ub, Ub–48Ub–63Ub, and branched [Ub]₂–48,63Ub) using enzymatic or chemical methods [19].

- Isotopic Labeling: Incorporate ¹âµN-specific labels into specific Ub units within the chain (e.g., Ub[Ub(¹âµN)]–48,63Ub) [19].

- NMR Spectroscopy: Collect ¹âµN-¹H HSQC spectra to probe the chemical environment and dynamics of each Ub unit in the chain.

- Chemical Shift Analysis: Compare chemical shifts to those of homogeneous chains to determine if linkage-specific interdomain contacts are preserved [19].

This methodology confirmed that K48 and K63 linkages in mixed chains are virtually indistinguishable from their counterparts in homogeneously-linked polyUb, retaining their distinctive structural properties even when present in the same polymer [19].

K48-K63 Branched Chain in NF-κB Signaling

Case Study: K48-K63 Branched Chains in NF-κB Signaling

The functional significance of branched ubiquitin chains is exemplified by their role in regulating NF-κB signaling, a critical pathway in inflammation and immunity.

Pathway Mechanism and Experimental Validation

In response to IL-1β stimulation, the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 first assembles K63-linked polyubiquitin chains, which serve as a platform for signaling complex assembly [21]. Subsequently, the E3 ligase HUWE1 generates K48 branches on these K63 chains, forming K48-K63 branched ubiquitin linkages [21]. This branched architecture creates a unique regulatory signal with two key functional consequences:

- Recognition by TAB2: The branched chain maintains recognition by TAB2, a component of the TAK1 kinase complex that activates NF-κB signaling [21].

- Protection from Deubiquitinases: The K48 branch protects the K63 linkages from cleavage by the deubiquitinase CYLD, thereby prolonging the NF-κB signal [21].

This cooperative mechanism between K48 and K63 linkages demonstrates how ubiquitin chain branching can generate complex regulatory logic that differentially controls the readout of the ubiquitin code by specific "reader" and "eraser" proteins.

Experimental Evidence

The critical role of branched chains was established through multiple experimental approaches:

- Quantitative Mass Spectrometry: Revealed abundant K48-K63 branched linkages in mammalian cells that increase in response to IL-1β [21].

- Genetic Manipulation: Knockdown of HUWE1 impaired K48-K63 branch formation and attenuated NF-κB activation [21].

- Biochemical Assays: Reconstituted systems demonstrated that HUWE1 directly adds K48 branches to K63 chains assembled by TRAF6 [21].

- Deubiquitinase Protection Assays: CYLD efficiently cleaved homogeneous K63 chains but was significantly impaired against K48-K63 branched chains [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Polyubiquitin Chains

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Features / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Detect and enrich specific polyubiquitin chain types [19] [6] | Commercial antibodies for K48, K63, K11, M1 linkages |

| Activity-Based DUB Probes | Profile deubiquitinase activity and specificity [20] | Ubiquitin-based probes with fluorescent or affinity tags |

| Engineered DUBs (enDUBs) | Linkage-selective editing of target protein ubiquitination in live cells [20] | OTUD1 (K63-selective), OTUD4 (K48-selective), Cezanne (K11-selective) |

| Di-Glycine (K-ε-GG) Antibody | System-wide identification of ubiquitination sites by mass spectrometry [6] | Enriches tryptic peptides with di-glycine remnant on modified lysines |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | Dissect linkage-specific functions [19] | Lysine-to-arginine (K-to-R) mutants (e.g., K48R, K63R) |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Distinguish proteasomal vs. non-proteasomal ubiquitin functions [20] [6] | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib |

| DUB Inhibitors | Investigate ubiquitination dynamics [21] | PR-619 (broad-spectrum), specific inhibitors for USP7, USP14 |

| Defined Ubiquitin Chains | Structural studies and in vitro reconstitution assays [19] | Homogeneous chains (K48, K63), mixed/branched chains (K48-K63) |

| Cox-2-IN-35 | COX-2-IN-35|Selective COX-2 Inhibitor|RUO | COX-2-IN-35 is a potent, selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor for research use only. It is not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| PROTAC tubulin-Degrader-1 | PROTAC tubulin-Degrader-1, MF:C35H35N3O10, MW:657.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The topology of polyubiquitin chains—from homotypic linear chains to complex mixed and branched structures—generates an exquisite coding system that regulates virtually all cellular processes. The functional consequences of polyubiquitination are far more diverse than simply targeting proteins for degradation, encompassing precise control of protein localization, activity, and interactions. The distinction between monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination represents just one layer of this complex regulatory system, with different chain topologies adding further sophistication.

Recent methodological advances, including ubiquitin remnant profiling, engineered deubiquitinases, and sophisticated biophysical approaches, are rapidly accelerating our ability to decipher this code. The discovery that K48-K63 branched chains function as regulated signaling amplifiers in the NF-κB pathway demonstrates that ubiquitin chain branching is not a biochemical curiosity but a functionally significant feature of cellular regulation [21]. Furthermore, the development of linkage-selective enDUBs provides a powerful new tool for establishing causal relationships between specific ubiquitin linkages and functional outcomes in live cells [20].

As our understanding of the ubiquitin code deepens, new therapeutic opportunities are emerging. The recent construction of a pancancer ubiquitination regulatory network that stratifies patients by risk and predicts immunotherapy response highlights the clinical potential of targeting ubiquitination pathways [22]. By understanding how specific chain topologies control protein fate and function, we can begin to develop strategies to manipulate the ubiquitin code for therapeutic benefit, potentially targeting traditionally "undruggable" pathways in cancer, neurodegeneration, and inflammatory diseases.

Ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, serves as a fundamental regulatory mechanism that governs virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes. This post-translational modification exhibits remarkable functional diversity, primarily dictated by the topology of ubiquitin conjugation. The dichotomy between proteasomal degradation and non-degradative signaling fates represents a central paradigm in ubiquitin biology [23] [6]. When ubiquitin molecules form polyubiquitin chains linked through specific lysine residues (notably Lys48), they typically target substrates for destruction by the 26S proteasome [24] [23]. In contrast, monoubiquitination (single ubiquitin attachment) and certain atypical polyubiquitin chains (such as Lys63-linked) function as non-degradative signals that regulate processes including protein trafficking, DNA repair, kinase activation, and inflammatory signaling [24] [25] [23].

The specificity of ubiquitin signaling is encoded through a complex enzymatic cascade involving ubiquitin-activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligase (E3) enzymes, with over 500 E3 ligases providing substrate specificity in humans [23] [6]. This regulatory system is dynamically reversible through the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which remove ubiquitin modifications, enabling precise spatiotemporal control of protein function [23] [26]. Understanding the molecular determinants that direct substrates toward degradative versus non-degradative fates is essential for deciphering cellular regulatory mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

The Ubiquitin Conjugation Machinery

The ubiquitination pathway employs a hierarchical enzymatic cascade that confers specificity and regulatory potential at multiple levels [26]:

- E1 Ubiquitin-Activating Enzymes: Initiate the pathway through ATP-dependent formation of a thioester bond with ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine

- E2 Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes: Receive activated ubiquitin from E1 via trans-thioesterification

- E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Catalyze the final transfer of ubiquitin to substrate lysine residues, determining substrate specificity

The human genome encodes approximately 500 E3 ligases, rivaling the complexity of the kinase system [6]. This extensive repertoire enables precise targeting of countless substrates under diverse physiological conditions. Additionally, the process is counterbalanced by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which remove ubiquitin modifications, making ubiquitination a dynamically reversible process [23] [26].

Table 1: Core Enzymatic Components of the Ubiquitin System

| Component | Number in Humans | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzymes | ~2 | Ubiquitin activation | ATP-dependent, forms E1~Ub thioester |

| E2 Enzymes | ~40 | Ubiquitin conjugation | Determines chain topology, E2~Ub thioester |

| E3 Ligases | ~500 | Substrate recognition | Provides substrate specificity, largest family |

| DUBs | ~90 | Deubiquitination | Reverses modification, recycles ubiquitin |

The coordination between these enzymatic components determines whether a substrate undergoes monoubiquitination, multiple monoubiquitination, or polyubiquitination with specific chain linkages, ultimately dictating the functional outcome of the modification [27] [12].

Determinants of Functional Outcomes

Ubiquitin Chain Topology and Linkage Specificity

The functional consequence of ubiquitination is primarily determined by the type of ubiquitin modification and the specific lysine residue used for chain formation within ubiquitin itself. Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1), all capable of forming polyubiquitin chains with distinct structural and functional properties [26].

Proteasome-Targeting Signals: K48-linked polyubiquitin chains represent the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [24] [23]. Recent research using the UbiREAD technology revealed that K48-linked chains must consist of at least three ubiquitin molecules to efficiently target substrates for degradation, with half-lives of approximately one minute for substrates modified with these chains [28]. Shorter K48 chains (di-ubiquitin) are rapidly disassembled by DUBs, maintaining substrate stability [28]. Other linkage types including K6, K11, K27, K29, and M1 have also been implicated in proteasomal targeting, demonstrating greater complexity than previously recognized [26].

Non-Degradative Signals: K63-linked polyubiquitin chains serve as the prototype non-degradative ubiquitin signal, functioning in DNA repair, endocytosis, kinase activation, and inflammatory signaling [25]. These chains are rapidly deubiquitinated and do not significantly affect substrate stability [28]. Monoubiquitination and multiple monoubiquitination (attachment of single ubiquitins to multiple lysines) also function as non-degradative signals that can alter subcellular localization, protein-protein interactions, and activity [12] [23].

Table 2: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Functional Consequences

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Cellular Processes | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Proteasomal degradation | Cell cycle, protein quality control | Compact structure, proteasome recognition |

| K63 | Non-degradative signaling | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis | Extended structure, protein interactions |

| K11 | Proteasomal degradation | ER-associated degradation, cell cycle | Mixed compact/extended conformations |

| M1 (linear) | Inflammatory signaling | NF-κB activation, immunity | Extended structure, recognized by LUBAC |

| K27, K29 | Proteasomal & lysosomal degradation | Protein quality control, innate immunity | Less characterized, diverse functions |

| K6, K33 | Non-degradative functions | DNA damage response, trafficking | Specialized contexts |

Molecular Determinants of Lysine Selection

The mechanisms governing which specific lysine residues are modified on substrates and within ubiquitin chains involve complex molecular recognition events. The "positioning model" suggests that E3 ligases position specific substrate lysines toward the E2~Ub thioester bond to select particular lysines during ubiquitination [24]. However, studies of the SCFCdc4/Cdc34 system in yeast revealed that amino acids surrounding acceptor lysines play critical roles in determining ubiquitination efficiency [24].

Key findings demonstrate that:

- Residues surrounding Sic1 lysines or lysine 48 in ubiquitin are critical for ubiquitination

- This sequence-dependence is linked to evolutionarily conserved key residues in the catalytic region of E2 enzymes

- Single point mutations in the E2 catalytic core can convert polyubiquitinating enzymes into monoubiquitinating enzymes

- The compatibility between determinants in the E2 catalytic region and those surrounding acceptor lysines directs the mode of ubiquitination [24]

These mechanistic insights explain how specific E2/E3 combinations can determine whether a substrate undergoes monoubiquitination versus polyubiquitination, and which lysine linkages are formed in polyubiquitin chains.

Analytical Approaches and Methodologies

Distinguishing Polyubiquitination from Multi-Mono-Ubiquitination

Differentiating between these two ubiquitination modes is essential for understanding functional consequences, as they lead to different substrate fates. A well-established protocol utilizes ubiquitin mutants to distinguish these mechanisms [12]:

Experimental Principle: Two parallel in vitro ubiquitination reactions are performed: one with wild-type ubiquitin and another with "Ubiquitin No K" - a mutant where all seven lysine residues are mutated to arginines. Wild-type ubiquitin supports both polyubiquitin chain formation and multiple monoubiquitination, while Ubiquitin No K can only support multiple monoubiquitination due to its inability to form chains [12].

Interpretation of Results:

- If high molecular weight species appear with wild-type ubiquitin but not with Ubiquitin No K → Polyubiquitination

- If high molecular weight species appear with both wild-type and Ubiquitin No K → Multiple Monoubiquitination

- If both patterns are observed → Mixed ubiquitinationæ¨¡å¼ [12]

This methodology provides a straightforward approach to determine the nature of ubiquitin modifications on specific substrates of interest.

Proteomic Profiling of Ubiquitination Sites

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has revolutionized the large-scale identification of ubiquitination sites. The diGLY-modified peptide enrichment (diGPE) approach, also known as ubiquitin remnant profiling, uses antibodies specific for the diglycine remnant left on modified lysines after tryptic digestion [27] [6].

Key methodological aspects:

- Enrichment Strategy: Antibodies recognizing the diGLY modification enable purification of ubiquitinated peptides from complex tryptic digests

- Quantitative Capabilities: When coupled with SILAC (stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture), diGPE allows quantitative monitoring of site-specific ubiquitylation changes under different biological conditions [27]

- Technical Considerations: Proteasome inhibitors are often utilized to improve detection of labile substrates, while DUB inhibitors can augment protein ubiquitylation levels [27]

This approach has enabled the identification of over 19,000 ubiquitination sites in human cells, revealing that a significant portion of ubiquitination targets newly synthesized proteins for quality control rather than regulatory purposes [6].

Chain Linkage-Specific Analysis

Advanced methodologies have been developed to characterize specific ubiquitin chain linkages:

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs): Engineered, high-affinity reagents composed of multiple ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains that bind polyubiquitin chains with nanomolar affinity [25]. TUBEs with linkage specificity (e.g., for K48 or K63 chains) can be employed in high-throughput assays to study chain-specific ubiquitination events [25].

Linkage-Specific Antibodies: Antibodies recognizing specific ubiquitin linkages enable immunoenrichment of linkage-specific substrates, though challenges remain due to potential cross-reactivity and the existence of mixed chain types on substrates [27].

UbiREAD Technology: A recently developed system that enables systematic survey of degradation capacities of diverse ubiquitin chains, demonstrating that K48-linked chains require at least three ubiquitin molecules to efficiently target substrates for degradation [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Technology | Primary Function | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin No K | Lysine-less ubiquitin mutant | Distinguishing poly- vs multi-mono-ubiquitination | All 7 lysines mutated to arginine; cannot form chains |

| diGLY Antibodies | Immunoaffinity enrichment | Ubiquitin remnant profiling (diGPE) | May exhibit sequence bias; cross-linking improves yield |

| Linkage-Specific TUBEs | Affinity enrichment of specific chains | Studying K48, K63-specific ubiquitination | High nanomolar affinity, 96-well plate formats available |

| MLN4924 | Cullin-RING ligase inhibitor | Identifying CRL substrates | Affects ~200 cullin-dependent E3s; reveals CRL targets |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Block proteasomal degradation | Stabilizing labile ubiquitinated substrates | MG132, bortezomib increase detection sensitivity |

| DUB Inhibitors | Broad DUB inhibition | Augmenting ubiquitination levels | Contrast with RNAi knockdown effects; acute vs chronic effects |

| UbiREAD System | Decoding degradation capacity | Systematic analysis of chain function | Tests homotypic and branched chain functionality |

Biological Case Studies

Proteasomal Regulation of Transcription Factors

The Drosophila transcription factor Longitudinals lacking (Lola) exemplifies how partial proteasomal degradation can generate functionally distinct protein isoforms with opposing biological activities. Research demonstrated that the male-biased Lola29M isoform undergoes proteasome-dependent cleavage to produce the female-specific Lola29F isoform, which counteracts Lola29M function [29]. Surprisingly, the male-specific transcription factor Fruitless (FruBM) protects Lola29M from this cleavage by binding directly to it, thereby preventing production of the feminizing Lola29F isoform [29]. This mechanism represents a sophisticated example of how proteasomal processing, rather than complete degradation, can regulate cell fate decisions in neuronal circuit development.

Ubiquitin Linkages in Innate Immunity

Macrophage polarization provides a compelling example of how different ubiquitin linkages coordinate cellular responses. The NF-κB pathway is regulated by multiple ubiquitin-dependent mechanisms:

- K63-linked and linear (M1-linked) chains promote NF-κB activation by creating platforms for kinase assembly

- K48-linked chains terminate signaling by targeting activated pathway components for degradation [30]

Specific regulators include:

- A20: An ubiquitin-editing enzyme that first removes K63 chains then adds K48 chains to substrates like RIP1 and TRAF6, effectively terminating NF-κB signaling [30]

- OTULIN: Specifically hydrolyzes linear M1-linked ubiquitin chains generated by LUBAC, with loss-of-function causing severe autoinflammatory disease [30]

- TRIM23: Catalyzes atypical K27-linked chains on NEMO to promote IRF3 and NF-κB activation during viral infection [30]

These examples illustrate how the interplay between different ubiquitin linkages creates precise signaling systems that balance activation and termination of immune responses.

Visualization of Ubiquitination Pathways and Methodologies

The Ubiquitin Signaling Cascade

Experimental Workflow for Distinguishing Ubiquitination Types

The functional dichotomy between proteasomal degradation and non-degradative signaling represents a fundamental organizing principle in ubiquitin biology. The specific outcome of ubiquitination is determined by complex interplay between the enzymatic machinery (E2/E3 combinations), the structural features of substrate proteins, and the topology of ubiquitin chains themselves. Analytical methodologies continue to evolve, enabling researchers to precisely distinguish between ubiquitination types and their functional consequences.

Understanding these mechanisms has profound implications for therapeutic development, as evidenced by the growing number of agents targeting specific components of the ubiquitin system. The integration of structural insights, proteomic approaches, and functional assays will continue to unravel the complexity of ubiquitin signaling and its roles in health and disease.

Ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to target proteins, is a paramount post-translational modification that orchestrates a vast array of cellular processes in eukaryotes [3] [8]. The functional consequences of this modification are critically determined by its topology: monoubiquitination (attachment of a single ubiquitin) and polyubiquitination (formation of ubiquitin chains) initiate distinct downstream signaling events [31] [6]. This modification is enacted by a sequential enzymatic cascade involving ubiquitin-activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligating (E3) enzymes, and is reversibly removed by deubiquitinases (DUBs) [3] [8]. The specificity of the system resides in the hundreds of E3 ligases that recognize particular substrates, while the diversity of ubiquitin chain linkages—eight homotypic chains and numerous heterotypic and branched chains—comprises a complex "ubiquitin code" that is interpreted by specialized effector proteins [8] [7] [32]. This whitepaper delineates the governance of key cellular processes by the ubiquitin system, with a focused examination of the divergent biological outcomes triggered by monoubiquitination versus polyubiquitination, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to target this system therapeutically.

Monoubiquitination vs. Polyubiquitination: A Functional Dicharchy

The structural form of the ubiquitin modification is the primary determinant of its functional consequence. The table below systematically compares the core characteristics and functions of monoubiquitination and the major types of polyubiquitin chains.

Table 1: Functional Consequences of Monoubiquitination vs. Polyubiquitination

| Modification Type | Key Linkages | Primary Functions | Representative Processes | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoubiquitination | Single ubiquitin attached to a substrate lysine | Protein trafficking, endocytosis, histone regulation, signal transduction, DNA repair [3] [33] [34]. | Endocytosis of membrane receptors [3], histone H2B ubiquitination in transcription [35] [34], virus budding [3]. | Alters protein activity, interaction network, or subcellular localization without degradation [6]. |

| Lys48-linked Polyubiquitination | Ubiquitin chains linked via Lys48 | Proteasomal degradation [3] [8] [31]. | Degradation of cell cycle regulators, misfolded proteins, and transcription factors like HIF-1α [3]. | Target protein destruction and recycling of amino acids. |

| Lys63-linked Polyubiquitination | Ubiquitin chains linked via Lys63 | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis, kinase activation [3] [8] [31]. | Activation of IKK complex in NF-κB signaling [31], endocytic trafficking [3]. | Serves as a scaffold for assembly of signaling complexes; non-proteolytic. |

| Met1-linked / Linear Polyubiquitination | Chains linked via N-terminal methionine | Inflammatory signaling and NF-κB activation [8]. | TNFR1 and other innate immune signaling pathways [8]. | Assembly of protein complexes for inflammatory response. |

| Branched Polyubiquitination | Two different linkages on same ubiquitin molecule (e.g., K48/K63) | Can enhance proteasomal targeting or create unique signaling platforms [7] [31]. | Apoptosis regulation (e.g., TXNIP degradation), cell cycle control [7] [31]. | Can convert a non-degradative signal (K63) into a degradative one [7]. |

Governing Key Cellular Processes

Programmed Cell Death: Apoptosis and Necroptosis

Ubiquitination is a master regulator of cell death pathways, exerting precise control over both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways, as well as the pro-inflammatory necroptotic pathway [31].

- Intrinsic Apoptosis: This pathway is primarily regulated by the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, a balance often maintained through Lys48-linked polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation [31]. For instance, the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1 and the pro-apoptotic protein Bim are both targeted for ubiquitin-mediated degradation by specific E3 ligases like CRL2CIS and SCFβ-TrCP, respectively. This allows the cell to fine-tune its apoptotic sensitivity in response to internal stresses [31].

- Extrinsic Apoptosis & Necroptosis: The extrinsic pathway, initiated by death receptors, is heavily regulated by non-degradative ubiquitination (e.g., Lys63-linked chains) on core components like FADD and Caspase-8, which typically inhibits their pro-apoptotic activity [31]. When caspase activity is blocked, death receptors can trigger necroptosis. The central necroptosis regulators RIPK1 and RIPK3 are extensively ubiquitinated. The type of ubiquitin modification on RIPK1—governed by different E3 ligases and DUBs—can either promote or inhibit the necroptotic signal, demonstrating a complex regulatory layer that determines cellular fate between survival, apoptotic death, and necroptotic death [31].

DNA Repair and Genome Integrity

Ubiquitin-dependent signaling is critical for the cellular response to DNA damage, facilitating the recruitment of repair machinery and coordinating the DNA damage checkpoint. Lys63-linked and Met1-linked polyubiquitin chains are prominently involved in these pathways, acting as scaffolds to assemble repair complexes at sites of DNA lesions [8]. For example, the RNF8/RNF168 E3 ligase cascade establishes Lys63-linked and heterotypic ubiquitin chains on histones surrounding a DNA double-strand break, which are recognized by effector proteins such as BRCA1 and 53BP1 to initiate homologous recombination or non-homologous end-joining repair, respectively [34].

Endocytosis and Protein Trafficking

Monoubiquitination serves as a key signal for the internalization of cell surface proteins and their sorting into the endolysosomal system [3] [6]. A well-established function is the monoubiquitination of activated receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., EGFR), which acts as a signal for their endocytosis and subsequent trafficking to lysosomes for degradation, thereby terminating signaling [3]. Furthermore, the regulation of ion channel surface density, as exemplified by KCNQ1, is controlled by a complex "ubiquitin code" where distinct chain types direct the channel to different fates: K63-linked chains promote endocytosis and reduce recycling, while K48-linked chains are necessary for forward trafficking [32].

Immune Response and Inflammation

The ubiquitin system is a cornerstone of innate and adaptive immunity [8] [36]. The activation of the transcription factor NF-κB, a central mediator of inflammatory and immune responses, is triggered by Lys63-linked and Met1-linked polyubiquitin chains. Upon TNF receptor engagement, E3 ligases like cIAPs and LUBAC build these chains on RIPK2 and other signaling molecules. These chains serve as platforms to recruit and activate the TAK1 and IKK kinase complexes, leading to the phosphorylation and Lys48-linked polyubiquitination of the NF-κB inhibitor IκBα, targeting it for proteasomal degradation and thereby releasing NF-κB to the nucleus to transcribe target genes [3] [8] [31].

In T-cell development, ubiquitination regulates processes from thymic selection to the establishment of self-tolerance [36]. For instance, the DUB BAP1 is essential for thymocyte development, as its deubiquitinating activity is required for the transition from double-negative (DN) to double-positive (DP) thymocytes, partly by facilitating deubiquitination of histone H2A and allowing proper cell cycle progression [36].

Epigenetic Regulation and Transcription

Histone monoubiquitination is a crucial epigenetic mark that directly modulates chromatin structure and gene expression. H2B monoubiquitination (H2Bub) is generally associated with transcriptional activation. It facilitates nucleosome dynamics and RNA Polymerase II progression during transcription [33] [35] [34]. Recent research has shown that increasing H2Bub in the aged hippocampus by upregulating its E3 ligase, Rnf20, can improve memory and rescue a more youth-like transcriptome, highlighting its role in age-related cognitive decline [35]. In contrast, H2A monoubiquitination (H2Aub) is primarily a repressive mark, often deposited by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1) to silence developmental genes and maintain cell identity [34].

Key Experimental Methodologies and Tools

Deciphering the ubiquitin code requires sophisticated methods to identify substrates, quantify dynamics, and manipulate specific ubiquitination events.

Ubiquitin Remnant Profiling (DiGly Proteomics)

This mass spectrometry-based technique is the gold standard for proteome-wide identification of ubiquitination sites [6]. The method involves tryptic digestion of protein samples, which cleaves ubiquitin but leaves a di-glycine (Gly-Gly) remnant attached to the modified lysine on the substrate peptide. Antibodies specific for this Gly-Gly remnant are used to enrich ubiquitinated peptides, which are then identified and quantified by LC-MS/MS. This approach has revealed that tens of thousands of ubiquitination sites exist in the human proteome, many of which are regulated in response to cellular signals or proteasome inhibition [6].

Linkage-Selective Engineered Deubiquitinases (enDUBs)

To investigate the function of specific polyubiquitin linkages on a protein of interest in live cells, researchers have developed engineered DUBs. These are fusion proteins comprising a substrate-targeting domain (e.g., a GFP-nanobody) and the catalytic domain of a linkage-selective DUB (e.g., OTUD1 for K63, OTUD4 for K48) [32]. When expressed in cells, the enDUB is recruited to the target protein and hydrolyzes the specific polyubiquitin chain type it recognizes. Applying this tool to the KCNQ1 ion channel revealed distinct roles for K11, K48, and K63 chains in regulating its ER retention, forward trafficking, and endocytosis, respectively [32].

Global Protein Stability (GPS) Profiling

This high-throughput screening strategy identifies substrates of specific E3 ligases. It utilizes a library of reporters, each consisting of a protein of interest fused to a fluorescent protein. By monitoring the fluorescence intensity—a proxy for protein stability—before and after inhibition of a specific E3 ligase (e.g., using MLN4924 for cullin-RING ligases), researchers can identify proteins whose stability is controlled by that ligase [3] [6].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function / Mechanism | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| MLN4924 (Nedd8-Activating Enzyme Inhibitor) | Inhibits cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) by blocking cullin neddylation, a crucial activation step. | Identifying CRL substrates via GPS profiling or ubiquitin remnant profiling [6]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib, MG132) | Block the 26S proteasome, preventing degradation of proteins tagged with K48-linked chains. | Stabilizing polyubiquitinated proteins to study degradation substrates; causes accumulation of K48 chains [3] [32]. |

| Linkage-Selective Ubiquitin Antibodies | Antibodies that specifically recognize a particular ubiquitin chain linkage (e.g., K48-only, K63-only). | Immunoblotting or immunofluorescence to detect specific chain types; immunoprecipitation to enrich for proteins modified with specific chains [6]. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 Systems | A catalytically "dead" Cas9 fused to transcriptional activators (e.g., VPR) can be targeted to gene promoters to upregulate expression. | Used to upregulate the H2B ubiquitin ligase Rnf20 in the aged hippocampus to study its role in memory [35]. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Engineered protein domains with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains, which can shield them from DUBs. | Isolating and preserving the native ubiquitinated proteome from cell lysates for downstream analysis. |

Pathway and Experimental Workflow Visualizations

The Ubiquitin Enzymatic Cascade

This diagram illustrates the three-step enzymatic cascade responsible for ubiquitin conjugation, highlighting the roles of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes in activating and transferring ubiquitin to a substrate protein.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Chain Topology

This diagram summarizes the diverse architectures of ubiquitin modifications, from monoubiquitination to homotypic and complex heterotypic chains, and their primary cellular functions.

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Remnant Profiling

This flowchart outlines the key steps in the ubiquitin remnant profiling (DiGly proteomics) methodology for the system-wide identification of ubiquitination sites.

The ubiquitin system is a master regulatory network that governs cellular fate and function through the precise and reversible modification of proteins. The fundamental dichotomy between monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination, and the exquisite specificity encoded within the diverse polyubiquitin chain architectures, allows this system to control processes as varied as protein degradation, signal transduction, epigenetic regulation, and immune response. For drug development professionals, the enzymes of the ubiquitin system—particularly the ~600 E3 ligases and ~100 DUBs—represent a vast and promising landscape of therapeutic targets [8] [36]. The clinical success of proteasome inhibitors in oncology validates the therapeutic potential of modulating this pathway. Future efforts are focused on developing small molecules that target specific E3 ligases or DUBs, as well as leveraging proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) to hijack the ubiquitin system for the degradation of disease-causing proteins. As tools like ubiquitin remnant profiling and engineered enDUBs continue to decode the complexities of the ubiquitin code, our ability to design precise, effective, and novel therapeutics for cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and immune disorders will be fundamentally enhanced.

Advanced Techniques for Discriminating and Applying Ubiquitin Signals

This technical guide outlines the experimental framework for employing in vitro ubiquitination assays with wild-type (WT) and lysine-null (K0) ubiquitin to dissect the functional consequences of monoubiquitination versus polyubiquitination. Protein ubiquitination, a paramount post-translational modification, regulates a vast array of cellular processes, with the outcome heavily dependent on the type of ubiquitin modification installed. The ubiquitination cascade is mediated by the sequential action of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [37] [38]. While polyubiquitin chains, linked via specific lysine residues (e.g., K48, K63), often signal for proteasomal degradation or non-proteolytic functions, monoubiquitination exerts distinct effects on protein activity, localization, and interactions [24] [39]. The use of K0 ubiquitin, in which all seven lysine residues are mutated, is a powerful tool to restrict the enzymatic output to monoubiquitination or the formation of atypical chains on non-lysine residues, thereby enabling the precise study of monoubiquitination's functional role. This document provides detailed methodologies, expected outcomes, and practical considerations for integrating these assays into a research thesis focused on ubiquitin signaling.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a crucial mechanism for controlled protein degradation and signaling in eukaryotic cells. Ubiquitin is a 76-amino-acid protein that is covalently attached to substrate proteins via a three-enzyme cascade [38]. The process initiates with ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin by an E1 enzyme, forming a thioester bond with the E1's active-site cysteine. Ubiquitin is then transferred to the catalytic cysteine of an E2 conjugating enzyme. Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a substrate protein, typically forming an isopeptide bond with the ε-amino group of a lysine residue [37] [24].

A critical feature of ubiquitin signaling is the ability to form polyubiquitin chains. Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63), each of which can serve as an attachment point for another ubiquitin molecule, leading to chain formation. The topology of the chain—defined by the lysine used for linkage—creates a specific code that determines the fate of the modified protein. For instance, K48-linked chains primarily target substrates for degradation by the 26S proteasome, whereas K63-linked chains are involved in non-degradative processes like DNA repair, kinase activation, and endocytosis [37] [24] [39]. In contrast, monoubiquitination, the attachment of a single ubiquitin moiety, regulates processes such as histone function in transcription, endocytic trafficking, and DNA repair [39].

The lysine-null (K0) ubiquitin mutant is an indispensable tool for ubiquitin research. By mutating all seven lysine residues to arginine (or other non-ubiquitinatable residues), this mutant cannot form conventional lysine-linked polyubiquitin chains. In vitro assays employing K0 ubiquitin allow researchers to:

- Isolate the effects of monoubiquitination from those of polyubiquitination.

- Study the formation and function of non-lysine ubiquitination on serine, threonine, or cysteine residues, which has emerged as a significant regulatory mechanism [37].

- Identify E2/E3 combinations that are specialized for monoubiquitination or specific chain types.

This guide is designed to facilitate the study of these distinct ubiquitin signals within a broader thesis on their functional consequences.

Experimental Design and Workflow

A well-structured in vitro ubiquitination assay requires careful planning and optimization. The workflow below outlines the key stages, from reagent preparation to data analysis.

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a complete experimental series using WT and K0 ubiquitin.

Core Ubiquitination Reaction Mechanism

Understanding the enzymatic cascade is fundamental to designing the assay. The mechanism of ubiquitin transfer from the E2 enzyme to a substrate lysine residue is depicted below.

Detailed Methodologies

Reagent Preparation and Purification

1. Ubiquitin Proteins:

- Wild-Type Ubiquitin: Recombinantly expressed and purified. Store in aliquots at -80°C.

- K0 Ubiquitin: All seven lysines (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) mutated to arginine. Confirm the absence of chain-forming activity via mass spectrometry and Western blotting before use.

2. Enzymatic Components: