Optimized Western Blotting for High Molecular Weight Ubiquitinated Proteins: A Complete Guide from Theory to Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to reliably detect high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins via immunoblotting.

Optimized Western Blotting for High Molecular Weight Ubiquitinated Proteins: A Complete Guide from Theory to Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to reliably detect high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins via immunoblotting. Detecting these large ubiquitin conjugates is notoriously challenging due to inefficient transfer from gels and the inherent complexity of ubiquitin signaling. We address these hurdles by integrating foundational knowledge of ubiquitin biochemistry with optimized wet-lab protocols, advanced enrichment techniques, and rigorous validation strategies. Covering everything from SDS-PAGE optimization and affinity purification to troubleshooting smeared bands and confirming ubiquitination status, this resource delivers a complete methodological framework to advance research in cancer, neurodegeneration, and targeted protein degradation.

Understanding the Unique Challenges of High Molecular Weight Ubiquitinated Proteins

Why High MW Ubiquitinated Proteins Are Problematic in Western Blotting

Ubiquitination, the process where a small protein called ubiquitin is attached to a substrate protein, is a crucial post-translational modification regulating numerous cellular pathways. While studying this modification via Western blotting is common, researchers frequently encounter significant challenges, especially with high molecular weight (HMW) ubiquitinated proteins. These challenges stem from the inherent size of the proteins and the nature of the ubiquitin modification itself, often leading to unreliable data and failed experiments. This guide details the specific problems and provides targeted troubleshooting advice to improve the detection of these elusive targets.

FAQ: Understanding the Core Challenges

Q1: Why do I see smeared bands or ladders when blotting for ubiquitinated proteins?

This is a classic characteristic of ubiquitinated proteins and, paradoxically, a sign of successful detection. A ubiquitinated protein sample is not a uniform population. A single substrate protein can be modified by:

- Monoubiquitination: A single ubiquitin attachment.

- Polyubiquitination: A chain of ubiquitins attached to a single site.

- Multi-monoubiquitination: Multiple single ubiquitins attached to different sites on the same substrate.

Each of these states has a different molecular weight, causing the protein to run as a series of closely spaced bands that appear as a smear or ladder on the blot. Furthermore, polyubiquitin chains can be linked through different lysine residues, adding to the heterogeneity [1] [2].

Q2: Why is it particularly difficult to transfer high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins to a membrane?

The transfer of proteins from the gel to the membrane is a major bottleneck for HMW targets. The primary reasons include:

- Slow Migration: Large proteins migrate more slowly through the dense gel matrix during electrophoresis and are less efficiently eluted from the gel during the transfer step [3] [4].

- Gel Entrapment: HMW proteins can become physically trapped in the gel matrix, failing to transfer onto the membrane at all. This is especially true if standard protocols designed for smaller proteins are used [5].

Q3: How can I be sure my antibody is specifically detecting ubiquitin?

A significant problem in the field is the variable quality of commercial ubiquitin antibodies. Different antibodies may have specific preferences; some are better at detecting free ubiquitin, while others are more sensitive to ubiquitinated proteins or specific polyubiquitin chain linkages [6]. Always check the validation data provided by the manufacturer and, if possible, use a positive control, such as purified ubiquitinated proteins, to verify antibody performance [6].

Troubleshooting Guide

The table below summarizes common issues, their causes, and solutions for detecting HMW ubiquitinated proteins.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Incomplete transfer of HMW protein from gel to membrane [3] [4]. | - Use low-percentage acrylamide gels (e.g., 3-8% Tris-acetate) for better separation and transfer [3].- Increase transfer time; 8-10 minutes for rapid dry transfer, 3-4 hours for wet transfer [3] [7].- Add 0.01-0.05% SDS to the transfer buffer to help elute proteins from the gel [5] [8]. |

| Insufficient antigen (ubiquitinated protein) present [9]. | - Load more total protein (e.g., ≥20 µg per lane) [4] [7].- Enrich for ubiquitinated proteins prior to blotting using specific affinity resins (e.g., TUBEs, OtUBD) [10] [2]. | |

| High Background | Antibody concentration is too high [9] [8]. | Titrate both primary and secondary antibody concentrations to find the optimal dilution. |

| Incompatible or insufficient blocking [8] [7]. | - Optimize blocking time (1 hr at room temp or overnight at 4°C).- Test different blocking buffers (e.g., BSA vs. non-fat milk). Avoid milk when using primary antibodies derived from goat or sheep [9]. | |

| Smeared Bands | Natural heterogeneity of ubiquitin modifications [1] [2]. | This is often expected. To confirm specificity, treat samples with deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs); the smear should collapse into a discrete lower molecular weight band [10]. |

| Protein degradation during sample preparation [7]. | - Always use fresh protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, leupeptin) in lysis buffer [7].- Include N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes and preserve ubiquitin conjugates [10]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocol for HMW Ubiquitinated Proteins

The following protocol is tailored to maximize the detection of HMW ubiquitinated proteins, integrating key optimizations from general troubleshooting guides.

Stage 1: Gel Electrophoresis

- Gel Selection: Use a 3-8% Tris-acetate gel or a low-percentage Bis-Tris gel. These gels have a more open matrix that allows for better separation and migration of HMW proteins compared to standard Tris-glycine gels [3].

- Sample Preparation:

- Use a lysis buffer containing 8 M urea or another strong denaturant to disrupt protein interactions and inhibit enzymes [6] [2].

- Include protease inhibitors and 10-20 mM NEM to inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes and preserve the ubiquitination state [10].

- Boil samples in SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing a reducing agent (e.g., DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) for 5-10 minutes [9].

- Loading and Running: Load at least 20-30 µg of total protein per lane [4] [7]. Run the gel using pre-chilled buffer and surround the tank with ice packs to prevent overheating, which can cause band smearing [4].

Stage 2: Membrane Transfer (Optimized for HMW Proteins)

- Gel Equilibration: After electrophoresis, equilibrate the gel in transfer buffer for 10-15 minutes. For gels other than Tris-acetate, a 10-minute equilibration in 20% ethanol can improve HMW protein transfer efficiency by adjusting the gel size and removing buffer salts [3].

- Membrane Preparation: Activate a PVDF membrane in 100% methanol for 15 seconds, then equilibrate it in transfer buffer along with the filter paper and sponges [4].

- Transfer Conditions: For a standard wet transfer system:

Stage 3: Immunodetection

- Blocking: Block the membrane for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C with 5% non-fat dry milk or BSA in TBST [8] [7].

- Antibody Incubation:

- Primary Antibody: Incubate with a ubiquitin antibody that has been validated for detecting ubiquitinated proteins. Refer to the datasheet for the recommended dilution buffer (BSA or milk), as this can be antibody-specific [6] [7].

- Washing: Wash the membrane three times for 10 minutes each with TBST.

- Secondary Antibody: Incubate with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature [4].

- Detection: Use a high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrate. For low-abundance targets, a femto-level substrate may be necessary [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and tools essential for successful research on HMW ubiquitinated proteins.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Tris-Acetate Gels | Provides a more open gel matrix than Tris-glycine gels, enabling superior separation and transfer efficiency for HMW proteins [3]. |

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Tools (e.g., OtUBD, TUBEs) | Affinity resins used to selectively purify ubiquitinated proteins from complex lysates, enriching for low-abundance targets before Western blotting [10] [2]. |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | A deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) inhibitor. Added to lysis buffers to prevent the removal of ubiquitin from substrates during sample preparation, preserving the native ubiquitination state [10]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) | Used in cell culture treatments to prevent the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome, thereby increasing their intracellular levels for easier detection [6]. |

| Validated Ubiquitin Antibodies | Critical for specific detection. Antibodies should be chosen based on their validated performance for the specific application (e.g., detecting polyubiquitin chains vs. monoubiquitination) [6]. |

| PNGase F | An enzyme that removes N-linked glycans. Used to determine if a higher-than-expected molecular weight band is due to glycosylation rather than, or in addition to, ubiquitination [1] [7]. |

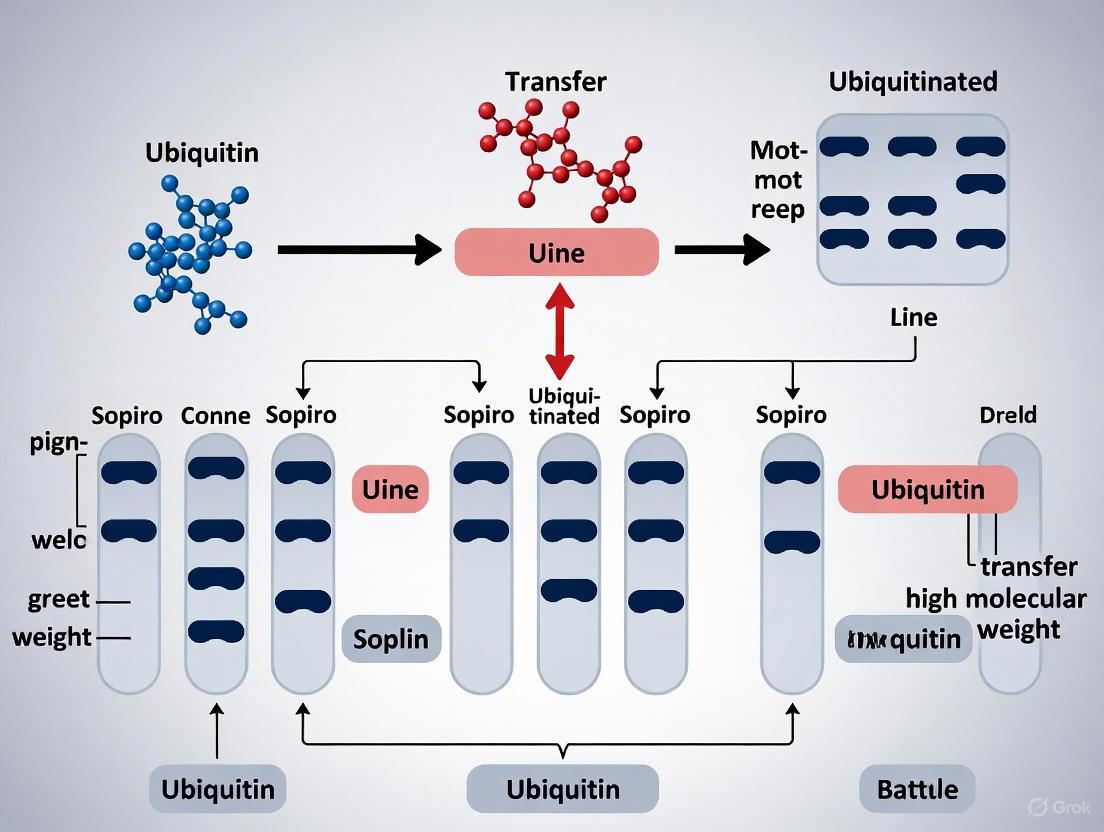

Visualizing the Workflow and Challenge

The following diagram illustrates the optimized workflow for detecting HMW ubiquitinated proteins, highlighting the key challenging steps.

Optimized HMW Ubiquitin Detection Workflow

The ubiquitination process is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates protein degradation and function via a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [11]. This process progresses from monoubiquitination to the assembly of complex polyubiquitin chains, with Lys48-linked chains primarily targeting proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome [11]. For researchers studying these processes, western blotting presents significant technical challenges, particularly for high molecular weight (HMW) ubiquitinated proteins and protein complexes. Efficient transfer and immunodetection of these large targets require specialized methodologies beyond standard protocols. This technical support center addresses these specific experimental hurdles with targeted troubleshooting and optimized procedures to improve the reliability of ubiquitination research.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Protein Transfer Issues for HMW Ubiquitinated Proteins

Q: My high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins (>150 kDa) show weak or no signal after transfer. What could be wrong?

A: This common problem typically stems from inefficient transfer out of the gel matrix. HMW proteins migrate more slowly and require optimized conditions for complete transfer [3].

- Increase Transfer Time: Standard transfer times are often insufficient. Extend transfer times to 3-4 hours for wet tank systems or 8-10 minutes for rapid dry transfer systems [12] [3].

- Optimize Transfer Buffer: Reduce methanol content to 5-10% to facilitate the movement of large proteins out of the gel [12]. For extremely large complexes (>250 kDa), consider adding 0.01-0.05% SDS to help proteins elute from the gel [8].

- Verify Transfer Efficiency: Always confirm successful transfer using reversible stains like Ponceau S or specific protein stains before proceeding to immunodetection [9] [13].

Q: I see smearing or poor resolution of polyubiquitin chains on my blots. How can I improve this?

A: Smearing can result from several factors, including incomplete denaturation, protein aggregation, or suboptimal gel conditions.

- Optimize Denaturation: Ensure complete protein denaturation by heating samples at 70-100°C for 10 minutes in Laemmli buffer [14]. For heat-sensitive proteins, consider longer incubation at lower temperatures (37°C for 30-60 minutes) [13].

- Use Appropriate Gel Chemistry: Standard Tris-glycine gels compress HMW proteins. Switch to Tris-acetate gels (3-8%) or low-percentage Bis-Tris gels (4-6%) for better separation [3] [14].

- Prevent Aggregation: Ensure samples contain adequate SDS and reducing agents (fresh DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) to disrupt non-covalent interactions [9].

Signal Detection Problems

Q: I get high background that obscures specific ubiquitin signals. How can I reduce this?

A: High background typically stems from non-specific antibody binding or suboptimal blocking.

- Optimize Blocking: Block membranes for at least 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [15]. For phospho-specific antibodies, use BSA instead of milk-based blockers [8].

- Titrate Antibodies: High antibody concentrations cause background. Dilute primary and secondary antibodies to the minimum necessary concentration [9].

- Enhance Washing: Increase wash stringency with TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20) rather than PBS, and include 0.05% Tween-20 in wash buffers [12] [8].

Q: My positive controls work, but my experimental samples show weak or no signal despite known ubiquitination. What should I check?

A: This discrepancy suggests issues with antigen accessibility or abundance in your specific samples.

- Verify Protein Integrity: Ubiquitinated proteins are susceptible to degradation. Always include fresh protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, leupeptin) and phosphatase inhibitors in lysis buffers [12] [16].

- Confirm Antigen Presence: Ensure sufficient protein loading (at least 20-30 μg for total proteins, up to 100 μg for modified targets in tissue extracts) [12].

- Check Membrane Compatibility: For low-abundance targets, use PVDF membranes with 0.2 μm pore size for better retention [4].

Specificity and Band Pattern Issues

Q: I see multiple unexpected bands when probing for ubiquitin. Are these non-specific?

A: Multiple bands may represent biologically relevant ubiquitin conjugates or technical artifacts.

- Understand Ubiquitination Patterns: Polyubiquitin chains can create laddering patterns due to different chain lengths [11]. Monoubiquitination or multi-monoubiquitination can also create discrete higher molecular weight species.

- Include Proper Controls: Run negative controls including (1) non-transfected cell lysates, (2) primary antibody omitted, and (3) secondary antibody only to identify non-specific bands [9].

- Confirm Antibody Specificity: Check antibody specifications for known cross-reactivities. Some ubiquitin antibodies may detect ubiquitin-like modifiers or related proteins [9].

Experimental Optimization Data Tables

Table 1: Transfer Conditions for Different Protein Sizes

| Protein Size Range | Gel Recommendation | Transfer Method | Transfer Time | Buffer Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 kDa | 4-20% Tris-glycine | Semi-dry | 45-60 min | 20% methanol [13] |

| 50-150 kDa | 8-12% Bis-Tris | Wet tank | 1-2 hours | 10-15% methanol [4] |

| 150-300 kDa | 3-8% Tris-acetate | Wet tank | 3-4 hours | 5-10% methanol, 0.01% SDS [12] [3] |

| >300 kDa | 3-8% Tris-acetate | Wet tank | 4-16 hours | 5% methanol, 0.05% SDS [14] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Signal Detection Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No signal | Insufficient transfer | Increase transfer time; Verify with Ponceau S [9] |

| Low antigen abundance | Load more protein (up to 100 μg); Enrich via IP [12] | |

| Antibody concentration too low | Increase primary antibody concentration; Extend incubation [8] | |

| High background | Incomplete blocking | Extend blocking time; Change blocking reagent [8] |

| Antibody concentration too high | Titrate antibodies; Reduce concentration [9] | |

| Insufficient washing | Increase wash number/duration; Add Tween-20 [8] | |

| Multiple bands | Protein degradation | Add fresh protease inhibitors [12] |

| PTMs (glycosylation, phosphorylation) | Consult databases (PhosphoSitePlus); Use specific enzymes [12] | |

| Non-specific antibody binding | Include species-specific controls; Use cross-adsorbed secondaries [9] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Optimized Western Blot Protocol for HMW Ubiquitinated Proteins

Sample Preparation

- Lysis: Use RIPA buffer supplemented with fresh protease inhibitors (1 μg/ml leupeptin, PMSF) and phosphatase inhibitors (2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1.0 mM beta-glycerophosphate, 2.5 mM sodium orthovanadate) [12] [16].

- Denaturation: Heat samples at 70-100°C for 10 minutes in 2X Laemmli buffer [14].

- Protein Quantification: Use BCA assay to ensure equal loading of 20-100 μg per lane, depending on target abundance [16].

Gel Electrophoresis

- Gel Selection: Use 3-8% Tris-acetate gels or 4-6% Tris-glycine gels for optimal HMW protein separation [3] [14].

- Electrophoresis Conditions: Run at constant voltage (100-150V) with cooling to prevent overheating and smearing [13].

Protein Transfer

- Membrane Preparation: Activate PVDF membrane in methanol for 15 seconds, then equilibrate in transfer buffer [4].

- Transfer Stack Assembly: Assemble transfer stack in this order: cathode, sponge, filter papers, gel, membrane, filter papers, sponge, anode [15].

- Transfer Conditions: Use wet transfer at 4°C for 3-4 hours at 70V (200-250mA) in transfer buffer with 5-10% methanol [12] [4].

Immunodetection

- Blocking: Block with 5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature [12].

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with primary antibody diluted in recommended buffer (BSA or milk) overnight at 4°C with agitation [15].

- Washing: Wash 3 times for 10 minutes each with TBST [4].

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature [15].

- Detection: Use enhanced chemiluminescence with appropriate exposure times [4].

Visualization of Key Concepts

Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

HMW Protein Western Blot Workflow

HMW Protein Western Blot Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ubiquitination Immunoblotting

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, Leupeptin, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevent degradation of ubiquitinated proteins during extraction [12] [16] |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors | Sodium orthovanadate, Beta-glycerophosphate | Preserve phosphorylation states that may regulate ubiquitination [12] |

| Gel Systems | Tris-acetate gels (3-8%), Low-percentage Bis-Tris gels | Improve separation and resolution of HMW ubiquitin conjugates [3] |

| Transfer Membranes | PVDF (0.2μm pore), Nitrocellulose | Optimize retention of HMW proteins; PVDF offers better binding capacity [4] |

| Detection Substrates | Enhanced chemiluminescence, Fluorescent substrates | Enable sensitive detection of low-abundance ubiquitinated species [8] |

| Ubiquitin-specific Antibodies | Mono-Ub, K48-Ub, K63-Ub specific antibodies | Distinguish between different ubiquitination types and chain linkages [11] |

Mastering the biochemistry of ubiquitination from monoubiquitination to complex polyubiquitin chains requires careful attention to technical details in western blotting. The challenges inherent in working with high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins can be systematically addressed through optimized transfer conditions, appropriate gel selection, and rigorous antibody validation. By implementing the troubleshooting strategies and detailed protocols outlined in this technical support guide, researchers can significantly improve the reliability and interpretability of their ubiquitination immunoblotting data, thereby advancing our understanding of this crucial regulatory pathway in cellular function and disease.

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common Western Blot Anomalies

FAQ 1: Why does my western blot show a ladder-like pattern of multiple discrete bands instead of a single sharp band?

A ladder-like pattern, a series of bands at regular molecular weight intervals, often indicates a specific biological process or an experimental artifact.

- Post-Translational Modification (PTM): The most common cause for a genuine ladder is the addition of multiple ubiquitin molecules, known as polyubiquitination. Each ubiquitin moiety adds approximately 8.6 kDa to the protein's mass [17]. Similar patterns, though less regular, can be seen with other PTMs like SUMOylation.

- Protein Isoforms: Some genes produce multiple protein isoforms through alternative splicing. These isoforms have slightly different molecular weights and can appear as a set of distinct bands [18] [17].

- Contamination: If the ladder pattern corresponds exactly to your protein molecular weight standard, it may indicate antibody cross-reactivity with the standard itself.

FAQ 2: What causes a smeared or diffuse band across the lane?

Smearing appears as a continuous, streaky signal from the top to the bottom of the lane and typically points to issues with sample integrity or gel electrophoresis.

- Protein Degradation: Protease activity in the sample post-lysis is a primary culprit. Degradation creates a heterogeneous mixture of full-length and partially digested protein fragments, resulting in a smear [18] [13].

- Protein Aggregation: Proteins, especially hydrophobic or membrane-bound ones, can form aggregates that do not resolve cleanly during SDS-PAGE, leading to high molecular weight smearing [8] [17].

- Overloading: Loading too much protein per lane can overwhelm the gel's resolving capacity, causing the protein band to spread vertically [8] [18].

- Incomplete Denaturation: If the sample was not properly boiled or reduced, the protein may not be fully linearized, leading to aberrant migration and smearing [9].

FAQ 3: My target band is at the wrong molecular weight. What are the reasons for this shift?

Observing a band at a molecular weight different from the calculated weight is very common and can be due to several factors.

- Post-Translational Modifications:

- Glycosylation: The addition of extensive sugar chains (N- or O-linked glycosylation) can significantly increase a protein's apparent molecular weight, often creating a broad, diffuse band or smear at a higher weight [17] [19].

- Phosphorylation: While the addition of a single phosphate group (~1 kDa) may not be resolved, hyperphosphorylation at multiple sites can cause a noticeable upward shift [17].

- Cleavage of Protein Domains:

- Signal Peptides: Many proteins have an N-terminal signal peptide that is cleaved off during maturation, causing the mature protein to run at a lower molecular weight than predicted from its full amino acid sequence [17].

- Pro-protein Processing: Inactive pro-proteins (e.g., caspases, matrix metalloproteinases) are cleaved to generate active forms, which will run at a lower molecular weight [17].

- Alternative Splice Variants: As mentioned above, different isoforms can run at higher or lower weights than the canonical sequence prediction.

- Protein Complexes: Even in denaturing conditions, some strong protein-protein interactions (e.g., disulfide-linked dimers) can persist, causing bands at multiples of the expected monomeric weight [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Data Tables

Table 1: Troubleshooting Band Patterns, Causes, and Solutions

| Band Pattern | Primary Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ladder Pattern | Polyubiquitination [17] | Confirm with ubiquitin-specific antibodies or proteasome inhibition. |

| Multiple protein isoforms [18] [17] | Consult databases (UniProt) for known isoforms; use isoform-specific antibodies. | |

| Smearing | Protein Degradation [18] [13] | Always use fresh protease/phosphatase inhibitors; keep samples on ice. |

| Protein Aggregation [8] [17] | Ensure sample is properly solubilized; sonicate samples; avoid overheating during denaturation [13]. | |

| Gel Overloading [8] [18] | Reduce the total amount of protein loaded per lane. | |

| Molecular Weight Shift | Glycosylation [17] [19] | Treat samples with glycosidases (e.g., PNGase F) to see if the band shifts down. |

| Pro-protein Cleavage [17] | Research the known maturation pathway of your protein; the observed size may be correct for the mature form. | |

| Persistent Dimers/Complexes [17] | Increase concentration of reducing agent (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) in loading buffer. |

Table 2: Optimizing Transfer for High Molecular Weight Ubiquitinated Proteins

A major challenge in studying high molecular weight (HMW) ubiquitinated proteins is their inefficient transfer from the gel to the membrane. The table below summarizes key parameters to optimize.

| Parameter | Problem | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Transfer Buffer | Methanol in buffer causes gel shrinkage, trapping HMW proteins [5]. | Reduce methanol concentration to 5-10% to improve elution of HMW proteins [19]. |

| Insufficient charge to pull large proteins out. | Add 0.01-0.04% SDS to the transfer buffer to increase protein mobility and aid elution [5] [19]. | |

| Transfer Method & Time | Standard transfer times are too short for HMW proteins. | Use a wet tank transfer system and extend transfer time to 3-4 hours or overnight at low voltage [13] [19]. |

| Membrane Choice | Proteins may bind poorly. | Use PVDF membrane due to its higher binding capacity for proteins [5]. |

| Post-Transfer Check | Assuming transfer was efficient without verification. | Always stain the gel post-transfer with Coomassie to check for residual protein, confirming transfer efficiency [8] [20]. |

Experimental Protocol: Confirming Ubiquitination

This protocol outlines a method to confirm whether a laddering pattern is due to polyubiquitination.

Title: Immunoblotting to Detect Polyubiquitinated Proteins

Objective: To confirm the presence of polyubiquitin chains on a protein of interest, characterized by a classic ladder pattern on a western blot.

Introduction: Ubiquitination is a key PTM regulating protein degradation and signaling. A ubiquitin ladder confirms polyubiquitination. This protocol uses a protein gel electrophoresis and western blot workflow with specific antibodies for detection.

Materials:

- Cell lysates (treated with a proteasome inhibitor like MG132 to enrich for ubiquitinated species)

- Lysis buffer with protease inhibitors and deubiquitinase inhibitors (e.g., N-Ethylmaleimide)

- SDS-PAGE gel (4-20% gradient gel recommended for better separation of HMW species)

- Primary antibody against your protein of interest

- Primary antibody against ubiquitin (e.g., Ubiquitin B) [17]

- HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

- ECL substrate

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Culture cells and treat with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., 10 µM MG132) for 4-6 hours before lysis to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins. Lyse cells in a suitable buffer (e.g., RIPA) supplemented with 1X protease inhibitor cocktail and 5-10 mM N-Ethylmaleimide to inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes [19].

- Protein Separation: Load 20-50 µg of total protein per lane on a 4-20% gradient polyacrylamide gel. This gel type provides superior resolution for high molecular weight complexes compared to fixed-percentage gels. Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 100-120V) until the dye front reaches the bottom.

- Protein Transfer: For wet transfer, use a transfer buffer containing 10% methanol and 0.01-0.02% SDS. Transfer at 4°C for 3-4 hours at 70V or overnight at 30V [19].

- Immunoblotting:

- Block the membrane with 5% BSA or non-fat milk in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Incubate with the primary antibody (against your target protein or ubiquitin) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Wash the membrane 3-5 times for 5 minutes each with TBST.

- Incubate with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Wash again thoroughly.

- Detection: Develop the blot using a sensitive ECL substrate. For low-abundance ubiquitinated species, a long exposure time (several minutes to hours) may be necessary.

Expected Outcome: A successful experiment will show a ladder of bands above the main protein band when probing for the target protein. The distance between bands will be approximately 8-10 kDa, corresponding to the addition of multiple ubiquitin molecules. Probing with an anti-ubiquitin antibody will show the same ladder pattern, confirming the modification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying HMW Ubiquitinated Proteins

| Reagent | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Blocks degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins, leading to their accumulation for easier detection. | MG-132, Lactacystin. Add to cell culture media 4-6 hours before lysis. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Prevents the removal of ubiquitin chains by DUBs during sample preparation, preserving the ladder pattern. | N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM), PR-619. Must be added fresh to the lysis buffer. |

| SDS-PAGE Gradient Gels | Provides a broad separation range, resolving both low and high molecular weight species on the same gel. | 4-20% or 3-8% Tris-Acetate gels. The latter is specifically designed for optimal resolution of HMW proteins. |

| Ubiquitin-Specific Antibodies | Used to directly confirm that a ladder pattern is due to ubiquitination. | Anti-Ubiquitin (e.g., Ubiquitin B) [17]. Monoclonal antibodies offer higher specificity. |

| PVDF Membrane | Has a high protein binding capacity and mechanical strength, ideal for retaining HMW proteins. | 0.45 µm pore size. Must be activated in methanol before use. |

| Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) Substrate | Provides the high sensitivity needed to detect low-abundance, ubiquitinated protein species. | "Femto" or "Maximum Sensitivity" substrates. Allows for detection of sub-picogram amounts of protein. |

Efficient transfer and strong membrane retention of proteins are critical steps in western blotting. For high molecular weight (HMW) ubiquitinated proteins, these processes present particular challenges. The large size of these protein complexes hinders their migration out of the gel matrix, while the complex structure of ubiquitin chains can complicate membrane binding. This guide addresses the specific hurdles researchers face when working with HMW ubiquitinated proteins and provides optimized protocols to overcome them.

FAQs: Troubleshooting Transfer and Retention Issues

How does protein size affect transfer efficiency?

Protein size significantly impacts transfer kinetics. HMW proteins (>150 kDa) migrate more slowly through the gel matrix during electrophoresis and require more time to transfer completely to the membrane [3]. Their large physical size means they can become trapped in the gel, leading to inefficient transfer. For ubiquitinated proteins, which can form even larger complexes through polyubiquitin chains, this problem is exacerbated [21].

Why do HMW ubiquitinated proteins present special challenges?

Ubiquitinated HMW proteins present dual challenges: their substantial size impedes electrophoretic transfer from the gel, and the hydrophilic nature of ubiquitin chains can reduce hydrophobic interactions with certain membrane types [21]. Additionally, the labile nature of ubiquitin modifications means that extended transfer times might increase the risk of protein degradation or deubiquitination [21].

What are the signs of poor transfer or retention in my western blots?

Key indicators include:

- Weak or absent signal for your target protein despite proper sample loading

- Signal decreasing with increasing molecular weight

- Protein visible in the gel after transfer (using post-transfer staining)

- Signal detected on a second membrane placed behind the first

- Inconsistent results for HMW proteins while smaller proteins detect normally

How can I confirm whether my transfer issues are due to inefficient transfer versus poor retention?

To diagnose the specific problem:

- Stain the gel after transfer with Coomassie Blue: significant protein remaining indicates inefficient transfer [22]

- Use a double membrane setup: protein detection on the second membrane indicates blow-through due to poor retention [22]

- Employ pre-stained molecular weight markers: track whether proteins of different sizes are transferring effectively [22]

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Specific Issues

Problem: Incomplete Transfer of HMW Proteins

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient transfer time: HMW proteins require extended transfer times; increase transfer duration by 25-50% [3]

- Inappropriate gel composition: Use Tris-acetate gels or low-percentage Bis-Tris gels (3-8%) instead of standard Tris-glycine gels for better separation of HMW proteins [3]

- Suboptimal transfer method: Wet transfer systems generally provide better efficiency for HMW proteins than semi-dry systems [23] [24]

- Excessive heat generation: Ensure adequate cooling during transfer to prevent protein degradation or gel distortion

Problem: Poor Membrane Retention of Transferred Proteins

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inappropriate membrane selection: PVDF membranes generally provide superior binding capacity for HMW proteins compared to nitrocellulose [25] [24]

- Incorrect pore size: For HMW proteins, use membranes with 0.2 µm pores instead of 0.45 µm to prevent blow-through [25]

- Inadequate membrane preparation: Ensure proper activation of PVDF membrane in methanol before use [25]

- Improper buffer composition: Optimize methanol content (typically 10-20%) to enhance protein binding while maintaining transfer efficiency [25]

Problem: Specific Issues with Ubiquitinated Proteins

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Lability of ubiquitin modifications: Include deubiquitinase inhibitors in your transfer buffer to preserve ubiquitin signals [21]

- Reduced hydrophobic interaction: Consider using specialized membranes with higher binding capacity for hydrophilic proteins

- Multiple banding patterns: This may reflect different ubiquitination states; ensure adequate separation using appropriate gel percentages

Optimized Protocols for HMW Ubiquitinated Proteins

Protocol 1: Wet Transfer Method for HMW Proteins

Materials:

- Transfer buffer: 25 mM Tris Base, 195 mM glycine, 10-15% methanol [25]

- PVDF membrane (0.2 µm pore size) [25]

- Tris-acetate gel (3-8%) or low-percentage Bis-Tris gel [3]

- Filter paper and transfer apparatus

Method:

- Gel equilibration: After electrophoresis, equilibrate gel in transfer buffer for 15 minutes with agitation [25]

- Membrane activation: Wet PVDF membrane in 100% methanol for 30 seconds, then equilibrate in transfer buffer [25]

- Sandwich assembly: Assemble transfer stack in the following order (cathode to anode):

- Remove air bubbles: Roll each layer gently with a roller or pipette to eliminate air bubbles [25]

- Transfer conditions: Transfer at constant voltage (75-100V) for 90-120 minutes with cooling [25] [3]

- Post-transfer processing: Rinse membrane briefly with TBS before blocking [25]

Protocol 2: Rapid Dry Transfer Optimization

Materials:

- iBlot 2 Transfer Stack or equivalent

- Tris-acetate gel (3-8%)

- Transfer apparatus

Method:

- Gel preparation: If not using Tris-acetate gels, pre-equilibrate gel in 20% ethanol for 5-10 minutes [3]

- Stack assembly: Assemble gel and transfer stack according to manufacturer instructions

- Transfer parameters: Use extended transfer time (8-10 minutes at 20-25V) instead of standard 7-minute program [3]

- Program selection: For HMW proteins (>150 kDa), use P0 or P3 program with extended time [3]

Protocol 3: Verification of Transfer Efficiency

Materials:

Method for Double-Membrane Test:

- Extra membrane setup: Place a second PVDF membrane directly behind the first membrane in your transfer stack [22]

- Standard transfer: Perform transfer using your standard protocol

- Process both membranes: Block and probe both membranes separately with your target antibody

- Interpretation: Signal primarily on first membrane indicates good retention; significant signal on second membrane indicates blow-through and need for optimized conditions [22]

Method for Post-Transfer Gel Staining:

- Standard transfer: Perform transfer with your test samples

- Gel staining: After transfer, stain the gel with Coomassie Blue for 30-60 minutes [22]

- Destain: Destain until background is clear and protein bands are visible

- Interpretation: Significant protein remaining in gel indicates incomplete transfer [22]

Quantitative Transfer Optimization Data

Table 1: Transfer Efficiency Comparison for Different Protein Sizes

| Protein Size | Optimal Gel Type | Transfer Method | Recommended Time | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 kDa | 4-20% Tris-glycine | Semi-dry | 45-60 min | High [25] |

| 50-150 kDa | 4-20% Tris-glycine | Wet or semi-dry | 60-75 min | High [25] |

| >150 kDa | 3-8% Tris-acetate | Wet transfer | 90-120 min | Moderate-High [3] |

| >150 kDa | 4-12% Bis-Tris | Wet transfer | 90-120 min | Moderate [3] |

| Ubiquitinated HMW | 3-8% Tris-acetate | Wet transfer | 90-120 min | Moderate (method-dependent) |

Table 2: Comparison of Western Blot Transfer Methods

| Parameter | Wet Transfer | Semi-Dry Transfer | Dry Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Time | 30-120 min [23] | 7-10 min [23] | As few as 3 min [23] |

| Buffer Requirements | Requires methanol (~1000 mL) [23] | Methanol-free transfer buffers (~200 mL) [23] | No buffer required [23] |

| Performance for HMW Proteins | +++ [23] [24] | ++ [23] | +++ [23] |

| Ease of Use | ++ [23] | +++ [23] | +++ [23] |

| Cooling Required | Often [23] | Sometimes [23] | No [23] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for HMW Protein Western Blotting

| Reagent/Material | Function | Recommendation for HMW Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| PVDF Membrane | Protein binding surface | 0.2 µm pore size for better HMW protein retention [25] |

| Tris-Acetate Gels | Separation matrix | 3-8% gradient for optimal HMW protein separation [3] |

| Transfer Buffer | Conducting medium | 25 mM Tris, 195 mM glycine, 10-15% methanol [25] |

| Pre-stained Markers | Transfer monitoring | Multi-colored for tracking different size proteins [22] |

| Methanol | Membrane activation & buffer component | 100% for PVDF activation; 10-15% in transfer buffer [25] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent protein degradation | Include DUB inhibitors for ubiquitinated proteins [21] |

Visual Guide to Transfer Optimization

HMW Transfer Optimization Workflow

Problem-Solution Analysis

Successfully detecting high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins in western blotting requires careful optimization of both transfer efficiency and membrane retention. By implementing the diagnostic methods and optimized protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can systematically address the unique challenges posed by these complex protein species. The key considerations include selecting appropriate gel and membrane matrices, optimizing transfer times and conditions, and implementing verification steps to confirm successful protein transfer and retention. Through these targeted approaches, the technical hurdles of inefficient transfer and poor membrane retention can be effectively overcome, leading to more reliable and reproducible detection of HMW ubiquitinated proteins in research applications.

A Step-by-Step Optimized Protocol for Efficient Transfer and Detection

Efficient transfer of high molecular weight (HMW) ubiquitinated proteins during western blotting presents significant technical challenges that can compromise research outcomes. These large protein complexes migrate slowly through gel matrices and frequently require specialized transfer conditions to prevent entrapment and ensure complete movement from gel to membrane. The composition of your transfer buffer and maintenance of proper temperature conditions serve as critical reagents in this process, directly impacting the sensitivity and reliability of your immunoblotting results for ubiquitin research. This technical guide addresses the most common troubleshooting scenarios and provides optimized protocols to enhance detection of HMW ubiquitinated proteins in drug development applications.

Troubleshooting Guide: HMW Protein Transfer Issues

FAQ: Why do I get weak or no signals for my HMW ubiquitinated proteins?

Possible Cause: Incomplete transfer of large protein complexes from the gel to the membrane.

Solutions:

- Increase transfer time: For proteins >150 kDa, extend transfer times to 8-10 minutes for rapid dry systems or 3-4 hours for standard wet transfer systems [3] [26]. For overnight transfers, use 30V at 4°C [27].

- Optimize methanol concentration: Reduce methanol content in transfer buffer to 5-10% to enhance the movement of large proteins out of the gel [26]. Standard transfer buffers typically contain 15-20% methanol, which can impede HMW protein migration.

- Add SDS to transfer buffer: Include 0.01-0.05% SDS in your transfer buffer to help solubilize and pull large proteins from the gel matrix [8].

- Verify transfer efficiency: After transfer, stain the gel with a protein stain (such as Coomassie blue) to determine if protein remains in the gel [27] [8].

FAQ: Why do I see smearing or distorted bands for my HMW ubiquitinated proteins?

Possible Cause: Overheating during transfer causing protein degradation or uneven transfer.

Solutions:

- Use pre-chilled buffers and conditions: Always perform transfers at 4°C or use ice packs in the transfer chamber to prevent overheating [4] [27].

- Optimize gel composition: Use Tris-acetate gels (3-8%) instead of Bis-Tris or Tris-glycine gels for better separation and transfer of HMW proteins [3].

- Add an alcohol equilibration step: Submerge the gel in 20% ethanol for 5-10 minutes before transfer to remove contaminating electrophoresis buffer salts and prevent increased conductivity that generates heat [3].

FAQ: Why do my HMW proteins transfer inefficiently while smaller proteins over-transfer?

Possible Cause: Standardized transfer conditions that don't account for the different migration rates of various protein sizes.

Solutions:

- Implement sequential transfer protocols: Use an initial longer transfer at lower voltage for HMW proteins, followed by standard conditions for mid-range proteins.

- Optimize membrane pore size: For proteins >150 kDa, use membranes with 0.45μm pores rather than 0.2μm pores to better capture large protein complexes [28].

- Adjust gel concentration: Use lower percentage gels (e.g., 7.5% for proteins >200kDa) to create a more open matrix that facilitates HMW protein migration [28].

Optimized Transfer Buffer Compositions

Table 1: Transfer Buffer Formulations for HMW Ubiquitinated Proteins

| Buffer Type | Composition | Optimal Protein Size Range | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Towbin Buffer | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 15-20% methanol, pH 8.3 [25] | <100 kDa | Standard formulation; may require modification for HMW proteins |

| Low-Methanol Buffer | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 5-10% methanol, pH 8.3 [26] | >150 kDa | Enhanced transfer efficiency for HMW ubiquitinated complexes |

| SDS-Supplemented Buffer | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 10% methanol, 0.01-0.05% SDS, pH 8.3 [8] | >200 kDa | Helps solubilize large protein complexes; use with PVDF membranes |

| High-Salt Alternative | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.3 | 50-150 kDa | Can improve transfer of some membrane-associated ubiquitinated proteins |

Table 2: Transfer Conditions by Protein Size and System Type

| Protein Size | Wet Transfer Conditions | Semi-Dry Conditions | Rapid Dry Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| <50 kDa | 60-90 min at 100V, 4°C [4] | 30-45 min at 15V | 5-7 min at 20V [3] |

| 50-150 kDa | 90-120 min at 100V, 4°C [4] | 45-60 min at 15V | 7 min at 20-25V [3] |

| >150 kDa | 3-4 hours at 70V, 4°C or overnight at 30V, 4°C [27] [26] | 10-12 min at 15V [3] | 8-10 min at 20-25V [3] |

| >200 kDa | 4+ hours at 70V, 4°C with 0.01% SDS [26] | 12-15 min at 15V | 10 min at 25V [3] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized Wet Transfer for HMW Ubiquitinated Proteins

Materials:

- Pre-chilled transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 10% methanol, pH 8.3)

- PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane (0.45μm pore size)

- Filter paper, sponges, transfer apparatus

- Ice bath or cooling unit

Method:

- Following electrophoresis, equilibrate the gel in pre-chilled transfer buffer for 15 minutes with gentle agitation [25].

- Activate PVDF membrane in 100% methanol for 15 seconds, then equilibrate in transfer buffer for 5 minutes [4].

- Prepare transfer stack in the following order (from cathode to anode): sponge, filter paper, gel, membrane, filter paper, sponge [25].

- Remove air bubbles by rolling a glass tube or roller across the stack after each layer is added [27].

- Place the stack in the transfer tank filled with pre-chilled transfer buffer.

- Transfer at 70V for 3-4 hours at 4°C [26]. For particularly large complexes (>250 kDa), extend time to 4-5 hours or use overnight transfer at 30V [27].

- After transfer, verify efficiency by reversible membrane staining or gel staining.

Protocol 2: Rapid Dry Transfer Optimization for HMW Proteins

Materials:

- iBlot 2 or similar rapid transfer system

- Appropriate transfer stacks

- 20% ethanol solution

Method:

- Following electrophoresis, equilibrate the gel in 20% ethanol for 10 minutes with agitation [3].

- Assemble the transfer stack according to manufacturer instructions.

- Use pre-programmed method P0 or P3 at 20-25V for 8-10 minutes (extended from standard 7-minute protocol) [3].

- For proteins >200 kDa, consider running two consecutive transfer cycles.

- After transfer, process membrane for immunodetection.

Protocol 3: Transfer Efficiency Validation

Materials:

- Ponceau S solution or reversible protein stain

- Coomassie blue gel stain

Method:

- After transfer, stain the membrane with Ponceau S to visualize total transferred protein [28].

- Document the staining to confirm even transfer and presence of HMW proteins.

- Destain the membrane before proceeding to blocking.

- Alternatively, stain the gel post-transfer with Coomassie blue to detect any proteins remaining in the gel [27].

- Compare the intensity of molecular weight markers between gel and membrane to assess transfer efficiency.

Diagram 1: HMW Protein Transfer Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Critical Reagents for HMW Ubiquitinated Protein Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Recommendations for HMW Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Tris-Acetate Gels | Superior separation of HMW proteins | Use 3-8% gradient Tris-acetate gels for optimal resolution of proteins >150 kDa [3] |

| PVDF Membrane | Protein binding surface | Use 0.45μm pore size for HMW proteins; activate with methanol before use [4] [25] |

| Transfer Buffer Modifiers | Enhance protein mobility | Reduce methanol to 5-10%; add 0.01-0.05% SDS for difficult-to-transfer complexes [26] [8] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent protein degradation | Include comprehensive protease inhibitor cocktails to preserve ubiquitin linkages [26] [28] |

| Cooling Systems | Maintain optimal temperature | Use pre-chilled buffers and transfer at 4°C to prevent overheating [4] [27] |

| Ubiquitin-Specific Antibodies | Target detection | Validate antibodies for denatured proteins; check species reactivity [26] |

Advanced Techniques for Challenging Targets

For particularly difficult-to-transfer HMW ubiquitinated complexes, consider these advanced approaches:

Two-Stage Transfer Protocol:

- Stage 1: 1 hour at 100V with low-methanol buffer (5%) to move HMW proteins from gel

- Stage 2: 1 hour at 100V with standard methanol concentration (15%) to transfer mid-range proteins

Alternative Buffer Systems:

- CAPS buffer (10 mM CAPS, 10% methanol, pH 11.0) can improve transfer of some HMW proteins

- Bicine buffer systems may enhance transfer efficiency for membrane-associated ubiquitinated proteins

Membrane Activation Techniques:

- For PVDF: Extended methanol activation (2-3 minutes) may improve binding of HMW complexes

- For nitrocellulose: Consider ethanol activation instead of methanol for specific applications

Always validate any modified protocol with known positive controls and verify transfer efficiency through post-transfer gel staining. Consistent temperature maintenance through pre-chilled buffers and apparatus remains critical throughout these optimizations.

In immunoblotting research, particularly for the study of high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins, the initial step of gel electrophoresis is critical. The choice of acrylamide percentage and gel type directly influences the resolution, transfer efficiency, and ultimate success of your experiment. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and protocols to optimize this foundational step, ensuring clear separation and reliable detection of complex protein targets.

FAQs: Core Principles of Gel Selection

1. How does acrylamide percentage affect my protein separation? The acrylamide concentration in a gel determines the pore size of its matrix, which controls how easily proteins of different sizes can migrate.

- Low percentage gels (e.g., 6-8%) have larger pores, ideal for the efficient migration and separation of high molecular weight (MW) proteins (>150 kDa).

- High percentage gels (e.g., 12-15%) have smaller pores, providing better resolution for low MW proteins (<30 kDa) or closely sized bands.

- Gradient gels (e.g., 4-20%) contain a continuous range of acrylamide percentages, offering a broad separation range and sharpening protein bands across a wide mass spectrum [29].

2. What gel percentage should I use for ubiquitinated proteins? Ubiquitinated proteins can present as monomers or as part of higher molecular weight complexes and polyubiquitin chains. The optimal gel percentage depends on the specific size of your target.

- For detecting free ubiquitin monomers (8.5 kDa), a high-percentage gel (12-15%) is recommended [29].

- For studying polyubiquitinated proteins or protein complexes, which can be very large (>150 kDa), a lower percentage gel (6-8%) or a gradient gel is more appropriate [29].

- When the size range is unknown or you are analyzing multiple ubiquitinated species, a 4-20% gradient gel is the most versatile choice [29].

3. Why should I consider a gradient gel for my research? Gradient gels offer several key advantages for ubiquitination research:

- Wide Separation Range: They can resolve proteins from very small (10 kDa) to very large (200+ kDa) on a single gel, which is ideal for capturing various ubiquitin conjugates [29].

- Superior Band Sharpness: As proteins migrate, they reach a pore size where their movement is hindered, sharpening the bands and improving resolution.

- Streamlined Workflow: They eliminate the need to run multiple single-percentage gels when analyzing targets of diverse sizes.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Resolution or Smeared Bands

Poorly defined bands can obscure critical results and prevent accurate analysis.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incorrect Gel Percentage | Match the gel percentage to your protein's MW. Use a higher % for small proteins and a lower % for large proteins [29]. |

| Voltage Too High | Run the gel at a lower voltage (e.g., 10-15 V/cm). High voltage causes overheating and smearing [30]. |

| Overloaded Sample | Load less protein. Higher % gels are less forgiving of overloading [29]. |

| Improper Running Buffer | Remake the running buffer to ensure correct ion concentration and pH for proper current flow [30]. |

| Old or Improperly Prepared Sample | Use fresh reducing agents (DTT/BME), avoid excessive salt, and ensure samples are boiled properly [31]. |

Problem 2: "Smiling" or Curved Bands

Bands that curve upward at the edges are often a result of uneven heat distribution.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Excessive Heat Generation | Run the gel in a cold room, use a cooling apparatus, or reduce the voltage and extend the run time [30]. |

| Gel Degradation | Check the expiration date of precast gels and store them according to manufacturer specifications [31]. |

Problem 3: Protein Samples Migrated Off the Gel

This occurs when the electrophoresis run is continued for too long.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Gel Run Too Long | Stop the run when the dye front is about to reach the bottom of the gel. For high MW targets, you may need to run longer, but monitor carefully [30]. |

Problem 4: Distorted Bands on the Gel's Edge (Edge Effect)

Lanes on the periphery of the gel show distorted band patterns.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Empty Wells | Avoid leaving wells empty. Load a dummy sample, ladder, or loading buffer into unused wells to ensure even current flow across the entire gel [30]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing SDS-PAGE for High Molecular Weight Ubiquitinated Proteins

Objective: To achieve clear separation of high molecular weight proteins (>150 kDa) for subsequent western blotting.

Materials:

- Precast gel (6-8% single percentage or 4-20% gradient) [29]

- Appropriate SDS-PAGE running buffer (e.g., 1X Tris-Glycine-SDS)

- Prestained protein molecular weight ladder

- Protein samples in 1X or 2X Laemmli buffer

- Electrophoresis tank and power supply

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute protein samples in Laemmli buffer containing fresh reducing agent (e.g., DTT or BME). Heat denature at 95°C for 5 minutes. Centrifuge briefly to collect condensation.

- Gel Setup: Remove the comb and rinse wells with running buffer. Place the gel into the electrophoresis tank and fill the inner and outer chambers with running buffer, ensuring wells are completely submerged.

- Loading and Run: Load samples and ladder into wells. For large gels, load quickly to prevent sample diffusion. Connect the power supply and run the gel. For a 6-8% gel, use a constant voltage of 100-150V. Crucially, for high MW proteins, run the gel until the target protein has migrated sufficiently, even if the dye front runs off. Monitor the migration of the prestained ladder [30] [29].

- Post-Run: Proceed to western blot transfer.

Troubleshooting Note: If bands are smeary, check sample concentration (avoid overloading), ensure running buffer is fresh, and confirm the gel percentage is appropriate for your protein size [29].

Protocol 2: In-Gel Fluorescence Detection as an Alternative to Western Blotting

Objective: To directly detect a tagged recombinant protein in a polyacrylamide gel with high sensitivity and quantitative accuracy, bypassing the transfer and antibody steps of western blotting [32].

Materials:

- Connectase enzyme and Cy5.5-conjugated peptide substrate (for CnTagged proteins) [32]

- Protein samples with N-terminal CnTag

- Standard SDS-PAGE equipment and fluorescence gel scanner

Method:

- Conjugate Formation: Incubate equimolar concentrations (5 µM) of Connectase and the fluorescent peptide substrate for 1 minute to form the N-terminal fluorophore-Connectase conjugate (N-Cnt) [32].

- Protein Labeling: Mix a small volume of the N-Cnt reagent (final ~1.67 nM) with your protein sample. Incubate for 5-30 minutes at room temperature. The reaction works in various buffers, including RIPA lysis buffer [32].

- Electrophoresis and Imaging: Separate the samples on a polyacrylamide gel. Visualize the directly labeled proteins using a fluorescence imager or scanner [32].

Advantages: This method is faster than western blotting, offers a superior signal-to-noise ratio, allows for more reproducible and accurate quantifications, and does not require protein-specific antibodies [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following reagents are fundamental for gel electrophoresis and advanced detection techniques in protein analysis.

| Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Precast Gels (6-15%, 4-20% Gradients) | Provides a consistent, optimized matrix for protein separation based on molecular weight. Saves preparation time [29]. |

| Tris-Glycine-SDS Running Buffer | Maintains pH and ion concentration for proper current flow during electrophoresis. Essential for protein separation [30] [29]. |

| Connectase & CnTag System | A highly specific protein ligase used for direct, antibody-free fluorescence detection of tagged proteins within gels [32]. |

| CHIPΔTPR E3 Ligase Domain | A potent UPS-interacting domain derived from the CHIP E3 ligase, used in the construction of bioPROTACs for targeted protein degradation studies [33]. |

| Fresh Reducing Agents (DTT/BME) | Prevents re-oxidation of proteins during sample preparation and gel running, ensuring proper unfolding and migration [31]. |

Visual Guide: Experimental Workflow and Optimization Logic

The diagram below outlines the key decision points and steps for optimizing your gel electrophoresis setup.

For researchers focusing on high molecular weight (HMW) ubiquitinated proteins, mastering the wet transfer method is a critical step in immunoblotting. Efficiently moving these large protein complexes (>150 kDa) from the gel to a membrane is often a bottleneck, as standard protocols optimized for smaller proteins can lead to incomplete transfer and weak detection signals. This guide details the optimized conditions for current, voltage, time, and temperature specifically for HMW proteins, providing a foundation for reliable and reproducible results in your research on ubiquitination and protein degradation pathways.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why is the wet transfer method preferred for high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins? Wet transfer is preferred because it provides more uniform and efficient transfer of large proteins. It generates less heat than semi-dry systems and allows for extended transfer times, which are often necessary for HMW proteins to migrate completely out of the gel and onto the membrane [23] [34] [15]. The ability to run the transfer at 4°C is also a key advantage for maintaining protein stability.

What is the purpose of conducting the transfer at 4°C? Running the transfer at 4°C is crucial for dissipating the significant heat generated during electrophoresis. This heat can cause protein degradation, create distorted "smiling" bands, and in extreme cases, melt the gel [4] [34] [15]. For HMW proteins, which require longer transfer times, temperature control is essential to prevent these artifacts.

My ubiquitinated proteins are detected at a much higher molecular weight than predicted. Is this normal? Yes, this is a common and expected observation. Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of one (mono-) or multiple (poly-) ubiquitin molecules (each ~8.6 kDa) to a target protein [35]. A ladder of bands at higher molecular weights is a classic signature of polyubiquitinated proteins and should not be considered a troubleshooting issue.

How can I confirm my protein transfer was successful before proceeding with antibody incubation? You can perform a reversible stain, such as Ponceau S, on the membrane after transfer [36] [9]. This stain allows you to visualize the total protein pattern, confirm the presence of your molecular weight marker, and check for any air bubbles that may have blocked transfer. The stain can then be washed away with TBST before you begin blocking.

Optimized Wet Transfer Protocol for HMW Proteins

The following protocol is tailored for the transfer of high molecular weight proteins, including ubiquitinated species [4] [34].

Pre-Transfer Steps

- Gel Equilibration: After SDS-PAGE, carefully immerse the gel in 1X transfer buffer for 10-40 minutes [36] [4]. This step removes electrophoresis salts and prevents gel expansion during transfer.

- Membrane Activation: For PVDF membranes, you must activate them by wetting in 100% methanol for 30 seconds, followed by a brief rinse in distilled water and soaking in transfer buffer [36] [34]. Note: Do not use methanol with nitrocellulose membranes.

- Sandwich Preparation: Soak sponges and filter papers in 1X transfer buffer. Assemble the transfer sandwich in the following order, carefully rolling out any air bubbles with a test tube or roller after each layer [36] [15]:

- Cathode (-) side of the cassette

- Sponge

- 3 sheets of Filter paper

- Gel

- Membrane (ensure it covers the entire gel)

- 3 sheets of Filter paper

- Sponge

- Anode (+) side of the cassette

- Close the cassette firmly.

Transfer and Post-Transfer Steps

- Transfer Execution: Place the cassette into the transfer tank filled with pre-chilled (4°C) 1X transfer buffer. Ensure the orientation is correct (gel facing cathode, membrane facing anode). The tank should be kept in an ice bath or cold room for the duration of the transfer [4] [34].

- Post-Transfer Processing: After the transfer is complete, you can stain the membrane with Ponceau S to confirm transfer efficiency [36]. Proceed to blocking and antibody incubation. Do not let the membrane dry out at any point.

Optimization Tables for Wet Transfer Conditions

Table 1: Recommended Transfer Parameters by Protein Size

The following table summarizes key parameters for different protein sizes. For HMW proteins, longer times and cooler temperatures are critical [34].

| Protein Size (kDa) | Voltage (V) | Current (mA per gel) | Transfer Time | Key Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 15 (Small) | 30 V | 100-150 mA | 3-4 hours or Overnight | Use 0.2 µm pore membrane; reduce or omit methanol from buffer to prevent over-transfer [34]. |

| 15 - 100 (Medium-Large) | 70-100 V | 200-350 mA | 1-2 hours | Standard conditions with 0.45 µm membranes are typically effective [34]. |

| > 100 (HMW, e.g., Ubiquitinated) | 25-30 V | 100-200 mA | Overnight (12-16 hours) | Add 0.1% SDS to the transfer buffer; reduce methanol to 10-15% to aid protein elution from the gel [34]. |

Table 2: Wet Transfer Buffer Compositions

The composition of your transfer buffer significantly impacts efficiency [36] [4].

| Component | Standard 1X Wet Transfer Buffer | Optimized for HMW Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Tris Base | 25 mM | 25 mM |

| Glycine | 192 mM | 192 mM |

| Methanol | 20% | 10-15% |

| SDS | - | 0.1% |

| Final pH | 8.3 | 8.3 |

Troubleshooting Common Wet Transfer Issues

Problem: Incomplete Transfer of High Molecular Weight Proteins

- Symptoms: Faint or absent bands for your HMW target, even with a strong loading control.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Transfer Time: HMW proteins migrate slowly. Solution: Increase transfer time to overnight at low voltage [34].

- Inefficient Elution from Gel: The gel matrix can trap large proteins. Solution: Modify the transfer buffer by adding 0.1% SDS and reducing methanol to 10-15% to improve protein mobility [34].

- Incorrect Gel Type: Standard Tris-glycine gels can compact HMW proteins. Solution: Use a low-percentage acrylamide gel (e.g., 6-8%) or a Tris-acetate gel, which has a more open matrix better suited for large proteins [3].

Problem: High Background on the Blot

- Symptoms: A uniformly dark or speckled membrane that obscures specific bands.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inadequate Blocking: Solution: Ensure complete coverage with a 5% non-fat dry milk or BSA blocking solution for at least 1 hour at room temperature [36] [37]. Use BSA when detecting phosphoproteins.

- Antibody Concentration Too High: Solution: Titrate your primary and secondary antibodies to find the optimal dilution that maximizes signal and minimizes background [9] [37].

- Insufficient Washing: Solution: Perform three washes of 10 minutes each with TBST (Tris-Buffered Saline with 0.1% Tween-20) after both primary and secondary antibody incubations [36] [37].

Problem: Bands are Distorted or Smiling

- Symptoms: Bands that curve upwards at the edges or appear smeared.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Overheating During Transfer: Solution: Ensure the transfer apparatus is completely submerged in an ice bath or placed in a cold room (4°C). Use a stir bar if available to circulate the buffer [34] [15].

- Air Bubbles in the Sandwich: Solution: Carefully roll out every air bubble when assembling the gel-membrane sandwich [9] [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Considerations for HMW Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| PVDF Membrane | Solid support that binds proteins for antibody probing. | Higher protein binding capacity than nitrocellulose; must be activated in methanol before use [36] [34]. |

| Transfer Buffer | Conducts current and facilitates protein movement. | Critical for HMW proteins: Reduce methanol to 10-15% and add 0.1% SDS to aid transfer [34]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents protein degradation during sample preparation. | Essential for preserving ubiquitinated proteins, which can be rapidly degraded [15]. |

| Ponceau S Stain | Reversible stain for visualizing total protein on membrane. | Quick and effective method to confirm successful transfer and check for air bubbles before antibody steps [36] [9]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent used in sample buffer and transfer buffer. | In transfer buffer, it helps dissociate SDS-protein complexes and improves elution of large proteins from the gel [34]. |

Workflow Diagram: Wet Transfer Setup for HMW Proteins

The following diagram illustrates the assembly of the wet transfer sandwich and apparatus, highlighting key steps for successful transfer of high molecular weight proteins.

In immunoblotting research focused on high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins, effective membrane selection and preparation are critical for success. PVDF membranes are widely preferred for their high protein-binding capacity and mechanical strength, particularly beneficial for detecting large protein complexes. The pretreatment of these membranes with methanol is a essential step that activates the membrane for optimal protein binding and retention. This guide addresses common experimental challenges and provides proven solutions to ensure reliable detection of high molecular weight ubiquitinated species, which are central to understanding numerous cellular regulatory mechanisms [2] [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problem: Poor Transfer Efficiency or High Background

Problem: Incomplete transfer of high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins or excessive background noise on the PVDF membrane.

| Possible Cause | Recommendation | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Membrane Activation | Ensure PVDF membrane is fully immersed in 100% methanol for 15-30 seconds, then transition to transfer buffer. | Methanol treatment renders the hydrophobic PVDF matrix hydrophilic, allowing aqueous buffers to penetrate and facilitating protein entry and binding [39]. |

| Inadequate Blocking | Use 5% BSA or casein-based blocking buffers in TBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Avoid non-fat dry milk with biotin-avidin systems. | BSA and casein effectively cover membrane surfaces without the inherent biotin found in milk, reducing non-specific antibody binding and background [40]. |

| Membrane Autofluorescence | For fluorescent detection, scan an unused PVDF membrane to check autofluorescence. Use low-fluorescence PVDF membranes. | Autofluorescence can create high background, masking specific signals. Low-fluorescence PVDF membranes are engineered to minimize this intrinsic signal [41]. |

| Suboptimal Transfer Conditions | For proteins >100 kDa, extend transfer time, use chilled buffer, or incorporate 0.1% SDS into the transfer buffer. | High molecular weight proteins, like polyubiquitinated conjugates, transfer more slowly out of the gel. Modified conditions enhance their mobility [2]. |

Common Problem: Weak or No Signal for Target Protein

Problem: Despite successful protein transfer, the signal for the ubiquitinated protein of interest is faint or absent.

| Possible Cause | Recommendation | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Over-Fixation after Transfer | If post-transfer fixation is used, limit to brief incubation (5-10 min) with low-concentration formaldehyde. | Excessive cross-linking can mask epitopes, making them inaccessible to antibodies, particularly for complex ubiquitinated proteins [42]. |

| Inefficient Antibody Binding | Perform antibody titration for both primary and secondary antibodies. Validate antibodies for Western blotting. | Antibody concentrations that are too high cause background; too low cause weak signal. Titration finds the optimal balance for detecting low-abundance ubiquitinated conjugates [41]. |

| Target Protein Loss | Ensure membrane remains wet throughout the procedure. Do not allow the activated PVDF membrane to dry out. | A dried PVDF membrane can permanently trap proteins, preventing antibody access. Keeping it wet maintains protein antigenicity [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why is methanol activation absolutely necessary for PVDF membranes?

Methanol activation is crucial because it prepares the hydrophobic PVDF polymer for the aqueous environments used in Western blotting. The methanol treatment serves two primary functions: it solvates the hydrophobic polymer backbone, and it expels the air and preservatives trapped in the pores, replacing them with methanol. This wetting action lowers the interfacial tension, allowing the subsequent aqueous transfer buffer to freely penetrate the membrane matrix. Without this step, the transfer buffer cannot properly access the membrane pores, leading to inefficient protein binding and potentially failed experiments [39].

Can I use ethanol or isopropanol instead of methanol for activation?

While 100% methanol is the universally recommended solvent for PVDF membrane activation due to its optimal effectiveness in wetting the membrane, other alcohols like ethanol or isopropanol can be used in a pinch. However, their efficiency may be lower due to differences in polarity and wetting strength. For consistent and reliable results, especially with high molecular weight proteins that pose greater transfer challenges, sticking with 100% methanol is strongly advised.

How does methanol treatment specifically benefit the detection of high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins?

High molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins, particularly polyubiquitinated conjugates, are large complexes that can be difficult to transfer efficiently from the gel to the membrane [2]. Proper methanol activation ensures the membrane pores are fully open and accessible, creating an unobstructed path for these large complexes to migrate and bind. A fully activated membrane maximizes the binding capacity and retention strength, preventing the loss of these valuable protein species during subsequent washing steps and thereby increasing the sensitivity of their detection.

What is the maximum time a methanol-activated membrane can be stored before use?

For optimal results, an activated PVDF membrane should be used immediately after the methanol treatment and equilibration in transfer buffer. If short-term storage is necessary, the membrane can be kept submerged in cold transfer buffer or deionized water at 4°C for a few hours. However, prolonged storage is not recommended as it can lead to bacterial growth or a gradual decrease in binding performance.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: PVDF Membrane Activation and Western Blot Transfer

This protocol is optimized for the detection of high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins, which exhibit a dramatic increase in molecular weight and require efficient transfer and strong retention [2].

Materials Needed:

- PVDF Membrane

- 100% Methanol (HPLC grade or higher)

- Transfer Buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine or commercial alternatives like Express Transfer Buffer [40])

- Gel and Transfer System

- Forceps

- 2X SDS-PAGE Sample Buffer (with reducing agent like DTT for denaturation [40])

Procedure:

- Cut Membrane: Wearing gloves, use clean forceps to cut a piece of PVDF membrane to the size of your gel.

- Methanol Activation: Place the membrane on the surface of 100% methanol in a clean container. The membrane will quickly change from opaque/white to semi-transparent. Submerge it completely and incubate for 15-30 seconds.

- Equilibration: Carefully decant the methanol. Rinse the membrane briefly with deionized water to remove excess methanol. Submerge the activated membrane in cold transfer buffer and equilibrate for at least 5 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Assemble Transfer Stack: Following your transfer apparatus manual, assemble the "sandwich" in this order (from anode to cathode):

- Anode (+)

- Filter paper (pre-wetted)

- Activated PVDF Membrane

- SDS-PAGE Gel

- Filter paper (pre-wetted)

- Cathode (-)

- Ensure all layers are rolled firmly to exclude air bubbles.

- Electroblotting: Place the cassette in the transfer tank filled with cold transfer buffer. Perform transfer at recommended constant conditions (e.g., 100V for 90 minutes or 30V overnight at 4°C for high molecular weight proteins >100 kDa [2]).

- Post-Transfer Processing: After transfer, disassemble the stack. The membrane can be stained with Ponceau S to verify transfer efficiency [40]. Proceed to blocking and immunodetection.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials for PVDF membrane-based Western blotting, particularly for challenging targets like ubiquitinated proteins.

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| PVDF Membrane | A hydrophobic microporous polymer that binds proteins via hydrophobic and dipole interactions. | Preferred for its high binding capacity and mechanical strength, ideal for sequential staining and reprobing of high molecular weight proteins [40]. |

| 100% Methanol | A polar organic solvent used to activate PVDF membranes. | Solvates the PVDF polymer, making it hydrophilic and allowing aqueous buffers to permeate the pores for effective protein binding [39]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) - Fraction V | A high-purity protein used as a primary component in blocking buffers. | Preferred over non-fat dry milk for phospho-specific antibodies and biotin-avidin detection systems, as it lacks inherent biotin [40]. |

| Casein-Based Blocking Buffer | A blocking agent derived from milk protein. | Provides low background and is highly recommended for applications using biotin-avidin complexes due to its effective suppression of non-specific binding [40]. |

| Fish Gelatin Blocking Buffer | A blocking agent derived from fish skin gelatin. | Less likely to cross-react with antibodies of mammalian origin, making it an excellent choice for reducing background with mammalian primary antibodies [40]. |

| Prestained Protein Marker | A mixture of proteins of known size, conjugated to visible dyes. | Allows real-time tracking of electrophoresis and immediate verification of protein transfer efficiency after blotting [40]. |

| Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate | A reagent that produces light upon reaction with Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) enzyme. | Offers high sensitivity for detecting low-abundance proteins. Ultra-sensitive substrates (e.g., FemtoMax) are recommended for weak signals [40]. |

Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagrams

PVDF Membrane Activation Workflow

High MW Ubiquitinated Protein Transfer Troubleshooting

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for experiments involving tagged ubiquitin systems, ubiquitin antibodies (Ub antibodies), and ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs). The content is framed within the broader thesis of improving the transfer and detection of high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins in immunoblotting research, addressing common challenges faced by researchers in protein analysis and drug development.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: Why is the transfer efficiency of high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins (>150 kDa) low in my Western blots?