Optimizing NEM and IAA Concentration for Deubiquitylase (DUB) Inhibition: A Guide for Experimental Design and Validation

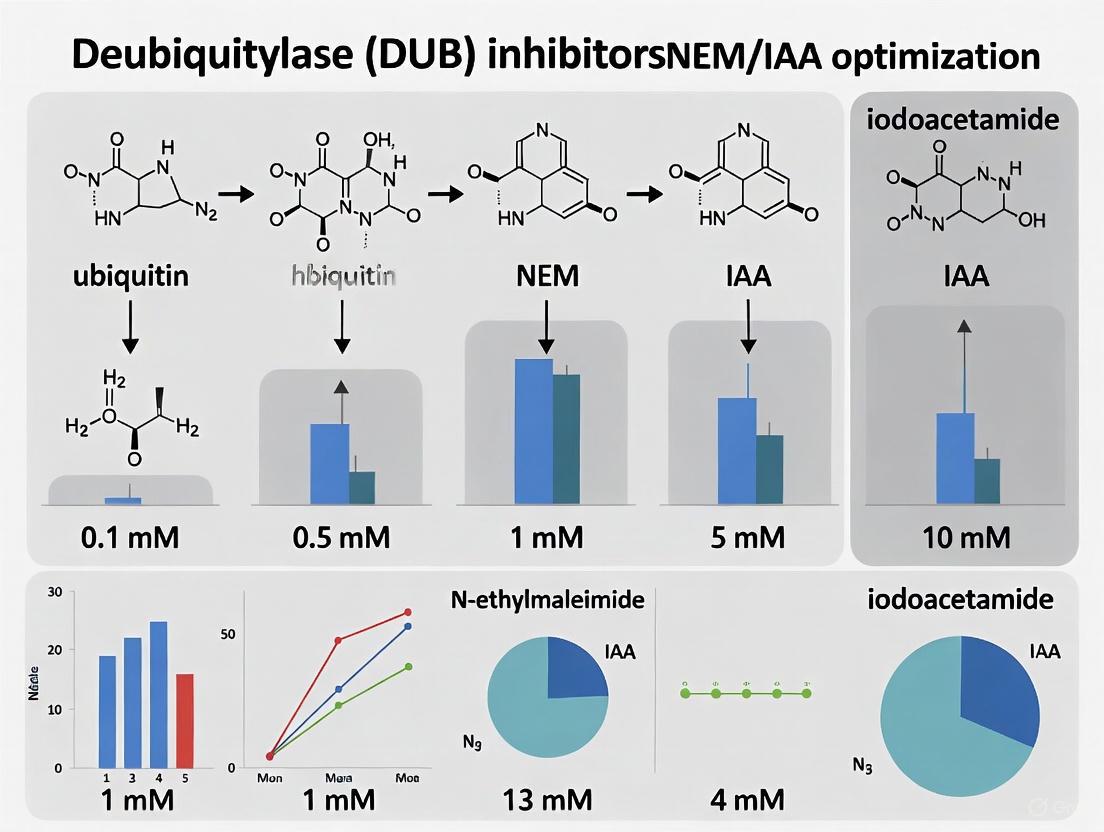

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the use and optimization of the deubiquitylase (DUB) inhibitors N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) and Iodoacetamide (IAA).

Optimizing NEM and IAA Concentration for Deubiquitylase (DUB) Inhibition: A Guide for Experimental Design and Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the use and optimization of the deubiquitylase (DUB) inhibitors N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) and Iodoacetamide (IAA). Covering foundational mechanisms to advanced validation techniques, we detail how these cysteine protease inhibitors are crucial for stabilizing the cellular ubiquitome by preventing deubiquitination. The content explores methodological applications in protein isolation and functional assays, tackles troubleshooting for concentration optimization and artifact mitigation, and outlines contemporary validation strategies using activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) and selectivity panels to ensure experimental rigor in DUB research.

Understanding DUB Inhibition: The Foundational Roles of NEM and IAA

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a crucial regulatory pathway for intracellular protein degradation and homeostasis, where the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to protein substrates signals for their proteasomal degradation or alters their function, localization, and activity [1] [2]. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) perform the reverse reaction, countering the activity of ubiquitin conjugases and ligases by selectively removing ubiquitin from substrate proteins, thereby recycling ubiquitin and regulating diverse cellular processes [3] [1]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, which are classified into two main classes based on their catalytic mechanisms: cysteine proteases and metalloproteases [2] [4].

Cysteine protease DUBs represent the largest class of deubiquitinating enzymes and are characterized by a catalytic mechanism that relies on a nucleophilic cysteine residue in their active site [3] [5]. This class encompasses six distinct families: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Machado-Josephin domain proteases (MJDs), motif interacting with ubiquitin-containing novel DUB family (MINDY), and zinc finger with UFM1-specific peptidase domain protein (ZUFSP) [2] [5]. These enzymes are highly specific, recognizing particular ubiquitin chain linkages and protein substrates, and their activity is tightly regulated through various mechanisms including protein-protein interactions, post-translational modifications, subcellular localization, and oxidative stress [3]. The cysteine protease DUBs have garnered significant research interest due to their implications in human diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [3] [6] [5].

Catalytic Mechanism and Biochemical Action

The catalytic mechanism of cysteine protease DUBs centers on a conserved catalytic triad typically composed of cysteine, histidine, and aspartate or asparagine residues [5]. The deubiquitination process follows a coordinated multi-step mechanism that ensures precise recognition and cleavage of ubiquitin from substrate proteins.

Structural Features and Ubiquitin Recognition

Cysteine protease DUBs contain specialized ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) that facilitate recognition of specific ubiquitin chain linkages and substrates [2]. Common UBDs include ubiquitin-associated domains (UBA), ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIM), and zinc finger domains, which enable DUBs to discriminate between the various ubiquitin chain architectures and topologies [2]. For instance, the OTU family DUB OTUD1 specifically hydrolyzes Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains, with its UIM domain being indispensable for this linkage specificity [2].

Steps in the Catalytic Cycle

The enzymatic cleavage of ubiquitin from substrates proceeds through a conserved pathway:

- Ubiquitin Binding: The DUB recognizes and binds the ubiquitin moiety through its ubiquitin-binding domains, positioning the scissile isopeptide bond near the active site.

- Nucleophilic Attack: The catalytic cysteine residue performs a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the isopeptide bond linking ubiquitin to the substrate lysine residue.

- Tetrahedral Intermediate Formation: A transient tetrahedral oxyanion intermediate is formed, stabilized by hydrogen bonding with surrounding residues.

- Bond Cleavage and Acyl-Enzyme Complex: The isopeptide bond is cleaved, releasing the deubiquitinated substrate and forming a thioester intermediate between the catalytic cysteine and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin.

- Nucleophilic Attack and Ubiquitin Release: A water molecule performs a nucleophilic attack on the thioester bond, hydrolyzing it and releasing free ubiquitin while regenerating the active enzyme.

The following diagram illustrates this catalytic mechanism:

Figure 1: Catalytic Mechanism of Cysteine Protease DUBs

Major Families of Cysteine Protease DUBs and Their Characteristics

Cysteine protease DUBs are categorized into distinct families based on sequence and structural similarities. The table below summarizes the key features, specificities, and representative members of each family:

Table 1: Major Families of Cysteine Protease DUBs

| Family | Representative Members | Known Ubiquitin Linkage Specificity | Key Structural Features | Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP (Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases) | USP5, USP7, USP14, USP21, USP22, USP28, USP33, USP34 | Varied; family members show diverse specificities | Largest family; catalytic domain with Cys and His boxes; multiple ubiquitin-binding domains | Cell cycle regulation, transcription, DNA repair, Wnt/β-catenin signaling [2] [6] |

| OTU (Ovarian Tumor Proteases) | A20, OTUD1 | K63 (OTUD1) | OTU domain; often contains additional regulatory domains | NF-κB signaling, immune regulation, apoptosis [3] [2] |

| UCH (Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolases) | UCH37, BAP1, UCH-L1 | Prefers small adducts and ubiquitin C-terminal esters | Compact structure with crossover loop | Neuronal function, chromatin regulation, cancer [2] [6] |

| MJD (Machado-Josephin Domain Proteases) | ATXN3, ATXN3L | K48, K63 | Catalytic Josephin domain; contains ubiquitin-interaction motifs | Protein homeostasis, ER-associated degradation, transcription [3] |

| MINDY (Motif Interacting with Ubiquitin-Containing Novel DUB Family) | N/A | Prefers K48-linked ubiquitin chains | Distinct from other families; specific for degradation signals | Proteasomal degradation regulation [2] |

| ZUFSP (Zinc Finger with UFM1-Specific Peptidase Domain Protein) | N/A | Specific for K63-linked and linear ubiquitin chains | Zinc finger domain and protease domain | DNA damage response, genome integrity [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Cysteine Protease DUBs

Ubiquitinome Profiling to Identify DUB Substrates

Principle: This protocol uses mass spectrometry-based proteomics to identify endogenous ubiquitination sites and monitor changes in response to DUB inhibition, enabling the mapping of DUB-regulated substrates and pathways [4].

Reagents and Solutions:

- Cell culture medium appropriate for your cell line (e.g., DMEM for U2OS cells)

- DUB inhibitor: PR619 (cysteine protease inhibitor), dissolved in DMSO

- Proteasome inhibitor: MG132, dissolved in DMSO

- Ub E1 inhibitor: TAK243, dissolved in DMSO (negative control)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), ice-cold

- Lysis buffer: 6 M Guanidine-HCl, 100 mM Na₂HPO₄/NaH₂PO₄, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM imidazole, pH 8.0

- Ni-NTA beads for His-tagged ubiquitin pull-down or UbiSite antibody for endogenous ubiquitin site enrichment

- Wash buffer 1: 8 M Urea, 100 mM Na₂HPO₄/NaH₂PO₄, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM imidazole, pH 8.0

- Wash buffer 2: 8 M Urea, 100 mM Na₂HPO₄/NaH₂PO₄, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM imidazole, pH 6.3

- Elution buffer: 200 mM Imidazole, 0.15 M Tris-HCl, 30% glycerol, 0.72 M β-mercaptoethanol, 5% SDS, pH 6.7

- Salkowski reagent for IAA quantification (optional: 12 g FeCl₃ in 300 mL distilled water mixed with 300 mL 35% perchloric acid)

Procedure:

Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Culture U2OS cells (or your cell line of interest) to 70-80% confluence.

- Treat cells with:

- Condition A: DMSO vehicle control (3 h)

- Condition B: 50 μM PR619 (3 h)

- Condition C: 10 μM MG132 (3 h)

- Condition D: 1 μM TAK243 (3 h)

- Include biological replicates for each condition (n ≥ 3).

Cell Harvest and Lysis:

- Wash cells twice with ice-cold PBS.

- Scrape cells in PBS and pellet by centrifugation (500 × g, 5 min, 4°C).

- Lyse cell pellets in lysis buffer (use 1 mL per 10⁷ cells).

- Sonicate samples to reduce viscosity and clarify by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C).

Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment:

- For His-tagged ubiquitin systems:

- Incubate lysate with Ni-NTA beads (2 h, 4°C with rotation).

- Wash sequentially with wash buffer 1, wash buffer 2, and PBS.

- Elute ubiquitinated proteins with elution buffer.

- For endogenous ubiquitin site mapping:

- Use UbiSite antibody for immunoprecipitation following manufacturer's protocol.

- Digest enriched proteins with trypsin/Lys-C mixture.

- For His-tagged ubiquitin systems:

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Desalt and concentrate peptides using C18 StageTips.

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS on a high-resolution mass spectrometer.

- Identify ubiquitination sites using database search algorithms (e.g., MaxQuant) with diGly remnant (GG; 114.0429 Da) as variable modification.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize peptide intensities across samples.

- Perform statistical analysis (Student's t-test, FDR correction) to identify significantly changed ubiquitination sites.

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis using databases like KEGG or GO.

The experimental workflow for ubiquitinome profiling is illustrated below:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitinome Profiling

In Vitro DUB Activity Assay with IAA Concentration Optimization

Principle: This protocol measures cysteine protease DUB activity in vitro using ubiquitin-based substrates, with optimization of indole acetic acid (IAA) concentrations for specific reaction conditions.

Reagents and Solutions:

- Recombinant cysteine protease DUB (USP, OTU, UCH, MJD, MINDY, or ZUFSP family member)

- Ubiquitin-AMC (7-amido-4-methylcoumarin) or ubiquitin-rhodamine 110 substrate

- Assay buffer: 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 5 mM DTT, pH 7.5

- Indole acetic acid (IAA) stock solution: 100 mM in DMSO

- DUB inhibitor control: PR619 (10 mM in DMSO)

- Stop solution: 500 mM IAA in assay buffer

Procedure:

IAA Concentration Optimization:

- Prepare a dilution series of IAA in assay buffer (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 μM).

- Pre-incubate recombinant DUB (10 nM) with different IAA concentrations (15 min, 25°C).

- Initiate reaction by adding ubiquitin-AMC substrate (100 nM final concentration).

- Monitor fluorescence (excitation 355 nm, emission 460 nm) every minute for 30 min.

- Plot initial velocity versus IAA concentration to determine optimal non-inhibitory concentration.

DUB Activity Measurement:

- In black 96-well plates, mix:

- 50 μL assay buffer

- 10 μL DUB enzyme (final concentration 1-10 nM)

- 10 μL IAA at optimized concentration

- Pre-incubate (15 min, 25°C).

- Add 30 μL ubiquitin-AMC substrate (100 nM final).

- Immediately measure fluorescence kinetics (30 min, 25°C).

- In black 96-well plates, mix:

Data Analysis:

- Calculate initial velocities from linear portion of progress curves.

- Determine kinetic parameters (Kₘ, Vₘₐₓ) by varying substrate concentration.

- For inhibitor studies, include PR619 control and calculate IC₅₀ values.

Table 2: Example IAA Optimization Results for Different DUB Families

| DUB Family | Optimal IAA Concentration (μM) | Relative Activity (%) | Inhibition at High IAA (500 μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP | 50-100 | 95-100% | >90% |

| OTU | 25-50 | 90-95% | >85% |

| UCH | 10-25 | 85-90% | >80% |

| MJD | 50-75 | 92-98% | >88% |

| MINDY | 75-100 | 88-94% | >82% |

| ZUFSP | 25-50 | 91-96% | >86% |

Regulatory Mechanisms and Physiological Roles

Cysteine protease DUBs are subject to multiple layers of regulation that ensure precise spatial and temporal control of their activity. Understanding these regulatory mechanisms is essential for comprehending their physiological functions and targeting them therapeutically.

Redox Regulation and Oxidative Stress Sensitivity

The catalytic cysteine residue in cysteine protease DUBs is highly sensitive to oxidative modification by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [3]. Under oxidative stress conditions, ROS directly modify the catalytic cysteine, leading to reversible oxidation and transient inhibition of DUB activity. This redox regulation creates a link between cellular oxidative status and ubiquitin signaling, allowing DUBs to function as sensors of oxidative stress and modulate pathways accordingly [3].

Regulation Through Protein-Protein Interactions and Complex Formation

Many cysteine protease DUBs require binding partners for full enzymatic activity or substrate specificity. For instance, USP1 forms a complex with UAF1, which greatly enhances its catalytic activity [5]. Similarly, USP7 (HAUSP) contains adjacent ubiquitin-like domains that are indispensable for achieving complete deubiquitinating activity [2]. These regulatory interactions ensure that DUB activity is directed toward appropriate substrates in specific cellular contexts.

Physiological Functions in Cellular Signaling

Cysteine protease DUBs regulate numerous critical cellular pathways:

- Wnt/β-catenin signaling: USP5, USP28, and UCH37 regulate this pathway by stabilizing key transcription factors like FOXM1 and Tcf7 [2] [6].

- NF-κB pathway: A20 (TNFAIP3) and CYLD negatively regulate NF-κB activation by deubiquitinating signaling components [3] [2].

- DNA damage response: USP1 regulates DNA damage repair by deubiquitinating PCNA and other repair factors [5].

- Cell cycle progression: Multiple USP family members control cell cycle regulators, ensuring proper cycle progression and genomic stability [2] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Cysteine Protease DUB Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Example Usage | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR619 | Pan-cysteine protease DUB inhibitor | Mechanism studies; ubiquitinome profiling [4] | Inhibits all cysteine protease DUB families; not selective for individual DUBs |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Cysteine alkylating agent; DUB inhibitor | Sample preparation to preserve ubiquitin conjugates | Irreversible modification; use in lysis buffers to prevent deubiquitination during processing |

| Indole Acetic Acid (IAA) | Redox modulator; concentration-dependent DUB effector | Optimization of DUB activity assays; study of redox regulation | Concentration-critical; low concentrations may enhance, high concentrations inhibit |

| Ubiquitin-AMC | Fluorogenic DUB substrate | High-throughput screening; kinetic studies | Continuous monitoring of DUB activity; sensitive to environmental conditions |

| TAK243 | Ubiquitin E1 inhibitor | Negative control in ubiquitination studies; blocks all ubiquitination | Complete shutdown of ubiquitin system; cytotoxic with prolonged treatment |

| MG132 | Proteasome inhibitor | Study of proteasome-dependent versus -independent DUB functions | Accumulates ubiquitinated substrates; may induce stress responses |

| His10-Ubiquitin | Affinity-tagged ubiquitin | Purification of ubiquitinated proteins for proteomics | Enables selective enrichment; may affect normal ubiquitin dynamics |

| UbiSite Antibody | Endogenous ubiquitin site antibody | Site-specific ubiquitinomics without overexpression | Specific for ubiquitin (not NEDD8 or ISG15); identifies exact modification sites |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Targeting

The critical roles of cysteine protease DUBs in human diseases have made them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention. Several DUB inhibitors are currently in various stages of development, with promising applications in cancer therapy and other diseases.

DUB Inhibitors in Clinical Development

The emerging pipeline for DUB inhibitors features several promising candidates:

- USP1 inhibitors: KSQ-4279 (KSQ Therapeutics/Roche) for cancer therapy [7] [5]

- USP7 inhibitors: Multiple candidates in preclinical development for cancer [5]

- USP30 inhibitors: MTX325 (Mission Therapeutics) for Parkinson's disease [7]

- USP14 inhibitors: Candidates for cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [8]

Therapeutic Applications in Pancreatic Cancer

Cysteine protease DUBs play significant roles in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) pathogenesis:

- USP28 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits apoptosis by stabilizing FOXM1 [6].

- USP21 maintains stemness of PDAC cells by stabilizing TCF7 and activates mTOR signaling [6].

- USP5 regulates DNA damage response, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis to promote PDAC tumor formation [6].

- USP9X demonstrates context-dependent roles, acting as both oncogene and tumor suppressor in PDAC [6].

The development of selective DUB inhibitors represents a promising therapeutic strategy for targeting specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells while potentially minimizing side effects associated with broader proteasome inhibition [5].

Cysteine protease DUBs represent a diverse and critically important class of enzymes that regulate virtually all cellular processes through their control of the ubiquitin code. Their conserved catalytic mechanism centered on a nucleophilic cysteine residue, combined with family-specific structural features and regulatory domains, enables precise substrate recognition and cleavage specificity. The experimental approaches outlined in this application note, particularly ubiquitinome profiling and optimized activity assays, provide powerful tools for investigating DUB function and mechanism.

The growing recognition of DUBs as therapeutic targets, evidenced by an expanding pipeline of selective inhibitors, highlights the translational importance of fundamental research in this field. As our understanding of DUB biology continues to advance, particularly through structural insights and proteomic approaches, new opportunities will emerge for targeting these enzymes in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other human diseases. The integration of DUB inhibitors with other therapeutic modalities, including PROTACs and combination therapies, represents a particularly promising direction for future drug development.

Chemical Mechanism of Action

N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) functions as a potent covalent cysteine modifier through a specific Michael addition reaction. Its mechanism centers on the high electrophilicity of the carbon-carbon double bond within its maleimide ring structure. This double bond is highly susceptible to nucleophilic attack by the thiolate anion (S⁻) of a deprotonated cysteine residue.

The reaction proceeds via a thioether linkage, resulting in the stable addition of the NEM molecule across the double bond and the formation of a covalent adduct with the cysteine thiol. This modification effectively blocks the native function of the cysteine residue, which is critical for understanding its role as an enzyme inhibitor, particularly for cysteine-dependent deubiquitinases (DUBs). While this alkylation is typically considered irreversible under physiological conditions, some studies on metallothionein have noted a degree of reversibility under specific non-physiological conditions, such as in the presence of a large excess of competing thiols like 2-mercaptoethanol [9].

Reaction Kinetics and Specificity

The alkylation of cysteine residues by NEM is characterized by rapid reaction kinetics. Specificity for cysteine is derived from the superior nucleophilicity of the thiolate anion compared to other functional groups in proteins, such as primary amines (e.g., lysine) or hydroxyl groups.

However, non-specific alkylation can occur at other nucleophilic sites if reaction conditions are not carefully controlled. Key factors influencing both the rate of cysteine alkylation and specificity include pH, NEM concentration, and reaction time [10].

- pH Dependence: The reaction rate increases with pH. A higher pH favors the deprotonated, more nucleophilic thiolate form of cysteine, accelerating alkylation. For specific cysteine modification, it is recommended to restrict the pH below neutral [10].

- Concentration & Time: Maximal and specific cysteine alkylation in complex systems like tissue homogenates can be achieved with 40 mM NEM within 1 minute. Lower concentrations (e.g., below 10 mM) also provide rapid and specific alkylation, while longer reaction times or higher concentrations can lead to increased modification of histidine and lysine residues [10].

Table 1: Optimization of NEM Reaction Conditions for Specific Cysteine Alkylation

| Parameter | Recommended Condition for Specificity | Effect of Suboptimal Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Below neutral (e.g., pH 7.0 or lower) | Increased reaction rate but potential for mis-alkylation at other nucleophiles. |

| Concentration | < 10 mM (for simple systems); 40 mM (for complex homogenates) | Concentrations > 10 mM can lead to mis-alkylation at Lys and His residues [10]. |

| Reaction Time | < 5 minutes; as little as 1 minute for homogenates | Longer incubation times increase non-specific alkylation without benefit [10]. |

| Temperature | Room Temperature or 30°C (commonly used) | Higher temperatures may accelerate non-specific reactions. |

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Inhibition of Deubiquitinases (DUBs) for Functional Studies

NEM is a broad-spectrum, cysteine-reactive DUB inhibitor used to study ubiquitin signaling.

- Principle: Many DUBs are cysteine proteases. NEM alkylates the catalytic cysteine, irreversibly inhibiting enzyme activity.

- IC₅₀ Value: The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) of NEM for the DUB AMSH is reported to be 16.2 ± 3.2 µM [11].

- Reagent Setup:

- NEM Stock Solution: Prepare a 100-500 mM solution in DMSO or ethanol. Store aliquots at -20°C.

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 25 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT*.

- Note: DTT is a reducing agent and will compete with the enzyme for NEM. It must be included in the reaction buffer *before NEM addition to maintain protein reduction, but the inhibitory reaction itself is performed by pre-incubating the DUB with NEM in the absence of DTT (see procedure below).

- Procedure:

- Pre-incubation: Dilute the DUB (e.g., AMSH at 125 nM) in reaction buffer without DTT. Add NEM (0.8 µM – 500 µM for a dose-response) and incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature [11].

- Quenching: After alkylation, residual NEM can be quenched by adding a 5-10 fold molar excess of DTT compared to the NEM concentration.

- Activity Assay: Initiate the deubiquitination reaction by adding the ubiquitin substrate (e.g., 500 nM Lys63-linked diubiquitin FRET probe) and the necessary cofactors, including DTT, to the quenched mixture. Incubate for 90 minutes at 30°C and measure remaining activity [11].

Protocol 2: Prevention of Artificial Thiol Oxidation in Redox Biology

NEM is critical in sample preparation for accurate measurement of glutathione (GSH) and glutathione disulfide (GSSG) ratios, a key metric of cellular oxidative stress [12].

- Principle: During cell lysis and acidification, GSH can artificially oxidize to GSSG, drastically skewing the GSH/GSSG ratio. NEM rapidly alkylates and "locks" GSH in its reduced state, preventing this artifact [12] [13].

- Reagent Setup:

- NEM Solution: Prepare a fresh, aqueous solution of NEM. A concentration of 20 mM NEM is commonly used in lysis buffers [14].

- Lysis/Wash Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 20 mM NEM and 5 mM Iodoacetate (IAA). IAA acts as an additional alkylating agent to ensure complete thiol blocking [14].

- Procedure:

- Harvesting: Harvest cells (e.g., hepatocytes) at the desired time point.

- Wash: Immediately wash the cell pellet with ice-cold PBS containing 20 mM NEM and 5 mM IAA [14].

- Lysis: Lyse the washed cell pellet in a denaturing buffer (e.g., containing SDS) that also includes 20 mM NEM. Maintain denaturing conditions to inactivate endogenous enzymes and eliminate non-covalent interactions [14].

- Analysis: Proceed with LC-MS/MS or enzymatic assays for GSH and GSSG quantification [13].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for NEM-based Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Usage & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Irreversible cysteine alkylator; inhibits cysteine-dependent enzymes, blocks thiol oxidation. | Use in mM concentrations (e.g., 5-40 mM) for alkylation; µM range for DUB inhibition [10] [11]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent; breaks disulfide bonds, competes with NEM. | Quench NEM reactions after alkylation is complete. Do not include during NEM incubation [11]. |

| Iodoacetamide (IAA) | Alternative alkylating agent; modifies cysteine residues. | Often compared to NEM; can be used in conjunction for complete thiol blocking (e.g., 5 mM) [14]. |

| HEPES Buffer | Biological buffer for maintaining pH during reactions. | Used at pH 7.0-7.5 for DUB activity assays [11]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Organic solvent for dissolving and storing NEM stock. | Final concentration in assays should be tolerated (e.g., <5%) [11]. |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | In vitro model for studying drug metabolism and oxidative stress. | Used to validate GSH/GSSG ratio changes under oxidative stress [13]. |

| FRET-based Diubiquitin Probes | Fluorescent substrates for monitoring DUB enzyme activity. | Lys63-linked probes are specific for DUBs like AMSH [11]. |

For researchers incorporating NEM into their experimental workflows, particularly in the context of DUB inhibition and redox biology, the following points are paramount:

- Specificity is Condition-Dependent: NEM's value as a specific cysteine alkylator is contingent on optimized reaction conditions. Low pH (<7), short incubation times (<5 min), and moderate concentrations (<10-40 mM) are crucial to minimize mis-alkylation of histidine and lysine residues [10].

- Handling of Reductants is Key: The inhibitory reaction with NEM must be performed in the absence of thiol-based reducing agents like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol, as these will readily scavenge NEM. These agents should be added afterwards to quench the reaction [11].

- Essential for Redox-Accurate Data: The use of NEM is non-negotiable for the accurate determination of GSH/GSSG ratios. Without immediate thiol blockade during sample preparation, massive artifactual oxidation occurs, rendering data unreliable [12].

In the study of deubiquitylases (DUBs) and other cysteine-dependent enzymes, precise inhibition through thiol-reactive alkylating agents is a cornerstone technique for elucidating enzymatic mechanisms and cellular functions. Iodoacetamide (IAA) and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) represent two widely employed irreversible inhibitors that selectively target cysteine residues within enzyme active sites. These compounds function by forming stable covalent adducts with the nucleophilic thiolate anion of catalytic cysteine residues, thereby permanently ablating enzymatic activity. Within the specific context of DUB inhibitor research, optimization of IAA and NEM concentration parameters is critical for achieving selective inhibition while minimizing off-target effects. This application note provides a detailed comparison of IAA and NEM functionalities, reaction kinetics, and biochemical applications, supported by structured quantitative data and optimized experimental protocols for DUB research.

Chemical Properties and Reaction Mechanisms

Iodoacetamide (IAA): Structure and Reactivity

Iodoacetamide (IAA), with the chemical formula ICH₂CONH₂ and a molecular weight of 184.96 g/mol, is a white crystalline solid that appears yellow when iodine is present [15]. It is highly soluble in polar solvents such as water (0.5 M or ~92 g/L at 20°C), ethanol, and DMSO [16]. IAA functions primarily as an alkylating agent, reacting with thiol groups via an S_N2 nucleophilic substitution mechanism. The electrophilic iodomethyl group undergoes attack by the sulfur atom of a cysteine thiolate anion, resulting in a stable S-carboxyamidomethyl thioether derivative and the release of hydrogen iodide [16]. This reaction is most efficient at neutral to slightly alkaline pH, which favors the deprotonated, more nucleophilic thiolate form (RS⁻) of cysteine residues [15].

N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM): Structure and Reactivity

N-Ethylmaleimide (C₆H₇NO₂, MW 125.13 g/mol) operates through a distinct Michael addition mechanism. Its maleimide ring contains an electron-deficient carbon-carbon double bond that undergoes nucleophilic attack by cysteine thiols, resulting in a stable thioether adduct without leaving group elimination [17]. This reaction proceeds effectively across a broader pH range, including mildly acidic conditions (pH ~6.0), due to the inherent electrophilicity of the maleimide double bond [17] [18].

Table 1: Fundamental Chemical Properties of IAA and NEM

| Property | Iodoacetamide (IAA) | N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | C₂H₄INO | C₆H₇NO₂ |

| Molecular Weight | 184.96 g/mol | 125.13 g/mol |

| Reactive Group | Iodomethyl (alkylating agent) | Maleimide ring (Michael acceptor) |

| Primary Mechanism | S_N2 nucleophilic substitution | Michael addition |

| Reaction Product | S-carboxyamidomethyl derivative | Thioether succinimide derivative |

| Optimal Reaction pH | Neutral to alkaline (pH 7.0-8.5) | Broad range, including acidic (pH 6.0-8.0) |

| Solubility in Water | High (0.5 M, ~92 g/L) | Moderate to High |

| Leaving Group | Iodide (I⁻) | None |

Functional Comparison in Biochemical Systems

Specificity and Efficiency for Thiol Modification

Both IAA and NEM demonstrate high specificity for cysteine thiol modification, yet exhibit crucial differences in reaction kinetics and contextual efficiency. Comparative studies on red blood cell membranes revealed differential reactivity toward membrane protein sulfhydryl groups, with NEM treatment stimulating chloride-dependent potassium transport in low potassium cells at pH 6.0, an effect abolished by prior IAA exposure [17]. This indicates that NEM and IAA may target distinct subsets of cysteine residues based on local chemical microenvironments.

A systematic analysis of reagent effectiveness for alkylating protein thiols found NEM superior in several operational parameters: it required significantly less reagent (125-fold molar excess versus 1000-fold for IAA), achieved complete modification faster (4 minutes versus 4 hours), and demonstrated greater efficacy at lower pH values (pH 4.3) [18]. This enhanced reactivity profile makes NEM particularly valuable for experiments requiring rapid thiol quenching or conducted under mildly acidic conditions.

Differential Effects on Glycolysis and Glutathione Metabolism

Notable functional differences emerge in cellular metabolism studies. Research on astrocyte cultures demonstrated that iodoacetate (IA, a carboxylate analog of IAA) and IAA differentially affect glycolysis and glutathione metabolism [19]. While both compounds inhibit glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) – a glycolytic enzyme with an active-site cysteine – their relative potencies diverge significantly. IA was approximately ten times more efficient than IAA at inhibiting lactate production (half-maximal effect below 100 μM for IA versus ~1 mM for IAA) [19]. Conversely, IAA depleted cellular glutathione (GSH) content more efficiently than IA (half-maximal effects at ~10 μM for IAA versus ~100 μM for IA) [19]. These findings highlight critical distinctions in biological activity that inform reagent selection for metabolic studies.

Table 2: Functional Comparison in Biological Systems

| Parameter | Iodoacetamide (IAA) | N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Thiol Reactivity | Moderate; enhanced at alkaline pH | High; effective across broad pH range |

| Optimal Alkylation pH | 7.0-8.5 | 6.0-8.0 |

| Time for Complete Reaction | 1-4 hours (at 1 mM) | <5 minutes (at 1-5 mM) |

| Molar Excess Required | High (up to 1000:1 protein SH:reagent) | Low (125:1 protein SH:reagent) |

| GAPDH Inhibition Potency | Moderate (IC₅₀ ~1 mM for lactate inhibition) | Not specifically reported |

| GSH Depletion Efficiency | High (EC₅₀ ~10 μM) | Not specifically reported |

| Membrane Transport Effects | Inhibits NEM-stimulated K+ transport | Stimulates Cl−-dependent K+ transport in LK RBC |

| Proteomic Application | Peptide mapping, cysteine blocking in MS | Thiol trapping, redox proteomics |

Application in Deubiquitylase (DUB) Inhibition and Proteomics

DUB Inhibition Mechanisms

IAA functions as an effective DUB inhibitor through covalent alkylation of the catalytic cysteine residue essential for deubiquitinating enzyme activity [15]. This modification irreversibly inactivates the enzyme by blocking the nucleophilic cysteine required for cleaving ubiquitin chains. In proteomic studies, IAA is extensively utilized during sample preparation to alkylate reduced cysteine thiols, thereby preventing disulfide bond formation and ensuring accurate protein identification and quantification in mass spectrometry analyses [15] [20]. The ICAT (Isotope Coded Affinity Tag) methodology pioneered by Aebersold and colleagues employs a biotin-conjugated iodoacetamide derivative for quantitative proteomics, enabling isolation and relative quantification of cysteine-containing peptides [20].

Concentration Optimization for DUB Research

Optimizing inhibitor concentration is paramount for specific DUB inhibition while minimizing non-specific protein alkylation. For IAA, standard concentrations range from 1-10 mM in proteomic workflows, with incubation times of 30-60 minutes in darkness at room temperature [20] [16]. NEM is typically used at 1-5 mM concentrations, with significantly shorter incubation times (10-30 minutes) sufficient for complete thiol modification [17] [18]. Recent research highlights the critical importance of concentration optimization, as excessive IAA concentrations can lead to substantial unspecific side reactions, including methionine alkylation, which complicates mass spectrometric analysis [15].

DUB Inhibition by Thiol-Reactive Agents

Experimental Protocols for Concentration Optimization

Protocol 1: Determining Minimal Effective Concentration for DUB Inhibition

Objective: Establish the minimum IAA/NEM concentration required for complete DUB inhibition while preserving protein integrity for downstream analysis.

Materials:

- Purified DUB enzyme or DUB-containing cell lysate

- IAA stock solution (1 M in water, prepared fresh)

- NEM stock solution (500 mM in ethanol or DMSO)

- Reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5-8.0 for IAA; pH 6.5-7.5 for NEM)

- Ubiquitin-AMC or ubiquitin-rhodamine substrate

- Fluorescence plate reader

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of IAA (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10 mM) and NEM (0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5 mM) in reaction buffer.

- Incubate DUB enzyme (10-100 nM) with each inhibitor concentration for 30 minutes at 25°C in darkness.

- Add ubiquitin substrate (100-500 nM) and monitor fluorescence (excitation/emission: 355/460 nm for AMC; 485/535 nm for rhodamine) for 30-60 minutes.

- Calculate residual DUB activity relative to untreated control.

- Identify minimal concentration yielding >95% inhibition for subsequent experiments.

Critical Parameters:

- Maintain consistent protein concentration across conditions

- Protect IAA reactions from light to prevent iodine liberation

- Include vehicle-only controls to exclude solvent effects

- Verify pH stability, especially for IAA at higher concentrations

Protocol 2: Proteomic Workflow for Cysteine Alkylation in DUB Studies

Objective: Optimize IAA and NEM alkylation conditions for mass spectrometry-based identification of DUB active sites.

Materials:

- DUB-containing protein samples

- Lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1% SDS, pH 8.0)

- Reducing agent (100 mM DTT or 50 mM TCEP)

- Alkylation reagents: IAA (1 M fresh stock) or NEM (500 mM stock)

- Protein purification columns (e.g., Zeba Spin Desalting Columns)

- Trypsin/Lys-C protease mixture

- Mass spectrometry-compatible buffer (50 mM ammonium bicarbonate)

Procedure:

- Extract proteins using lysis buffer with protease inhibitors.

- Reduce disulfide bonds with 5 mM DTT or 10 mM TCEP for 30 minutes at 55°C.

- Divide samples for parallel IAA and NEM treatment:

- IAA condition: Add IAA to 10-15 mM final concentration, incubate 30 minutes at 25°C in darkness

- NEM condition: Add NEM to 5-10 mM final concentration, incubate 15 minutes at 25°C

- Terminate alkylation by adding 10 mM DTT or desalting.

- Digest with trypsin/Lys-C (1:25-1:50 enzyme:protein) overnight at 37°C.

- Analyze peptides by LC-MS/MS, monitoring for cysteine alkylation signatures (+57.0215 Da for carbamidomethylation with IAA; +125.0477 Da for N-ethylsuccinimide with NEM).

Optimization Notes:

- For complex samples, test IAA concentrations from 5-40 mM and NEM from 2-20 mM

- Higher IAA concentrations may be needed for complete alkylation but risk methionine modification

- NEM alkylation efficiency decreases above pH 8.0 due to maleimide ring hydrolysis

- Include controls without alkylation to assess spontaneous disulfide reformation

Proteomic Workflow for Cysteine Alkylation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DUB Inhibition Studies

| Reagent | Typical Concentration | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Iodoacetamide (IAA) | 1-40 mM (10-15 mM typical) | Alkylates cysteine thiols; optimal at pH 7.0-8.5; prepare fresh aqueous solution protected from light. |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | 1-20 mM (5-10 mM typical) | Alkylates cysteine thiols via Michael addition; effective at pH 6.0-8.0; stable in DMSO/ethanol stocks. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | 1-100 mM (5-10 mM typical) | Reduces disulfide bonds; use prior to alkylation; compatible with both IAA and NEM protocols. |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | 1-50 mM (5-20 mM typical) | Reduces disulfide bonds; more stable than DTT; effective in MeOH-containing buffers. |

| Tributylphosphine (TBP) | 1-10 mM (2-5 mM typical) | Alternative reducing agent; does not interfere with iodoacetamide reactivity. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Manufacturer's recommendation | Prevents proteolytic degradation during sample preparation; avoid thiol-based inhibitors. |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Variable | Isotope-labeled IAA/NEM derivatives (e.g., d5-NEM, 13C6-IAA) for quantitative proteomics. |

Iodoacetamide and N-ethylmaleimide serve as complementary tools in DUB inhibitor research and cysteine-targeted proteomics. IAA offers advantages in proteomic applications requiring specific, irreversible cysteine modification under neutral to alkaline conditions, while NEM provides superior kinetics and effectiveness across broader pH ranges, including mildly acidic environments. Concentration optimization remains critical, with recommended working ranges of 10-15 mM for IAA and 5-10 mM for NEM in typical DUB inhibition protocols. Researchers should select alkylating agents based on specific experimental requirements, including pH constraints, desired reaction kinetics, and compatibility with downstream analytical techniques. Systematic optimization of concentration, incubation time, and reaction conditions ensures maximal target enzyme inhibition while minimizing non-specific protein modifications that could compromise experimental outcomes.

The Critical Need for DUB Inhibition in Ubiquitinome Studies

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory network in cellular homeostasis, with deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) serving as master regulators of this intricate process. DUBs are a class of proteases that specifically remove ubiquitin from substrate proteins, thereby reversing the action of E3 ubiquitin ligases and controlling the fate of ubiquitinated proteins [21]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, which can be divided into seven subfamilies based on their catalytic domain architecture: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Machado-Josephin domain-containing proteases (MJDs), MIU-containing novel DUB family (MINDY), zinc finger-containing ubiquitin peptidase 1 (ZUP1), and JAB1/MPN/MOV34 (JAMM/MPN+) metalloproteases [22]. These enzymes collectively regulate diverse cellular processes including protein degradation, localization, activation, and signal transduction [21] [23].

The fundamental role of DUB inhibition in ubiquitinome studies stems from the need to capture transient ubiquitination events that would otherwise be erased by endogenous DUB activity. By employing DUB inhibitors, researchers can "freeze" the ubiquitinome at a specific state, enabling accurate assessment of ubiquitination dynamics and identification of novel substrates [24]. This approach has revealed that DUBs and the proteasome regulate largely distinct networks of ubiquitinated substrates, with DUBs controlling at least 40,000 unique ubiquitination sites involved in critical processes including autophagy, apoptosis, genome integrity, and signal transduction [24]. Within the context of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and iodoacetamide (IAA) concentration optimization research—critical cysteine protease inhibitors used in ubiquitinome studies—understanding the precise application and limitations of DUB inhibitors becomes paramount for experimental accuracy and reproducibility.

Key Findings: Differential Regulation by DUBs and the Proteasome

Recent comparative ubiquitinome analyses have revealed distinct substrate preferences and regulatory networks controlled by DUBs versus the proteasome. These findings underscore the critical importance of specifically targeting DUB activity to comprehensively understand ubiquitin signaling dynamics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of DUB and Proteasome Substrate Regulation

| Regulatory Aspect | DUB-Mediated Regulation | Proteasome-Mediated Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Degradation-independent ubiquitin signaling [24] | Protein degradation and turnover [24] |

| Ubiquitination Sites | Regulates >40,000 unique sites [24] | Smaller, more specific set of sites [24] |

| Key Pathways | Autophagy, apoptosis, DNA repair, transcription, signal transduction [24] | Cell cycle progression, protein quality control [21] |

| Inhibition Consequences | PARP1 hyper-ubiquitination and activation [24] | Accumulation of canonical proteasome substrates [24] |

| Kinetics of Substrate Processing | Rapid turnover (within 1-3 hours) [24] | Slower, more regulated degradation [24] |

The differential effects of DUB inhibition extend to specific biological processes. For instance, chemical inhibition of DUBs using PR619 (a broad-spectrum cysteine DUB inhibitor) or genetic ablation of specific DUBs results in hyper-ubiquitination of PARP1, consequently enhancing its enzymatic activity [24]. This finding demonstrates how DUB inhibition can directly modulate the activity of central regulatory proteins beyond affecting their stability. Similarly, DUBs play critical roles in mitotic progression through regulation of key substrates such as the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and various mitotic kinases [23].

Table 2: Selected DUB Inhibitors and Their Applications in Ubiquitinome Studies

| Inhibitor | Target Specificity | Cellular Applications | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR619 | Broad-spectrum cysteine DUB inhibitor [24] | Global ubiquitinome profiling [24] | Revealed DUB-specific regulatory networks encompassing >40,000 ubiquitination sites [24] |

| AZ-1 | USP25/USP28 dual inhibitor [25] | Host-pathogen interactions; immune signaling [25] | Enhanced bacterial clearance; suppressed NF-κB signaling [25] |

| VCPIP1 Inhibitor | VCPIP1 (70 nM potency) [26] | Target validation; chemical probe [26] | Demonstrated feasibility of targeting understudied DUBs with nanomolar potency [26] |

| VLX1570 | USP14/UCHL5 proteasomal DUBs [21] | Multiple myeloma models [21] | Synergistic effect with bortezomib in proteasome inhibitor-resistant cells [21] |

Experimental Protocols for DUB Inhibition Studies

High-Throughput Screening for DUB Inhibitors

The identification of selective DUB inhibitors requires robust screening methodologies. Recent advances have established a high-throughput fluorogenic ubiquitin-rhodamine (Ub-Rho) assay that enables parallel screening of compound libraries against multiple DUBs [27].

Protocol: Fluorogenic DUB Activity Assay

DUB Expression and Purification

- Clone DUBs into expression vectors (e.g., pET28 with N-terminal 6xHis tag or pGEX6P1 with N-terminal GST tag) [27]

- Transform BL21(DE3) Competent E. coli with DUB plasmid and grow on LB plates with appropriate antibiotics (100 μg/mL ampicillin or 50 μg/mL kanamycin) at 37°C for 16-18 hours [27]

- Inoculate a single colony into 5 mL LB medium with antibiotics and grow at 37°C with orbital rotation (1.12 × g) for 16-18 hours [27]

- Dilute culture into 1 L LB medium and grow until OD600 reaches 0.8-1.0 [27]

- Induce protein expression with 100 mg/L IPTG and incubate at 16°C with orbital rotation for 18-24 hours [27]

- Pellet cells by centrifugation at 4,540 × g at 4°C for 20 minutes [27]

Protein Purification

- Resuspend cell pellet in 50-100 mL lysis buffer (25 mM Tris pH 8, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 M NaCl) and stir at 4°C for 30 minutes [27]

- Add PMSF to 10 μg/mL and lyse by sonication on ice (12 cycles of 10 seconds sonication at 70% amplitude with 5 seconds rest) [27]

- Centrifuge lysate at 30,000 × g for 40 minutes at 4°C [27]

- Incubate supernatant with equilibrated Ni-NTA Agarose (for 6xHis-tagged DUBs) or Glutathione Agarose (for GST-tagged DUBs) for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation [27]

- Wash with appropriate buffer (25 mM Tris pH 8, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 M NaCl, 25 mM imidazole for 6xHis-tagged DUBs) [27]

- Elute with elution buffer (25 mM Tris pH 8, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 M NaCl, 300 mM imidazole for 6xHis-tagged DUBs) [27]

- Concentrate using Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units and further purify by FPLC with Superdex 200 size exclusion column [27]

Enzymatic Assay

- Prepare assay buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT) [27]

- Dilute purified DUBs to appropriate concentration in assay buffer

- Pre-incubate DUBs with compounds or DMSO control for 15 minutes at room temperature

- Initiate reaction by adding Ub-Rho substrate (final concentration 100-500 nM)

- Monitor fluorescence (excitation 485 nm, emission 535 nm) continuously for 30-60 minutes

- Calculate inhibition percentage relative to DMSO controls

Chemoproteomic ABPP Screening Platform

Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) has emerged as a powerful method for assessing compound selectivity against endogenous DUBs in complex proteomes [26].

Protocol: Competitive ABPP for DUB Inhibitor Screening

Cellular Extract Preparation

- Culture HEK293 cells in appropriate medium

- Harvest cells and lyse in PBS pH 7.4 containing 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors

- Clarify lysate by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C

- Determine protein concentration and adjust to 2-4 mg/mL

Compound Treatment and ABPP

- Incubate cell extracts with library compounds (50 μM final concentration) or DMSO control for 30 minutes at room temperature [26]

- Add DUB ABP mixture (biotin-Ub-VME and biotin-Ub-PA in 1:1 ratio) to a final concentration of 100-500 nM and incubate for 1 hour at room temperature [26]

- Quench reaction with SDS sample buffer containing 10 mM DTT

Sample Processing for Mass Spectrometry

- Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE (8% Bis-Tris gels)

- Excise entire lanes and digest with trypsin

- Label peptides with isobaric TMT multiplexed reagents [26]

- Enrich biotinylated peptides using streptavidin beads [26]

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS using true nanoflow LC columns with integrated electrospray emitters [26]

Data Analysis

- Identify DUBs by searching MS data against human protein databases

- Quantify TMT reporter ions to determine relative ABP labeling

- Calculate percentage inhibition relative to DMSO controls

- Define hit compounds as those showing ≥50% inhibition of ABP labeling for specific DUBs [26]

Diagram 1: ABPP Screening Workflow for DUB Inhibitor Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DUB Inhibition Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad-Spectrum DUB Inhibitors | PR619 [24] | Global DUB inhibition; ubiquitinome stabilization | Inhibits cysteine proteases but not metalloproteases [24] |

| Selective DUB Inhibitors | AZ-1 (USP25/USP28) [25], VLX1570 (USP14/UCHL5) [21] | Target validation; pathway analysis | Demonstrate on-target effects through genetic validation [25] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Biotin-Ub-VME, Biotin-Ub-PA [26] | DUB activity profiling; inhibitor screening | Used in 1:1 combination for comprehensive DUB coverage [26] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib [24] | Comparative ubiquitinome analysis | Distinct effects compared to DUB inhibitors [24] |

| E1 Inhibitor | TAK243 [24] | Control for ubiquitination dynamics | Blocks new ubiquitination events [24] |

| NEM/IAA | N-ethylmaleimide, Iodoacetamide | Cysteine protease inhibition; sample preparation | Critical concentration optimization required for specific applications |

DUB Regulation and Signaling Pathways

DUBs are themselves subject to complex regulatory mechanisms, including post-translational modifications (PTMs) that control their activity, stability, and subcellular localization [22]. Understanding these regulatory mechanisms is essential for contextualizing DUB inhibitor effects and interpreting ubiquitinome data.

Key Regulatory PTMs of DUBs:

Phosphorylation: Multiple DUBs including OTUD4, OTUD5, and OTULIN are regulated by phosphorylation, which modulates their ubiquitin binding capacity and substrate specificity [22]. For instance, phosphorylation of OTUD4 enhances its binding to and hydrolysis of K63-linked ubiquitin chains [22].

Ubiquitination: Several DUBs undergo auto-ubiquitination or heterologous ubiquitination, which can either promote or inhibit their activity. Monoubiquitination of UCHL1 inhibits its binding to ubiquitin, while ubiquitination of ataxin-3 enhances ubiquitin binding [22].

Oxidation and Hydroxylation: The catalytic cysteine residues of DUBs are particularly sensitive to oxidative modification. Hydroxylation of OTUB1 promotes its interaction with metabolism-associated proteins such as UBE2N/UBC13, while hydroxylation of Cezanne inhibits ubiquitin binding [22].

SUMOylation and Acetylation: These modifications provide additional layers of regulation, influencing DUB stability, protein-protein interactions, and catalytic activity [22].

Diagram 2: Post-Translational Regulation of DUB Activity

The critical need for DUB inhibition in ubiquitinome studies is further emphasized by the rapid kinetics of DUB-mediated substrate processing. Combination treatments with the E1 inhibitor TAK243 have demonstrated that DUBs can turnover the bulk of ubiquitin conjugates within 1-3 hours, highlighting their profound impact on ubiquitin dynamics [24]. This rapid regulation necessitates effective DUB inhibition strategies to accurately capture the cellular ubiquitinome.

DUB inhibition represents an indispensable component of comprehensive ubiquitinome studies, enabling researchers to unravel the complex dynamics of ubiquitin signaling. The integration of specific DUB inhibitors with advanced proteomic methodologies has revealed distinct regulatory networks controlled by DUBs that would otherwise remain obscured. As the field advances, the optimization of inhibitor specificity, combination treatments, and contextual application will continue to enhance our understanding of the ubiquitin code and its multifaceted roles in health and disease. The ongoing development of selective chemical probes for understudied DUBs, coupled with rigorous validation in physiological models, promises to unlock new therapeutic opportunities targeting the UPS across diverse pathological conditions.

Basic Principles of Concentration Optimization for Effective Inhibition

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) represent an emerging drug target class of approximately 100 proteases that regulate ubiquitin dynamics through catalytic cleavage of ubiquitin from protein substrates and ubiquitin precursors [28] [29]. Despite growing interest in their biological function and therapeutic potential, the development of selective DUB inhibitors has been challenging, with few selective small-molecule inhibitors and no approved drugs currently available [28] [29]. Concentration optimization of inhibitory compounds is fundamental to this discovery process, ensuring both efficacy against the intended target and selectivity over related enzymes. This document outlines key principles and methodologies for optimizing inhibitor concentrations across various experimental contexts, providing researchers with a structured framework for advancing DUB inhibitor development.

Foundational Concepts in DUB Inhibition

The Druggability of Deubiquitinating Enzymes

DUBs are broadly classified into cysteine proteases and zinc metalloproteases based on their catalytic mechanisms [29]. The approximately 90 cysteine protease DUBs are further subdivided into six families: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Machado-Joseph disease proteases (MJDs), motif interacting with ubiquitin (MIU)-containing novel DUB family (MINDY) proteases, and zinc finger-containing ubiquitin peptidase 1 (ZUP1) [30]. This diversity presents both challenges and opportunities for selective inhibitor development.

The therapeutic potential of targeting DUBs has attracted significant attention due to their druggable active sites and dysregulation in various diseases, including cancer, inflammatory disorders, and neurodegenerative conditions [30]. DUBs have been implicated as critical determinants of cellular homeostasis, with their dysfunction linked to numerous pathological states [30].

Key Parameters for Inhibitor Optimization

Effective inhibitor optimization requires careful consideration of multiple parameters:

- Potency: Concentration required for half-maximal inhibition (IC50)

- Selectivity: Specificity for target DUB versus related enzymes

- Cellular Activity: Ability to engage the target in a physiological context

- Toxicity: Cellular effects at working concentrations

Recent studies demonstrate that parallel screening of multiple DUBs against the same compound library facilitates identification of selective inhibitors by enabling direct comparison of potency across enzyme families [29].

Experimental Approaches for Concentration Optimization

In Vitro Biochemical Assays

Fluorogenic Ubiquitin-Rhodamine Assay: This robust assay platform has been widely adapted for high-throughput screening of DUB inhibitors [27] [29]. The assay utilizes recombinant DUB enzymes and a fluorogenic DUB substrate, ubiquitin-rhodamine110 (Ub-Rho), where DUB-mediated cleavage releases fluorescent rhodamine.

Key Optimization Steps:

- Buffer Screening: Comprehensive assessment of buffer composition, pH, salt concentration, BSA, EDTA, detergent, and reducing agents to maximize enzymatic activity and assay robustness [29].

- Enzyme Purification: Recombinant DUB expression with either 6xHis-tags (pET28 vectors) or GST-tags (pGEX6P1 vectors) in BL21(DE3) competent E. coli, followed by affinity purification and size exclusion chromatography [27].

- Assay Miniaturization: Adaptation to high-throughput formats while maintaining signal-to-noise ratios [27].

Typical Screening Concentrations:

- Primary screening: 20-50 μM compound concentration [29]

- Dose-response confirmation: Serial dilutions from high micromolar to low nanomolar range

Table 1: Representative DUBs for Screening and Key Characteristics

| DUB | Family | Therapeutic Interest | Expression System |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP7 | USP | Cancer, neurodegeneration | E. coli, 6xHis-tag |

| USP8 | USP | Cancer, endosomal sorting | E. coli, GST-tag |

| USP28 | USP | Cancer, DNA repair | E. coli, 6xHis-tag |

| UCHL1 | UCH | Parkinson's disease | E. coli, 6xHis-tag |

| OTUD3 | OTU | Cancer, signaling pathways | E. coli, GST-tag |

Cellular Target Engagement Assessment

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP): This approach utilizes activity-based probes (ABPs) featuring a reactive group that covalently binds to the DUB active site, a specific binding group/linker, and a reporter tag for detection or affinity purification [31]. ABPP enables assessment of compound potency and selectivity against endogenous DUBs in cellular contexts, revealing potential off-target effects and drug efficacy [31].

ABPP-HT Workflow: A semi-automated proteomic sample preparation workflow increases throughput approximately ten-fold while preserving enzyme profiling characteristics [31]. Key steps include:

- Cell lysis and clarification

- Compound incubation (typically at 50 μM for primary screening)

- ABP labeling with probes like HA-Ub-PA (hemagglutinin-ubiquitin-propargylamine)

- Immunoaffinity purification

- LC-MS/MS analysis for identification and quantification

Concentration Optimization Strategy:

- Primary screen: Single concentration (e.g., 50 μM) to identify preliminary hits

- Confirmatory testing: Dose-response curves with multiple concentrations (e.g., 0.1-100 μM)

- Selective compound definition: ≥50% blockade of ABP labeling for specific DUBs at tested concentrations [26]

Diagram 1: ABPP-HT workflow for cellular target engagement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DUB Inhibitor Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Optimization Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pET28 (6xHis-tag), pGEX6P1 (GST-tag) | Recombinant DUB production | Affinity tag selection based on DUB characteristics; transformation in BL21(DE3) E. coli |

| Purification Resins | Ni-NTA Agarose, Glutathione Superflow Agarose | Affinity purification of tagged DUBs | Resin capacity optimization; imidazole concentration for elution (e.g., 300 mM) |

| Activity-Based Probes | HA-Ub-PA, HA-Ub-VME, Biotin-Ub-PA | Cellular target engagement assessment | Warhead selection (PA vs. VME); tag choice (HA vs. biotin) for detection/purification |

| Fluorogenic Substrates | Ubiquitin-Rhodamine110 (Ub-Rho) | In vitro enzymatic activity measurement | Buffer optimization (pH, salts, reducing agents); substrate concentration titration |

| Positive Control Inhibitors | PR-619 (broad-spectrum), P22077 (USP7-specific) | Assay validation and standardization | Concentration range testing; selectivity confirmation across DUB panel |

Concentration Optimization Framework

Tiered Screening Approach

A structured, multi-tiered screening cascade enables efficient identification and validation of selective DUB inhibitors [29]:

Primary Screening:

- Compound concentration: 20-50 μM

- Platform: Fluorogenic Ub-Rho assay or ABPP-HT

- Output: Initial actives against target DUB

Dose-Response Confirmation:

- Concentration range: Typically 0.1-100 μM (serial dilutions)

- Counter-screening: Against minimum of 2-8 additional DUBs

- Output: Potency (IC50) and preliminary selectivity assessment

Orthogonal Validation:

- Cellular activity assessment

- Expanded selectivity profiling across DUB families

- Secondary assays (e.g., immunoprecipitation, deubiquitination assays)

- Output: Comprehensive selectivity and efficacy profile

Selectivity and Potency Filtering

Implementation of strategic filters facilitates prioritization of promising compounds:

- Selectivity filters: Identify compounds with activity against single DUB among screening panel

- Potency filters: Rank compounds by IC50 values against target DUB

- Chemical property filters: Eliminate compounds with undesirable features (PAINS)

Recent studies indicate that parallel screening against multiple DUB families enables rapid identification of selective inhibitors by providing immediate selectivity data [29]. For example, screening against eight different DUBs spanning USP, UCH, and OTU families facilitated identification of highly selective inhibitors for specific DUBs including USP28 [29].

Diagram 2: Tiered screening approach for DUB inhibitors

Case Studies and Applications

Successful DUB Inhibitor Development

The principles outlined above have enabled development of best-in-class probes for several DUBs:

USP28 Inhibitors: Parallel screening identified selective starting points that were optimized into high-quality chemical probes [29]. These compounds demonstrated nanomolar potency and excellent selectivity against related USPs.

VCPIP1 Probe Development: A rationally designed covalent library paired with ABPP screening identified an azetidine hit that was optimized into a selective 70 nM covalent inhibitor of the understudied DUB VCPIP1 [26]. This achievement highlights how targeted library design combined with appropriate screening methodologies can yield potent inhibitors even for less-characterized DUBs.

Structural Considerations for Concentration Optimization

Analysis of DUB-ligand and DUB-ubiquitin co-structures reveals multiple interaction sites that inform inhibitor design and concentration optimization [26]:

- Catalytic site: Targeted by electrophilic warheads (cyano, α,β-unsaturated amides, chloroacetamide)

- Leucine-binding pocket: Engaged by aromatic and heterocycle moieties

- Ubiquitin-binding channels: Addressed through linker diversification (length, flexibility, H-bond donors/acceptors)

These structural insights enable rational design of inhibitors with improved potency, potentially lowering required concentrations for effective target engagement.

Concentration optimization for effective DUB inhibition requires integrated experimental strategies combining in vitro biochemical assays with cellular target engagement assessment. The framework outlined herein—emphasizing tiered screening, orthogonal validation, and structural considerations—provides a roadmap for advancing DUB inhibitor discovery. As the field progresses, continued refinement of these approaches will undoubtedly yield increasingly selective and potent chemical probes, accelerating both biological understanding and therapeutic development for this important enzyme class.

Practical Guide: Implementing NEM and IAA in DUB Workflows

Standard Protocols for Lysate Preparation with NEM/IAA

In deubiquitylase (DUB) inhibitor research, maintaining the native ubiquitination state of proteins during lysate preparation is paramount. The dynamic and reversible nature of ubiquitination, governed by the opposing actions of E3 ligases and DUBs, presents a significant experimental challenge. Upon cell lysis, the loss of cellular compartmentalization allows endogenous DUBs to rapidly cleave ubiquitin chains from substrates, potentially obscuring the true biological state and the effects of experimental DUB inhibitors [32]. To address this, the inclusion of covalent DUB inhibitors in lysis buffers is a standard and necessary practice.

N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) and Iodoacetamide (IAA) are fundamental reagents used to preserve the ubiquitinome by irreversibly inhibiting cysteine-dependent DUBs and other thiol-dependent enzymes [33] [32]. As alkylating agents, they covalently modify the crucial cysteine residues in the active sites of the majority of DUBs, thereby "freezing" ubiquitination states at the moment of lysis. The optimization of their concentration is a critical parameter, representing a balance between achieving complete DUB inhibition and minimizing off-target alkylation of other proteins, which could affect downstream analyses like immunoblotting or mass spectrometry. This protocol details standardized methods for lysate preparation incorporating NEM and IAA, specifically framed within the context of concentration optimization for DUB inhibitor research.

The following table summarizes the core parameters for the use of NEM and IAA in lysate preparation for ubiquitination studies. These concentrations serve as a starting point for optimization.

Table 1: Standard Concentration Ranges for NEM and IAA in Lysate Preparation

| Reagent | Standard Working Concentration | Key Considerations & Rationale | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | 1-10 mM [34] [33] | Broad-spectrum, fast-acting. Solutions are light-sensitive and unstable in aqueous buffer; must be added fresh. | General ubiquitinome preservation for immunoblotting, Ub-AMC activity assays [34]. |

| Iodoacetamide (IAA) | 5-20 mM [35] | More stable than NEM but may react more slowly. Often preferred for mass spectrometry (MS) workflows to avoid side reactions. | Sample preparation for mass spectrometry-based proteomics [35]. |

It is important to note that while these ranges are well-established, the optimal concentration within this range may depend on the specific cell type, the abundance of DUBs, and the stringency of the lysis buffer. A dose-response verification of DUB inhibition is recommended for critical applications.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Denaturing Lysis for Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment

This protocol is designed for robust preservation of ubiquitin conjugates and is suitable for downstream applications such as immunoblotting, ubiquitinated protein enrichment using tools like OtUBD resin, and proteomic analysis [33] [32].

A. Reagents and Solutions

- Lysis Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40 or SDS (for denaturing conditions), and 5-20 mM IAA or 1-10 mM NEM [35] [33].

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail: EDTA-free cocktail tablet or solution.

- Phosphatase Inhibitors: (Optional) If phosphorylated ubiquitin or substrates are of interest.

- NEM Stock Solution: 500 mM in ethanol or DMSO. Prepare fresh.

- IAA Stock Solution: 500 mM in water. Prepare fresh and protect from light.

B. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Pre-cool Equipment: Ensure centrifuges and rotors are pre-cooled to 4°C.

- Prepare Lysis Buffer: Add protease inhibitors and the selected alkylating agent (NEM or IAA) to the lysis buffer immediately before use.

- Harvest Cells: Aspirate media from cultured cells and wash once with ice-cold PBS.

- Lyse Cells: Add an appropriate volume of lysis buffer directly to the cell culture dish (e.g., 100-200 µL for a 6-well plate). Gently rock the dish on ice for 5-10 minutes. For tissues, homogenize the tissue in lysis buffer using a Dounce homogenizer or a mechanical homogenizer on ice.

- Clarify Lysate: Scrape the lysate off the dish and transfer it to a pre-chilled microcentrifuge tube. Centrifuge at 14,000-16,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble debris.

- Collect Supernatant: Carefully transfer the clarified supernatant to a new pre-chilled tube.

- Protein Quantification: Determine protein concentration using a compatible assay (e.g., BCA or Bradford assay).

- Immediate Use or Storage: Proceed immediately to downstream applications or snap-freeze the lysate in aliquots at -80°C to prevent thaw-refreeze cycles.

Protocol 2: Validation of DUB Inhibition via Ub-AMC Hydrolysis Assay

This functional assay validates the efficacy of NEM/IAA in inhibiting DUB activity within the prepared lysates, using the fluorogenic substrate Ub-AMC [34].

A. Reagents and Solutions

- Assay Buffer: 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 5 mM DTT. Note: DTT is added after lysate preparation to quench residual NEM/IAA and allow only the pre-inhibited DUBs to be measured.

- Ub-AMC Substrate: 100-500 nM working concentration in assay buffer.

- Positive Control: A broad-spectrum DUB inhibitor like PR-619.

B. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Set Up Reactions: In a black 96-well plate, dilute lysates (prepared with or without NEM/IAA) in assay buffer.

- Initiate Reaction: Add the Ub-AMC substrate to each well to start the reaction.

- Measure Fluorescence: Immediately monitor the increase in fluorescence (Ex/Em ~355/460 nm) using a plate reader over 30-60 minutes at 37°C.

- Data Analysis: The initial rate of fluorescence increase is proportional to DUB activity. Lysates prepared with optimized concentrations of NEM/IAA should show a significant reduction (>80-90%) in the hydrolysis rate compared to untreated controls, confirming effective DUB inhibition during lysis.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

DUB Inhibition Logic in Ubiquitinome Preservation

The following diagram illustrates the core logic of using NEM/IAA to preserve the cellular ubiquitinome by preventing DUB activity during and after cell lysis.

Experimental Workflow for Lysate Preparation and Analysis

This workflow outlines the end-to-end process for preparing lysates with DUB inhibition and proceeding to key downstream applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for DUB-Inhibited Lysate Preparation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Role | Specific Example & Application |

|---|---|---|

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Broad-spectrum, irreversible cysteine protease/DUB inhibitor. Preserves ubiquitin chains during lysis [34] [33]. | Used in Ub-AMC assays to demonstrate baseline DUB activity and in lysis buffers for immunoblotting [34]. |

| Iodoacetamide (IAA) | Irreversible alkylating agent for cysteine residues. Inhibits DUBs and prevents disulfide bond formation, often preferred for MS [35]. | Included in lysis buffers for subsequent ubiquitination site mapping by mass spectrometry [35]. |

| Ub-AMC (Ubiquitin-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin) | Fluorogenic substrate for measuring deubiquitinating enzyme activity. Cleavage releases fluorescent AMC [34]. | Validating the efficacy of NEM/IAA inhibition in lysates; high-throughput screening of DUB inhibitors [34]. |

| Tandem-repeated Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Engineered high-affinity ubiquitin binders used to enrich ubiquitinated proteins from complex lysates, protecting them from DUBs and proteasomal degradation during purification [32]. | Pull-down of polyubiquitinated proteins for identification and analysis following lysis with NEM/IAA. |

| OtUBD Affinity Resin | A high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain from O. tsutsugamushi used to enrich mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins from lysates under native or denaturing conditions [33]. | A versatile tool for ubiquitinome enrichment from lysates prepared with NEM/IAA, compatible with immunoblotting and proteomics [33]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | Antibodies that recognize a specific topology of polyubiquitin chain (e.g., K48, K63, M1-linear) [32]. | Detecting changes in specific chain types in lysates by immunoblotting after DUB-inhibited lysis. |

Using TUBEs with DUB Inhibitors for Native Protein Isolation

This application note provides a detailed methodology for the synergistic use of Tandem-repeated Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) and deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) inhibitors to isolate native ubiquitylated proteins from cellular extracts. The protocol addresses a major challenge in ubiquitin research—the rapid reversal of ubiquitylation by endogenous DUBs during protein extraction. By implementing TUBEs as molecular traps alongside DUB inhibitors, researchers can achieve superior protection and purification of poly-ubiquitylated proteins in their native state, enabling more accurate characterization of the ubiquitinome under physiological and pathological conditions.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory pathway for protein degradation and signaling, with deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) playing a counter-regulatory role by removing ubiquitin modifications. Approximately 100 DUBs encoded by the human genome finely balance ubiquitination processes to maintain cellular homeostasis [36]. Research into ubiquitin dynamics has been hampered by the technical challenge of preserving labile ubiquitin modifications during experimental procedures, as DUBs remain active in cell lysates and rapidly deconjugate ubiquitin from substrates [37].

Traditional approaches using cysteine protease inhibitors like iodoacetamide (IAA) and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) provide partial protection but present limitations, including potential artifacts in mass spectrometry analysis [37]. This protocol describes an optimized integrated method leveraging the complementary strengths of TUBEs and DUB inhibitors to overcome these limitations, enabling robust isolation of native ubiquitylated proteins for downstream applications including immunoblotting, mass spectrometry, and functional studies.

Background Principles

The Ubiquitin System and DUB Biology

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are specialized proteases that cleave the isopeptide bond at the C-terminus of ubiquitin, reversing ubiquitin signaling and maintaining cellular ubiquitin homeostasis [21]. These enzymes regulate diverse cellular processes including protein degradation, localization, and activity through three primary mechanisms:

- Generation of free ubiquitin from precursor proteins

- Cleavage of polyubiquitin chains at specific positions

- Complete removal of ubiquitin chains from substrate proteins [21]

DUBs are classified into seven subfamilies based on their catalytic mechanisms and structural features: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USP), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCH), ovarian tumor proteases (OTU), Machado-Josephin domain proteases (MJD), motif interacting with ubiquitin-containing novel DUB family (MINDY), JAB1/MPN/Mov34 metalloenzymes (JAMM), and zinc finger-containing ubiquitin peptidases (ZUFSP) [36]. The majority are cysteine proteases except for the JAMM family, which are zinc metalloproteases.

TUBE Technology Fundamentals

Tandem-repeated Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) are engineered proteins containing four tandem ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains that function as high-affinity ubiquitin chain receptors [37]. This multivalent design creates a synergistic binding effect, resulting in several key advantages:

- Markedly Enhanced Affinity: TUBEs bind tetra-ubiquitin with 100-1000-fold higher affinity compared to single UBA domains

- Protection Function: TUBEs shield bound ubiquitin chains from both proteasomal degradation and DUB activity

- Linkage Versatility: Different UBA domains can be selected to recognize various ubiquitin chain linkages

- Native Condition Compatibility: Effective operation under physiological conditions without denaturants

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for TUBE-based Native Protein Isolation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TUBE Reagents | HR23A TUBE, Ubiquilin 1 TUBE | High-affinity ubiquitin binding; HR23A TUBE: KD = 5.79 nM (Lys63 chains), Ubiquilin 1 TUBE: KD = 0.66 nM (Lys63 chains) [37] |

| DUB Inhibitors | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), Iodoacetamide (IAA), PR-619, Ubiquitin Vinyl Sulfone (UbVS) | Broad-spectrum cysteine protease inhibition; NEM/IAA: Traditional inhibitors with potential side effects; PR-619: Potent cell-permeable inhibitor; UbVS: Irreversible pan-DUB inhibitor [37] [38] |

| Specialized Inhibitors | AZ-1 (USP25 inhibitor), XL177A (USP7 inhibitor), Capzimin | Selective DUB targeting; AZ-1: Host-directed antimicrobial therapy; XL177A: Selective USP7 inhibition; Capzimin: Proteasome-associated DUB inhibition [39] [26] |

| Affinity Tags | GST-TUBE, His6-TUBE, SV5-TUBE | TUBE immobilization and detection; GST: Glutathione resin purification; His6: Nickel affinity purification; SV5: Immunodetection [37] |

| Ubiquitin Probes | Biotin-Ub-VME, Biotin-Ub-PA | Activity-based protein profiling; Enable monitoring of DUB activity and inhibitor efficacy in cellular extracts [26] |

Quantitative Binding Parameters

Table 2: Equilibrium Dissociation Constants (KD) for TUBE-Ubiquitin Interactions