Optimizing Ubiquitin Chain Resolution: A Practical Guide to Gel Percentage and Buffer Selection for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive, practical guide for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to optimize the separation and analysis of ubiquitin chains via SDS-PAGE.

Optimizing Ubiquitin Chain Resolution: A Practical Guide to Gel Percentage and Buffer Selection for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, practical guide for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to optimize the separation and analysis of ubiquitin chains via SDS-PAGE. Ubiquitin chains, critical regulators of cellular processes, present a unique analytical challenge due to their diverse linkage types, lengths, and conformations, which cause atypical migration on gels. We explore the foundational principles of ubiquitin chain complexity and its direct impact on electrophoretic mobility. The guide details methodological considerations for gel percentage selection and buffer composition, supported by troubleshooting strategies for common issues like smearing and poor resolution. Finally, we outline validation techniques, including deubiquitinase-based assays (UbiCRest) and mass spectrometry, to confirm chain architecture. This resource synthesizes current methodologies to enable accurate interpretation of ubiquitination in signaling, proteostasis, and disease contexts.

Understanding Ubiquitin Chain Complexity: Why Standard Gel Protocols Often Fail

Troubleshooting Common Ubiquitin Research Challenges

This section addresses frequent experimental issues and provides targeted solutions to improve the reliability of your ubiquitin research.

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Ubiquitin Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smear-like ubiquitin signals on Western blot [1] | Heterogeneous chain lengths and multiple ubiquitylation sites on a single substrate. | Use chain-length analysis methods like Ub-ProT to deconvolute the smear into discrete chain lengths [2]. |

| Weak ubiquitination signal in pull-downs | Low abundance of ubiquitinated proteins; modification is transient or reversible. | Pre-treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., 5-25 µM MG-132 for 1-2 hours) prior to harvesting to preserve ubiquitination [1]. Include deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide (NEM)) in your lysis buffer [3]. |

| Inability to distinguish specific ubiquitin linkages | Use of non-linkage-specific reagents (e.g., pan-ubiquitin antibodies or traps). | Employ linkage-specific TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) for enrichment or use linkage-specific antibodies for detection in Western blot [4] [1]. |

| Poor enrichment of monoubiquitinated proteins | Use of affinity tools optimized for polyubiquitin chains. | Use a high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain like OtUBD, which efficiently enriches both mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary functions of the different ubiquitin linkage types?

The biological outcome of ubiquitination is largely dictated by the type of linkage used to form polyubiquitin chains. The most well-characterized linkages and their functions are summarized below.

Table: Primary Functions of Major Ubiquitin Linkages

| Linkage Type | Chain Length | Primary Downstream Signaling Event |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | Polymeric | Targeted protein degradation by the proteasome [4] [1]. |

| K63 | Polymeric | Immune responses, inflammation, signal transduction, and protein trafficking [4] [1]. |

| K11 | Polymeric | Cell cycle progression and proteasome-mediated degradation [1] [5]. |

| K6 | Polymeric | Antiviral responses, autophagy, mitophagy, and DNA repair [1]. |

| M1 (Linear) | Polymeric | Cell death and immune signaling [1]. |

| Monoubiquitination | Monomer | Endocytosis, histone modification, and DNA damage responses [1]. |

Q2: How can I quantitatively measure all ubiquitin linkage types simultaneously in my sample?

The gold-standard method is Ub-AQUA/PRM (Ubiquitin-Absolute Quantification/Parallel Reaction Monitoring) [6] [7]. This mass spectrometry-based approach uses isotopically labeled signature peptides for each of the eight ubiquitin-ubiquitin linkage types as internal standards. When spiked into a trypsin-digested sample, these AQUA peptides allow for direct, highly sensitive, and absolute quantification of the stoichiometry of all linkages simultaneously [6].

Q3: What techniques are available for measuring the length of ubiquitin chains on a substrate?

A novel biochemical method called Ub-ProT (Ubiquitin chain Protection from Trypsinization) has been developed for this purpose [7] [2]. This method uses a trypsin-resistant TUBE (TR-TUBE) to bind and protect substrate-attached ubiquitin chains from trypsin digestion. After the substrate protein is digested, the protected ubiquitin chains are released and analyzed by immunoblotting, revealing the discrete chain lengths that were formerly obscured in a smear [2].

Q4: What are branched ubiquitin chains and why are they important?

Branched (or heterotypic) ubiquitin chains contain more than one type of isopeptide bond linkage. A prominent example is the K11/K48-branched chain, which functions as a potent signal for proteasomal degradation, often "fast-tracking" substrates like mitotic regulators and misfolded proteins for destruction [5]. Recent structural studies show the proteasome has specialized receptors that recognize this specific branched topology, underscoring its unique role in the ubiquitin code [5].

Key Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for two critical techniques in ubiquitin research.

Principle: A trypsin-resistant TUBE (TR-TUBE) protects substrate-bound ubiquitin chains from trypsin digestion, allowing subsequent analysis of intact chain length.

Procedure:

- Prepare Lysate: Lyse cells in a buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination (e.g., containing DUB inhibitors like NEM).

- Incubate with TR-TUBE: Capture ubiquitinated proteins from the lysate using TR-TUBE conjugated to beads.

- Trypsin Digestion: While complexes are bound to the beads, treat them with trypsin under native conditions. Trypsin will cleave and digest the substrate protein and any unprotected ubiquitin, but the chains bound by TR-TUBE remain intact.

- Elute and Analyze: Elute the protected polyubiquitin chains and analyze them by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using an anti-ubiquitin antibody. Compare the ladder pattern to free ubiquitin chains of known length for size estimation.

Ub-ProT Workflow for Chain Length Analysis

Principle: The high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain OtUBD (from Orientia tsutsugamushi) is used to isolate both mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins from complex lysates.

Procedure:

- Resin Preparation: Couple the recombinant OtUBD polypeptide to SulfoLink coupling resin via its cysteine residue.

- Lysate Preparation:

- Native Condition: Use a non-denaturing lysis buffer if you wish to co-purify proteins that interact non-covalently with ubiquitin or ubiquitinated proteins (the "ubiquitin interactome").

- Denaturing Condition: Use a lysis buffer with strong denaturants (e.g., SDS, urea) to isolate only covalently ubiquitinated proteins (the "ubiquitinome").

- Affinity Purification: Incubate the clarified lysate with the OtUBD resin. Wash thoroughly with appropriate buffer.

- Elution: Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins using a buffer containing SDS and DTT for downstream applications like immunoblotting or mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Studying the Ubiquitin Code

| Research Tool | Type | Key Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) [4] [2] | Artificial protein with multiple UBA domains | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitin chains; protects chains from DUBs and proteasomal degradation during isolation. Can be linkage-specific (e.g., K48- or K63-TUBEs). |

| Ubiquitin-Trap (ChromoTek) [1] | Anti-Ubiquitin Nanobody (VHH) | Immunoprecipitation of monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitinylated proteins from a wide range of cell extracts. Not linkage-specific. |

| OtUBD Affinity Resin [3] | High-affinity Ubiquitin-Binding Domain | Efficiently enriches both mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins from crude lysates. Offers native and denaturing workflow options. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies [7] [1] | Antibody | Detect specific ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48, K63) via Western blot or immunofluorescence. Commercially available for K11, K48, K63, and M1 linkages. |

| AQUA Peptides [6] [7] | Isotopically Labeled Peptide | Internal standards for mass spectrometry-based absolute quantification (Ub-AQUA/PRM) of all eight ubiquitin linkage types. |

| Trypsin-Resistant TUBE (TR-TUBE) [2] | Engineered TUBE | Core component of the Ub-ProT method; resistant to trypsin digestion, allowing for protection and analysis of ubiquitin chain length. |

Advanced Topics: Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Branched ubiquitin chains represent a complex layer of regulation within the ubiquitin code. For example, the K48/K63 branched chain has been shown to enhance NF-κB signaling by stabilizing K63 linkages, while also playing a role in proteasomal degradation [7]. The recognition of these chains by the proteasome involves a multivalent mechanism, where the K11/K48-branched chain, for instance, is recognized by a tripartite binding interface involving RPN2 and RPN10, explaining its role as a priority degradation signal [5].

Proteasomal Recognition of a K11/K48-Branched Ubiquitin Chain

Accurately determining molecular weight is a foundational step in biochemical analysis, yet researchers frequently observe discrepancies between calculated and observed molecular weights during gel electrophoresis. This technical guide explores the pivotal role that protein and nucleic acid chain conformation plays in dictating electrophoretic migration. Understanding these principles is particularly crucial for researchers working with complex samples such as ubiquitinated proteins, where conformational diversity can significantly impact resolution and interpretation. The following sections provide targeted troubleshooting guidance and methodological recommendations to optimize your electrophoretic separations.

FAQs: Conformation and Migration

Why do my ubiquitinated proteins show smeared bands instead of discrete bands on SDS-PAGE?

Smearing of ubiquitinated proteins typically results from heterogeneity in chain length and conformation. Unlike uniform protein complexes, polyubiquitin chains can vary greatly in the number of ubiquitin monomers attached and the specific lysine linkages connecting them. This creates a population of molecules with identical molecular weights but different conformational states that migrate at different rates through the gel matrix [8]. To minimize smearing, use higher-percentage gels for shorter ubiquitin chains and lower-percentage gels for longer chains, consider specialized buffer systems like Tris-acetate for improved high-molecular-weight resolution, and include deubiquitylase (DUB) inhibitors (e.g., NEM or IAA) in your lysis buffer to preserve ubiquitin chain integrity [8].

Why do membrane proteins often migrate at unexpected positions on SDS-PAGE?

Membrane proteins frequently exhibit anomalous migration due to their unique detergent-binding properties. Unlike globular proteins that typically bind a consistent amount of SDS (approximately 1.4 g SDS/g protein), transmembrane proteins with abundant hydrophobic regions can bind significantly more detergent – up to 3.4-10 g SDS/g protein as observed in CFTR transmembrane segment studies [9]. This increased detergent binding alters the mass and charge characteristics of the protein-detergent complex, resulting in migration that doesn't correlate with formula molecular weights. The secondary structure also influences this process, with gel shift behavior strongly correlating with helical content (R² = 0.9) [9].

How does DNA conformation affect migration in agarose gels?

DNA conformation significantly impacts migration distance independent of molecular weight. Supercoiled plasmid DNA, being the most compact form, migrates fastest through agarose gels. Linearized DNA migrates at an intermediate rate, while open circular (nicked) DNA, being the bulkiest conformation, migrates slowest [10]. This explains why uncut plasmids typically show three distinct bands on agarose gels despite having identical molecular weights. Always consider conformation when interpreting DNA gel results, and use restriction enzyme digestion to generate uniform linear molecules for accurate size determination [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Resolution of Ubiquitin Chains

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Incorrect Gel Percentage:

- Cause: Using a single-concentration gel for ubiquitin chains of varying lengths.

- Solution: Optimize acrylamide concentration based on target chain length – use 12% gels for resolving mono-ubiquitin and short oligomers, and 8% gels for separating longer polyubiquitin chains (up to 20 ubiquitins) [8].

Suboptimal Buffer System:

- Cause: Using a one-size-fits-all running buffer.

- Solution: Select running buffer based on separation goals: MES buffer improves resolution of 2-5 ubiquitin oligomers, MOPS buffer enhances separation for chains containing ≥8 ubiquitins, and Tris-acetate is superior for proteins in the 40-400 kDa range [8].

Sample Degradation:

- Cause: Inadequate inhibition of deubiquitylases (DUBs) during sample preparation.

- Solution: Include fresh DUB inhibitors in lysis buffer – N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) at 20-50 mM or iodoacetamide (IAA) at similar concentrations. For mass spectrometry applications, prefer NEM as IAA modification can interfere with ubiquitylation site identification [8].

Problem: Smeared or Distorted Bands

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Overheating During Electrophoresis:

Sample Overloading:

- Cause: Too much protein or DNA per well.

- Solution: Reduce loading amount to 0.1-0.2 μg per millimeter of well width for DNA [13]. For proteins, empirically determine optimal loading concentration.

Improper Sample Preparation:

Experimental Protocols

Optimizing Ubiquitin Chain Resolution: Buffer and Gel Selection

Objective: To resolve specific ubiquitin chain lengths by selecting appropriate gel percentages and running buffers.

Materials:

- Pre-casted gradient gels or materials for casting Tris-glycine gels

- MES, MOPS, and Tris-acetate running buffers

- Ubiquitinated protein samples

- DUB inhibitors (NEM or IAA)

- Electrophoresis equipment and power supply

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Lyse cells in buffer containing 50 mM NEM to preserve ubiquitin chains. Boil samples in SDS-containing loading buffer [8].

- Gel Selection:

- Electrophoresis: Run gels at constant voltage (100-150V) with cooling to prevent overheating.

- Transfer and Detection: Use appropriate transfer methods for high-molecular-weight proteins and detect with ubiquitin-specific antibodies.

Expected Results: Discrete bands corresponding to specific ubiquitin chain lengths when the appropriate gel-buffer combination is used, compared to smeared patterns with mismatched conditions.

Analyzing Detergent Binding in Membrane Proteins

Objective: To correlate SDS binding capacity with anomalous migration of membrane proteins.

Materials:

- Helical membrane protein samples (e.g., CFTR transmembrane segments)

- Radiolabeled or fluorescent SDS

- Standard SDS-PAGE equipment

- Gel filtration or equilibrium dialysis equipment

Methodology:

- Incubate membrane proteins with SDS under denaturing conditions [9].

- Separate protein-detergent complexes from free detergent using gel filtration or equilibrium dialysis.

- Quantify bound SDS per gram of protein using appropriate detection methods.

- Run parallel SDS-PAGE to determine apparent molecular weight.

- Compare SDS binding ratios with gel shift behavior ((apparent MW - formula MW)/formula MW × 100%).

Expected Results: Proteins with higher SDS binding ratios (3.4-10 g SDS/g protein) will show greater anomalous migration compared to those with lower binding ratios [9].

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Electrophoresis Buffer Systems for Ubiquitin Chain Resolution

| Buffer System | Optimal Separation Range | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MES (2-(N-morpholino) ethane sulfonic acid) | 2-5 ubiquitin oligomers | Improved resolution of short chains | Poor resolution of long chains |

| MOPS (3-(N-morpholino) propane sulfonic acid) | 8+ ubiquitin chains | Superior separation of long polyubiquitin chains | Less effective for short oligomers |

| Tris-acetate | 40-400 kDa proteins | Broad range resolution for high molecular weight proteins | Not optimized for very short chains |

| Tris-glycine | Up to 20 ubiquitin chains | Versatile for mixed-length samples | Less specific resolution than specialized buffers |

Table 2: Migration Anomalies in Helical Membrane Proteins

| Protein Example | Formula MW (kDa) | Apparent MW (kDa) | Gel Shift (%) | SDS Binding (g SDS/g protein) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-type ATPase c subunit (undecamer) | 97 | 53 | -46 | Not specified |

| Lactose permease | 47 | 33 | -30 | Not specified |

| Phospholamban (monomer) | 6.1 | 9 | +48 | Not specified |

| CFTR TM3/4 hairpins (range) | Varies | Varies | -10 to +30 | 3.4-10 [9] |

| Glycophorin | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 3.4 [9] |

Visualization Diagrams

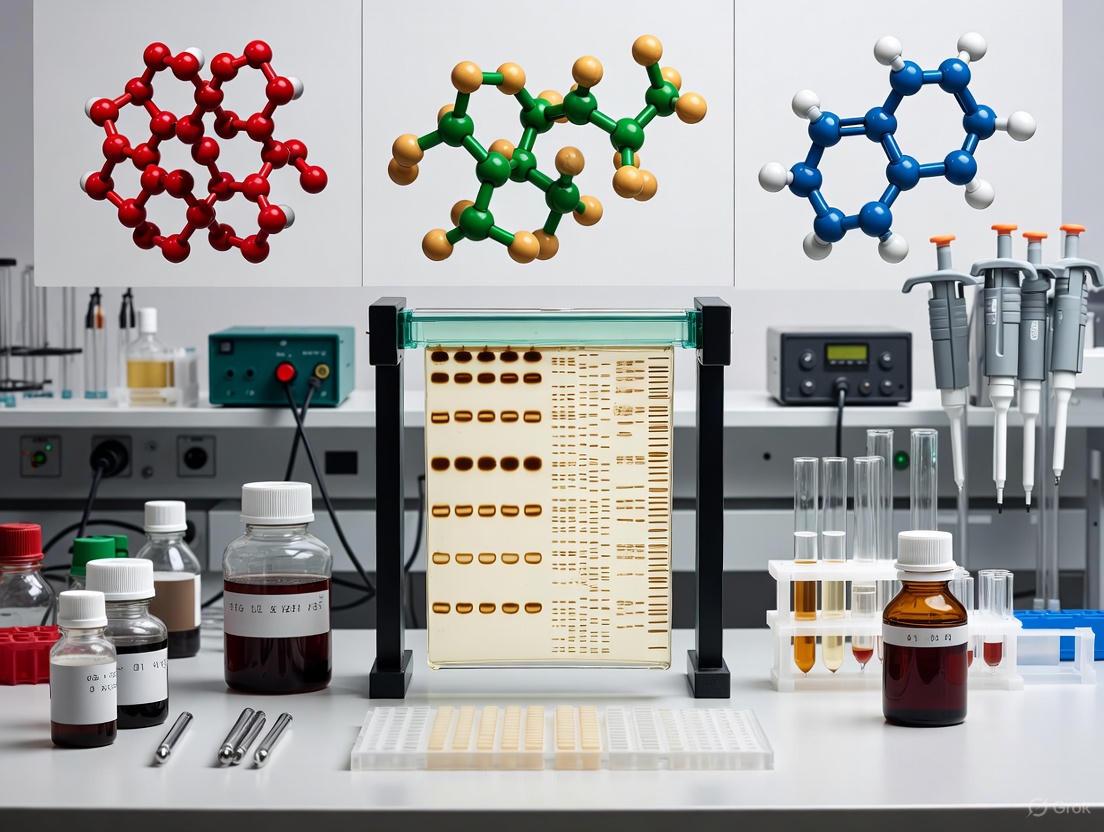

Diagram 1: Conformation Impact on Gel Migration

This diagram illustrates how protein and nucleic acid structural features influence electrophoretic migration through multiple mechanisms, leading to discrepancies between calculated and observed molecular weights.

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin Chain Resolution Workflow

This workflow outlines the key steps for optimizing ubiquitin chain resolution, emphasizing critical decision points for gel and buffer selection based on target chain length.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Reagents for Conformation Studies

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | DUB inhibitor; alkylates active site cysteine residues | Preferred for mass spectrometry applications; use at 20-50 mM in lysis buffer [8] |

| Iodoacetamide (IAA) | Alternative DUB inhibitor; cysteine alkylator | Light-sensitive; avoid for mass spectrometry due to interference with ubiquitylation site identification [8] |

| MG132 (Proteasome Inhibitor) | Preserves ubiquitylated proteins from degradation | Use during cell treatment prior to lysis; prevents degradation of K48-linked chains [8] |

| MES Running Buffer | Optimizes resolution of small ubiquitin oligomers | Ideal for 2-5 ubiquitin chains; use with appropriate gel percentage [8] |

| MOPS Running Buffer | Enhances separation of long polyubiquitin chains | Superior for chains containing eight or more ubiquitins [8] |

| Tris-acetate Buffer | Broad-range high molecular weight separation | Effective for proteins in 40-400 kDa range; suitable for mixed-length samples [8] |

| High-Sieving Agarose | Separates small DNA fragments (20-800 bp) | Comparable to polyacrylamide gels for nucleic acids [14] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Western Blot Analysis of Ubiquitin Chains

Problem: Multiple bands or smearing when probing for ubiquitinated proteins

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple bands at higher molecular weights than expected | Post-translational modifications (PTMs) like glycosylation, SUMOylation, or phosphorylation [15] | Consult resources like PhosphoSitePlus for known PTMs; Treat samples with specific enzymes (e.g., PNGase F for glycosylation) to confirm [15] |

| General smearing across lanes | Protein degradation due to protease activity in the lysate [15] | Use fresh samples and add protease inhibitors (e.g., leupeptin, PMSF, or commercial cocktails) to lysis buffer immediately [15] |

| High background, nonspecific bands | Antibody concentration too high or suboptimal blocking [15] [16] | Titrate down primary/secondary antibody concentration; Ensure compatible blocking buffer (e.g., avoid milk with biotin-avidin systems) [16] |

| Weak or no signal for specific linkage | Epitope masking due to denaturation in SDS-PAGE [17] | Consider linkage-specific TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) that recognize structural epitopes instead of traditional antibodies [4] |

Problem: Viscous samples and irregular lane profiles during SDS-PAGE

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Streaking, wavy lanes, or dumbbell-shaped bands | Genomic DNA contamination [16] | Shear DNA by sonication (e.g., 3 x 10-second bursts with a microtip probe) or pass lysate through a fine-gauge needle [15] [16] |

| Lane widening and significant streaking | High detergent concentration (e.g., from RIPA buffer) or high salt content [16] | Dilute samples before loading; Ensure SDS to nonionic detergent ratio is at least 10:1; Dialyze samples if salt concentration exceeds 100 mM [16] |

Experimental Workflow for Linkage Determination

Problem: Unable to determine ubiquitin chain linkage type

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconclusive data from ubiquitin mutant experiments | Heterotypic or branched chains with multiple linkage types [18] | Perform sequential analysis with K-to-R and K-Only ubiquitin mutants; Use complimentary methods like TUBE-based capture or mass spectrometry [18] [4] [17] |

| Rapid deubiquitination during analysis | DUB activity in cell lysates degrading chains during pulldown [19] | Include deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors like N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) or chloroacetamide (CAA) in lysis and binding buffers [19] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my K48- and K63-linked ubiquitin chains sometimes show different migration patterns on the same gel?

The three-dimensional structure of different ubiquitin chain types can cause anomalies in their migration through SDS-PAGE gels. K48-linked chains adopt a compact, closed conformation, while K63-linked and linear chains form more open, extended structures [17]. These structural differences affect how the SDS detergent binds and how the chains migrate through the gel matrix, leading to apparent molecular weights that may not match their theoretical mass. Using ubiquitin chain standards of known linkage and length alongside your samples is crucial for accurate interpretation.

Q2: My ubiquitin blot shows a smear rather than discrete bands. What does this indicate and how can I fix it?

Smearing typically indicates either protein degradation or heterogeneous ubiquitination. First, rule out degradation by:

- Using fresh protease inhibitor cocktails in your lysis buffer [15]

- Preparing fresh samples and avoiding repeated freeze-thaw cycles [15]

- Keeping samples on ice throughout processing If degradation isn't the issue, the smear may represent authentic heterogeneous ubiquitination, containing chains of different lengths, linkage types, or branched architectures [19] [17]. To resolve discrete bands, optimize your gel percentage - lower percentages (e.g., 8-10%) better resolve longer chains, while higher percentages (12-15%) improve separation of shorter chains.

Q3: How does chain length affect the migration and function of different ubiquitin linkage types?

Chain length significantly impacts both migration and function. For K48-linked chains, Ub3 represents the minimal efficient proteasomal degradation signal, with Ub4 and longer chains triggering even faster degradation [20]. K63-linked chains of different lengths may be preferentially recognized by specific binding proteins; for instance, some autophagy receptors show preference for longer K63 chains [19]. In SDS-PAGE, longer chains of all linkage types will migrate higher, but the relationship between chain length and migration isn't always linear due to structural effects.

Q4: What are branched ubiquitin chains and why are they important?

Branched ubiquitin chains contain a branchpoint where a single ubiquitin molecule is connected to two or more other ubiquitins via different lysine residues. K48/K63-branched chains are particularly significant as they make up approximately 20% of all K63 linkages in cells and can function as superior degradation signals compared to homotypic chains [19] [20]. When analyzing branched chains, it's important to note that the substrate-anchored chain identity primarily determines the degradation fate rather than the branchpoint configuration [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Reagents for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), Chloroacetamide (CAA) [19] | Prevent chain disassembly during analysis; NEM is more potent but has higher risk of off-target effects [19] |

| Linkage-Specific Binding Tools | TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities), linkage-specific antibodies [4] [17] | K48- and K63-TUBEs can selectively enrich respective chains from cell lysates; Antibodies may lose sensitivity for denatured chains [4] |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K-to-R (Lysine-to-Arginine) mutants, K-Only mutants [18] | K-to-R mutants prevent chain formation through specific lysines; K-Only mutants restrict linkage to a single lysine type for verification [18] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, Leupeptin, Commercial cocktails [15] [16] | Essential for preventing protein degradation during sample preparation; Use broad-spectrum cocktails for optimal protection [15] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Determining Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Using Ubiquitin Mutants

This protocol uses in vitro ubiquitination reactions with mutant ubiquitins to determine chain linkage composition [18].

Materials:

- E1 Enzyme (5 µM)

- E2 Enzyme (25 µM) - choose based on E3 compatibility

- E3 Ligase (10 µM)

- Wild-type Ubiquitin (1.17 mM)

- Ubiquitin K-to-R Mutant set (K6R, K11R, K27R, K29R, K33R, K48R, K63R; 1.17 mM each)

- Ubiquitin K-Only Mutant set (each containing only one lysine; 1.17 mM each)

- 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer (500 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM TCEP)

- MgATP Solution (100 mM)

- Your protein substrate of interest

Procedure:

Set up K-to-R mutant reactions (25 µL volume for each):

- Prepare separate reactions for wild-type ubiquitin and each of the seven K-to-R mutants

- Use identical components except for the ubiquitin variant:

- 2.5 µL 10X E3 Reaction Buffer

- 1 µL Ubiquitin or Ubiquitin mutant (~100 µM final)

- 2.5 µL MgATP Solution (10 mM final)

- Your substrate (5-10 µM final)

- 0.5 µL E1 Enzyme (100 nM final)

- 1 µL E2 Enzyme (1 µM final)

- X µL E3 Ligase (1 µM final)

- dH₂O to 25 µL

Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes

Terminate reactions with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (for western blotting) or EDTA/DTT (for downstream applications)

Analyze by western blot using anti-ubiquitin antibody

- The reaction with the K-to-R mutant that lacks the required lysine will show only mono-ubiquitination

- Other reactions will show polyubiquitination

Verify with K-Only mutants by repeating steps 1-4 with the K-Only mutant set

- Only wild-type ubiquitin and the K-Only mutant with the correct linkage lysine will form polyubiquitin chains

Workflow for Investigating Linkage-Specific Migration Anomalies

Functional Properties of Ubiquitin Chain Types

| Chain Type | Key Functional Associations | Minimal Degradation Signal | Specialized Binders / Regulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [4] [20] | K48-Ub3 [20] | RAD23B (shuttling factor), UCH37 (K48-specific DUB) [19] [21] |

| K63-linked | NF-κB signaling, autophagy, protein trafficking [19] [4] | Generally non-degradative [4] [20] | EPN2 (endocytosis adaptor), TAK1/TAB complex (signaling) [19] [4] |

| K48/K63-branched | Enhanced degradation in specific contexts [19] [20] | Substrate-anchored chain dependent [20] | PARP10, UBR4, HIP1 (branch-specific binders) [19] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Ubiquitin Linkage Determination Troubleshooting

Problem: Inconclusive results when determining ubiquitin chain linkage using ubiquitin mutants.

| Problem & Observation | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No chain formation with any Ubiquitin K-to-R mutant in initial screen. | - E1/E2/E3 enzyme inactivity- Incorrect reaction buffer conditions- ATP degradation | - Confirm enzyme activity with wild-type ubiquitin control.- Ensure fresh MgATP is used and 10 mM final concentration in reaction [18]. |

| Chain formation persists with all Ubiquitin K-to-R mutants. | - Met1 (linear) linkage formation- Heterotypic/mixed linkage chains | - Perform linkage verification with Ubiquitin "K-Only" mutants [18].- Suspect mixed linkages if some K-to-R mutants show reduced (not absent) chain formation [18]. |

| High background or non-specific bands on Western blot. | - Antibody non-specificity- Sample degradation | - Include a negative control reaction without MgATP [18].- Use fresh protease inhibitors and optimize antibody dilution. |

| Faint or no bands in verification with Ubiquitin "K-Only" mutants. | - Low efficiency of chain formation with restricted lysines- Suboptimal E2/E3 pair for specific linkage | - Increase reaction incubation time to 60 minutes [18].- Verify E2 enzyme specificity for the suspected linkage [5]. |

Gel Electrophoresis Analysis of Ubiquitinated Proteins

Problem: Smeared or poorly resolved bands when analyzing polyubiquitinated proteins by SDS-PAGE.

| Problem & Observation | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smeared bands across lanes. | - Sample overloading- Protein degradation by proteases- Incomplete denaturation | - Load 0.1–0.2 µg of protein per mm of gel well width [13].- Use fresh protease inhibitor cocktails [22].- Ensure sample is heated with SDS-containing loading dye. |

| Bands appear fuzzy and poorly separated. | - Gel percentage not optimal for ubiquitin chain size- Voltage or run time suboptimal | - Use higher percentage polyacrylamide gels to resolve smaller fragments and shorter chains [13].- Apply recommended voltage for the gel type and buffer system. |

| Bands are only visible in some lanes. | - Uneven staining- Well distortion during loading | - For in-gel staining, ensure stain is thoroughly mixed in gel solution [13].- Pipette carefully to avoid damaging wells [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I be concerned about branched ubiquitin chains when studying proteasomal degradation?

Branched ubiquitin chains are not simply a sum of their homotypic parts; they can constitute distinct, high-priority degradation signals. Specifically, K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains are recognized as a potent signal for proteasomal degradation, fast-tracking substrate turnover during critical processes like cell cycle progression and proteotoxic stress [5]. The proteasome has evolved a multivalent recognition mechanism, using specific receptors like RPN2 to simultaneously engage different linkages within a branched chain, making them more efficient degradation signals than homotypic K48 chains alone [5].

Q2: My experiment suggests the presence of heterotypic ubiquitin chains. How can I confirm if they are mixed versus branched?

Distinguishing mixed from branched chains requires techniques that can identify a ubiquitin molecule modified at more than one lysine residue—the defining feature of a branch point [23].

- Advanced Mass Spectrometry (MS): Methods like isotopically resolved mass spectrometry of peptides (IRMSP) can directly monitor the conjugation site of new ubiquitin molecules on a pre-existing chain, identifying branched structures [24].

- Ubiquitin Chain Restriction (Lbpro* Clipping): This method, combined with intact protein MS, can reveal doubly ubiquitinated ubiquitin, which is clear evidence of branching [5].

- Linkage-Specific Antibodies & Enzymes: Using a combination of linkage-specific DUBs (e.g., UCHL5 for K11/K48-branched chains [5]) and antibodies in cleavage assays can provide indirect evidence of chain architecture.

Q3: What are the key experimental controls for in vivo ubiquitination assays?

For reliable in vivo ubiquitination data (e.g., co-transfecting His-Ub and substrate plasmids [22]), include these critical controls:

- Proteasome Inhibition: Use MG-132 to prevent degradation of ubiquitinated substrates, allowing for their accumulation and detection [22].

- Catalytic Mutants: Include catalytically dead mutants of your E3 ligase (e.g., cysteine mutant for HECT/RBR E3s) to demonstrate that ubiquitination is dependent on the E3's activity.

- Lysine Mutants of Substrate: Mutate the target lysine(s) on your substrate protein to confirm the specificity of ubiquitination [22].

Q4: How does the cleavage mechanism of a Deubiquitinase (DUB) affect the interpretation of my ubiquitination data?

The cleavage mechanism (endo-, exo-, or base-cleavage) of a DUB directly influences the ubiquitin chain landscape on a substrate [25]. For example, USP1/UAF1 processes K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains on PCNA via exo-cleavage. This means it trims the chain from the distal end, one ubiquitin at a time. This can lead to a temporary enrichment of monoubiquitinated PCNA even as polyubiquitinated forms are being processed [25]. If you only observe the monoubiquitinated form, you might misinterpret it as the primary signal, when it could be a transient intermediate of polyubiquitin chain disassembly.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Determining Ubiquitin Chain Linkage In Vitro

This protocol uses ubiquitin lysine mutants to identify the specific lysine linkage(s) in a homotypic or heterotypic chain [18].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Ubiquitin K-to-R Mutants | Each mutant (K6R, K11R, etc.) lacks a single lysine. Absence of chain formation with one mutant identifies the essential linkage [18]. |

| Ubiquitin "K-Only" Mutants | Each mutant has only one lysine (e.g., K6-only). Chain formation only with the relevant "K-Only" mutant verifies the linkage [18]. |

| E1 Activating Enzyme | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, initiating the enzymatic cascade for all reactions [18]. |

| E2 Conjugating Enzyme | Determines the inherent linkage specificity for the ubiquitin chain being built [5]. |

| E3 Ligase | Provides substrate specificity and works with the E2 to build the chain [18]. |

| MgATP Solution | Essential energy source for the E1-mediated activation step [18]. |

Methodology:

- Initial Screen with K-to-R Mutants:

- Set up nine separate 25 µL reactions, each containing [18]:

- 1X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP)

- ~100 µM of wild-type ubiquitin or a specific Ubiquitin K-to-R mutant

- 10 mM MgATP

- Your substrate (5-10 µM)

- E1 Enzyme (100 nM)

- E2 Enzyme (1 µM)

- E3 Ligase (1 µM)

- Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Terminate reactions with SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Analyze by Western blot using an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

- Interpretation: The reaction that fails to form polyubiquitin chains (showing only monoubiquitination) indicates the linkage type. For example, if the K48R mutant shows no chains, the linkage is K48 [18].

- Set up nine separate 25 µL reactions, each containing [18]:

- Verification with "K-Only" Mutants:

- Repeat the above setup using Ubiquitin "K-Only" mutants.

- Interpretation: Only the wild-type ubiquitin and the "K-Only" mutant corresponding to the linkage (e.g., K48-only) will support robust chain formation, confirming the result [18].

Advanced Technique: Monitoring Branched Ubiquitin Chain Assembly

The isotopically resolved mass spectrometry of peptides (IRMSP) technique allows for monitoring the real-time assembly of complex ubiquitin chains, including branched architectures, with minimal perturbation to the enzyme/substrate system [24].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Analysis of Ubiquitin Chains

Table 1: Quantitative Linkage Analysis of a Heterotypic Ubiquitin Chain Sample

This table exemplifies data obtained from mass spectrometry-based ubiquitin absolute quantification (Ub-AQUA), a technique used to determine the precise composition of ubiquitin chains in a sample [5].

| Ubiquitin Linkage Type | Relative Abundance (%) | Notes / Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | ~47% | Canonical degradation signal; one component of the major branched chain [5]. |

| K11-linked | ~47% | Often works with K48 in branched chains to form a potent degradation signal [5]. |

| K33-linked | ~6% (Minor) | Minor component; function may be context-dependent [5]. |

| K63-linked | Not Detected | Confirms the engineered E3 ligase (Rsp5-HECT^GML^) did not produce this linkage [5]. |

Table 2: Degradation Efficiency of Substrates with Different Ubiquitin Chain Architectures

This table summarizes findings from UbiREAD technology, which compares the intracellular degradation rates of a model substrate (GFP) modified with defined ubiquitin chains [26].

| Ubiquitin Chain Architecture | Degradation Outcome | Half-Life / Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| K48-Ub3 (Homotypic) | Rapid Degradation | A minimal, sufficient proteasomal targeting signal [26]. |

| K63-Ub (Homotypic) | Rapid Deubiquitination | Not degraded; quickly removed by DUBs [26]. |

| K48/K63-Branched | Degradation | Substrate-anchored chain identity dictates fate; not a simple sum of parts [26]. |

| K11/K48-Branched | Priority Degradation | Fast-tracking of substrate turnover [5]. |

Methodological Guide: Selecting Gel Percentage and Buffer for Sharp Ubiquitin Band Resolution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do my ubiquitinated proteins appear as a high molecular weight "smear" on my western blot?

The characteristic smear is due to several factors inherent to ubiquitination. Proteins can be modified by a heterogeneous number of ubiquitin molecules (each adding ~8.5 kDa), leading to a ladder of different molecular weights rather than discrete bands. Furthermore, even chains of identical length can run at different positions on denaturing SDS-PAGE gels because ubiquitin does not fully unfold, and its migration is influenced by the specific linkage type that defines the chain's three-dimensional structure [27] [28]. This is compounded by the fact that a protein may be ubiquitinated at multiple distinct lysine residues [27].

FAQ 2: How does the polyacrylamide gel percentage affect the resolution of different ubiquitin chain lengths?

The percentage of your gel creates a pore size matrix that dictates the resolution range for protein separation. Lower percentage gels (e.g., 4-8%) are optimal for resolving high molecular weight proteins and long ubiquitin chains, while higher percentage gels (e.g., 12%) provide better separation for smaller proteins and short ubiquitin chains [8] [29]. The table below summarizes the recommended gel percentages for resolving different ubiquitin chain lengths.

Table 1: Gel Percentage Selection Guide for Ubiquitin Chain Resolution

| Target Ubiquitin Chain Length | Recommended Gel Percentage | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Di- to Pentamer (2-5 Ub) | 10-12% | Provides superior resolution for shorter chains and monoubiquitination. |

| Mixed Lengths (2-20+ Ub) | 8% (single percentage) | A good all-rounder for separating chains up to 20 ubiquitin units [29]. |

| Mixed Lengths (2-20+ Ub) | 4-12% (gradient) | Gradient gels offer the broadest resolution range across different chain lengths. |

| Long Chains (>8 Ub) | 4-8% | Optimized for resolving very long polyubiquitin chains. |

FAQ 3: My gel percentage is correct, but my resolution is still poor. What other factors should I optimize?

The buffer system used for gel electrophoresis significantly impacts the resolution and apparent mobility of ubiquitin chains due to their unique conformation [8]. Selecting the appropriate running buffer is crucial for fine-tuning separation.

Table 2: Running Buffer Selection for Optimized Ubiquitin Chain Resolution

| Running Buffer | Optimal Resolution Range | Typical Gel Type |

|---|---|---|

| MES (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid) | Di- to Pentamer (2-5 ubiquitins) | Pre-casted gels [8] |

| MOPS (3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid) | Long chains (8+ ubiquitins) | Pre-casted gels [8] [29] |

| Tris-Glycine | Broad range (up to 20+ ubiquitins) | 8% single-percentage gels [8] [29] |

| Tris-Acetate | Proteins 40-400 kDa | Ideal for large ubiquitinated substrates [8] |

Experimental Protocol: UbiCRest for Linkage Type Determination

The UbiCRest protocol is a qualitative method used to identify the types of ubiquitin linkages present in a sample by exploiting the linkage-specificity of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [27].

- Sample Preparation: Generate your ubiquitinated protein sample. It is critical to preserve the ubiquitination state by including high concentrations of DUB inhibitors (e.g., 50-100 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and 5-10 mM iodoacetamide (IAA)) in the lysis buffer to prevent chain degradation by endogenous DUBs [8] [29].

- DUB Panel Setup: Set up parallel reactions, each containing your ubiquitinated sample and a different, linkage-specific DUB. A typical panel may include:

- USP21 or USP2 (1-5 µM): Positive control; cleaves all linkage types.

- Cezanne (0.1-2 µM): Specific for K11-linked chains.

- OTUB1 (1-20 µM): Highly specific for K48-linked chains.

- OTUD1 (0.1-2 µM): Specific for K63-linked chains [27].

- Incubation: Incubate the reactions at 37°C for 1-2 hours.

- Analysis: Stop the reactions with SDS sample buffer and analyze the products by western blotting. The cleavage pattern reveals the linkage types present. For example, if a sample is treated with OTUB1 and the ubiquitin smear disappears, it indicates the chains were predominantly K48-linked [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DUB Inhibitors (NEM, IAA) | Preserves ubiquitination state during lysis by alkylating active-site cysteines of DUBs. | NEM is preferred for MS work; IAA is light-sensitive. Use high concentrations (up to 100 mM) for K63/M1 chains [8] [29]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitor (MG132) | Prevents degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, aiding their detection. | Can induce cellular stress responses during prolonged treatments (>12h) [8] [29]. |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | Enzymatic tools for deciphering ubiquitin chain linkage type (UbiCRest). | Must be profiled for specificity; working concentrations vary (e.g., OTUB1: 1-20 µM; Cezanne: 0.1-2 µM) [27]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Immunoblotting detection of specific ubiquitin chain types (e.g., K48, K63). | Not all antibodies recognize all linkages equally; validation is crucial. Antibodies for M1, K27, K29 are less common [29]. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Affinity enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates. | Act as potent DUB inhibitors and protect chains from proteasomal degradation during pull-down [8] [30]. |

Optimizing Buffer Systems for Denaturation and Charge Uniformity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is buffer selection critical for resolving different ubiquitin chain types? Buffer composition directly impacts the stability, charge, and migration of ubiquitinated proteins during electrophoresis. Different ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48, K63, K11/K48-branched) have distinct structural properties and functions. K48-linked chains primarily target proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains regulate signal transduction and protein trafficking [4]. Proper buffer conditions are essential to maintain the structural integrity of these chains during analysis and prevent artifacts that could lead to misinterpretation.

FAQ 2: How does pH affect the analysis of ubiquitinated proteins? The pH of the buffer solution influences the surface charge of a protein, which in turn affects its solubility and propensity to aggregate. Antibodies and many other biologics often demonstrate better colloidal stability at lower pH, but for biologically-relevant studies, formulation at or near physiological pH (7.35-7.45) is often necessary. The buffering component must be chosen so that its pKa is within ±1 pH unit of the desired working pH [31]. Common buffers include Tris (pKa=8.1), phosphate buffered saline (often pH 7.4), and histidine (pKa=6.01) [31].

FAQ 3: What are the consequences of protein adsorption in electrophoretic systems? Protein adsorption to capillary or channel walls in electrophoretic systems causes contamination of the surface, leading to uneven potential distribution during separation. This results in peak asymmetry, band broadening, reduced resolution, shorter migration times, lower detection response, and poor reproducibility [32]. This is a particular challenge with ubiquitinated proteins due to their heterogeneous nature.

FAQ 4: How can I prevent aggregation of protein samples during storage and analysis? Beyond optimizing pH and salt concentrations, adding excipients such as surfactants, polyols, sugars, and amino acids can help prevent protein aggregation and denaturation [31]. Additionally, understanding and mitigating stress factors during freeze-thaw cycles is crucial, as cold denaturation and shear stress from ice crystal formation can promote aggregation [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Resolution of Ubiquitin Chain Types

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Gel Percentage: Use higher percentage gels to better separate shorter chains and lower percentages for longer, branched chains.

- Suboptimal Buffer pH: The buffer pH must be optimized to maximize charge differences between different ubiquitin chain types. Test different buffers within their effective range (pKa ±1).

- Insufficient Denaturation: Ensure complete denaturation of samples to break non-covalent interactions that might cause aberrant migration.

- Sample Degradation: Use fresh protease inhibitors and work quickly on ice to prevent deubiquitinase activity from degrading chains.

Experimental Protocol: Buffer pH Optimization for Chain Separation

- Objective: Determine the optimal pH for resolving K48 vs. K63 ubiquitin chains.

- Materials: Pre-formed K48-Ub4 and K63-Ub4 chains (commercial or synthesized [20]), a range of buffers (e.g., MES for pH 6.0-7.0, PBS for ~7.4, Tris for 7.5-9.0), standard SDS-PAGE equipment.

- Method:

- Prepare identical samples of a K48/K63 chain mixture.

- Denature each sample in Laemmli buffer prepared with the different test buffers.

- Run all samples on the same high-percentage (e.g., 15%) SDS-PAGE gel.

- Perform Western blotting with linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-K48-Ub, anti-K63-Ub) [4].

- Analysis: The pH condition that provides the sharpest, most distinct bands with the greatest separation between linkage types is optimal.

Problem 2: Excessive Smearing or Streaking on the Gel

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Protein Aggregation: Optimize buffer components to improve colloidal stability. Add excipients and ensure proper salt concentration to shield attractive forces between protein molecules [31].

- Non-specific Protein Adsorption: Treat capillary or gel apparatus surfaces with passivating agents. For example, coat surfaces with hydrophilic polymers like PEG to prevent non-specific adsorption [32].

- Overloading of Sample: Reduce the amount of total protein loaded on the gel. Ubiquitination signals can be strong even with a small amount of material.

- Incomplete Denaturation: Ensure the sample buffer contains fresh SDS and reducing agent, and that the boiling step is performed adequately.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing and Mitigating Aggregation

- Objective: Identify if sample aggregation is causing smearing and test mitigation strategies.

- Materials: Protein sample, dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument or microflow imaging, potential excipients (e.g., sucrose, arginine, non-ionic detergents).

- Method:

- Analyze the sample using DLS to check for the presence of large, soluble aggregates.

- Divide the sample and incubate with different excipients.

- Re-analyze with DLS after incubation.

- Run treated and untreated samples on a gel.

- Analysis: The condition that reduces the size and population of aggregates in DLS and minimizes smearing on the gel is the most effective.

Problem 3: Low Signal from Ubiquitinated Proteins

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inefficient Transfer during Western Blotting: Optimize transfer conditions. Use pre-stained markers to confirm efficient transfer of proteins of the expected size.

- Poor Antibody Affinity: Validate antibodies using known controls (e.g., cells treated with L18-MDP for K63 chains [4] or specific PROTACs for K48 chains [4]). Consider using Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) to enrich for ubiquitinated proteins before blotting [4].

- Instability of Ubiquitin Chains: Include deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors in your lysis and sample buffers to prevent chain degradation. Work quickly and keep samples cold.

Problem 4: Inconsistent Results Between Runs

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Buffer Degradation: Prepare fresh electrophoresis and transfer buffers for each run.

- Variable Salt Concentrations: High salt can cause band distortion and heating. Desalt samples if necessary or ensure consistent ionic strength.

- Joule Heating: Use a constant voltage and ensure adequate cooling during electrophoresis. Microfluidic systems are particularly susceptible to Joule heating, which can cause band broadening and loss of resolution [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Reagents for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chain-specific TUBEs | High-affinity enrichment of linkage-specific polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates. | K48- or K63-specific TUBEs; used to investigate context-dependent ubiquitination [4]. |

| Linkage-specific Antibodies | Detection of specific ubiquitin chain linkages via Western blotting or immunofluorescence. | Anti-K48-Ub, Anti-K63-Ub; essential for validating chain identity [4] [5]. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Prevents the cleavage of ubiquitin chains during sample preparation, preserving the ubiquitination signal. | Include in lysis buffers (e.g., PR-619, N-ethylmaleimide). |

| PROTACs/Molecular Glues | Induce targeted K48-linked ubiquitination and degradation of specific proteins of interest. | RIPK2 PROTAC; used as a tool to study K48 ubiquitination [4]. |

| Inflammatory Agonists | Stimulate non-degradative ubiquitination signaling pathways (e.g., K63-linked). | L18-MDP; activates NOD2/RIPK2 pathway, inducing K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2 [4]. |

| Defined Ubiquitinated Reporters | Bespoke substrates for studying degradation kinetics and deubiquitination of specific chain types. | K48-Ub4-GFP, K63-Ub4-GFP; used in the UbiREAD platform for high-resolution kinetic studies [20]. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Ubiquitin Analysis Workflow

K63 Ubiquitin Signaling Pathway

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Using TUBEs for Linkage-Specific Enrichment [4] This protocol is used to capture and study endogenous ubiquitination events, such as those on RIPK2.

- Cell Stimulation: Treat cells (e.g., THP-1) with an inflammatory agent like L18-MDP (200-500 ng/ml for 30-60 min) to stimulate K63 ubiquitination, or a PROTAC to induce K48 ubiquitination.

- Lysis: Lyse cells in a specialized buffer designed to preserve polyubiquitination.

- Enrichment: Incubate the cell lysate with magnetic beads conjugated to chain-specific TUBEs (e.g., K63-TUBE, K48-TUBE, or pan-TUBE).

- Wash and Elute: Wash beads thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins.

- Analysis: Detect the eluted proteins by Western blotting using an antibody against the protein of interest (e.g., anti-RIPK2).

Protocol 2: UbiREAD for Degradation Kinetics [20] This method involves delivering pre-formed, defined ubiquitinated substrates into cells to precisely measure degradation kinetics.

- Substrate Synthesis: Synthesize a model substrate (e.g., GFP) conjugated to a defined ubiquitin chain (e.g., K48-Ub4) using recombinant methods.

- Intracellular Delivery: Deliver the ubiquitinated substrate into mammalian cells (e.g., RPE-1, THP-1) via electroporation.

- Fixation and Harvest: At various time points (e.g., 20 seconds to 20 minutes), rapidly fix cells for flow cytometry or harvest them using ice-cold buffers to slow reactions.

- Analysis: Analyze the loss of GFP fluorescence over time by flow cytometry or in-gel fluorescence to monitor degradation and the appearance of deubiquitinated species. This allows calculation of degradation half-lives.

A Step-by-Step Protocol from Cell Lysis to Electrophoresis

The ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates critical cellular processes, and understanding it requires precise analysis of ubiquitin chains. This protocol provides a detailed methodology from cell lysis through electrophoresis, specifically optimized for resolving diverse ubiquitin chain architectures. Proper technique is essential as different ubiquitin linkages control distinct biological outcomes—K48-linked chains primarily target proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains regulate signaling and trafficking [4] [34]. The recommendations below incorporate current research to address common challenges in ubiquitin biochemistry.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Sample Preparation

FAQ: Why are my ubiquitin signals weak or inconsistent?

This typically results from incomplete inhibition of deubiquitinases (DUBs) or proteasomal activity during sample preparation.

- Solution: Add fresh protease inhibitors to your lysis buffer immediately before use [35]. Specifically include deubiquitinase inhibitors like N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) at 5-10 mM, noting that for K63 linkages, concentrations up to 10 times higher may be necessary for proper preservation [29]. Additionally, include proteasome inhibitors such as MG132 to prevent degradation of ubiquitinated proteins [29]. Avoid prolonged MG132 treatment (over 12-24 hours) as it can induce cellular stress and aberrant ubiquitin chain formation [29].

FAQ: Which lysis buffer should I use?

The optimal buffer depends on your experimental goals and whether you need to preserve protein complexes.

- Solution: Select a buffer based on your downstream applications:

Table 1: Lysis Buffer Selection Guide

| Buffer Type | Best For | Composition Example | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIPA [35] | Standard western blotting, total protein extraction | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS [35] | Effective for membrane disruption; may disrupt weak protein interactions. |

| Specialized Lysis Buffer [35] | Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP), preserving protein complexes | 50 mM HEPES/KOH (pH 7.5), 250 mM Sorbitol, 5 mM Mg-Acetate, 0.5 mM EGTA [35] | Gentler detergents; helps maintain native protein interactions. |

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting

FAQ: How do I achieve optimal separation of different ubiquitin chain lengths?

Ubiquitinated proteins form a ladder pattern, with each ubiquitin adding ~8 kDa [29]. Poor separation makes it difficult to resolve individual chains.

- Solution: Optimize your gel percentage and running buffer based on the chain sizes you wish to resolve.

Table 2: Gel and Buffer Optimization for Ubiquitin Chain Resolution

| Target Ubiquitin Chains | Recommended Gel Percentage | Recommended Running Buffer | Expected Separation Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long chains (>8 ubiquitin units) [29] | 8% gel [29] | MOPS buffer [29] | Best for high molecular weight smears |

| Shorter chains (2-5 ubiquitin units) [29] | 12% gel [29] | MES buffer [29] | Improved resolution for lower molecular weight ladders |

| General purpose / mixed lengths [29] | 8% gel with Tris-Glycine buffer [29] | Tris-Glycine [29] | Good separation across a wide range |

FAQ: Why is my western blot transfer inefficient for high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins?

Long ubiquitin chains can unfold or transfer poorly with standard protocols.

- Solution: Use PVDF membranes for higher signal strength compared to nitrocellulose [29]. For a 0.2 µm pore size PVDF membrane, perform a wet transfer at 30 V for 2.5 hours instead of faster methods to ensure complete transfer of large ubiquitin complexes [29].

FAQ: How can I validate antibody specificity for different ubiquitin linkages?

Many commercial ubiquitin antibodies have varying affinities for different chain types.

- Solution: Be aware that linkage-specific antibodies are available for K6, K11, K33, K48, and K63 chains, but may have varying recognition efficiency [29]. Some general anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., from Dako or Cell Signaling Technology) do not recognize all linkage types equally [29]. Always report the specific antibody used in your methods. As an alternative, consider using specific ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) for pull-down experiments or as probes [29].

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram summarizes the key steps in the optimized protocol for detecting protein ubiquitination, from cell culture to analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Usage & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) [29] | Deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitor | Preserve ubiquitin signals during lysis; use 5-10 mM, or higher for K63 chains [29]. |

| MG132 [22] [29] | Proteasome inhibitor | Prevent degradation of ubiquitinated substrates; avoid prolonged use >24h [29]. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) [4] | High-affinity ubiquitin chain enrichment | Capture endogenous polyubiquitinated proteins from lysates with minimal chain disassembly [4]. |

| Linkage-specific DUBs (e.g., OTUB1, AMSH) [34] | Ubiquitin chain linkage validation | Confirm chain topology via enzymatic disassembly in UbiCRest assays [34]. |

| Engineered DUBs (enDUBs) [36] | Live-cell linkage editing | Study functions of specific ubiquitin chains on GFP-tagged proteins in live cells [36]. |

| His-Ubiquitin Plasmids [22] | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins | Express His-tagged Ub in cells for pull-down under denaturing conditions using Ni-NTA beads [22]. |

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology. The ubiquitin code's complexity arises from the ability to form at least 12 different chain linkage types, each with distinct structural and functional consequences [37]. Among these, K48-linked chains are primarily associated with proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains typically regulate signal transduction, protein trafficking, and inflammatory pathways [4]. Recent research has also revealed the importance of branched ubiquitin chains, where a single ubiquitin molecule is modified at multiple sites, creating complex topological structures that can function as priority degradation signals [5] [37].

The resolution of this complex ubiquitin signaling is essential for understanding cellular homeostasis and developing targeted therapies. Within this context, UbiCRest (Ubiquitin Chain Restriction) analysis serves as a powerful method for deciphering linkage-specific ubiquitination patterns using linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs) to cleave and identify ubiquitin chain types present on substrates.

Key Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Ubiquitin Enrichment

Protocol: TUBE-Based Ubiquitin Enrichment for Subsequent UbiCRest Analysis

Principle: Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) are engineered high-affinity ubiquitin-binding molecules that protect polyubiquitin chains from deubiquitinases and the proteasome during cell lysis [4]. Chain-specific TUBEs can selectively capture particular ubiquitin linkage types.

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in a buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, plus protease and DUB inhibitors). Maintain samples at 4°C throughout.

- Enrichment: Incubate cell lysates (50-100 µg total protein) with chain-specific TUBE-conjugated beads (e.g., K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, or Pan-TUBE) for 2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation [4].

- Washing: Wash beads extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute ubiquitinated proteins with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing DTT for subsequent western blotting or with high-pH buffer (e.g., 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate) for mass spectrometry analysis.

Troubleshooting Note: Include control samples treated with DUB inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide) to prevent artificial deubiquitination during sample processing.

UbiCRest Analysis Workflow

Protocol: Linkage-Specific Deubiquitination Assay

Principle: This method uses purified DUBs with known linkage specificities to digest ubiquitin chains from an immunoprecipitated substrate of interest. The resulting cleavage pattern reveals the chain types present.

Procedure:

- Immunoprecipitation: Immunoprecipitate your target protein from cell lysates using specific antibodies and protein A/G beads.

- DUB Reaction Setup: Split the beads into several aliquots. To each aliquot, add 1-2 µg of a specific purified DUB in an appropriate reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT).

- DUB Panel: Essential controls and DUBs include:

- No DUB control: Incubated with buffer alone.

- USP2 (or another promiscuous DUB): Cleaves all linkage types; confirms the signal is due to ubiquitination.

- OTUB1: Preferentially cleaves K48-linked chains.

- AMSH or USP53/USP54: Specifically cleaves K63-linked chains [38].

- Cezanne: Specifically cleaves K11-linked chains.

- Incubation: Incubate reactions for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop reactions by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Analyze by western blotting using antibodies against your target protein. A mobility shift or disappearance of higher molecular weight species indicates cleavage of the specific chain type by the corresponding DUB.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: In my UbiCRest assay, all DUBs including the specific ones completely remove the ubiquitin signal. What could be wrong? A: This typically indicates an overdigestion issue. Possible causes and solutions include:

- Cause: Too much DUB enzyme or incubation time too long.

- Solution: Titrate the amount of each DUB (try 0.1-1 µg) and reduce incubation time (30-90 minutes). Include time-course experiments.

- Cause: Suboptimal reaction conditions affecting DUB specificity.

- Solution: Ensure the correct pH and salt concentration in the reaction buffer, as some DUBs require specific conditions for linkage specificity.

Q2: My negative control (no DUB) shows loss of ubiquitin signal similar to my DUB-treated samples. How can I preserve the ubiquitin chains? A: This suggests non-specific deubiquitination during the assay procedure.

- Cause: Contaminating DUBs from the immunoprecipitation or sample processing.

- Solution: Always include fresh DUB inhibitors (e.g., 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide or 5 µM PR-619) in all lysis and wash buffers until the final DUB reaction step. Keep samples on ice whenever possible.

Q3: I am working with an endogenous protein and cannot detect a clear ubiquitin smear by western blot after immunoprecipitation. What are my options? A: Low abundance of endogenous ubiquitinated species is a common challenge.

- Solution 1: Use TUBE-based enrichment (as described in Protocol 2.1) prior to the UbiCRest assay to concentrate ubiquitinated proteins and protect chains from degradation [4].

- Solution 2: Consider a dual approach: enrich with Pan-TUBE to capture all ubiquitinated forms, then perform UbiCRest with chain-specific DUBs on the eluate.

- Solution 3: If possible, treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132, 10 µM for 4-6 hours) prior to lysis to accumulate ubiquitinated substrates.

Q4: How can I distinguish between homotypic K63 chains and branched chains containing K63 linkages? A: This requires a sequential or parallel DUB digestion strategy.

- Approach: First, treat the sample with a K63-specific DUB like USP54, which cleaves within K63-linked chains [38]. If the smear completely collapses, it suggests homotypic K63 chains. If a higher molecular weight smear persists, it indicates the presence of other linkages (possibly in a branched structure). Subsequent treatment with a DUB like USP2 (promiscuous) or Otub1 (K48-specific) can then reveal the nature of the remaining chains.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Reagents for Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain-Specific Binding Reagents | K63-TUBEs / K48-TUBEs [4] | Selective enrichment of linkage-specific ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates. | Nanomolar affinity; protects chains from DUBs; used in HTS assays. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies [39] | Detection of specific chain types by western blot or immunofluorescence. | Varies in specificity and affinity; validation is crucial. | |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | USP53 / USP54 [38] | UbiCRest: Specific cleavage of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains. | High specificity for K63 linkages; USP53 performs en bloc removal. |

| OTUB1 [37] | UbiCRest: Preferentially cleaves K48-linked ubiquitin chains. | Well-characterized K48-linkage preference. | |

| AMSH [37] | UbiCRest: Specific cleavage of K63-linked chains. | Metalloprotease with high specificity for K63 linkages. | |

| Engineered Tools | Ubiquiton [40] | Inducible, linkage-specific polyubiquitylation of target proteins in cells. | Synthetic biology tool for controlled ubiquitination. |

| Ub-POD [41] | Proximity-dependent labeling to identify substrates of specific E3 ligases. | Uses BirA fusion and biotin acceptor peptide fused to Ub. |

Workflow Visualization

Troubleshooting Ubiquitin Gels: Solving Smears, Poor Resolution, and Artifacts

Diagnosing and Eliminating the 'Ubiquitin Smear' in Western Blots

FAQ: Understanding the Ubiquitin Smear

Why does a smear appear when I blot for ubiquitin?

A smear on your western blot is not necessarily a sign of a failed experiment. It is a typical characteristic of samples containing ubiquitinated proteins. This pattern occurs because your protein of interest exists in multiple forms, each modified by ubiquitin chains of different lengths and linkages. Since each ubiquitin monomer adds approximately 8 kDa to the protein's molecular weight, a heterogeneous mixture results in a continuous smear rather than a discrete band [42] [29].

What do the different patterns in the smear mean?

The appearance of the smear can offer clues about the nature of the ubiquitination:

- High-Molecular-Weight Smear: This indicates extensive polyubiquitination of your target protein.

- Ladder Pattern: Sometimes, a ladder of distinct bands may be visible within the smear, with each band corresponding to the target protein with one, two, three, etc., ubiquitin molecules attached. This is more common with in vitro ubiquitination assays [18].

- Lower Smear: A predominant smear at a lower molecular weight might suggest monoubiquitination or multi-monoubiquitination (where multiple lysines on the substrate each receive a single ubiquitin) [42] [29].

Troubleshooting Guide: From Sample to Detection

The following table outlines the core components of a successful experiment to study protein ubiquitination, highlighting common pitfalls and their solutions.

| Troubleshooting Area | Common Pitfalls | Optimized Solutions & Reagent Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Degradation of ubiquitin chains by deubiquitinases (DUBs) during lysis. Loss of signal due to proteasomal degradation. | Use DUB inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide/NEM at 5-100 mM, with K63 chains requiring higher concentrations) and proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) in lysis buffer. Pre-treatment of live cells with MG-132 (5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) can enrich ubiquitinated proteins [42] [29]. |

| Gel Electrophoresis | Poor resolution of ubiquitin chains, leading to a compressed, uninformative smear. | Gel Percentage: Use 8% gels for resolving large chains (>8 ubiquitin units) and 12% gels for better separation of smaller chains (mono- and short chains) [29]. Buffer System: Use MOPS-based buffer to resolve long chains (>8 units) and MES-based buffer for smaller chains (2-5 units) [29]. |

| Protein Transfer | Inefficient transfer of high-MW ubiquitinated proteins or over-transfer of small proteins. | Transfer at a constant 30 V for 2.5 hours to prevent the unfolding of ubiquitin chains, which can mask epitopes. For proteins <25 kDa, use a 0.2 µm PVDF membrane to prevent pass-through [29] [43]. |

| Antibody Detection | Non-specific antibody binding or failure to detect the specific ubiquitin linkages present. | Use PVDF membranes for a stronger signal. Validate antibodies for your application. Be aware that many common anti-ubiquitin antibodies do not recognize all linkage types equally (e.g., poor recognition of M1-linked chains) [29]. For linkage-specific detection, use linkage-specific antibodies or specialized binding tools like TUBEs [4]. |

Advanced Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Enrichment

For a clearer signal, especially for low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins, enrichment before western blotting is often essential. The table below compares modern affinity tools designed for this purpose.

| Research Tool | Function & Mechanism | Key Applications & Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Nanobody) | Uses a high-affinity anti-ubiquitin nanobody (VHH) coupled to beads to immunoprecipitate mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins from cell extracts [42]. | - Fast, clean pulldowns with low background.- Effective for a wide range of organisms (mammalian, yeast, plant).- Useful for IP-MS workflows [42]. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Synthetic peptides containing multiple ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) fused in tandem, resulting in high-affinity binding to polyubiquitin chains [4]. | - Protects ubiquitin chains from DUBs and proteasomal degradation during lysis.- Pan-TUBEs: Bind all chain types.- Linkage-Specific TUBEs: Can differentiate between K48- and K63-linked chains in assays, enabling study of context-dependent ubiquitination [4]. |

| OtUBD Affinity Resin | Uses a high-affinity UBD from Orientia tsutsugamushi coupled to resin to enrich ubiquitinated proteins. Offers both native and denaturing protocols [3]. | - Strongly enriches both mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins.- Denaturing protocols distinguish covalently modified proteins from non-covalent interactors.- A versatile and economical tool for immunoblotting and proteomics [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Linkage-Specific Analysis of Ubiquitination

This protocol uses linkage-specific TUBEs in an ELISA-style format to quantitatively analyze the ubiquitination of an endogenous target protein, such as RIPK2, in response to different stimuli [4].

Workflow Overview

The following diagram illustrates the key steps for using TUBEs to differentiate between K48- and K63-linked ubiquitination of a target protein like RIPK2.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Cell Stimulation and Lysis:

- Treat cells (e.g., THP-1 human monocytic cells) with your stimulus. To induce K63-linked ubiquitination of RIPK2, use 200-500 ng/mL L18-MDP for 30 minutes. To induce K48-linked ubiquitination, use a specific PROTAC (e.g., RIPK2 degrader-2) [4].

- Lyse cells using a buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination. The buffer must contain protease inhibitors, 5-25 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit DUBs, and a proteasome inhibitor like MG-132 [4] [29].

TUBE-Based Capture:

- Coat the wells of a 96-well plate with K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs, and Pan-TUBEs (as a positive control) according to the manufacturer's instructions [4].

- Apply the clarified cell lysates to the respective TUBE-coated wells and incubate to allow binding.

Detection and Analysis:

- After washing, detect the captured ubiquitinated RIPK2 using an anti-RIPK2 primary antibody, followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and a chemiluminescent substrate [4].

- Expected Result: L18-MDP stimulation will produce a strong signal in wells coated with K63-TUBEs and Pan-TUBEs, but not with K48-TUBEs. Conversely, PROTAC treatment will produce a signal with K48-TUBEs and Pan-TUBEs, but not with K63-TUBEs. This clearly differentiates the signaling outcomes [4].

FAQ: Resolving Persistent Problems

My smear is still unresolved and messy after optimization. What else can I do?

If the smear remains uninterpretable, consider these advanced strategies:

- Enrich Your Target: Use immunoprecipitation (IP) with an antibody against your specific protein of interest before performing the ubiquitin western blot. This enriches the target and its modifications, leading to a cleaner background [44].

- Use Ubiquitin Mutants: For in vitro assays, you can determine the specific lysine linkage used in polyubiquitin chains by using a panel of ubiquitin mutants (e.g., "K to R" mutants, which prevent chain formation at a specific lysine, and "K Only" mutants, which allow formation only on a specific lysine) [18].

- Check Antibody Specificity: Run a control where you treat your sample with a deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) prior to loading the gel. A genuine ubiquitin smear should disappear or be significantly reduced [29].

I see no smear at all, only my unmodified protein band. Why?

The absence of a smear can indicate that your target protein is not ubiquitinated under the experimental conditions. However, technical reasons could also be the cause:

- Insufficient Enrichment: The ubiquitinated forms may be below the detection limit. Pre-treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (MG-132) and/or use an enrichment tool like the Ubiquitin-Trap or TUBEs [42] [4].

- Epitope Masking: The epitope recognized by your ubiquitin antibody might be masked in certain chain linkages or configurations. Verify your antibody's specificity and try an antibody raised against a different form of ubiquitin (native vs. denatured) [29] [3].

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually every cellular process, from proteasomal degradation to signal transduction and DNA repair. The ubiquitin code's complexity arises from the diverse architectures of ubiquitin chains, which can vary in length, linkage type (M1, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63), and branching patterns [34]. Among these, K48-linked chains primarily target proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains are involved in signaling pathways and protein trafficking [4]. Recent research has also highlighted the importance of branched ubiquitin chains, such as K11/K48-branched chains, which function as priority degradation signals for the 26S proteasome [5].

Resolving this complex ubiquitin code requires meticulous optimization of electrophoretic conditions. The selection of gel percentage and running buffer significantly impacts the resolution of different ubiquitin chain lengths and types, ultimately determining experimental success or failure. This technical guide provides evidence-based recommendations for optimizing ubiquitin chain resolution, with practical troubleshooting advice for researchers working in ubiquitin biochemistry, drug development, and proteomics.

Technical Specifications: Buffer and Gel Systems for Ubiquitin Chain Resolution

Quantitative Comparison of Electrophoretic Conditions

Table 1: Optimal gel percentages and buffers for resolving ubiquitin chains of different lengths

| Ubiquitin Chain Length | Recommended Gel Percentage | Optimal Running Buffer | Separation Range | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono-ubiquitin & short oligomers (2-5 ubiquitins) | 12% | MES | Low molecular weight (8-40 kDa) | Superior resolution of small ubiquitin oligomers |

| Medium chains (5-15 ubiquitins) | 8% | Tris-glycine | Medium molecular weight | Good separation of individual chains up to 20 ubiquitins |