Optimizing Ubiquitin Enrichment: Advanced Strategies to Minimize Non-Specific Binding for Cleaner Results

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on overcoming the critical challenge of non-specific binding in ubiquitin enrichment workflows.

Optimizing Ubiquitin Enrichment: Advanced Strategies to Minimize Non-Specific Binding for Cleaner Results

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on overcoming the critical challenge of non-specific binding in ubiquitin enrichment workflows. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we detail specific methodologies including Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs), chemical biology tools, and optimized commercial kits that significantly enhance specificity. The content further addresses systematic troubleshooting, protocol optimization for various sample types, and rigorous validation techniques using mass spectrometry and functional assays. By synthesizing current methodologies and emerging technologies, this resource aims to empower scientists with practical strategies for obtaining highly specific ubiquitination data, ultimately accelerating research in proteomics, biomarker discovery, and targeted protein degradation therapeutics.

Understanding the Ubiquitin Enrichment Challenge: Why Non-Specific Binding Occurs

The Critical Impact of Non-Specific Binding on Data Quality and Interpretation

In ubiquitin enrichment research, non-specific binding (NSB) refers to the undesirable adherence of biomolecules (like proteins or contaminants) to your experimental surfaces—such as sensor chips, affinity resins, or antibodies—through interactions that are not related to the specific ubiquitin modification you are trying to study [1]. This phenomenon is a critical technical challenge that can lead to increased background noise, false positive signals in pull-down assays, misinterpretation of mass spectrometry (MS) data, and ultimately, a loss of sensitivity and reliability in detecting genuine ubiquitination events [2] [1]. Effectively controlling for NSB is therefore not merely an optimization step but a fundamental requirement for producing high-quality, interpretable data on the ubiquitin code.

FAQs on Non-Specific Binding in Ubiquitin Research

1. What are the primary causes of non-specific binding in ubiquitin enrichment experiments? NSB in ubiquitin studies arises from several factors:

- Sensor Surface or Resin Chemistry: The nature of the affinity resin (e.g., Ni-NTA, Strep-Tactin, or antibody-coupled beads) can passively interact with non-target proteins. For instance, Ni-NTA agarose can co-purify histidine-rich proteins, and anti-biotin resins can bind endogenously biotinylated proteins when using Strep-tagged ubiquitin systems [2].

- Sample Impurities: Contaminants in your cell or tissue lysates, such as lipids, nucleic acids, or other proteins, can bind to the experimental surfaces or to the capture molecules themselves, generating false-positive signals [1].

- Suboptimal Buffer Conditions: The pH, ionic strength, and composition of your binding and wash buffers can significantly influence electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. Incorrect conditions can promote NSB [1].

2. How can I distinguish between specific ubiquitination signals and non-specific binding?

- Well-Designed Controls: The most robust method is to include control experiments. For immunoblotting or affinity pull-downs, this involves performing the enrichment in the presence of a saturating concentration of an unlabeled competitive ligand (e.g., free ubiquitin) or using a lysate from cells where the E3 ligase of interest is knocked out. The signal remaining in these control conditions is representative of NSB and should be subtracted from your experimental data [3].

- Kinetic Analysis: In real-time binding studies like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), specific interactions typically show characteristic association and dissociation phases. In contrast, NSB often displays rapid, non-saturable association and slower, less structured dissociation [1].

- Mass Spectrometry Follow-up: After enrichment, specific ubiquitinated peptides can be identified by the signature diglycine (Gly-Gly) remnant left on lysine residues after tryptic digestion and MS analysis. The absence of this signature on bound proteins suggests NSB [2] [4].

3. My western blot for ubiquitin shows a high background smear. Is this non-specific binding? Not necessarily. A characteristic smear on a ubiquitin western blot is often indicative of a successful enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins, which have varying molecular weights due to different chain lengths and linkages [5]. However, a high background signal between expected bands or a strong signal in your negative control lanes is a clear sign of NSB. This can be caused by non-specific antibody interactions or insufficient blocking of the membrane.

4. Which ubiquitin enrichment method is least prone to non-specific binding? No single method is immune, but some are designed to minimize it. Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) and high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) like OtUBD offer high specificity for ubiquitin, reducing background [6]. The key is to choose a method appropriate for your question. For example, while tagged ubiquitin systems (e.g., His- or Strep-tag) are easy to use, they are prone to the NSB issues mentioned above. Antibody-based methods work on endogenous proteins but can have lot-to-lot variability and high cost [2] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Background in Affinity Purification and Western Blot

Symptoms: Strong ubiquitin signal in negative control samples (e.g., no primary antibody, sample from ubiquitin-knockdown cells), or a diffuse, high background across the entire lane obscuring specific bands.

Solutions:

- Optimize Blocking: Ensure you are using an effective blocking agent (e.g., 5% BSA or non-fat milk) for a sufficient time (at least 1 hour at room temperature) before antibody incubation.

- Include Control Experiments: Always run a parallel experiment with a control resin (e.g., bare agarose beads) or in the presence of a competing free ubiquitin to define and subtract the NSB signal [3].

- Increase Wash Stringency: Incorporate additional washes with buffers containing mild detergents (e.g., 0.1% Tween-20) or increasing salt concentrations (e.g., 300-500 mM NaCl) to disrupt non-specific electrostatic interactions [6].

- Use Denaturing Conditions: For pull-downs, using strong denaturants like 1-2% SDS in the lysis buffer can help dissociate non-covalent protein interactors from covalently ubiquitinated proteins, providing a cleaner result [6].

Problem: Excessive Non-Specific Binding in SPR Sensorgrams

Symptoms: A rapid, large response unit (RU) signal that does not saturate and exhibits little dissociation, making kinetic analysis of the specific ubiquitin-ligase interaction impossible.

Solutions:

- Surface Optimization: Use a sensor chip with a low propensity for NSB and ensure the ligand (e.g., ubiquitin or a UBD) is properly oriented and immobilized.

- Buffer Additives: Include additives in the running buffer that reduce NSB, such as surfactant P20 (0.05%), carboxymethyl dextran, or chaotropic agents [1].

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge or filter your analyte samples just before injection to remove any aggregates or particulate matter that can non-specifically stick to the sensor chip [1].

- Reference Subtraction: Always use a reference flow cell (with no ligand or an irrelevant ligand immobilized) and subtract its signal from the active flow cell to account for bulk refractive index changes and system-specific NSB [1].

Problem: Co-precipitation of Non-Ubiquitinated Proteins in MS Workflows

Symptoms: Mass spectrometry analysis of your ubiquitin pull-down identifies a large number of proteins lacking the diglycine modification, suggesting they are non-specifically bound contaminants.

Solutions:

- Tandem Enrichment (Double Pull-Down): Use a tandem purification strategy. For example, if using tagged ubiquitin, perform a first enrichment with the tag-specific resin, then elute and subject the eluate to a second round of enrichment with a ubiquitin-specific antibody or UBD (OtUBD) [2].

- Work in Denaturing Conditions: To isolate the covalent "ubiquitinome" from the non-covalent "interactome," lyse cells in buffers containing 1% SDS or 6 M Guanidine-HCl. This denatures proteins and disrupts nearly all non-covalent interactions, ensuring that only covalently modified proteins are purified in subsequent steps [6].

- Use Specific Enzymes: Treat your enriched samples with a broad-spectrum deubiquitinase (DUB) as a control. A genuine ubiquitin signal should be sensitive to DUB treatment, while NSB will remain.

Essential Methodologies for Ubiquitin Enrichment

The table below summarizes the primary methods used to enrich ubiquitinated proteins, along with their associated NSB challenges and advantages.

Table 1: Comparison of Ubiquitin Enrichment Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Common Sources of NSB | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tagged Ubiquitin [2] | Expression of His-, HA-, or Strep-tagged Ub in cells; enrichment via tag-specific resin. | Co-purification of histidine-rich or endogenously biotinylated proteins. | Easy to use, relatively low-cost, high-throughput compatible. |

| Antibody-Based [2] [5] | Use of anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK2) to immunoprecipitate endogenous ubiquitinated proteins. | Non-specific antibody cross-reactivity and binding to protein A/G beads. | Works on endogenous proteins without genetic manipulation; linkage-specific antibodies available. |

| UBD-Based (e.g., TUBEs, OtUBD) [2] [6] | Use of single or tandem ubiquitin-binding domains to capture ubiquitin conjugates. | Lower affinity single UBDs can have poor recovery; can bind free ubiquitin. | High affinity and specificity; can protect chains from DUBs; works under denaturing conditions (OtUBD). |

| Kits (e.g., Pierce) [7] | Proprietary affinity resin supplied with optimized buffers for enrichment. | Varies by kit chemistry, but similar to general resin-based NSB issues. | Fast, convenient, and complete; includes necessary reagents and protocols. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Enrichment

| Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG-132, Epoxomicin) [5] | Blocks degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, leading to their accumulation and increased detection signal. | Treat cells with 5-25 µM MG-132 for 1-2 hours before harvesting to boost ubiquitin levels. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors (e.g., N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM), PR-619) [6] | Prevents the cleavage of ubiquitin chains by endogenous DUBs during lysate preparation, preserving the ubiquitination signal. | Add 10-25 mM NEM to cell lysis buffer to inactivate DUBs. |

| High-Affinity UBD Resins (e.g., OtUBD, TUBEs) [6] | Provides a highly specific matrix for pulling down mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins with low background. | Use OtUBD resin with harsh wash buffers (e.g., containing 1 M NaCl) to minimize NSB while retaining target proteins. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies [2] [4] | Allows for the specific detection or enrichment of ubiquitin chains with a particular linkage (e.g., K48, K63). | Use a K48-linkage specific antibody to confirm if a protein is targeted for proteasomal degradation. |

| Diglycine (Gly-Gly) Remnant Antibodies [8] | Enables the proteomic-level identification of ubiquitination sites by specifically enriching for tryptic peptides containing the Gly-Gly lysine modification. | Use after tryptic digestion of enriched samples for LC-MS/MS analysis to map ubiquitination sites. |

Experimental Workflow and NSB Control Points

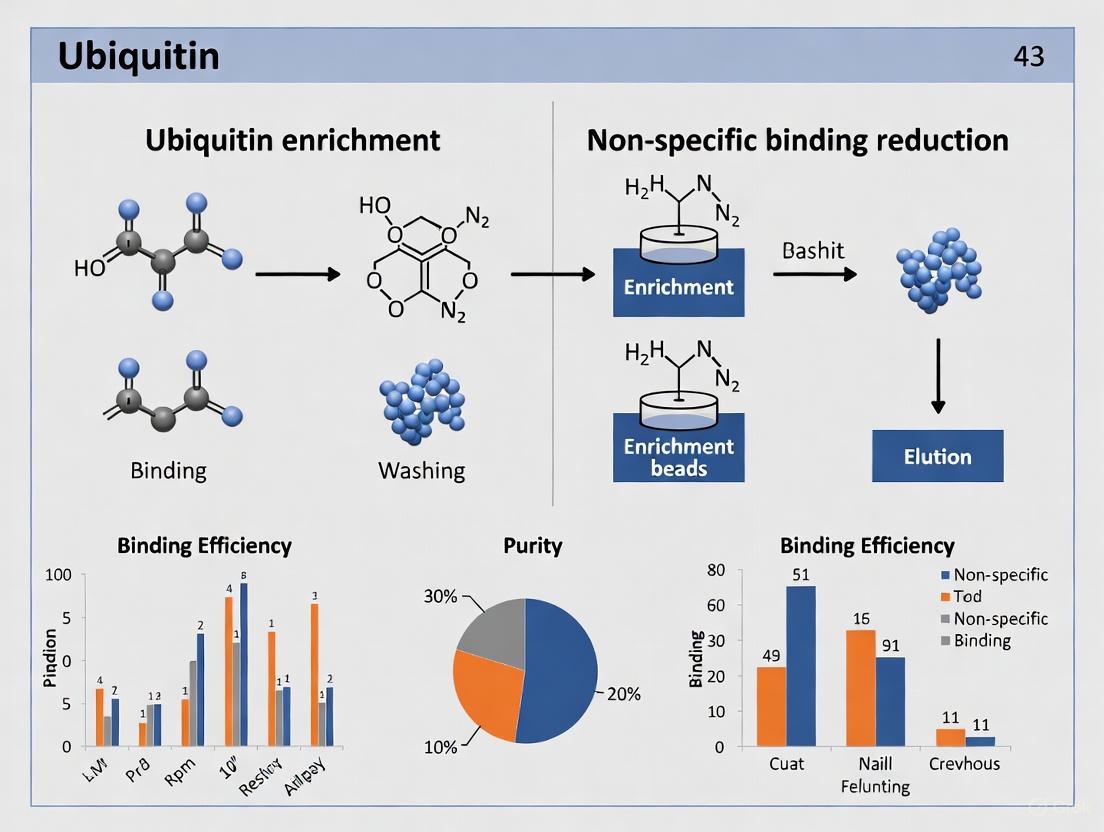

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for ubiquitin enrichment, highlighting key steps where NSB can occur and the corresponding mitigation strategies.

Fundamental Principles of Ubiquitin-Binding Interactions and Affinity Matrices

Ubiquitination is a versatile post-translational modification involving the covalent attachment of ubiquitin (Ub), a 76-amino acid protein, to target substrates. This process regulates diverse cellular functions including protein degradation, signal transduction, DNA repair, and endocytosis. The specificity of ubiquitin signaling is governed by the topology of ubiquitin chains, which can vary in length and linkage type. Eight distinct linkage types exist (M1, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63), each potentially encoding different functional outcomes. Understanding the fundamental principles of ubiquitin-binding interactions and affinity matrices is essential for reducing non-specific binding in ubiquitin enrichment research, enabling more accurate characterization of ubiquitin-mediated processes in health and disease.

FAQs: Ubiquitin-Binding and Enrichment Challenges

1. What are the primary causes of non-specific binding in ubiquitin pull-down assays?

Non-specific binding in ubiquitin enrichment experiments commonly results from antibody cross-reactivity, insufficient blocking, inadequate washing stringency, or protein degradation. Polyclonal antibodies, while useful for detecting multiple epitopes, are particularly prone to promiscuous binding. Additionally, the weak affinities of individual ubiquitin-binding domains (typically in the μM range) can lead to non-specific interactions if not properly optimized in experimental conditions. Using high antibody concentrations can exacerbate this problem, as can the presence of protein multimers or degraded protein fragments that share epitopes with your target.

2. Why might my ubiquitin western blot show unexpected bands or smears?

Ubiquitinated proteins often appear as smears or multiple bands on western blots due to several factors: the natural heterogeneity of ubiquitin chain length and linkage type; the formation of protein multimers; partial protein degradation; or the presence of different ubiquitinated protein species. This pattern is actually characteristic of ubiquitinated samples, as the Ubiquitin-Trap captures monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin polymers, and ubiquitinylated proteins of varying lengths. However, discrete non-specific bands may indicate antibody cross-reactivity, insufficient protease inhibition during sample preparation, or protein subtypes/splice variants with similar epitopes.

3. How can I improve the specificity of ubiquitin linkage detection?

To enhance linkage-specific detection, employ multiple complementary approaches: (1) Use linkage-specific reagents such as Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) with nanomolar affinities for particular chain types; (2) Incorporate proteolytically stable ubiquitin variants in pull-down assays using chemical biology approaches like genetic code expansion or click chemistry; (3) Validate findings with multiple detection methods including linkage-specific antibodies when available; (4) Include appropriate controls such as ubiquitin mutants (e.g., lysine-to-arginine mutations) to verify specificity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Background and Non-Specific Binding in Ubiquitin Enrichment

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Inefficient blocking

- Solution: Increase blocking reagent concentration (e.g., from 2% to 5% BSA), extend blocking incubation times, and prepare primary antibody in blocking buffer. Add Tween-20 (0.05%) to blocking buffer if not already present.

Cause: Inadequate washing

- Solution: Ensure sufficient washing buffer volume to cover the blot, wash with gentle agitation, increase washes to 4-5 times for 5 minutes each, and consider increasing Tween-20 concentration to 0.1%.

Cause: Antibody-related issues

- Solution: For polyclonal antibodies showing promiscuous binding, switch to monoclonal antibodies when possible. Titrate antibody to determine optimal concentration that minimizes non-specific binding. Always use fresh aliquots of antibodies to maintain specificity.

Cause: Protein degradation

- Solution: Add protease inhibitors to lysis buffer and maintain samples at 4°C during preparation. Precipitate proteins with acetone or TCA to immediately denature and inactivate proteases. Avoid overexposure to urea which can lead to protein degradation.

Problem: Inconsistent Ubiquitin Enrichment Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Variable ubiquitination levels

- Solution: Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors like MG-132 (5-25 μM for 1-2 hours) prior to harvesting to preserve ubiquitination signals. Optimize concentration and duration for each cell type to avoid cytotoxicity.

Cause: Insufficient binding capacity

- Solution: Note that precise binding capacity for ubiquitin chains is difficult to determine as chains can bind at single or multiple sites. Use fresh resin and avoid overloading the affinity matrix. For Ubiquitin-Trap products, follow manufacturer recommendations for sample-to-resin ratios.

Cause: Interference from endogenous proteins

- Solution: When using His-tag systems, be aware that histidine-rich proteins may co-purify. For Strep-tag systems, endogenously biotinylated proteins may cause interference. Include appropriate controls to identify these contaminants.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Enrichment and Detection

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Matrices | Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose/Magnetic Agarose (ChromoTek) | Immunoprecipitation of monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin polymers, and ubiquitinylated proteins from various cell extracts using anti-ubiquitin nanobody. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, Pan-TUBE (LifeSensors) | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitin chains with linkage specificity (K48, K63) or pan-specificity for general ubiquitin enrichment. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific, M1-linkage specific | Detection and enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins with specific chain linkages via western blot or immunoprecipitation. |

| Chemical Biology Tools | Genetic Code Expansion (GCE), Click Chemistry (CuAAC), Thiol Chemistry | Generation of defined, proteolytically stable ubiquitin variants for structural and interactome studies. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG-132 | Preserves ubiquitination signals by inhibiting proteasomal degradation of ubiquitinated proteins. |

| Tagged Ubiquitin Systems | His-tagged Ub, Strep-tagged Ub, HA-tagged Ub | Expression systems for purifying ubiquitinated substrates from cellular environments. |

Quantitative Data on Ubiquitin-Binding Affinities

Table: Binding Affinities of Ubiquitin-Binding Domains to Mono-Ubiquitin

| Ub-Binding Domain | Source Protein | Kd (μM) | Method | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBA | Dsk2 | 14.8 ± 5.3 | SPR | Three-helical bundle binding Ile44 hydrophobic patch |

| UBA | hHR23A | 400 ± 100 | NMR | Three-helical bundle (UBA2) |

| CUE | Vps9 | 20 ± 1 | ITC | Structurally homologous to UBA domains |

| UIM | Vps27 (UIM1) | 277 ± 8 | NMR | Single α-helix binding shallow hydrophobic groove on ubiquitin |

| UIM | S5a (UIM2) | 73 | NMR | Single α-helix with conserved alanine residue |

| MIU | Rabex-5 | 29 ± 4.8 | SPR/ITC | Helical domain interacting with Ile44 patch |

| ZnF UBP | Isopeptidase T | 2.8 | ITC | Zinc finger domain with high affinity for ubiquitin |

| GAT | TOM1 | 409 ± 13 | SPR | helical domain with distinct binding mode for Ile44 patch |

Experimental Workflows for Specific Ubiquitin Enrichment

Methodology 1: TUBE-Based Enrichment for Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination

Principle: Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) consist of multiple ubiquitin-binding domains fused together, creating high-affinity reagents with specificity for particular ubiquitin chain linkages. These can discriminate between different biological functions, such as K63-linked chains in inflammatory signaling versus K48-linked chains in proteasomal degradation.

Protocol:

- Cellular Treatment and Lysis: Culture THP-1 cells and treat with either L18-MDP (200-500 ng/mL for 30-60 min) to induce K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2 or with PROTAC degrader to induce K48 ubiquitination. Lyse cells using buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination (e.g., containing protease inhibitors and N-ethylmaleimide to inhibit deubiquitinases).

- TUBE Coating: Coat 96-well plates with chain-specific TUBEs (K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, or Pan-TUBE) according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Sample Incubation: Incubate cell lysates (50-100 μg total protein) in TUBE-coated plates for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Washing: Wash plates extensively with wash buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20 to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Target Detection: Detect specifically bound ubiquitinated proteins by immunoblotting with target-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-RIPK2).

- Validation: Include controls such as ubiquitin mutants (K48R or K63R) or specific pathway inhibitors (e.g., Ponatinib for RIPK2) to verify linkage specificity.

Methodology 2: Chemical Biology Approaches for Defined Ubiquitin Variants

Principle: Chemical biology tools enable generation of defined ubiquitin variants with proteolytically stable linkages, which can be used as affinity matrices to identify interacting proteins through mass spectrometry. These approaches overcome the limitations of enzymatic generation of ubiquitin chains and the lability of native isopeptide bonds.

Protocol for Click Chemistry-Generated Diubiquitin:

- Ubiquitin Functionalization: Synthesize ubiquitin monomers functionalized with either azide (using azido-ornithine incorporation at desired positions via SPPS) or alkyne groups (using propargylamine coupled to C-terminus).

- Click Reaction: Perform copper(I)-catalyzed alkyne-azide cycloaddition (CuAAC) using CuSO4 and sodium ascorbate to generate diubiquitin linked via triazole bonds. These mimic native isopeptide bonds while being resistant to hydrolysis by deubiquitinases.

- Affinity Matrix Preparation: Immobilize triazole-linked ubiquitin chains on appropriate resin (e.g., agarose beads) following standard coupling procedures.

- Affinity Enrichment: Incubate affinity matrix with cell lysates under near-physiological conditions (2-4 hours at 4°C) to allow binding of ubiquitin-interacting proteins.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads extensively with buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20, then elute bound proteins with SDS-PAGE sample buffer or low pH elution buffer.

- MS Identification: Separate eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE, perform in-gel tryptic digestion, and identify interacting proteins by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with label-free quantification.

Ubiquitin Signaling Pathways and Technical Challenges

Ubiquitin Linkage Diversity and Functional Consequences:

The ubiquitin code encompasses tremendous complexity, with different linkage types directing distinct functional outcomes. K48-linked chains primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains regulate non-proteolytic functions including inflammatory signaling and protein trafficking. Less common linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, M1) play roles in specific processes such as DNA repair, autophagy, and immune signaling. This diversity presents both challenges and opportunities for research and therapeutic development.

Technical Considerations for Reducing Non-Specific Binding:

- Ubiquitin-Binding Domain Affinities: Individual ubiquitin-binding domains typically exhibit weak affinities (Kd > 100 μM), which cells leverage through avidity effects using multiple domains or oligomerization. Researchers can mimic this strategy by using tandem domains (e.g., TUBEs) rather than single domains for enrichment.

- Epitope Exposure: The Ile44 hydrophobic patch on ubiquitin serves as the primary interaction surface for many UBDs. Maintaining the structural integrity of this region during experimental procedures is essential for specific binding interactions.

- Stability Considerations: The native isopeptide bond between ubiquitin and substrates is highly labile due to cellular deubiquitinases. Using DUB inhibitors during sample preparation and proteolytically stable ubiquitin analogs (e.g., triazole linkages) in pull-down assays can significantly reduce false negatives.

- Specificity Validation: Always include critical controls such as competition with free ubiquitin, ubiquitin mutants, and pathway-specific inhibitors to confirm the specificity of observed interactions.

Protein ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification regulating diverse cellular functions, but its proteomic analysis faces significant challenges due to low stoichiometry and the transient nature of the modification. A primary technical hurdle in ubiquitin proteomics is non-specific binding during enrichment procedures, which can compromise data quality, reduce sensitivity for genuine ubiquitination events, and lead to false positives. Non-specific binding refers to the unintended co-purification of proteins or peptides that are not the target of interest. This guide addresses the common sources of this interference and provides proven methodologies to mitigate it, enabling cleaner and more reliable results in ubiquitination research.

FAQ 1: Why is my ubiquitin western blot a smear with high background, and how can I resolve this?

Issue: A smeared appearance with high background is a classic symptom of non-specific binding during the immunoprecipitation (IP) step. This often occurs because the affinity beads capture abundant, non-ubiquitinated proteins alongside the target ubiquitinated species.

Primary Sources:

- Abundant Protein Contamination: Ubiquitin affinity reagents can non-specifically interact with highly abundant cellular proteins.

- Endogenous Biotinylated Proteins: When using Strep-tag based Ub purification systems, endogenously biotinylated proteins can bind to the Strep-Tactin resin [2].

- His-Rich Proteins: When using His-tagged ubiquitin and Ni-NTA purification, proteins rich in histidine residues can co-purify [2].

- Incomplete Blocking: The affinity beads or the IP system may have insufficient blocking, leading to nonspecific protein adherence.

Solutions:

- Optimize Wash Stringency: Increase the salt concentration or add mild detergents (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100) to the wash buffer. Consistently use a wash buffer like BlastR Wash Buffer for multiple rigorous washes [9].

- Include Specific Controls: Always run a parallel IP with control beads (e.g., beads without the ubiquitin-binding entity) to identify proteins that bind non-specifically to the bead matrix itself. Subtract these identifications from your experimental sample [9].

- Use Denaturing Conditions: Perform lysis and IP under denaturing conditions (e.g., using 1% SDS in the lysis buffer) to disrupt non-covalent protein-protein interactions that cause co-purification. This must be compatible with your enrichment reagent [9].

- Pre-clear Lysate: Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., 10,000-16,000 g) to remove insoluble debris. Some protocols also incubate the lysate with control beads before the actual IP to pre-clear non-specific binders.

FAQ 2: I am using tagged ubiquitin for pull-downs. What are the specific non-binding risks with this approach?

Issue: While expressing tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, Strep, or HA) is a common enrichment strategy, it introduces several specific artifacts that lead to non-specific binding and misinterpretation of data.

Primary Sources:

- Competition with Endogenous Ubiquitin: The expressed tagged ubiquitin may not fully recapitulate the endogenous ubiquitin dynamics, and the presence of both tagged and untagged ubiquitin pools can lead to incomplete enrichment and complex artifacts [2] [10].

- Tag-Specific Interactions: As noted, His-tags bind histidine-rich proteins, and Strep-tags bind endogenous biotinylated proteins [2].

- Structural Alterations: The tag itself may alter the structure of ubiquitin or its ability to form certain chain types, potentially creating unnatural ubiquitination events or failing to mimic endogenous modification patterns [2].

Solutions:

- Choose the Tag Carefully: For mammalian cells, the Stable Tagged Ubiquitin Exchange (StUbEx) system can help replace the endogenous pool with tagged ubiquitin, reducing competition artifacts [2].

- Validate Findings: Corroborate key findings from tagged-ubiquitin experiments with an orthogonal method, such as using pan-specific or linkage-specific Ub antibodies on endogenous proteins.

- Use Tandem Enrichment: To move beyond tag-based limitations, consider methods like the SCASP-PTM protocol, which allows for the enrichment of endogenously ubiquitinated peptides from complex lysates without genetic manipulation, thereby avoiding tag-related artifacts [11].

FAQ 3: How does antibody quality contribute to non-specific binding, and how can I select the best reagent?

Issue: Antibodies are powerful tools for enriching endogenously ubiquitinated proteins, but their quality is paramount. Low-affinity or non-specific antibodies are a major source of false positives and high background.

Primary Sources:

- Cross-Reactivity: Antibodies may recognize epitopes on non-ubiquitin proteins that share similarity with the immunogen.

- Low Affinity: Low-affinity antibodies require a higher amount of antibody and lysate, increasing the chance of non-specific interactions.

- Impure Antisera: Polyclonal antisera can contain antibodies against various contaminants from the immunogen preparation.

Solutions:

- Use High-Affinity Binders: Employ engineered high-affinity reagents like Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) or Ubiquitin-Trap nanobodies. TUBEs, with their avidity effect, show nanomolar affinity for polyubiquitin chains and can outcompete low-affinity non-specific interactions [12] [13]. The Ubiquitin-Trap is noted for producing clean, low-background IPs due to its high specificity [13].

- Select Linkage-Specific Reagents: For studying specific chain types, use well-validated linkage-specific TUBEs or antibodies. These reagents are precisely characterized to enrich for a particular linkage (e.g., K48 or K63), dramatically reducing background from other chain types [12].

- Verify Antibody Specificity: Always validate the specificity of an antibody using controls such as ubiquitin-deficient cell lines, linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs), or competing with free ubiquitin.

FAQ 4: What sample preparation factors can increase non-specific binding?

Issue: The initial steps of sample preparation are critical. Suboptimal handling of cell lysates can greatly exacerbate problems with non-specific binding downstream.

Primary Sources:

- Incomplete Lysis and Viscosity: Crude lysates can be viscous due to released DNA, which can trap proteins non-specifically and clog columns or hinder bead binding [9].

- Protease and Deubiquitinase Activity: During lysis, active proteases can degrade proteins, while deubiquitinases (DUBs) can remove ubiquitin from substrates, both of which distort the true ubiquitination landscape and can generate fragments that bind non-specifically.

Solutions:

- Employ Robust Lysis Protocols: Use lysis buffers containing benzonase or other nucleases to digest DNA and reduce viscosity. Filter lysates using specialized filters (e.g., BlastR Filters) to remove particulate matter [9].

- Use Protease and DUB Inhibitors: It is essential to add broad-spectrum protease inhibitors and, crucially, DUB inhibitors (e.g., PR-619, N-Ethylmaleimide) to the lysis buffer immediately upon cell disruption. This preserves the native ubiquitination state of proteins [9].

- Stabilize Ubiquitination: Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) for a few hours before harvesting. This prevents the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins and increases their abundance for detection, reducing the need for excessive starting material that can increase background [13].

Table 1: Common Sources of Non-Specific Binding and Their Impact

| Source Category | Specific Example | Consequence | Frequency in Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tag-Based Enrichment | Co-purification of histidine-rich proteins with His-tag systems [2] | Masks low-abundance ubiquitinated targets | High |

| Co-purification of endogenous biotinylated proteins with Strep-tag systems [2] | False positives in mass spectrometry | High | |

| Antibody-Based Enrichment | Low-affinity or cross-reactive pan-ubiquitin antibodies [2] | High background, smeared western blots | Very High |

| Sample Preparation | Incomplete lysis and viscous DNA in lysate [9] | Trapping of non-target proteins, clogged columns | Common |

| Inadequate DUB inhibition [9] | Loss of signal, altered ubiquitination profile | Very Common | |

| Cellular Context | Abundant non-target proteins | Saturation of binding capacity, reduced sensitivity | Ubiquitous |

Table 2: Comparison of Ubiquitin Enrichment Reagents and Non-Specific Binding Potential

| Enrichment Reagent | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages / Non-Specific Binding Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| His-Tag / Ni-NTA [2] | Affinity purification of His-tagged Ub | Relatively low cost, easy to use | High risk from His-rich proteins; requires genetic manipulation |

| Strep-Tag / Strep-Tactin [2] | Affinity purification of Strep-tagged Ub | High specificity and affinity | Risk from endogenous biotinylated proteins; requires genetic manipulation |

| Pan-Ubiquitin Antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK2) [2] | Immunoaffinity for ubiquitin | Works on endogenous proteins | High risk of cross-reactivity and low-affinity binding; high cost |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) [12] | High-affinity UBDs in tandem | Nanomolar affinity, protects chains from DUBs, low background | May have linkage preferences; requires characterization |

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Nanobody) [13] | High-affinity VHH binding to Ub | Clean IPs, stable under harsh washes, low background | Not linkage-specific; will bind all ubiquitin conjugates |

| diGly Antibody (K-ε-GG) [10] | Enriches tryptic peptides with GlyGly remnant | Direct site identification, works on any sample | Cannot provide protein-level or chain linkage information |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Clean Immunoprecipitation of Ubiquitinated Proteins Using Magnetic Beads

This protocol is adapted from commercial best practices and is designed to minimize non-specific binding through stringent washes and appropriate controls [9].

Materials:

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., BlastR Lysis Buffer with 1% SDS)

- Dilution Buffer (e.g., BlastR Dilution Buffer)

- Protease and Deubiquitinase Inhibitor Cocktails

- Wash Buffer (e.g., BlastR Wash Buffer)

- High-affinity ubiquitin binding beads (e.g., TUBE-magnetic beads or Ubiquitin-Trap Magnetic Agarose)

- Control beads (beads without ubiquitin-binding ligand)

- Cell scraper, BlastR filters, magnetic rack, rotating platform.

Method:

- Inhibitor-Enhanced Lysis: Grow and treat cells as required. Wash cells with PBS. Lyse cells in Lysis Buffer supplemented with protease and DUB inhibitors. Use a cell scraper for efficient lysis. The initial use of an SDS-containing buffer helps denature proteins and disrupt non-covalent interactions.

- Clarification and Dilution: Pass the viscous lysate through a BlastR filter using a plunger to remove DNA and debris. Collect the flow-through. Critically, dilute the lysate 1:5 with Dilution Buffer to reduce the SDS concentration to a level compatible with the affinity beads, while maintaining a denaturing environment.

- Quantification and Pre-clearing (Optional): Quantify protein concentration. A starting point of 1.0 mg of total protein per IP is recommended. To reduce non-specific binding, the lysate can be pre-cleared by incubating with control beads for 30 minutes.

- Binding with Controls: Aliquot washed affinity beads and control beads into separate tubes. Add the diluted lysate to both the IP tube and the Control IP tube. Incubate on a rotating platform at 4°C for 2 hours.

- Stringent Washes: Collect beads using a magnetic rack. Aspirate the supernatant. Wash the beads three times with 1 mL of Wash Buffer, incubating for 5 minutes on a rotator with each wash. This step is crucial for removing loosely bound, non-specific proteins.

- Elution: After the final wash, completely remove the supernatant. Add 30 µL of Bead Elution Buffer (a low-ppH buffer or SDS sample buffer) to the beads, resuspend by flicking, and incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes. Transfer the suspension to a spin column and centrifuge to collect the clean eluate.

- Analysis: Add reducing agent (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol) and boil the samples for 5 minutes. Analyze by SDS-PAGE and western blotting.

Protocol 2: Tandem Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Peptides for Mass Spectrometry (SCASP-PTM)

This modern protocol allows for the sequential enrichment of multiple PTMs, including ubiquitination, from a single sample, improving specificity and throughput [11].

Materials:

- SDS-cyclodextrin-assisted sample preparation (SCASP) reagents

- diGly remnant (K-ε-GG) antibody-conjugated beads

- Trypsin

- C18 desalting tips or columns

- Mass spectrometry-compatible buffers.

Method:

- Protein Extraction and Digestion: Extract proteins using the SCASP method, which utilizes SDS and cyclodextrin to efficiently solubilize proteins while maintaining compatibility with downstream enzymatic steps. Digest the extracted proteins with trypsin.

- Primary Enrichment (Ubiquitinated Peptides): Without an intermediate desalting step (which can cause peptide loss), subject the protein digest to enrichment using anti-diGly antibody beads. This directly captures peptides containing the GlyGly remnant left after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins.

- Secondary Enrichment from Flow-Through: Collect the flow-through from the first enrichment. This flow-through, now largely devoid of ubiquitinated peptides, can be subsequently used for the serial enrichment of other PTMs, such as phosphorylation or glycosylation, without the need for desalting.

- Cleanup and MS Analysis: Desalt the enriched ubiquitinated peptides using C18 tips. The peptides are then analyzed by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Data-independent acquisition (DIA) methods are recommended for comprehensive and quantitative profiling.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow that integrates solutions for minimizing non-specific binding, from sample preparation to analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Clean Ubiquitin Enrichment

| Reagent | Function | Key Feature for Reducing NSB | Example Product/Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUB Inhibitors | Prevents deubiquitination during lysis, preserving signal | Stabilizes the target, reducing degradation-related artifacts | PR-619, N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) [9] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Increases abundance of polyubiquitinated proteins | Allows use of less lysate, reducing co-purified background | MG-132 [13] |

| High-Affinity TUBEs | Enriches polyubiquitin chains with high avidity | Nanomolar affinity outcompetes low-affinity non-specific interactions; protects from DUBs [12] | K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, Pan-TUBE [12] |

| Ubiquitin-Trap | Nanobody-based IP of ubiquitin conjugates | Engineered for high specificity and stability under harsh wash conditions [13] | ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose/Magnetic [13] |

| diGly Remnant Antibody | Enriches ubiquitinated peptides for MS | Directly targets the covalent modification, highly specific for site identification [10] | Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody |

| Control Beads | Identifies non-specific binders to bead matrix | Essential control for subtracting background in MS and WB | Beads without ubiquitin ligand [9] |

High-Specificity Enrichment Tools: From TUBEs to Chemical Biology

The study of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is fundamental to understanding cellular homeostasis, signaling, and the mechanisms of targeted protein degradation. A significant technical challenge in this field is the specific enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins from complex cellular lysates. Non-specific binding during pull-down assays can lead to high background noise, masking genuine ubiquitination signals and producing unreliable data. The development of Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) addresses this issue by providing reagents engineered for high-affinity and linkage-specific binding to polyubiquitin chains, thereby reducing non-specific interactions and protecting ubiquitin modifications from deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) during processing [12] [14].

TUBEs are recombinant proteins typically composed of multiple ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains arranged in tandem. This design confers a nanomolar affinity for polyubiquitin chains, which is significantly stronger than that of single UBA domains. Their high affinity allows TUBEs to effectively compete with cellular DUBs, preserving the labile ubiquitin signal in experiments [12] [14]. A key advancement is the development of chain-selective TUBEs, which are engineered to preferentially recognize specific ubiquitin linkage types, such as the degradation-associated K48-linked chains or the signaling-associated K63-linked chains [12]. This specificity enables researchers to dissect the complex biological functions of different ubiquitin codes.

Table 1: Common Ubiquitin Linkages and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Known Function(s) |

|---|---|

| K48 | Targets proteins for proteasomal degradation [12] [15] |

| K63 | Regulates signal transduction, protein trafficking, and immune responses [12] [15] |

| K6 | Involved in antiviral responses, autophagy, and DNA repair [15] |

| K11 | Associated with cell cycle progression and proteasome-mediated degradation [15] |

| M1 | Regulates cell death and immune signaling [15] |

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of affinity reagents is quantifiable by their sensitivity and dynamic range. The following table summarizes key metrics for TUBEs and a next-generation technology, Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domains (ThUBDs), which were developed to address some limitations of first-generation TUBEs.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Ubiquitin-Binding Reagents

| Technology | Affinity/Sensitivity | Key Feature | Linkage Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional TUBEs | Nanomolar affinity (K_d) [12] | High-affinity capture, protection from DUBs | Available as pan-selective or chain-selective (e.g., K48, K63) [12] |

| ThUBD-coated plates | 16-fold wider linear range and higher sensitivity than TUBE-coated plates [16] | Unbiased recognition of all ubiquitin chain types | Designed for unbiased capture, though specific applications may vary [16] |

Experimental Protocol: Using Chain-Specific TUBEs in a 96-Well Plate Format

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating the linkage-specific ubiquitination of RIPK2, demonstrating the high-throughput application of TUBE technology [12].

Materials:

- Chain-specific TUBE-coated plates: e.g., K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, or Pan-TUBE coated 96-well plates.

- Cell lysate: Prepared from treated cells using a lysis buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination (e.g., containing DUB inhibitors).

- Primary antibody: Specific to your protein of interest (e.g., anti-RIPK2).

- HRP-conjugated secondary antibody: Compatible with your primary antibody host species.

- Wash buffer: Typically a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution with a mild detergent.

- ELISA detection reagents: Chemiluminescent or colorimetric substrate compatible with HRP.

- Microplate reader.

Methodology:

Cell Treatment and Lysis:

- Treat cells according to your experimental design. For example, to induce K63-ubiquitination of RIPK2, treat THP-1 cells with 200-500 ng/mL L18-MDP for 30 minutes. To induce K48-ubiquitination, use a specific PROTAC like RIPK2 degrader-2 [12].

- Lyse cells in an appropriate buffer, clarify the lysate by centrifugation, and determine the protein concentration.

Ubiquitin Capture:

- Apply a standardized amount of cell lysate (e.g., 50 µg) to the wells of the chain-specific TUBE-coated plate.

- Incubate for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation to allow ubiquitinated proteins to bind to the TUBEs.

Washing:

- Wash the wells thoroughly with wash buffer multiple times to remove all non-specifically bound proteins.

Target Protein Detection:

- Add a primary antibody against your target protein (e.g., RIPK2) and incubate.

- Wash again to remove unbound primary antibody.

- Add an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and incubate.

- Perform a final wash.

Signal Detection and Quantification:

- Add the HRP substrate to the wells and measure the resulting signal (chemiluminescence or absorbance) using a microplate reader.

- Quantify the level of captured ubiquitinated target protein by comparing to standards or controls.

Workflow Visualization:

High-Throughput TUBE Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for TUBE-based Ubiquitin Enrichment

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chain-Selective TUBEs | Recombinant proteins to immunoprecipitate specific ubiquitin linkages (K48, K63, etc.) [12]. | Differentiating degradative (K48) from non-degradative (K63) ubiquitination of a target protein like RIPK2 [12]. |

| Pan-Selective TUBEs | Recombinant proteins that bind all ubiquitin chain linkages with high affinity [12] [14]. | Capturing the total pool of ubiquitinated proteins from a cell lysate for global ubiquitome analysis. |

| TUBE-coated 96-well Plates | Microplates pre-coated with TUBEs for high-throughput, plate-based ubiquitination assays [12] [16]. | Rapid screening of PROTAC-induced target ubiquitination in a quantitative format [12]. |

| DUB Inhibitors | Small molecules (e.g., MG-132) added to cell culture media and lysis buffers. | Preserving the ubiquitin signal by preventing its removal by deubiquitinating enzymes during sample preparation [15]. |

| Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose/Magnetic Beads | An alternative nanobody-based technology for pulldown of mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins [15]. | Immunoprecipitation of ubiquitinated proteins for downstream analysis by western blot or mass spectrometry. |

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

FAQ 1: My ubiquitin western blot shows a high background smear. How can I reduce this non-specific signal?

- Solution: This is a common challenge. Ensure you are using a high-affinity capture reagent like TUBEs to enrich for true ubiquitination signals over background. Optimize your wash conditions by increasing salt concentration (e.g., 300-500 mM NaCl) or adding a mild detergent to the wash buffer. Always include a control with a TUBE reagent but no cell lysate to identify signal from the reagent itself. Furthermore, treating cells with a proteasome inhibitor like MG-132 (e.g., 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) prior to harvesting can help preserve and enrich for ubiquitinated proteins [15].

FAQ 2: Can TUBEs differentiate between K48 and K63-linked ubiquitination on my protein of interest?

- Solution: Yes, this is a primary application for chain-selective TUBEs. In a study on RIPK2, K63-TUBEs specifically captured the protein after inflammatory stimulation (L18-MDP), while K48-TUBEs captured it upon treatment with a PROTAC degrader. Pan-TUBEs captured the protein in both contexts. To perform this analysis, you would run parallel experiments using different chain-specific TUBEs and compare the enrichment of your target [12].

FAQ 3: I am working with a low-abundance target protein. How can I improve the sensitivity of ubiquitination detection?

- Solution: Consider moving to a more sensitive platform. While TUBE-coated plates offer good sensitivity, newer technologies like Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain (ThUBD)-coated plates have been reported to exhibit a 16-fold wider dynamic range and significantly higher sensitivity for capturing polyubiquitinated proteins from complex proteomes compared to TUBE technology [16]. Maximizing the amount of input protein and using high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrates can also help.

FAQ 4: Why is my ubiquitinated protein yield low after a TUBE pulldown?

- Solution: The transient nature of ubiquitination is a key factor. To protect ubiquitin chains from DUBs, it is critical to include a broad-spectrum DUB inhibitor cocktail in your lysis buffer and perform all steps at 4°C. Also, verify that your lysis buffer is non-denaturing to maintain the native structure of ubiquitin chains required for TUBE recognition. Finally, ensure you are using an adequate amount of TUBE reagent for the amount of lysate input.

FAQ 5: Are there any specific considerations for using TUBEs in mass spectrometry (IP-MS) workflows?

- Solution: TUBEs are compatible with IP-MS. The primary advantage is their ability to protect ubiquitin chains from DUBs, leading to a more representative profile of the ubiquitome. For MS compatibility, ensure you use harsh wash conditions (e.g., high salt) to minimize non-specific co-purifying proteins that can complicate the analysis. Specific protocols for on-bead digestion have been optimized for technologies like the Ubiquitin-Trap, which can serve as a useful guide [15].

Linkage-Specific Antibodies for Selective Ubiquitin Chain Enrichment

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular functions, including protein degradation, signal transduction, and DNA repair. The specificity of ubiquitin signaling is largely determined by the type of polyubiquitin chain formed, with eight distinct linkage types (M1, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) mediating different functional outcomes. Linkage-specific antibodies have become indispensable tools for selectively enriching and detecting these various ubiquitin chain types, enabling researchers to decipher the complex ubiquitin code. However, a significant challenge in these applications is minimizing non-specific binding, which can compromise data quality and lead to erroneous conclusions. This technical resource center addresses common experimental issues and provides optimized protocols to enhance the specificity and reliability of your ubiquitin enrichment studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Ubiquitin Research

The following table summarizes essential reagents used in linkage-specific ubiquitin research:

| Reagent Type | Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-specific, K63-specific, K11-specific [2] [17] | Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence to detect specific ubiquitin linkages. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Pan-TUBEs, K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, M1-TUBE [18] [19] | High-affinity enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates; protect chains from deubiquitinases. |

| Affimers | K6-specific, K33/K11-specific [20] | Non-antibody binding proteins used for linkage-specific detection in blotting, microscopy, and pull-downs. |

| Ubiquitin-Traps | Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose, Ubiquitin-Trap Magnetic Agarose [21] | Immunoprecipitation of monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitinylated proteins from various cell extracts. |

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin | His-Ub, HA-Ub, Strep-Ub [2] | High-throughput purification of ubiquitinated substrates from cultured cells. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: High Background and Non-Specific Binding in Enrichment

- Potential Cause: Non-specific interaction between the affinity resin or antibody and non-ubiquitinated proteins in the lysate.

- Solution:

- Optimize Wash Stringency: Increase the salt concentration (e.g., 300-500 mM NaCl) or add mild detergents (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100) to the wash buffers.

- Use Competitor Proteins: Include inert proteins like bovine serum albumin (BSA) in wash buffers to block non-specific binding sites.

- Pre-clear Lysate: Pre-incubate the cell lysate with bare beads or resin to remove proteins that bind non-specifically.

- Validate with Controls: Always include a control with a non-targeting antibody or bare beads to establish the baseline background signal.

Problem 2: Inefficient Capture of Polyubiquitinated Proteins

- Potential Cause: The abundance of the target polyubiquitinated protein is low, or the ubiquitin chains are being degraded by deubiquitinases (DUBs) during lysis.

- Solution:

- Use Proteasome Inhibitors: Treat cells with inhibitors like MG-132 (e.g., 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) prior to harvesting to stabilize ubiquitinated proteins [21].

- Incorporate DUB Inhibitors: Add broad-spectrum DUB inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide or PR-619) directly to the cell lysis buffer [2].

- Employ High-Affinity Binders: Utilize TUBEs, which have nanomolar affinity for polyubiquitin chains and can effectively shield them from DUB activity [18] [19].

- Increase Input Material: As a starting point, use 20 µL of agarose-TUBE beads or 100 µL of magnetic-TUBE slurry per milligram of cell extract [18].

Problem 3: Inability to Distinguish Between Linkage Types

- Potential Cause: The antibody or enrichment reagent has cross-reactivity with non-cognate ubiquitin linkages.

- Solution:

- Use Validated Linkage-Specific Reagents: Employ well-characterized tools like chain-selective TUBEs (e.g., K48-TUBE vs. K63-TUBE) or affimers that are designed for specific linkages [19] [20].

- Validate with Linkage-Defined Standards: Use well-defined ubiquitin chains (e.g., K48-only or K63-only Ub) in your experiments to confirm the specificity of your detection reagent [20].

- Combine Tools: Use a pan-specific TUBE for initial enrichment, followed by immunoblotting with a linkage-specific antibody to determine the chain type [21].

Problem 4: Smear Instead of Discrete Bands on Western Blot

- Potential Cause: This is often an expected result, as a heterogeneous mixture of ubiquitinated proteins and ubiquitin chains of varying lengths will appear as a smear.

- Solution:

- This is a Feature, Not a Bug: A smear indicates successful enrichment of a diverse population of polyubiquitinated proteins [21].

- Probe for Your Specific Target: After confirming ubiquitin enrichment, re-probe the membrane with an antibody against your protein of interest to identify a specific signal within the smear.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between a pan-TUBE and a linkage-specific TUBE? Pan-TUBEs (like TUBE1 and TUBE2) bind to all types of polyubiquitin linkages and are ideal for general enrichment and stabilization of ubiquitinated proteins. Linkage-specific TUBEs (e.g., for K48, K63, or M1) are engineered to bind with high affinity to only one specific linkage type, allowing you to investigate the function of that particular chain [18] [19].

Q2: My linkage-specific antibody isn't working in immunofluorescence. What can I do? Linkage-specific antibodies can sometimes perform differently between applications. Consider alternative reagent types that have been validated for imaging. For example, linkage-specific affimers and TUBEs conjugated to fluorophores (e.g., TAMRA, FITC) have been successfully used for confocal fluorescence microscopy [20].

Q3: How do I elute ubiquitinated proteins from TUBE beads for downstream analysis? For TUBE-based enrichments, it is recommended to use a proprietary elution buffer (e.g., LifeSensors Cat # UM411B) or a standard SDS-PAGE loading buffer for direct analysis by western blot. For subsequent mass spectrometry, gentle elution with a low-pH buffer or a solution of free ubiquitin peptide can be effective [18].

Q4: Can I use these tools to study atypical ubiquitin linkages like K6 or K27? Yes, the field is continuously evolving. While reagents for K48 and K63 are most common, linkage-specific tools for atypical chains are becoming available. For instance, K6-linkage-specific affimers have been developed and used to identify HUWE1 as a major E3 ligase for K6 chains [20]. However, commercial availability for all linkages may still be limited.

Experimental Workflow: Assessing Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination

The following diagram illustrates a robust protocol for using chain-specific TUBEs to analyze endogenous protein ubiquitination in a high-throughput format, such as a 96-well plate.

Workflow for TUBE-Based Ubiquitination Assay

Ubiquitin Signaling Pathways and Functional Outcomes

Understanding the functional context of different ubiquitin linkages is crucial for designing relevant experiments. The diagram below summarizes the primary cellular functions associated with the major ubiquitin chain types.

Primary Functions of Major Ubiquitin Linkages

Troubleshooting Guides

Probe Synthesis and Functionality

Problem: Low Yield or Failed Synthesis of Non-hydrolyzable Diubiquitin Probes

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Ligation | Inefficient copper-catalyzed alkyne-azide cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction. | Ensure proper removal of oxygen from the reaction mixture and use fresh catalysts. Confirm the integrity of azido-ornithine and propargylamide precursors [22]. | |

| Probe Assembly | Incorrect handling of C-terminal thioester intermediates during solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS). | Use chlorotrityl resin for SPPS and cleave the Ub1–75 precursor with 20% hexafluoro-isopropanol (HFIP) to expose the C-terminal carboxylic acid for proper activation [22]. | |

| Purification | Inadequate purification leading to side products. | Employ a two-step purification using reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to isolate pure probe [22]. |

Problem: Synthesized Ubiquitin Variant Lacks Biological Activity

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Integrity | The synthetic protein is misfolded or the triazole linkage disrupts native Ub structure. | Refold the protein post-synthesis using standard Ub refolding protocols. Verify folding and stability via circular dichroism (CD) or NMR [23] [22]. | |

| Warhead Reactivity | The C-terminal warhead (e.g., propargylamide) is inactive. | Test warhead reactivity using a control reaction with a known, active DUB. Synthesize a small batch of probe with a fluorescent tag (e.g., TAMRA) to confirm successful labeling [22]. | |

| Linkage Specificity | The designed linkage does not mimic the native isopeptide bond for target interaction. | Validate the probe using a DUB with known linkage specificity (e.g., use K48-linked probe for a proteasome-associated DUB) as a positive control [22]. |

Specificity and Background

Problem: High Non-Specific Binding in Affinity Enrichment Experiments

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Matrix | Non-specific interactions with the resin or tag (e.g., GST) used for the Ub variant. | Use a different immobilization chemistry or tag. Incorporate stringent wash steps with high salt (e.g., 300-500 mM NaCl) and non-ionic detergents before elution [23]. | |

| Cell Lysate | Endogenous ubiquitin and high-abundance proteins compete for binding. | Pre-clear lysate with bare resin/beads. Use cell lines treated with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., 5-25 µM MG-132 for 1-2 hours) to enrich for ubiquitinated proteins, but note potential cytotoxicity with overexposure [24]. | |

| Probe Concentration | The concentration of the immobilized Ub variant is too high, saturating specific sites and promoting off-target binding. | Titrate the amount of Ub variant conjugated to the beads. Use the minimal amount required for efficient pull-down to minimize non-specific interactions [23]. |

Problem: Probe Binds Non-Target Deubiquitylating Enzymes (DUBs)

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Design | The probe's warhead is too reactive and lacks selectivity. | Consider using a less reactive warhead or a full-length diUb probe that requires engagement of both S1 and S2 pockets for binding, which is specific to a smaller subset of DUBs [22]. | |

| Experimental Conditions | The reaction buffer or incubation time allows for non-specific reactivity. | Include control experiments with a probe lacking the warhead to identify non-covalent binders. Optimize incubation time and temperature to favor specific enzymatic turnover [22]. |

Detection and Analysis

Problem: Weak or No Signal in Mass Spectrometry After Enrichment

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Inefficient elution of bound proteins from the affinity matrix. | Use a competitive elution with high concentrations (e.g., 0.5-1 M) of free ubiquitin or a low-pH elution buffer. For downstream MS, use protocols optimized for on-bead digestion to minimize sample loss [24]. | |

| Ubiquitinylation Level | The endogenous levels of the target ubiquitinated proteins are too low. | Amplify the ubiquitination signal by treating cells with a proteasome inhibitor like MG-132 prior to harvesting, which prevents the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins [24]. | |

| MS Sensitivity | The enriched ubiquitinated peptides are suppressed by more abundant non-modified peptides. | Use a tandem enrichment strategy, such as SCASP-PTM, which allows for the sequential enrichment of ubiquitinated, phosphorylated, and glycosylated peptides from a single sample without intermediate desalting, thereby reducing sample loss and complexity [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using synthetic ubiquitin variants over enzymatically generated ones? Synthetic biology approaches, such as solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) and native chemical ligation (NCL), provide atomic-level control. This allows for the generation of homogeneously modified Ub variants that are often difficult or impossible to produce enzymatically in high purity. You can incorporate non-hydrolyzable linkages (e.g., triazole), site-specific post-translational modifications (PTMs), non-canonical amino acids, and stable isotopic labels with precision, which is crucial for detailed functional and structural studies [23] [25].

Q2: When should I choose a non-hydrolyzable diubiquitin probe over a monomeric Ub probe? The choice depends on the DUB's mechanism. Use monomeric Ub probes (targeting the S1 pocket) to identify DUBs that cleave monoUb or the distal end of chains. Use non-hydrolyzable diUb probes when you need to study DUBs that require engagement of additional binding pockets. Probes with a warhead between two Ub units (S1-S1' targeting) are good for DUBs that disassemble chains, while probes with a warhead at the C-terminus of the proximal Ub (S1-S2 targeting) are essential for studying DUBs that cleave at the proximal end of a chain, such as some viral DUBs or editors like OTUD2/3 [22].

Q3: My ubiquitin enrichment shows a smear on a western blot. Is this normal? Yes, this is typically expected and often indicates a successful enrichment. A smear represents the heterogeneous mixture of monomeric ubiquitin, polyubiquitin chains of different lengths and linkages, and ubiquitinated proteins of varying molecular weights captured by your method (e.g., using a Ubiquitin-Trap). To distinguish specific linkages within the smear, you must follow up with linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies during western blot analysis [24].

Q4: How can I confirm that my activity-based probe is functioning correctly? First, validate its reactivity with a positive control DUB known to be labeled by such probes (e.g., USP14 for diUb probes). Use fluorescently tagged probes (TAMRA) to visualize labeling by SDS-PAGE. For functional validation in a complex mixture, incubate the probe with cell lysate, followed by click chemistry addition of a biotin tag for enrichment and western blotting with streptavidin-HRP or avidin to confirm labeling of the expected protein targets [26] [22].

Q5: Can these chemical biology tools be applied to ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubls)? Absolutely. The same chemical synthesis principles have been successfully applied to study Ubls like SUMO, NEDD8, ISG15, and UFM1. These tools enable the generation of defined Ubl chains and Ubl-protein conjugates, which are equally challenging to obtain homogeneously through enzymatic methods. This allows for parallel exploration of the biology and crosstalk within the entire Ub/Ubl family [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents used in the synthesis and application of synthetic ubiquitin variants and non-hydrolyzable probes.

| Reagent Name | Function/Description | Key Application | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Agarose/Magnetic) | Anti-Ubiquitin nanobody (VHH) coupled to beads for immunoprecipitation of monoUb, Ub chains, and ubiquitinated proteins. | Pull-down of ubiquitinated proteins from complex cell lysates for detection or MS analysis. [24] | |

| Non-hydrolyzable DiUb Probes (with PA warhead) | Synthetic diubiquitin linked via triazole with a C-terminal propargylamide warhead. Covalently traps DUBs engaging S1 and S2 pockets. | Identifying and characterizing linkage-specific DUB activity in lysates or with purified enzymes. [22] | |

| Ub-MES / UbFluor | Ubiquitin C-terminus conjugated to mercaptoethanesulfonate. Allows E3~Ub complex formation without E1/E2/ATP. Fluorogenic version for HTS. | High-throughput screening for inhibitors of HECT-family E3 ligases like PARKIN. [26] | |

| Azido-ornithine | A non-canonical amino acid incorporated during SPPS to provide an azide group for click chemistry. | Serves as the "anchor" point in the proximal Ub for copper-catalyzed cycloaddition to form triazole-linked chains. [22] | |

| Propargylamine (PA) | A warhead containing an alkyne group. | Used as the C-terminal reactive group on Ub to covalently modify the catalytic cysteine of DUBs. Also used in click chemistry. [22] |

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Probe Synthesis Workflow

Affinity Enrichment Logic

DUB Profiling Pathway

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Ubiquitin Enrichment

Problem: High Background and Non-Specific Binding

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Lysate Clearing | Centrifuge lysate at 20,000g for 10 min at 4°C before enrichment [27]. | Removes particulate debris that can trap proteins non-specifically. |

| Insufficient Washing | Increase number of wash steps; use stringent wash buffers (e.g., containing 0.5% NP-40) [28]. | Removes weakly associated, non-specifically bound proteins. |

| Antibody Leakage (Agarose) | Use covalently cross-linked antibodies or magnetic bead-conjugated reagents [27]. | Prevents antibody heavy/light chains from leaching and appearing in MS samples. |

| Non-Optimal Bead Type | Switch to magnetic bead-based platforms (e.g., HS mag anti-K-ε-GG) for more efficient washing [27]. | Magnetic particle processors reduce handling and improve wash consistency. |

Problem: Low Yield of Ubiquitinated Proteins/Peptides

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Deubiquitination | Add Deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors (e.g., 5-50 μM PR-619, 1-5 mM N-Ethylmaleimide) to lysis buffer [27] [28]. | Preserves the labile ubiquitin modification during sample preparation. |

| Proteasomal Degradation | Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., 1-25 μM MG-132) for 1-2 hours before harvesting [29] [28]. | Stabilizes ubiquitinated proteins destined for degradation. |

| Insufficient Input Material | Use recommended input (e.g., 500 μg peptide for UbiFast); avoid over-dilution [27]. | Ensures target ubiquitinated species are above the detection limit. |

| Inefficient Elution | Use low-pH elution buffer or directly elute in SDS-PAGE loading buffer for western blot [29]. | Disrupts strong antibody-antigen or UBD-ubiquitin interactions. |

Problem: Inability to Detect Specific Ubiquitin Linkages

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Using Pan-Specific Reagents | Employ linkage-specific tools (e.g., K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE) for targeted enrichment [12]. | Specific reagents selectively capture the ubiquitin topology of interest. |

| Lack of Downstream Specificity | Follow pan-specific enrichment with western blot using linkage-specific antibodies [29]. | Confirms the identity of the captured ubiquitin chain linkage. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the major advantages of automated magnetic bead systems over manual agarose-based methods?

Automation with magnetic beads offers significant performance improvements. A study comparing the automated UbiFast method using magnetic beads to the manual method reported a drastic reduction in processing time from a manual protocol to approximately 2 hours for a 10-plex sample, enabling processing of up to 96 samples in a single day. Furthermore, automation led to a major increase in reproducibility and significantly reduced variability across process replicates. Notably, the depth of coverage was also enhanced, with the automated method identifying approximately 20,000 ubiquitylation sites from a single experiment [27].

Q2: My goal is to profile ubiquitination sites by mass spectrometry. Should I enrich at the protein or peptide level?

For mass spectrometry-based ubiquitin site mapping (identifying the specific lysine residue modified), enrichment at the peptide level using K-ε-GG antibodies is the established method. Trypsin digestion cleaves ubiquitin, leaving a diagnostic di-glycine (GG) remnant on the modified lysine of the substrate peptide. Anti-K-ε-GG antibodies specifically enrich these peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis, allowing precise site identification [27] [30]. For studying protein-level interactions or complexes, protein-level enrichment with tools like TUBEs or Ubiquitin-Traps is more appropriate [29].

Q3: How can I specifically study K48-linked or K63-linked polyubiquitination in my sample?

You require tools with linkage specificity. Chain-specific Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) are engineered for this purpose. For example:

- K48-TUBEs selectively capture proteins modified with K48-linked chains, which are primarily associated with proteasomal degradation [12].

- K63-TUBEs selectively capture proteins modified with K63-linked chains, which are involved in inflammatory signaling and other non-degradative functions [12].

A recent study demonstrated this by using K63-TUBEs to capture L18-MDP-induced K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2, while K48-TUBEs captured RIPK2 PROTAC-induced K48 ubiquitination [12].

Q4: What is the difference between TUBEs and the Ubiquitin-Trap?

Both are affinity tools, but they use different capture mechanisms:

- TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities): These are engineered proteins containing multiple ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) that bind non-covalently to polyubiquitin chains. They can protect chains from deubiquitination and some are available with linkage specificity (e.g., for K48 or K63) [12].

- Ubiquitin-Trap: This reagent uses an anti-ubiquitin nanobody (VHH) coupled to beads to immunoprecipitate ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins. It is linkage-independent and can capture monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitinated proteins [29].

Q5: Can I study unanchored (free) polyubiquitin chains, and why are they important?

Yes, this requires specific tools. Unanchored polyubiquitin chains (not attached to a substrate protein) are biologically significant in processes like innate immune signaling and proteasome regulation. They can be specifically enriched using a Free Ubiquitin-Binding Entity (FUBE), such as the Znf-UBP domain from USP5, which has high specificity for the free C-terminus of ubiquitin [28]. These chains accumulate when the 26S proteasome is pharmacologically inhibited [28].

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Enrichment Methods

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies for different enrichment strategies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Ubiquitin Enrichment Methods

| Enrichment Method | Reported Scale / Throughput | Key Performance Metrics | Specificity Claims | Application Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated UbiFast (magnetic beads) [27] | ~20,000 ubiquitylation sites from a TMT10-plex; 96 samples/day. | High reproducibility; ~2h processing for 10-plex; Reduced variability vs. manual. | K-ε-GG antibody for ubiquitin remnant motif (site-specific). | Deep-scale ubiquitin site mapping for large sample sets (e.g., PDX tissue). |

| Chain-Specific TUBEs [12] | Applied in 96-well plate HTS format for endogenous target ubiquitination. | Can differentiate context-dependent ubiquitination (e.g., K48 vs. K63 on RIPK2). | High affinity for specific polyubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48 or K63). | Investigating linkage-specific functions in signaling or PROTAC mechanism. |

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Nanobody) [29] | Validated for IP from human, mouse, hamster, dog, plant, and yeast cells. | Fast, easy pulldowns; stable under harsh washing conditions; low background. | Linkage-independent; binds monomeric ubiquitin, polymers, ubiquitinated proteins. | General ubiquitin immunoprecipitation and protein-level interaction studies. |

| Pierce Ubiquitin Enrichment Kit [7] [31] | Processes 1 to 15 samples concurrently. | <45 minutes hands-on time; compatible with standard cell lysis products. | Anti-ubiquitin affinity resin; purifies polyubiquitinated proteins. | Western blot analysis of polyubiquitinated proteins from cells and tissues. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitin Enrichment Research

| Reagent / Kit | Core Function | Brief Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| HS mag anti-K-ε-GG [27] | Peptide-level enrichment for site mapping. | Magnetic bead-conjugated antibody enriches tryptic peptides with di-glycine (GG) remnant on lysine. |

| TUBEs (Pan & Chain-Specific) [12] | Protein-level enrichment of polyubiquitin. | Engineered tandem ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains. |

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Agarose/Magnetic) [29] | General-purpose ubiquitin immunoprecipitation. | Anti-ubiquitin nanobody (VHH) coupled to beads captures ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins. |

| FUBE (Znf-UBP domain) [28] | Specific isolation of unanchored polyubiquitin. | UBD from USP5 selectively binds the free C-terminus of unconjugated ubiquitin and unanchored chains. |

| DUB & Proteasome Inhibitors [27] [29] | Preservation of ubiquitin signals. | PR-619 (DUB inhibitor) and MG-132 (proteasome inhibitor) prevent loss of ubiquitination during processing. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Ubiquitin Enrichment Workflow Selection

Linkage Specific Ubiquitin Signaling

The following diagram outlines the core BioE3 strategy, which uses proximity-dependent biotinylation to label and isolate ubiquitinated substrates of a specific E3 ligase with high specificity [32].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

This protocol details the BioE3 method for identifying bona fide substrates of a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase, significantly reducing non-specific background [32].

Step 1: Cell Line Engineering and Preparation

- Generate stable cell line: Create a HEK293FT or U2OS cell line with a doxycycline (DOX)-inducible lentiviral vector expressing the

bioGEFUbconstruct. ThebioGEFtag is a mutated AviTag (WHE sequence mutated to GEF) with lower affinity for BirA, which is crucial for minimizing non-specific biotinylation [32]. - Culture in biotin-depleted media: Grow the stable cells in media supplemented with dialyzed, biotin-depleted serum for at least 24 hours prior to the experiment. This step is critical to deplete endogenous biotin and reduce background [32].

- Introduce BirA-E3 fusion: Transfect the cells with your plasmid encoding the

BirA-E3fusion protein. BirA can be fused to the N- or C-terminus of the E3 ligase, but N-terminal fusions are often used to avoid steric hindrance with the C-terminal RING domain [32].

Step 2: Induction, Labeling, and Substrate Capture

- Induce expression: Add doxycycline (DOX) to the culture medium for 24 hours. This simultaneously induces the expression of both

bioGEFUband theBirA-E3fusion protein [32]. - Pulse with biotin: Add exogenous biotin to the culture medium for a short, defined period (e.g., 2 hours). The limited time window ensures that only