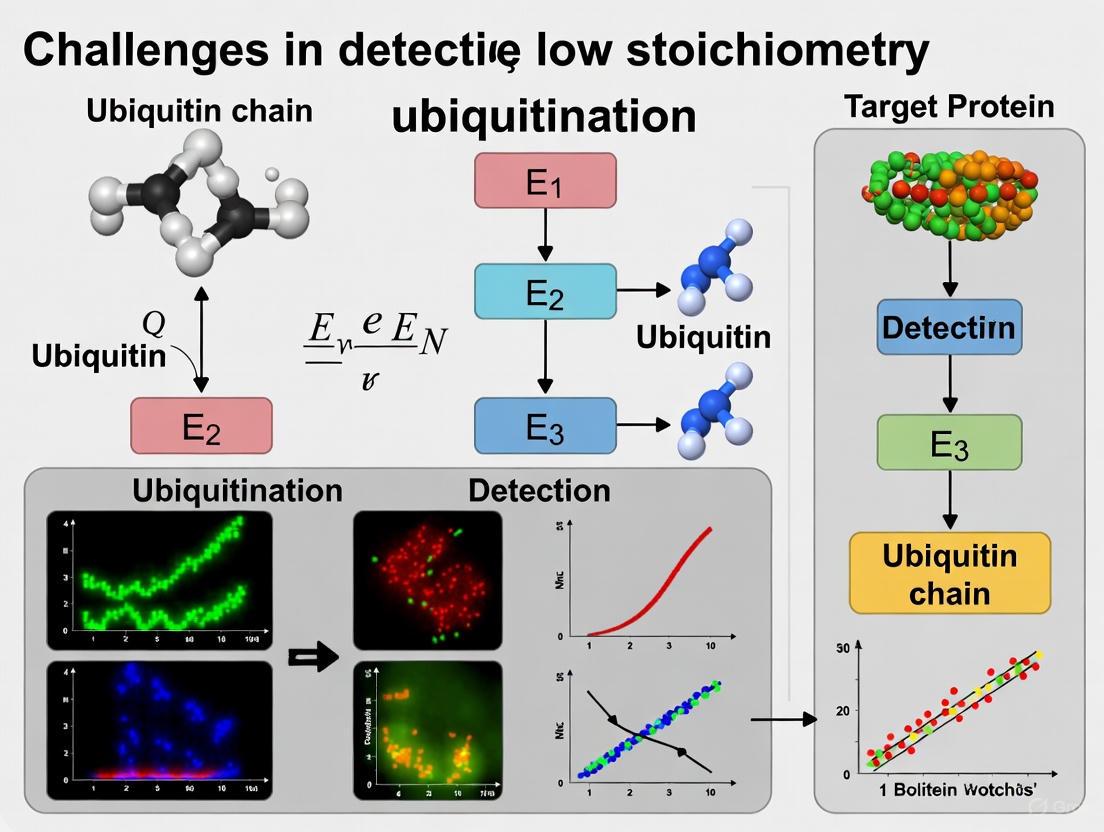

Overcoming Low Stoichiometry: Advanced Strategies for Ubiquitination Detection in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review addresses the significant analytical challenge of detecting protein ubiquitination at low stoichiometry, a fundamental post-translational modification with critical roles in cellular regulation and disease pathogenesis.

Overcoming Low Stoichiometry: Advanced Strategies for Ubiquitination Detection in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the significant analytical challenge of detecting protein ubiquitination at low stoichiometry, a fundamental post-translational modification with critical roles in cellular regulation and disease pathogenesis. We explore the foundational principles of ubiquitin biology and the technical barriers posed by the dynamic, transient nature of ubiquitination events. The article provides a detailed examination of current methodological approaches including mass spectrometry-based proteomics, high-throughput biochemical assays, and computational prediction tools. For researchers and drug development professionals, we offer practical troubleshooting guidance for assay optimization and a comparative analysis of validation strategies to ensure data reliability. By integrating insights from recent technological advances across these domains, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively capture and characterize ubiquitination events despite their low abundance, thereby accelerating discovery in basic research and therapeutic development.

The Ubiquitination Detection Challenge: Understanding Low Stoichiometry and Biological Complexity

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually all aspects of cellular function, from protein degradation to signal transduction. However, researchers consistently face a fundamental obstacle: the exceptionally low stoichiometry of this modification. Recent quantitative studies reveal that ubiquitylation site occupancy spans over four orders of magnitude, with the median ubiquitylation site occupancy being three orders of magnitude lower than that of phosphorylation [1]. This means that at any given moment, only a tiny fraction of a target protein exists in its ubiquitinated form, creating substantial detection challenges.

This low stoichiometry arises from the dynamic and transient nature of ubiquitination, the efficiency of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), and the rapid degradation of ubiquitinated substrates by the proteasome. Consequently, standard detection methods often fail to capture these elusive modifications, requiring specialized methodologies and troubleshooting approaches outlined in this technical support guide.

Key Concepts: Understanding Ubiquitination Complexity

FAQ: What makes ubiquitination so difficult to detect compared to other post-translational modifications?

Ubiquitination presents unique detection challenges due to several factors:

- Extremely Low Stoichiometry: The proportion of ubiquitinated molecules at any specific site is remarkably small, with median occupancy approximately 1000 times lower than phosphorylation [1]

- Structural Diversity: Ubiquitination can form multiple chain types (K48, K63, M1, etc.) with different functions, requiring linkage-specific detection methods [2]

- Transient Nature: The modification is highly dynamic due to active deubiquitination and rapid degradation of targets

- Technical Limitations: Standard immunoassays lack the sensitivity and specificity to detect these rare events without enrichment strategies

FAQ: Why does low stoichiometry matter for experimental outcomes?

Low stoichiometry directly impacts experimental detectability and interpretation:

- False Negatives: Genuine ubiquitination events go undetected due to insufficient sensitivity

- Enrichment Requirements: Direct detection without enrichment becomes impossible for most targets

- Signal Dilution: The ubiquitination signal is drowned out by the abundant unmodified protein population

- Quantification Challenges: Accurate measurement of modification extent requires specialized normalization approaches

Quantitative Landscape of Ubiquitination Stoichiometry

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings that highlight the stoichiometry challenge in ubiquitination research:

Table 1: Quantitative Measurements of Ubiquitination Stoichiometry

| Parameter | Value | Experimental Basis | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occupancy vs. Phosphorylation | >3 orders of magnitude lower | Global, site-resolved analysis [1] | Explains why ubiquitination is harder to detect than phosphorylation |

| Occupancy Range | Spans over 4 orders of magnitude | Quantitative proteomics [1] | Indicates enormous variation between different sites |

| High vs. Low Occupancy Sites | Distinct biological properties | Systems-scale quantification [1] | Suggests functional differences between high and low occupancy sites |

| Aging Brain Impact | 29% of sites altered independently of protein abundance | Mouse brain ubiquitylome analysis [3] | Demonstrates true stoichiometry changes in biological processes |

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

Enrichment-Based Detection Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the strategic approach to overcoming low stoichiometry through targeted enrichment:

TUBE-Based Enrichment Protocol

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) provide a powerful solution for ubiquitin enrichment:

Principle: TUBEs consist of multiple ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains engineered in tandem, creating nanomolar affinity for polyubiquitin chains while protecting them from deubiquitinating enzymes [2] [4].

Detailed Protocol:

Cell Lysis with DUB Inhibition

- Use semi-denaturing lysis conditions with 4M urea

- Include 20mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit cysteine-based DUBs

- Add protease inhibitor cocktails (EDTA-free recommended)

- Maintain samples at 4°C throughout processing [4]

TUBE-Bead Preparation

- Immobilize site-specifically biotinylated TUBEs on magnetic streptavidin beads

- Prepare fresh TUBE-bead assemblies before each experiment

- Use 10-50μg TUBE reagent per mg of cellular protein [4]

Enrichment Procedure

- Incubate lysate with TUBE-beads for 2-4 hours at 4°C with rotation

- Wash with urea-containing buffers to remove non-specifically bound proteins

- Elute with acidic conditions (pH 2.0-2.5) to liberate ubiquitinated proteins while retaining TUBE on beads [4]

Downstream Analysis

- Process eluates for immunoblotting with specific antibodies

- For MS analysis, proceed with tryptic digestion and LC-MS/MS

- For high-throughput applications, use TUBE-coated microplates [2]

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If background is high: Increase urea concentration in wash buffers

- If yield is low: Verify DUB inhibition by spiking recombinant triubiquitin chains

- If specificity is poor: Include control beads without TUBEs

- For linkage-specific analysis: Use chain-selective TUBEs (K48- or K63-specific) [2]

Mass Spectrometry-Based Detection Workflow

For researchers opting for MS-based detection, the following workflow addresses stoichiometry challenges:

Critical MS Parameters:

- Intensity: Measure of peptide abundance, influenced by protein abundance and ionization efficiency [5]

- Peptide Count: Number of different detected peptides from the same protein [5]

- Coverage: Proportion of protein covered by detected peptides (aim for 40-80% in purified samples) [5]

- Q-value: Statistical significance measure, should be <0.05 [5]

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key reagents for overcoming low stoichiometry challenges in ubiquitination research:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Detection

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TUBEs | Pan-selective TUBEs, K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs | Nanomolar affinity, DUB protection, linkage-specific options [2] [4] | Enrichment for immunoblotting, MS, HTS assays |

| Tagged Ubiquitin | His-Ub, Strep-Ub, HA-Ub | Affinity purification, expression in cells [6] | Identification of ubiquitination sites and substrates |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific | Recognize specific ubiquitin chain linkages [6] | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, enrichment |

| DUB Inhibitors | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), PR-619 | Preserve ubiquitin signals during processing [4] | Cell lysis, stabilization of ubiquitinated proteins |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Carfilzomib, MG132 | Stabilize degradative ubiquitination signals [4] | Accumulation of K48-linked ubiquitinated substrates |

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

PROTAC and Targeted Protein Degradation Analysis

The emergence of PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) has highlighted the need for precise ubiquitination detection:

Challenge: PROTACs induce highly specific, but low stoichiometry ubiquitination of target proteins, requiring sensitive detection methods to validate mechanism of action [2] [4].

Solution: Chain-specific TUBE-based assays can differentiate between degradative (K48-linked) and non-degradative (K63-linked) ubiquitination induced by different compounds [2].

Case Study: RIPK2 ubiquitination analysis demonstrated that inflammatory stimulus L18-MDP induced K63-linked chains captured by K63-TUBEs, while a RIPK2 PROTAC induced K48-linked chains captured by K48-TUBEs [2].

Detection of Non-Proteinaceous Ubiquitination

Recent research has revealed an expanded substrate realm for ubiquitination:

Novel Finding: The ubiquitin ligase HUWE1 can ubiquitinate drug-like small molecules containing primary amino groups, not just proteins [7]. This represents a new frontier in ubiquitination research with implications for drug metabolism and development.

Detection Method: Compound ubiquitination was detected using MS/MS analyses following in vitro ubiquitination reactions, identifying Ub C-terminal peptides modified with compound masses [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Problems

FAQ: Why are my ubiquitination signals weak even after enrichment?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incomplete DUB Inhibition: Increase NEM concentration to 20mM and include additional DUB inhibitors [4]

- Protein Degradation: Use EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktails and maintain samples at 4°C [5]

- Insufficient Enrichment: Scale up TUBE quantity or increase incubation time [2]

- Suboptimal Lysis Conditions: Implement semi-denaturing conditions with 4M urea [4]

- Proteasomal Degradation: Pre-treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., Carfilzomib) to preserve ubiquitinated species [4]

FAQ: How can I distinguish between genuine ubiquitination and background signals?

Validation Strategies:

- Control Enrichments: Include parallel samples with control beads without ubiquitin-binding entities [4]

- Genetic Validation: Express tagged ubiquitin and compare with endogenous detection [6]

- Site Mutation: Mutate putative ubiquitination sites (lysine to arginine) to confirm specificity [6]

- Multiple Methods: Confirm findings with orthogonal methods (e.g., TUBE enrichment + immuno-blotting) [2]

- Enzymatic Validation: Treat samples with deubiquitinases to demonstrate signal reversal [6]

FAQ: What are the best practices for sample preparation to preserve ubiquitination?

Critical Steps for Success:

- Rapid Processing: Process samples immediately after collection [5]

- Temperature Control: Maintain samples at 4°C during all steps [5]

- Comprehensive Inhibition: Use both protease and DUB inhibitors in all buffers [4]

- Avoid Autoclaving: Use HPLC-grade water and avoid detergents that interfere with MS [5]

- Quality Control: Monitor each step by Western blot or Coomassie staining [5]

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field continues to evolve with new methodologies addressing the stoichiometry challenge:

- Improved TUBE Technologies: Development of higher affinity binders and additional linkage-specific reagents [2]

- Integrated Multi-omics Approaches: Combining ubiquitinomics with proteomics and transcriptomics [3]

- Single-Cell Ubiquitinomics: Adapting methods for single-cell resolution [1]

- Spatial Ubiquitinomics: Mapping ubiquitination within cellular compartments [3]

- Chemical Biology Tools: Developing activity-based probes for specific E3 ligases and DUBs [7]

As these technologies mature, they will progressively overcome the fundamental problem of low stoichiometry, making ubiquitination less elusive and enabling deeper understanding of its crucial biological functions.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular functions, including protein degradation, activity, and localization. This process involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a small 76-amino acid protein, to substrate proteins. The versatility of ubiquitination stems from its ability to create various ubiquitin architectures—from a single ubiquitin (monoubiquitination) to complex chains (polyubiquitination)—each with distinct cellular functions [8] [9].

FAQs: Core Concepts in Ubiquitin Biology

What is the fundamental enzymatic cascade governing ubiquitination? The ubiquitination process involves a sequential three-enzyme cascade:

- E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner

- E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme): Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1

- E3 (ubiquitin ligase): Facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the specific substrate protein

This hierarchical system, with approximately 2 E1s, 40 E2s, and over 600 E3s in humans, allows for precise regulation and substrate specificity [8] [9].

How does monoubiquitination differ functionally from polyubiquitination?

- Monoubiquitination: Involves attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to a substrate, primarily regulating endocytic trafficking, protein-protein interactions, and subcellular localization [9].

- Polyubiquitination: Features chains of ubiquitin molecules linked through specific lysine residues, with K48-linked chains predominantly targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains typically regulate signaling pathways and protein interactions without degradation [8] [9].

Why is detecting low-stoichiometry ubiquitination events so challenging? The identification of protein ubiquitination sites presents significant challenges due to:

- Low stoichiometry of ubiquitinated proteins compared to the global proteome

- Dynamic and reversible nature of ubiquitination, balanced by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs)

- Complexity of ubiquitin chains with variations in length, linkage types, and architecture

- Technical limitations in enriching low-abundance ubiquitinated species from complex protein mixtures [10] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges in Ubiquitination Detection

Challenge: Inefficient Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Substrates

Table 1: Comparison of Ubiquitin Enrichment Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Tagging (His/Strep) | Expression of tagged ubiquitin in cells | Easy implementation; relatively low cost | Potential structural artifacts; infeasible for patient tissues | Screening ubiquitinated substrates in cell lines [6] |

| Antibody-Based Enrichment | Use of anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) | Works with endogenous ubiquitin; applicable to tissues | High cost; potential non-specific binding; sequence bias | Physiological conditions and clinical samples [10] [6] |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs) | Utilization of proteins with natural ubiquitin affinity | Linkage-specific options available | Low affinity of single UBDs | Enrichment of specific ubiquitin chain types [6] |

| Antibody-Free Chemical Methods (AFUP) | Selective chemical labeling of ubiquitination sites | Avoids antibody limitations; excellent reproducibility | Requires specialized chemical expertise | Novel ubiquitination site discovery; quantitative studies [10] |

Solution: Implement the AFUP (Antibody-Free approach for Ubiquitination Profiling) method, which involves:

- Blocking all free amino groups with formaldehyde at the protein level

- Hydrolyzing ubiquitin chains using deubiquitinases (USP2 and USP21) to generate free lysine ε-NH₂ at ubiquitination sites

- Chemically labeling the liberated amines with NHS-SS-Biotin reagents

- Enriching labeled peptides using Streptavidin Sepharose

- Analyzing eluted peptides by LC-MS/MS [10]

This approach identified 349 ± 7 ubiquitination sites from 0.8 mg of HeLa proteins with excellent reproducibility (CV = 0.2%) and high quantitative stability (Pearson, r ≥ 0.91) [10].

Challenge: Differentiating Between Priming and Elongation in Polyubiquitination

Solution: Employ the "apyrase chase" strategy to uncouple priming from chain elongation:

- Set up reconstituted ubiquitination systems with priming E2 (UbcH5c) and elongating E2 (Cdc34b)

- Pre-assemble E3-substrate complexes

- Add apyrase (a potent ATP hydrolase) to deplete ATP and prevent new E2-Ub thioester formation

- Monitor decay rates of ubiquitinated substrates with defined chain lengths [11]

This approach revealed that UbcH5c-Ub thioester complexes are highly unstable (>93% disappearance within 1 minute), while Cdc34b-Ub complexes are relatively stable (24% remaining after 20 minutes), enabling temporal separation of priming and elongation events [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| E2 Enzymes (UbcH5c) | Priming monoubiquitination | Forms unstable thioester complexes with ubiquitin | Essential for initial substrate modification [11] |

| E2 Enzymes (Cdc34b) | Ubiquitin chain elongation | Forms stable thioester complexes; processive chain extension | Critical for polyubiquitin chain formation [11] |

| Reconstituted CRL Systems (CRL4CRBN, SCFβTrCP) | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Modular E3 ligase systems with defined substrates | Enable mechanistic studies of specific E3-substrate pairs [11] |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detection of specific polyubiquitin chains | Recognize K48, K63, K11, etc. linkages | Essential for determining chain topology and function [6] |

| Deubiquitinases (USP2cc, USP21) | Ubiquitin removal in AFUP method | Broad linkage specificity | Generate free amines at ubiquitination sites for chemical labeling [10] |

| NHS-SS-Biotin Reagents | Chemical labeling in AFUP approach | Selective reaction with primary amines | Enables streptavidin-based enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides [10] |

Methodologies for Comprehensive Ubiquitination Analysis

Advanced Mass Spectrometry Approaches

Modern proteomic strategies have significantly advanced ubiquitination profiling:

- Di-Glycine Remnant Detection: Trypsin cleavage of ubiquitin-conjugated substrates leaves a characteristic di-glycine signature on modified lysines, detectable by MS as a 114.04 Da mass shift [8] [6].

- StUbEx PLUS System: Utilizes His-tagged ubiquitin inserted between serine 65 and threonine 66, though this may introduce structural artifacts [10].

- Ubiquitin COFRADIC: Involves blocking all primary amino groups, USP2cc-mediated ubiquitin removal, and introduction of hydrophobic groups for enrichment—highly specific but time-consuming [10].

Quantitative Profiling of Ubiquitination Dynamics

For studying ubiquitination dynamics in biological contexts:

- Combine AFUP with basic C18 pre-fractionation to identify >7,000 ubiquitination sites

- Normalize based on protein abundance to account for expression changes

- Apply statistical analysis to identify significantly regulated sites (e.g., 209 ubiquitination sites were significantly regulated in UBE2O knockdown cells) [10]

Visualization of Key Concepts

Ubiquitin Enzymatic Cascade and Priming-Elongation Mechanism

Detection Strategies for Low-Stoichiometry Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination is a critical yet complex post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes, from protein degradation to signal transduction. Researchers face three fundamental technical hurdles when studying this system: the dynamic nature of modifications with rapid turnover, the exceptionally low stoichiometry at most sites, and the immense structural diversity of ubiquitin chains. The median ubiquitination site occupancy is three orders of magnitude lower than that of phosphorylation, spanning over four orders of magnitude across the proteome [1]. This combination of factors makes specific, sensitive detection of ubiquitination events particularly challenging. Recent advances in affinity-based enrichment tools and high-throughput detection platforms are now providing solutions to these long-standing problems, enabling more precise analysis of ubiquitination in both basic research and drug discovery contexts like PROTAC development.

Researcher FAQs: Addressing Fundamental Ubiquitination Questions

What makes ubiquitination detection so challenging compared to other post-translational modifications? Ubiquitination presents unique detection challenges due to three interconnected properties: (1) Extremely low stoichiometry - site occupancy is typically 1000-fold lower than phosphorylation, with the median site modified on only a tiny fraction of protein molecules [1]; (2) Rapid turnover - ubiquitination is highly dynamic, with most modifications rapidly removed by deubiquitinases or leading to proteasomal degradation; (3) Structural diversity - eight distinct ubiquitin chain linkages (M1, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) create a complex landscape of potential signals with different biological functions [2].

How can I specifically detect K48 vs. K63 ubiquitin linkages in my protein of interest? Chain-specific TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) enable selective capture of different ubiquitin chain types. For example, K63-TUBEs specifically capture RIPK2 when stimulated with L18-MDP (inducing K63-linked chains), while K48-TUBEs capture RIPK2 when treated with a PROTAC degrader (inducing K48-linked chains) [2]. Pan-selective TUBEs capture all chain types but don't distinguish between them. The choice between these tools depends on whether your research question requires linkage-specific information or global ubiquitination assessment.

What methods are available for high-throughput screening of ubiquitination in PROTAC development? ThUBD (Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain)-coated 96-well plates provide an unbiased, high-affinity platform for high-throughput ubiquitination detection. This system captures proteins modified with all ubiquitin chain types and demonstrates a 16-fold wider linear range for capturing polyubiquitinated proteins compared to TUBE-coated plates [12] [13]. The method enables efficient quantification of ubiquitination signals from complex proteome samples, supporting PROTAC characterization and screening.

How does rapid turnover of ubiquitination affect experimental outcomes? The rapid turnover of ubiquitination means that conventional lysis methods often miss transient modifications. To preserve ubiquitination signals, lysis buffers must include deubiquitinase inhibitors (such as N-ethylmaleimide or PR-619) and be optimized to quickly inactivate cellular enzymes [2]. The half-life of ubiquitination varies significantly between sites, with those in structured protein regions exhibiting longer half-lives than those in unstructured regions [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or no ubiquitination signal | Low stoichiometry of modification; Inefficient enrichment; Sample degradation | Use high-affinity capture reagents (ThUBD/OtUBD); Increase input material; Add fresh DUB inhibitors to lysis buffer [12] [14] |

| Inability to distinguish ubiquitin linkages | Use of pan-specific detection methods only | Employ chain-specific TUBEs (K48-selective, K63-selective); Validate with linkage-specific controls [2] |

| High background in detection | Non-specific binding; Incomplete washing | Optimize wash buffer stringency (increase salt, add mild detergent); Include specific blocking agents [12] |

| Poor reproducibility between experiments | Variable lysis conditions; Protease/DUB activity variations | Standardize lysis protocol precisely; Use fresh inhibitors; Process controls in parallel [2] [14] |

| Inconsistent results between techniques | Technical biases of different methods | Correlate mass spectrometry data with affinity enrichment; Use orthogonal validation methods [12] [2] |

Advanced Troubleshooting: Addressing Specific Scenarios

Challenge: Preserving Linkage-Specific Signals in Cellular Assays When studying specific biological contexts like inflammatory signaling (which often involves K63 linkages) or PROTAC-induced degradation (K48 linkages), maintaining the integrity of these specific chains is essential. Pre-treat cells with linkage-specific deubiquitinase inhibitors when available. For K63-linked chain analysis, validate your system with known positive controls like L18-MDP-stimulated RIPK2 in THP-1 cells [2]. For PROTAC studies, include a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132) if measuring cumulative ubiquitination rather than turnover rate.

Challenge: Detecting Ubiquitination on Low-Abundance Proteins For proteins with inherently low abundance or very low modification stoichiometry, standard enrichment methods may yield insufficient material. Consider using the OtUBD affinity resin, which exhibits low nanomolar affinity for ubiquitin and can enrich both mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins effectively [14]. Combine denaturing and native purification workflows to distinguish directly ubiquitinated proteins from interactors.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ubiquitin Detection Technologies

| Technology | Affinity/Sensitivity | Linkage Bias | Throughput Capacity | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThUBD-coated plates | 5 pmol polyUb chain capacity [12] | Unbiased to all chain types [13] | 96-well HTS format [12] | Global ubiquitination profiling, PROTAC screening |

| TUBE-based assays | Lower than ThUBD [12] | Variable by TUBE type [2] | 96-well format [2] | Linkage-specific applications |

| OtUBD affinity resin | Low nM range Kd [14] | Binds mono- and polyUb [14] | Low to medium | Proteomics sample preparation |

| Antibody-based methods | Highly variable | Often linkage-biased [12] | Medium (ELISA) | Target-specific assays |

Table 2: Key Ubiquitination Properties Affecting Detection

| Property | Quantitative Value | Experimental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Median site occupancy | ~1000x lower than phosphorylation [1] | Requires highly sensitive enrichment methods |

| Occupancy range | Spans >4 orders of magnitude [1] | Dynamic range of detection must be wide |

| Response to proteasome inhibition | Strong upregulation for degradation-targeted sites [1] | Can be used to distinguish degradation signals |

| Half-life in structured regions | Longer than unstructured regions [1] | Affects required time resolution for capture |

Ubiquitination Detection Workflow Strategy

Essential Protocols for Overcoming Key Hurdles

Protocol: ThUBD-Coated Plate Ubiquitination Detection

Purpose: High-throughput, unbiased quantification of global ubiquitination signals or target-specific ubiquitination.

Materials:

- ThUBD-coated 96-well plates (Corning 3603 type) [12]

- Coating buffer: PBS or appropriate carbonate buffer

- Wash buffer: PBS with 0.1% Tween-20

- Blocking buffer: 3-5% BSA in PBS

- Detection antibody: Anti-target protein antibody or ThUBD-HRP

- Lysis buffer with DUB inhibitors (20mM N-ethylmaleimide, 1μM PR-619)

Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Coat plates with 1.03μg ± 0.002 of ThUBD per well. Confirm binding capacity of ~5 pmol of polyubiquitin chains [12].

- Sample Preparation: Lyse cells in optimized buffer (including DUB inhibitors) to preserve ubiquitination. Pre-clear lysates if necessary.

- Incubation: Add samples to wells and incubate 2 hours at 4°C with gentle shaking.

- Washing: Wash 3-5 times with wash buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Detection: Incubate with primary antibody against target protein, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, or use ThUBD-HRP for global ubiquitination detection.

- Quantification: Develop with appropriate substrate and measure signal.

Troubleshooting Notes: For low-abundance targets, increase incubation time to 4 hours. If background is high, increase salt concentration (up to 300mM NaCl) in wash buffer.

Protocol: Chain-Specific Ubiquitination Analysis Using TUBEs

Purpose: To specifically detect and quantify K48 or K63-linked ubiquitination on endogenous proteins.

Materials:

- Chain-specific TUBEs (K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, Pan-TUBE)

- Coated plates or magnetic beads

- Stimuli: L18-MDP (for K63 signaling) or PROTAC (for K48 degradation)

- Cell lines: THP-1 (for inflammation models) or appropriate PROTAC-responsive lines

Procedure:

- Cellular Stimulation: For K63 analysis: treat THP-1 cells with 200-500 ng/ml L18-MDP for 30 minutes. For K48 analysis: treat with appropriate PROTAC concentration for designated time [2].

- Inhibition Controls: Pre-treat with specific inhibitors (e.g., Ponatinib for RIPK2) to confirm signal specificity.

- Lysis and Enrichment: Lyse cells in TUBE-compatible buffer and incubate with chain-specific TUBEs.

- Target Detection: Detect bound target protein by immunoblotting with specific antibodies.

- Validation: Use multiple TUBE types in parallel to confirm linkage specificity.

Application Example: This protocol successfully demonstrated that L18-MDP stimulates K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2 captured by K63-TUBEs, while RIPK2 PROTAC-induced ubiquitination was captured by K48-TUBEs [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains | ThUBD, TUBEs, OtUBD | High-affinity capture of ubiquitinated proteins from complex mixtures [12] [2] [14] |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), PR-619 | Preserve ubiquitination signals during sample preparation by inhibiting DUB activity [14] |

| Chain-Specific Tools | K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE | Selective enrichment of linkage-specific ubiquitination events [2] |

| Detection Systems | ThUBD-coated 96-well plates, TUBE-based assays | High-throughput quantification of ubiquitination signals [12] [2] |

| Positive Controls | L18-MDP, PROTACs | Induce specific ubiquitination types for assay validation [2] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib | Accumulate degradation-targeted ubiquitinated proteins [1] |

Research Reagent Selection Guide

Emerging Applications: From Basic Research to Therapeutic Development

The advanced detection methods described in this guide are enabling new applications across biological research and drug discovery. In PROTAC development, ThUBD-based platforms provide robust screening systems for evaluating compound efficacy and mechanism of action [12] [13]. In neurobiology, quantitative ubiquitination analysis has revealed how aging reshapes the brain's ubiquitin landscape, with dietary restriction partially reversing some aging-related ubiquitination patterns [15]. In inflammatory disease research, chain-specific TUBEs enable precise dissection of signaling pathways, demonstrating how K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2 drives inflammatory responses [2].

The discovery that ubiquitin ligases like HUWE1 can modify drug-like small molecules themselves [7] further expands the potential applications of these detection technologies. As the ubiquitin field continues to evolve, the tools and troubleshooting approaches outlined here will remain essential for researchers tackling the fundamental challenges of dynamic modification, rapid turnover, and structural diversity in the ubiquitin system.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates nearly all cellular processes in eukaryotes, from protein degradation and DNA repair to immune signaling and cell cycle progression [6] [16] [17]. This versatile modification involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin—a small 76-amino acid protein—to substrate proteins, creating signals that can be interpreted differently based on the length and linkage type of ubiquitin chains [17] [18]. Despite its fundamental importance, the detection and characterization of ubiquitination events face significant technical challenges, primarily due to the low stoichiometry of ubiquitination under normal physiological conditions and the astounding complexity of ubiquitin chain architectures [6] [17].

These detection gaps have profound consequences for understanding disease mechanisms. Dysregulation of ubiquitination is implicated in numerous pathologies, including cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, autoimmune disorders, and muscle-wasting conditions [6] [16] [19]. When researchers cannot accurately detect and quantify ubiquitination events, they miss critical insights into how these diseases initiate and progress, hindering the development of targeted therapies. This technical support resource addresses these challenges by providing troubleshooting guidance and practical solutions for researchers struggling with ubiquitination detection in their experiments.

The Ubiquitin Code: Complexity and Consequences

The Language of Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination creates a complex "ubiquitin code" through different modification types, each capable of triggering distinct cellular outcomes [17] [18]. Understanding this code is essential for proper experimental design and interpretation.

Table 1: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Cellular Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Cellular Functions |

|---|---|

| K48-linked | Targets substrates for proteasomal degradation [16] [17] [18] |

| K63-linked | Regulates protein-protein interactions, immune signaling, and kinase activation [6] [16] [18] |

| K11-linked | Cell cycle regulation and proteasomal degradation [16] |

| K6-linked | DNA damage repair, antiviral responses [16] [18] |

| K27-linked | Controls mitochondrial autophagy [16] |

| K29-linked | Cell cycle regulation, RNA processing [16] |

| K33-linked | T-cell receptor-mediated signaling [16] |

| M1-linked (Linear) | Regulates NF-κB inflammatory signaling and cell death [16] [18] |

The complexity extends beyond simple chain linkages. Ubiquitin chains can be homotypic (single linkage type), heterotypic (mixed linkages), or branched (multiple modification sites on a single ubiquitin molecule) [6] [17]. Furthermore, ubiquitin itself can be modified by phosphorylation, acetylation, and other ubiquitin-like proteins, creating additional layers of regulation that are exceptionally difficult to detect with current methodologies [17].

Detection Challenges and Disease Understanding

The technical limitations in ubiquitination detection directly impact disease research in several critical areas:

Low Stoichiometry: Under normal physiological conditions, only a small fraction of any given substrate is ubiquitinated at a specific time, making detection difficult against the background of non-ubiquitinated proteins [6]. This is particularly problematic when studying transient signaling events or low-abundance regulatory proteins.

Dynamic and Reversible Nature: Ubiquitination is counterbalanced by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin signals, making many ubiquitination events brief and transient [16] [20]. This reversibility necessitates careful timing of experiments and use of proteasome inhibitors like MG-132 to preserve signals [20] [18].

Linkage-Specific Blindness: Many conventional detection methods, particularly antibodies, show bias toward certain linkage types (especially K48 and K63 chains) while underrepresenting atypical linkages [6] [12]. This creates an incomplete picture of the ubiquitin landscape in disease states.

Diagram 1: The ubiquitination enzymatic cascade, showing the sequential action of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes, and the reverse reaction mediated by DUBs.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Addressing Ubiquitination Detection Problems

Q1: Why do I get weak or no ubiquitination signal in my western blots, even with proteasome inhibition?

A: This common issue has multiple potential causes and solutions:

Insufficient Signal Preservation: While MG-132 and other proteasome inhibitors help, optimize concentration and treatment duration (typically 5-25 μM for 1-2 hours, but condition-specific) [20] [18]. Overexposure can cause cytotoxicity, while underexposure may not adequately preserve signals.

Improper Lysis Conditions: Use strong denaturing lysis buffers (containing SDS or urea) to inactivate DUBs and preserve ubiquitination. Avoid mild detergents that permit DUB activity during preparation [20].

Antibody Limitations: Many commercial ubiquitin antibodies have poor affinity and specificity. Validate your antibody using positive and negative controls. Consider alternatives to immunoblotting, such as TUBE-based assays or mass spectrometry [6] [18].

Q2: How can I distinguish between different ubiquitin chain linkage types in my experiments?

A: Linkage-specific detection remains challenging but several approaches exist:

Linkage-Specific Reagents: Use linkage-specific antibodies (available for K11, K48, K63, and M1 linkages) or ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) with known linkage preferences [6] [17]. Be aware that no single reagent captures all linkages equally.

Tandem Hybrid UBD (ThUBD) Technology: Recent advances like ThUBD-coated plates offer unbiased recognition of all ubiquitin chain types with high affinity, addressing the linkage bias problem [12] [13].

Mass Spectrometry: For comprehensive linkage analysis, use mass spectrometry with AQUA (absolute quantification) peptides or SILAC labeling, though this requires specialized equipment and expertise [21] [17].

Q3: My ubiquitination assays show high background noise. How can I improve specificity?

A: High background typically stems from non-specific binding or interference:

Affinity Purification Optimization: When using tagged ubiquitin (His, Strep, or FLAG), include competitive elution (imidazole for His-tag, biotin for Strep-tag) and extensive washing with buffers containing 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 or similar detergents [6] [20].

Ubiquitin Traps: Commercial tools like ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap use high-affinity nanobodies specifically engineered for ubiquitin pulldowns, offering cleaner results with lower background compared to traditional antibodies [18].

Blocking Conditions: Extend blocking time (1-2 hours) and use 5% BSA in TBST instead of milk, which can reduce non-specific antibody binding.

Advanced Detection Methodologies

Real-Time Monitoring with Fluorescence Polarization

The UbiReal assay represents a significant advancement for kinetic studies of ubiquitination. This method uses fluorescently-labeled ubiquitin to monitor all stages of ubiquitin conjugation and deconjugation in real time through fluorescence polarization (FP) measurements [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Ubiquitination Detection Methods

| Method | Key Features | Detection Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoblotting | Widely accessible, semi-quantitative | Low throughput, antibody-dependent variability, linkage bias | Initial validation, low-budget studies |

| Tagged Ubiquitin Pulldowns | Enriches low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins | Tag may alter Ub function, co-purification of non-target proteins | Proteomic screening, substrate identification |

| UbiReal (FP-based) | Real-time kinetics, monitors complete cascade | Requires fluorescent Ub, specialized equipment | Enzyme mechanism studies, inhibitor screening |

| ThUBD-coated Plates | High-throughput, minimal linkage bias | Requires specialized plates | Drug discovery, PROTAC development, quantitative profiling |

| Mass Spectrometry | Identifies modification sites, can quantify linkages | Expensive, technically complex, requires large sample input | Comprehensive ubiquitome analysis, discovery research |

Protocol: UbiReal Assay Setup

Reaction Setup: Prepare 10-20 μL reactions in black, low-volume 384-well plates. Include 50-100 nM fluorescent ubiquitin (F-Ub or T-Ub), appropriate concentrations of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM ATP) [19].

Real-Time Monitoring: Measure fluorescence polarization (FP) using a plate reader capable of FP detection (excitation 485 nm, emission 535 nm for fluorescein-labeled Ub). Take readings every 30-60 seconds to establish a kinetic profile [19].

Data Interpretation: FP increases as molecular weight increases during E1~Ub and E2~Ub thioester formation, and further during polyubiquitin chain formation. DUB activity is detected as decreasing FP signal [19].

Diagram 2: General workflow for ubiquitination detection, highlighting key challenge points where low stoichiometry can introduce artifacts.

High-Throughput Screening with ThUBD-Coated Plates

For drug discovery and PROTAC development, ThUBD-coated plates offer a robust solution for quantitative ubiquitination profiling:

Protocol: ThUBD-coated Plate Assay

Plate Preparation: Corning 3603-type 96-well plates coated with 1.03 μg ± 0.002 of ThUBD fusion protein provide optimal binding capacity for polyubiquitin chains [12].

Sample Binding: Incubate complex proteome samples (10-100 μg total protein) in binding buffer for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation. The ThUBD platform demonstrates a 16-fold wider linear range for capturing polyubiquitinated proteins compared to traditional TUBE-coated plates [12] [13].

Detection and Quantification: Wash plates thoroughly and detect captured ubiquitinated proteins using anti-ubiquitin antibodies or direct fluorescence if using labeled samples. The system enables precise quantification of ubiquitination signals across all chain types without linkage bias [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Affinity Tools | ThUBD-coated plates, TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities), Ubiquitin-Trap (ChromoTek) | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitinated proteins with minimal linkage bias; preserves ubiquitin conjugates from DUB activity [12] [18] |

| Tagged Ubiquitin | His-Ub, Strep-Ub, HA-Ub, FLAG-Ub | Purification of ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates; identification of ubiquitination sites [6] [20] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific, M1-linkage specific (linear) | Detection of specific ubiquitin chain types; understanding chain-specific signaling in disease pathways [6] [17] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG-132, Bortezomib (Velcade) | Stabilizes ubiquitinated proteins by blocking proteasomal degradation; enhances detection sensitivity [20] [18] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ub-AMC, Ub-Rhodamine, Fluorescein-Ub (F-Ub) | Monitoring DUB activity; real-time tracking of ubiquitination cascade (UbiReal assay) [19] |

The limitations in current ubiquitination detection methodologies directly impact our understanding of disease mechanisms and therapeutic development. The low stoichiometry of ubiquitination, combined with the staggering complexity of the ubiquitin code, creates significant blind spots in our knowledge of how ubiquitination pathways malfunction in disease states. However, recent technological advances—including ThUBD-based capture platforms, real-time fluorescence polarization assays, and improved mass spectrometry workflows—are gradually bridging these detection gaps.

As these methods become more accessible and widely adopted, researchers will be better equipped to decipher the complex language of ubiquitin signaling in pathological conditions. This improved detection capability will accelerate drug discovery, particularly in the rapidly growing field of targeted protein degradation (PROTACs), and provide deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms of cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, and immune disorders linked to ubiquitination pathway dysregulation.

Methodological Arsenal: Experimental and Computational Approaches for Ubiquitination Detection

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: My ubiquitin enrichment experiment shows low signal intensity. What could be the cause and how can I improve it?

A: Low signal intensity during enrichment, especially for low-stoichiometry ubiquitination, is often due to low-affinity capture reagents or inefficient binding. Traditional Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) can have limited affinity for polyubiquitinated proteins and may exhibit bias against certain ubiquitin chain types, missing critical signals [12].

- Solution: Switch to a high-affinity, unbiased capture agent. The ThUBD (Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain) reagent, for example, is engineered for high affinity and lacks linkage bias, enabling more efficient capture of polyubiquitinated proteins from complex proteomes. Ensure your detection method, such as ThUBD-coated high-density 96-well plates, is optimized for high-sensitivity detection [12].

- Protocol Adjustment: Systematically optimize your coating and washing conditions. For ThUBD-coated plates, using Corning 3603-type plates and coating with 1.03 μg of ThUBD has been shown to specifically bind approximately 5 pmol of polyubiquitin chains. Using stringent but non-denaturing wash buffers can reduce non-specific binding without eluting your target [12].

Q2: How can I generate homogeneous, site-specifically conjugated antibodies for studying ubiquitination-related pathways?

A: Achieving homogeneous multimeric conjugates is challenging with conventional methods that rely on random lysine or cysteine conjugation. The "ubi-tagging" platform addresses this by repurposing the native ubiquitination machinery for site-directed conjugation [22] [23].

- Solution: Implement the ubi-tagging technique. This method uses recombinant E1, E2, and E3 ubiquitin enzymes to covalently link a "donor" ubiquitin fusion protein (e.g., an antibody-Ub(K48R)don) to an "acceptor" ubiquitin (Ubacc-ΔGG) that is fused to your payload (e.g., a fluorescent dye or peptide) [22].

- Protocol Summary:

- Prepare Components: Generate your ubi-tagged antibody or nanobody, for example, via CRISPR/HDR genomic engineering [22] [23].

- Set Up Reaction: In a conjugation reaction, combine:

- Donor ubi-tagged protein (10 µM)

- Acceptor ubi-tagged payload (50 µM)

- E1 enzyme (0.25 µM)

- E2-E3 fusion enzyme (e.g., gp78RING-Ube2g2 for K48 linkage, 20 µM) [22].

- Incubate: Allow the reaction to proceed for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Purify: The conjugated product, such as a Rho-Ub2-Fab, can be purified using protein G or affinity chromatography [22]. This process consistently achieves conjugation efficiencies of 93-96% [23].

Q3: My immunoprecipitation for ubiquitinated proteins works with overexpressed targets but fails for endogenous proteins. How can I enhance enrichment for endogenous low-abundance targets?

A: This common issue highlights the need for enrichment strategies that preserve weak or transient interactions and are effective at native expression levels.

- Solution: Use chemically synthesized, defined ubiquitin variants as affinity matrices. Generate hydrolysis-resistant ubiquitin chains (e.g., using triazole linkages via click chemistry) to prevent cleavage by deubiquitinases (DUBs) in cell lysates. These stable chains can be immobilized on beads to enrich for specific ubiquitin-binding proteins from crude cell lysates under near-physiological conditions [24].

- Protocol Insight: For example, diubiquitin with a triazole linkage mimicking K27 chains can be synthesized using solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) to incorporate an azido-ornithine and a propargylamine, followed by a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction. This stable conjugate was key in identifying UCHL3 as a specific K27 interactor [24].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: High-Throughput Ubiquitination Detection Using ThUBD-Coated 96-Well Plates [12]

This protocol is designed for specific, rapid, and precise detection of protein ubiquitination in a high-throughput format.

Plate Coating:

- Coat Corning 3603-type 96-well plates with 1.03 μg ± 0.002 of ThUBD protein per well.

- Incubate overnight at 4°C or for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Block the plates with a suitable protein-free blocking buffer to prevent non-specific binding.

Sample Preparation and Binding:

- Prepare cell lysates using a non-denaturing lysis buffer containing protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors to preserve ubiquitination states.

- Add diluted lysate or purified ubiquitinated protein samples to the ThUBD-coated wells.

- Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking to allow binding.

Washing:

- Wash wells thoroughly with a optimized washing buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween-20) to remove unbound proteins and contaminants.

Detection:

- Add a detection reagent, such as ThUBD-HRP (Horseradish Peroxidase conjugate), and incubate.

- Develop the signal using a chemiluminescent or colorimetric substrate.

- Read the plates on a compatible microplate reader. The system can detect as little as 5 pmol of polyubiquitin chains.

Detailed Protocol: Site-Specific Antibody Conjugation via Ubi-Tagging [22]

This protocol describes how to create a fluorescently labeled Fab' fragment.

Reagent Preparation:

- Donor: Produce the Fab'-Ub(K48R)don construct. The K48R mutation prevents homodimerization.

- Acceptor: Synthesize Rho-Ubacc-ΔGG, where the C-terminal di-glycine is removed (ΔGG) to make it unreactive, and it is conjugated to a rhodamine fluorophore.

- Enzymes: Express and purify recombinant E1 and the K48-specific E2–E3 fusion enzyme gp78RING-Ube2g2.

Conjugation Reaction:

- Combine the following components in a reaction tube:

- 10 µM Fab'-Ub(K48R)don

- 50 µM Rho-Ubacc-ΔGG

- 0.25 µM E1 enzyme

- 20 µM gp78RING-Ube2g2 E2-E3 enzyme

- Incubate the reaction for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Combine the following components in a reaction tube:

Product Purification and Validation:

- Purify the conjugated product, Rho-Ub2-Fab, using protein G affinity purification.

- Validate the conjugation using SDS-PAGE (observing a single fluorescent band) and ESI-TOF mass spectrometry to confirm the expected mass and homogeneity.

Ubi-tagging Conjugation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their functions for implementing advanced affinity-based enrichment strategies.

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| ThUBD (Tandem Hybrid UBD) [12] | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitinated proteins in assays like TUF-WB or on coated plates. | Unbiased recognition of all ubiquitin chain linkage types; high sensitivity for low-stoichiometry targets. |

| ThUBD-Coated 96-Well Plates [12] | High-throughput screening and quantification of protein ubiquitination status. | Enables specific, rapid, and precise detection of ubiquitination signals from complex proteomes. |

| Ubi-Tagging Enzymes (E1, E2-E3) [22] | Site-specific, enzymatic conjugation of ubiquitin-fused payloads to antibodies/nanobodies. | Enables rapid (~30 min) generation of homogeneous conjugates with >93% efficiency. |

| Chemically Synthesized Ubiquitin Variants [24] | Serve as hydrolysis-resistant affinity baits for interactome studies (AE-MS). | Allows study of defined Ub chain types and identification of specific Ub-binding proteins. |

| PROTAC Assay Plates [12] | Commercial tool for monitoring protein ubiquitination. | Useful for initial screening, but may have limited sensitivity due to potential linkage bias of TUBEs. |

Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment Workflow

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a fundamental regulatory mechanism controlling diverse biological pathways, from protein degradation to cell signaling. However, a central challenge in the field has been the global identification and quantification of ubiquitin substrates due to the low stoichiometry of ubiquitylation, making detection of endogenously modified proteins difficult without enrichment strategies. The development of antibodies specifically recognizing the diglycine (diGly) remnant left on lysine residues after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins has revolutionized this field. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers overcome common obstacles in applying this powerful methodology to characterize the "ubiquitinome"—the array of proteins modified by the ubiquitin system.

Core Principles of diGly Remnant Capture

Fundamental Mechanisms

- diGly Remnant Generation: Trypsin cleavage of ubiquitinated proteins yields a characteristic "diGly remnant" on modified lysine residues due to cleavage of the C-terminal Arg-Gly-Gly sequence of ubiquitin [25].

- Antibody Specificity: Monoclonal antibodies specifically recognize this diGly-containing isopeptide, enabling immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitylated peptides from complex protein lysates [25] [26].

- Proteome Coverage: This approach has enabled identification of approximately 19,000 diGly-modified lysine residues within ~5,000 proteins in a single study, dramatically expanding our view of the ubiquitinome [25].

Specificity Considerations

The diGly-modified proteome represents a composite of proteins modified by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) with C-terminal diGly motifs:

- NEDD8: Contributes to diGly proteome; can be distinguished using USP2cc catalytic domain to deubiquitylate samples while preserving neddylation [25].

- ISG15: Minimal contribution in unstimulated cells (only 17 ISG15-derived diGly spectral counts detected versus >720,000 total diGly peptide counts) [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

| Problem Scenario | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low yield of ubiquitylated peptides | Inefficient enrichment; insufficient starting material; suboptimal lysis | Use denaturing lysis buffer to inhibit DUBs [25]; Ensure 3mg peptide input for enrichment [26]; Perform sequential α-diGly immunoprecipitations [25] |

| Poor reproducibility between replicates | Variable enrichment efficiency; incomplete protease inhibition | Include protease/phosphatase inhibitors in lysis buffer [27]; Standardize sample processing timing; Use consistent trypsin digestion protocols |

| Inability to distinguish ubiquitin from UBL modifications | Antibody cross-reactivity with NEDD8/ISG15 diGly remnants | Treat extracts with USP2cc to remove ubiquitin while preserving NEDD8 modifications [25]; Check ISG15 expression status (absent in unstimulated cells) [25] |

| High background in MS analysis | Non-specific antibody binding; insufficient washing | Optimize antibody:peptide ratio; Increase wash stringency; Include control IgG IP; Use peptide-based affinity enrichment [26] |

| Protein degradation during sample processing | Inadequate inhibition of proteases/DUBs | Use ice-cold conditions [27]; Add protease inhibitors immediately [27]; Process samples quickly [27]; Snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen if not processing immediately [27] |

Quantitative Data Interpretation Challenges

| Observation | Biological Interpretation | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Mixed regulation of sites within same protein | Distinct functional outcomes for individual lysines | Validate with site-directed mutagenesis; Classify sites using multi-classifier approach [25] |

| ~58% sites increase >2-fold after Btz | Accumulation of proteasome targets [25] | Compare with alternative proteasome inhibitor (e.g., epoxomycin) [25] |

| ~13% sites decrease >2-fold after Btz | Possible ubiquitin depletion effect [25] | Monitor ubiquitin pool; Assess charging of UBLs [25] |

| K11, K29, K48 linkages increase >2-fold | Proteasome-targeted linkages [25] | Compare linkage-specific antibodies; Use linkage-specific DUBs |

| K63 linkages largely unaffected | Non-proteasomal functions [25] | Assess pathway-specific activation |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Sample Preparation & Experimental Design

Q: What are the critical steps for preserving ubiquitination states during sample collection? A: Maintain samples on ice-cold conditions to slow enzymatic reactions. Use denaturing lysis buffers to immediately block deubiquitylating enzyme (DUB) activity. Incorporate protease inhibitors and consider DUB inhibitors in your lysis protocol. Process samples quickly or snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen for storage at -80°C [25] [27].

Q: How much starting material is required for comprehensive ubiquitinome analysis? A: For cell cultures, typical protocols use 1-5 million cells per condition. For tissue samples, 50-100mg provides sufficient material. From 3mg of peptides, expect approximately 5μg yield after immunoaffinity enrichment [26] [27].

Q: Can the same protocol be applied across different species or tissues? A: While the core principles remain similar, optimization may be necessary. Different species and tissues have varying protein compositions and may require tailored lysis buffers or enrichment conditions for optimal results [27].

Technical & Methodological Considerations

Q: What is the typical enrichment efficiency and selectivity for diGly peptides? A: Studies report approximately 80% enrichment selectivity, determined by the number of peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) of ubiquitylated peptides divided by total PSMs. Without enrichment, only about 0.02% of identified peptides are ubiquitylated [26].

Q: How do I validate that observed diGly sites genuinely represent ubiquitination? A: Use multiple approaches: (1) Treat samples with deubiquitylating enzymes like USP2cc prior to enrichment [25]; (2) Compare with negative controls using non-specific IgG; (3) Verify response to proteasome inhibition (e.g., bortezomib); (4) Use orthogonal methods like the IBAQ-Ub chemical proteomics approach [28] [29].

Q: What are the key considerations for quantitative studies of ubiquitination? A: For accurate quantification: (1) Use stable isotope labeling (SILAC, iTRAQ) [25] [26]; (2) Account for potential global proteome changes by parallel analysis of ubiquitinome and global proteome [26]; (3) Consider using the IBAQ-Ub method for stoichiometric analysis [28] [29]; (4) Perform multiple biological replicates to account for identification variability between runs [25].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: diGly Remnant Enrichment for Ubiquitinome Analysis

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in denaturing buffer (e.g., 8M urea, 50mM Tris-HCl, pH8.0) containing protease inhibitors and DUB inhibitors to preserve ubiquitination states [25].

- Protein Digestion: Reduce, alkylate, and digest proteins with trypsin (1:50 w/w ratio) at 37°C overnight [25] [26].

- diGly Peptide Enrichment: Incubate tryptic peptides with anti-diGly antibody conjugated to beads for 2-4 hours at 4°C. Perform 3-4 sequential immunoprecipitations to maximize yield [25].

- Wash and Elution: Wash beads extensively with ice-cold IP buffer, then elute diGly peptides with 0.1% TFA or low-pH buffer [25].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Desalt peptides and analyze by LC-MS/MS using high-resolution mass spectrometry [25] [26].

Protocol 2: Specificity Control Using USP2cc Treatment

- Prepare Cell Lysates: Lyse cells in non-denaturing buffer supplemented with DUB inhibitors.

- USP2cc Treatment: Incubate lysates with catalytic domain of USP2 (1μg/100μg protein) for 1-2 hours at 37°C [25].

- Terminate Reaction: Add denaturing buffer and heat at 95°C for 10 minutes.

- Process Samples: Continue with standard protein digestion and diGly enrichment protocol.

- Data Analysis: Compare USP2cc-treated samples with untreated controls; genuine ubiquitin signals should decrease by ≥50% while NEDD8 modifications remain [25].

Quantitative Data Interpretation Framework

Response to Proteasome Inhibition

Proteasome inhibition with bortezomib (1μM for 8 hours) reveals distinct classes of ubiquitination dynamics [25]:

Linkage-Specific Dynamics After Proteasome Inhibition

Quantitative diGly proteomics reveals distinct fates for different ubiquitin linkage types following proteasome inhibition [25]:

| Ubiquitin Linkage | Response to Proteasome Inhibition | Functional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| K48 linkages | Increase >2-fold | Primary proteasomal targeting signal |

| K11 linkages | Increase >2-fold | Proteasomal degradation |

| K29 linkages | Increase >2-fold | Proteasomal degradation |

| K63 linkages | Largely unaffected | Non-proteasomal functions (signaling, DNA repair) |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for successful diGly remnant capture experiments:

| Reagent | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| diGly Remnant Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitylated peptides | Cell Signaling Technology #5562; Various monoclonal antibodies [25] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent protein degradation during sample preparation | Complete Mini EDTA-free (Roche); PMSF; Various protease inhibitor cocktails [27] |

| Deubiquitylating Enzyme Inhibitors | Preserve ubiquitination states | N-ethylmaleimide; PR-619; Ubiquitin Aldehyde |

| USP2 Catalytic Domain | Specific removal of ubiquitin while preserving NEDD8 | Recombinant USP2cc (used to distinguish ubiquitin from NEDD8 modifications) [25] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Validate ubiquitination accumulation | Bortezomib; Epoxomycin; MG132 [25] |

| Stable Isotope Labels | Quantitative proteomics | SILAC (K8; Lys+8Da); iTRAQ reagents; TMT labels [25] [26] |

| Mass Spec Standards | System performance validation | Pierce HeLa Protein Digest Standard (Cat. No. 88328) [30] |

| Retention Time Calibrants | LC system troubleshooting | Pierce Peptide Retention Time Calibration Mixture (Cat. No. 88321) [30] |

Advanced Methodologies

IBAQ-Ub for Stoichiometric Analysis

The Isotopically Balanced Quantification of Ubiquitination (IBAQ-Ub) approach enables site-specific stoichiometry analysis:

- Utilizes an amine-reactive chemical tag (AcGG-NHS) structurally homologous to the GG remnant [28] [29].

- Generates structurally identical peptides from ubiquitinated and unmodified lysine residues after trypsin digestion [28] [29].

- Enables absolute quantification of fractional abundance of ubiquitination [28] [29].

Integrated Global and Ubiquitylated Proteome Analysis

For comprehensive understanding:

- Analyze both ubiquitin-modified proteome and cognate global proteome from the same samples [26].

- Use isobaric tags (iTRAQ, TMT) for multiplexed relative quantification [26].

- Identify proteins with specific changes in ubiquitylation independent of global protein level changes [26].

This technical support resource will continue to evolve as new methodologies and troubleshooting insights emerge in the rapidly advancing field of ubiquitinomics.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Low or No Ubiquitination Signal

Q: My high-throughput assay shows a weak or absent ubiquitination signal, even though my protein of interest is expressed. What could be wrong?

A: This is a common challenge when detecting low-stoichiometry ubiquitination events. The issue often lies with the ubiquitin-binding tool's affinity or the lysis conditions.

- Possible Cause: Low-Affinity Capture Reagent. Traditional tools like TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) may have insufficient affinity or exhibit linkage bias, failing to capture ubiquitinated proteins present at low abundances [13].

- Solution: Implement a high-affinity, linkage-independent capture platform. ThUBD (Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain)-coated plates demonstrate a 16-fold wider linear range for capturing polyubiquitinated proteins compared to TUBE-coated plates, significantly enhancing sensitivity for detecting low-stoichiometry events [13] [31].

- Possible Cause: Denaturing Lysis Conditions. The use of stringent lysis buffers, such as RIPA buffer (which contains ionic detergents like sodium deoxycholate), can disrupt protein-protein interactions and denature enzymes, thereby preventing ubiquitination during the assay [32].

- Solution: Use a milder, non-denaturing cell lysis buffer (e.g., Cell Lysis Buffer #9803) for immunoprecipitation and co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Ensure sonication is performed to adequately shear DNA and recover proteins without disrupting complexes [32].

High Background or Non-Specific Signal

Q: I am getting multiple non-specific bands or high background in my detection. How can I improve the specificity?

A: High background is frequently caused by non-specific binding to solid supports or antibody cross-reactivity.

- Possible Cause: Non-Specific Binding to Beads. Proteins can bind non-specifically to the Protein A or G beads themselves, or to the IgG of the antibody used for pulldown [32].

- Solution:

- Include a bead-only control (beads incubated with lysate without a specific antibody) to identify proteins that bind non-specifically to the beads. If this control shows background, pre-clear your lysate by incubating it with beads alone before the IP [32].

- Include an isotype control (an antibody of the same species and isotype but without specificity for your target) to distinguish background caused by non-specific IgG binding [32].

- Possible Cause: Detection of Antibody Heavy and Light Chains. When the primary antibody used for the western blot is from the same species as the IP antibody, the secondary antibody will detect the denatured IgG chains (~25 kDa and ~50 kDa), which can obscure your target signal [32].

- Solution:

- Use antibodies from different host species for the IP and the western blot (e.g., rabbit for IP, mouse for western blot) [32].

- Use a biotinylated primary antibody for western blotting, followed by detection with Streptavidin-HRP [32].

- Use a light-chain specific secondary antibody for western blotting if your target protein does not migrate near 25 kDa [32].

Distinguishing Ubiquitination Types

Q: How can I determine if my protein is modified by polyubiquitin chains or multiple mono-ubiquitination events?

A: This requires a method that can differentiate between these two types of modifications.

- Solution: A key method is a DTT-sensitive thio-ester assay. In this assay, E2~Ub thio-ester intermediates are sensitive to DTT (or β-mercaptoethanol) treatment, which cleaves the bond, causing a mobility shift on a western blot. In contrast, isopeptide bonds formed in polyubiquitination or multi-mono-ubiquitination are stable in the presence of DTT [33]. By running samples with and without DTT in the SDS sample buffer, you can distinguish between these linkages. The protocol involves incubating E1, E2, and ubiquitin, then splitting the reaction into +/- DTT samples before SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis [33].

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Cascades

Protocol 1: DTT-Sensitive Thio-Ester Assay for E2~Ub Intermediate

This protocol tests the activity of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) by detecting the formation of a thio-ester linkage with ubiquitin [33].

Detailed Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: In a total volume of 30 µL, combine:

- 1.5 µL of 20x Reaction Buffer

- 50 ng of E1 enzyme

- 200-500 ng of recombinant E2 enzyme

- 2 µg of Ubiquitin

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 5 minutes.

- Sample Splitting: Split the reaction into two equal parts. Add 10 µL of 4x SDS sample buffer with DTT to one tube and 10 µL of 4x SDS sample buffer without DTT to the other.

- Denaturation: Boil both samples at 100°C for 5 minutes.

- Detection: Resolve the products on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. Perform western blotting using an anti-ubiquitin antibody or an antibody against the tag fused to the E2 protein (e.g., anti-His). The DTT-sensitive thio-ester linkage will be present in the "-DTT" lane and disappear in the "+DTT" lane [33].

Protocol 2: In Vitro E3 Autoubiquitination Assay

This protocol assesses the E3 ligase activity of a protein of interest [33].

Detailed Methodology:

- Immobilize E3 Ligase: If using a tagged E3 (e.g., MBP-E3), immobilize 0.5-1 µg of the protein from a crude extract onto amylose resin beads. Wash the beads thoroughly with an appropriate buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5).

- Reaction Setup: To the beads containing the immobilized E3, add a 30 µL reaction mixture containing:

- 1.5 µL of 20x Reaction Buffer

- 50 ng of E1 enzyme

- 200-500 ng of E2 enzyme

- 5 µg of Ubiquitin

- Control Reactions: Set up control reactions minus E1 and minus E2.

- Incubation: Incubate the reactions at 30°C for 1.5 hours with constant agitation (e.g., 900 rpm in a thermomixer).

- Detection: Add 10 µL of 4x SDS sample buffer (with DTT), boil, and run on an 8-12% SDS-PAGE gel. Detect the ubiquitinated E3 by western blot using an anti-ubiquitin antibody or an antibody against the tag fused to the ubiquitin or E3 protein [33].

Protocol 3: High-Throughput Ubiquitination Profiling with ThUBD-Coated Plates

This protocol leverages a novel technology for the sensitive, high-throughput detection of ubiquitination signals from complex samples, directly addressing low stoichiometry challenges [13] [31].

Detailed Methodology:

- Plate Preparation: Use 96-well plates pre-coated with the high-affinity Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain (ThUBD).

- Sample Application: Apply complex proteome samples (from cells, tissues, or other biological sources) to the wells. The ThUBD domain will unbiasedly capture proteins modified with all types of ubiquitin chains.

- Incubation and Washing: Incubate to allow binding, then wash the plates to remove non-specifically bound material.

- Detection and Quantification: Detect the captured ubiquitinated proteins using specific antibodies (for target-specific analysis) or general ubiquitin detection reagents (for global profiling). The high affinity of ThUBD allows for precise quantification of the ubiquitination signal [13] [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents for studying ubiquitination cascades.

| Reagent/Kit | Function/Brief Explanation | Key Feature / Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ThUBD-Coated Plates [13] [31] | High-throughput, sensitive capture of ubiquitinated proteins. | Unbiased, high-affinity binding to all ubiquitin chain linkages; 16x wider linear range than TUBEs. Ideal for global profiling and low-stoichiometry detection. |

| TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) [13] | Capture and enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins. | Affinity-based tool; can exhibit linkage bias and lower affinity compared to ThUBD. |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies [33] | Detection of ubiquitinated proteins via western blot. | Crucial for visualizing ubiquitination in assays like E2 thio-ester and E3 autoubiquitination. |

| Tag-Specific Antibodies (e.g., Anti-His, Anti-MBP) [33] | Detection of recombinant, tagged proteins (E1, E2, E3, Ub) in assays. | Enables specific monitoring of individual components in the ubiquitination cascade. |

| Nickel-HRP [33] | Direct detection of His-tagged proteins on western blots. | Useful for detecting His-tagged ubiquitin in in vitro assays without a primary antibody. |

| Mild Cell Lysis Buffer [32] | Extraction of proteins under non-denaturing conditions. | Preserves protein-protein interactions and enzymatic activities for functional ubiquitination assays. |

| Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails [32] | Prevent protein degradation and maintain post-translational modifications during lysis. | Essential for preserving the native ubiquitination state of proteins. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Visualizing the Workflow

Ubiquitination Cascade Pathway

High-Throughput Detection Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use computational predictors for ubiquitination sites instead of traditional experimental methods?

Experimental techniques like mass spectrometry (MS) for identifying ubiquitination sites (Ubi-sites) can be costly, time-consuming, and challenging, particularly for low-stoichiometry ubiquitination events that are transient or rare. Computational tools leverage artificial intelligence to analyze protein sequences and predict potential Ubi-sites rapidly and cost-effectively, helping to prioritize targets for wet-lab validation and offering insights into regulatory mechanisms [34].

Q2: What is the typical input data format required by these prediction tools?

Most tools, such as UbPred, require a protein sequence in FastA format as input. The sequence should ideally be 25 or more residues long and must contain at least one lysine (K) residue, as ubiquitination occurs at lysine side chains [35].

Q3: I need to run predictions on multiple sequences. Why am I limited to one sequence at a time with some web servers?

Some servers, like UbPred, perform evolutionary feature extraction by running PSI-BLAST to create Position-Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSMs). This process is computationally intensive and can take up to 45 minutes per sequence. To manage server load and prevent excessive wait times for all users, these services often limit the number of concurrent requests per user [35].

Q4: What do the confidence scores (e.g., Low, Medium, High) in the prediction output mean?

Confidence scores are based on the predictor's output score and correspond to different levels of estimated sensitivity and specificity. For example, UbPred uses the following ranges [35]:

| Confidence Label | Score Range | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.62 – 0.69 | 0.464 | 0.903 |

| Medium | 0.69 – 0.84 | 0.346 | 0.950 |

| High | 0.84 – 1.00 | 0.197 | 0.989 |

A "High" confidence prediction has very high specificity (low chance of being a false positive) but lower sensitivity, meaning it will identify fewer true positives.

Q5: Which tool is better for my research, UbPred or a newer tool like Ubigo-X?

The choice depends on your specific needs. UbPred is a well-established random forest-based predictor that was primarily trained on data from S. cerevisiae (yeast) and uses sequence and evolutionary features [36]. Ubigo-X is a more recent, species-neutral deep learning model that integrates multiple feature types, including k-mer sequences and structural features, and has demonstrated strong performance on balanced and imbalanced human data [37]. For human proteome studies, especially with large datasets, newer deep learning models may offer advantages.

Q6: What are the key performance metrics for comparing different Ubi-site prediction tools?

Key metrics to compare tools include [37] [34]:

- AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve): Measures the overall ability to distinguish between positive and negative sites. Closer to 1.0 is better.

- Accuracy (ACC): The proportion of total correct predictions.

- Precision: The proportion of predicted positive sites that are correct.

- Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of actual positive sites that are correctly identified.

- MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient): A more reliable metric for imbalanced datasets, with a range of -1 to +1.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Long Wait Times for Online Prediction Results

Problem: Submission of a protein sequence to a web server (e.g., UbPred) results in a notification of a long processing time, or results are delivered via email after a significant delay.

Explanation: This occurs when the server needs to generate a new PSSM profile for your sequence using PSI-BLAST, which is a computationally expensive process. The delay is due to the queue of jobs from other users [35].

Solution:

- Be Patient: The server may take up to 45 minutes for a single sequence.

- Use a Standalone Version: If available, download and install the standalone version of the tool (e.g., UbPred offers Linux and Windows versions) to run predictions locally on your own hardware without queue delays [35].

- Explore Alternative Tools: Consider using other predictors that may have different computational backends or faster processing times for high-throughput analysis.

Issue: Handling Class Imbalance in Custom Model Training