Overcoming Weak Immunogenicity in Ubiquitin Antibodies: Advanced Strategies for Research and Therapeutic Development

This article addresses the significant challenge of weak immunogenicity in ubiquitin antibodies, a major bottleneck in proteomics and therapeutic development.

Overcoming Weak Immunogenicity in Ubiquitin Antibodies: Advanced Strategies for Research and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article addresses the significant challenge of weak immunogenicity in ubiquitin antibodies, a major bottleneck in proteomics and therapeutic development. We explore the foundational reasons behind this poor immune recognition, from structural constraints to detection failures. The content provides a comprehensive guide to advanced methodological solutions, including innovative antigen design and site-specific conjugation techniques. It further covers critical troubleshooting for purification and assay optimization, and concludes with robust validation frameworks to ensure antibody specificity and functionality. This resource is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to generate high-quality ubiquitin reagents for basic research, diagnostic, and clinical applications.

Ubiquitin Immunogenicity: Unraveling the Core Challenges and Biological Complexities

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Core Concepts

Q1: What makes ubiquitin a "poor immunogen"? Ubiquitin is considered a poor immunogen due to a combination of its small size, high structural conservation across evolution, and intrinsic biochemical properties. Its 76-amino-acid length is close to the lower molecular weight threshold for effective immune recognition [1] [2]. Furthermore, it is one of the most evolutionarily conserved eukaryotic proteins; for instance, plant ubiquitin differs from human ubiquitin by only three amino acids [1]. This high degree of conservation means the immune system often recognizes it as "self," leading to immune tolerance and a weak antibody response.

Q2: If ubiquitin is so conserved, how can we ever generate antibodies against it? While challenging, generating antibodies is possible by targeting unique aspects of the ubiquitin signal. Successful strategies often focus on specific epitopes that are not conserved or on the isopeptide bond itself. These include:

- Site-specific ubiquitination: Creating antibodies that recognize ubiquitin attached to a specific lysine residue on a particular protein (e.g., H2B-K123ub) [2].

- Linkage-specific chains: Generating antibodies that distinguish between different polyubiquitin chain linkages (e.g., K48 vs. K63 chains) [3].

- Stable antigen mimics: Using synthetic, non-hydrolyzable ubiquitin-peptide conjugates as immunogens to overcome the rapid cleavage of native ubiquitin by deubiquitinases (DUBs) in vivo [2].

Q3: What is the "ubiquitin code" and why is it relevant to antibody generation? The "ubiquitin code" refers to the vast diversity of signals created when ubiquitin modifies proteins. Ubiquitin can be attached as a single molecule (monoubiquitination) or in chains (polyubiquitination) using any of its seven internal lysine residues or its N-terminal methionine [1] [4]. Each linkage type can represent a distinct cellular signal. For example, K48-linked chains typically target proteins for degradation, while K63-linked chains are involved in immune signaling and DNA repair [3]. This complexity means a single, generic anti-ubiquitin antibody is insufficient to study specific pathways, creating a pressing need for a toolkit of highly specific antibodies to decipher this code.

Technical Challenges

Q4: What are the main technical hurdles in producing a site-specific ubiquitin antibody? Generating site-specific ubiquitin antibodies faces several key technical hurdles, summarized in the table below.

Table: Key Technical Hurdles in Site-Specific Ubiquitin Antibody Generation

| Hurdle | Description |

|---|---|

| Large, Hydrolyzable Epitope | The epitope includes both part of the target protein and the ubiquitin molecule, linked by a native isopeptide bond that is rapidly cleaved by deubiquitinases (DUBs) during immunization [2]. |

| Complex Antigen Synthesis | Incorporating a 76-amino-acid ubiquitin modification into a peptide antigen requires advanced chemical synthesis methods, unlike simpler modifications like phosphorylation [2] [5]. |

| Weak Immunogenicity | The small size and high conservation of ubiquitin result in a weak immune response, making it difficult to elicit high-affinity antibodies [3]. |

Q5: Why are standard antibody generation protocols insufficient for ubiquitin? Standard protocols often rely on short, modified peptides for immunization. For ubiquitin, this is inadequate because:

- Short peptides cannot recapitulate the conformational epitope formed by the ubiquitin-protein complex.

- The native isopeptide bond is lysed by deubiquitinases present in the serum of immunized animals, destroying the antigen before a robust immune response can be mounted [2]. Therefore, specialized protocols using full-length ubiquitin and stable, non-hydrolyzable bond mimics are required.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Detection of Ubiquitinated Proteins by Western Blot

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table: Troubleshooting Inconsistent Ubiquitin Detection

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background or smeared signal | Non-specific antibody binding or heterogeneous ubiquitinated proteins. | Use linkage-specific antibodies to resolve discrete bands. Pre-clear lysate with protein A/G beads. Optimize antibody dilution and blocking conditions [3]. |

| Weak or no signal | Low abundance of specific ubiquitination event; antibody not specific for the modification. | Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) to enrich for ubiquitinated proteins prior to lysis [3]. Validate antibody using a known positive control. |

| Signal disappears rapidly | Sample degradation by active deubiquitinases (DUBs) during preparation. | Include DUB inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide) in the lysis buffer. Keep samples on ice and process quickly [5]. |

Problem: Failure to Generate a High-Affinity, Site-Specific Antibody

Recommended Workflow and Strategy: This guide outlines a proven strategy for developing site-specific ubiquitin antibodies, based on a successful effort to generate an antibody against ubiquitinated histone H2B (H2B-K123ub) [2].

1. Antigen Design and Synthesis:

- For Immunization: Synthesize a non-hydrolyzable ubiquitin-peptide conjugate. The native isopeptide bond is replaced with a stable amide triazole isostere, which mimics the native bond's structure but resists cleavage by DUBs [2].

- For Screening: Synthesize an extended native isopeptide-linked ubiquitin-peptide conjugate for hybridoma screening. This ensures selected clones recognize the true, native epitope.

2. Immunization and Hybridoma Generation:

- Follow standard protocols for mouse immunization and hybridoma generation.

- Screen hybridoma supernatants using the native isopeptide-linked antigen from step 1.

3. Clone Selection and Validation:

- Select clones that show strong specificity for the native epitope.

- Validate rigorously: Test antibody performance in the intended applications (e.g., immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, chromatin immunoprecipitation) using both wild-type and ubiquitin-site-mutant cell lines as controls [2].

Diagram: Workflow for Generating Site-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies. This flowchart outlines the key steps, highlighting the critical stage of creating a stable antigen.

Problem: Differentiating Between Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Types

Solution: Employ a combination of specific reagents and experimental techniques.

- Use Linkage-Specific Antibodies: A growing number of commercial antibodies are specific for K48, K63, M1, and other linkage types. Always validate them in your specific experimental system [3].

- Utilize Linkage-Specific DUBs: Express or purify DUBs that are specific for certain chain types (e.g., OTULIN for M1-linked chains) to enzymatically disassemble specific chains as a control [4].

- Employ Ubiquitin Traps: Use tools like the ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap (a nanobody-based reagent) to enrich for all ubiquitinated proteins, then probe the precipitate with linkage-specific antibodies to determine the types of chains present [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential reagents for overcoming hurdles in ubiquitin research, particularly for detection and conjugation applications.

Table: Essential Reagents for Advanced Ubiquitin Research

| Reagent | Function & Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Nanobody) | Immunoprecipitation of mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins from cell extracts [3]. | Binds a wide range of ubiquitin linkages; useful for IP-MS workflows. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detects specific polyubiquitin chain types (e.g., K48, K63) in Western blot or IF [3]. | Essential for deciphering the functional "ubiquitin code." |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) | Enriches ubiquitinated proteins in cells by blocking their degradation [3]. | Critical for enhancing detection signal of labile ubiquitination events. |

| Engineered Ubiquitin (e.g., K48R, ΔGG) | Used in novel conjugation techniques like "ubi-tagging" to create defined antibody conjugates [6]. | Allows precise, site-directed multimerization of proteins and payloads. |

| Recombinant E1, E2, E3 Enzymes | For in vitro ubiquitination assays or enzymatic conjugation strategies [6] [5]. | Provides control over ubiquitin linkage type in synthetic biology applications. |

Visualizing Ubiquitin's Structural Challenge

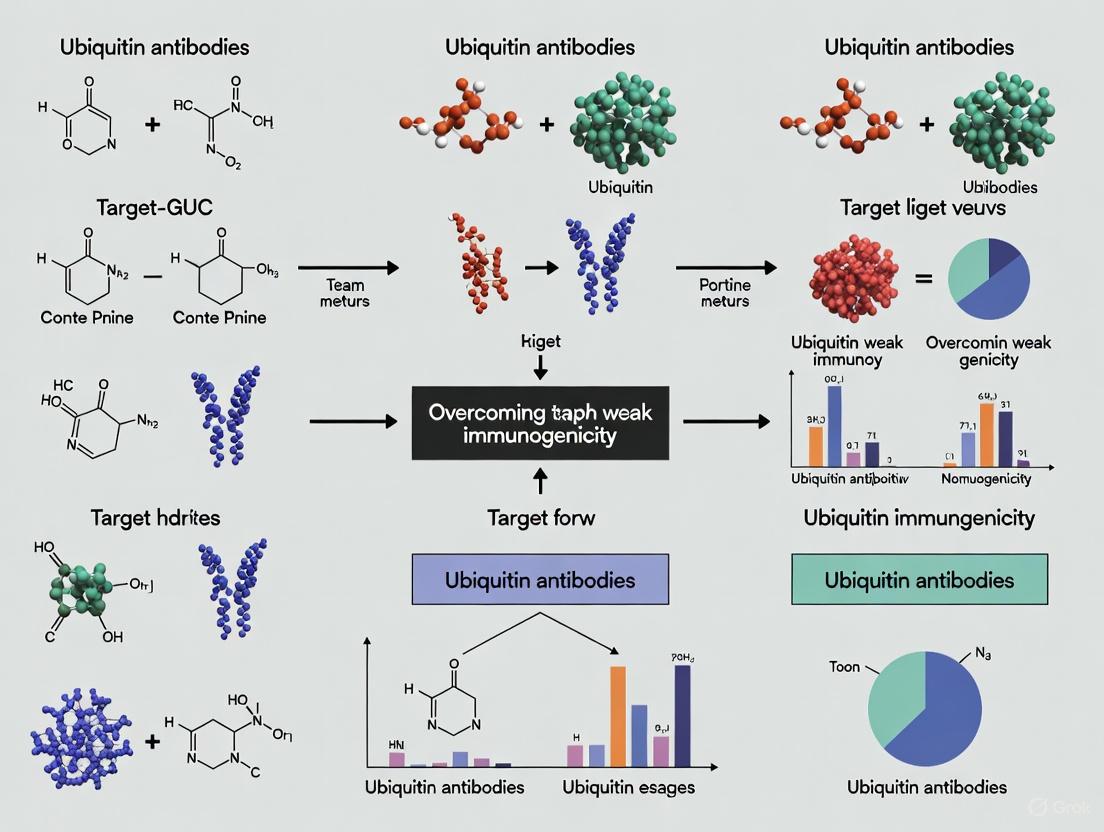

The diagram below illustrates the core structural and evolutionary reasons why ubiquitin is a poor immunogen, and the primary strategies used to overcome this challenge.

Diagram: Structural and Evolutionary Hurdles of Ubiquitin. The diagram contrasts ubiquitin's inherent properties that make it a poor immunogen (top) with the key strategies researchers use to overcome these hurdles (bottom).

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Ubiquitin Antibody-Based Experiments

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when working with ubiquitin antibodies, focusing on overcoming weak immunogenicity and detecting diverse ubiquitin signaling forms.

Q1: My Western blot shows no signal for ubiquitinated proteins. What could be wrong?

- Confirm Protein Transfer: Use Ponceau S staining to verify successful transfer of proteins from the gel to the membrane. Small proteins may pass through the membrane, while large ones may not transfer effectively; optimize transfer time accordingly [7].

- Check Antibody Specificity: Ensure your primary antibody is validated for Western blot and recognizes the specific ubiquitin chain linkage or type (e.g., K48, K63, mono-ubiquitin) you are investigating. Run a positive control lysate known to contain ubiquitinated proteins [7] [8].

- Optimize Antibody Concentration: The antibody concentration may be too low. Titrate both primary and secondary antibodies. Consider incubating with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C to enhance binding [7].

- Verify Antigen Presence: Ensure sufficient target protein is present in your sample. Use a total protein assay and consider enriching your protein of interest via immunoprecipitation before blotting, especially if it is low-abundance [7].

- Check Reporter System: Ensure your ECL reagents are fresh and active. Confirm that wash buffers and antibody diluents are free of sodium azide, which inhibits peroxidase activity [7].

Q2: I am getting high background noise on my Western blot, obscuring specific bands.

- Optimize Blocking: Use an effective blocking agent like 5% non-fat dry milk or 3% BSA. However, if using a primary antibody raised in goat or sheep, avoid milk or BSA in your diluent and use 5% normal serum from the host species of the secondary antibody instead [7].

- Titrate Antibodies: High background often results from excessive antibody concentration. Dilute your primary and/or secondary antibodies further [7].

- Increase Washing Stringency: After antibody incubation, wash the membrane thoroughly with a buffer containing a detergent such as 0.05% Tween-20, ensuring sufficient volume, time, and number of washes [7].

- Reduce Sample Load: Overloading the gel with too much total protein (e.g., >10 µg per lane) can cause high background. Reduce the load or use immunoprecipitation to enrich your target [7].

Q3: I see multiple unexpected bands on my blot. How can I confirm specificity?

- Identify Non-Specific Binding: Run a negative control (e.g., a cell lysate where the target protein is knocked out or not expressed) to identify bands caused by non-specific binding of the primary antibody [7].

- Prevent Protein Degradation: Multiple lower molecular weight bands may indicate protein degradation. Add fresh protease inhibitors to your lysis buffer and handle samples on ice [7].

- Account for Post-Translational Modifications: Heterogeneity from modifications like phosphorylation or glycosylation can cause smearing or multiple bands. Treatments with specific enzymes (e.g., phosphatases, glycosylases) can help confirm this [7].

- Run a Secondary-Only Control: Incubate the blot with the secondary antibody alone to rule out non-specific binding from the detection system [7].

Q4: How can I specifically detect different types of ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48 vs. K63)?

- Use Linkage-Specific Antibodies: Invest in antibodies specifically validated to recognize K48-linked, K63-linked, or other specific ubiquitin chain topologies. These are crucial for studying non-degradative ubiquitin signaling [9] [8].

- Employ Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs): Utilize TUBEs in your immunoprecipitation protocol. These engineered molecules have high affinity for polyubiquitin and can protect ubiquitinated proteins from deubiquitinases (DUBs) during sample preparation, enriching for specific chain types [9].

- Combine with Mass Spectrometry: For definitive identification of ubiquitin chain linkage, follow immunoprecipitation with mass spectrometry analysis, which can map the specific lysine residues involved in the ubiquitin chain [10].

Q5: My immunoprecipitation (IP) of ubiquitinated proteins is inefficient, possibly due to weak antibody immunogenicity. What can I do?

- Use Cross-Reactive TUBEs: If antibodies are ineffective, TUBEs offer a robust alternative for pulldown experiments as they are not antibodies and are not subject to immunogenicity issues [9].

- Optimize IP Conditions: Ensure you are using the correct buffer conditions (e.g., lysis buffer with protease and DUB inhibitors). The amount of IP antibody may be insufficient; increase the concentration, but do not exceed 10-20 µg per lane to avoid overloading and background issues [7].

- Confirm Antibody Binding Capacity: Verify that your antibody is capable of recognizing ubiquitinated proteins in their native or denatured state, depending on your IP protocol. Check manufacturer datasheets for validation in IP applications [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitin Research

| Reagent Type | Key Examples | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Anti-K48, Anti-K63, Anti-linear ubiquitin [9] | Detect specific polyubiquitin chain topologies in techniques like Western blot, IF, and IP to distinguish between degradative and non-degradative signaling. |

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Inhibitors | Hakai HYB domain-targeting inhibitor [10], JNJ-165, MLN4924 [9] | Selectively inhibit the activity of specific E3 ligases to study their function in pathways like EMT or NF-κB signaling. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | b-AP15 [9] | Inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes, stabilizing ubiquitin signals on target proteins and allowing for better detection. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib [9] | Block the proteasome, preventing the degradation of K48-linked polyubiquitinated proteins and enabling their accumulation for study. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Recombinant TUBEs [9] | High-affinity tools for pulldown of ubiquitinated proteins from lysates, offering protection from DUBs and an alternative to immunoprecipitation with antibodies. |

| Ubiquitin Activation (E1) Inhibitors | PYR-41 [9] | Block the initial step of the ubiquitination cascade, inhibiting all cellular ubiquitination. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Investigating Hakai-Mediated E-Cadherin Regulation

This protocol outlines a methodology to study the ubiquitination of E-cadherin by the E3 ligase Hakai, a key process in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [10].

1. Cell Stimulation and Lysis

- Culture appropriate epithelial cells (e.g., MCF-10A or MDCK).

- To induce E-cadherin phosphorylation and Hakai binding, treat cells with a Src family kinase activator (e.g., pervanadate) or a cytokine like TGF-β1 (which can upregulate Hakai expression) for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-120 minutes) [10].

- Place cells on ice, wash with cold PBS, and lyse using a RIPA buffer supplemented with:

- Protease inhibitor cocktail

- Phosphatase inhibitors (e.g., sodium orthovanadate)

- Deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide) to preserve ubiquitin signals

- � Proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132 at 10 µM) to prevent degradation of ubiquitinated E-cadherin.

- Centrifuge lysates at 14,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C and collect the supernatant.

2. Immunoprecipitation of E-cadherin

- Pre-clear the cell lysate with Protein A/G beads for 30 minutes at 4°C.

- Incubate the pre-cleared lysate with an anti-E-cadherin antibody conjugated to beads (or add antibody first, then beads) overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- The following diagram illustrates the core molecular interplay investigated in this protocol:

3. Western Blot Analysis

- Wash the immunoprecipitation beads thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elute the bound proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer.

- Separate the proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane.

- Block the membrane with 5% BSA in TBST for 1 hour.

- Probe the membrane with the following antibodies:

- Primary Antibodies:

- Mouse anti-Ubiquitin (or linkage-specific ubiquitin antibody to determine chain type) to detect ubiquitinated E-cadherin.

- Rabbit anti-E-cadherin to confirm successful IP and total E-cadherin levels.

- Rabbit anti-Hakai to check for co-immunoprecipitation with E-cadherin.

- Secondary Antibodies:

- Use species-appropriate secondary antibodies (e.g., anti-mouse for ubiquitin, anti-rabbit for E-cadherin/Hakai) conjugated to HRP or a fluorescent dye.

- Primary Antibodies:

- Develop the blot using ECL or your preferred detection system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the key non-degradative roles of ubiquitin signaling I should investigate? A: Beyond targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation via K48-linked chains, ubiquitination is critically involved in:

- DNA Repair & Immune Signaling: K63-linked chains are pivotal in the DNA damage response and in activating key immune pathways like NF-κB [9].

- mRNA Metabolism & Cancer: Hakai, an E3 ligase, has a non-canonical role as part of the m6A methyltransferase complex that modifies RNA, influencing mRNA fate and contributing to cancer progression [10].

- Inflammation Regulation: Linear ubiquitin chains, assembled by the LUBAC complex, are essential for full activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways in response to inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, which is implicated in autoimmune diseases like APS [9].

Q: My ubiquitin antibody works in Western blot but not for Immunofluorescence (IF). What are potential reasons? A: This is common and often related to epitope accessibility.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: The ubiquitin epitope may be masked by your fixation method (e.g., over-fixation with formaldehyde). Try different permeabilization conditions (e.g., using detergents like Triton X-100 or saponin) or antigen retrieval methods to expose the epitope [11].

- Antibody Validation: Not all antibodies are validated for IF. Check the manufacturer's datasheet for validated applications. The antibody may only recognize denatured ubiquitin (as in Western blots) but not the native protein in IF.

- Signal-to-Noise: The ubiquitin signal might be diffuse and weak. Use a positive control (e.g., cells treated with a proteasome inhibitor to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins) and a high-quality, fluorescently labeled secondary antibody to enhance signal.

Q: How can I study the role of a specific E3 ligase, like Hakai, in a signaling pathway? A: A multi-pronged approach is most effective:

- Genetic Manipulation: Use siRNA, shRNA, or CRISPR/Cas9 to knock down or knock out the CBLL1 gene (encoding Hakai) in your cell model and observe the phenotypic and molecular consequences [10].

- Pharmacological Inhibition: If available, use a specific small-molecule inhibitor. For instance, the first Hakai inhibitor targeting its unique HYB domain has been developed and shows promise in disrupting its function [10].

- Proximity Ligation Assays (PLA): Use PLA to visualize and quantify the direct interaction between Hakai and its substrate (like E-cadherin) in situ within cells, which can provide spatial information about the interaction.

FAQs: Understanding the Core Challenges in HCP and Immunogenicity Detection

Q1: What is the primary "blind spot" of ELISA in Host Cell Protein (HCP) detection? The fundamental blind spot of ELISA is its reliance on polyclonal antibody (pAb) reagents generated against a complex mixture of HCPs. This approach is inherently limited by the coverage and quality of these antibodies. If an HCP is poorly immunogenic or under-represented in the immunogen mixture, the pAbs may fail to generate a strong immune response, leading to antibodies that cannot detect that specific HCP in an assay. This creates a detection gap, where harmful HCPs can remain undetected in the final drug substance, posing a potential safety risk to patients [12].

Q2: How can mass spectrometry address the limitations of ELISA for HCP analysis? Mass spectrometry (MS) serves as a powerful orthogonal method that does not rely on immunoreagents. It directly identifies and quantifies individual HCP species in a sample. MS is particularly valuable for:

- Identifying specific HCPs: It can detect low-abundance HCPs that might be missed by ELISA.

- Process optimization: It helps understand how upstream and downstream processes influence the HCP profile.

- Evaluating ELISA coverage: Techniques like immunoaffinity chromatography-MS (IAC-MS) can identify which HCPs are not captured by the ELISA's pAbs, allowing for risk assessment and kit improvement [12].

Q3: Why is immunogenicity a concern for therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), and how can it be mitigated? Immunogenicity refers to the unwanted immune response against a therapeutic drug, leading to the production of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs). ADAs can reduce drug efficacy, increase clearance, and cause adverse immune reactions. Mitigation strategies include:

- Humanization: Replacing non-human components of the antibody (e.g., from murine sources) with human sequences to reduce recognition as "foreign" [13].

- Sequence Optimization: Using computational tools to minimize T-cell epitopes that can drive an immune response [14].

- Comprehensive Risk Assessment: Employing a combination of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo strategies to evaluate immunogenicity risk early in drug development [13].

Q4: What role does the ubiquitin system play in immune signaling and protein homeostasis? The ubiquitin system is a crucial post-translational modification process that regulates innate and adaptive immune responses. It involves a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that attach the small protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins. Different types of ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48, K63, M1-linear) determine the fate of the substrate, such as proteasomal degradation or activation of signaling pathways in response to stimuli like TNF or IL-1β. Tight regulation of this system by E3 ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) is essential for maintaining immune activation and self-tolerance [15].

Troubleshooting Guides for HCP and Immunogenicity Assays

Guide 1: Troubleshooting High Background in HCP ELISA

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient washing | Increase the number of washes; add a 30-second soak step between washes; ensure plates are drained completely [16] [17] [18]. |

| Non-specific antibody binding | Ensure a proper blocking step is included using a suitable buffer (e.g., 5-10% serum). Use affinity-purified antibodies [17]. |

| Contaminated buffers or reagents | Prepare fresh buffers and reagents. Ensure substrate is not exposed to light [17]. |

| Detection reagent concentration too high | Titrate the detection antibody to find the optimal working concentration [17]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Poor Replicate Data and Assay Reproducibility

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inconsistent pipetting | Calibrate pipettes; ensure tips are tightly sealed; thoroughly mix all reagents and samples before use [17]. |

| Insufficient or uneven washing | Check that all wells are filling and aspirating evenly. If using an automated washer, ensure all ports are clean [18]. |

| Edge effects | Use plate sealers during all incubations to prevent evaporation. Avoid stacking plates to ensure even temperature distribution [16] [17]. |

| Variations in incubation temperature or time | Adhere strictly to recommended incubation times and temperatures. Avoid areas with environmental fluctuations [16] [18]. |

Guide 3: Investigating Weak or No Signal

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Reagents not at room temperature | Allow all reagents to sit on the bench for 15-20 minutes before starting the assay [16]. |

| Incorrect storage or expired reagents | Double-check storage conditions (typically 2-8°C) and confirm all reagents are within their expiration dates [16]. |

| Capture antibody did not bind to plate | Ensure an ELISA plate (not a tissue culture plate) is used. Dilute the coating antibody in PBS without carrier proteins [16] [18]. |

| Wash buffer contains sodium azide | Avoid sodium azide in wash buffers as it can inhibit HRP activity [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Advanced HCP Characterization

Protocol 1: Orthogonal HCP Analysis using Mass Spectrometry

Purpose: To identify and quantify individual HCP species in a biologic drug substance, complementing ELISA data.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Desalt and digest the protein sample (e.g., final drug substance) using a protease like trypsin.

- Chromatography: Separate the resulting peptides using liquid chromatography (LC).

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze eluted peptides using shotgun MS/MS. The mass spectrometer fragments the peptides and identifies them by matching the fragmentation patterns to protein databases.

- Data Analysis: Use bioinformatics software to identify the HCPs present and perform semi-quantification based on spectral counts or peak areas [12].

Key Materials:

- LC-MS/MS system

- Trypsin for protein digestion

- Bioinformatics software for protein database search

Protocol 2: Evaluating ELISA Immunoreagent Coverage by IAC-MS

Purpose: To identify which HCPs in a sample are not recognized ( gaps ) by the polyclonal antibodies used in an HCP-ELISA.

Methodology:

- Immunoaffinity Capture: Incubate the drug substance sample with the purified polyclonal antibodies used in the ELISA.

- Washing: Remove unbound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the antibody-bound HCPs.

- MS Analysis: Identify the eluted HCPs using mass spectrometry (as in Protocol 1).

- Gap Analysis: Compare the list of HCPs identified in the original sample (via direct MS) with the list of HCPs that were captured by the pAbs. HCPs present in the original sample but absent from the captured fraction represent detection gaps in the ELISA [12].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Insights into HCP and Immunogenicity

Table 1: Immunogenicity (ADA) Rates of Selected Therapeutic mAbs

This table illustrates the variability in immunogenicity across different antibody therapeutics, underscoring the need for robust detection and mitigation strategies [13].

| mAb | Target | Type | ADA Rate Range (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab | TNF-α | Human | 3 – 61 |

| Alemtuzumab | CD52 | Humanized | 29 – 83 |

| Bevacizumab | VEGF-A | Humanized | 0.2 – 0.6 |

| Brolucizumab | VEGF-A | Human (scFv) | 53 – 76 |

| Daratumumab | CD38 | Human | 0 |

| Panitumumab | EGFR | Human | 0.5 – 5.3 |

Table 2: HCP Levels and Impact in an AAV Gene Therapy Study

This table summarizes data from a study investigating the impact of HCP levels in adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector lots, showing a quantitative difference in HCP content and a potential link to a safety outcome [19].

| Vector Lot Designation | Residual HCP (ng/mL) | Full/Empty Capsid Ratio (%) | Key Finding: Chorioretinal Atrophy (CRA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low HCP (L1) | 36.9 | 99.5 | Baseline CRA lesion size |

| High HCP 1 (H1) | 1433.7 | 98.5 | Significantly larger CRA lesions (P = 0.001–0.048) |

| High HCP 2 (H2) | 582.0 | 96.0 | Data consistent with H1 trend |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Process-Specific HCP ELISA | The gold-standard, high-throughput method for quantifying total HCP levels during process development and product release, though limited by immunoreagent coverage [12]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | An orthogonal method for identifying and quantifying individual HCPs. Critical for risk assessment, process understanding, and evaluating ELISA coverage [12]. |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Used to detect different forms of ubiquitination (e.g., K48, K63, linear chains) in Western blot or immunofluorescence to study immune signaling pathways [15]. |

| PROTABs (Proteolysis-Targeting Antibodies) | A novel technology that tethers a cell-surface E3 ubiquitin ligase to a transmembrane target protein, inducing its degradation. This represents a new application for antibody-based targeting of the ubiquitin system [20]. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Chemical tools (e.g., PR619) used to investigate the role of deubiquitination in cellular processes. Inhibition can induce immunogenic cell death, relevant for cancer research [21]. |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

ELISA HCP Detection Blind Spot

HCP Risk Mitigation Strategy

Ubiquitin-Mediated Immune Signaling

The development of high-affinity, site-specific ubiquitin antibodies represents a significant frontier in molecular biology and therapeutic research. The central challenge in this field stems from the weak immunogenicity of ubiquitin, a small 76-amino acid protein that is highly conserved across eukaryotic organisms [8]. This conservation means the immune system often fails to recognize ubiquitin as a foreign antigen, leading to difficulties in generating potent, specific antibodies through conventional methods. Furthermore, the dynamic and complex nature of ubiquitination—where ubiquitin molecules can form eight distinct polymer chains (homotypic) or mixed (heterotypic) linkages—creates a demand for antibodies that can distinguish between these specific forms with high precision [22] [6]. The scientific and therapeutic necessity to overcome these challenges is clear: such advanced tools are critical for accurately deciphering the ubiquitin code, understanding its role in diseases like cancer and neurodegeneration, and developing targeted therapies [8] [23].

Scientific Foundations: Ubiquitin Biology and Antibody Applications

The Ubiquitin Conjugation System

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification governed by a precise enzymatic cascade. The process begins with an E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, which activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Finally, an E3 ubiquitin ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin to a specific substrate protein [22]. Ubiquitin itself can be conjugated to other ubiquitin molecules through one of its seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or its N-terminal methionine (M1), creating a diverse array of polyubiquitin chains. Each chain type can signal different fates for the modified protein; for example, K48-linked chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains often function in DNA repair and inflammatory signaling [22].

Critical Applications in Research and Diagnostics

High-quality ubiquitin antibodies are indispensable tools across multiple domains of biological research and diagnostics. Their primary applications include:

- Mechanistic Disease Studies: Ubiquitin antibodies enable the detection of specific ubiquitin chain linkages involved in pathological processes. For instance, recent research published in Cell Reports utilized these tools to demonstrate how the RSK1 kinase reprograms the ubiquitin pathway to promote immune suppression in cancer by triggering K33-linked polyubiquitination of cGAS [23].

- Therapeutic Development: In drug discovery, these antibodies are used to monitor target engagement and the effects of therapeutic interventions on the ubiquitin-proteasome system. They are vital for developing and characterizing new classes of drugs, such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) [8].

- Diagnostic and Prognostic Tools: In clinical settings, the detection of specific ubiquitin signatures can serve as biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis. For example, the levels and phosphorylation status of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2L6 have been correlated with immune infiltration and patient response to therapy in cancer [23].

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: My ubiquitin antibody shows no signal in Western blot. What could be wrong? A: A lack of signal often results from protein degradation, improper antibody dilution, or epitope masking. First, verify sample quality by ensuring quick processing and adding protease inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to preserve ubiquitin conjugates [22]. Second, titrate your antibody; the suggested concentration in the manual is a starting point. High background may require less antibody, while no signal may require more [24]. Finally, consider antigen retrieval; for formalin-fixed samples, heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) may be necessary to expose hidden epitopes [25].

Q2: Why does my antibody work in Western blot but not in immunofluorescence (IF)? A: This discrepancy typically indicates that the antibody's epitope is inaccessible in the native protein structure. Antibodies raised against short peptide sequences may not recognize the full-length protein when it is folded into its native conformation with complex secondary and tertiary structures [24]. Consider using an antibody validated for IF or attempting different permeabilization methods (e.g., detergent vs. alcohol-based) [11].

Q3: How should I properly store and handle ubiquitin antibodies to maintain functionality? A: Proper storage is critical for antibody longevity. For concentrated stocks, follow the manufacturer's instructions. Generally, antibodies can be stored at 2-8°C for up to a month. For long-term storage, aliquot and freeze at -20°C in a non-frost-free freezer to avoid damaging temperature fluctuations during auto-defrost cycles [24]. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Once diluted, antibodies are less stable and should be used immediately or stored for no more than a day; do not re-freeze diluted antibodies [24].

Q4: What are the best practices for distinguishing polyubiquitination from multi-mono-ubiquitination? A: To distinguish between these forms, you must use linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies in combination with enzymatic assays. The recommended protocol involves an in vitro ubiquitin conjugation reaction followed by Western blotting with linkage-specific antibodies [11]. Furthermore, advanced enrichment techniques like the OtUBD protocol, which uses a high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain under native or denaturing conditions, can help separate different ubiquitinated forms before detection [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: High Background Staining in Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

- Potential Cause: Non-specific antibody binding or insufficient blocking.

- Solution: Optimize blocking conditions by using a protein block (e.g., normal serum) and include a detergent like Tween-20 in wash buffers [11]. Always include the appropriate controls: a no-primary-antibody control and a negative control probe (e.g., bacterial dapB) to distinguish specific signal from background [25].

Issue: Inconsistent Results Between Experiments

- Potential Cause: Improper antibody handling leading to degradation or aggregation.

- Solution: Always aliquot antibodies to minimize freeze-thaw cycles. Gently mix thawed antibodies—do not vortex. After dilution, do not store for extended periods as proteins at low concentrations can adsorb to container walls and denature [24]. Ensure consistent sample preparation and antigen retrieval conditions across all experiments.

Issue: Antibody Fails to Recognize Native Protein

- Potential Cause: The epitope is linear and buried within the protein's three-dimensional structure.

- Solution: This is a common limitation for antibodies generated against peptide sequences. Consider using an antibody generated against the full-length native protein or employing an alternative application, such as Western blotting under denaturing conditions, where the epitope may be exposed [24].

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol: Enriching Ubiquitinated Proteins with OtUBD Affinity Resin

The OtUBD (from Orientia tsutsugamushi) protocol provides a versatile and economical method for enriching mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins from complex cell lysates, superior to traditional methods like TUBEs for detecting monoubiquitination [22].

Materials & Reagents

- Plasmids: pRT498-OtUBD or pET21a-cys-His6-OtUBD (Addgene #190089, #190091)

- Lysis Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail.

- OtUBD Elution Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2% SDS.

- DNase I

- SulfoLink Coupling Resin

Step-by-Step Workflow

- Resin Preparation: Express the recombinant OtUBD protein and immobilize it on SulfoLink coupling resin. Block any remaining reactive sites and wash the resin extensively [22].

- Lysate Preparation: Harvest yeast or mammalian cells. Resuspend the cell pellet in lysis buffer. For yeast cells, mechanical disruption with glass beads is often necessary. Clarify the lysate by centrifugation to remove insoluble debris. Treat with DNase I to reduce viscosity [22].

- Affinity Pulldown: Incub the clarified lysate with the OtUBD affinity resin for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Washing: Pellet the resin and wash several times with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins using a denaturing buffer containing SDS for downstream applications like immunoblotting or liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [22].

Note: For a "native workflow" that co-purifies proteins that interact with ubiquitin or ubiquitinated proteins, use non-denaturing buffers without SDS. For a "denaturing workflow" that specifically isolates covalently ubiquitinated proteins, include denaturants like urea or SDS [22].

Protocol: Ubi-Tagging for Site-Specific Antibody Conjugation

Ubi-tagging is a novel technique that exploits the ubiquitination enzymatic cascade for the site-directed, multivalent conjugation of antibodies, enabling the creation of homogeneous antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and bispecific engagers [6].

Key Reagents

- E1 Activating Enzyme

- E2-E3 Fusion Enzyme (e.g., gp78RING-Ube2g2 for K48 linkage)

- Donor Ubi-tag (Ubdon): A ubiquitin tag with a free C-terminal glycine and a lysine-to-arginine mutation (e.g., K48R) to prevent homodimerization.

- Acceptor Ubi-tag (Ubacc): A ubiquitin tag with the corresponding lysine residue (e.g., K48) and a blocked C-terminus (e.g., ΔGG or a His-tag).

Conjugation Procedure

- Incubation: Mix the ubi-tagged antibody (e.g., Fab-Ub(K48R)don) with a 5-fold molar excess of the payload-functionalized Ubacc (e.g., Rho-Ubacc-ΔGG) in the presence of E1 and the linkage-specific E2-E3 fusion enzyme.

- Reaction Monitoring: Allow the reaction to proceed for 30 minutes at room temperature. Monitor conversion by SDS-PAGE.

- Purification: Purify the conjugate (e.g., Rho-Ub2-Fab) using affinity chromatography (e.g., protein G). The efficiency of this reaction typically exceeds 90% [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents for advanced ubiquitin research, as highlighted in the search results.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Ubiquitin Research

| Reagent Name | Function/Application | Key Features & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| OtUBD Affinity Resin [22] | Enrichment of mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates. | High-affinity (nanomolar Kd); works under native and denaturing conditions; more effective for monoubiquitin than TUBEs. |

| Engineered Ubiquitin Variants (UbVs) [26] | Intracellular inhibitors or activators of specific UPS components (e.g., DUBs). | Small, stable, and soluble; can be engineered for high affinity and absolute specificity against target domains like DUSPs. |

| Ubi-Tagging System [6] | Site-specific, multivalent conjugation of antibodies and nanobodies. | Enables homogeneous conjugate formation in <30 min with >90% efficiency; modular and linkage-specific. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detection of specific polyubiquitin chain types (e.g., K48, K63) in Western blot, IHC, and IF. | Critical for deciphering the ubiquitin code; requires rigorous validation for specificity. |

| Ubiquitin Conjugation Enzymes (E1, E2, E3) [6] | In vitro ubiquitination assays and techniques like ubi-tagging. | Recombinantly purified; available as specific E2-E3 fusions to dictate linkage type. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Accurate interpretation of experimental data is fundamental. The table below provides a framework for quantifying results from ubiquitin detection assays, such as the RNAscope ISH assay, which can be adapted for semi-quantitative analysis of ubiquitin mRNA or protein staining patterns [25].

Table 2: Semi-Quantitative Scoring Guidelines for Ubiquitin Detection Assays

| Score | Staining Criteria (Dots per Cell) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No staining or <1 dot/ 10 cells | Negative / Expression not detected |

| 1 | 1-3 dots/cell | Low expression level |

| 2 | 4-9 dots/cell; very few dot clusters | Moderate expression level |

| 3 | 10-15 dots/cell; <10% dots in clusters | High expression level |

| 4 | >15 dots/cell; >10% dots in clusters | Very high expression level |

Advanced Methodologies for Generating and Applying Site-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

What are the primary causes of weak immunogenicity in ubiquitin antibodies, and how can synthetic strategies overcome this?

Weak immunogenicity in ubiquitin antibodies primarily stems from the instability of the native isopeptide linkage and the large size of the ubiquitin protein, which complicates antigen presentation [27]. The native ubiquitin-lysine isopeptide bond is readily cleaved by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) present in biological systems, leading to the degradation of the immunogen before a robust immune response can be mounted [27].

Synthetic solutions involve designing proteolytically stable antigen conjugates:

- Stable Bond Isosteres: Replace the native isopeptide bond with a non-hydrolyzable triazole isostere using click chemistry. This mimic preserves the overall structure of the ubiquitin-lysine environment while resisting cleavage by DUBs [27].

- Full-Length Ubiquitin Antigens: Using full-length, synthetically derived ubiquitin in a stable form for immunization increases the chance of exposing a site-specific epitope, leading to higher-quality antibodies [27].

- The Ubi-Tagging Platform: This method uses the cell's own ubiquitination machinery or recombinant enzymes to create defined conjugates. It allows for rapid (approx. 30 minutes) and highly efficient (93-96%) site-specific conjugation of ubiquitin to various payloads, ensuring homogeneous and stable conjugates for immunization [28] [6].

My ubiquitin-peptide conjugates are insoluble or prone to aggregation. How can I improve their biophysical properties?

Poor solubility, especially when conjugating hydrophobic peptides or small molecules, is a common hurdle. The ubi-tagging platform has demonstrated success in mitigating these issues.

- Problem: Hydrophobic antigenic peptides can cause aggregation when conjugated to targeting antibodies (e.g., nanobodies), reducing functional efficacy [28] [6].

- Solution: Employ the ubi-tagging strategy for conjugation. Research has shown that ubi-tagging significantly improves the solubility of challenging nanobody-antigen conjugates, reduces aggregation, and increases functional efficacy in vivo compared to other methods like sortagging [28] [6]. The platform's design appears to enhance the overall biophysical properties of the final conjugate.

How can I achieve site-specific conjugation for homogeneous ubiquitin-peptide conjugates?

Traditional chemical conjugation often results in heterogeneous mixtures. For homogeneity, use enzymatic conjugation strategies that target specific sites.

Ubi-Tagging Methodology [28] [6]: This method requires three key components for controlled heterodimer formation:

- Donor Ubi-tag (Ubdon): A ubiquitin fusion (e.g., to an antibody) with a free C-terminal glycine and a mutated conjugating lysine (e.g., K48R) to prevent homodimer formation.

- Acceptor Ubi-tag (Ubacc): A ubiquitin unit carrying the corresponding conjugation lysine (e.g., K48) but with a blocked C-terminus (e.g., via a His-tag or molecular cargo).

- Linkage-Specific Enzymes: A combination of recombinant E1 activating enzyme and a specific E2-E3 fusion enzyme (e.g., gp78RING-Ube2g2 for K48 linkage).

Protocol Summary:

- Incubate your Fab-Ub(K48R)don (10 µM) with a fivefold excess of your peptide-Ubacc-ΔGG (50 µM).

- Add the ubiquitination enzymes (0.25 µM E1, 20 µM E2-E3).

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Purify the conjugate using standard methods like affinity chromatography (e.g., protein G for antibodies) [6]. This protocol consistently achieves high efficiency and homogeneity.

What quality control metrics are critical for validating stable ubiquitin-peptide conjugates?

Rigorous quality control is essential to ensure conjugate integrity and function. The table below summarizes key metrics and methods based on cited research.

Table 1: Key Quality Control Metrics for Ubiquitin-Peptide Conjugates

| Metric | Description | Method of Analysis | Desired Outcome (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conjugation Efficiency | Percentage of starting material converted to the desired conjugate. | SDS-PAGE, ESI-TOF Mass Spectrometry [6] | >90% consumption of starting material; single band/product of expected molecular weight [6]. |

| Conjugate Stability | Resistance to enzymatic degradation and maintenance of structural integrity. | Incubation with DUBs; Thermal Shift Assay [6] [27] | Resistance to DUB cleavage; infliction temperature (e.g., ~75°C for a Fab conjugate) unchanged post-conjugation [6] [27]. |

| Specificity & Function | Ability to bind the target antigen and perform its intended biological role. | Flow Cytometry, Cell-Based Activity Assays [6] | Comparable antigen-binding to parental antibody; superior T-cell activation in functional assays [28] [6]. |

| Solubility & Aggregation | Level of soluble, non-aggregated conjugate. | Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [28] | Monomeric peak in SEC; reduced aggregation compared to conjugates made via other methods [28]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and their functions for developing site-specific ubiquitin antibodies and conjugates, as derived from the referenced studies.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Synthetic Ubiquitin-Peptide Conjugate Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Ubiquitination Enzymes (E1, E2-E3 fusions) | Catalyze the site-specific ligation between donor and acceptor ubi-tags in the ubi-tagging platform [6]. |

| Synthetic Ubiquitin Derivatives (e.g., Ubacc-ΔGG) | Serve as stable, chemically defined building blocks for conjugation. Can be functionalized with peptides, fluorophores, or other payloads [6] [27]. |

| Non-hydrolyzable Ub-Peptide Antigens (Triazole Isostere) | Used as immunogens to generate site-specific ubiquitin antibodies that are not cleaved by deubiquitinating enzymes [27]. |

| Computational Protein Design Tools (e.g., ProteinMPNN, RFDiffusion) | Aid in the de novo design of peptide binders and protein scaffolds, enabling targeting of "undruggable" or disordered proteins [29] [30]. |

| Deubiquibodies (duAbs) | Chimeric proteins (fusion of designed peptide guide to OTUB1 deubiquitinase) used for Targeted Protein Stabilization (TPS) research [29]. |

Experimental Workflow & Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for Generating Site-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies

This diagram outlines the key steps in the development and validation of site-specific ubiquitin antibodies, from antigen design to final application.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Site-Specific Ubiquitin Antibody Generation

Ubi-Tagging Platform Mechanism

This diagram illustrates the core components and mechanism of the ubi-tagging platform for creating site-specific conjugates.

Diagram Title: Ubi-Tagging Conjugation Mechanism

The ubiquitination machinery, comprising the E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes, offers a powerful and natural platform for the controlled and site-specific conjugation of proteins. This enzymatic cascade, central to post-translational modification, facilitates the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target substrates. Recent advances have demonstrated its utility far beyond its physiological role, particularly in generating well-defined protein conjugates for research and therapeutic applications. However, researchers often face significant challenges, including the weak immunogenicity of ubiquitin and the transient nature of ubiquitination events. This technical support center is designed within the context of overcoming these hurdles, providing targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to empower scientists in harnessing this complex system effectively.

The following diagram illustrates the core three-step enzymatic pathway of ubiquitination, which can be leveraged for controlled conjugation experiments.

Core Concepts and Reagent Toolkit

Fundamental Mechanism

The ubiquitination process is a tightly regulated, three-step enzymatic cascade [31] [32]:

- Activation (E1): A ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) utilizes ATP to form a high-energy thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin.

- Conjugation (E2): The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to a cysteine residue on a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), forming another thioester bond.

- Ligation (E3): Finally, a ubiquitin ligase (E3) facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine ε-amino group on the target protein substrate, forming a stable isopeptide bond. E3s are responsible for substrate specificity, and with over 600 in the human genome, they offer immense targeting potential [31] [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes essential reagents for studying and applying the ubiquitination machinery.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent | Function & Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner; the initial step of the cascade. | In vitro ubiquitination reconstitution assays [34]. |

| E2 Enzyme | Carries activated ubiquitin; works in concert with an E3 to modify specific substrates. | Determining specific E2/E3 pairing requirements for a target protein [34] [35]. |

| E3 Ligase | Provides substrate specificity; numerous families exist (RING, HECT, RBR) [33]. | Targeted ubiquitination of a protein of interest; a key tool for controlled conjugation. |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | Ubiquitin with specific lysine-to-arginine mutations (e.g., K48R, K63R). | Directing the formation of specific polyubiquitin chain linkages [6]. |

| Ubiquitin-Trap | A high-affinity nanobody (VHH) coupled to beads for pulldown assays. | Enriching ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins from complex cell lysates for detection [36]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Small molecules that block the activity of the proteasome (e.g., MG-132). | Preserving and enhancing the detection of ubiquitinated proteins in cells by preventing their degradation [36]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies that recognize a specific ubiquitin chain linkage (e.g., K48-only, K63-only). | Determining the type of polyubiquitin chain present on a substrate via Western blot [36]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Failure to Detect Ubiquitinated Substrate

Observed Issue: In an in vitro conjugation assay or cell-based experiment, the expected ubiquitinated products (visible as a smear or ladder on a Western blot) are not detected.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Incomplete Reaction Mixture

- Solution: Verify that all essential components are included in the reaction. A functional in vitro reaction requires E1, E2, E3, ubiquitin, ATP, and your substrate in an appropriate buffer [34]. Always include a negative control without ATP to confirm the reaction's ATP dependence.

- Cause 2: Low Abundance or Transient Modification

- Solution: Enhance detection by using proteasome inhibitors like MG-132 (e.g., 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) in cell-based experiments to prevent the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins [36]. For in vitro assays, ensure enzyme concentrations are sufficient (e.g., 100 nM E1, 1 µM E2, 1 µM E3) and extend the incubation time up to 60 minutes at 37°C [34].

- Cause 3: Non-Specific or Weak Ubiquitin Antibodies

- Solution: This is a central challenge in the field. To overcome the weak immunogenicity and non-specificity of many ubiquitin antibodies [36]:

- Use high-affinity tools like the Ubiquitin-Trap for immunoprecipitation to enrich for ubiquitinated proteins prior to Western blotting, which drastically improves the signal-to-noise ratio [36].

- Validate your Western blot results with an antibody specific for your target protein to confirm the higher molecular weight species are indeed your ubiquitinated substrate [34].

- Solution: This is a central challenge in the field. To overcome the weak immunogenicity and non-specificity of many ubiquitin antibodies [36]:

Problem: High Background or Non-Specific Ubiquitination

Observed Issue: A ubiquitin smear is present in negative controls, or the E3 ligase appears to be ubiquitinated instead of the target substrate (autoubiquitination).

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: E3 Ligase Autoubiquitination

- Solution: This is a common phenomenon. To distinguish autoubiquitination from substrate ubiquitination, run a control reaction without your substrate. Analyze the products by Western blot using both anti-ubiquitin and anti-E3 ligase antibodies [34].

- Cause 2: Contaminated or Impure Enzyme Preparations

Problem: Inability to Control Conjugation Specificity

Observed Issue: The conjugation reaction produces heterogeneous products when a specific, homogeneous conjugate is desired.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Uncontrolled Polyubiquitin Chain Formation

- Solution: To generate defined conjugates, use engineered ubiquitin components. For example, in the "ubi-tagging" technique [6]:

- Use a donor ubiquitin (Ubdon) with a free C-terminus but a mutated lysine (e.g., K48R) to prevent chain elongation.

- Use an acceptor ubiquitin (Ubacc) with a reactive lysine (e.g., K48) but a blocked C-terminus (e.g., ΔGG or a His-tag).

- Combine these with linkage-specific E2-E3 enzyme pairs to direct conjugation with high precision.

- Solution: To generate defined conjugates, use engineered ubiquitin components. For example, in the "ubi-tagging" technique [6]:

Advanced Application: The Ubi-Tagging Workflow

The ubi-tagging method is a cutting-edge application of the ubiquitination machinery for creating site-specific protein conjugates. The workflow below details this innovative process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my ubiquitinated proteins appear as a smear on a Western blot, and is this normal?

A: Yes, this is typically normal and expected. A smear represents a heterogeneous mixture of your target protein with varying numbers of ubiquitin molecules attached (mono-, di-, tri-ubiquitination, etc.). The Ubiquitin-Trap, for instance, pulls down all these species, resulting in a smeared appearance on a gel [36]. If a discrete ladder is expected but a smear is observed, it may indicate non-specific activity or degradation.

Q2: My ubiquitin antibody is not specific and detects many non-specific bands. What can I do?

A: This is a well-known challenge due to ubiquitin's small size and high conservation. We recommend two approaches:

- Immunoprecipitation-based Enrichment: Use a high-affinity reagent like the Ubiquitin-Trap to isolate ubiquitinated proteins from your lysate first. This enrichment step significantly reduces background in subsequent Western blots [36].

- Orthogonal Validation: Always probe the same Western blot membrane with an antibody against your specific protein of interest. The co-localization of signals from both antibodies confirms the identity of the ubiquitinated species [34].

Q3: How can I determine which lysine residue on my substrate is being ubiquitinated?

A: Standard in vitro ubiquitination assays can identify if a protein is ubiquitinated but not the specific site. To map the exact lysine residue, you would need to follow up with techniques such as mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of the modified protein. The in vitro assay protocol can be terminated with DTT or EDTA instead of sample buffer if the products are intended for downstream applications like MS [34].

Q4: Can I use the ubiquitination machinery to conjugate non-protein molecules?

A: Yes, recent advances show this is possible. The ubi-tagging technique has been successfully used to conjugate fully synthetic ubiquitin derivatives carrying payloads like fluorescent dyes and antigenic peptides to antibodies and nanobodies [6]. This demonstrates the remarkable versatility of the system for bioconjugation.

Q5: What are the key advantages of using the enzymatic ubiquitination system over chemical conjugation methods?

A: The primary advantages are site-specificity and homogeneity. Enzymatic conjugation, such as ubi-tagging, occurs at a defined lysine residue on the acceptor ubiquitin, leading to a uniform product. In contrast, traditional chemical conjugation (e.g., via lysine or cysteine residues) often results in a heterogeneous mixture of products with variable stoichiometry and activity, which can compromise functionality and pharmacokinetics [6].

Ubi-tagging represents a modular and versatile technique for site-directed protein conjugation that addresses a critical challenge in biomedical engineering: obtaining homogeneous multimeric antibody conjugates. This innovative platform utilizes the small protein ubiquitin (Ub) as a fusion tag, enabling rapid and efficient conjugation of various molecular cargo—including antibodies, antibody fragments, nanobodies, peptides, and small molecules—within remarkably short timeframes of approximately 30 minutes [6] [37].

The technology harnesses the natural ubiquitination machinery, comprising ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes, to create precise, site-specific conjugates with an impressive average efficiency of 93-96% for reactions involving ubi-tagged antibodies [28] [37]. This breakthrough addresses fundamental limitations of conventional antibody-conjugation strategies that often result in heterogeneous products with limited control over modification sites and numbers, potentially compromising antibody functionality and pharmacokinetics [6].

Core Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Fundamental Principles of Ubi-Tagging

The ubi-tagging approach relies on three essential components for controlled heterodimer formation. First, it requires linkage-specific ubiquitination enzymes (such as those specific for lysine-48 or K48 linkage). Second, a donor ubi-tag (Ubdon) must feature a free C-terminal glycine while containing a mutation at the conjugating enzyme-specific lysine residue (e.g., K48R) to prevent homodimer formation and polymerization. Third, an acceptor ubi-tag (Ubacc) must contain the corresponding conjugation lysine residue (e.g., K48) while having an unreactive C-terminus achieved through removal of the C-terminal di-glycine motif (ΔGG) or blocking with a His-tag or molecular cargo [6] [37].

Ubi-tagged proteins can be produced through multiple approaches. For Fab' fragments, researchers have successfully applied a CRISPR/HDR genomic engineering approach to hybridomas or utilized transient expression systems [6] [37]. Meanwhile, ubi-tagged peptides and fluorophores can be synthesized via solid-phase peptide synthesis methods [6].

Standard Conjugation Protocol

The following workflow details a standard ubi-tagging conjugation procedure for site-specific fluorescent labeling of Fab' fragments:

Reaction Setup: Combine 10 µM of Fab-Ub(K48R)don with a fivefold excess (50 µM) of acceptor ubiquitin tagged with payload (e.g., Rhodamine-Ubacc-ΔGG) in an appropriate reaction buffer [6] [37].

Enzyme Addition: Add ubiquitination enzymes at optimized concentrations—0.25 µM E1 and 20 µM of the K48-specific E2-E3 fusion protein gp78RING-Ube2g2 [6] [37].

Incubation: Conduct the reaction at room temperature or 37°C for 30 minutes with gentle mixing [6] [37].

Purification: Purify the conjugate (e.g., Rhodamine-Ub2-Fab) using protein G affinity chromatography to remove enzymes and unreacted components [6].

Validation: Analyze the product using techniques such as SDS-PAGE, electrospray ionization time-of-flight (ESI-TOF) mass spectrometry, and functional assays to confirm conjugation efficiency and antigen-binding capability [6] [37].

Table: Key Reaction Components for Ubi-Tagging Conjugation

| Component | Role | Example/Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Ubi-Tag | Contains free C-terminal glycine, specific lysine mutation | Fab-Ub(K48R)don at 10 µM |

| Acceptor Ubi-Tag | Contains conjugation lysine, blocked C-terminus | Rhodamine-Ubacc-ΔGG at 50 µM |

| E1 Enzyme | Ubiquitin activation | 0.25 µM |

| E2-E3 Fusion Enzyme | Linkage-specific conjugation | gp78RING-Ube2g2 at 20 µM |

| Reaction Time | Completion period | 30 minutes |

| Reaction Efficiency | Conversion rate | 93-96% |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Low Conjugation Efficiency

Problem: Incomplete consumption of donor ubi-tagged protein after 30-minute reaction time.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Enzyme Activity: Verify enzyme quality and storage conditions. Ensure E1 and E2-E3 enzymes are aliquoted and stored at recommended temperatures without repeated freeze-thaw cycles [24].

- Incorrect Molar Ratios: Maintain optimal donor-to-acceptor ratio of 1:5 to drive reaction completion [6].

- Ubiquitin Tag Mutations: Confirm donor ubiquitin contains appropriate lysine-to-arginine mutation (e.g., K48R) and acceptor ubiquitin has blocked C-terminus (ΔGG or His-tag) [6] [37].

- Protein Stability Issues: Check structural integrity of ubi-tagged proteins using thermal shift assays; ubi-tagged Fab' fragments typically show infliction temperature of ~75°C [6].

Poor Solubility or Aggregation

Problem: Precipitation or aggregation of ubi-tagged conjugates, particularly with hydrophobic payloads.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Hydrophobic Payloads: Ubi-tagging demonstrates improved handling of hydrophobic peptides compared to alternative methods like sortagging. Consider introducing hydrophilic linkers or optimizing buffer conditions [28].

- Protein Concentration: Avoid excessively high concentrations during conjugation. If necessary, dilute reaction mixture and extend incubation time [24].

- Buffer Optimization: Supplement with compatible detergents or solubility enhancers, ensuring they don't interfere with enzymatic activity [38].

Impaired Antigen Binding

Problem: Conjugated antibody shows reduced or lost antigen-binding capability.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Epitope Masking: Ensure ubiquitin fusion doesn't sterically hinder antigen-binding region. Test different fusion sites or incorporate flexible linkers [39].

- Conformation Alteration: Verify proper folding of conjugated antibody using circular dichroism or similar techniques [6].

- Validation: Always compare staining patterns to parental antibody using flow cytometry or immunofluorescence; properly conjugated ubi-tagged Fab' should maintain equivalent binding profiles [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Ubi-Tagging Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Enzymes | E1, E2-E3 fusion (gp78RING-Ube2g2) | Catalyze site-specific conjugation | Use linkage-specific enzymes for controlled conjugation [6] |

| Expression Systems | CRISPR/HDR-engineered hybridomas, transient expression | Production of ubi-tagged antibodies | Enables genetic fusion of ubiquitin tags [6] [37] |

| Synthetic Ubiquitin | Chemically synthesized Ub derivatives with dyes/peptides | Provide customizable conjugation payloads | Solid-phase peptide synthesis compatible [6] |

| Purification Resins | Protein G beads, affinity matrices | Isolation of conjugated products | Protein A recommended for rabbit IgG, Protein G for mouse IgG [39] |

| Stabilization Agents | BSA, glycerol | Maintain antibody stability during storage | Prevents aggregation and activity loss [24] |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-ubiquitin monoclonal antibodies | Verification of successful conjugation | Ensure compatibility with application (IHC, WB, flow) [24] |

Ubi-Tagging Workflow and Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the core ubi-tagging conjugation mechanism for generating site-specific antibody conjugates:

FAQs on Ubi-Tagging Technology

What are the primary advantages of ubi-tagging over traditional conjugation methods? Ubi-tagging offers several significant advantages: (1) It achieves highly homogeneous conjugates with precise site-specificity, overcoming the heterogeneity of traditional lysine or cysteine conjugation; (2) Reactions are remarkably fast (approximately 30 minutes) compared to hours or days required for other enzymatic methods; (3) The platform demonstrates exceptional efficiency (93-96% conversion); (4) It enables controlled multivalency through specific ubiquitin linkage types; and (5) It maintains antibody functionality and stability post-conjugation [6] [28] [37].

Can ubi-tagging generate multimeric antibody formats beyond simple conjugates? Yes, ubi-tagging can produce various multimeric formats. Using wildtype ubiquitin fusions (Fab-UbWT), researchers have generated multimers up to the 11th order and beyond within 30 minutes. More importantly, the technology enables controlled assembly of specific architectures like bivalent monospecific Fab2-Ub2 dimers through careful selection of ubiquitin mutants, all without compromising thermostability [6] [37].

How does ubi-tagging address challenges with hydrophobic or poorly soluble payloads? Studies demonstrate ubi-tagging particularly excels at conjugating hydrophobic, poorly soluble antigenic peptides. When compared directly to sortagging for dendritic-cell-targeted antigens, ubi-tagged conjugates showed enhanced solubility, reduced aggregation, and increased functional efficacy both in vitro and in vivo, leading to more potent T-cell responses [28].

What are the limitations of the ubi-tagging platform? The primary limitation involves the relatively large size of the ubiquitin tag (76 amino acids), which might constrain applications where minimal tagging is essential. Additionally, the system depends on recombinant ubiquitination enzymes, requiring appropriate production and storage capabilities. Researchers must also carefully control reaction conditions to prevent non-specific polymerization [28].

How should ubi-tagged antibodies be stored to maintain stability? For long-term storage, concentrated ubi-tagged antibodies should be aliquoted and stored at -80°C in non-frost-free freezers to prevent temperature fluctuations during defrost cycles. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. For short-term use (up to one month), antibodies can be stored at 2-8°C with stabilizing agents like BSA. Diluted working solutions should be prepared fresh for each use [24].

Ubiquitin-Antibody Fusion Design

The diagram below illustrates the strategic design of donor and acceptor ubi-tags for controlled conjugation:

Applications and Future Directions

Ubi-tagging has demonstrated significant utility in generating sophisticated therapeutic molecules. The technology has successfully produced tetravalent bispecific T-cell engagers with maintained functionality, highlighting its potential for cancer immunotherapy applications [6] [28]. Additionally, nanobody-antigen conjugates created via ubi-tagging have shown enhanced T-cell activation in dendritic cell-targeted vaccination approaches, outperforming state-of-the-art methods like sortagging in preclinical models [28] [37].

The integration of both recombinant ubi-tagged proteins and synthetic ubiquitin derivatives positions ubi-tagging as a versatile platform for iterative, site-directed multivalent conjugation. This opens exciting possibilities for developing next-generation antibody-based therapeutics, particularly in immune-oncology and autoimmune diseases, where precise targeting and controlled valency are paramount for therapeutic efficacy and safety [28].

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) serves as the primary proteolytic machinery in eukaryotic cells, responsible for the controlled degradation of intracellular proteins and the generation of peptides for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I antigen presentation [40]. CD8+ T-cell responses depend overwhelmingly on proteasome-dependent protein degradation and the subsequent presentation of oligopeptide products complexed with MHC class I molecules [40]. Immunoproteasomes, specialized proteasomal variants containing the inducible catalytic subunits β1i (LMP2), β2i (MECL-1), and β5i (LMP7), demonstrate enhanced efficiency in generating antigenic peptides for immune surveillance [40]. Research has established that fusion of antigens to ubiquitin (Ub) can target them to the proteasome, potentially circumventing weak immunogenicity and enhancing CD8+ T-cell responses against both dominant and subdominant epitopes [41]. This technical resource center addresses the experimental challenges and considerations in applying proteasome-targeting strategies to overcome weak immunogenicity in ubiquitin antibody research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Proteasome-Targeting Sequences

Q1: What is the fundamental mechanism by which ubiquitin fusion enhances epitope presentation?

Ubiquitin fusion operates as a targeting signal for the proteasome. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway typically degrades polyubiquitinated proteins. By creating a fusion construct where your antigen of interest is linked to ubiquitin, you are essentially marking that antigen for more efficient processing by the proteasome [41]. This enhanced degradation increases the supply of oligopeptides available for loading onto MHC class I molecules, thereby amplifying the subsequent CD8+ T-cell response [40].

Q2: Why might my ubiquitin-antigen fusion construct fail to enhance CD8+ T-cell responses?

Failures can occur if the ubiquitin constructs used are not optimized for mammalian systems. Early research often utilized rules for ubiquitin modification defined in yeast, which do not always function effectively in mammalian cells [41]. The failure is likely due to inadequate targeting of the antigen to the proteasome. Ensure that you are using mammalian-optimized ubiquitin genes in your fusion constructs to mediate enhanced CD8+ responses through successful proteasome targeting [41].

Q3: How does the immunoproteasome differ from the constitutive proteasome, and why does it matter for immunogenicity?

The constitutive proteasome, present in most cells, contains catalytic subunits β1, β2, and β5. The immunoproteasome, often elevated in immune cells and induced by proinflammatory stimuli like interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), substitutes these with β1i (LMP2), β2i (MECL-1), and β5i (LMP7) [40]. This substitution alters the cleavage preference of the proteasome, enhancing the generation of peptides with hydrophobic or basic C-termini, which are ideal for binding to MHC class I molecules. Consequently, immunoproteasomes are significantly more efficient at producing the antigenic repertoire for cytotoxic T-cell recognition [40].

Q4: Can enhancing antigen presentation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway overcome subdominant epitope responses?

Yes. A key application of ubiquitin fusion is to enhance responses against subdominant epitopes, which are typically less immunogenic. Research on the influenza virus nucleoprotein demonstrated that fusion to mammalian-optimized ubiquitin constructs successfully enhanced CD8+ T-cell responses against its refractory subdominant epitope in mice [41]. This strategy is particularly valuable for vaccine development where broader immune coverage is desired.

Troubleshooting Guides

Low T-Cell Responses Despite Ubiquitin Fusion

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No improvement in CD8+ T-cell response after Ub fusion. | Use of ubiquitin constructs optimized for yeast, not mammalian systems. | Redesign fusion constructs using mammalian-optimized ubiquitin genes [41]. |

| Weak response to a specific (subdominant) epitope. | Inefficient targeting and processing of the specific antigenic region. | Apply mammalian-optimized Ub fusion to enhance responses against refractory subdominant epitopes [41]. |

| Poor protein expression of the Ub-antigen fusion. | General protein expression or translation issues unrelated to targeting. | Verify that enhanced immunogenicity is due to proteasome targeting, not increased translation [41]. |

| Low immunogenicity of a native (wild-type) antigen. | inherent immune evasion or weak processing of the wild-type antigen. | Utilize ubiquitin fusion to circumvent weak immunogenicity driven by the native antigen's properties [41]. |

Quantifying Success: Immune Monitoring Assay Pitfalls

| Assay Type | Common Challenge | Solution & Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| ELISPOT | Low spot count or high background. | Use >95% viable cells, plate within 8h of blood collection, and let frozen PBMCs rest ≥1h post-thaw [42]. |

| ELISPOT | Contaminated PBMC layer affecting T-cell function. | Isolate PBMCs via Ficoll density gradient centrifugation with brake off during centrifugation to ensure a clean cell layer [42] [43]. |

| B-cell ELISPOT | Poor detection of antigen-specific memory B cells (MBCs). | Differentiate MBCs into antibody-secreting cells in vitro via a 6-day stimulation with R848 and IL-2 before plating [43]. |

| Cytokine Analysis | Inability to detect secretion from rare, antigen-specific cells. | Use single-cell resolution assays like ELISPOT over bulk solution assays like ELISA for detecting low-frequency immune responses [42]. |

Key Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Ubiquitin-Mediated Antigen Presentation Pathway

ELISPOT Assay Workflow for Immune Monitoring

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Proteasome-Targeting Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|