Strategies to Reduce Non-Specific Binding in Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment: A Guide for Reliable Proteomics

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize the enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins for proteomic analysis.

Strategies to Reduce Non-Specific Binding in Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment: A Guide for Reliable Proteomics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize the enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins for proteomic analysis. Non-specific binding is a major hurdle that can compromise data quality, leading to false positives and reduced sensitivity. We cover the foundational principles of ubiquitination complexity and the key sources of non-specific interactions. The content details robust methodological approaches, including affinity tags, antibodies, and ubiquitin-binding domains, highlighting protocols designed to enhance specificity. A dedicated troubleshooting section offers actionable strategies to optimize buffer conditions, resin selection, and sample handling. Finally, we outline rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of enrichment methods to ensure data reliability, concluding with future perspectives for biomedical and clinical research applications.

Understanding the Ubiquitination Landscape and Key Challenges in Specific Enrichment

Fundamental Ubiquitin Signaling Concepts & FAQs

What are the primary functional outcomes of different ubiquitin signals?

Ubiquitin signaling is highly complex, with diverse outcomes dictated by the type of ubiquitination and the specific lysine linkages within polyubiquitin chains. The table below summarizes the primary functional consequences of different ubiquitin signals [1]:

| Linkage Site | Ubiquitin Chain Length | Primary Downstream Signaling Event |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate-specific lysines | Monomer | Endocytosis, histone modification, DNA damage responses |

| K48 | Polymeric | Targeted protein degradation by the 26S proteasome |

| K63 | Polymeric | Immune responses, inflammation, lymphocyte activation, DNA repair, endocytosis |

| K6 | Polymeric | Antiviral responses, autophagy, mitophagy, DNA repair |

| K11 | Polymeric | Cell cycle progression, proteasome-mediated degradation |

| K27 | Polymeric | DNA replication, cell proliferation |

| K29 | Polymeric | Neurodegenerative disorders, Wnt signaling downregulation, autophagy |

| M1 (Linear) | Polymeric | Cell death and immune signaling (e.g., NF-κB activation) |

It is crucial to distinguish between poly-ubiquitination (multiple ubiquitins attached end-to-end to a single lysine residue) and multi-mono-ubiquitination (single ubiquitin molecules attached to multiple lysine residues), as they lead to different functional outcomes for the substrate protein [2].

What is the enzymatic cascade responsible for ubiquitin conjugation?

The ubiquitination process is a sequential, ATP-dependent enzymatic cascade [3] [4]:

- Activation (E1): A ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent process, forming a thioester bond between the C-terminal carboxyl group of ubiquitin and a cysteine residue in the E1 active site.

- Conjugation (E2): The activated ubiquitin is transferred to a cysteine residue of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) via a transesterification reaction.

- Ligation (E3): A ubiquitin-protein ligase (E3) catalyzes the final transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate protein, forming an isopeptide bond. E3 ligases provide substrate specificity, with hundreds existing in humans [3].

This process is reversible through the action of deubiquitinases (DUBs) [5] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment

A major challenge in ubiquitination research is the specific enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins away from non-specifically binding contaminants. The following table outlines common problems and solutions, framed within the context of reducing non-specific binding.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution & Recommended Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| High background; many non-specific proteins identified by MS. | Co-purification of endogenous His-rich proteins (when using His-tagged Ub). | Use tandem affinity tags (e.g., His-Biotin tags) for two-step purification [7]. Alternatively, use high-affinity nanobodies like the ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap (agarose or magnetic beads) designed for clean, low-background pulldowns under harsh washing conditions [1]. |

| Weak or no ubiquitination signal. | Low steady-state levels of ubiquitinated proteins due to active DUBs or proteasomal degradation. | Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132 at 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours prior to harvesting) to stabilize ubiquitin conjugates [1]. Note that overexposure can cause cytotoxicity. |

| Antibody shows non-specific bands or high background in Western blot. | Many ubiquitin antibodies are non-specific due to ubiquitin's small size and weak immunogenicity [1]. | Use high-quality, well-validated recombinant antibodies (e.g., Proteintech Ubiquitin Recombinant Antibody, 80992-1-RR) [1] or linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., K48-linkage specific antibody) [6]. |

| Inability to distinguish poly-ubiquitination from multi-mono-ubiquitination. | Both types of modification cause similar high molecular weight smears on a Western blot [2]. | Perform in vitro ubiquitination assays with Ubiquitin No K (all lysines mutated to arginine), which cannot form chains. High MW bands present only with wild-type Ub indicate poly-ubiquitination; bands present with both indicate multi-mono-ubiquitination [2]. |

| Uncertainty about the linkage type of a polyubiquitin chain. | Western blot smears do not reveal the specific lysine linkage used for chain assembly. | Perform in vitro ubiquitination assays using panels of ubiquitin mutants. Use Ubiquitin K-to-R Mutants to identify the required lysine, and Ubiquitin K-Only Mutants to verify linkage specificity [8]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and kits used for studying protein ubiquitination.

| Research Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap [1] | Immunoprecipitation of ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins. | Uses a high-affinity anti-Ubiquitin nanobody (VHH); suitable for pulldowns from mammalian, insect, plant, and yeast extracts; low background; available in agarose and magnetic agarose formats. |

| K48 Ubiquitin Linkage ELISA Kit [9] | Relative and absolute quantitation of K48-linked polyubiquitination. | Enables specific measurement of K48 linkages, the primary signal for proteasomal degradation, in cellular and tissue lysates. |

| Ubiquitin Mutant Panel (e.g., K-to-R, K-Only) [2] [8] | Determining ubiquitin chain linkage and type. | Essential for in vitro assays to distinguish between chain types (e.g., poly- vs. multi-mono-) and to identify the specific lysine residue (K6, K11, K48, K63, etc.) used for chain linkage. |

| Recombinant Enzymes (E1, E2, E3) [2] [8] | Reconstituting the ubiquitination cascade in vitro. | Used for in vitro ubiquitination assays to validate substrates, study enzyme kinetics, and characterize chain topology. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies [6] | Detecting specific polyubiquitin chain linkages by Western blot, IHC, or IP. | Antibodies specifically recognizing M1-, K11-, K48-, K63-linked chains, etc., allow for the study of chain-specific signaling in cells and tissues without genetic manipulation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Distinguishing Poly-ubiquitination from Multi-mono-ubiquitination

This protocol is critical for determining the topology of ubiquitin modification on your protein of interest [2].

Materials:

- Wild-type Ubiquitin

- Ubiquitin No K (a mutant where all 7 lysines are mutated to arginines)

- E1 Enzyme

- Relevant E2 Enzyme

- Relevant E3 Ligase (substrate-specific)

- 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer (500 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM TCEP)

- MgATP Solution (100 mM)

- Your protein substrate

Procedure:

- Set up two 25 µL reactions in parallel:

- Reaction 1: Contains wild-type Ubiquitin.

- Reaction 2: Contains Ubiquitin No K.

- For each reaction, combine the following components in order:

- dH₂O to 25 µL

- 2.5 µL 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer

- 1 µL Ubiquitin (wild-type or No K) (~100 µM final)

- 2.5 µL MgATP Solution (10 mM final)

- Your substrate (5-10 µM final)

- 0.5 µL E1 Enzyme (100 nM final)

- 1 µL E2 Enzyme (1 µM final)

- E3 Ligase (1 µM final)

- Incubate reactions at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Terminate the reactions by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

Interpretation:

- Poly-ubiquitination: High molecular weight (HMW) bands/smears will be visible in Reaction 1 (wild-type Ub) but will be absent or dramatically reduced in Reaction 2 (Ubiquitin No K).

- Multi-mono-ubiquitination: HMW bands/smears will be visible in both Reaction 1 and Reaction 2, as Ubiquitin No K can still be attached to multiple lysines on the substrate, just not to itself.

Protocol: Determining Ubiquitin Chain Linkage

This method uses ubiquitin mutants to identify the specific lysine residue used for polyubiquitin chain assembly [8].

Materials:

- Panel of Ubiquitin K-to-R Mutants (K6R, K11R, K27R, K29R, K33R, K48R, K63R)

- Panel of Ubiquitin K-Only Mutants (K6 Only, K11 Only, etc.)

- Other reagents as in Protocol 4.1.

Procedure - Part A: Identification

- Set up nine separate in vitro ubiquitination reactions: one with wild-type Ub, one with each of the seven Ubiquitin K-to-R Mutants, and one negative control (no ATP).

- Incubate and analyze by Western blot as in Protocol 4.1.

- Interpretation: The reaction containing the K-to-R mutant that is unable to form HMW chains (while all others can) indicates the essential lysine for linkage. For example, if only the K48R mutant reaction lacks HMW smears, the chain is likely K48-linked.

Procedure - Part B: Verification

- Set up nine new reactions: one with wild-type Ub, one with each of the seven Ubiquitin K-Only Mutants, and one negative control.

- Incubate and analyze by Western blot.

- Interpretation: Only the wild-type Ub reaction and the reaction with the "K-Only" mutant corresponding to the identified linkage (e.g., K48 Only) will form HMW chains. This confirms the linkage type.

In ubiquitinated protein enrichment research, non-specific binding presents a significant technical challenge. It refers to the unwanted adsorption of proteins, lipids, or other cellular components to your solid supports during purification, which can obscure genuine results, reduce sensitivity, and lead to false positives. This guide explores the root causes of this interference and provides actionable strategies for achieving cleaner, more reliable enrichments.

FAQ: The Core Principles of Non-Specific Binding

Q1: What is non-specific binding in the context of protein enrichment?

Non-specific binding is a form of adsorption where molecules adhere to solid surfaces via non-covalent interactions, such as electrostatic forces or hydrophobic effects, rather than through a specific, targeted affinity. In ubiquitin pulldown experiments, this means non-ubiquitinated proteins co-purify with your target ubiquitinated proteins, complicating your analysis [10].

Q2: Why is it a particular problem when enriching ubiquitinated proteins?

Ubiquitinated proteins are typically of low abundance within the total cellular proteome. This low stoichiometry means that even a small amount of non-specific binding can overwhelm the signal from your genuine targets. Furthermore, the process is susceptible to interference from endogenously biotinylated proteins or histidine-rich proteins when using specific affinity tags, and the rapid degradation of ubiquitinated substrates by the proteasome adds to the challenge [6] [10] [11].

Q3: What are the three primary factors that determine the extent of non-specific binding?

The occurrence and severity of non-specific binding are governed by an interplay of three core factors [10]:

- The Properties of the Solid Surface: The material of your tubes, columns, and beads.

- The Composition of the Solution: The biological matrix (e.g., cell lysate, plasma) and its components.

- The Physicochemical Nature of the Analytes: The characteristics of the proteins and drugs in your sample.

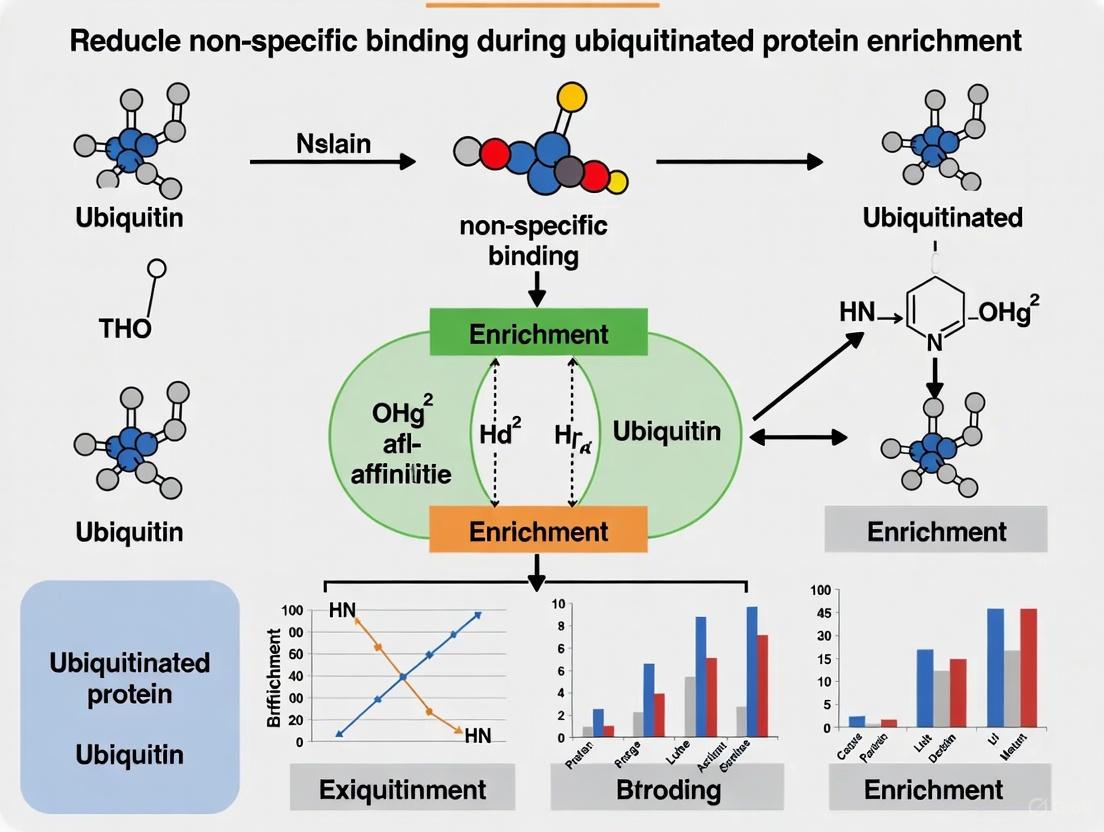

Diagram: The three primary factors contributing to non-specific binding and their interactions.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Common Culprits

The Solid Surface

Different materials used in lab consumables have distinct adsorption principles.

Table 1: Adsorption Principles of Common Material Surfaces

| Contact Surface Type | Primary Adsorption Principle | Common Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Glassware | Ion-exchange, bond-breaking reaction with silica-oxygen [10] | Formulation preparation, sample storage |

| Polypropylene & Polystyrene Consumables | Electrostatic and hydrophobic effects [10] | Sample tubes, 96-well plates |

| Metal Liquid Phase Lines & Columns | Electrostatic effect, metal chelation [10] | HPLC-MS systems |

Actionable Solutions:

- Use low-adsorption tubes and plates specifically designed for proteins and nucleic acids [10].

- For liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis, employ surface-passivated chromatographic columns and liquid phase systems to minimize adsorption of problematic compounds like phosphorylated or nucleic acid drugs [10].

The Solution Composition & Biological Matrix

The complexity of your biological sample is a major determinant of interference.

Table 2: Matrix-Specific Interference and Desorption Strategies

| Matrix Type | Interference Profile | Recommended Desorption Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma/Serum | Weaker adsorption due to plasma proteins and lipids that can attenuate analyte binding. However, small molecule drugs may bind to plasma proteins [10]. | Addition of competing agents like bovine serum albumin (BSA) [10]. |

| Urine, Bile, Cerebrospinal Fluid | High potential for interference due to lower concentrations of proteins and lipids that would otherwise block binding sites [10]. | Add organic reagents to increase analyte solubility; use surfactants to improve dispersion [10]. |

| Whole Cell Lysates | Highly complex; contains all cellular components. A major source of "bead-binding" proteins that appear in both test and control samples [12]. | Use optimized bead-based blacklists to identify common contaminants; increase stringency of wash buffers [12]. |

The Analyte and "Beacon" Proteins

Certain molecules are inherently "sticky," and some proteins are notorious for appearing in enrichments regardless of the bait.

Inherently Sticky Molecules:

- Peptides, Proteins, and Peptide-Drug Conjugates (PDCs): These often have amphoteric properties (both positively and negatively charged groups), leading to strong electrostatic interactions. Large structures also exhibit pronounced hydrophobic effects [10].

- Nucleic Acid Drugs: Phosphate groups can chelate metal ions and bind to metal surfaces [10].

- Cationic Lipids: Possess a positively charged head group (electrostatic effect) and a long hydrophobic tail, making them highly prone to adsorption [10].

Common Protein Culprits in Affinity Purifications: Research has identified a "bead proteome"—a blacklist of proteins that frequently bind nonspecifically to common affinity matrices like magnetic, sepharose, and agarose beads [12]. While these proteins can be genuine interactors in other contexts, their consistent appearance at similar levels in both test and control samples flags them as frequent gatecrashers. You should not automatically discount a protein on this list, but it should prompt rigorous validation [12].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol 1: TUBE-Based Purification of Ubiquitinated Proteins

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) are engineered reagents with very high affinity for polyubiquitin chains, offering protection from deubiquitinases (DUBs) and the proteasome [11].

Workflow:

- Harvest and Lyse: Snap-freeze tissue or cells in liquid nitrogen. Lyse in a suitable buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) supplemented with 1% IGEPAL detergent, protease inhibitors, and DUB inhibitors (e.g., PR-619) [11].

- Clarify: Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., 70,000 x g for 30 min) to remove insoluble debris [13].

- Incubate with TUBE Resin: Incubate the clarified supernatant with TUBE-conjugated agarose resin for 30 minutes at 4°C under rotation [13] [11].

- Wash: Wash the beads thoroughly with lysis buffer followed by a wash buffer (e.g., 50 mM NH₄HCO₃) to remove non-specifically bound proteins [13].

- Elute: Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer for downstream analysis by immunoblotting or mass spectrometry [13].

Diagram: Key steps in the TUBE-based purification workflow for ubiquitinated proteins.

Protocol 2: Addressing Analyte Adsorption

For problematic molecules like peptides or nucleic acids, modify the solution conditions.

- Investigate Adsorption: Use continuous transfer or gradient dilution experiments. Compare signal differences when the same volume of solution is placed in containers of different sizes to assess surface area-dependent loss [10].

- Add Desorption Agents:

- Surfactants: Agents like Tween or CHAPS can uniformly disperse analytes, weakening hydrophobic effects. Note: They can cause signal suppression in MS, so selection is key [10].

- Competitive Blockers: Add BSA or purified plasma to compete for non-specific binding sites on consumables [10].

- Chelators: For nucleic acid drugs, add EDTA to the mobile phase to chelate metal ions and reduce adsorption to metal pipelines and columns [10].

- Optimize Solvent: Screen different solvent types and adjust the pH to improve the solubility of the compound, thereby reducing its tendency to adsorb to surfaces [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitin Enrichment and NSB Mitigation

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | High-affinity enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins; protects from DUBs and proteasomal degradation [13] [11]. | Available as pan-specific or linkage-specific (e.g., for K48 or K63 chains). |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of ubiquitinated proteins with specific chain linkages (e.g., K48, K63) [6] [14]. | High cost; potential for non-specific antibody binding itself. |

| Tagged Ubiquitin (e.g., His, Strep) | Expression in cells allows enrichment of ubiquitinated conjugates via affinity resins (Ni-NTA, Strep-Tactin) [6]. | May not mimic endogenous ubiquitin; cannot be used in human tissue samples. |

| DiGly Remnant Antibodies | Enrichs tryptic peptides with diGly lysine remnants for MS-based ubiquitinome mapping [15] [11]. | Cannot distinguish between ubiquitin, NEDD8, and ISG15 modifications [13]. |

| Low-Adsorption Consumables | Tubes and plates with surface passivation to minimize binding of sticky molecules like proteins and nucleic acids [10]. | Essential for working with low-abundance analytes or "sticky" molecules like cationic lipids. |

| DUB Inhibitors (e.g., PR-619) | Added to lysis buffers to prevent the cleavage of ubiquitin from substrates during processing, preserving the ubiquitinome [11]. | Critical for maintaining the integrity of your target signal. |

FAQ: Understanding Non-Specific Binding in Ubiquitin Enrichment

What is non-specific binding and why is it a critical issue in ubiquitylomic studies?

Non-specific binding (NSB) refers to the adsorption of analytes (like proteins or antibodies) to unintended surfaces or molecules via non-covalent interactions, rather than through the desired specific, affinity-based binding [16] [10]. In the context of ubiquitinated protein enrichment for mass spectrometry (MS), this means that non-ubiquitinated proteins or other biomolecules can co-purify, contaminating your sample.

This is critical because MS analysis of these contaminated samples leads to:

- Compromised Sensitivity: The signals from genuine, often low-abundance ubiquitinated peptides are obscured by the high background noise from non-specifically bound proteins, making them harder to detect [17].

- Reduced Specificity: It becomes difficult to distinguish true ubiquitination events from background, resulting in false-positive identifications and unreliable data on the ubiquitin code [18].

How does non-specific binding directly impact my mass spectrometry results?

NSB introduces analytical errors that propagate through your MS workflow, primarily affecting data quality and accuracy:

- Skewed Quantification: Non-specific adsorption can lead to inconsistent sample recovery, causing higher signal intensity at high analyte concentrations and lower intensity at low concentrations. This non-linearity compromises the accuracy of quantitative measurements [10].

- Poor Chromatographic Performance: Adsorption to system components can cause peak tailing, system carryover, and distorted chromatographic peaks, reducing the resolution and quality of MS data [10].

- Masking of Low-Abundance Peptides: The complexity introduced by non-specifically bound proteins can overwhelm the MS detection system, suppressing the signal of true, low-abundance ubiquitinated peptides and reducing the depth of your ubiquitylome analysis [18] [17].

What are the primary factors that contribute to non-specific binding?

The occurrence and severity of NSB are governed by three main factors, as detailed in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Key Factors Contributing to Non-Specific Binding

| Factor | Description | Common Examples in Sample Prep & MS |

|---|---|---|

| Properties of the Solid Surface [10] | The material and chemical properties of the surfaces the sample contacts. | Glass (ion-exchange), polypropylene plastics (hydrophobic effect), and metal liquid chromatography lines/columns (electrostatic effect). |

| Composition of the Solution [10] | The chemical matrix in which the analyte is dissolved. | Simple solvents (water, organic buffers) show higher NSB potential. Complex matrices like plasma can reduce NSB due to blocking by proteins and lipids. |

| Properties of the Analytic [10] | The inherent physicochemical characteristics of the molecule being studied. | Peptides, proteins, and nucleic acids are prone to NSB due to amphoteric nature. Cationic lipids and phosphorylated compounds also show strong electrostatic/hydrophobic effects. |

What types of molecules are most prone to causing non-specific binding?

Certain molecule classes are particularly problematic due to their structural properties:

- Peptides, Proteins, and Peptide-Drug Conjugates (PDCs): These contain amino acids with charged groups (e.g., lysine, arginine), leading to strong electrostatic interactions. Their large size also contributes to hydrophobic effects [10].

- Nucleic Acids: These are amphoteric molecules where phosphate groups can bind to metal surfaces, and bases contain amino groups that participate in non-specific interactions [10].

- Cationic Lipids: Molecules like DOTAP possess a positively charged head group (electrostatic effect) and a long hydrophobic tail, making them highly susceptible to NSB [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Strategies for Reducing NSB in Ubiquitin Enrichment

The following diagram illustrates the dual-pathway impact of Non-Specific Binding (NSB) on Mass Spectrometry results and the primary strategies to mitigate it, focusing on the enrichment process and the analytical system.

Strategy 1: Optimize Buffer Composition and Use Blocking Agents

The careful formulation of your buffers is one of the most effective ways to minimize NSB.

- Use Blocking Agents: Incorporate agents like bovine serum albumin (BSA), casein, fish gelatin, or commercial protein stabilizers (e.g., StabilGuard) to occupy remaining active sites on surfaces (e.g., beads, tubes) after immobilization of your capture antibody [16] [19].

- Add Surfactants: Low concentrations (e.g., 0.1%) of non-ionic detergents like Tween-20, Triton X-100, or NP-40 can disrupt hydrophobic interactions that cause NSB [20] [21] [10].

- Adjust Ionic Strength: Supplementing your lysis and wash buffers with 150-300 mM NaCl can shield electrostatic interactions [19]. For more stringent washing, concentrations up to 500 mM may be used [19].

- Control pH and Additives: Adjusting the pH of your solvent can improve analyte solubility and reduce NSB [10]. For nucleic acids or phosphorylated compounds, adding chelating agents like EDTA to the mobile phase can reduce metal-ion-mediated adsorption to LC systems [10].

Strategy 2: Implement Rigorous Surface Passivation

Minimize contact between your precious sample and reactive surfaces throughout the workflow.

- Use Low-Binding Consumables: Always use low-protein-binding tubes and plates for storing and processing samples, especially for sensitive molecules like proteins and nucleic acids [10].

- Pre-Block Magnetic/Agarose Beads: Before incubating with your sample, pre-treat beads with 1-5% BSA or other unrelated proteins to block hydrophobic adsorption sites [19].

- Employ Low-Adsorption LC Systems: For the final MS analysis, use liquid chromatography systems with passivated (inert) metal fluid paths and columns designed to minimize adsorption. This is particularly crucial for analyzing challenging molecules like phosphorylated peptides and nucleic acids, as it significantly improves peak shape and signal intensity [10].

Strategy 3: Apply Mathematical Correction to MS Data

For advanced troubleshooting, computational methods can help deconvolute specific from non-specific signals post-acquisition. A mathematical model has been developed to correct for NSB in binding data, such as that from native MS or other single-molecule methods [22] [23].

- Principle: The method assumes a known number of specific binding sites and that nonspecific binding is non-cooperative. It uses the ratio of intensities from peaks with ligand numbers exceeding the known specific sites to calculate a nonspecific binding constant (Kn) [22].

- Application: This constant is then used to subtract the artificial intensity increases due to NSB from all peaks, revealing the true distribution of specific binding stoichiometries [22]. This approach was successfully demonstrated for ADP binding to creatine kinase using MS data [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Minimizing Non-Specific Binding

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| BSA, Casein, or Commercial Blockers (e.g., StabilGuard) [16] [19] | Blocks residual binding sites on surfaces (beads, tubes, plates) to prevent non-specific adsorption. | Pre-blocking magnetic beads before immunoprecipitation. |

| Non-Ionic Detergents (e.g., Tween-20, Triton X-100, NP-40) [21] [19] [10] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions by acting as a surfactant. | Adding 0.1% to lysis and wash buffers during ubiquitinated protein enrichment. |

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Kit [17] | Provides optimized, immobilized affinity reagents (e.g., agarose with ubiquitin-binding antibodies) for specific pull-down. | Isolating polyubiquitinated proteins from complex cell lysates prior to MS. |

| Phosphoprotein Enrichment Kit [17] | Uses metal chelate affinity (e.g., IMAC) to bind phosphate groups, a common approach also reflective of strategies for other PTMs. | A related example for enriching phosphorylated proteins; demonstrates the use of specialized kits to reduce background. |

| Low-Adsorption Tubes & Plates [10] | Consumables with specially treated polymer surfaces to minimize analyte binding. | Storing and processing peptide samples, urine, bile, or CSF. |

| Low-Adsorption LC Columns & Systems [10] | Chromatography components with passivated metal surfaces to prevent adsorption of analytes. | LC-MS analysis of phosphopeptides, nucleic acids, or cationic lipids to improve peak shape and recovery. |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) [10] | A chelating agent that binds metal ions, reducing metal-ion-mediated adsorption in the LC system. | Adding to the mobile phase when analyzing nucleic acids or other metal-sensitive compounds. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the most critical first step in planning an enrichment experiment for ubiquitinated proteins? The most critical step is to precisely define your experimental goal. You must determine whether you need to identify novel ubiquitin-binding proteins, characterize the ubiquitin chain architecture (linkage type and length), or profile global ubiquitination sites on substrates. This goal dictates the choice between affinity enrichment mass spectrometry (AE-MS), linkage-specific tools, or ubiquitinated peptide enrichment [24] [25].

FAQ 2: My enrichment yields high background noise. What are the primary strategies to reduce non-specific binding? High background often stems from non-specific protein interactions with the solid support or the affinity tag. To mitigate this:

- Use control resins immobilized with a non-functional mutant tag or an irrelevant antibody.

- Optimize wash buffer stringency by including low concentrations of detergents or moderately increasing salt concentration to disrupt weak, non-specific interactions without eluting your target [26].

- Employ tandem-repeated Ub-binding entities (TUBEs) instead of single UBDs, as they offer higher affinity for ubiquitinated proteins, allowing for more stringent wash conditions that reduce background [25].

FAQ 3: How can I prevent the hydrolysis of native ubiquitin chains by deubiquitinases (DUBs) during cell lysis and enrichment? The use of non-hydrolyzable ubiquitin variants is a key strategy. Chemical biology tools can generate ubiquitin chains linked via triazole bonds or isopeptide-N-ethylated bonds, which mimic native linkages but are resistant to DUB activity. Including DUB inhibitors in all lysis and wash buffers is also essential when working with native ubiquitin [24].

FAQ 4: What enrichment method should I use if I need to work with clinical tissue samples where genetic tagging is not possible? For clinical samples, antibody-based enrichment is the most suitable method. Antibodies like P4D1, FK1, or FK2 can recognize endogenous ubiquitinated proteins without the need for prior genetic manipulation. Linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., for K48 or K63 chains) can also be used to gain insights into chain architecture directly from tissue lysates [25].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Low Yield of Target Ubiquitinated Proteins

- Potential Cause 1: Inefficient elution conditions.

- Solution: Test a panel of elution buffers. Start with 0.1 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.5-3.0) and immediately neutralize with Tris buffer. If this denatures your protein, try higher salt concentrations (e.g., 3.5 M MgCl₂) or specific competitors [26].

- Potential Cause 2: Instability of the ubiquitin-protein conjugate.

- Solution: Ensure DUB inhibitors are present throughout the process. Consider switching to non-hydrolyzable ubiquitin variants for interaction studies [24].

Problem: High Levels of Non-Specific Binding

- Potential Cause 1: The solid support or affinity tag is attracting unrelated proteins.

- Solution: Pre-clear the cell lysate by incubating it with the underivatized support (e.g., bare agarose resin). If using tagged ubiquitin, be aware that proteins binding to the tag (e.g., histidine-rich proteins with His-tags) can be common contaminants [25].

- Potential Cause 2: Wash conditions are too mild.

- Solution: Incorporate a wash step with a buffer containing 0.1-0.5% detergent or 500 mM NaCl to disrupt ionic and hydrophobic interactions without affecting specific ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD) interactions [26].

Comparison of Ubiquitin Enrichment Methodologies

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major enrichment strategies to help you select the best approach for your research question.

| Methodology | Key Principle | Ideal Application | Throughput | Key Advantages | Key Limitations/Liability to Non-Specific Binding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ub Tagging (e.g., His/Strep) [25] | Expression of affinity-tagged Ub in cells; enrichment of conjugated substrates. | Identifying novel ubiquitination substrates in cultured cells. | High | Relatively easy and low-cost; good for screening. | Co-purification of proteins that bind to the tag (e.g., histidine-rich proteins); cannot be used on tissues. |

| Antibody-Based [25] | Immunoaffinity purification using anti-ubiquitin antibodies. | Profiling endogenous ubiquitination in any sample, including clinical tissues. | Medium | Works on endogenous proteins; linkage-specific antibodies available. | High cost; potential for non-specific antibody binding; epitope masking. |

| UBD-Based (e.g., TUBEs) [25] | Enrichment using recombinant proteins with high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domains. | Gentle purification of labile ubiquitin conjugates for functional analysis. | Medium | Protects ubiquitin chains from DUBs and proteasomal degradation; high affinity. | Requires production of recombinant protein; some UBDs may have linkage preferences. |

| Chemical Biology (AE-MS) [24] | In vitro synthesis of defined Ub variants (e.g., triazole-linked chains) as bait for interactors. | Mapping the interactome of specific ubiquitin chain types and lengths. | High | Unprecedented control over Ub chain topology; resistance to DUB hydrolysis. | Requires expertise in synthetic biology/chemistry; may not fully replicate native isopeptide bond. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Enrichment Strategies

Protocol 1: Affinity Enrichment-Mass Spectrometry (AE-MS) with Defined Ubiquitin Variants

This protocol uses chemically synthesized ubiquitin chains to identify specific interacting proteins [24].

Generation of Defined Ub Variants:

- Synthesis: Generate diubiquitin or ubiquitin chains of defined linkage using click chemistry. For example, incorporate an azido-ornithine at the desired lysine position in the proximal Ub and a propargylamine at the C-terminus of the distal Ub. Perform copper(I)-catalyzed alkyne-azide cycloaddition (CuAAC) to form a triazole-linked chain [24].

- Immobilization: Couple the synthesized ubiquitin variant to a solid-phase support like beaded agarose resin to create the affinity matrix [26].

Affinity Enrichment from Cell Lysate:

- Incubation: Incubate the ubiquitin-conjugated resin with a pre-cleared crude cell lysate for a defined period (e.g., 1-2 hours) under near-physiological conditions (e.g., using PBS buffer) to allow protein interactions to occur [24] [26].

- Washing: Wash the resin extensively with binding buffer. To reduce non-specific binding, include low levels of detergent or a moderate salt concentration (e.g., 150-500 mM NaCl) in the wash buffer [26].

- Elution: Elute the bound proteins using an appropriate elution buffer. Common choices include 0.1 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.5-3.0) or Laemmli buffer for direct analysis by SDS-PAGE [26].

Identification by Mass Spectrometry:

- Resolve the eluted fractions by SDS-PAGE.

- Analyze the protein bands by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Identify interacting proteins using label-free quantification or other proteomic methods [24].

Protocol 2: Tandem Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Peptides (SCASP-PTM)

This protocol allows for the sequential enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides from a single sample digest for mass spectrometry analysis [27].

Protein Extraction and Digestion:

- Extract proteins using the SDS-cyclodextrin-assisted sample preparation (SCASP) method.

- Digest the extracted proteins with trypsin to create a peptide mixture.

Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Peptides:

- Without an intermediate desalting step, subject the peptide digest to enrichment for ubiquitinated peptides. This typically uses anti-di-glycine remnant antibodies that recognize the signature Gly-Gly modification left on lysines after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins.

- Retain the flow-through from this step for subsequent enrichment of other PTMs.

Clean-up and Analysis:

- Desalt the enriched ubiquitinated peptides.

- Analyze by data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem-repeated Ub-binding Entities (TUBEs) [25] | High-affinity enrichment of endogenous ubiquitinated proteins; protects chains from DUBs. | Superior to single UBDs for reducing background and stabilizing conjugates. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies [25] | Immunoaffinity purification of ubiquitin chains with a specific linkage (e.g., K48, K63). | Essential for studying the biology of distinct ubiquitin signals in tissues. |

| Non-hydrolyzable Ub Variants (Triazole-linked) [24] | Serves as DUB-resistant bait in AE-MS to identify linkage-specific interactors. | Mimics native ubiquitin structure while providing experimental stability. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Added to lysis and enrichment buffers to preserve native ubiquitin conjugates. | Critical for maintaining the integrity of the ubiquitinome during processing. |

| Crosslinked Beaded Agarose (e.g., CL-4B) [26] | A common, porous solid support for immobilizing antibodies, TUBEs, or ubiquitin variants. | Provides high surface area, low non-specific binding, and good flow characteristics. |

| Elution Buffers (Glycine, Chaotropes) [26] | Dissociates bound targets from the affinity matrix for recovery. | Choice impacts protein stability; harsh (low pH) vs. gentle (competitor) elution must be tested. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the core decision-making workflow for selecting an appropriate ubiquitin enrichment strategy based on your primary experimental goal.

Diagram 1: A workflow to guide the selection of a ubiquitin enrichment strategy based on the researcher's primary goal and experimental constraints.

Robust Enrichment Methodologies and Protocols to Minimize Non-Specific Interactions

Affinity tags are indispensable tools in modern molecular biology, facilitating the purification and detection of recombinant proteins. These peptide sequences, grafted onto a protein of interest, allow for selective enrichment from complex mixtures like cell lysates using specific immobilized ligands [28]. While immensely powerful, a significant challenge inherent to these methods is co-purification, where non-target proteins or contaminants are isolated alongside the protein of interest. This non-specific binding undermines purity and can complicate downstream analysis and experimental interpretations. This guide addresses common issues, particularly within the context of ubiquitinated protein research, providing troubleshooting strategies to enhance the specificity of your affinity enrichments.

Comparing Common Affinity Tags

The choice of affinity tag profoundly influences the success of purification, impacting yield, purity, and the degree of co-purification. Each tag presents a unique balance of advantages and inherent challenges.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Common Affinity Tags

| Tag | Typical Size | Binding Ligand | Key Advantages | Common Co-purification Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexahistidine (His-tag) | 6 aa (0.84 kDa) [28] | Metal ions (Ni²⁺, Co²⁺) [28] | Small size; high capacity; mild elution with imidazole [28] [29] | Binding of host proteins with histidine clusters or metal-binding sites [29]. |

| Strep-tag II | 8 aa (1.06 kDa) [28] | Strep-Tactin (engineered streptavidin) [28] | High specificity; elution under physiological conditions with desthiobiotin [30] [31] | Co-purification of endogenously biotinylated proteins [6]. |

| GST | 211 aa (26 kDa) [28] | Glutathione [28] | Can enhance solubility of fusion partners [28] [29] | The tag can dimerize, leading to complex formation; slow binding kinetics [29]. |

| FLAG | 8 aa (1.01 kDa) [28] | Anti-FLAG antibody [28] | High specificity; hydrophilic, minimizing impact on protein function [29] | Low binding capacity can limit yield; requires gentle elution conditions [29]. |

The following diagram illustrates the general decision-making workflow for selecting an affinity tag to minimize co-purification, based on key experimental goals.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Common Problems

No or Low Protein Yield in Eluate

Problem: After completing the purification protocol, little to no target protein is found in the elution fraction.

Potential Cause 1: Expression or Tag Accessibility Issue.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Construct: Sequence your DNA construct to ensure no cloning errors and that the affinity tag is in the correct frame with the protein of interest [32].

- Check Expression: Run a small sample of your crude lysate on an SDS-PAGE gel and perform a western blot using an antibody against your affinity tag to confirm expression [32].

- Improve Tag Accessibility: If the tag is buried or inaccessible, consider purifying under denaturing conditions (e.g., with 6-8 M urea) to expose the tag, provided your protein and downstream applications allow it [32].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Potential Cause 2: Inefficient Elution Conditions.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Optimize Elution Buffer: Test a gradient of elution buffer strengths. For a His-tag, test increasing concentrations of imidazole (e.g., 50-500 mM). For a Strep-tag, ensure fresh desthiobiotin is used [29] [30].

- Use Alternative Eluents: If mild conditions fail, try specific or harsher elution buffers compatible with your tag, such as low pH (0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.5-3.0) or high salt, followed by immediate buffer exchange [28] [26].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

High Background of Non-Specific Binding (Co-purification)

Problem: The final eluate contains a high concentration of non-target proteins, reducing the purity of your sample.

Potential Cause 1: Insufficiently Stringent Wash Conditions.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Optimize Wash Buffer: Introduce mild detergents (e.g., 0.01-0.1% Tween-20) or low concentrations of imidazole (10-20 mM for His-tags) into the wash buffer to disrupt weak, non-specific interactions without eluting your target [29] [32].

- Increase Wash Volume and Number: Perform multiple wash steps with an adequate volume of optimized wash buffer to ensure thorough removal of contaminants.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Potential Cause 2: Inherent Properties of the Tag or Resin.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- His-tag Specific: For purifications from mammalian cell lysates, be aware that endogenous histidine-rich proteins can bind. Increasing imidazole in the wash buffer is critical [29].

- Strep-tag Specific: Endogenously biotinylated proteins (e.g., carboxylases) may co-purify. Using Strep-Tactin instead of streptavidin and stringent washes can mitigate this [6].

- Use a Control Bead: Whenever possible, perform a parallel purification with control beads (e.g., resin without ligand or with a mutated binding protein) to identify proteins that bind non-specifically to the resin itself [33].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Target Protein Elutes in Wash Steps

Problem: Your target protein is not retained on the resin and is found in the flow-through or wash fractions.

- Potential Cause: Weak Binding or Overloading.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Binding Capacity: Ensure you are not exceeding the binding capacity of the resin. Use less lysate or more resin.

- Modify Binding Conditions: Optimize the binding buffer's pH and ionic strength to create ideal conditions for the tag-ligand interaction. Avoid harsh salts or detergents during binding.

- Reduce Wash Stringency: If the protein is eluting during washes, the wash buffer may be too strong. Reduce the concentration of imidazole, detergent, or salt in the wash buffer [32].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Special Considerations for Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment

Enriching ubiquitinated proteins presents unique challenges due to the low stoichiometry of modification and the complexity of ubiquitin chains. Specific methodologies have been developed to address these challenges, primarily falling into three categories.

Table 2: Methods for Enriching Ubiquitinated Proteins

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Challenges & Co-purification Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Tagging | Expression of affinity-tagged Ub (e.g., His-, Strep-) in cells. Tag is covalently attached to substrates [6]. | Easy, high-throughput, and relatively low-cost [6]. | Tagged Ub may not fully mimic endogenous Ub; co-purification of histidine-rich or biotinylated host proteins [6]. |

| Antibody-Based | Use of anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK2) or linkage-specific antibodies to enrich modified proteins [6]. | Enables study of endogenous ubiquitination; linkage-specific antibodies provide chain architecture data [6]. | High cost; potential for non-specific antibody binding [6]. |

| UBD-Based (e.g., TUBEs) | Use of Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs), proteins with high-affinity for poly-Ub chains, for enrichment [34]. | Protects ubiquitin chains from deubiquitinases (DUBs) and proteasomal degradation; can be linkage-specific [34]. | Requires careful use of mutated TUBE controls (e.g., CUB02-beads) to distinguish specific binding [34] [33]. |

The experimental workflow for TUBE-based enrichment, a powerful method to reduce co-purification of non-ubiquitinated proteins, is outlined below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: For ubiquitination studies, should I use a tagged ubiquitin approach or an antibody/TUBE-based approach? The best choice depends on your experimental goals. Tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His-Ub) is excellent for discovering novel ubiquitination substrates and sites in a high-throughput manner [6]. In contrast, antibody- or TUBE-based approaches are essential for studying endogenous ubiquitination without genetic manipulation, making them suitable for clinical samples or animal tissues [6] [34].

Q2: My Strep-tag purification has low yield. What could be wrong? First, ensure you are using the correct ligand, Strep-Tactin, which has higher affinity for the Strep-tag II than native streptavidin [30] [31]. Second, verify you are eluting with a competitive ligand like desthiobiotin, which allows for gentle and efficient elution under physiological conditions. Using insufficient desthiobiotin or outdated reagent are common causes of low yield [30].

Q3: How can I definitively prove that a protein I've purified is specifically bound and not a co-purifying contaminant? The most robust method is to include the appropriate control resin. This involves running a parallel purification with beads that lack the specific ligand (e.g., empty resin) or contain a ligand with a mutated binding site (e.g., CUB02 beads for TUBE experiments) [33]. Any proteins present in your experimental eluate but absent in the control eluate are specific binders.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Affinity-Based Purification

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Strep-Tactin Resin | An engineered streptavidin with high affinity for Strep-tag II, allowing purification under physiological conditions [30] [31]. | Purification of Strep-tagged fusion proteins or biotinylated interactors in BioID experiments [31]. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Engineered proteins with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains, used to enrich ubiquitinated proteins while protecting them from deubiquitinases [34]. | Enrichment of endogenous polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates for proteomic analysis or western blotting [34]. |

| Control Beads (e.g., CUB02) | Beads conjugated to a mutated version of the binding protein (e.g., TUBE) that cannot bind the target, serving as a critical negative control [33]. | Differentiating specific enrichment from non-specific background binding in ubiquitination pull-down assays [33]. |

| Desthiobiotin | A biotin analog with reduced affinity for Strep-Tactin/streptavidin, used for gentle, competitive elution of Strep-tagged proteins [30]. | Eluting functional, Strep-tagged proteins from Strep-Tactin resin without denaturation [30]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Reagent Selection

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between pan-specific and linkage-specific anti-ubiquitin antibodies?

- Pan-specific antibodies recognize a common epitope on ubiquitin, allowing them to detect and enrich all ubiquitinated proteins regardless of the chain linkage type. They are useful for global profiling of the "ubiquitylome" [35] [36].

- Linkage-specific antibodies are engineered to recognize a unique structural epitope formed when ubiquitin molecules are linked through a specific lysine residue (e.g., K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1). They are essential for deciphering the "ubiquitin code," as different linkage types dictate distinct cellular outcomes for the modified protein, such as proteasomal degradation (K48-linked) or kinase activation in immune signaling pathways (K63-linked) [37] [36].

Q2: When should I use a pan-specific versus a linkage-specific antibody for enrichment?

Your choice depends on the research question:

- Use pan-specific antibodies when your goal is to identify novel ubiquitination substrates or perform global ubiquitin profiling without a priori knowledge of the linkage involved [6] [35].

- Use linkage-specific antibodies when you are investigating a specific biological process known to be mediated by a particular ubiquitin chain type. For example, use K63-linkage-specific antibodies to study innate immune signaling pathway activation, or K48-linkage-specific antibodies to investigate proteasomal targeting [37] [36].

Q3: What are the primary causes of non-specific binding during antibody-based enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins?

Non-specific binding can arise from several sources:

- Antibody Cross-reactivity: The antibody may have affinity for non-target epitopes on other proteins or for non-target ubiquitin linkages [38] [36].

- Endogenous Biotin: If using a biotin-streptavidin based detection system, high levels of endogenous biotin in tissues like liver and kidney can cause high background [39] [40].

- Protein-Protein Interactions: Non-ubiquitinated proteins can bind nonspecifically to the solid support (e.g., resin/beads) or to the antibody itself [6] [41].

- Insufficient Blocking: Failure to adequately block the solid support or the tissue sample prior to antibody incubation can lead to nonspecific antibody binding [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting High Background and Non-Specific Binding

| Problem & Symptoms | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background across entire sample | Inadequate blocking of membrane or resin. | Increase concentration of blocking agent (e.g., BSA, normal serum) or extend blocking time [40]. |

| Endogenous enzyme activity (e.g., peroxidases). | Quench activity with 3% H2O2 in methanol (for peroxidases) or levamisole (for phosphatases) prior to primary antibody incubation [39]. | |

| Primary antibody concentration is too high. | Titrate the antibody to find the optimal dilution that maximizes signal-to-noise [39] [40]. | |

| Specific non-ubiquitin proteins co-enrich | Non-specific protein binding to enrichment resin. | Include control IgG in your experiment. Increase stringency of wash buffers (e.g., add 0.15-0.6 M NaCl, detergents like Tween-20) [39] [41]. |

| Endogenous biotin interference (in biotin-based systems). | Use a polymer-based detection system instead or perform an endogenous biotin block step [39] [40]. | |

| Unexpected or multiple bands in Western blot | Antibody recognizes non-target ubiquitin linkages or non-ubiquitin proteins. | Validate antibody specificity using cell lines with knocked-down target protein or known positive/negative controls for linkage types [38]. |

| Protein degradation in lysate. | Ensure samples are kept on ice and use fresh protease inhibitors during lysate preparation [38]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Signal and Poor Enrichment Efficiency

| Problem & Symptoms | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or no signal despite target presence | Epitope masking in cross-linked tissues. | Optimize antigen retrieval method for IHC (e.g., use microwave heating instead of water bath, test different retrieval buffers) [40]. |

| Low stoichiometry of ubiquitination. | Enrich ubiquitinated proteins from larger amounts of starting lysate (≥1 mg). Use higher-capacity enrichment resins [6]. | |

| Antibody has lost affinity due to degradation or improper storage. | Aliquot antibodies to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. Validate antibody on a known positive control sample [38] [40]. | |

| Inconsistent results with polyclonal antibodies | Lot-to-lot variability from immunized host animals. | Validate each new antibody lot before use. Consider switching to a monoclonal antibody for better reproducibility [38]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitin Enrichment and Detection

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Mechanism | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Pan-specific Ub Antibodies (e.g., clone VU-1) | Enrich and detect mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins of all linkage types by recognizing a common ubiquitin epitope [35]. | Ideal for initial, global surveys of ubiquitination. May be less informative for deducing specific protein fates. |

| Linkage-specific Ub Antibodies (e.g., α-K48, α-K63) | Selectively enrich and detect proteins modified with a specific ubiquitin chain linkage, enabling functional studies of the ubiquitin code [37] [36]. | Critical for probing specific pathways. Requires rigorous validation to confirm linkage specificity and avoid cross-reactivity [36]. |

| Tandem Hybrid UBDs (ThUBDs) | Engineered recombinant proteins with multiple ubiquitin-binding domains that offer high affinity and specificity for polyubiquitin chains, serving as an alternative to antibodies for enrichment [41]. | Can provide superior specificity and lower non-specific binding compared to some antibodies. Requires recombinant protein production. |

| Polymer-based Detection Reagents | Used in IHC/Western blotting for signal amplification; do not contain biotin, thus avoiding background from endogenous biotin [40]. | Highly recommended for tissues with high endogenous biotin (e.g., liver, kidney). Generally offer enhanced sensitivity over biotin-based systems. |

| DUBs (Catalytically Inactive) | Act as linkage-specific affinity reagents by binding tightly but not cleaving specific ubiquitin chain types, useful for enrichment and structural studies [36]. | A powerful tool in the molecular toolbox for linkage-specific analysis, though their use is more specialized [36]. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Ubiquitin Antibody Enrichment Workflow

FAQs: Utilizing OtUBD for Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment

1. How does OtUBD achieve higher specificity for both mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins compared to other affinity reagents like TUBEs?

OtUBD is a single, high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain derived from the Orientia tsutsugamushi bacterium. Its key advantage lies in its exceptionally strong, intrinsic affinity for ubiquitin, with a dissociation constant (Kd) for monoubiquitin in the low nanomolar range (approximately 5 nM) [42]. This inherent high affinity means it does not require a tandem multimerized structure to achieve strong binding.

Unlike Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs), which rely on avidity effects from multiple low-affinity domains and thus show a strong preference for polyubiquitin chains, OtUBD's single-domain high affinity allows it to efficiently capture both monoubiquitinated and polyubiquitinated proteins with high specificity [43] [25]. This is crucial because monoubiquitinated proteins can constitute over 50% of the ubiquitinated proteome in some mammalian cell types [43].

2. What are the critical steps in the OtUBD protocol to minimize non-specific binding and distinguish covalently ubiquitinated proteins from mere interactors?

The primary strategy involves using two different buffer conditions to separate the "ubiquitylome" (covalently ubiquitinated proteins) from the "ubiquitin interactome" (proteins that non-covalently associate with ubiquitin or ubiquitinated proteins) [44] [43].

- For the Ubiquitylome (Covalently Modified Proteins): Use a denaturing lysis and binding buffer (e.g., containing 4-6 M Urea). Denaturing conditions disrupt non-covalent protein-protein interactions, ensuring that only proteins directly conjugated to ubiquitin are purified with the OtUBD resin [44] [45].

- For the Ubiquitin Interactome (Non-covalent Interactors): Use a native (non-denaturing) lysis and binding buffer. This allows the OtUBD resin to co-purify both ubiquitinated proteins and any proteins that stably interact with them or with free ubiquitin [44] [46].

A critical step in both workflows is the inclusion of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) in the lysis buffer. NEM is a cysteine alkylating agent that inhibits deubiquitinases (DUBs), preventing the cleavage and loss of ubiquitin chains from your substrates during lysate preparation [45].

3. My OtUBD pulldown experiments show high background. What are the primary causes and potential solutions?

High background is often related to resin preparation or lysate quality. The table below summarizes common issues and verified solutions based on the established protocol.

Table: Troubleshooting High Background in OtUBD Pulldown Experiments

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Resin Preparation | Incomplete quenching of coupling resin | After coupling OtUBD to the SulfoLink resin, ensure thorough quenching with L-cysteine to block any remaining reactive groups [45]. |

| Resin Preparation | Non-specific interaction with the resin matrix | Include a control with resin coupled to an irrelevant protein or a blank (quenched) resin to identify background from the matrix itself [43]. |

| Lysate Quality | Non-specific protein aggregation | Centrifuge lysates at high speed (e.g., 20,000 x g) before incubation with the resin to remove insoluble debris. Use a sufficient concentration of detergent (e.g., 0.1-1% Triton X-100) in native buffers [45]. |

| Binding & Wash Stringency | Insufficient washing | Increase the number of wash steps or the stringency of wash buffers. For native purifications, increase the salt concentration (e.g., 300-500 mM NaCl) in the wash buffer to reduce electrostatic non-specific binding [44] [45]. |

4. Can the OtUBD method be used to profile ubiquitination in complex tissues, such as patient samples?

A key advantage of OtUBD over methods that require genetic manipulation (like tagged ubiquitin expression) is its applicability to complex biological samples, including patient tissues [25]. The protocol has been successfully developed and tested using baker's yeast and mammalian cell lysates, and the authors note it can be adapted for other organisms and biological samples [44] [45]. For tissues, effective homogenization and the use of strong denaturants and DUB inhibitors during lysis are critical first steps to access the ubiquitinated proteome.

Experimental Protocol: Enriching Ubiquitinated Proteins from Cell Lysates Using OtUBD Affinity Resin

This protocol outlines the core steps for using OtUBD to enrich ubiquitinated proteins, with notes on how to tailor the process for maximum specificity.

Part 1: Preparation of OtUBD Affinity Resin

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express the recombinant His-tagged OtUBD protein (from plasmids like pET21a-cys-His6-OtUBD) in E. coli. Purify the protein using Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC) with a Ni-NTA agarose column [45].

- Coupling to Resin: Couple the purified OtUBD protein to a solid support, such as SulfoLink Coupling Resin, via cysteine residues. As per the protocol, use 2-4 mg of OtUBD per 1 mL of resin slurry.

- Quenching and Storage: After coupling, block any remaining reactive sites on the resin with L-cysteine. Store the prepared OtUBD resin in a storage buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.02% sodium azide) at 4°C [45].

Part 2: Cell Lysis and Pulldown Procedure

The following workflow details the critical decision points for specificity.

Key Buffers and Reagents:

- Native Lysis/Binding Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM NEM, and protease inhibitors [45] [43].

- Denaturing Lysis/Binding Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 4-6 M Urea, 1 mM NEM, and protease inhibitors. Note: The lysate may need to be diluted to reduce SDS concentration before pulldown. [44] [45]

- Wash Buffers: Prepare corresponding wash buffers (with or without denaturants) but without detergents or with reduced detergent concentrations.

Part 3: Elution and Downstream Analysis

Elute bound proteins by boiling the resin in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The eluates can then be analyzed by:

- Immunoblotting: Using anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1) to confirm enrichment [45].

- Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): For proteomic profiling of the ubiquitylome or interactome [44] [43] [46].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for OtUBD-Based Research

Table: Essential Reagents for Implementing the OtUBD Method

| Reagent/Solution | Function in the Protocol | Key Specificity Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant OtUBD | The core affinity ligand for ubiquitin. | High intrinsic affinity allows for efficient capture of monoUb and polyUb conjugates without chain-type bias [43] [42]. |

| SulfoLink Coupling Resin | Solid support for immobilizing OtUBD. | Covalent coupling via cysteine ensures OtUBD does not leach off the resin during denaturing conditions [45]. |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitor. | Critical for preserving the native ubiquitination state by preventing DUB-mediated deubiquitination during sample preparation [45] [43]. |

| Urea | Denaturant used in the "ubiquitylome" protocol. | Disrupts non-covalent protein interactions, eliminating proteins that merely associate with ubiquitin or ubiquitinated substrates [44] [46]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents proteolytic degradation of proteins. | Maintains protein integrity throughout the purification, ensuring accurate identification of full-length ubiquitinated species. |

Within ubiquitinated protein enrichment research, the initial step of cell lysis is critical. The choice between denaturing and native lysis buffers directly dictates the preservation or disruption of non-covalent interactions that can lead to non-specific binding. Selecting the appropriate conditions is fundamental to reducing background noise, improving target specificity, and ensuring the reliability of downstream analyses. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to help you optimize this key step.

Core Concepts: Denaturing vs. Native Lysis Buffers

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between these two buffer types and their suitability for various research goals.

Table 1: Characteristics of Denaturing and Native Lysis Buffers

| Feature | Denaturing Buffers | Native Buffers |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Disrupts non-covalent interactions; unfolds proteins | Preserves non-covalent interactions; maintains protein complexes and native state |

| Typical Components | SDS, Urea, Guanidine-HCl | Non-ionic (e.g., Triton X-100, NP-40) or zwitterionic detergents |

| Impact on Non-Specific Binding | Reduces by denaturing and inactivating non-target proteins | Can increase by allowing non-specific protein-protein interactions to persist |

| Compatibility with Ubiquitin Enrichment | Excellent for mass spectrometry; prevents deubiquitinase (DUB) activity | Required for certain affinity tags (e.g., TUBE) that rely on native ubiquitin structure |

| Best for Research Aimed At | Identifying ubiquitination sites and linkage types | Studying ubiquitinated protein complexes and functional interactions |

The workflow below illustrates the decision-making process for selecting a lysis buffer in the context of ubiquitinated protein enrichment.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment Under Denaturing Conditions

This protocol is optimized for mass spectrometry-based identification of ubiquitination sites, as it effectively minimizes non-specific binding and halts enzymatic activity [6].

Reagents Needed:

- Lysis Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 1x Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (add fresh).

- Wash Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Sodium Deoxycholate.

- Elution Buffer: 1x SDS-PAGE Loading Buffer with 100 mM DTT, or 0.1 M Glycine-HCl (pH 2.5-3.0) for immediate neutralization [26].

Procedure:

- Lysis: Resuspend cell pellets in a pre-warmed (95°C) denaturing lysis buffer. Immediately vortex and heat at 95°C for 5-10 minutes to fully denature proteins [6].

- Clarification: Cool the lysate and dilute it 10-fold with a buffer containing 1.0% non-ionic detergent (e.g., Triton X-100) to reduce the SDS concentration to a level compatible with your enrichment resin (0.1%). Centrifuge at 20,000 x g for 15 minutes to remove insoluble debris [47].

- Enrichment: Incubate the clarified supernatant with your chosen enrichment resin (e.g., Ubiquitin Binding Domain (UBD) beads, linkage-specific antibodies, or His/Strep-Tactin for tagged ubiquitin) for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle mixing [6] [41].

- Washing: Pellet the beads and wash 3-4 times with the wash buffer. A high-salt wash (e.g., with 500 mM NaCl) can be incorporated to further reduce ionic non-specific binding [26].

- Elution: Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins using your chosen elution buffer. For downstream MS analysis, on-bead digestion with trypsin can be performed directly.

Protocol: Protein Extraction Using Phenol-SDS for Recalcitrant Samples

For difficult tissues rich in phenolics, proteases, or fats, a phenol-based method can be superior for clean protein extraction, which is a prerequisite for effective enrichment [48].

Reagents Needed:

- SDS Buffer: 30% Sucrose, 2% SDS, 0.1 M Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 5% β-mercaptoethanol.

- Tris-Buffered Phenol (pH 8.0).

- Precipitation Solution: 0.1 M Ammonium Acetate in Methanol.

Procedure:

- Homogenize: Grind tissue (1g) in liquid nitrogen and extract with SDS buffer.

- Sonication: Sonicate the extract 6 times for 15 seconds on ice to ensure complete disruption [48] [49].

- Phenol Extraction: Add an equal volume of Tris-buffered phenol. Vortex for 10 minutes at 4°C. Centrifuge at 8,000 x g for 10 minutes.

- Precipitation: Collect the phenolic phase and re-extract with SDS buffer. Re-precipitate the pooled phenolic phase overnight with four volumes of precipitation solution at -20°C.

- Wash & Solubilize: Pellet the protein by centrifugation, wash with cold ammonium acetate and acetone, and air-dry. Resolubilize the pellet in your desired lysis buffer for subsequent ubiquitin enrichment [48].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Problem: My ubiquitinated protein enrichment shows high non-specific background.

- Cause: Native lysis conditions allow non-specific protein complexes to persist and co-purify.

- Solution: Switch to a denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., with 1% SDS). Ensure the buffer is ice-cold and protease inhibitors are added fresh. Increase the number of washes and include a high-salt (150-500 mM NaCl) wash step [47] [26] [49].

Problem: I am getting low yield of my target ubiquitinated protein.

- Cause (1): The lysis buffer is inefficient at extracting the target protein, especially if it's membrane-bound or in a protein aggregate.

- Solution (1): Optimize the detergent. For membrane proteins, try a zwitterionic detergent like CHAPS or a higher concentration of an ionic detergent like SDS. For very insoluble proteins, use denaturants like urea or guanidine-HCl [47] [49].

- Cause (2): The ubiquitin tag is sterically hindered or removed by active deubiquitinases (DUBs) during lysis.

- Solution (2): Use a denaturing buffer to inactivate DUBs instantly. Alternatively, include DUB inhibitors in your native lysis buffer [6].

Problem: My protein is precipitating or degrading during extraction.

- Cause: Inefficient homogenization or inactive protease inhibitors.

- Solution: For tissues, use cryogenic grinding or a high-throughput homogenizer. Always add fresh protease inhibitors to the lysis buffer immediately before use. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles of lysates [49].

FAQ: When must I use a native lysis buffer? A native buffer is essential when your enrichment strategy relies on the native structure of a protein complex. This includes methods using Tandem Hybrid UBDs (ThUBDs) or when you need to co-purify a ubiquitinated protein with its interacting partners for functional studies [41].

FAQ: How does buffer pH affect non-specific binding? Most affinity purifications use buffers at physiologic pH (e.g., PBS) to maintain binding interactions. Ensuring your lysis and binding buffers are at the correct pH (typically 7.2-7.5) is crucial, as an incorrect pH can promote non-specific ionic binding [26] [50].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Detergents (SDS) | Core component of denaturing buffers; disrupts non-covalent interactions and coats proteins with negative charge [49]. | Must be diluted (<0.1%) before enrichment steps to avoid damaging affinity resins. |

| Non-Ionic Detergents (Triton X-100, NP-40) | Core component of native buffers; solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving protein-protein interactions [49]. | Typical concentration is 0.1-1%. A limiting amount can cause poor lysis yield [47]. |

| Urea & Guanidine-HCl | Chaotropic agents used in strong denaturing buffers; break non-covalent interactions to fully denature proteins [49]. | Useful for solubilizing insoluble proteins from inclusion bodies [47]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevents proteolytic degradation of target proteins and ubiquitin chains during extraction [49]. | Must be added fresh to the lysis buffer immediately before use for maximum efficacy [47]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | Used in antibody-based enrichment to isolate proteins with specific Ub chain linkages (e.g., K48, K63) [6]. | Enables study of linkage-specific biology but can be costly and may have non-specific binding. |

| Tandem Hybrid UBDs (ThUBDs) | Engineered high-affinity domains for enriching endogenous ubiquitinated proteins under native conditions without genetic tagging [41]. | Superior to single UBDs for capturing a wider range of ubiquitinated substrates from complex lysates. |

In the pursuit of studying ubiquitination—a critical post-translational modification regulating protein stability, activity, and localization—researchers consistently face the challenge of non-specific binding during the enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins. This interference compromises sample purity, yield, and the reliability of downstream analyses. Competitive elution, a technique that uses specific agents to displace target molecules from affinity resins, provides a powerful strategy to mitigate this. This technical support center elaborates on the application of two primary competitive elution agents—Imidazole and Free Ubiquitin—within the context of ubiquitination research. It provides detailed troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers and drug development professionals optimize their protocols for cleaner recoveries and more robust experimental outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is competitive elution and how does it reduce non-specific binding?

Competitive elution is a chromatography technique where a soluble molecule that competes for the binding site on the affinity resin is used to gently and specifically displace the target protein. In contrast to harsh, non-specific elution methods like low pH or high concentrations of denaturants, competitive elution minimizes the co-elution of proteins that are stuck to the resin or the tags of the target protein itself. This results in a purer final sample. For example, imidazole competes with polyhistidine-tagged proteins for coordination sites on immobilized nickel ions in immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) [51].

2. When should I use imidazole versus free ubiquitin for competitive elution?

The choice depends entirely on your affinity purification strategy and the nature of the non-specific binding you aim to reduce.

| Elution Agent | Primary Use Case | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imidazole | Eluting His-tagged proteins (e.g., tagged Ub, E1, E2, or E3 enzymes) from Ni-NTA or similar IMAC resins [51]. | Competes with the His-tag for coordination sites on the immobilized nickel ions. | Effectively disrupts the specific interaction between the tag and the resin, preventing co-elution of non-His-tagged contaminants. |

| Free Ubiquitin | Eluting ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD)-containing proteins or ubiquitinated substrates from ubiquitin-coated resins or linkage-specific Ub chains from UBD-based resins [6]. | Competes with resin-bound ubiquitin for the UBD on your protein of interest. | Highly specific for the ubiquitin-protein interaction, preserving the integrity of Ub chains on substrates. |

3. I am purifying an untagged E3 ligase like Nedd4. How can competitive elution help?

Even when the final goal is an untagged protein, competitive elution can be a vital step in an orthogonal affinity tag strategy. In a documented purification of full-length human Nedd4, the enzyme was initially expressed with a cleavable N-terminal GST tag and a His-tag [51]. The first purification step used glutathione affinity resin. The tags were then cleaved off, and the sample was applied to a nickel resin. In this second step, imidazole was used in the wash buffer (20 mM) to compete away any E. coli proteins that non-specifically bound to the nickel resin through their surface histidines. The untagged Nedd4, which no longer had a His-tag, flowed through the column in a highly pure state, while contaminants were retained and later eluted with a high-imidazole gradient [51].

4. What are the typical concentrations used for imidazole elution?

Imidazole is typically used in a step-wise or gradient elution. The exact concentration required for elution depends on the binding strength of the His-tagged protein, but standard ranges are well-established [51]:

| Solution | Imidazole Concentration | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Equilibration/Wash Buffer | 0 - 20 mM | To prepare the column and wash away weakly bound, non-specific proteins. |

| Low-Stringency Elution | 20 - 250 mM (gradient) | To elute the target His-tagged protein. |

| High-Stringency Elution | 250 - 500 mM | To elute any remaining tightly-bound contaminants and regenerate the column. |

5. Why might my competitive elution still result in a low yield of my ubiquitinated protein?

Low yield after competitive elution can be attributed to several factors. The affinity of the interaction might be extremely high, requiring optimization of the competitor concentration (e.g., higher free ubiquitin). The stoichiometry of ubiquitination is often very low under physiological conditions, making detection inherently challenging [6]. Furthermore, ubiquitinated proteins and Ub chains themselves can be degraded by co-purifying deubiquitinases (DUBs) if protease inhibitors are not included in all buffers.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Background of Non-Specifically Bound Proteins

Potential Cause #1: Inadequate Washing with Competitive Agent Before Elution Non-specific proteins, particularly in bacterial lysates, can bind to IMAC resins via surface histidine residues.

- Solution: Incorporate a low concentration of a competitive agent (e.g., 20-40 mM imidazole) in the wash buffer before the final elution step. This will displace weakly bound contaminants without eluting your target His-tagged protein [51].

- Protocol Example:

- Load clarified lysate onto Ni-NTA column.

- Wash with 10-15 column volumes (CV) of standard wash buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris, 250 mM NaCl, pH 7.4).

- Wash with 5-10 CV of wash buffer supplemented with 20 mM imidazole.

- Elute with wash buffer containing 250 mM imidazole.