The β-Grasp Fold: From Ubiquitin's Structure to Versatile Functions and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the β-grasp fold, a structurally simple yet functionally versatile protein scaffold.

The β-Grasp Fold: From Ubiquitin's Structure to Versatile Functions and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the β-grasp fold, a structurally simple yet functionally versatile protein scaffold. We explore the evolutionary origins and core structural architecture of this fold, best known for its role in ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs). The content details the experimental and computational methodologies used to study β-grasp proteins, addresses key challenges in probing their dynamics and interactions, and compares the diverse functional families within this superfamily. By integrating foundational knowledge with current research, we highlight the significant implications of targeting β-grasp fold pathways, particularly the ubiquitin-proteasome system, for developing novel therapeutics in areas such as cancer, neurodegenerative, and infectious diseases.

The Architectural Blueprint and Evolutionary History of the β-Grasp Fold

The β-grasp fold (β-GF) represents a fundamental and versatile structural motif in protein architecture, prototyped by the ubiquitous protein ubiquitin (UB) [1]. This compact fold is characterized by a β-sheet that appears to "grasp" a single α-helical segment, forming a stable scaffold that has been recruited for a strikingly diverse range of biochemical functions across all domains of life [1]. Its discovery in ubiquitin, a key regulator of protein stability and signaling in eukaryotes, initially highlighted its importance. Subsequent structural studies have revealed its presence in a vast array of proteins with functionally distinct roles, including sulfur transfer, RNA binding, enzymatic activity, and adaptor functions in signaling complexes [1]. This in-depth technical guide delineates the core structural features of the β-grasp fold, its evolutionary trajectory, and its functional plasticity, with a specific focus on its implications for ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like protein (Ubl) research. Understanding this fold is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals, as it forms the structural basis for critical cellular processes, and its dysregulation is often implicated in disease.

Core Structural Features of the β-Grasp Fold

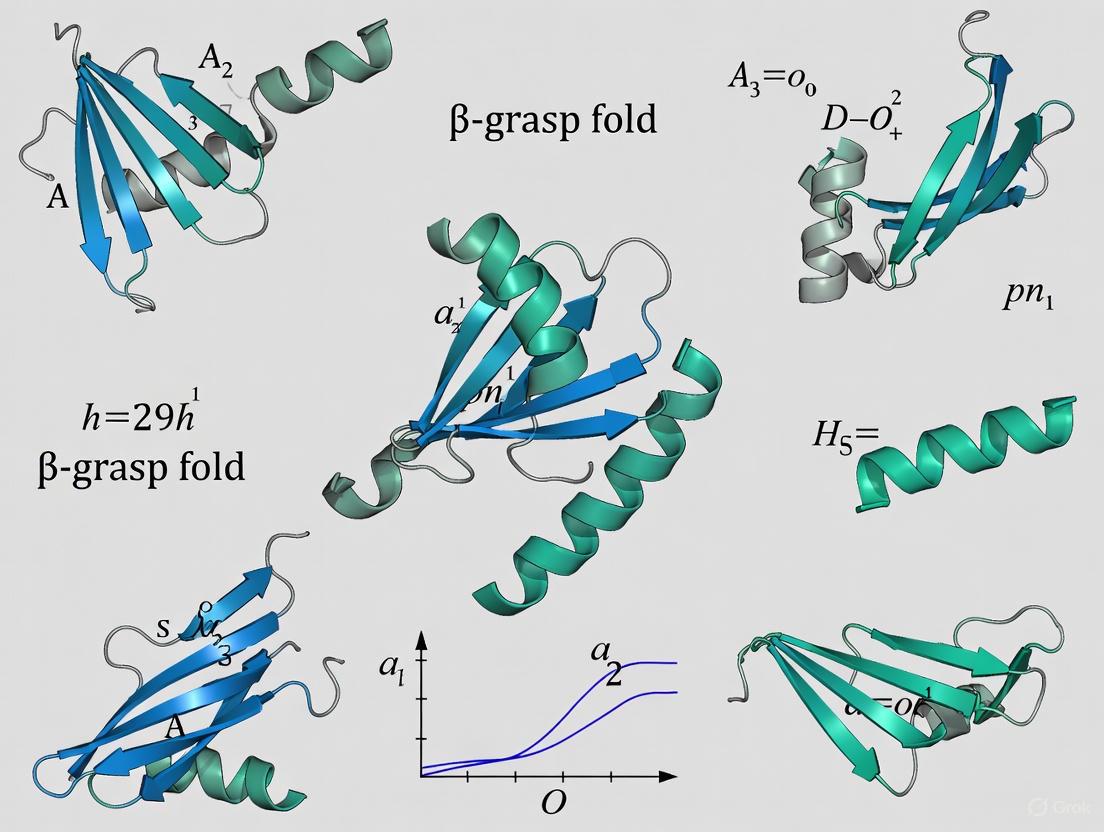

The β-grasp fold is defined by a conserved core structure that serves as a stable platform for functional diversification. The defining characteristic is a β-sheet composed of four to five anti-parallel β-strands that form a twisted, exposed surface. This sheet "grasps" a single α-helical segment that is positioned diagonally across the sheet [1]. The core structural elements are consistently arranged in a specific order, forming the classic β-grasp topology.

Table 1: Core Structural Elements of the β-Grasp Fold

| Structural Element | Description | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| β-Sheet | 4-5 anti-parallel strands; provides a large, exposed interaction surface. | Primary site for interactions with diverse partners (proteins, RNA, ligands, co-factors) [1]. |

| α-Helix | Single helical segment; positioned between strands 2 and 3 of the core fold. | Stabilizes the core structure; can participate in specific binding interactions. |

| Loop Regions | Variable connectors between secondary structures; often contain specific inserts. | Major source of functional diversification; can form binding pockets or active sites [2]. |

The structural versatility of the β-GF arises primarily from its prominent β-sheet, which provides an exposed surface for diverse interactions. In some cases, this sheet can also form open barrel-like structures to accommodate other functions [1]. Beyond the core, the fold is subject to numerous elaborations, including inserts of additional secondary structures, such as the β-hairpin found in the transcobalamin-like clade of the SLBB superfamily, which plays a direct role in ligand binding [2]. These structural variations, while adorning the core, do not obscure the fundamental β-grasp topology, which remains readily identifiable.

Diagram 1: The core β-grasp fold structure and its functional versatility.

The β-Grasp Fold in Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-Like Proteins

The ubiquitin superfamily represents a major radiation of the β-grasp fold within eukaryotes. Ubiquitin itself is a 76-residue polypeptide that adopts the classic β-GF, with a five-stranded β-sheet and a single α-helix [1]. This structural scaffold is not only stable but also serves as the foundation for a vast post-translational modification system. Other Ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubls), such as SUMO, Nedd8, Apg12, and Urm1, share the same core fold and are conjugated to target proteins via a cascade of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes [1]. This system allows for the precise regulation of protein stability, localization, and activity.

The origin of the eukaryotic ubiquitin system is deeply rooted in more ancient bacterial metabolic pathways. Sensitive sequence and structural analyses have revealed that ubiquitin is closely related to bacterial sulfur carrier proteins like ThiS and MoaD, which are involved in thiamine and molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis, respectively [1]. These bacterial proteins also possess a C-terminal glycine that forms a thiocarboxylate, catalyzed by enzymes (ThiF/MoeB) that are structural and mechanistic ancestors of the eukaryotic E1 enzyme [1]. This evolutionary connection highlights a remarkable functional shift: a fold and associated enzymatic machinery originally used for sulfur transfer in core metabolism were co-opted in eukaryotes to form a sophisticated protein-tagging system. The eukaryotic phase of β-GF evolution was marked by a specific expansion of UB-like members, leading to at least 67 distinct families, with 19-20 families already present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor [1].

Functional Diversity and Evolutionary History

The functional repertoire of the β-grasp fold is extraordinarily diverse, extending far beyond the ubiquitin superfamily. Systematic analyses show that this small fold has been independently recruited for multiple distinct biochemical activities throughout evolution [1].

Table 2: Functional Diversity of the β-Grasp Fold

| Functional Category | Example Protein/Domain | Specific Function | Independent Evolutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-translational Modification | Ubiquitin, SUMO, ThiS, MoaD | Protein or sulfur carrier conjugation [1]. | Multiple |

| Enzymatic Activity | NUDIX phosphohydrolases | Hydrolysis of diverse substrates [1]. | ≥ 3 |

| Co-factor Binding | 2Fe-2S Ferredoxin, Molybdopterin-binding | Electron transport, redox reactions [1]. | ≥ 3 (co-factors), ≥ 2 (Fe-S clusters) |

| Soluble Ligand Binding | SLBB Superfamily (e.g., Transcobalamin) | Vitamin B12 binding and uptake [2]. | Multiple |

| RNA Binding | TGS Domain | Binding tRNA and other RNAs [1]. | Multiple |

| Protein-Protein Interaction | RA, PB1, FERM domains | Adaptors in signaling complexes [1]. | Multiple |

Evolutionary reconstruction indicates that the β-grasp fold is ancient, having differentiated into at least seven distinct lineages by the time of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) [1]. The earliest members were likely involved in RNA metabolism and related functions [1]. Subsequently, the fold radiated into various functional niches. Most of the structural diversification occurred in prokaryotes, while the eukaryotic phase was characterized by a dramatic expansion of Ub-like domains and an increase in the domain architectural complexity of proteins, facilitating their use in numerous adaptor roles [1]. A notable example of ongoing discovery is the identification of the SLBB superfamily, a novel group of β-GF domains that bind soluble ligands like vitamin B12 [2].

Diagram 2: Evolutionary history of the β-grasp fold from LUCA to eukaryotes.

Experimental Protocols for β-Grasp Fold Analysis

Identification of Novel β-Grasp Fold Members

The small size and high divergence of β-GF members make exhaustive identification challenging. A multi-pronged computational strategy is required [1].

Materials:

- Structural Datasets: Protein Data Bank (PDB), SCOP database.

- Sequence Databases: NCBI Non-Redundant (NR) database.

- Software Tools: PSI-BLAST, DALI, HMMER package, T-Coffee multiple alignment tool.

Methodology:

- Seed Collection: Compile a set of known β-GF structures from PDB and SCOP as initial seeds [1].

- Iterative Sequence Profiling: Use seeds to perform PSI-BLAST searches against the NR database. Iterate until convergence (e-value threshold e < 0.01), collecting statistically significant hits [1].

- Structural Similarity Searches: Use programs like DALI to perform structural comparisons with known β-GF domains. Retrieve hits with significant Z-scores (e.g., Z > 5-7) [2].

- Transitive Searches and Model Building: Use newly detected members to initiate further iterative searches. Construct Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and Position-Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSMs) from alignments to search for more divergent homologs in sequenced genomes [1] [2].

- Multiple Alignment and Classification: Align sequences using a tool like T-Coffee, guided by structural superpositions. Analyze the alignment to identify conserved core features (e.g., glycine residues) and classify sequences into families and superfamilies (e.g., the SLBB superfamily) [2].

Structural and Functional Characterization

Once identified, potential β-GF domains require experimental validation and functional insight.

Materials:

- Cloning and Protein Purification Systems: (e.g., E. coli expression vectors, chromatography equipment).

- Crystallization Trays and X-ray Source: For X-ray crystallography.

- NMR Spectrometer: For solution-state structure determination.

- Functional Assays: (e.g., enzyme activity assays, binding measurements like ITC/SPR).

Methodology:

- Structure Determination:

- X-ray Crystallography: Purify the protein, grow crystals, and solve the structure via molecular replacement or experimental phasing. The structure will confirm the presence of the core β-GF (β-sheet grasping a helix) and reveal any unique inserts (e.g., the β-hairpin in transcobalamin) [3] [2].

- NMR Spectroscopy: For smaller, soluble β-GF domains (like ubiquitin), NMR can be used to determine the solution-state structure and study dynamics.

- Functional Analysis:

- Ligand Binding Studies: Co-crystallize the β-GF domain with its proposed ligand (e.g., vitamin B12 for transcobalamin) or perform binding assays. Analyze the structure to identify contact residues from the core sheet and variable inserts [2].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Mutate conserved residues (e.g., the glycines in the SLBB superfamily or residues in the binding interface) to confirm their role in fold stability and function.

- Structure Determination:

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| PSI-BLAST | Sensitive sequence database searching to identify divergent homologs [1]. |

| DALI Server | Structural similarity searches to detect β-GF folds based on 3D shape [2]. |

| HMMER Suite | Building and searching with probabilistic models (HMMs) for remote homology detection [2]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository of 3D structural data for use as search seeds and comparative analysis [1]. |

| E. coli Expression Systems | Standard platform for recombinant overexpression of β-GF domain proteins for purification. |

| Crystallization Kits | Sparse matrix screens to identify initial conditions for growing protein crystals. |

| Ubiquitin (Wild-type & Mutants) | Essential control and reference molecule for studies of UB/Ubl structure and function. |

Ubiquitin, a 76-residue regulatory protein, serves as the prototypical member of the β-grasp fold (β-GF), a structural archetype distinguished by its remarkable functional versatility and evolutionary conservation. This fold is characterized by a β-sheet that appears to "grasp" an α-helical segment, forming a compact globular structure [1] [4]. Despite its small size, the β-grasp fold has been recruited for a stunning array of biochemical functions, including post-translational modification, sulfur transfer, RNA binding, enzymatic catalysis, and small molecule coordination [1] [2] [5]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the ubiquitin fold, detailing its structural features, evolutionary relationships, and the experimental methodologies central to its study. Framed within ongoing research on ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubls), this guide aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the structural and mechanistic insights necessary to navigate this complex protein family and exploit its therapeutic potential.

The discovery of the ubiquitin fold marked a pivotal advancement in molecular biology. Initially identified as a post-translational modification signal, ubiquitin's structure was first resolved in the 1980s [6]. Structural analyses revealed that ubiquitin's fold was not unique but was shared by functionally disparate proteins, leading to the formal definition of the β-grasp fold [1] [5]. This fold is characterized by a core structure comprising a mixed β-sheet of four to five strands that clutches a single α-helix between its second and third strands [1] [6]. The N and C termini are strategically positioned in close proximity, a feature critical for its function in conjugation [7] [6].

Evolutionary reconstruction indicates that the β-grasp fold had already diversified into at least seven distinct lineages by the time of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), encompassing much of the structural diversity seen today [1]. The earliest members were likely involved in RNA metabolism and sulfur transfer operations in prokaryotic systems [1]. The eukaryotic lineage witnessed a specific and dramatic expansion of ubiquitin-like (Ubl) members, with the eukaryotic UB superfamily diversifying into at least 67 distinct families [1] [5]. A key innovation in eukaryotes was the integration of Ubl domains into complex multidomain proteins, increasing the architectural complexity of proteins involved in signaling and adaptor roles [1]. This evolutionary history establishes ubiquitin not as an outlier, but as a highly specialized derivative of an ancient and versatile structural scaffold.

Structural Bioinformatics of the β-Grasp Fold

Core Architectural Principles

The β-grasp fold is defined by a conserved core structure that can be elaborated upon through various inserts and extensions, giving rise to its functional diversity. The canonical fold, as prototyped by ubiquitin, includes the following elements [6]:

- A central, mixed β-sheet: Typically composed of five anti-parallel strands arranged with a -1, +3x, +1x, -2x topology [6].

- An α-helix: Positioned between the second and third β-strands, which is "grasped" by the β-sheet.

- A 3₁₀ helix: A shorter helical segment is also commonly present.

The stability of the fold is remarkable, with ubiquitin maintaining its structure across a pH range of 1.18–8.48 and temperatures up to 80°C, exhibiting a melting point near 100°C [6]. This stability is primarily due to extensive intra-hydrogen bonding and a well-packed hydrophobic core, as the fold contains no disulfide bonds, metal ions, or cofactors [6].

Table 1: Secondary Structural Elements of Human Ubiquitin (PDB: 1UBQ)

| Element Type | Start Residue | End Residue | Description | Sequence/Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Helix | 23 | 34 | 3.5-turn α-helix | IENVKAKIQDKE |

| 3₁₀ Helix | 56 | 59 | Short 3₁₀ helix | LSDY |

| β-Strand 1 | 2 | 7 | N-terminal strand | QIFVKT |

| β-Strand 2 | 12 | 16 | TITLE | |

| β-Strand 3 | 41 | 45 | QRLIF | |

| β-Strand 4 | 48 | 49 | KQ | |

| β-Strand 5 | 66 | 71 | C-terminal strand | TLHLVL |

| β-Turn 1 | 7 | 10 | Type I | TLTG |

| β-Turn 2 | 18 | 21 | Type I | EPSD |

| β-Hairpin 1 | 2-7 | 12-16 | 3:5 hairpin |

Functional Versatility and Structural Elaborations

The manifold functions of the β-grasp fold arise primarily from its prominent β-sheet, which provides an exposed surface for diverse interactions [1]. This surface can mediate protein-protein, protein-RNA, and protein-ligand interactions. In some cases, the sheet can curve to form open barrel-like structures for binding larger ligands or cofactors [1].

Systematic analysis has shown that this small fold has independently evolved to support a wide range of biochemical activities on multiple occasions [1]:

- Enzymatic active sites: Recruited as a scaffold for different enzymes, such as NUDIX phosphohydrolases, on at least three independent occasions.

- Cofactor binding: The binding of diverse cofactors like iron-sulfur clusters and molybdopterin has evolved independently at least three times.

- Soluble ligand binding: A novel superfamily termed the Soluble-Ligand-Binding β-grasp (SLBB) domain was identified, which includes proteins like transcobalamin (vitamin B12 binding), bacterial polysaccharide export proteins, and the Nqo1 subunit of NADPH-quinone oxidoreductase [2].

Table 2: Major Functional Classes of β-Grasp Fold Proteins

| Functional Class | Representative Members | Key Structural Features | Independent Evolutionary Origins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-translational Modifiers | Ubiquitin, SUMO, NEDD8, Atg8, Atg12 | Conserved C-terminal glycine for conjugation, exposed hydrophobic patch (Ile44) [1] [6] | Derived from sulfur carrier systems (ThiS/MoaD) [1] |

| Sulfur Carriers | ThiS, MoaD | C-terminal thiocarboxylate, similarity to Ub fold [1] [8] | Ancient, predating Ub |

| Enzymatic Scaffolds | NUDIX hydrolases, Staphylokinases | Active site residues positioned on loops of the β-sheet [1] | At least 3 |

| Iron-Sulfur Cluster Binding | 2Fe-2S Ferredoxins | Cysteine residues ligating the cluster [1] [2] | At least 2 |

| Soluble Ligand Binding (SLBB) | Transcobalamin, Nqo1, ComEA | Inserts for ligand specificity (e.g., β-hairpin in transcobalamin) [2] | At least 2 major clades (Transcobalamin, Nqo1) |

| RNA Binding | TGS domain, IF3, RPB2 subunit | Positive surface patches for nucleic acid interaction [1] | Multiple |

| Protein Interaction Adapters | RA, PB1, FERM-N domains | Surface loops and strands for specific protein binding [1] | Multiple |

The SLBB superfamily exemplifies how structural variations enable new functions. The transcobalamin-like clade is defined by a β-hairpin insert after the core helix, which directly contacts the vitamin B12 ligand [2]. In contrast, the Nqo1-like clade features a distinct insert between strands 4 and 5 of the core fold [2]. Despite different inserts, both clades likely bind their soluble ligands in a similar spatial location relative to the core fold.

Experimental Analysis of Ubiquitin Structure and Folding

Protocol 1: Atomic-Resolution Folding Studies via Molecular Dynamics

Objective: To characterize the folding mechanism, thermodynamics, and kinetics of ubiquitin at an atomic level using equilibrium molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [7].

Methodology:

- System Setup:

- Initial Structures: Simulations are initiated from both the folded state (e.g., PDB 1UBQ) and an extended, unfolded state.

- Solvation: The protein is solvated in a water box (e.g., ~5,581 TIP3P water molecules) with periodic boundary conditions. System size artifacts should be checked using a larger water box.

- Force Field: Use the CHARMM22* force field, modified to correct proline isomerization balance.

- Electrostatics: Employ a Gaussian Split Ewald (GSE) method for long-range electrostatic interactions with a 10.5 Å cutoff. A simple shifted-force truncation is insufficient as it can produce artificially compact unfolded states.

Simulation Execution:

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the system in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) for 2 ns.

- Production Run: Perform simulations in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) at a temperature near the protein's melting point (e.g., 390 K) to observe spontaneous folding and unfolding events. Use a specialized machine like Anton for the required computational throughput.

- Integration: Use a reference system propagator algorithm (RESPA) scheme with a 5 fs inner and 10 fs outer timestep, which can be facilitated by modifying hydrogen and water oxygen masses.

Data Analysis:

- Transition Path Identification: Identify folding/unfolding transition paths using dual cutoffs on the Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of key secondary structure elements (e.g., residues 2–45 and 65–69).

- Reaction Coordinate Optimization: Optimize a one-dimensional reaction coordinate as a linear combination of the Q-values (native contacts) for individual residues.

- Kinetic and Thermodynamic Analysis: Calculate folding rates and free energy surfaces from the simulations. Φ-values for point mutations can be computed from folding/unfolding rates derived from Langevin dynamics simulations along the optimized reaction coordinate.

- State Clustering: Identify metastable states on the free-energy landscape using kinetic-clustering analysis of Cα–Cα contact autocorrelation functions.

Key Findings: MD simulations reveal that ubiquitin folding is a relatively sequential process following a few dominant paths. The order of formation of native structure is correlated with relative structural stability in the unfolded state. The transition state ensemble (TSE) is characterized by a well-defined folding nucleus in the N-terminal region, involving the α-helix and the first two β-strands, while C-terminal strands are less structured in the TSE [7]. These principles align with those derived from studies of fast-folding proteins.

Protocol 2: Structural Dissection of a Ubiquitin Ligase Complex by Cryo-EM

Objective: To determine the architecture and molecular basis of substrate recognition and ubiquitination by the human HRD1 ubiquitin ligase complex using single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [9].

Methodology:

- Complex Preparation:

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the subcomplex by overexpressing core components (HRD1, SEL1L, and the lectin adapter XTP3B) in HEK293 cells. While native purification is ideal, reconstitution improves yield and homogeneity for structural studies.

- Validation: Conduct functional assays (e.g., monitoring degradation of a known ERAD substrate like CD147) to ensure the reconstituted complex is functional.

- Cryo-EM Workflow:

- Vitrification: Apply purified complex to cryo-EM grids, blot, and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane.

- Data Collection: Collect a large dataset of micrographs using a high-end cryo-electron microscope (e.g., Titan Krios).

- Image Processing:

- Particle picking and 2D classification to select homogeneous particles.

- Ab-initio reconstruction and 3D refinement.

- Perform focused classification and refinement to improve resolution for flexible regions.

- Model Building:

- Dock AlphaFold2-predicted models of components into the cryo-EM density map.

- Manually build and adjust the atomic model in Coot, followed by real-space refinement in Phenix.

Key Findings: The cryo-EM structure of the human HRD1-SEL1L-XTP3B complex revealed that HRD1 forms a dimer, but only one protomer carries the SEL1L-XTP3B complex, forming a 2:1:1 stoichiometry [9]. The structure captured a trimmed N-glycan substrate sandwiched between XTP3B and SEL1L. Furthermore, the engagement of Derlin family proteins was found to induce dramatic conformational changes, breaking the HRD1 dimer and forming a new four-helix bundle from two SEL1L molecules, potentially inducing membrane curvature for retrotranslocation [9].

The following diagram illustrates the key conformational changes in the HRD1 complex induced by Derlin protein binding, as revealed by cryo-EM studies [9].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for the Study of Ubiquitin and β-Grasp Fold Proteins

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM22* Force Field | An all-atom empirical force field for molecular dynamics simulations, optimized for proteins. | Simulating ubiquitin folding and dynamics at atomic resolution [7]. |

| E1-E2-E3 Enzyme Cascade | The three-enzyme cascade (Activating, Conjugating, and Ligating enzymes) for in vitro ubiquitination. | Reconstituting specific ubiquitin linkage formation on target substrates for biochemical study [8]. |

| MLN4924 (Nedd8-Adenylate Analog) | A mechanism-based inhibitor that forms a covalent adduct with NEDD8, inhibiting the NEDD8 E1 enzyme. | Probing the role of neddylation pathways in cells; a tool for targeted protein stabilization [8]. |

| Cryo-EM with Direct Electron Detectors | High-resolution structural biology technique for visualizing large macromolecular complexes in near-native state. | Determining the architecture of large E3 ligase complexes like HRD1 [9]. |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs) | Modular protein domains (e.g., UBA, UIM, NZF) that recognize and non-covalently bind ubiquitin motifs. | As pull-down probes to isolate and identify ubiquitylated proteins from cell lysates [6]. |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) for DUBs | Suicide substrates that covalently label the active site of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). | Profiling active DUBs in complex proteomes and inhibitor screening [6]. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Engineered multimeric UBDs with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains, protecting them from DUBs. | Protecting polyubiquitin chains during purification and detecting endogenous ubiquitylation [6]. |

Concluding Perspectives and Future Directions

The ubiquitin prototypical β-grasp fold exemplifies a profound principle in structural biology: a simple, stable scaffold can be evolutionarily co-opted for an extraordinary range of biochemical functions. The functional versatility of this fold stems from its prominent β-sheet, which serves as a versatile interaction surface, and its ability to tolerate structural elaborations like inserts and extensions that confer specificity [1] [2]. From its ancient origins in RNA metabolism and sulfur transfer in prokaryotes, the fold radiated into niches including enzyme catalysis, small molecule binding, and, most notably in eukaryotes, the post-translational regulatory system centered on ubiquitin and Ubls [1].

Future research will focus on several frontiers. First, the full scope of the "ubiquitin code" is still being deciphered, including the physiological functions of atypical ubiquitin linkages and crosstalk with other post-translational modifications like phosphorylation [6]. Second, structural studies on full-length, multi-component complexes like HECT ligases and the HRD1 complex are revealing how domain architecture and conformational dynamics regulate ligase activity and specificity [9] [10]. A key finding is the role of "structural ubiquitin" molecules, which are non-covalently bound and contribute to ligase activity and linkage specificity, as seen in yeast Tom1 [10]. Finally, the continued discovery of new β-grasp families and their functions, particularly in prokaryotes and viruses, promises to uncover novel biology and potential therapeutic targets. A deep understanding of this conserved structural archetype is therefore not only fundamental to cell biology but also crucial for pioneering new therapeutic strategies in disease areas ranging from cancer to neurodegeneration.

The β-grasp fold (β-GF) represents a remarkable evolutionary success story in molecular structural adaptation. Characterized by a five-strand antiparallel β-sheet that appears to grasp a single α-helical segment, this compact fold has been recruited for a strikingly diverse range of biochemical functions throughout the history of cellular life [1] [11]. While best known for its role in eukaryotic ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) that regulate protein degradation and signaling, the deepest origins of this fold predate the emergence of eukaryotes by billions of years [1] [11]. This whitepaper examines the evolutionary journey of the β-grasp fold from its primordial manifestations in prokaryotic systems to its sophisticated regulatory functions in eukaryotic cells, providing researchers with both theoretical frameworks and experimental approaches for investigating these ancient molecular systems.

Evolutionary reconstructions indicate that the β-grasp fold had already differentiated into at least seven distinct lineages by the time of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all extant organisms, encompassing much of the structural diversity observed in modern versions of the fold [1]. The earliest β-grasp members were likely involved in RNA metabolism and subsequently radiated into various functional niches, with most structural diversification occurring in prokaryotes before experiencing specific expansions in eukaryotes [1]. This extensive evolutionary history provides critical context for understanding how simple structural domains can be co-opted for increasingly complex cellular functions across the tree of life.

Evolutionary History and Phylogenetic Distribution

Deep Evolutionary Origins

Molecular clock analyses using pre-LUCA gene duplicates estimate that LUCA lived approximately 4.2 billion years ago (4.09-4.33 Ga), with a genome encoding around 2,600 proteins [12]. This prokaryote-grade anaerobic acetogen possessed an established ecological system, within which early versions of the β-grasp fold likely functioned [12]. The fold appears to have first emerged in the context of translation-related RNA interactions before exploding to occupy various functional niches [11].

The last universal common ancestor contained several β-grasp fold proteins that would subsequently diverge into distinct lineages. Evolutionary reconstruction reveals that the earliest β-grasp members were probably involved in RNA metabolism and subsequently radiated into various functional niches, with most structural diversification occurring in prokaryotes [1]. The eukaryotic phase was mainly marked by a specific expansion of the ubiquitin-like β-grasp members, with the eukaryotic UB superfamily diversifying into at least 67 distinct families, of which at least 19-20 families were already present in the eukaryotic common ancestor [1].

Distribution Across Domains of Life

Table 1: Distribution of β-Grasp Fold Proteins Across Life Domains

| Domain | Representative β-Grasp Proteins | Key Functions | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ThiS, MoaD, TtuB, UBact, BilA, Bub | Sulfur transfer, cofactor biosynthesis, antiphage defense | Single or multiple β-grasp domains, filament-forming variants |

| Archaea | SAMPs (Small Archaeal Modifier Proteins) | Protein conjugation, sulfur transfer | Ubiquitin-like β-grasp, forms polysamp chains |

| Eukaryotes | Ubiquitin, SUMO, NEDD8, ISG15, ATG8, ATG12 | Protein degradation, signaling, autophagy, immune response | Classic Ub-fold, UBL domains with conjugation capability |

The β-grasp fold is widely distributed across all domains of life, though its representation and functional specialization vary significantly [13] [11]. In comparison to eukaryotes, prokaryotic proteins with relationships to UBLs are phylogenetically restricted but demonstrate remarkable functional diversity [13]. For example:

- Bacteria possess ubiquitin-like proteins such as Pup in actinobacteria (though structurally distinct from β-GF) and TtuB in Thermus species, which shares the β-grasp fold and has dual functions as both a sulfur carrier and covalently conjugated protein modification [13].

- Archaea encode small archaeal modifier proteins (SAMPs) that share the β-grasp fold and play a ubiquitin-like role in protein degradation, with some lineages possessing seemingly complete sets of genes corresponding to a eukaryote-like ubiquitin pathway [13].

- Eukaryotes have dramatically expanded the UBL clade, with at least 70 distinct UBL families observed, of which nearly 20 families were probably present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor [11].

Structural and Functional Diversity of β-Grasp Fold Proteins

Core Structural Principles

The β-grasp fold is a small, compact protein fold dominated by a β-sheet with 5 anti-parallel β-strands and a single helical segment [1] [11]. The name derives from the characteristic arrangement where the β-sheet appears to grasp the helical segment [11]. Despite its small size, this fold serves as a multifunctional scaffold in diverse biological contexts [11].

Systematic analysis of all known interactions of the fold shows that its manifold functional abilities arise primarily from the prominent β-sheet, which provides an exposed surface for diverse interactions or additionally, by forming open barrel-like structures [1]. This structural versatility has enabled the fold to be recruited for strikingly diverse biochemical functions, including providing scaffolds for different enzymatic active sites, iron-sulfur clusters, RNA-soluble-ligand and co-factor-binding, sulfur transfer, adaptor functions in signaling, assembly of macromolecular complexes, and post-translational protein modification [1].

Functional Spectrum

Table 2: Functional Diversity of β-Grasp Fold Proteins

| Functional Category | Example Proteins | Organismic Domain | Specific Biochemical Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfur Transfer | ThiS, MoaD, URM1 | Bacteria, Eukarya | Thiamine and molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis |

| Protein Modification | Ubiquitin, SUMO, SAMPs | Eukarya, Archaea | Target proteins for degradation or signaling |

| RNA Binding | TGS domain, IF3 | All domains | Translation regulation, RNA metabolism |

| Enzymatic Activities | NUDIX phosphohydrolases | All domains | Phosphohydrolase activity on diverse substrates |

| Signaling Adaptors | RA, PB1, DCX domains | Eukarya | Mediate protein-protein interactions in signaling |

| Antiphage Defense | BilA, Bub proteins | Bacteria | Conjugate to phage proteins to inhibit virion assembly |

The β-grasp fold demonstrates remarkable functional plasticity, with both enzymatic activities and the binding of diverse co-factors independently evolving on at least three occasions each, and iron-sulfur-cluster-binding on at least two independent occasions [1]. This functional versatility stems from:

- Surface Plasticity: The prominent β-sheet provides an exposed surface for diverse interactions [1].

- Structural Elaborations: Numerous elaborations on the core fold enable functional specialization [1].

- Domain Combinations: Fusion with other domains creates proteins with novel capabilities [14].

In the eukaryotic phase of β-grasp evolution, a key aspect was the dramatic increase in domain architectural complexity of proteins related to the expansion of UB-like domains in numerous adaptor roles [1]. This expansion facilitated the evolution of complex regulatory networks that characterize eukaryotic cellular processes.

Prokaryotic Antecedents of Ubiquitin Signaling

Sulfur Transfer Systems: The Evolutionary Bridge

The evolutionary connection between eukaryotic ubiquitin systems and prokaryotic sulfur transfer machinery represents one of the most compelling examples of molecular exaptation. The first major advances in understanding ubiquitin's origin came with the identification of the sulfur transfer proteins ThiS and MoaD, involved in thiamine and molybdenum cofactor (MoCo) biosynthesis, respectively [11]. These proteins contain β-grasp folds closely related to ubiquitin and form thiocarboxylates at their C-termini, catalyzed by enzymes (ThiF and MoeB) that are strikingly similar to ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1) [11].

The URM1 protein in eukaryotes represents a molecular fossil bridging sulfur carrier and protein modifier functions [13] [11]. Like ThiS and MoaD, URM1 functions as a sulfur carrier through thiocarboxylate formation in the context of tRNA thiolation, but it also undergoes covalent attachment to target proteins in response to oxidative stress, similar to classical ubiquitin-like modifiers [11]. This dual functionality provides a living snapshot of the evolutionary transition from metabolic to regulatory functions.

Prokaryotic Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Systems

Recent research has revealed that bacteria possess biochemical pathways related to eukaryotic ubiquitination that mediate protein conjugation in contexts such as antiphage immunity [14]. These include:

- Bil (Bacterial ISG15-like) Operons: Encode separate E1, E2, Ubl, and deubiquitinase (DUB) proteins that conjugate their Ubl to phage tail proteins during infection to inhibit virion assembly and infectivity [14].

- Bub (Bacterial Ubiquitination-like) Operons: Previously termed "6E" or "DUF6527" operons, encode E1, E2, Ubl, and peptidase proteins that perform protein conjugation [14].

- Type II CBASS Operons: Encode an E2-E1 fusion protein that conjugates the C-terminus of their cognate CD-NTase to unknown targets to activate antiviral signaling [14].

These bacterial Ubls show high structural diversity, with up to three predicted β-grasp domains and diverse fused N-terminal domains [14]. Many form higher-order oligomers, with a large subset containing three β-grasp domains and forming filamentous assemblies in vitro upon calcium ion binding [14]. This filament formation occurs in diverse Ubls from type II Bil, type I Bub, and type II Bub operons, suggesting this property plays an important role in their function, potentially enabling cells to respond to changes in metal ion concentration during phage infection or other stress conditions [14].

Figure 1: Evolutionary relationships between prokaryotic and eukaryotic β-grasp fold proteins, showing functional transitions from metabolic to regulatory roles.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols

Structural Characterization of Bacterial Ubl Oligomerization

The recent discovery of filament-forming bacterial Ubls requires specialized approaches for structural characterization [14]:

Protocol for Ca²⁺-Induced Filament Analysis

- Protein Purification: Express recombinant bacterial Ubls (BilA or Bub) in E. coli Rosetta2 pLysS strains with N-terminal His-tags using pET-based vectors. Purify using nickel-affinity chromatography followed by TEV protease cleavage to remove tags and subsequent size-exclusion chromatography.

- Calcium Titration: Incubate purified Ubls (5-10 mg/mL) with CaCl₂ across a concentration gradient (0-10 mM) in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Structural Analysis:

- Cryo-EM Grid Preparation: Apply 3.5 μL samples to glow-discharged gold grids, blot for 3-5 seconds at 100% humidity, and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane.

- Data Collection: Image using a 300 keV cryo-electron microscope with a K3 direct electron detector at 105,000x magnification.

- Image Processing: Process movies with MotionCor2, followed by CTF estimation in CTFFIND4 and particle picking in cryoSPARC.

- X-ray Crystallography: For crystalline specimens, screen crystallization conditions using sitting-drop vapor diffusion with commercial screens. Collect diffraction data at synchrotron beamlines and solve structures by molecular replacement using known β-grasp domains as search models.

Phylogenetic and Genomic Analysis

Protocol for Evolutionary Reconstruction of β-Grasp Fold Families

- Sequence Identification: Perform iterative PSI-BLAST searches of non-redundant databases using known β-grasp domains as queries (E-value threshold < 0.01) [1].

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Align identified sequences using MAFFT or MUSCLE with structural guidance where available.

- Gene Tree Reconstruction: Construct maximum likelihood trees using IQ-TREE or RAxML with best-fit model selection and 1000 bootstrap replicates.

- Reconciliation Analysis: Use the ALE (Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation) algorithm to reconcile gene trees with species trees, inferring duplications, transfers, and losses [12].

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Reconstruct ancestral sequences at key nodes (including LUCA) using empirical Bayesian methods as implemented in PAML.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Prokaryotic Ubl Systems

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | E. coli Rosetta2 pLysS, pET vectors | Recombinant protein production | Optimized for toxic protein expression |

| Purification Tools | Nickel-NTA resin, TEV protease, Size-exclusion columns | Protein purification and tag removal | Maintain reducing conditions for cysteine mutants |

| Crystallization Screens | Commercial sparse matrix screens (Hampton Research) | Protein crystallization | Screen with/without Ca²⁺ for filamentous Ubls |

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM facilities, Synchrotron access | High-resolution structure determination | Cryo-EM essential for filamentous assemblies |

| Bioinformatics Tools | PSI-BLAST, MAFFT, IQ-TREE, ALE | Sequence analysis and phylogenetics | Iterative searches crucial for distant homologs |

| Antibodies | Custom anti-Ubl antibodies, His-tag antibodies | Detection and immunoprecipitation | Validate native expression in host systems |

Research Implications and Future Directions

Basic Research Applications

Understanding the evolutionary origins of ubiquitin signaling provides fundamental insights with broad research applications:

- Protein Engineering: The structural plasticity of the β-grasp fold enables engineering of novel protein modifiers with customized specificities [1] [14].

- Evolutionary Analysis: Comparative studies of Ubl systems across domains reveal general principles of molecular evolution and functional diversification [1] [11].

- Systems Biology: Mapping complete Ubl networks in prokaryotes reveals primordial regulatory architectures that evolved into eukaryotic complexity [14] [11].

Therapeutic Opportunities

The emerging understanding of prokaryotic Ubl systems creates novel therapeutic avenues:

- Antimicrobial Strategies: Targeting bacterial Ubl pathways involved in antiphage defense could disrupt bacterial immunity or create new antiviral approaches [14].

- Cancer Therapeutics: Understanding the deep evolutionary origins of ubiquitin signaling may reveal conserved structural features that can be targeted for proteostasis manipulation in cancer cells [15].

- Immunomodulation: As bacterial Ubl systems interact with host ubiquitin pathways during pathogenesis, these interfaces represent potential targets for anti-infective strategies [13].

Unanswered Questions and Research Frontiers

Despite significant advances, key questions remain about prokaryotic antecedents of ubiquitin signaling:

- Mechanistic Details: How do bacterial E1-E2-E3 cascades achieve specificity in the absence of the extensive regulatory networks characteristic of eukaryotic systems? [14] [11]

- Physiological Roles: What are the native functions of bacterial Ubl conjugation systems beyond antiphage defense? [14]

- Evolutionary Transitions: What specific evolutionary steps transformed sulfur-carrier systems into protein modifiers? [13] [11]

- Structural Plasticity: How do the architectural variations in bacterial Ubls (multiple domains, oligomerization) relate to their functional specialization? [14]

Future research should focus on combining comparative genomics with experimental characterization of diverse prokaryotic Ubl systems to build a more complete picture of how this remarkable protein fold has been adapted and readapted throughout evolutionary history.

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for investigating prokaryotic ubiquitin-like systems, combining bioinformatic, structural, and functional approaches.

The investigation of prokaryotic antecedents of ubiquitin signaling has transformed our understanding of one of biology's most important regulatory systems. What was once considered a eukaryotic innovation is now recognized as having deep evolutionary roots extending back to LUCA, with functional precursors in prokaryotic sulfur transfer systems that were progressively co-opted for regulatory functions [1] [11]. The recent discovery of sophisticated bacterial ubiquitination-like pathways involved in antiphage defense demonstrates that protein conjugation systems continue to evolve novel functions in prokaryotic contexts [14].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these evolutionary insights provide valuable perspectives for manipulating ubiquitin signaling in therapeutic contexts. The structural and functional diversity of β-grasp proteins across life domains represents a rich source of mechanistic insights and potential engineering templates. As research continues to unravel the molecular complexities of these ancient systems, our ability to harness their principles for basic research and therapeutic applications will undoubtedly expand, potentially leading to new classes of therapeutics that target the deep evolutionary foundations of cellular regulation.

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) represents a pivotal stage in early evolution, possessing a complex cellular structure with a genome encoding approximately 2,600 proteins [12] [16]. This organism exhibited sophisticated metabolic capabilities and an early immune system, existing within an established ecological framework. From this ancestral state, a remarkable functional radiation occurred, whereby primitive biomolecules diversified to fulfill specialized roles across biochemistry. This review examines the trajectory of this radiation, with particular focus on the β-grasp fold, a structural scaffold that evolved from fundamental RNA metabolism functions in LUCA to specialized sulfur transfer systems and eventually to the complex regulatory apparatus of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins in modern eukaryotes.

Functional radiation describes the evolutionary process where a single ancestral structure or molecule diversifies into multiple forms with distinct biological functions. Unlike adaptive radiation typically observed at the organismal level, functional radiation operates at the molecular level, where protein folds and metabolic pathways are recruited for novel functions through gene duplication, divergence, and structural adaptation.

Current research indicates LUCA was a prokaryote-grade, anaerobic acetogen with a genome of at least 2.5 Mb, encoding approximately 2,600 proteins – comparable in complexity to modern prokaryotes [12]. LUCA possessed a functional CRISPR-Cas system, indicating an established evolutionary arms race with viral elements [16]. The β-grasp fold (β-GF), prototyped by modern ubiquitin, represents a prime example of molecular exaptation, where a simple structural scaffold was repeatedly recruited for novel functions throughout evolutionary history.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA)

| Feature | Reconstruction | Methodology | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ~4.2 Ga (4.09-4.33 Ga) | Divergence time analysis of pre-LUCA gene duplicates | [12] |

| Genome Size | ~2.5 Mb (2.49-2.99 Mb) | Phylogenetic reconciliation & comparative genomics | [12] |

| Proteome | ~2,600 proteins | Probabilistic gene-tree species-tree reconciliation | [12] [16] |

| Metabolism | Anaerobic acetogen with Wood-Ljungdahl pathway | Phylogenomic analysis of metabolic proteins | [12] [16] |

| Cellular Features | DNA genome, ribosomes, cell membrane, ion transporters | Universal conserved cellular machinery | [17] [16] |

| Ecological Context | Part of established ecosystem, possibly hydrothermal vents | Metabolic reconstruction & geochemical constraints | [12] [17] |

The β-Grasp Fold: A Versatile Structural Scaffold

The β-grasp fold is a compact protein domain characterized by a β-sheet with 4-5 antiparallel strands that appears to "grasp" an α-helical segment [1]. This simple yet versatile architecture serves as a structural scaffold for an extraordinary diversity of biochemical functions in modern organisms. The fold is defined by its core structural features, which provide stable surfaces for molecular interactions while accommodating extensive sequence variation.

Structural Characteristics and Functional Versatility

The manifold functional abilities of the β-grasp fold arise primarily from its prominent β-sheet, which provides an exposed surface for diverse interactions. In some cases, these sheets form open barrel-like structures that accommodate larger ligands or catalytic centers [1]. This structural plasticity has enabled the fold to be recruited for:

- Enzymatic active sites (e.g., NUDIX phosphohydrolases)

- Iron-sulfur cluster binding

- RNA, soluble ligand, and co-factor binding

- Sulfur transfer reactions

- Adaptor functions in signaling pathways

- Assembly of macromolecular complexes

- Post-translational protein modification

Systematic analysis indicates that both enzymatic activities and co-factor binding have independently evolved on at least three separate occasions within different β-grasp fold lineages, while iron-sulfur-cluster-binding emerged at least twice independently [1].

Evolutionary Trajectory: From LUCA to Modern Systems

β-Grasp Fold Lineages Already Present in LUCA

Evolutionary reconstruction indicates that by the time of LUCA, the β-grasp fold had already differentiated into at least seven distinct lineages, encompassing much of the structural diversity observed in extant versions of the fold [1]. The earliest β-grasp fold members in pre-LUCA evolution were likely involved in fundamental RNA metabolism, with subsequent radiation into various functional niches.

Table 2: Major Evolutionary Transitions in β-Grasp Fold Function

| Evolutionary Stage | Functional Innovations | Key Examples | Evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-LUCA RNA World | RNA metabolism, nucleotide binding | Primitive RNA-binding domains | Phylogenetic analysis | [1] [18] |

| LUCA Era | Diversification into 7 distinct lineages | Sulfur transfer systems (ThiS, MoaD) | Universal distribution in Archaea and Bacteria | [1] |

| Early Prokaryotic Radiation | Metabolic specialization, co-factor binding | NUDIX hydrolases, ferredoxins, SLBB domains | Lineage-specific expansions in bacteria and archaea | [1] |

| Eukaryotic Emergence | Protein modification, signaling adaptors | Ubiquitin, Ubls, adaptor domains (UBX, RA, PB1) | Domain architecture complexity increase | [1] |

The Sulfur Transfer Precursor Hypothesis

The evolutionary connection between sulfur transfer systems and ubiquitin-like protein modification represents a particularly illuminating example of functional radiation. The sulfur transfer proteins ThiS and MoaD, involved in thiamine and molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis respectively, contain β-grasp folds closely related to ubiquitin [1]. These systems share remarkable mechanistic similarities with modern ubiquitination:

- C-terminal residues form thiocarboxylates (analogous to ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine)

- Activation by enzymes (ThiF and MoeB) structurally similar to E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes

- ATP-dependent activation mechanisms

This phylogenetic and mechanistic evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that eukaryotic ubiquitin-conjugation systems evolved from more ancient bacterial precursors involved in sulfur transfer reactions for metabolite biosynthesis [1].

Experimental Approaches for Reconstruction of Ancient Functions

Phylogenomic Analysis and Tree Reconciliation

Methodology: Probabilistic gene-tree species-tree reconciliation using algorithms such as ALE (Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation) enables reconstruction of gene family evolution across deep evolutionary timescales [12].

Protocol:

- Species Tree Construction: Infer a reference species tree from universal marker genes (57 phylogenetic markers recommended) across broadly sampled archaeal and bacterial lineages [12].

- Gene Family Identification: Cluster orthologous groups using KEGG Orthology (KO) or Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) databases.

- Gene Tree Reconstruction: Generate bootstrapped phylogenetic trees for each gene family.

- Reconciliation Analysis: Compare gene trees to the species tree to infer evolutionary events (duplications, transfers, losses) using probabilistic models.

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Calculate presence probabilities for gene families at ancestral nodes, including LUCA.

Application: This approach identified 399 high-probability protein families in LUCA, with estimates of a total proteome of 2,451-2,855 proteins, indicating substantial molecular complexity [12] [16].

Universal Paralog Dating for Molecular Clock Calibration

Methodology: Divergence time estimation using pre-LUCA gene duplicates provides cross-bracing for molecular clock analyses [12].

Protocol:

- Paralog Identification: Identify protein families that duplicated before LUCA (e.g., catalytic and non-catalytic subunits of ATP synthases, elongation factors EF-Tu and EF-G) [12].

- Sequence Alignment and Tree Building: Construct phylogenetic trees for each paralogous family.

- Fossil Calibration: Apply multiple fossil calibrations (e.g., oxygenic photosynthesis evidence ~2.95 Ga) to constrain node ages.

- Cross-bracing Implementation: Use shared nodes across paralog trees to improve divergence time estimates.

- Molecular Clock Analysis: Apply relaxed clock models (GBM and ILN) to estimate divergence times with confidence intervals.

Application: This method dated LUCA to approximately 4.2 Ga (4.09-4.33 Ga), suggesting rapid evolution from life's origin to complex cellular organization [12].

Structural Phylogenetics and Fold Analysis

Methodology: Comprehensive sequence-structure analysis to identify remote homology and evolutionary relationships across diverse β-grasp fold members [1].

Protocol:

- Structure-Based Searches: Use known β-grasp fold structures as queries for similarity searches against structural databases.

- Iterative Sequence Profiling: Apply PSI-BLAST with progressively built hidden Markov models to detect distant homologs.

- Topological Analysis: Compare structural topologies and conservation of core elements.

- Functional Site Mapping: Identify conserved residues and structural motifs associated with specific functions.

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Build trees based on structural alignments to reconstruct evolutionary relationships.

Application: This approach revealed previously unrecognized β-grasp fold variants and established evolutionary connections between functionally distinct families [1].

Diagram 1: Evolutionary trajectory of β-grasp fold functions from LUCA to modern systems

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying β-Grasp Fold Evolution and Function

| Reagent/Method | Specific Application | Function/Utility | Example Use Case | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALE Software | Phylogenetic reconciliation | Infers gene family evolution events (duplication, transfer, loss) | Reconstructing LUCA gene content | [12] |

| PSI-BLAST | Remote homology detection | Identifies distantly related protein sequences | Finding novel β-grasp fold members | [1] |

| Molecular Clock Calibration (Universal Paralogs) | Deep evolutionary dating | Provides cross-bracing for divergence time estimates | Dating LUCA with pre-LUCA duplicates | [12] |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Ancient immunity study | Models early host-viral coevolution | Understanding LUCA's defense mechanisms | [12] [16] |

| Twister Ribozymes | RNA world reconstruction | Molecular fossils of early RNA catalysis | Studying pre-LUCA RNA replication | [18] |

| Single-Molecule Techniques (Magnetic Tweezers) | Enzyme mechanism analysis | Characterizes low-probability catalytic events | Studying error-prone RNA polymerases | [18] |

| Structural Phylogenetics | Fold evolution mapping | Establishes evolutionary relationships based on structure | Connecting ubiquitin to sulfur transfer proteins | [1] |

The functional radiation from LUCA represents a fundamental evolutionary process whereby limited molecular components diversified to create biochemical complexity. The β-grasp fold exemplifies this phenomenon, evolving from fundamental RNA metabolism and sulfur transfer functions in LUCA to the sophisticated regulatory systems of modern eukaryotes. This trajectory underscores how ancient metabolic systems can be co-opted for novel signaling and regulatory functions through evolutionary processes.

Future research should focus on: (1) experimental reconstruction of ancestral β-grasp fold proteins to test functional predictions; (2) exploration of potential ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in extant bacteria and archaea; and (3) investigation of how structural plasticity enables functional radiation at the molecular level. Understanding these evolutionary principles provides not only insights into life's history but also frameworks for engineering novel protein functions for therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

Diversification in Prokaryotes vs. UBL Expansion in Eukaryotes

The β-grasp fold (β-GF) is a compact protein structural scaffold characterized by a β-sheet with five anti-parallel strands that appears to "grasp" a single α-helical segment [1] [11]. This ancient fold serves as a remarkable example of evolutionary recruitment, having been utilized for a strikingly diverse range of biochemical functions across all domains of life. While this fold is prototyped by eukaryotic ubiquitin (Ub), its evolutionary history reveals a fundamental divergence in adaptive strategies between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Research indicates that prokaryotes primarily exploited this fold for structural and functional diversification, leading to its incorporation into various enzymatic and metabolic pathways. In contrast, eukaryotes leveraged this scaffold for a massive expansion of ubiquitin-like protein (UBL) modifiers that regulate cellular physiology through reversible post-translational modifications [1] [19] [11]. This whitepaper examines the comparative evolutionary trajectories of the β-grasp fold in prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems, with implications for understanding fundamental biological mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Structural Hallmarks and Functional Versatility of the β-Grasp Fold

Core Structural Features

The β-grasp fold comprises several conserved structural elements that contribute to its stability and functional versatility:

- A β-sheet with five anti-parallel strands that forms the core structural scaffold

- A single α-helical segment positioned adjacent to and "grasped" by the β-sheet

- Potential for diverse loop regions and insertions that enable functional specialization

- A compact globular structure that provides a stable platform for molecular interactions [1] [11] [20]

The fold's remarkable functional plasticity arises from its ability to present diverse interaction surfaces, particularly through the prominent β-sheet, which provides an exposed platform for binding various biomolecules or forming open barrel-like structures [1].

Functional Versatility of the Fold

The β-grasp fold has been recruited for an extraordinary diversity of biological functions, including:

Table 1: Functional Diversity of β-Grasp Fold Proteins

| Function Category | Specific Examples | Organismic Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Post-translational modification | Ubiquitin, SUMO, NEDD8 | Primarily eukaryotic |

| Enzymatic activities | NUDIX phosphohydrolases, staphylokinases | Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic |

| Cofactor binding/scaffolding | Iron-sulfur clusters, molybdopterin | Primarily prokaryotic |

| RNA/soluble ligand binding | TGS domain, SLBB domain, vitamin B12 binding | Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic |

| Sulfur transfer | ThiS, MoaD in thiamine and molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis | Primarily prokaryotic |

| Adaptor functions | RA, PB1, FERM N-terminal domains | Primarily eukaryotic |

| Toxin activities | Staphylococcal enterotoxin B, superantigens | Primarily prokaryotic |

This functional diversity emerged early in evolution, with the β-grasp fold already having differentiated into at least seven distinct lineages by the time of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all extant organisms [1].

Prokaryotic Diversification: Functional and Structural Radiation

Early Evolutionary Radiation in Prokaryotes

Comparative genomic analyses reveal that the most extensive structural and functional diversification of the β-grasp fold occurred in prokaryotes. By the time of LUCA, the fold had already differentiated into multiple distinct lineages that encompassed much of the structural diversity observed in extant versions [1] [11]. The earliest β-grasp fold members were likely involved in RNA metabolism and translation-related RNA interactions, as evidenced by the TGS domain found in aminoacyl tRNA synthetases and other translation regulators [1].

This prokaryotic diversification led to the incorporation of the fold into various metabolic pathways, particularly those involving sulfur transfer and cofactor biosynthesis. Key examples include:

- ThiS: Involved in thiamine biosynthesis, forms a thiocarboxylate at its C-terminus for sulfur transfer

- MoaD: Participates in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis, similarly employs a C-terminal thiocarboxylate

- Iron-sulfur cluster scaffolding: β-grasp fold proteins serve as scaffolds for iron-sulfur clusters in ferredoxins [1] [21] [22]

Enzymatic Recruitment and Novel Functions

Prokaryotes extensively recruited the β-grasp fold for diverse enzymatic functions, with both enzymatic activities and cofactor-binding having independently evolved on multiple occasions [1]. Notable examples include:

- NUDIX phosphohydrolases: Utilize the β-grasp fold as a scaffold for catalytic activities against diverse substrates

- Staphylokinases and streptokinases: Fibrinolytic enzymes in low GC Gram-positive bacteria

- TmoB: A subunit of the aromatic monooxygenase oxygenase complex with structurally conserved β-grasp fold

- RnfH: A component of Rnf dehydrogenases utilizing the fold for structural integrity [1] [11]

Table 2: Key Prokaryotic β-Grasp Fold Proteins and Their Functions

| Protein/Domain | Function | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|

| ThiS | Sulfur carrier in thiamine biosynthesis | Forms thiocarboxylate, activated by ThiF (E1-like) |

| MoaD | Sulfur carrier in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis | Forms thiocarboxylate, activated by MoeB (E1-like) |

| TGS domain | RNA binding | Found in aminoacyl tRNA synthetases, translation regulators |

| YukD | Unknown function | Conserved in Bacillus subtilis and related bacteria |

| SLBB domain | Soluble ligand binding | Binds vitamin B12 and other solutes |

| β-grasp ferredoxin | Iron-sulfur cluster binding | Metal chelation via cysteine-containing flaps |

Prokaryotic Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Systems

Despite the absence of canonical ubiquitin in prokaryotes, several ubiquitin-like modification systems have been identified:

- Pup (prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein): An intrinsically disordered protein in actinobacteria that targets proteins for proteasomal degradation through conjugation (pupylation) [21] [23]

- SAMP (small archaeal modifier proteins): Ub-fold proteins in archaea that form isopeptide bonds with target proteins (sampylation) [21]

- TtuB: Ub-fold protein in Thermus species involved in both protein modification and sulfur-transfer pathways [21]

These systems represent evolutionary innovations that parallel eukaryotic ubiquitination but employ distinct mechanisms and enzymes. The pupylation system, for instance, utilizes a single ligase (PafA) and depupylase (Dop) rather than the multi-enzyme cascade characteristic of eukaryotic ubiquitination [23].

Eukaryotic Expansion: The Ubiquitin-Like Protein Explosion

Massive Diversification of UBL Modifiers

The eukaryotic phase of β-grasp fold evolution was predominantly characterized by a dramatic expansion of ubiquitin-like proteins, with at least 70 distinct UBL families distributed across eukaryotes [19] [11]. Genomic evidence indicates that nearly 20 UBL families were already present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor, including:

- Multiple protein-conjugated forms (Ub, SUMO, NEDD8, URM1, Apg12)

- Lipid-conjugated forms (ATG8)

- Versions functioning as adaptor domains in multi-module polypeptides [1] [19] [11]

This expansion was accompanied by an increase in domain architectural complexity, with UBL domains incorporated into numerous proteins as adaptors in various signaling contexts [1].

The Ubiquitin Signaling System

The eukaryotic ubiquitin system represents one of the most elaborate manifestations of the β-grasp fold, characterized by:

- A conserved three-enzyme cascade (E1-E2-E3) for conjugation

- A dedicated system for deconjugation by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs)

- Specialized recognition receptors for ubiquitin signals

- The capacity to form diverse chain architectures through different lysine linkages [1] [20]

The different types of ubiquitin modifications create a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that regulates practically all aspects of eukaryotic biology, from protein degradation to DNA repair, signaling transduction, and immune responses [20].

Functional Specialization of UBL Families

The expansion of UBL families in eukaryotes enabled functional specialization and compartmentalization:

Table 3: Major Eukaryotic UBL Families and Their Functions

| UBL Family | Primary Functions | Conjugation System |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin | Protein degradation, DNA repair, signaling, endocytosis | E1-E2-E3 cascade |

| SUMO | Nuclear transport, transcriptional regulation, DNA repair | E1-E2-E3 cascade |

| NEDD8 | Regulation of cullin-RING ligases, cell signaling | E1-E2-E3 cascade |

| Apg12 | Autophagy, vesicle trafficking | E1-E2-like system |

| ATG8 | Autophagy, membrane dynamics | E1-E2-like system |

| ISG15 | Immune response, antiviral defense | E1-E2-E3 cascade |

| UFM1 | ER stress response, development | E1-E2-E3 cascade |

| Urm1 | tRNA thiolation, oxidative stress response | E1-like enzyme |

The early diversification of UBL families played a major role in the emergence of characteristic eukaryotic cellular systems, including nucleo-cytoplasmic compartmentalization, vesicular trafficking, lysosomal targeting, protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, and chromatin dynamics [19] [11].

Evolutionary Relationships and Transitional Systems

Evolutionary Origins of Eukaryotic UBL Systems

Recent comparative genomics indicates that precursors of the eukaryotic Ub-system were already present in prokaryotes [11] [22]. The simplest versions combine a Ubl and an E1-like enzyme involved in metabolic pathways related to metallopterin, thiamine, cysteine, siderophore, and modified base biosynthesis [11]. Key evolutionary connections include:

- ThiS/MoaD in prokaryotes are closely related to eukaryotic URM1

- ThiF/MoeB enzymes are structural and functional analogs of eukaryotic E1 enzymes

- Similar mechanisms of C-terminal adenylation and sulfur transfer through thiocarboxylate formation [11] [22]

These systems appear to have been recruited in eukaryotes for protein modification, with sampylation in archaea and urmylation in eukaryotes representing direct recruitment of such systems as simple protein-tagging apparatuses [11].

Transitional Systems Bridging the Functional Gap

Several systems represent evolutionary transitions between sulfur carrier and protein modifier functions:

- Urm1: Functions as both a sulfur carrier in tRNA thiolation and a protein modifier in response to oxidative stress

- SAMPs: Archaeal modifiers that function in both sulfur transfer and protein modification, with SAMP2 capable of forming poly-samp chains analogous to polyubiquitin

- TtuB: Functions in both protein modification and tRNA thiolation in Thermus species [21] [11]

These dual-function systems provide fascinating insights into how the eukaryotic ubiquitination system may have evolved from more ancient metabolic sulfur-transfer systems [11].

The following diagram illustrates the evolutionary relationships and functional transitions between prokaryotic and eukaryotic β-grasp fold systems:

Figure 1: Evolutionary Transitions of β-Grasp Fold Function

Experimental Approaches and Research Tools

Key Methodologies for Studying β-Grasp Fold Evolution

Research into the evolution and diversification of β-grasp fold proteins employs several sophisticated methodologies:

Comparative Genomic Analysis

- Sequence profile searches: Using tools like PSI-BLAST to identify distant homologs through iterative searches [1] [22]

- Domain architecture analysis: Examining gene neighborhoods and domain fusions to infer functional relationships [22]

- Phylogenetic profiling: Reconstructing evolutionary relationships across diverse taxa [1]

Structural Analysis

- Structural similarity clustering: Using programs like DALI to calculate pairwise structural alignment Z-scores [22]

- Topological similarity assessment: Identifying structurally conserved regions despite sequence divergence [1]

- Fold recognition: Detecting remote homologs through structural rather than sequence similarity [1]

Functional Characterization

- Enzyme activity assays: Measuring adenylation, conjugation, and deconjugation activities [21] [23]

- Interaction studies: Using bacterial two-hybrid systems, pull-down assays, and co-expression studies [21]

- Mass spectrometry: Identifying covalent modifications and chain architectures [21] [20]

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The following table outlines key reagents and methodologies essential for research in this field:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for β-Grasp Fold Studies

| Reagent/Methodology | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| PSI-BLAST | Detection of distant homologs through sequence profile searches | Iterative search strategy, sensitive for remote homology detection |

| DALI Server | Structural comparison and fold recognition | Z-score based structural alignment, database scanning |

| Tandem Mass Spectrometry | Identification of covalent modifications (ubiquitination, pupylation) | Detection of isopeptide linkages, chain architecture determination |

| Bacterial Two-Hybrid System | Protein-protein interaction screening | Particularly useful for identifying prokaryotic interaction networks |

| JAB Domain Proteases | Deconjugation enzyme tools | Study of ubiquitin/UBL removal mechanisms, conservation from prokaryotes to eukaryotes |

| E1-like Adenylating Enzymes | Activation of UBLs for conjugation | Study of initial activation step, conservation across domains of life |

| Polyclonal Anti-Ub/UBL Antibodies | Detection of modified proteins in cellular contexts | Specific recognition of modifier proteins and their conjugates |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The comparative analysis of β-grasp fold evolution between prokaryotes and eukaryotes reveals fundamental principles of molecular evolution, including:

- How simple structural scaffolds can be recruited for diverse functions

- How metabolic systems can evolve into sophisticated signaling pathways

- How domain architecture complexity contributes to functional innovation

From a therapeutic perspective, understanding these evolutionary relationships provides valuable insights for:

- Antibiotic development: Targeting bacterial-specific ubiquitin-like systems such as pupylation in Mycobacteria [23]

- Cancer therapeutics: Exploiting the ubiquitin-proteasome system for targeted protein degradation

- Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases: Modulating ubiquitin-like signaling pathways in immune regulation

Future research directions should focus on:

- Characterizing the numerous uncharacterized β-grasp fold proteins identified in genomic studies

- Elucidating the structural determinants of functional specificity within this fold family

- Developing chemical probes that selectively target specific ubiquitin-like modification pathways

- Exploring the therapeutic potential of modulating prokaryotic ubiquitin-like systems for antimicrobial applications

The evolutionary journey of the β-grasp fold from simple prokaryotic metabolic functions to sophisticated eukaryotic signaling systems exemplifies how nature creatively reuses successful structural templates, providing both fundamental biological insights and practical therapeutic opportunities.

Techniques for Probing Structure, Dynamics, and Drug Discovery Applications

The β-grasp fold is a widespread and evolutionarily ancient protein structural motif characterized by a β-sheet, typically composed of four or five strands, that wraps around a single α-helix [1] [2]. This compact fold serves as a versatile structural scaffold that has been recruited for a strikingly diverse range of biochemical functions throughout evolution. Its most renowned representatives are ubiquitin (UB) and the family of ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs), which include well-characterized members such as NEDD8, SUMO, and Ufm1 [1] [24] [25]. Despite their low sequence identity—for instance, only 14% between Ufm1 and ubiquitin—these proteins share this conserved tertiary structure [24]. The functional versatility of the β-grasp fold arises primarily from its prominent β-sheet, which provides an exposed surface for diverse interactions, and its ability to form open barrel-like structures, enabling roles in enzyme active sites, binding of iron-sulfur clusters, RNA-soluble-ligand and co-factor-binding, sulfur transfer, and critical adaptor functions in signaling and post-translational modification [1]. The structural elucidation of UBLs is therefore not merely an exercise in structure determination but a fundamental prerequisite for understanding their vast functional roles in cellular regulation, disease mechanisms, and potential therapeutic targeting.

The β-Grasp Fold: A Versatile Structural Scaffold

Core Structural Features and Functional Diversity

The canonical β-grasp fold, as prototyped by ubiquitin, consists of a mixed β-sheet with five anti-parallel strands and a single α-helix that is grasped by the sheet [1]. This core structure is both stable and malleable, allowing for significant topological variations and elaborations that underlie its functional adaptability. Systematic analyses have revealed that by the time of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), the β-grasp fold had already differentiated into at least seven distinct lineages, encompassing much of the structural diversity seen today [1].

The table below summarizes major functional classes of β-grasp fold proteins and their representative members.

Table 1: Functional Diversity of the β-Grasp Fold

| Functional Class | Representative Members | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Post-translational Protein Modifiers | Ubiquitin, NEDD8, SUMO, Ufm1, Apg12 | Covalent modification of target proteins to regulate stability, activity, or localization [1] [24]. |

| Enzymatic Scaffolds | MutT/Nudix phosphohydrolases | Provide a scaffold for enzymatic active sites [1]. |

| Co-factor Binding Proteins | 2Fe-2S Ferredoxins, PduS | Bind iron-sulfur clusters or other co-factors [1] [2]. |

| Soluble Ligand Binders | Transcobalamin, SLBB Superfamily | Bind small molecules like vitamin B12 [2]. |

| RNA Binding Proteins | TGS Domain | Mediate RNA-protein interactions [1]. |

| Protein-Protein Interaction Adaptors | RA, PB1, FERM domains | Act as adaptors in signaling complexes [1]. |

| Toxins & Superantigens | Staphylococcal enterotoxin B | Mediate toxic shock syndrome [1]. |

A key evolutionary innovation within this fold is the ubiquitin superfamily. In eukaryotes, this family diversified into at least 67 distinct families, with 19–20 families already present in the eukaryotic common ancestor [1]. This expansion was coupled with a dramatic increase in domain architectural complexity, facilitating the sophisticated regulatory networks that are characteristic of eukaryotic cells.

Structural Variations and Ligand Binding

The core β-grasp fold is often embellished with secondary structure inserts that confer functional specificity. A prime example is the Soluble-Ligand-Binding β-grasp (SLBB) superfamily. Members of this superfamily, such as the C-terminal domain of transcobalamin (a vitamin B12 uptake protein), are characterized by the insertion of a β-hairpin after the core α-helix [2]. This insert plays a prominent role in contacting the soluble ligand, with additional interactions contributed by residues from the core β-sheet itself. This demonstrates how the robust core scaffold can be adapted through localized elaborations to generate novel ligand-binding surfaces [2].

Principles of Structure Determination for UBLs