UBB and UBC: Decoding Polyubiquitin Gene Organization, Regulation, and Therapeutic Targeting

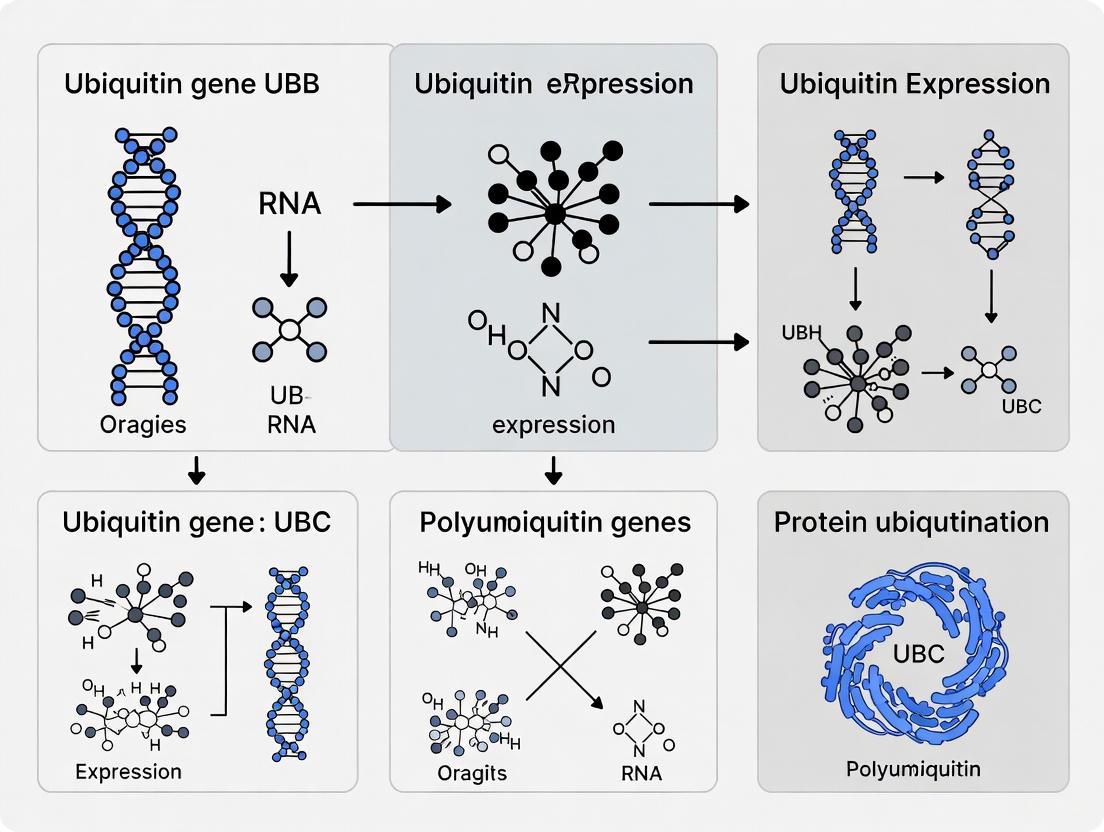

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the polyubiquitin genes UBB and UBC, which are critical for maintaining cellular ubiquitin homeostasis.

UBB and UBC: Decoding Polyubiquitin Gene Organization, Regulation, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the polyubiquitin genes UBB and UBC, which are critical for maintaining cellular ubiquitin homeostasis. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental organization and expression of these genes, their indispensable roles in embryonic development and stress response, and the severe consequences of their disruption. The content further delves into advanced methodologies for studying ubiquitin pools, discusses common challenges in experimental models, and validates findings through comparative analysis of gene function and emerging therapeutic strategies that target the ubiquitin system for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

The Genomic Blueprint: Unraveling the Structure and Basal Regulation of UBB and UBC Genes

Ubiquitin is a small, highly conserved regulatory protein found in most eukaryotic tissues and is integral to numerous cellular processes, including protein degradation, DNA repair, and cell signaling [1]. The human genome contains four genes that encode ubiquitin: UBB, UBC, UBA52, and RPS27A [1] [2]. These genes produce ubiquitin through two primary types of precursors:

- Ribosomal fusion proteins: UBA52 and RPS27A encode single ubiquitin molecules fused to the ribosomal proteins L40 and S27a, respectively [2] [1].

- Polyubiquitin precursor proteins: UBB and UBC genes code for precursor proteins consisting of exact head-to-tail repeats of ubiquitin [1] [3].

The covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins, a process known as ubiquitylation (or ubiquitination), is a key post-translational modification that can mark proteins for degradation by the proteasome, alter their cellular location, affect their activity, and promote or prevent protein interactions [1].

Gene-Specific Structures and Functions

UBA52

The UBA52 gene encodes a fusion protein consisting of ubiquitin at the N-terminus and the ribosomal protein L40 at the C-terminus [2]. This structure is sometimes referred to as ubiquitin carboxyl extension protein 52. The gene is also known by several aliases, including HUBCEP52, RPL40, and UBCEP2 [2]. After translation, the ubiquitin and L40 moieties are processed to generate free ubiquitin and the functional ribosomal protein.

RPS27A

The RPS27A gene encodes a fusion protein similar to UBA52, where a single ubiquitin moiety is fused to the ribosomal protein S27a [1]. It is also known as UBA80. Like UBA52, this fusion protein is post-translationally processed to release free ubiquitin and the mature ribosomal protein S27a, which is then incorporated into the ribosome.

UBB

The UBB gene encodes a polyubiquitin precursor protein, though the exact number of ubiquitin repeats in the human UBB protein is not specified in the search results. This gene belongs to one of the two stress-regulated polyubiquitin genes in mammals (along with UBC) and plays a crucial role in maintaining cellular ubiquitin levels under stress conditions [3].

UBC

The UBC gene encodes the polyubiquitin-C precursor protein and is located on chromosome 12q24.31 [3]. The gene consists of two exons, and its promoter contains putative heat shock elements (HSEs) that mediate induction upon cellular stress. The UBC gene contains a series of nine to ten ubiquitin coding units in a head-to-tail arrangement [3]. Upon translation, these polyubiquitin precursors are cleaved by deubiquitinating enzymes to release multiple free ubiquitin monomers.

Table 1: Characteristics of Human Ubiquitin Genes

| Gene Name | Encoded Product Type | Fused Component | Key Aliases | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBA52 | Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein fusion | Ribosomal protein L40 | HUBCEP52, RPL40, UBCEP2 | Source of ubiquitin and ribosomal protein L40 |

| RPS27A | Ubiquitin-ribosomal protein fusion | Ribosomal protein S27a | UBA80 | Source of ubiquitin and ribosomal protein S27a |

| UBB | Polyubiquitin precursor | Head-to-tail ubiquitin repeats | - | Maintains ubiquitin levels under stress |

| UBC | Polyubiquitin precursor | Head-to-tail ubiquitin repeats (9-10 units) | - | Primary stress-induced ubiquitin source |

Quantitative Analysis of Ubiquitin Gene Properties

Table 2: Molecular and Functional Properties of Ubiquitin Genes

| Property | UBA52 | RPS27A | UBB | UBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin copies in precursor | 1 | 1 | Multiple repeats (exact number unspecified) | 9-10 repeats |

| Chromosomal location | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 12q24.31 |

| Response to stress | Not specified | Not specified | Stress-regulated | Stress-regulated (via HSEs in promoter) |

| Essentiality | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Embryonic lethal when homozygously deleted in mice |

| Key functions | Ubiquitin source, ribosome biogenesis | Ubiquitin source, ribosome biogenesis | Ubiquitin pool maintenance | Ubiquitin pool maintenance, stress response |

The Ubiquitination Pathway: Mechanism and Enzymology

The process of ubiquitin conjugation to target proteins involves a sequential enzymatic cascade [1]:

Ubiquitin Enzymatic Cascade

Step 1: Activation

Ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1) initiate the cascade in an ATP-dependent process. E1 first catalyzes the adenylation of the C-terminus of ubiquitin, then forms a thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [1]. The human genome contains two genes that produce E1 enzymes: UBA1 and UBA6 [1].

Step 2: Conjugation

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2) then accept the activated ubiquitin from E1 through a trans(thio)esterification reaction, forming a thioester bond with their own active-site cysteine residues [1]. Humans possess 35 different E2 enzymes, each characterized by a highly conserved ubiquitin-conjugating catalytic (UBC) fold [1].

Step 3: Ligation

Ubiquitin ligases (E3) catalyze the final transfer of ubiquitin to the target protein. E3 enzymes function as substrate recognition modules and can be categorized based on their domains:

- HECT domain E3s: Form a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate

- RING domain E3s: Catalyze direct transfer from the E2 enzyme to the substrate [1]

The human genome encodes hundreds of E3 ligases, which provide specificity to the ubiquitination system by recognizing particular target proteins. Multi-subunit E3 complexes, such as the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) and the SCF complex (Skp1-Cullin-F-box protein complex), are examples of sophisticated recognition machinery [1].

Experimental Analysis of Ubiquitin Function

Systematic Mutagenesis to Study Ubiquitin-E1 Interaction

A high-throughput reverse engineering strategy has been developed to analyze how ubiquitin mutations impact network function [4]. This approach systematically examines all point mutations in ubiquitin and their effects on E1 activation and yeast growth rate:

Ubiquitin Mutagenesis Analysis Workflow

Detailed Methodology

Library Construction and Yeast Display:

- Create comprehensive site saturation libraries of ubiquitin point mutations in eight pools of 9-10 consecutive amino acid positions [4].

- Transfer mutant libraries to a yeast display system that presents ubiquitin molecules with a free C-terminus, which is essential for E1 activation.

- Use short read sequencing to efficiently interrogate the mutated regions.

E1 Reactivity Assay:

- Incubate display cells with limiting concentrations of yeast E1 enzyme (Uba1).

- Label cells with fluorescent antibodies targeted to E1 and an HA epitope to assess display efficiency.

- Use flow cytometry to separate cells into pools of E1-reactive cells and control HA-displaying cells.

- Recover plasmids encoding the mutated ubiquitin library from sorted cells.

- Sequence the mutated region and analyze differences in mutant frequency between E1-reactive cells and control cells to assess effects of each point mutation on E1 reactivity.

Validation with Purified Proteins:

- Develop an independent assay using purified proteins to measure E1 reactivity of individual mutants relative to wild-type ubiquitin.

- Compare results from yeast display system with purified protein assays to validate findings.

This systematic approach revealed that most ubiquitin mutations that disrupt E1 activation also impair yeast growth rate, indicating that these mutations typically affect multiple ubiquitin functions beyond just E1 interaction [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin System Investigation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Site saturation mutagenesis libraries | Systematic analysis of all possible point mutations in ubiquitin | Mapping functional residues critical for E1 binding and activation [4] |

| Yeast display system | Surface expression of ubiquitin variants with free C-terminus | High-throughput screening of ubiquitin mutants for E1 reactivity [4] |

| Recombinant E1, E2, E3 enzymes | In vitro reconstitution of ubiquitination cascade | Biochemical characterization of ubiquitin transfer mechanisms [1] |

| Fluorescent antibody labeling | Detection and sorting of cells displaying specific epitopes | Flow cytometry separation of E1-reactive ubiquitin mutants [4] |

| Deep sequencing platforms | High-throughput analysis of mutant populations | Identification and quantification of ubiquitin mutants from sorted cells [4] |

| PROTAC molecules | Targeted protein degradation via ubiquitin-proteasome system | Therapeutic application of ubiquitin ligase recruitment [5] |

Therapeutic Applications and Research Frontiers

PROTAC Technology

PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) are innovative trimeric small molecules that consist of:

- A target protein-binding ligand

- An E3 ubiquitin ligase-recruiting ligand

- A linker connecting these two moieties [5]

PROTACs work by bringing the target protein into proximity with an E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the target protein by the proteasome [5]. This technology represents a powerful application of ubiquitin system knowledge for therapeutic purposes. Currently, more than 80 PROTAC drugs are in development pipelines, with over 100 commercial organizations involved in this research area [5].

While most current PROTACs utilize one of four E3 ligases (cereblon, VHL, MDM2, and IAP), research is expanding to incorporate other E3 ligases such as DCAF16, DCAF15, DCAF11, KEAP1, and FEM1B to broaden the scope of targetable proteins [5].

Advanced PROTAC Developments

Recent innovations in PROTAC technology include:

Pro-PROTACs (PROTAC prodrugs):

- Designed to control delivery of PROTAC molecules and achieve required on-target exposure

- Protected with labile groups that can be selectively removed under specific physiological conditions

- Enhance precision targeting and reduce off-target effects [5]

Opto-PROTACs (photocaged PROTACs):

- Incorporate photolabile groups (e.g., 4,5-dimethoxy-2-nitrobenzyl moiety) that prevent E3 ligase binding

- Activated by specific wavelength light to release functional PROTACs

- Enable spatiotemporal control of protein degradation [5]

As of 2025, there are over 30 PROTAC candidates in clinical trials, including 19 in Phase I, 12 in Phase II, and 3 in Phase III, targeting proteins such as androgen receptor (AR), estrogen receptor (ER), STAT3, BTK, and IRAK4 [5].

Evolutionary Context and Biological Significance

The ubiquitin system has deep evolutionary roots. The characteristic beta-grasp fold of ubiquitin is also found in prokaryotic proteins involved in sulfur transfer, such as ThiS and MoaD, which function in thiamine and molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis [6]. This suggests that the eukaryotic ubiquitin conjugation system evolved from more ancient metabolic enzymes.

The four ubiquitin genes in humans represent two distinct evolutionary strategies for maintaining cellular ubiquitin levels: the ribosomal fusion proteins (UBA52 and RPS27A) and the stress-inducible polyubiquitin genes (UBB and UBC) [3]. This gene organization allows for both constitutive production of ubiquitin for basal cellular functions and rapid upregulation during stress responses when increased protein degradation and recycling are required.

The essential nature of the ubiquitin system is highlighted by the embryonic lethality observed in homozygous UBC knockout mice, demonstrating the critical importance of maintaining adequate ubiquitin levels for proper fetal development and cellular stress response [3].

Ubiquitin is a 76-amino-acid protein that is one of the most evolutionarily conserved proteins known in eukaryotes [7] [8]. It plays a fundamental role in cellular physiology by targeting cellular proteins for degradation via the 26S proteasome through the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) [9] [7]. The UPS is a crucial pathway for maintaining cellular homeostasis, regulating the degradation of over 80% of cellular proteins, including short-lived, misfolded, and damaged proteins [9]. Beyond proteolysis, ubiquitination is involved in nearly all eukaryotic life activities, including cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, kinase signaling, and the stress response [9] [3].

In humans, ubiquitin is encoded by a multigene family where all genes encode fusion proteins that require proteolytic processing to release mature ubiquitin monomers [3] [8]. The ubiquitin genes include two stress-regulated polyubiquitin genes, UBB (Ubiquitin B) and UBC (Ubiquitin C), along with two ubiquitin-ribosomal fusion genes, UBA52 and RPS27A [3]. This review focuses specifically on the structural organization, functional significance, and research methodologies pertaining to the tandem ubiquitin repeats within the UBB and UBC polyubiquitin genes, framing this discussion within broader research on ubiquitin gene organization.

Structural Organization of UBB and UBC Genes

Genomic Architecture and Repeat Variation

The UBB and UBC genes exhibit a unique genomic structure characterized by head-to-tail tandem repeats of the ubiquitin coding sequence without spacer regions [10] [7]. This organization results in the translation of polyubiquitin precursor proteins that are subsequently cleaved by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) to yield monomeric ubiquitin [11].

Table 1: Structural Characteristics of Human Polyubiquitin Genes

| Gene | Chromosomal Location | Exon Count | Ubiquitin Repeat Number | Gene Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBB | 17p11.2 [7] | 5 [7] | 3 (constant in humans and great apes) [10] | High (conserved repeat number) [10] |

| UBC | 12q24.31 [3] | 2 [3] | 6-11 in humans; variable across great apes [10] | Moderate (shows lineage-specific homogenization) [10] |

The UBB gene maintains a constant repeat number of 3 ubiquitin units in humans and great apes, suggesting strong selective pressure to maintain this structure [10]. In contrast, the UBC gene exhibits significant variation in repeat number, ranging from 6 to 11 repeats in humans, with similar variability observed across great ape species including chimpanzees (10-12 repeats), gorillas (8 repeats), and orangutans (10 repeats) [10]. This heterogeneity in UBC repeat number between closely related hominoid species suggests that lineage-specific unequal crossing-over and/or gene duplication events have occurred during evolution [10].

Transcriptional Regulation and Expression Patterns

The UBB and UBC genes display distinct expression patterns and regulatory mechanisms. Both are stress-inducible polyubiquitin genes, but they differ in their basal expression and induction profiles [3]. The UBC gene promoter contains putative heat shock elements (HSEs) that mediate its induction upon cellular stress [3]. Transcription of UBC is significantly induced during various stress conditions, providing the extra ubiquitin necessary to remove damaged or unfolded proteins [3].

Table 2: Expression and Functional Profiles of Human Polyubiquitin Genes

| Characteristic | UBB | UBC |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Expression | Ubiquitous expression in tissues including liver (RPKM 498.1) and testis (RPKM 495.1) [7] | Not specifically quantified in results but described as stress-induced [3] |

| Stress Response | Stress-regulated [3] | Strongly stress-induced via HSEs in promoter [3] |

| Biological Functions | Protein degradation, chromatin structure maintenance, gene expression regulation, stress response [7] | Sustaining heat-shock response, innate immunity, DNA repair, kinase regulation [3] |

| Phenotype of Knockout | Not specified in results | Mid-gestation embryonic lethality in homozygotes [3] |

The preservation of two stress-regulated polyubiquitin genes with different repeat numbers and variation patterns suggests complementary biological roles. While UBB maintains a stable repeat structure, UBC's variability may represent an evolutionary adaptation to diverse environmental challenges [10] [11].

Functional Significance of Tandem Repeat Organization

Advantages of Polyubiquitin Gene Structure

The tandem repeat organization of polyubiquitin genes provides several functional advantages for cellular physiology:

Rapid Ubiquitin Production Under Stress: The multi-unit structure enables cells to rapidly produce large amounts of ubiquitin needed to respond to sudden stress conditions [11]. This is particularly important during heat stress, which induces protein misfolding and aggregation, requiring rapid clearance of damaged proteins [11].

Co-regulated Expression: The polycistronic nature allows multiple ubiquitin units to be produced from a single transcriptional event, ensuring stoichiometric production of ubiquitin monomers without requiring coordinated expression of multiple genes [11] [8].

Evolutionary Flexibility: The variable repeat number in UBC represents an elegant alternative to gene copy number variation, allowing tuning of UPS activity and cellular survival during different stress conditions [11]. Natural variation in repeat numbers may optimize survival chances under various stress types.

Repeat Number and Proteostasis Regulation

Research in yeast models has demonstrated that the number of ubiquitin units in the polyubiquitin gene directly influences cellular proteostasis. The ubiquitin repeat number affects:

- Cellular Survival Rates: Following heat stress, survival rates show a dependence on ubiquitin repeat number, with both insufficient and excessive repeats reducing viability [11].

- UPS-Mediated Degradation Kinetics: The rate of ubiquitin-proteasome system-mediated proteolysis during heat stress depends on the number of ubiquitin repeats [11].

- Stress-Specific Optimization: Different repeat numbers are optimal under different types of stress, indicating that natural variation may provide adaptive advantages in fluctuating environments [11].

In mammalian systems, the essential nature of UBC is demonstrated by the mid-gestation embryonic lethality observed in homozygous UBC knockout mice, which display defects in fetal liver development, delayed cell-cycle progression, and increased susceptibility to cellular stress [3]. Heterozygous deletion with loss of a single UBC allele shows no apparent phenotype, indicating that one functional copy is sufficient under normal conditions [3].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Polyubiquitin Genes

Methodologies for Analyzing Repeat Number and Expression

Genomic Analysis Techniques

- PCR Amplification and Southern Blotting: To determine UBI4 repeat number in natural yeast strains, researchers PCR-amplified the gene and used Southern blot analysis to resolve exact gene size and rule out slippage events during PCR amplification [11]. This approach revealed remarkable variability in ubiquitin-coding units across the Saccharomyces genus.

- Sequence Analysis and Phylogenetic Comparison: Determination of nucleotide sequences for UbB and UbC across species (human, chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan) allows analysis of lineage-specific homogenization and evolutionary patterns [10]. This method identified significant differences in the homogenization of ubiquitin coding units between species.

Functional Characterization Methods

- Viability Assays Under Stress: Measurement of survival rates after sudden temperature shifts (e.g., from 30°C to 43-44°C) evaluates the functional impact of repeat number variation [11]. This approach demonstrated that strains with shorter UBI4 alleles (2 or 3 units) have significantly lower survival rates than those with longer alleles (4 or 5 units) after heat stress.

- Isogenic Strain Construction: Generation of isogenic variants that differ only in UBI4 repeat number controls for genetic background effects when evaluating the functional consequences of repeat variation [11]. This method provided direct evidence that the number of ubiquitin moieties synthesized from UBI4 influences cell survival following heat shock.

- Mono-ubiquitin Copy Number Variants: Replacement of the UBI4 gene with one or multiple copies of a single ubiquitin moiety, each controlled by its own promoter, tests whether observed phenotypes result from dose-dependent effects of multiple units [11].

Splicing Analysis and Dual-Specific Splice Sites

The unusual gene architecture of polyubiquitin genes includes specialized splicing mechanisms:

Diagram Title: DSS-mediated Splicing in Polyubiquitin Genes

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs) have been developed to test the ability of sequences within genes to function as 5' or 3' splice sites [12]. These assays involve:

- Library Construction: Extraction of successive 150-nucleotide windows tiled by 20-nucleotide increments across genes of interest, cloned into splicing reporter vectors [12].

- Efficiency Measurement: Splicing efficiencies measured as enrichment scores (log10 ratios of relative representation of spliced product in output normalized by parent species in input library) [12].

- Validation: RT-PCR detection of low-level transcript isoforms using unannotated splice sites identified by MPRA [12].

A notable feature discovered in the human UBC gene is the presence of dual-specific splice sites (DSSs) containing the AGGT motif that can function as either 5' or 3' splice sites [12]. These DSSs are arranged in a tandem array that precisely delimits the boundary of each ubiquitin monomer, resulting in isoforms that splice stochastically to include a variable number of ubiquitin monomers [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Polyubiquitin Gene Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| MPRA (Massively Parallel Reporter Assay) | Systematically identifies functional splice sites within genes [12] | Tests every position in pre-mRNA; high-throughput; identifies cryptic sites |

| Southern Blot Analysis | Determines exact gene size and repeat number [11] | Resolves multiple bands from PCR; confirms repeat number without slippage artifacts |

| Isogenic Strain Series | Controls for genetic background in repeat number studies [11] | Engineered variants differing only in ubiquitin repeat number |

| DUBs (Deubiquitinating Enzymes) | Processes polyubiquitin precursors to mature ubiquitin [11] | Cleaves ubiquitin precursors; essential for ubiquitin monomer release |

| Heat Shock Elements (HSEs) Reporters | Studies stress-induced regulation of polyubiquitin genes [3] | Identifies promoter elements responsive to stress |

The structural organization of UBB and UBC polyubiquitin genes with their tandem ubiquitin repeats represents a fascinating evolutionary solution for maintaining cellular ubiquitin homeostasis, particularly under stress conditions. The conserved nature of UBB with its constant 3 repeats contrasts with the variable repeat number in UBC, suggesting complementary biological roles in maintaining the ubiquitin pool.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Understanding the molecular mechanisms that maintain repeat stability in UBB while allowing variation in UBC.

- Elucidating how repeat number variation influences UPS kinetics and substrate specificity in different cellular contexts.

- Exploring the therapeutic potential of modulating polyubiquitin gene expression or repeat number in protein aggregation diseases.

The unusual gene architecture of polyubiquitin genes, with their tandem repeats and specialized splicing mechanisms, continues to provide insights into the complex regulation of proteostasis and the evolutionary adaptations that maintain cellular function under diverse environmental challenges.

Ubiquitin (Ub) is a master regulator of cellular physiology, controlling the stability, activity, and localization of a vast array of proteins. While its role in stress responses is well-documented, the constitutive expression of ubiquitin—the maintenance of basal ubiquitin pools under normal physiological conditions—is equally critical for cellular homeostasis. This basal pool, composed of free ubiquitin readily available for conjugation and a dynamic equilibrium of ubiquitin-protein conjugates, serves as the fundamental resource for essential processes including cell cycle progression, signal transduction, and basal protein turnover [13] [14]. The cellular ubiquitin pool is remarkably abundant, constituting up to 5% of total cellular protein in some contexts, yet the free, unconjugated fraction is maintained at precise levels to ensure immediate availability without wasteful overproduction [13] [15]. Disruption of this delicate balance, through either depletion or chronic overproduction, has severe consequences, ranging from developmental defects and disrupted differentiation to increased susceptibility to proteotoxic stress [14]. This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms that maintain basal ubiquitin pools, the quantitative dynamics of these pools, and the experimental approaches for their study, framed within the broader context of polyubiquitin gene organization and regulation.

Quantitative Characterization of Cellular Ubiquitin Pools

Composition and Distribution of Ubiquitin Species

The cellular ubiquitin pool is not a single entity but a collection of distinct species in dynamic equilibrium. Understanding the quantitative distribution of these species is essential for appreciating ubiquitin homeostasis. The pool is primarily divided into free ubiquitin (monomeric and unanchored chains) and conjugated ubiquitin (covalently attached to substrate proteins) [13]. Under basal conditions, the free ubiquitin pool is surprisingly small relative to the conjugated fraction, indicating that ubiquitin is not produced in large excess but is rather efficiently recycled [15]. The conjugated fraction itself comprises a diverse array of modifications, including monoubiquitination, multiubiquitination, and polyubiquitin chains of various linkage types, each with distinct functional consequences [16].

Advanced proteomic techniques have enabled absolute quantification of these different ubiquitin species. For instance, the Ubiquitin Protein Standard Absolute Quantification (Ub-PSAQ) method involves affinity-capturing free ubiquitin species with Ub-binding Zn finger (BUZ) domains and polyubiquitin chains with Ub-associated (UBA) domains, followed by trypsin digestion and LC-ESI TOF MS analysis [13]. Similarly, the Absolute Quantification (AQUA) strategy utilizes stable isotope-labeled synthetic peptide standards to quantify specific polyubiquitin chain linkages in biological specimens via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [13]. These approaches reveal that the ubiquitin system maintains a precise balance of different linkage types under basal conditions, with perturbations to this balance having significant functional impacts.

Table 1: Quantitative Distribution of Ubiquitin Pools in Mammalian Cell Lines Under Basal Conditions

| Cell Line | Total Ubiquitin (μg Ub/mg protein) | Primary Contributing Genes | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa (HPV18+) | 4.74 ± 0.12 | UBC, UBA52 | Standard reference level |

| U2OS (Osteosarcoma) | 4.13 ± 0.005 | UBC, UBB | Comparable to HeLa |

| C33A (p53 mutated) | Lower than HeLa | UBB, UBA52 | Altered ubiquitin content |

| SiHa (HPV16+) | Lower than HeLa | UBB, UBA52 | Altered ubiquitin content |

| Caski (HPV16+) | Lower than HeLa | UBB, UBA52 | Altered ubiquitin content |

Consequences of Ubiquitin Homeostasis Disruption

The critical importance of maintaining basal ubiquitin levels becomes evident when examining the phenotypic consequences of its disruption. Genetic studies in mice have demonstrated that homozygous deletion of the polyubiquitin gene Ubc leads to mid-gestation embryonic lethality, primarily due to defects in fetal liver development [14] [3]. This is accompanied by delayed cell-cycle progression and increased susceptibility to cellular stress [3]. Similarly, Ubb knockout mice exhibit infertility and adult-onset neurodegeneration in the hypothalamus, accompanied by metabolic and sleep abnormalities [14] [15].

At the cellular level, a reduced free ubiquitin pool impairs fundamental processes. In neural stem cells (NSCs), ubiquitin deficiency delays the degradation of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), leading to aberrant Notch signaling activation, which in turn suppresses neurogenesis and promotes premature gliogenesis [14]. This disruption of differentiation processes highlights how basal ubiquitin levels directly influence cell fate decisions. Conversely, chronic ubiquitin overexpression also proves detrimental, leading to synaptic dysfunction in neurons through excessive degradation of proteins such as glutamate ionotropic receptors (GRIA1-4) [14]. These findings establish that ubiquitin levels must be maintained within a specific range for normal cellular function, with deviations in either direction causing pathological outcomes.

Ubiquitin Gene Organization and constitutive Expression

Genomic Architecture of Ubiquitin Genes

In mammals, the basal ubiquitin pool is maintained through the coordinated expression of four ubiquitin-encoding genes, which can be categorized into two classes based on their structure and regulation. The first class comprises the monomeric ubiquitin-ribosomal fusion genes, UBA52 and RPS27A (also known as UBA80). These genes encode a single ubiquitin moiety fused to the C-terminus of ribosomal proteins L40 and S27a, respectively [13] [14] [15]. They are generally considered to be constitutively expressed, providing a baseline supply of ubiquitin for fundamental cellular processes. The second class consists of the stress-inducible polyubiquitin genes, UBB and UBC. These genes contain tandem repeats of ubiquitin coding units without fusion partners—UBB typically has 3-4 repeats, while UBC contains 9-10 repeats [13] [14] [3]. Despite their classification as stress-inducible, both UBB and UBC make significant contributions to the basal ubiquitin pool under normal physiological conditions [15].

The UBC gene, located on chromosome 12q24.31 in humans, consists of two exons [3]. Its promoter region contains putative heat shock elements (HSEs) and binding sites for transcription factors including NF-κB, Sp1, HSF1, and AP-1, which mediate its inducibility under stress conditions [14]. Intriguingly, the intron region of UBC also plays a crucial regulatory role in basal expression. The presence of Yin Yang 1 (YY1)-binding sequences within the intron is essential for maintaining basal UBC expression levels, with mutation of these sequences significantly reducing transcriptional activity [14]. This complex regulatory architecture allows for fine-tuning of UBC expression across different cellular contexts and conditions.

Diagram 1: Mammalian ubiquitin gene organization and UBC regulation.

Regulatory Mechanisms Maintaining Basal Expression

The maintenance of basal ubiquitin levels involves sophisticated regulatory mechanisms that operate at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. While the polyubiquitin genes UBB and UBC are upregulated during stress, their expression is tightly controlled under normal conditions to prevent significant fluctuations in the ubiquitin pool [14]. This tight regulation is evidenced by the observation that ectopic ubiquitin overexpression leads to compensatory downregulation of endogenous polyubiquitin gene expression [14]. Intriguingly, when ubiquitin is overexpressed, UBC pre-mRNA levels increase while mature mRNA levels decrease, suggesting that ubiquitin homeostasis involves post-transcriptional regulation, potentially through effects on splicing or mRNA stability [14].

The basal expression of polyubiquitin genes displays cell-type specificity, reflecting the differential ubiquitin requirements of various tissues and cellular states [17] [15]. This specificity is mediated by distinct combinations of transcription factors and regulatory elements. For example, in muscle cells, the MAPK signaling pathway and Sp1 transcription factor binding are involved in regulating UBC basal expression [14] [3]. The existence of multiple UBC transcript variants arising from different transcription start sites further adds to the regulatory complexity, allowing for fine-tuned expression under various physiological conditions [15]. This sophisticated regulatory network ensures that basal ubiquitin production is precisely matched to cellular demands, maintaining homeostasis without unnecessary expenditure of energy and resources.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitin Pools

Methodologies for Quantifying Ubiquitin Pools and Dynamics

Accurately measuring the different species within the cellular ubiquitin pool is essential for understanding ubiquitin homeostasis. Traditional methods like immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies provide qualitative information but have limitations in precise quantification and distinguishing between free and conjugated ubiquitin [13]. To address these challenges, several advanced methodologies have been developed:

Ubiquitin ELISA (Ub-ELISA): This method involves converting all ubiquitin conjugates to monomeric free ubiquitin using the ubiquitin-specific protease Usp2-cc, followed by quantification via indirect competitive ELISA. This approach allows accurate determination of total ubiquitin levels but cannot distinguish between different ubiquitin species [13].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics: These approaches provide the most detailed analysis of ubiquitin pool dynamics. The Absolute Quantification (AQUA) strategy utilizes stable isotope-labeled synthetic peptide standards to quantify specific polyubiquitin chain linkages in biological specimens [13]. Trypsin digestion of ubiquitinated proteins yields a signature K-ε-GG peptide (due to a mass shift of 114 Da from the Gly-Gly modification on lysine), which can be detected and quantified via tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) [13] [18].

Ubiquitin Protein Standard Absolute Quantification (Ub-PSAQ): This comprehensive method involves affinity-capturing free ubiquitin species with Ub-binding Zn finger (BUZ) domains and polyubiquitin chains with Ub-associated (UBA) domains. Following elution and trypsin digestion, peptide fragments are analyzed via liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-ESI TOF MS) and quantified against stable isotope-labeled standards [13]. This approach enables accurate measurement of diverse cellular ubiquitin pools.

Tandem Fluorescent Timer (TFT) Reporters: For monitoring ubiquitin-dependent degradation dynamics in live cells, engineered constructs containing degrons appended to tandem fluorescent timers can be employed. TFTs are fusions of a rapidly maturing green fluorescent protein (GFP) and a slower maturing red fluorescent protein (RFP), whose output ratio provides a measure of protein turnover rates [19].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflows for ubiquitin pool quantification.

Manipulating Ubiquitin Gene Expression

To establish causal relationships between ubiquitin pool dynamics and cellular phenotypes, researchers need methods to experimentally manipulate ubiquitin levels. Traditional approaches include knockout and knockdown strategies to reduce ubiquitin availability. For instance, homozygous deletion of Ubc in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) results in decreased cellular ubiquitin levels and reduced viability under oxidative stress [14] [3]. More recently, advanced genetic tools have been developed to precisely upregulate ubiquitin genes:

The inducible dCas9-VP64 system enables reversible upregulation of endogenous polyubiquitin genes, even under normal conditions where such upregulation does not typically occur [17]. This system utilizes a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to the transcriptional activation domain VP64. When combined with single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeted to the regulatory regions of UBC (such as the promoter or intron), and further enhanced with MS2-p65-HSF1, this system can recruit transcriptional machinery to induce UBC expression [17]. The system is induced by doxycycline treatment, which triggers expression of the dCas9-VP64 fusion protein. A key advantage of this approach is its reversibility and the ability to modulate endogenous gene expression without ectopic overexpression, making it more physiologically relevant for studying the effects of increased ubiquitin availability on cellular processes [17].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Ubiquitin Homeostasis

| Reagent/Method | Primary Function | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AQUA Peptides | Absolute quantification of specific Ub chain linkages | Targeted analysis of chain-type dynamics; biomarker validation | Requires synthetic isotope-labeled peptides; specific instrumentation |

| Ub-PSAQ System | Comprehensive quantification of diverse Ub species | Global Ub pool analysis; homeostasis studies | Complex workflow; requires affinity domains and MS expertise |

| Inducible dCas9-VP64 | Reversible upregulation of endogenous Ub genes | Study gain-of-function effects; probe gene regulation | Enables temporal control; more physiological than ectopic expression |

| TFT-Degron Reporters | Live-cell monitoring of protein turnover | UPS activity measurements; drug screening | Requires reporter expression; confounded by non-UPS effects |

| Usp2-cc Protease | Conversion of Ub conjugates to free Ub | Total Ub quantification (ELISA); sample preprocessing | Loses information on chain types and conjugates |

Advancing research in ubiquitin homeostasis requires specialized reagents and tools designed to probe specific aspects of the ubiquitin system. The following table summarizes essential research solutions for investigating constitutive ubiquitin expression and pool dynamics:

Table 3: Advanced Research Tools for Ubiquitin Homeostasis Investigation

| Tool Category | Specific Reagents | Research Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Standards | Stable isotope-labeled AQUA peptides; Ub-PSAQ standards | Absolute quantification of Ub species; method calibration | Enables precise quantification; requires specialized MS resources |

| Genetic Modulators | Inducible dCas9-VP64 system; UBC/UBB sgRNAs; Cre-lox models | Endogenous gene regulation; tissue-specific knockout studies | Physiological relevance; reversible manipulation; complex implementation |

| Activity Reporters | TFT-degron constructs; N-end rule reporters; Ub-GFP fusions | Real-time UPS activity monitoring; substrate-specific degradation | Live-cell imaging compatible; may not reflect endogenous substrates |

| Affinity Reagents | BUZ domains (free Ub); UBA domains (chains); K-ε-GG antibodies | Enrichment of specific Ub species; proteomic sample preparation | Selective capture; workflow compatibility; potential binding preferences |

| Enzymatic Tools | Usp2-cc; other DUBs; E1/E2/E3 enzyme sets | In vitro ubiquitination assays; sample processing; enzyme characterization | Defined enzymatic activity; controlled reaction conditions |

Emerging Research Applications and Future Directions

The precise manipulation and measurement of basal ubiquitin pools open new avenues for therapeutic intervention and fundamental biological discovery. As research progresses, several emerging applications are coming into focus:

The integration of quantitative ubiquitin proteomics with genetic approaches enables systems-level understanding of how ubiquitin homeostasis impacts broader cellular networks. For instance, genetic variation in ubiquitin system genes can create substrate-specific effects on proteasomal degradation, as demonstrated by natural genetic variants that influence the N-end rule pathway in yeast [19]. Such variations can alter the abundance of numerous proteins without affecting their mRNA levels, representing an important source of post-translational regulation in gene expression [19].

In the therapeutic realm, understanding the regulation of polyubiquitin genes offers potential strategies for modulating ubiquitin availability in disease contexts. For example, in neurodegenerative diseases characterized by protein aggregation, targeted upregulation of polyubiquitin genes might enhance clearance of toxic species [13] [15]. Conversely, in cancers where ubiquitin-dependent degradation of tumor suppressors is accelerated, fine-tuning the ubiquitin pool might restore normal degradation dynamics [20] [21]. The ongoing development of USP7 inhibitors and other deubiquitinating enzyme modulators highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting components that influence ubiquitin recycling and availability [20].

Future research directions will likely focus on developing more precise tools for monitoring and manipulating ubiquitin pools in specific cellular compartments, understanding the interorgan and intertissue dynamics of ubiquitin homeostasis, and elucidating how basal ubiquitin levels are adjusted during developmental transitions and in response to metabolic cues. The continued refinement of CRISPR-based gene regulation systems, coupled with increasingly sophisticated proteomic methodologies, will empower researchers to address these complex questions and further illuminate the critical role of constitutive ubiquitin expression in cellular homeostasis.

Key Cis-Acting Elements and Trans-Acting Factors in Polyubiquitin Gene Promoters

Ubiquitin (Ub) is a highly conserved 76-amino-acid protein that serves as a crucial post-translational modification signal in eukaryotic cells, regulating diverse processes including proteasomal degradation, stress response, signal transduction, and membrane trafficking [14]. In metazoans, the cellular ubiquitin pool is maintained by four genes: two monoubiquitin genes (UBA52 and UBA80/RPS27A) that encode ubiquitin fused to ribosomal proteins, and two polyubiquitin genes (UBB and UBC) that encode multiple ubiquitin units arranged in head-to-tail tandem repeats [14] [22]. The polyubiquitin genes, particularly UBC, play a pivotal role in meeting cellular ubiquitin demands during embryonic development and in response to environmental stressors such as oxidative, heat-shock, and proteotoxic stress [14] [22]. This technical guide comprehensively details the key cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors that regulate polyubiquitin gene promoters, providing essential information for researchers investigating ubiquitin homeostasis and developing therapeutic strategies targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Polyubiquitin Gene Structure and Promoter Organization

The polyubiquitin genes UBB and UBC share a conserved organizational structure consisting of a promoter region, non-coding exon (exon 1/2), intron, and coding exon (exon 2/2) that encodes the ubiquitin repeats [14] [22]. The UBC gene typically contains 2-3 times more ubiquitin coding units compared to UBB [14]. The regulatory regions of these genes contain various cis-acting elements that bind trans-acting factors to precisely control gene expression under both basal and stress conditions [14].

Table 1: Fundamental Structure of Mammalian Polyubiquitin Genes

| Component | Genomic Features | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter Region | Contains TATA box, multiple transcription factor binding sites (NF-κB, Sp1, AP-1, HSF1) | Initiates transcription; responsive to stress and developmental signals |

| Non-coding Exon | Exon 1/2, 5'-untranslated region (5'-UTR) | Contains regulatory information; contributes to transcript stability |

| Intron | Located in 5'-UTR; contains enhancer elements including YY1 binding sites | Critical for basal expression regulation; mediates intron enhancement effect |

| Coding Exon | Exon 2/2; encodes ubiquitin monomer repeats in head-to-tail array | After translation and processing, provides multiple ubiquitin monomers |

The following diagram illustrates the organizational structure of a typical polyubiquitin gene and its key regulatory components:

Key Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements

Cis-acting elements are specific DNA sequences within the gene regulatory regions that serve as binding platforms for transcription factors and other regulatory proteins. Research has identified several critical cis-acting elements in polyubiquitin gene promoters that control their expression patterns.

Heat Shock Elements (HSEs)

The UBC promoter contains multiple heat shock elements (HSEs) that mediate stress-responsive upregulation. A comprehensive molecular dissection of the human UBC promoter identified three functional HSEs with distinct configurations and roles [23]:

- Distal HSE1 (nt -841/-817): Binds HSF1 and HSF2; activates transcription under proteotoxic stress

- Distal HSE2 (nt -715/-691): Binds HSF1 and HSF2; activates transcription under proteotoxic stress

- Proximal HSE (nt -100/-65): Binds HSF family members; functions as a negative regulator of stress-induced transcription

This discovery of HSEs with opposing functions on the same promoter represents a novel regulatory mechanism for fine-tuning ubiquitin expression according to cellular needs [23].

Intronic Regulatory Elements

The intron located within the 5'-untranslated region (5'-UTR) of polyubiquitin genes contains critical cis-regulatory elements that dramatically influence gene expression. In the human UBC gene, the 812-nucleotide intron contains binding sites for transcription factors including Yin Yang 1 (YY1) [24]. Mutation of YY1 binding sequences significantly reduces promoter activity and impairs intron removal from both endogenous and reporter transcripts, indicating a role in splicing regulation [24].

In plants, a novel cis-regulatory element termed the "U-box" (GCTGTAC) has been identified in the Nicotiana tabacum polyubiquitin gene Ubi.U4 promoter. This element directs formation of strong protein-DNA complexes and point mutations within this motif abolish complex formation and reduce promoter activity [25].

Table 2: Key Cis-Acting Elements in Polyubiquitin Gene Promoters

| Element Type | Genomic Location | Sequence Features | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Shock Elements (HSEs) | UBC promoter: -841/-817, -715/-691, -100/-65 | Multiple inverted repeats of nGAAn pentanucleotide | Stress-responsive regulation; two distal elements activate, proximal element represses transcription |

| YY1 Binding Sites | UBC intron (5'-UTR) | ATGGCGG sequence | Regulates basal expression; enhances splicing efficiency; mediates intron enhancement |

| Sp1 Binding Sites | UBC promoter and intron | GGGNGG sequence | Maintains basal expression; responds to MAPK signaling |

| U-box | N. tabacum Ubi.U4 promoter | GCTGTAC | Novel plant-specific element critical for promoter activity |

| TATA Box | Core promoter | TATA sequence | Basal transcription initiation |

| AP-1 Site | Promoter region | TGANTCA | Responds to stress and mitogenic signals |

| NF-κB Site | Promoter region | GGRRNYYYCC | Links ubiquitin expression to inflammatory signaling |

Trans-Acting Regulatory Factors

Trans-acting factors are proteins that recognize and bind specific DNA sequences to regulate gene expression. Multiple transcription factors have been identified that interact with polyubiquitin gene regulatory elements.

Heat Shock Factors (HSFs)

HSF1 and HSF2 bind to HSEs in the UBC promoter in response to proteotoxic stress induced by proteasome inhibitors such as MG132 [23]. Both HSF1 and HSF2 occupy the UBC promoter during heat stress, with HSF1 serving as the master regulator of the heat shock response [23]. The functional interplay between different HSF family members and their binding to HSEs with opposing functions provides a sophisticated mechanism for adjusting ubiquitin synthesis to cellular requirements.

Yin Yang 1 (YY1)

YY1 is a multifunctional transcription factor that binds to specific sequences within the intron of the UBC gene. YY1 binding is essential for maximal promoter activity, as demonstrated by the significant reduction in expression when YY1 binding sites are mutated or when YY1 is knocked down [24]. YY1 motifs enhance gene expression specifically when located within the intron in its native position, supporting a context-dependent mechanism rather than functioning as a typical enhancer [24].

Specificity Protein 1 (Sp1)

Sp1 binds to GC-rich sequences in the UBC promoter and intron regions. In muscle cells, Sp1 works in concert with the MAPK signaling pathway to regulate UBC basal expression, particularly in response to glucocorticoids like dexamethasone [14] [22]. Sp1 represents an important link between extracellular signals and ubiquitin homeostasis.

The following diagram illustrates the complex interplay between cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors in regulating polyubiquitin gene expression:

Experimental Analysis of Polyubiquitin Gene Regulation

Promoter Dissection Methodologies

Comprehensive understanding of polyubiquitin gene regulation has been achieved through systematic promoter analysis employing multiple experimental approaches.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

EMSA has been instrumental in identifying protein-DNA interactions in polyubiquitin gene promoters. The standard protocol involves [23]:

- Nuclear Extract Preparation: Cells are treated with stressors (e.g., 20μM MG132 for 4 hours) followed by low salt/detergent cell lysis and high salt extraction of nuclei

- DNA Probe Preparation: PCR amplification of promoter fragments (e.g., six overlapping fragments spanning nt -916/+4 of human UBC promoter)

- Binding Reactions: Incubation of nuclear extracts with labeled DNA probes in binding buffer

- Electrophoresis: Separation of protein-DNA complexes from free DNA on non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels

- Competition and Supershift Assays: Specificity confirmation using unlabeled competitors and antibodies against specific transcription factors

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays validate in vivo binding of transcription factors to polyubiquitin gene promoters [23]:

- Cross-linking: Formaldehyde treatment of cells to fix protein-DNA interactions

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Sonication to fragment DNA to 200-500 bp

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubation with specific antibodies (e.g., anti-HSF1, anti-HSF2)

- Reversal of Cross-links and DNA Purification

- PCR Analysis: Amplification of specific promoter regions using designed primers

Reporter Gene Assays

Functional validation of cis-regulatory elements employs luciferase reporter constructs [23] [24]:

- Construct Generation: Cloning of wild-type and mutated promoter sequences into pGL3-basic vector

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Introduction of specific mutations in transcription factor binding sites using kits such as QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit

- Cell Transfection: Introduction of constructs into relevant cell lines (e.g., HeLa cells)

- Treatment and Measurement: Stress induction (e.g., 20μM MG132 for 8 hours) followed by luciferase activity measurement

Key Experimental Findings

Application of these methodologies has yielded critical insights into polyubiquitin gene regulation:

- HSE Functionality: The two distal HSEs in the UBC promoter (-841/-817 and -715/-691) are responsible for upregulation in response to proteasome inhibition, while the proximal HSE (-100/-65) functions as a negative regulator [23]

- YY1 Mechanism: YY1 binding sequences in the UBC intron are required for maximal promoter activity, with YY1 silencing causing downregulation of luciferase mRNA levels. YY1 motifs enhance expression only when the intron is in its native position, supporting intron-mediated enhancement rather than typical enhancer function [24]

- Splicing Coupling: Mutagenesis of YY1 binding sites and YY1 knockdown negatively affect UBC intron removal, indicating that YY1 influences both transcription and splicing efficiency [24]

Table 3: Experimental Approaches for Analyzing Polyubiquitin Gene Regulation

| Method | Key Applications | Critical Reagents/Resources | Primary Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMSA | Identification of protein-DNA interactions; mapping transcription factor binding sites | Nuclear extracts from stressed cells; labeled promoter fragments; transcription factor antibodies | Validation of HSF binding to HSEs; identification of YY1 and Sp1 binding |

| ChIP | In vivo verification of transcription factor binding to native chromatin | Formaldehyde; specific antibodies against HSF1, HSF2, YY1; PCR primers for promoter regions | Confirmation of HSF1/HSF2 occupancy on UBC promoter during stress |

| Reporter Assays | Functional analysis of promoter activity; quantification of regulatory element contribution | pGL3-basic vector; site-directed mutagenesis kits; luciferase assay system | Determination of HSE activating/repressing functions; YY1-mediated enhancement |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Functional dissection of specific cis-elements | QuikChange Mutagenesis Kit; mutagenic primers for HSE, YY1, Sp1 sites | Demonstration of essential nature of YY1 sites and distal HSEs |

| RNA Interference | Investigation of trans-acting factor requirements | YY1-specific siRNAs; transfection reagents | Confirmation of YY1 role in basal UBC expression and splicing |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Studying Polyubiquitin Gene Regulation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | HeLa (cervical cancer), Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) | Model systems for stress response and developmental regulation | UBC promoter analysis; knockout studies [14] [23] |

| Stress Inducers | MG132 (20μM), Lactacystin (10μM), Heat Shock | Proteasome inhibition; proteotoxic stress induction | HSE activation studies; stress-responsive regulation [23] |

| Antibodies | Anti-HSF1, Anti-HSF2, Anti-YY1, Anti-Sp1 | Transcription factor detection; supershift EMSA; ChIP | Validation of factor binding to promoter elements [23] [24] |

| Cloning Vectors | pGL3-basic luciferase vector | Reporter gene constructs | Promoter activity quantification [23] [24] |

| Mutagenesis Kits | QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduction of specific mutations in cis-elements | Functional analysis of transcription factor binding sites [24] |

| siRNAs | YY1-specific siRNAs | Knockdown of trans-acting factors | Investigation of YY1 requirement in UBC expression [24] |

| Nuclear Extract Kits | Commercial nuclear extract preparation kits | Source of transcription factors for in vitro assays | EMSA experiments; transcription factor identification [23] |

Regulatory Mechanisms in Context

Basal Expression Maintenance

Under normal physiological conditions, polyubiquitin gene expression is tightly regulated to maintain ubiquitin homeostasis. The intron region plays a particularly important role in basal expression regulation, as removal of the intron region from UBC significantly decreases basal expression levels [14] [22]. The YY1 transcription factor binding to sequences within the intron is a key determinant of basal expression, with mutation of YY1 binding sites or YY1 knockdown resulting in dramatically reduced promoter activity [24].

The cooperative action of multiple transcription factors including Sp1, YY1, and AP-1 maintains basal expression across different cell types, with specific mechanisms varying depending on cellular context [14]. In muscle cells, for example, activation of the MAPK signaling pathway by glucocorticoids and Sp1 transcription factor binding are particularly important for UBC basal expression regulation [14] [22].

Stress-Responsive Upregulation

Under stress conditions such as proteotoxic, oxidative, or heat shock, polyubiquitin genes are significantly upregulated to provide additional ubiquitin for protein quality control. This response is primarily mediated through the HSEs in the promoter region that bind HSF1 and HSF2 [23]. The discovery that the UBC promoter contains both activating and repressing HSEs reveals a sophisticated regulatory system that allows precise adjustment of ubiquitin synthesis according to stress severity and duration [23].

This stress-responsive upregulation is essential for cell viability, as demonstrated by reduced cell survival when free ubiquitin levels fail to increase under stress conditions due to polyubiquitin gene disruption [14] [22].

Developmental and Tissue-Specific Regulation

Polyubiquitin genes show distinct expression patterns during embryonic development and across different tissues. Knockout studies in mice have revealed that Ubc knockout embryos are lethal by 12.5 days post coitum due to defects in fetal liver development, while Ubb knockout mice show spermatogenesis arrest leading to infertility [14] [22]. These phenotypes demonstrate the essential role of polyubiquitin genes in specific developmental processes and highlight that the two polyubiquitin genes have non-redundant functions despite encoding identical ubiquitin monomers.

When ubiquitin levels are perturbed through disruption of one polyubiquitin gene, compensatory expression of the other polyubiquitin gene may occur, but this compensation is often incomplete due to different expression patterns across cells and tissues [14] [22].

The regulation of polyubiquitin gene expression represents a sophisticated system for maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis under both normal and stress conditions. The complex interplay between cis-acting elements (including HSEs, YY1 binding sites, Sp1 sites, and the plant-specific U-box) and trans-acting factors (HSF1, HSF2, YY1, Sp1) allows cells to precisely adjust ubiquitin synthesis according to developmental needs and environmental challenges. The experimental methodologies detailed in this guide—including EMSA, ChIP, reporter assays, and site-directed mutagenesis—have been instrumental in deciphering this regulatory code. Continuing research in this field will further elucidate the nuanced mechanisms of polyubiquitin gene regulation and provide new opportunities for therapeutic interventions in diseases characterized by ubiquitin system dysfunction.

The Role of YY1 and Intronic Sequences in Regulating UBC Basal Expression

The Ubiquitin C (UBC) gene is one of four genes encoding the essential protein ubiquitin in mammals and plays a critical role in maintaining cellular ubiquitin homeostasis [14] [3]. Unlike monoubiquitin genes that encode ubiquitin fused to ribosomal proteins, UBC is a polyubiquitin gene containing multiple tandem repeats of ubiquitin coding units, typically nine to ten in humans [14] [3]. This gene organization allows for the production of substantial ubiquitin quantities, particularly under stressful conditions where ubiquitin demand increases significantly [14] [15]. The UBC gene is structurally characterized by a unique 5'-untranslated region (5'-UTR) containing a single 812-nucleotide intron located between the first non-coding exon and the coding sequence that contains the ubiquitin repeats [26] [27]. While UBC's responsiveness to various stressors has been well-documented, the mechanisms governing its basal expression under physiological conditions have emerged as a complex regulatory process involving specialized intronic sequences and specific transcription factors, most notably the Yin Yang 1 (YY1) protein [26] [24].

Within the broader context of polyubiquitin gene organization research, understanding UBC basal regulation provides crucial insights into how cells maintain ubiquitin equilibrium without producing excess ubiquitin under normal conditions [14] [28]. This precise control is essential for cellular viability, as demonstrated by embryonic lethality in UBC knockout mice and various pathological conditions associated with disrupted ubiquitin homeostasis in humans [14] [3]. This technical review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms through which YY1 and intronic sequences regulate UBC basal expression, providing detailed experimental protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers investigating ubiquitin gene regulation.

Molecular Anatomy of the UBC Gene Promoter and Regulatory Regions

The human UBC gene is located on chromosome 12q24.31 and spans approximately 5,764 base pairs [3]. The promoter region of UBC contains several conserved regulatory elements that contribute to its expression profile. Initial characterization revealed putative binding sites for multiple transcription factors, including Sp1, NF-κB, AP-1, and HSF1, as well as a canonical TATA box element [29] [27]. Deletion analyses have demonstrated that the core promoter elements necessary for maximal basal activity reside within the -371 to +878 nucleotide region relative to the transcription start site [26] [27]. This region encompasses the proximal promoter sequence, the first non-coding exon (63 nucleotides), and the unique 812-nucleotide intron of the 5'-UTR [26].

A critical discovery in understanding UBC regulation was the identification of the intron as an essential component for maximal promoter activity. Early experiments showed that removal of the 5'-UTR intron resulted in a drastic reduction (approximately 80-90%) of reporter gene expression, highlighting its indispensable role in UBC transcription [26] [29] [27]. Subsequent investigations revealed that this intronic enhancement effect could not be replicated by heterologous introns, indicating sequence-specific rather than general splicing-mediated mechanisms [29] [24]. Within this intronic region, specific cis-acting elements were identified, including binding motifs for the Sp1/Sp3 transcription factors and, most notably, multiple binding sites for the YY1 transcription factor [26] [29] [24].

Table 1: Key Regulatory Elements in the UBC 5'-UTR Intron

| Regulatory Element | Sequence/Characteristics | Identified Function | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| YY1 Binding Sites | ATGGCGG (multiple copies) | Essential for maximal promoter activity and splicing efficiency | EMSA, site-directed mutagenesis, knockdown experiments [26] |

| Sp1 Binding Sites | GGGNGG (multiple copies) | Contributes to enhancer activity | EMSA, supershift assays, ectopic expression [29] |

| Splice Sites | Consensus 5' and 3' splice sites | Required for intron removal and mRNA processing | Mutagenesis of splice sites [26] |

| Intronic Enhancer | +137/+766 region | Potent transcriptional enhancer activity | Deletion analysis, reporter assays [29] |

YY1: A Key Trans-acting Factor in UBC Regulation

Structural and Functional Characteristics of YY1

Yin Yang 1 (YY1) is a multifunctional transcription factor belonging to the GLI-Kruppel class of zinc finger proteins that can act as either an activator or repressor depending on cellular context and co-factors [30]. The protein contains a DNA-binding domain composed of four zinc fingers that recognize specific nucleotide sequences, including the core motif ATGGCGG found within the UBC intron [26] [24]. YY1 is known to regulate numerous cellular processes, including differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis, through its ability to modulate gene expression [30]. In the context of UBC regulation, YY1 functions primarily as a transcriptional activator, though its mechanism of action appears distinct from typical enhancer factors [26].

Experimental Evidence for YY1's Role in UBC Expression

Multiple lines of experimental evidence establish YY1 as a crucial regulator of UBC basal expression. Mutagenesis studies demonstrated that specific disruption of YY1 binding sites within the UBC intron resulted in a significant reduction (approximately 60-70%) of promoter activity in reporter assays [26] [24]. Similarly, RNA interference-mediated knockdown of YY1 expression caused corresponding decreases in both endogenous UBC mRNA levels and reporter gene expression driven by the UBC promoter [26]. Further mechanistic investigations revealed that YY1 binding sites failed to enhance gene expression when the intron was repositioned upstream of the proximal promoter, regardless of orientation [26] [24]. This positional constraint indicates that YY1 does not function as a typical enhancer element but rather operates through a context-dependent mechanism consistent with intron-mediated enhancement (IME) [26].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of YY1 Perturbation on UBC Expression

| Experimental Approach | System | Effect on UBC Expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| YY1 binding site mutagenesis | Reporter constructs in HeLa, SiHa, U2OS cells | ~60-70% reduction in promoter activity | [26] |

| YY1 knockdown | siRNA in HeLa cells | ~50% reduction in UBC mRNA | [26] |

| Intron repositioning | Reporter constructs with intron moved upstream | Loss of enhancer activity regardless of orientation | [26] [24] |

| Splice site mutagenesis | Unspliceable intron variants | Near-complete loss of promoter activity | [26] |

Intron-Mediated Enhancement: Mechanisms and Specificity

Intron-mediated enhancement describes the phenomenon where introns significantly boost gene expression through mechanisms that extend beyond simple enhancer functions or splicing effects [26] [29]. In the case of UBC regulation, several lines of evidence support the classification of its intronic enhancement as IME. First, the enhancing effect is position-dependent, requiring the intron to reside within its native context in the transcribed region rather than functioning as a typical enhancer that can operate from various positions and orientations [26] [24]. Second, the enhancement requires both specific cis-elements (YY1 binding sites) and an intact splicing apparatus, as demonstrated by the near-complete loss of promoter activity when splice sites are mutated [26].

The molecular mechanism linking YY1 binding to enhanced UBC expression involves facilitation of intron removal efficiency. Experimental evidence shows that mutagenesis of YY1 binding sites or YY1 protein knockdown negatively affects the splicing efficiency of the UBC intron in both endogenous genes and reporter constructs [26]. This represents a novel regulatory paradigm where a sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factor directly influences splicing efficiency of its host intron, creating a coordinated mechanism for tuning gene expression levels [26] [24]. This mechanism may explain how cells maintain precise control over ubiquitin production under basal conditions without the dramatic fluctuations characteristic of stress responses.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Reporter Construct Design and Analysis

The functional characterization of UBC regulatory elements has relied heavily on luciferase reporter assays in various cell lines. The standard approach involves cloning specific UBC promoter fragments into promoter-less vectors upstream of the firefly luciferase coding sequence [26] [29] [27]. Key constructs include:

- P3 construct: Contains nucleotides -371 to +876 (relative to transcription start site), including the proximal promoter, first exon, and intron [26] [24]

- P7 construct: Similar to P3 but lacks the 5'-UTR intron (+65 to +876) [26] [24]

- Modified constructs: Various derivatives with specific deletions, orientation changes, or site-directed mutations [26]

In a typical experiment, these constructs are transfected into relevant cell lines (e.g., HeLa, SiHa, U2OS), and luciferase activity is measured 24-48 hours post-transfection and normalized to co-transfected control vectors (e.g., Renilla luciferase) [26] [29]. This approach allows quantitative assessment of promoter activity and the functional impact of specific regulatory elements.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis of Transcription Factor Binding Sites

Critical insights into YY1 function came from systematic mutagenesis of its binding sites within the UBC intron [26] [24]. The experimental protocol typically involves:

- Identification of putative YY1 binding sites through bioinformatic analysis (consensus: ATGGCGG)

- Design of mutagenic primers that alter critical nucleotides required for YY1 binding (e.g., changing ATGGCGG to AGTGCAC)

- PCR-based mutagenesis using systems such as the QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit

- Verification of successful mutagenesis by DNA sequencing

- Functional assessment of mutated constructs using reporter assays [26]

Similar approaches have been applied to Sp1 binding sites (changing GGGNGG to ACANGG) and splice site consensus sequences [26] [29].

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSA)

EMSA provides direct evidence for transcription factor binding to specific intronic sequences [26] [29]. The standard protocol includes:

- Preparation of nuclear extracts from relevant cell lines

- Labeling of DNA probes corresponding to putative binding sites in the UBC intron

- Incubation of labeled probes with nuclear extracts

- Electrophoretic separation of protein-DNA complexes from free probe

- Specificity controls including competition with unlabeled wild-type or mutant oligonucleotides, and antibody-mediated supershift assays to confirm identity of binding proteins [26] [29]

For YY1 binding, supershift assays using anti-YY1 antibodies demonstrate direct interaction with specific intronic sequences [26].

Gene Silencing Approaches

Knockdown experiments using small interfering RNA (siRNA) or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting YY1 provide functional validation of its role in UBC regulation [26]. Typical protocols involve:

- Design and synthesis of sequence-specific YY1-targeting RNAi constructs

- Transfection into appropriate cell lines

- Confirmation of knockdown efficiency by measuring YY1 mRNA and/or protein levels

- Assessment of functional consequences on endogenous UBC expression (mRNA and protein) and reporter gene activity [26]

These approaches have consistently demonstrated that YY1 reduction leads to corresponding decreases in UBC expression and intron splicing efficiency [26].

Figure 1: Regulatory Network of YY1 and Intronic Sequences in UBC Expression Control. This diagram illustrates the mechanism by which YY1 binding to intronic motifs enhances UBC expression through improved splicing efficiency, and how elevated ubiquitin levels provide negative feedback to maintain homeostasis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating UBC Regulation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications and Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Constructs | P3 (-371/+878), P7 (-371/+64), intron-positioned variants | Quantification of promoter activity under different regulatory configurations | [26] [24] |

| Mutation Constructs | YY1 site mutants (ATGGCGG→AGTGCAC), Sp1 mutants, splice site mutants | Functional dissection of specific regulatory elements | [26] |

| Cell Lines | HeLa, SiHa, U2OS, NCTC-2544, HEK293 | Model systems for studying UBC regulation in different cellular contexts | [26] [28] [15] |

| YY1 Tools | YY1-specific siRNA/shRNA, anti-YY1 antibodies, expression vectors | Manipulation and detection of YY1 expression and binding | [26] [30] |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | UbK48R, UbK63R, UbG76A, UbΔGG, UbI44A | Dissection of ubiquitin-dependent feedback mechanisms | [28] |

| Analysis Methods | RT-qPCR primers for UBC variants, ubiquitin immunoassays | Quantification of gene expression and protein levels | [28] [15] |

Integration with Ubiquitin Gene Family Regulation

The regulation of UBC basal expression by YY1 and intronic sequences exists within the broader context of coordinated control across the ubiquitin gene family. Cells maintain ubiquitin homeostasis through sophisticated mechanisms that sense and respond to ubiquitin pool dynamics [14] [28]. Recent research has revealed that elevated ubiquitin levels trigger a negative feedback mechanism that specifically reduces UBC expression through effects on RNA splicing rather than transcription [28]. This feedback requires conjugation-competent ubiquitin, suggesting the involvement of ubiquitin-recognizing sensory mechanisms [28].

Notably, this ubiquitin-mediated downregulation specifically targets the polyubiquitin genes UBC and UBB, while expression of the monoubiquitin genes UBA52 and RPS27A remains relatively unchanged [28]. This differential regulation highlights the specialized roles of polyubiquitin genes as adjustable reservoirs for ubiquitin production, contrasting with the more constitutive expression of monoubiquitin genes [14] [28]. The discovery that YY1-mediated enhancement and ubiquitin-mediated repression converge on splicing efficiency suggests a sophisticated regulatory node for fine-tuning UBC expression in response to cellular needs.

Figure 2: Integrated Pathway of UBC Regulation and Ubiquitin Homeostasis. This workflow illustrates how stress signals activate YY1-mediated UBC expression through intron-mediated enhancement, while elevated ubiquitin pools provide negative feedback to maintain equilibrium.

The regulation of UBC basal expression represents a sophisticated mechanism for maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis through the integrated actions of YY1 transcription factor binding and intron-mediated enhancement. The dependency on specific intronic sequences and their positional constraints distinguishes this regulatory paradigm from conventional enhancer-mediated mechanisms and provides a precise system for tuning ubiquitin production to cellular requirements. The discovery that elevated ubiquitin levels feedback to modulate UBC splicing efficiency further reveals the dynamic equilibrium maintained through this system.

Future research in this area should focus on several key questions: (1) identifying the specific "ubiquitin sensor" mechanism that detects pool fluctuations and communicates this information to the splicing apparatus; (2) elucidating the structural basis for YY1's influence on spliceosome assembly or function; (3) exploring potential connections between UBC splicing efficiency and pathological conditions characterized by ubiquitin homeostasis disruption; and (4) developing targeted strategies to modulate UBC expression for therapeutic benefit in conditions where ubiquitin dysregulation contributes to disease pathogenesis. The continued investigation of YY1 and intronic sequences in UBC regulation will undoubtedly yield additional insights into the sophisticated mechanisms controlling ubiquitin gene expression and their implications for human health and disease.

From Bench to Bedside: Techniques for Manipulating Ubiquitin Pools and Therapeutic Applications

CRISPR-Based Strategies for Modulating Endogenous Polyubiquitin Gene Expression

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical regulatory mechanism that maintains cellular protein homeostasis through the selective degradation of proteins. Ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, is central to this process. In humans, the cellular ubiquitin pool is primarily supplied by two polyubiquitin genes, UBB and UBC, which encode ubiquitin head-to-tail tandem repeats [14]. UBB typically encodes three ubiquitin units, while UBC encodes nine [31]. These genes are tightly regulated under normal physiological conditions but undergo significant upregulation in response to various cellular stresses, including oxidative, proteotoxic, and heat shock stress [14].

Maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis is crucial for cellular viability. Disruption of this balance, through either insufficiency or excess, has severe pathological consequences. UBC knockout mice exhibit embryonic lethality by day 12.5 post coitum with defects in fetal liver development, while UBB knockout mice display infertility due to arrested spermatogenesis [14] [32]. Conversely, chronic ubiquitin overexpression in neurons leads to synaptic dysfunction by promoting excessive degradation of proteins like glutamate receptors [14]. These findings underscore the critical need for precise tools to modulate ubiquitin levels for both research and therapeutic purposes.