Ubiquitin Activation Across Kingdoms: From Evolutionary Origins to Therapeutic Targeting

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the ubiquitin activation cascade across diverse species, from prokaryotic antecedents to complex eukaryotes.

Ubiquitin Activation Across Kingdoms: From Evolutionary Origins to Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the ubiquitin activation cascade across diverse species, from prokaryotic antecedents to complex eukaryotes. We explore the foundational evolutionary biology of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes, detail cutting-edge methodological approaches for studying ubiquitination, address common experimental challenges, and present comparative analyses of system conservation and divergence. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights how understanding species-specific variations in ubiquitin activation reveals novel therapeutic targets and intervention strategies for cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and infectious diseases.

Evolutionary Origins and Core Mechanisms of Ubiquitin Activation

The ubiquitin (Ub)-signaling system, a hallmark of eukaryotic cells that regulates protein degradation, DNA repair, and signaling cascades, has its deepest evolutionary roots not in complex eukaryotes but in the simple, efficient sulfur incorporation pathways of prokaryotes [1]. Systematic analyses reveal that the core components of the eukaryotic Ub-conjugating system were already forming functional associations in bacteria, with key Ub-like proteins and their enzymatic partners predating the emergence of eukaryotes [1]. This evolutionary connection is primarily embodied by two prokaryotic sulfur carrier proteins: ThiS, involved in thiamine biosynthesis, and MoaD, essential for molybdenum cofactor (Moco) biosynthesis [1] [2]. These proteins, though functioning in metabolic pathways, share remarkable structural and mechanistic similarities with eukaryotic ubiquitin, suggesting a direct evolutionary pathway from bacterial sulfur metabolism to eukaryotic protein modification systems. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these prokaryotic antecedents, detailing the experimental evidence that links them to the ubiquitin system and framing these findings within the broader context of comparing ubiquitin activation across species.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitin-like Proteins and Sulfur Carriers

The structural and functional parallels between eukaryotic ubiquitin and the prokaryotic sulfur carriers ThiS and MoaD provide compelling evidence for an evolutionary relationship. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these proteins and their activation enzymes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitin-like Proteins and Prokaryotic Sulfur Carriers

| Feature | Eukaryotic Ubiquitin | Prokaryotic ThiS | Prokaryotic MoaD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Biological Role | Protein modification signaling [3] | Sulfur carrier in thiamine biosynthesis [1] | Sulfur carrier in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis [1] |

| Protein Fold | β-grasp fold [1] | β-grasp fold [1] | β-grasp fold [1] |

| C-terminal Motif | Conserved Gly-Gly [1] | Conserved terminal Glycine [1] | Conserved terminal Glycine [1] |

| Activation Enzyme | E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme [1] | ThiF (E1-like) [1] | MoeB (E1-like) [1] |

| Activation Mechanism | Adenylation → E1 thioester [1] | Adenylation → ThiF persulfide [1] | Adenylation [1] |

| Final Functional State | Ubiquitin-protein isopeptide bond [1] | ThiS-thiocarboxylate [1] | MoaD-thiocarboxylate [1] |

| Downstream Process | Proteasomal degradation, signaling [3] | Thiamine synthesis [1] | Molybdopterin synthesis [1] |

A critical insight from comparative analyses is that despite their different biological endpoints—protein modification in eukaryotes versus cofactor biosynthesis in prokaryotes—the core mechanistic architecture remains conserved. The E1-like enzymes ThiF and MoeB, similar to eukaryotic E1 enzymes, feature an amino-terminal Rossmann-fold nucleotide-binding domain and a carboxyl-terminal β-strand-rich domain containing conserved cysteines [1]. This structural conservation supports the hypothesis that the eukaryotic Ub-signaling apparatus was pieced together from pre-existing bacterial components involved in sulfur transfer.

Key Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Structural Characterization of the MoeB-MoaD Complex

Experimental Objective: To determine the crystal structure of the native MoeB-MoaD complex from Escherichia coli to elucidate the molecular mechanism of MoaD activation and its relationship to the ubiquitin activation pathway [2].

Methodology:

- Protein Expression and Purification: The MoeB and MoaD proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 system and subsequently purified [2].

- Crystallization and Data Collection: The complex was crystallized, and X-ray diffraction data were collected to a resolution of 1.70 Å [2].

- Structure Determination: The crystal structure was determined using X-ray diffraction and refined to an R-factor of 0.176 [2]. Multiple structures were analyzed: the apo complex, the ATP-bound form, and the MoaD-adenylate form [2].

Key Findings: The structural analysis revealed that MoeB activates the C-terminus of MoaD to form an acyl-adenylate, mirroring the initial step of ubiquitin activation by E1 enzymes [2]. Despite the lack of significant sequence similarity, MoaD and ubiquitin were found to share the same structural fold, including the conserved C-terminal Gly-Gly motif essential for activation [2]. These findings provided the first structural evidence suggesting that ubiquitin and E1 enzymes are derived from ancestral genes closely related to moaD and moeB [2].

Genomic Analysis of Prokaryotic Ubiquitin-Related Systems

Experimental Objective: To conduct a systematic analysis of prokaryotic Ub-related β-grasp fold proteins to identify novel family members and their functional associations [1].

Methodology:

- Sequence Profile Searches: Sensitive sequence profile searches were performed across prokaryotic genomes to identify Ub-related proteins beyond characterized ThiS, MoaD, TGS, and YukD domains [1].

- Analysis of Conserved Gene Neighborhoods: Genomic contexts were examined to identify conserved gene neighborhoods and domain architectures [1].

- Structural Analysis: Structural comparison using DALI program Z-scores and morphological examination of structures was conducted [1].

Key Findings: This bioinformatic approach revealed several conserved gene neighborhoods in phylogenetically diverse bacteria that combined genes for JAB domains (deubiquitinating isopeptidases), E1-like adenylating enzymes, and different Ub-related proteins [1]. Furthermore, sequence analysis identified Ub-conjugating enzyme/E2-ligase related proteins in these neighborhoods [1]. Most strikingly, genes for a Ub-like protein and a JAB domain peptidase were discovered in the tail assembly gene cluster of certain caudate bacteriophages [1]. These observations suggest that Ub family members had already formed strong functional associations with E1-like proteins, UBC/E2-related proteins, and JAB peptidases in bacteria, potentially functioning together in signaling systems analogous to those in eukaryotes [1].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications in Studying Ubiquitin Antecedents

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| MoeB-MoaD Complex | Structural studies of ubiquitin-like activation | X-ray crystallography [2] |

| E. coli BL21 Expression System | Recombinant protein expression | Production of MoeB, MoaD, and encapsulin proteins [2] [4] |

| Cysteine Desulfurase | Sulfur mobilization enzyme | Encapsulin cargo in sulfur metabolism [4] |

| ThiF Enzyme | E1-like adenylating enzyme for ThiS | Studies of thiamine biosynthesis pathway [1] |

| JAB Domain Proteases | Deubiquitinating isopeptidases | Analysis of prokaryotic ubiquitin-like signaling [1] |

| SrpI Encapsulin | Novel prokaryotic nanocompartment | Investigation of sulfur starvation response [4] |

Pathway Integration and Evolutionary Trajectory

The evolutionary relationship between prokaryotic sulfur carriers and the eukaryotic ubiquitin system can be visualized through the following pathway diagram, which highlights the conserved mechanisms and divergent biological functions:

Diagram 1: Evolutionary pathway from prokaryotic sulfur carriers to eukaryotic ubiquitin system

This diagram illustrates how the core molecular mechanism—activation of a β-grasp fold protein by a conserved enzyme—was conserved during evolution, while the biological application diverged significantly from sulfur metabolism for cofactor biosynthesis to targeted protein modification for regulatory purposes.

Implications for Ubiquitin Activation Research Across Species

The comparative analysis of ThiS, MoaD, and ubiquitin reveals fundamental insights with broad implications for understanding ubiquitin activation across species:

Conserved Core Mechanism: The adenylation of the C-terminal glycine by a conserved enzyme represents the central conserved mechanism from prokaryotes to eukaryotes [1] [2]. This suggests that the eukaryotic ubiquitin system evolved by repurposing an ancient biochemical mechanism for a new regulatory function.

Expanded Functional Repertoire: While prokaryotic sulfur carriers like ThiS and MoaD primarily function in specific metabolic pathways, genomic evidence suggests some prokaryotic Ub-like proteins may have already formed proto-signaling systems with E1-like enzymes, E2-related proteins, and JAB peptidases [1], representing an intermediate evolutionary stage.

Structural Conservation Precedes Sequence Conservation: The strong structural similarities between MoaD and ubiquitin despite minimal sequence homology [2] highlight that protein fold and mechanistic architecture are more conserved than primary sequence across evolutionary timescales.

Experimental Paradigms: The study of prokaryotic antecedents provides simplified model systems for understanding fundamental aspects of ubiquitin activation. For instance, the MoeB-MoaD complex offers a minimal two-component system for studying the structural basis of ubiquitin-like protein activation [2].

This evolutionary perspective enriches our understanding of the ubiquitin system's origins and provides researchers with conceptual frameworks and practical model systems for investigating the intricate mechanisms of ubiquitin activation across the spectrum of biological complexity.

Ubiquitin is a small, 76-amino acid protein that serves as a universal post-translational modifier in eukaryotic cells. Its discovery revealed a molecule of extraordinary evolutionary stability—a protein that has maintained virtually identical sequence and structure across eukaryotic organisms ranging from protozoa to humans [5]. This extreme conservation is unparalleled, with human and yeast ubiquitin sharing 96% sequence identity despite over a billion years of evolutionary divergence [6]. The ubiquitin fold represents one of nature's most successful and enduring structural designs, a β-grasp motif that has been repurposed for myriad cellular functions while maintaining its core architectural integrity.

The remarkable preservation of ubiquitin contrasts sharply with the expansive evolution of its regulatory machinery. While ubiquitin itself has remained virtually unchanged, the ubiquitin system has expanded into a sophisticated signaling network comprising hundreds of enzymes and binding partners [5]. This dichotomy highlights the unique evolutionary constraints on the ubiquitin molecule itself—its structure represents an optimal solution for interacting with diverse partners while maintaining stability under varying cellular conditions.

Evolutionary History: From Archaeal Ancestors to Eukaryotic Complexity

Prokaryotic Origins of Ubiquitin-like Signaling

The evolutionary roots of ubiquitin extend beyond eukaryotes into the archaeal and bacterial domains. Evidence reveals that simplified ubiquitin signaling systems exist in certain archaeal species, with Caldiarchaeum subterraneum possessing a minimal, operon-like ubiquitin system containing single copies of ubiquitin, E1, E2, E3, and deubiquitinase genes [5]. This arrangement represents the most simplified genetic architecture encoding a functional ubiquitin signaling pathway known to date.

Structural studies have revealed profound evolutionary connections despite minimal sequence similarity. The sulfur carrier protein ThiS from Escherichia coli, involved in thiamine biosynthesis, shares only 14% sequence identity with ubiquitin yet possesses an nearly identical ubiquitin fold [7]. This structural homology, combined with functional similarities in sulfur chemistry, demonstrates that eukaryotic ubiquitin and prokaryotic ThiS evolved from a common ancestor [7]. Similarly, Small Archaeal Modifier Proteins (SAMPs) in Haloferax volcanii represent ubiquitin-like protein modifiers that function in archaea without requiring the full E2-E3 enzymatic cascade of eukaryotic systems [5].

Expansion and Diversification in Eukaryotes

The transition to eukaryotic cells marked a dramatic expansion of the ubiquitin system. The Last Eukaryotic Common Ancestor (LECA) possessed a surprisingly complex ubiquitin signaling apparatus with essentially all major ubiquitin-related genes, including the SUMO and Ufm1 ubiquitin-like systems [8]. This expansion occurred through massive gene innovation and diversification of protein domain architectures during eukaryogenesis [8].

Unlike the operon organization found in archaea, eukaryotic ubiquitin genes are redundantly encoded in multiple loci, typically as head-to-tail concateners of multiple ubiquitin open reading frames or fusions with ribosomal proteins L40 and S27a [5] [6]. This genetic arrangement facilitates strong concerted evolution that maintains identical ubiquitin copies despite genomic redundancy [5].

Table: Evolutionary Distribution of Ubiquitin System Components

| Organismal Group | Ubiquitin Gene Organization | Key Enzymatic Components | System Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archaea | Single-copy gene in operon-like clusters | Minimal E1, E2, E3 components | Basic conjugation system |

| Protists | Multiple loci, including polyubiquitin genes | 100+ ubiquitin system genes in Naegleria gruberi | Diverse E2s and E3s |

| Fungi | Polyubiquitin genes and ribosomal fusions | Full E1-E2-E3 cascade | Complete system with specialized functions |

| Plants & Animals | Multiple ubiquitin genes and fusions | Expanded E2 and E3 families | Highly complex with regulatory networks |

Structural Analysis: The Molecular Basis of Extreme Conservation

The Ubiquitin Superfold Architecture

Ubiquitin adopts a compact β-grasp fold that exhibits exceptional stability across extreme conditions. The structure consists of a five-stranded β-sheet (β1-β5) cradling a central α-helix (α1), with a short 3₁₀ helix (η1) completing the architecture [9]. This configuration creates a stable protein core that resists denaturation at temperatures up to 95°C, unfolds only under mechanical forces exceeding 200 pN, and maintains integrity across broad pH ranges [9].

The structural stability derives from several key features:

- Hydrophobic core: A tightly packed interior minimizes solvent-accessible surface area

- Salt bridges: Strategic electrostatic interactions, including K11-E34 and H68-Y59, enhance stability

- Hydrogen bonding network: Extensive main-chain and side-chain H-bonds stabilize secondary structures

- Conserved residues: Critical hydrophobic positions (L8, I44, V70) and polar residues (T9, T14, T22) are maintained [9]

Table: Structural Features Contributing to Ubiquitin Stability

| Structural Element | Key Components | Functional Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| β-sheet (5 strands) | β1 (1-7), β2 (11-17), β3 (40-45), β4 (48-50), β5 (67-71) | Main structural scaffold, resistant to proteolysis |

| α-helix | α1 (23-34) | Stabilized by hydrophobic interactions with β-sheet |

| 3₁₀ helix | η1 (56-59) | Completes compact fold |

| Hydrophobic patch | L8, I44, V70 | Critical for binding interactions |

| Salt bridges | K11-E34, H68-Y59 | Enhanced thermostability |

| C-terminal tail | R74-G76 | Essential for conjugation |

Functional Surfaces and Binding Epitopes

Despite its small size, ubiquitin contains multiple functionally specialized surfaces that mediate specific interactions with diverse binding partners. The I44 hydrophobic patch (L8, I44, H68, V70) serves as the primary recognition site for many ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) [9]. Additional interaction surfaces include the TEK-box region around T14 and E34 for proteasome binding, and the N-terminal patch centered on R42 and T66 for specific UBD interactions [9].

Structural analyses of ubiquitin complexes reveal that the same fold can recognize diverse partners through surface plasticity and conformational adaptability. Ubiquitin can sample multiple conformational states in solution, allowing it to adapt to different binding partners while maintaining its core structure [9]. This versatility explains how a single conserved protein can participate in countless specific interactions within the cell.

Comparative Functional Analysis Across Species

Conservation of Functional Capabilities

The extreme sequence conservation of ubiquitin directly correlates with conserved functional capabilities across eukaryotic species. Ubiquitin from diverse organisms can functionally complement ubiquitin-deficient systems, demonstrating that the core biochemical functions have been maintained throughout evolution [5]. This functional conservation extends to:

- Proteasomal targeting: K48-linked polyubiquitin chains target substrates for degradation across eukaryotes

- DNA repair: K63-linked chains function in DNA damage response from yeast to humans

- Endocytic trafficking: Monoubiquitination serves as an endocytosis signal in diverse species

- Inflammatory signaling: Ubiquitin regulates NF-κB pathways through various chain types

Recent research has revealed that ubiquitin's functional repertoire extends beyond protein modification. Ubiquitin can modify non-protein substrates including lipids and sugars, and recent evidence demonstrates direct ubiquitination of small molecules such as the synthetic compound BRD1732 [10]. This expands the potential regulatory scope of ubiquitination beyond the proteome.

Species-Specific Adaptations

Despite overwhelming conservation, subtle species-specific differences exist in ubiquitination pathways. Computational analyses reveal differences in ubiquitination site sequence patterns between species, necessitating species-specific prediction models for accurate ubiquitination site mapping [11]. These differences primarily involve the enzymes that recognize ubiquitin (readers), write ubiquitin codes (writers), or remove ubiquitin (erasers), rather than ubiquitin itself.

The expansion of ubiquitin system components shows lineage-specific patterns, with multicellular lineages exhibiting the most complex ubiquitin systems in terms of protein domain architectures [8]. For example, plants and animals have independently expanded their ubiquitin signaling systems at the origins of multicellularity, developing additional regulatory layers while maintaining the core ubiquitin structure [8].

Experimental Analysis of Ubiquitin Structure and Function

Key Methodologies for Ubiquitin Research

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent/Method | Specific Example | Application in Ubiquitin Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 screening | Genome-wide knockout | Identification of essential ubiquitin system components [10] |

| Isopeptide linkage detection | Trypsin digestion with GlyGly-remnant mapping | Identification of ubiquitination sites [6] |

| Thioester formation assays | E2∼Ub formation with/without inhibitors | Analysis of ubiquitin conjugation kinetics [12] |

| Structural determination | NMR, X-ray crystallography | High-resolution structure analysis of ubiquitin complexes [7] [13] |

| Proteomic profiling | Ubiquitin remnant immunoaffinity profiling | System-wide identification of ubiquitination sites [11] |

| Species-specific prediction models | SSUbi algorithm | Accurate prediction of ubiquitination sites across species [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Ubiquitin Assays

Protocol 1: E2∼Ub Thioester Formation Assay

This assay measures the transfer of ubiquitin from E1 to E2 enzymes, a critical step in the ubiquitination cascade [12].

- Reaction Setup: Combine 100nM E1 enzyme, 1μM E2 enzyme, 10μM ubiquitin, and 2mM ATP in reaction buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl₂, 0.1mM DTT)

- Incubation: Conduct reactions at 30°C for precisely 3 minutes to minimize secondary ubiquitin linkages

- Termination and Analysis: Stop reactions with SDS-PAGE loading buffer lacking reducing agents, analyze by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies

- Inhibition Studies: Include potential inhibitors (e.g., MUB proteins at physiological concentrations) to assess their effect on E2 activation [12]

Protocol 2: Ubiquitination Site Mapping by Mass Spectrometry

This methodology identifies specific ubiquitination sites in substrate proteins [10] [6].

- Sample Preparation: Purify ubiquitinated proteins from cells under denaturing conditions to preserve modifications

- Proteolytic Digestion: Digest with trypsin under nondenaturing conditions, which cleaves ubiquitin after R74 to yield ubiquitin(1-74) while leaving the Gly76-Lys isopeptide bond intact

- GlyGly-Remnant Detection: Identify di-glycine modifications on lysine residues by mass spectrometry (detecting a +114.1 Da mass shift)

- Validation: Confirm sites by mutagenesis of modified lysines to arginine and functional assays

Visualization of Ubiquitin Signaling Pathways

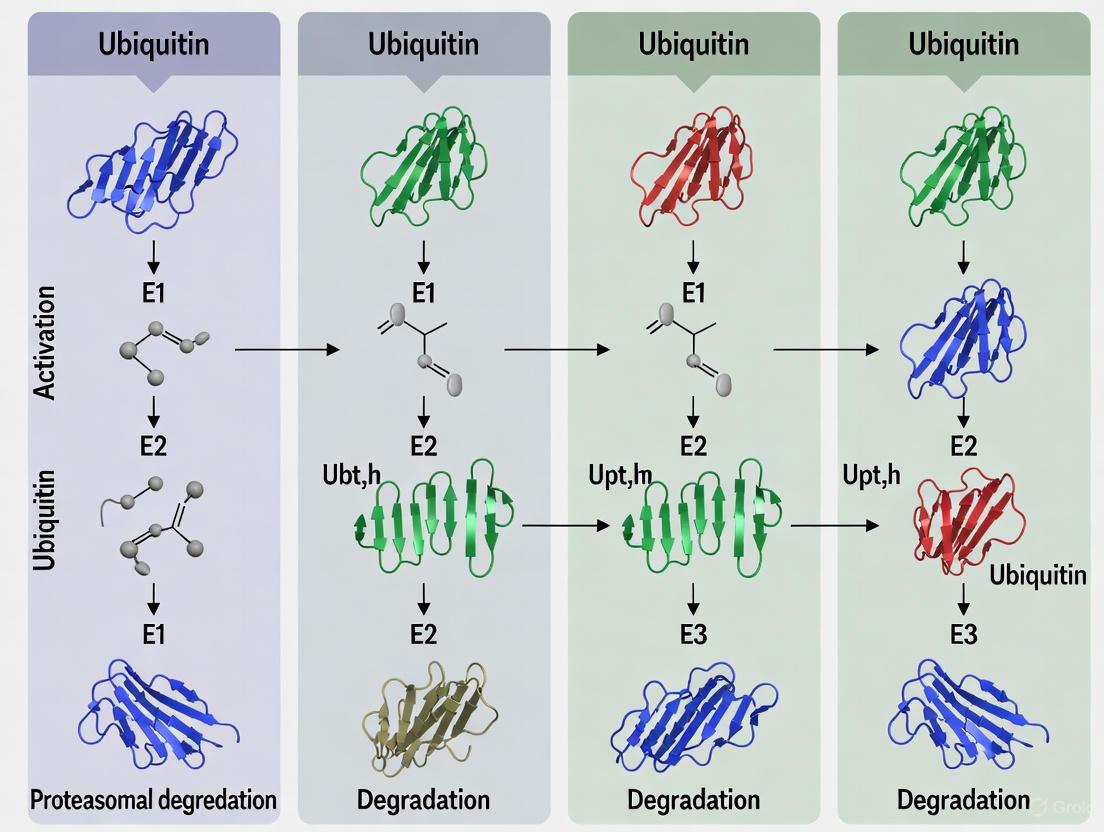

Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

Implications for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

The extreme conservation of ubiquitin makes it an attractive target for therapeutic intervention, as mechanisms discovered in model organisms frequently translate to human biology. Recent research has identified specific E2 enzymes, such as UBE2N, as dependencies in certain cancers including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [14]. UBE2N primarily synthesizes K63-linked ubiquitin chains that stabilize oncoproteins rather than targeting them for degradation, representing a novel therapeutic avenue [14].

The discovery of small molecules that interface with the ubiquitin system, such as BRD1732 that undergoes direct ubiquitination, reveals new mechanistic possibilities for therapeutic intervention [10]. Understanding the structural basis of ubiquitin's conservation provides a framework for developing compounds that target specific aspects of ubiquitin signaling while minimizing off-target effects.

Emerging technologies in ubiquitin research, including species-specific prediction models that integrate both sequence and structural information [11], are enhancing our ability to interpret ubiquitin signaling across different organisms. These advances leverage the conserved nature of ubiquitin while accounting for species-specific adaptations in the broader ubiquitin system.

Ubiquitin represents a paradigm of extreme molecular conservation—a protein that has maintained virtually identical sequence and structure throughout eukaryotic evolution while expanding its functional repertoire. The β-grasp fold exemplifies structural perfection for a signaling molecule: stable yet adaptable, compact yet functionally versatile. Its evolutionary journey from simple archaeal systems to complex eukaryotic networks demonstrates how nature can optimize a successful design while allowing regulatory complexity to expand around it.

The conservation of ubiquitin across species provides tremendous power for biomedical research, enabling discoveries in model organisms to directly inform human therapeutic development. As we continue to unravel the complexities of ubiquitin signaling, the fundamental stability of the ubiquitin fold itself ensures that these insights will apply across biological systems, from the simplest protists to humans.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a hallmark of eukaryotic cell regulation, controlling virtually all aspects of protein fate, from degradation to localization and activity [5]. At the apex of this system stand the E1 activating enzymes, which initiate the ubiquitination cascade by activating ubiquitin and transferring it to E2 conjugating enzymes [15]. While long considered a eukaryotic-specific innovation, groundbreaking research has revealed that the architectural and mechanistic blueprints of E1 enzymes originated in bacterial biosynthesis pathways [5] [15].

This article provides a comparative analysis of E1 enzyme architecture, tracing the evolutionary path from minimal bacterial ancestors ThiF and MoeB to the multi-domain eukaryotic E1s. We examine structural conservation, functional diversification, and experimental approaches that have elucidated these relationships, providing a comprehensive guide for researchers investigating ubiquitin activation across species.

Structural and Functional Comparison of E1-like Enzymes

Core Architectural Features

The E1 enzyme family shares a conserved catalytic core for ubiquitin-like protein (UBL) activation, with evolution building additional domains onto this foundation to regulate complexity and specificity.

Table 1: Comparative Features of E1-like Enzymes Across Species

| Feature | Bacterial ThiF/MoeB | Eukaryotic E1 (e.g., UBA1) |

|---|---|---|

| Organization | Homodimer [16] | Single polypeptide or heterodimer [16] |

| Molecular Mass | ~27 kDa (monomer) [16] | ~110 kDa [16] |

| Domains | Single adenylation domain [15] | Adenylation domain, Catalytic Cysteine Half-Domains (FCCH/SCCH), Ub-fold Domain (UFD) [17] |

| UBL Cargo | ThiS, MoaD [18] [15] | Ubiquitin, NEDD8, SUMO, etc. [15] |

| Primary Function | Sulfur carrier activation for thiamin/molybdopterin biosynthesis [18] [15] | Protein tag activation for post-translational modification [5] [15] |

| Key Catalytic Residues | ATP-binding Arg finger (from opposite monomer) [15] | Active-site Cysteine for thioester formation [15] [17] |

Evolutionary Trajectory and Functional Diversification

The evolutionary journey from bacterial precursors to eukaryotic E1s is marked by two key developments: domain fusion and functional specialization.

- Bacterial Origins: In E. coli, ThiF and MoeB function as homodimers, each monomer featuring an adenylation domain that recognizes UBL-fold proteins ThiS and MoaD, respectively [15] [16]. They catalyze adenylation of their cargo's C-terminus but do not form a thioester intermediate, instead facilitating sulfur transfer for biosynthesis of essential metabolites like thiamin [18] [15].

- Eukaryotic Expansion: Eukaryotic E1s incorporate the core adenylation domain but have fused additional domains, creating a multi-domain architecture. A critical evolutionary addition is the active-site cysteine domain, which allows the formation of a E1~UBL thioester bond intermediate—a key mechanistic step absent in the bacterial systems [15] [17]. The Ub-fold Domain (UFD) is another eukaryotic innovation that enhances specificity by recruiting cognate E2 enzymes [17].

This progression is exemplified by the catalytic cysteine (e.g., Cys600 in human UBA1), which is absent in ThiF/MoeB and enables the transthioesterification reaction central to the eukaryotic ubiquitination cascade [15] [17].

Diagram 1: Evolution of ubiquitin activation systems from simple bacterial precursors to complex eukaryotic cascades. The system gains complexity through the addition of dedicated E2 and E3 components, and the E1 enzyme evolves from a simple adenylator to a multi-domain orchestrator.

Experimental Approaches for Structural and Functional Analysis

Research in this field relies on structural biology techniques to visualize complexes and detailed biochemical assays to dissect the multi-step activation mechanism.

Structural Biology Workflows

Protein Complex Crystallization (as exemplified by E. coli ThiS-ThiF) [18]

- Cloning & Expression: The thiFS genes are cloned into a plasmid (e.g., pCLK1405) and transformed into an E. coli overexpression strain (e.g., BL834(DE3)).

- Protein Purification: Cells are lysed, and the supernatant is subjected to ammonium sulfate precipitation (50%). Further purification employs Hi-Trap QFF anion-exchange chromatography followed by size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex200).

- Crystallization: The purified ThiS-ThiF complex is concentrated to ~8 mg/mL and crystallized using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method against a reservoir containing 7-8% PEG 400, 35 mM CaCl₂, and 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0-7.3).

- Data Collection & Processing: X-ray diffraction data is collected at synchrotron sources (e.g., APS). The crystals typically belong to space group P2₁2₁2₁. Data is integrated and scaled using software like HKL2000, enabling structure determination and refinement.

Functional Biochemical Assays

E1 Activity and Inhibition Profiling [19]

- Multi-turnover Ubiquitination Assay: Reactions contain E1 (UBA1), E2 (UBE2L3 or UBE2D3), E3 (e.g., HUWE1HECT), Ub, ATP, and Mg²⁺, often with a fluorescent Ub variant. Reaction products are visualized by SDS-PAGE to monitor E3 autoubiquitination, E2~Ub thioester formation, and polyUb chain synthesis.

- Single-turnover Assays: To dissect specific catalytic steps, a pre-formed E1~Ub thioester is incubated with E2 in the absence of ATP. This isolates the transthioesterification step from the initial adenylation.

- Inhibitor Mechanism Studies: Compounds are tested in dose-response curves (IC₅₀ determination). To probe if an inhibitor is a substrate, reaction mixtures can be analyzed by LC-MS/MS after protease digestion (e.g., with LysC) to identify Ub-inhibitor conjugates (+ mass of inhibitor).

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Utility | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| HUWE1HECT | Isolated catalytic HECT domain of the HUWE1 E3 ligase. | Studying HECT E3-specific mechanics and inhibitor screening [19]. |

| UBE2L3 (E2) | E2 conjugating enzyme with specificity for HECT-type E3s. | In vitro ubiquitination assays to monitor Ub transfer from E1 to E3 [19]. |

| Vinylthioether HUWE1HECT~Ub Proxy | Stable, hydrolysis-resistant mimic of the E3~Ub thioester intermediate. | Probing the structure and dynamics of the key E3~Ub intermediate [19]. |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) | Measures protein thermal stability changes upon ligand binding. | Detecting potential interactions between an E1/E3 and small molecules [19]. |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange MS (HDX-MS) | Probes protein conformational dynamics and ligand interactions. | Mapping binding interfaces and conformational changes in E1/E3 enzymes [19]. |

The comparative analysis of E1 enzyme architecture reveals a remarkable evolutionary story: the complex eukaryotic ubiquitin signaling machinery has its roots in fundamental bacterial metabolic pathways. The conserved adenylation domain serves as the universal structural and functional core, while the acquisition of additional domains in eukaryotes enabled the evolution of a sophisticated regulatory network.

Future research will continue to leverage high-resolution structural data and mechanistic biochemistry to fully elucidate the dynamic conformational changes that drive the E1 catalytic cycle [17]. Furthermore, the discovery of minimal, operon-encoded ubiquitination systems in archaea provides a powerful model for understanding the core principles of the UPS [5]. This evolutionary perspective is not merely academic; it informs drug discovery efforts, as evidenced by the ongoing development of E1 inhibitors as potential anticancer therapies [17]. Understanding the detailed architecture of these enzymes, from bacteria to humans, provides the fundamental knowledge required to manipulate this critical cellular machinery for therapeutic benefit.

{ARTICLE CONTENT}

Expansion of the Ubiquitin System: From Archaeal Operons to Eukaryotic Pyramidal Networks

The ubiquitin system represents a quintessential regulatory pathway that underwent profound expansion from a simple archaeal operon-like structure to a complex pyramidal network in eukaryotes. This comparative analysis examines the fundamental architectural differences, functional conservation, and evolutionary trajectory of ubiquitin activation across species. By integrating recent phylogenomic discoveries of Asgard archaea with mechanistic studies on ubiquitin-like protein (Ubl) conjugation, we delineate how a minimal, functionally versatile prokaryotic system transformed into the elaborate eukaryotic ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). Experimental data from gene shuffle complementation studies and structural analyses reveal remarkable functional conservation of core conjugation mechanisms despite extensive network diversification. This systematic comparison provides foundational insights for researchers investigating ubiquitin pathway evolution and targeting ubiquitin-related processes in drug development.

Ubiquitin is a small, highly conserved regulatory protein that serves as a central signaling molecule in eukaryotic cells, modulating critical processes including protein degradation, cell cycle control, DNA repair, and immune response [5] [6]. For decades, the ubiquitin system was considered a eukaryotic innovation; however, recent genomic and functional studies have identified ubiquitin-like signaling systems in archaea and bacteria, rewriting our understanding of its evolutionary origins [5] [20]. The discovery of simple, operon-encoded ubiquitin systems in archaea provides a crucial missing link for understanding how the elaborate eukaryotic ubiquitin machinery evolved from prokaryotic precursors.

The core ubiquitination process involves an enzymatic cascade where ubiquitin is activated by E1 enzymes, transferred to E2 conjugating enzymes, and finally attached to substrate proteins via E3 ligases [6]. This review performs a systematic comparison between the architectural organization, functional mechanisms, and evolutionary relationships of the minimal ubiquitin systems found in archaea and the complex pyramidal networks characteristic of eukaryotes. Understanding these systems' comparative biology has significant implications for fundamental cell biology research and drug discovery, particularly in developing therapies that target the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [21].

Architectural Evolution: From Operons to Pyramidal Networks

Archaeal Operons: Minimal Functional Units

The most streamlined genetic arrangement encoding a ubiquitin signaling system has been identified in archaea such as Caldiarchaeum subterraneum, consisting of just five genes organized in an operon-like cluster [5]. This minimal system includes: (1) a single-copy ubiquitin-like gene, (2) one ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), (3) one ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), (4) one RING-type ubiquitin-protein ligase (E3), and (5) one deubiquitinating enzyme related to the proteasome subunit Rpn11 [5]. This operon topology represents the most simplified ancestral pre-eukaryotic ubiquitin system known to date and demonstrates that the core components of the eukaryotic ubiquitin cascade were already present in prokaryotic organisms.

Similar operonic organizations are found sporadically distributed across diverse bacterial phyla (Actinobacteria, Planctomycetes, and Acidobacteria) and archaea, though they are frequently absent in close relatives, suggesting possible horizontal transfer events [5]. The protein modifiers in these systems, such as SAMPs (Small Archaeal Modifier Proteins) in Haloferax volcanii, function without requiring E2 and E3 conjugating factors in some cases, with the E1 enzyme alone being sufficient for conjugation—a mechanism distinct from the canonical eukaryotic three-enzyme cascade [5].

Eukaryotic Pyramidal Networks: Expanded and Diversified

In stark contrast to the minimalist archaeal systems, eukaryotic ubiquitin signaling is characterized by a vastly expanded pyramidal network with extensive gene duplication and functional specialization [5]. Rather than operon organization, eukaryotic ubiquitin genes are redundantly encoded in multiple loci: as polymeric head-to-tail concatemers of multiple ubiquitin open reading frames (approximately 4 to 15) and as fusions with ribosomal proteins L40 and S27a [5]. The enzymatic cascade follows a pyramidal hierarchy with a limited number of E1 enzymes (2 in humans) activating ubiquitin, which is then transferred to a larger set of E2 enzymes (over 30 in humans), and finally delivered to substrates by hundreds of E3 ligases that provide substrate specificity [5] [6].

This expansion creates a sophisticated regulatory network capable of precise spatiotemporal control over protein modification. For example, the amoebo-flagellate Naegleria gruberi, which diverged from other eukaryotic lineages over 1,000 million years ago, already contains more than 100 ubiquitin signaling system genes, including multiple E2s and E3s, demonstrating the early establishment of this pyramidal architecture in eukaryotic evolution [5].

Table 1: Comparative Architecture of Ubiquitin Systems in Archaea and Eukaryotes

| Feature | Archaeal Systems | Eukaryotic Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Organization | Operon-like clusters | Dispersed genes; tandem repeats |

| Ubiquitin/UBL Genes | Single copy | Multiple loci (polyubiquitin, fusions) |

| E1 Enzymes | One E1-like | Two E1s (UBA1, UBA6) in humans |

| E2 Enzymes | One E2 | 35 E2s in humans |

| E3 Ligases | One RING-type E3 | Hundreds of E3s |

| Deubiquitinases | One Rpn11-related | ~100 DUBs in humans |

| System Complexity | Minimal, compact | Pyramidal, hierarchical |

Evolutionary Bridging: Urm1 and the Sulfur Transfer Connection

Urm1: At the Crossroads of Evolution

The ubiquitin-related modifier 1 (Urm1) represents a crucial evolutionary link between prokaryotic sulfur carriers and eukaryotic ubiquitin-like modifiers [22] [20]. Urm1 is a unique Ubl protein with dual functionality, operating in both tRNA thiolation and protein urmylation, thereby combining features typical of bacterial sulfur carriers (like ThiS and MoaD) and classical ubiquitin-like modifiers [22] [23]. Phylogenetic analyses reveal that Urm1 proteins from archaea and eukaryotes form a monophyletic clade with solid bootstrap support (BS = 80), suggesting they share a common ancestor and likely represent an ancient Ubl family that predates the eukaryote-archaea divergence [22].

Structural and sequence comparisons show striking similarities between Urm1 from S. cerevisiae (ScUrm1) and S. acidocaldarius (SaciUrm1), particularly in the conserved β-grasp fold and C-terminal di-glycine motif characteristic of Ubl proteins [22]. This structural conservation across domains of life underscores the ancient origin of the β-grasp fold, which has been recruited for diverse biochemical functions including catalytic roles, scaffolding of iron-sulfur clusters, RNA binding, and sulfur transfer [20].

Experimental Evidence from Gene Shuffle Studies

Recent functional studies using URM1 gene shuffle from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius to Saccharomyces cerevisiae have provided direct experimental evidence for the functional conservation of urmylation across archaea and eukaryotes [22] [23]. When expressed in yeast urm1Δ deletion strains, the archaeal SaciUrm1 protein robustly conjugated to the peroxiredoxin Ahp1, a bona fide urmylation target in yeast, despite the evolutionary distance between these organisms [22].

Critical findings from this experimental approach include:

- Conserved Conjugation Specificity: Archaeal SaciUrm1 attached to the same lysine residue (Lys-32) on Ahp1 as yeast Urm1, following identical molecular requirements including dependence on specific cysteine residues (Cys-31, Cys-62) [22].

- Shared Activation Mechanism: Ahp1 conjugation required sulfur transfer onto the archaeal Urm1 modifier from Uba4, the E1-like urmylation activator in yeast, demonstrating conservation of the thioactivation mechanism [22].

- Functional Separation: While archaeal Urm1 supported protein urmylation, it could not rescue tRNA thiolation defects in yeast, indicating that the dual functions of Urm1 can be evolutionarily separated and that archaeal Urm1 may specialize in protein modification [22].

Table 2: Functional Comparison of Urm1 in Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and Saccharomyces cerevisiae

| Functional Aspect | SaciUrm1 (Archaea) | ScUrm1 (Yeast) |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Urmylation | Yes (to Ahp1) | Yes (to Ahp1 and other targets) |

| tRNA Thiolation | No | Yes |

| Thioactivation Required | Yes (by Uba4) | Yes (by Uba4) |

| E1 Activator | Uba4 (yeast) | Uba4 |

| Major Acceptor Site on Ahp1 | Lys-32 | Lys-32 |

| Critical Cysteine Residues | Cys-31, Cys-62 | Cys-31, Cys-62 |

These findings position Urm1 at the evolutionary crossroads of prokaryotic sulfur transfer and eukaryotic protein conjugation pathways, providing a living molecular fossil that bridges these functionally distinct systems [22].

Methodologies for Comparative Ubiquitin System Analysis

Phylogenomic and Genomic Approaches

Advanced phylogenomic analyses leveraging expanded genomic datasets have revolutionized our understanding of ubiquitin system evolution. Recent studies have identified 16 new Asgard archaeal lineages at the genus level or higher, substantially expanding the known phylogenetic diversity of archaea most closely related to eukaryotes [24]. Sophisticated phylogenomic approaches using complex site-heterogeneous evolution models in maximum likelihood and Bayesian inferences with recoded alignments have helped resolve the contentious placement of eukaryotes within the Asgard archaeal lineage [24].

Standardized marker sets have been developed for robust phylogenetic analysis, including:

- GTDB.ar53: 53 archaeal-specific marker proteins from the Genome Taxonomy Database [24]

- S67 Marker Set: 67 markers (39 ribosomal proteins, 28 functional proteins) conserved across all sampled archaeal genomes [24]

- NM200 and NM57: Non-ribosomal protein markers of archaeal origin [24]

These tools enable researchers to reconstruct evolutionary relationships with greater accuracy and assess the functional conservation of ubiquitin system components across domains of life.

Functional Complementation Assays

Gene shuffle complementation experiments, such as those conducted with URM1 from S. acidocaldarius to S. cerevisiae, provide direct functional assessment of conservation [22]. The experimental workflow typically involves:

- Strain Construction: Creating deletion mutants (e.g., urm1Δ) in model eukaryotic organisms

- Heterologous Expression: Introducing archaeal genes under appropriate promoters

- Phenotypic Rescue Assessment: Testing complementation of mutant phenotypes

- Biochemical Validation: Confirming protein conjugation through electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and Western blotting with isopeptidase inhibitors

- Mechanistic Analysis: Identifying critical residues through site-directed mutagenesis

These functional assays are complemented by molecular dynamics simulations that reveal how subtle changes in amino acid sequences—such as single aspartic to glutamic acid substitutions—can dramatically alter interaction selectivity between E2 and E3 enzymes by shifting the equilibrium between "open" (binding-competent) and "closed" (binding-incompetent) states [25].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitin System Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Archaeal Strains | Comparative functional studies | Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, Haloferax volcanii [22] [5] |

| Model Eukaryotes | Genetic manipulation and complementation | Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) [22] |

| Gene Knockout Strains | Functional assessment of specific genes | urm1Δ, uba4Δ, tum1Δ yeast strains [22] |

| Epitope Tags | Protein detection and purification | HA-tag, c-Myc tag [22] |

| Isopeptidase Inhibitors | Stabilization of ubiquitin/Ubl conjugates | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) [22] |

| Protocol Repositories | Standardized methods for working with archaea | ARCHAEA.bio, Halohandbook [26] |

| Strain Collections | Source of diverse archaeal strains | DSMZ, JCM, ATCC [26] |

| Phylogenomic Markers | Evolutionary analysis | GTDB.ar53, S67 marker sets [24] |

The comparative analysis of ubiquitin system organization from archaeal operons to eukaryotic pyramidal networks reveals fundamental principles of molecular evolution. The conservation of core mechanisms—from Urm1-mediated urmylation to the β-grasp fold structure—highlights the deep evolutionary origins of protein modification systems. Simultaneously, the dramatic expansion in eukaryotic systems demonstrates how gene duplication and functional specialization enabled the development of sophisticated regulatory networks essential for eukaryotic complexity.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these evolutionary insights offer valuable perspectives. The minimal archaeal systems provide simplified models for understanding core ubiquitination mechanisms, while the functional conservation of enzymes like Uba4 across domains suggests ancient, essential processes that might be targeted therapeutically. Furthermore, the evolutionary trajectory of the ubiquitin system illustrates how essential cellular machinery expands and diversifies, offering parallels for understanding other complex biological systems in eukaryotic cells.

Visual Guide: Ubiquitin System Architecture and Experimental Analysis

Ubiquitin System Evolution and Architecture

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin System Architectural Evolution. This schematic illustrates the evolutionary transition from minimal archaeal operons to complex eukaryotic pyramidal networks, with Urm1 representing a key functional bridge between these organizational paradigms.

Experimental Workflow for Cross-Domain Functional Analysis

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Cross-Domain Functional Analysis. This flowchart outlines the key methodological approach for assessing functional conservation of ubiquitin system components between archaea and eukaryotes, incorporating genetic, biochemical, and computational techniques.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that controls a vast array of cellular processes, including protein degradation, DNA repair, and immune signaling. This enzymatic cascade begins with E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes, which activate and transfer ubiquitin to downstream E2 and E3 enzymes [27]. For years, UBA1 (UBE1) was considered the sole E1 enzyme for ubiquitin activation in eukaryotes. However, the discovery of UBA6 (E1-L2) revealed unexpected complexity in the initiation of ubiquitin signaling [28]. These two E1 enzymes, while performing the same fundamental biochemical reaction, exhibit distinct structural characteristics, E2 specificities, and evolutionary conservation patterns [29] [28].

Understanding the phylogenetic distribution of UBA1 and UBA6 provides valuable insights into the evolution of protein degradation systems and cellular regulatory mechanisms across species. This comparative guide examines the experimental evidence defining the presence, conservation, and functional specialization of these E1 enzymes throughout the animal kingdom, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for investigating ubiquitin activation pathways in different model organisms and therapeutic contexts.

Comparative Analysis of UBA1 and UBA6

Phylogenetic Distribution Across Species

Table 1: Phylogenetic Distribution of E1 Enzymes Across Species

| Species Group | UBA1 Presence | UBA6 Presence | Key Evidence & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mammals (Human, Mouse) | Yes | Yes | UBA6 activates both ubiquitin and FAT10; essential for embryonic development in mice [30] [28] |

| Birds | Presumed | Presumed | Likely present given vertebrate conservation |

| Reptiles/Amphibians | Presumed | Presumed | Likely present given vertebrate conservation |

| Sea Urchin | Yes | Yes | Experimental confirmation of UBA6 presence [28] |

| Ascidians (Halocynthia roretzi) | Yes | Yes | cDNA cloning confirms presence of both E1s; involvement in fertilization [31] |

| Insects (D. melanogaster) | Yes | No | UBA6 absent from genome [29] |

| Nematodes (C. elegans) | Yes | No | UBA6 absent from genome [29] |

| Fungi (Yeast) | Yes | No | UBA6 absent from genome [29] |

| Plants | Yes | No | UBA6 absent from genome [29] |

The phylogenetic distribution of UBA1 and UBA6 reveals a striking evolutionary pattern. UBA1 demonstrates universal conservation across eukaryotic organisms, serving as the foundational ubiquitin activation system [29]. In contrast, UBA6 exhibits a restricted phylogenetic presence, appearing only in vertebrates, sea urchin, and ascidians, while being conspicuously absent from insects, nematodes, fungi, and plants [29] [28]. This distribution suggests UBA6 emerged later in evolutionary history to fulfill specialized regulatory functions not required in all eukaryotic lineages.

The conservation of UBA6 in deuterostomes but not in protostomes or simpler eukaryotes indicates this E1 enzyme may have evolved to support increasingly complex cellular regulatory mechanisms in higher organisms. In ascidians such as Halocynthia roretzi, both UBA1 and UBA6 play crucial roles in fertilization, with the 3D protein structures predicted to be very similar to their human counterparts based on AlphaFold2 predictions [31]. The absence of UBA6 from model organisms like Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans highlights the importance of considering phylogenetic distribution when selecting model systems for studying ubiquitin pathways.

Structural and Functional Characteristics

Table 2: Structural and Functional Comparison of UBA1 and UBA6

| Characteristic | UBA1 | UBA6 |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Activation | Yes | Yes |

| FAT10 Activation | No | Yes [30] |

| Primary E2 Partners | Charges most E2s (UBE2A, UBE2B, CDC34) | Charges USE1 (UBA6-specific E2) [29] |

| Cellular Localization | Nuclear and cytoplasmic isoforms [27] | Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial association [31] |

| Catalytic Mechanism | Open/closed conformational transition during adenylation/thioester formation | Similar conformational transition; allosterically regulated by InsP6 [30] |

| Inhibitor Sensitivity | Sensitive to TAK-243 [27] | Less sensitive to TAK-243; potentially inhibited by phytic acid [27] |

| Disease Associations | VEXAS syndrome (M41 mutations) [27]; Aortic dissection [32] | Potential therapeutic target in VEXAS syndrome [27] |

Structurally, UBA1 and UBA6 share a similar domain organization including adenylation domains, catalytic cysteine half-domains, and ubiquitin-fold domains, yet they possess distinct features that underlie their functional specialization. UBA1 exists in two naturally occurring isoforms: UBA1a (nuclear) initiated from methionine 1, and UBA1b (cytoplasmic) initiated from methionine 41 [27]. In VEXAS syndrome, mutations at M41 cause an aberrant isoform switch to a nonfunctional UBA1c, demonstrating the critical importance of this regulatory mechanism [27].

UBA6 exhibits dual substrate specificity, uniquely capable of activating both ubiquitin and the ubiquitin-like modifier FAT10 [30] [33]. Structural studies reveal UBA6 undergoes dramatic conformational changes during catalysis, transitioning between "open" and "closed" states during adenylation and thioester bond formation [30]. Surprisingly, UBA6 is allosterically regulated by inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6), which binds to a conserved basic pocket in the SCCH domain and inhibits enzyme activity by altering conformational equilibria [30]. This represents a previously unknown regulatory mechanism for E1 enzymes.

Functionally, UBA1 and UBA6 operate in parallel pathways with distinct E2 partnerships. UBA1 charges the majority of E2 enzymes, including UBE2A/B and CDC34 family members, while UBA6 specifically charges the USE1 (UBA6-specific E2) enzyme [29] [28]. Despite this separation, both pathways can converge on the same E3 ligases, such as the UBR1-3 family of N-recognins, to mediate substrate ubiquitination in a spatially distinct manner [29].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Phylogenetic Analysis and Gene Identification

Experimental identification of E1 enzymes across species employs complementary bioinformatic and molecular techniques:

Database Mining: Researchers search genomic databases (ANISEED for ascidians) using known E1 sequences to identify candidate gene models [31]. This approach identified seven potential UBA candidates in Halocynthia roretzi before UBA1 and UBA6 were confirmed.

cDNA Cloning: Using degenerate primers or RACE PCR, researchers isolate full-length coding sequences from target species. For ascidian UBA1 and UBA6, this involved cloning from gonad-derived cDNA libraries [31].

Sequence Analysis: Predicted protein sequences are analyzed for characteristic E1 domains (AAD, IAD, FCCH, SCCH, UFD) and key catalytic residues (e.g., Cys625 in human UBA6) [30]. 3D structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 enable comparative structural analysis between orthologs [31].

Functional Validation: Recombinant enzymes are tested for ubiquitin adenylation, thioester bond formation, and E2 charging capabilities to confirm functional conservation [33].

Functional Characterization Assays

Several established biochemical approaches define E1 enzyme activity and specificity:

ATP-PPᵢ Exchange Assays: Measure the first step of ubiquitin activation where E1 catalyzes ubiquitin adenylation with release of inorganic pyrophosphate. This assay demonstrated UBA6's ability to activate both ubiquitin and FAT10 [33].

Thioester Formation Assays: Detect the formation of covalent E1~ubiquitin intermediates under non-reducing conditions. Immunoblotting of UBA1 in VEXAS models confirmed the aberrant UBA1b-to-UBA1c isoform switch [27].

E2 Charging Assays: Evaluate the transfer of ubiquitin from E1 to candidate E2 enzymes. These assays revealed UBA6's exclusive E2 partnership with USE1, while UBA1 charges multiple E2s [29] [28].

Inhibitor Studies: Compound sensitivity profiles help distinguish E1 activities. TAK-243 preferentially inhibits UBA1, while phytic acid shows selectivity for UBA6 in cellular models [27].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for phylogenetic and functional analysis of E1 enzymes

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for E1 Enzyme Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Inhibitors | TAK-243 (MLN7243) [27] | Selective UBA1 inhibition; studying UBA1-specific functions | First-in-class specific E1 inhibitor; in clinical trials for cancer |

| PYR-41 [31] | General E1 inhibition; fertilization studies | Less specific; inhibits multiple E1 enzymes and deubiquitinases | |

| Phytic acid [27] | Potential UBA6 inhibition; exploring UBA6-specific vulnerabilities | Natural compound; allosterically inhibits UBA6 via InsP6 binding [30] | |

| Cell Models | UBA1M41V THP1 [27] | VEXAS syndrome modeling | Human monocytic cell line with engineered UBA1 M41V mutation |

| BAPN-induced AD mouse [32] | Aortic dissection studies | In vivo model showing UBA1 upregulation in vascular disease | |

| CFBE41o- F508del [34] | Cystic fibrosis research | Airway epithelial cells with F508del-CFTR for ubiquitin-proteasome studies | |

| Antibodies | Anti-UBA1 [34] | Protein expression analysis | Western blot, immunohistochemistry |

| Anti-UBA6 [34] | Protein expression and localization | Western blot, immunocytochemistry | |

| Anti-ubiquitin [27] | Ubiquitination status assessment | Detection of global ubiquitination changes | |

| Biochemical Assays | ATP-PPi Exchange [33] | E1 activation step measurement | Quantifies initial ubiquitin/FAT10 adenylation |

| Thioester Assay [27] | Covalent intermediate detection | Non-reducing Western to detect E1~ubiquitin conjugates | |

| E2 Charging Assay [28] | E1-E2 specificity profiling | Identifies E2 partnerships for UBA1 vs UBA6 |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The phylogenetic restriction of UBA6 to deuterostomes suggests its emergence corresponded with increasing complexity in biological regulatory systems requiring specialized ubiquitination pathways. The differential E2 charging between UBA1 and UBA6 enables cells to maintain parallel ubiquitination cascades that may be activated under distinct physiological conditions or in response to specific cellular stresses [29] [28].

From a therapeutic perspective, the distinct structural features of UBA6, particularly its allosteric InsP6 binding site, offer opportunities for developing specific small-molecule inhibitors that could selectively target UBA6-dependent pathways without disrupting essential UBA1-mediated ubiquitination [27] [30]. The enhanced sensitivity of UBA1-mutant cells in VEXAS syndrome to UBA6 inhibition reveals a promising synthetic lethal relationship that could be exploited therapeutically [27].

Future research should focus on elucidating the complete repertoire of UBA6-specific substrates and pathways, particularly in physiological contexts where its dual specificity for ubiquitin and FAT10 provides unique regulatory potential. The development of more specific pharmacological tools, including conditional genetic models and highly selective inhibitors, will be essential for deciphering the non-redundant functions of these evolutionarily distinct E1 activation systems across different species and tissue types.

Figure 2: UBA6-specific ubiquitination cascade with allosteric regulation

Advanced Techniques and Pharmacological Modulation of Ubiquitin Activation

In Vitro and In Vivo Assays for E1 Enzyme Activity and Thioesterification

Ubiquitin-activating enzymes, known as E1 enzymes, stand at the apex of the ubiquitination cascade, a crucial post-translational modification system in eukaryotic cells. These ATP-dependent enzymes initiate a three-step enzymatic cascade by activating ubiquitin and transferring it to E2 conjugating enzymes, ultimately leading to substrate modification by E3 ligases [35] [36]. The clinical significance of E1 enzymes continues to grow, with research linking their dysfunction to various cancers, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoinflammatory diseases such as VEXAS syndrome, characterized by somatic mutations at methionine 41 in UBA1 [27] [37]. This comparison guide examines the current methodologies for assessing E1 enzyme activity and thioester formation, providing researchers with essential tools for investigating this fundamental biological process and developing targeted therapies.

Comparative Analysis of E1 Activity Assays

The following table summarizes the primary assays used to monitor E1 enzyme activity and thioester bond formation:

Table 1: Comparison of E1 Enzyme Activity and Thioesterification Assays

| Assay Type | Detection Method | Key Readout | Throughput | Biological Context | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UbiReal (Fluorescence Polarization) | Fluorescence Polarization (FP) | Real-time E1-E2-E3 activity & thioester formation | High | In vitro | Real-time kinetics, universal for Ub/UBLs, suitable for inhibitor screening [36] | Requires fluorescently-labeled ubiquitin |

| Thioester Assay | Western Blot/ Chemiluminescence | E1~Ub and E2~Ub thioester intermediates | Medium | In vitro | Direct detection of covalent thioester linkages [35] | Non-quantitative, endpoint measurement only |

| Radioactive Ub Charging | Radiolabel detection (³²P or ³⁵S) | ATP consumption or ³⁵S-labeled ubiquitin transfer | Low | In vitro | Highly sensitive | Radioactive hazard, specialized facilities required |

| Cell-Based Ubiquitination Monitoring | Immunoblotting | Accumulation of ubiquitin conjugates | Low | In vivo (cellular) | Physiological relevance, can detect endogenous ubiquitination [10] | Indirect measure of E1 activity |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Screening | Next-generation sequencing | Genetic dependencies & resistance mechanisms | Ultra-high | In vivo (cellular) | Unbiased discovery of E1 genetic networks [10] [27] | Indirect, requires validation |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

UbiReal Fluorescence Polarization Assay

The UbiReal platform represents a significant advancement for monitoring the complete ubiquitination cascade in real-time, including the critical E1-catalyzed thioester formation step [36].

Protocol Steps:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 20 μL reaction containing 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl₂, 0.1-1 μM E1 enzyme, 100-500 nM fluorescein-labeled ubiquitin (F-Ub), and optional E2/E3 enzymes.

- Instrument Configuration: Use a fluorescence polarization-compatible plate reader with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 528 nm.

- Kinetic Measurement: Monitor polarization values (mP units) immediately after adding E1 enzyme, taking readings every 30-60 seconds for 60-120 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Calculate reaction rates from the initial linear portion of the polarization increase curve. For inhibitor studies, pre-incubate E1 with compound for 15 minutes before adding other reaction components.

Technical Notes: The assay capitalizes on the significant change in molecular rotation when ubiquitin transitions from free diffusion (low polarization) to being covalently bound within the E1~Ub thioester complex (high polarization). For E1-E2 transthiolation monitoring, include appropriate E2 enzymes such as UBE2D3 or UBE2L3 [36].

In Vitro Thioester Assay

This traditional biochemical assay provides direct evidence of E1~Ub and E2~Ub thioester intermediate formation through electrophoretic mobility shift analysis under non-reducing conditions [35].

Protocol Steps:

- Thioester Formation: Incubate 50-100 nM E1 enzyme with 1-5 μM ubiquitin in reaction buffer (20-50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5-8.0, 5 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM ATP) for 5-15 minutes at 30°C.

- E2 Charging: For E2~Ub detection, add 1-5 μM of relevant E2 enzyme (e.g., group IV E2s like SlUBC32/33/34 for plant immunity studies) and continue incubation for additional 5-15 minutes [35].

- Reaction Termination: Add non-reducing Laemmli buffer (lacking β-mercaptoethanol or DTT).

- Electrophoresis: Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE (6-12% gradient gels) without boiling samples.

- Detection: Transfer to PVDF membrane and immunoblot with anti-ubiquitin antibodies. E1~Ub and E2~Ub thioester complexes appear as higher molecular weight bands that disappear upon DTT treatment.

Technical Notes: The adenylation and thioesterification functions of E1 enzymes involve two intricately connected reactions: ATP hydrolysis coupled with ubiquitin activation, followed by formation of a high-energy E1~ubiquitin thioester linkage, and subsequent transfer to E2 catalytic cysteine [35]. Include DTT-treated controls (50 mM final concentration) to confirm thioester linkage specificity.

Visualization of Ubiquitination Cascade and Assay Workflows

The Ubiquitination Cascade and E1 Function

Diagram 1: The ubiquitination cascade initiated by E1 enzyme. The E1 enzyme activates ubiquitin through ATP-dependent adenylation, forms a thioester bond with ubiquitin, and transfers it to E2 conjugating enzymes, ultimately leading to substrate ubiquitination via E3 ligases [35] [36].

UbiReal Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: UbiReal assay workflow using fluorescence polarization. The assay monitors the increase in fluorescence polarization as fluorescently-labeled ubiquitin transitions from free diffusion to being covalently bound in the E1~Ub thioester complex, enabling real-time monitoring of ubiquitin activation and transfer [36].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for E1 Enzyme Activity Assays

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Assays | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzymes | Human UBA1, UBA6, Arabidopsis AtUBA1/2, Tomato SlUBA1/2 | Catalyze ubiquitin activation & thioester formation [35] [27] [37] | Species-specific studies, differential E2 charging |

| E2 Enzymes | UBE2D3, UBE2L3, UBE2N, Tomato group IV E2s (SlUBC32/33/34) | Accept ubiquitin from E1, determine pathway specificity [35] [10] [36] | E1-E2 pairing studies, pathway characterization |

| Ubiquitin Variants | Fluorescein-Ub (F-Ub), TAMRA-Ub (T-Ub), Mutant Ub (K0, K27-only) | E1 substrates for activity monitoring, chain type specificity [10] [36] | FP assays, mechanism studies, chain linkage analysis |

| E1 Inhibitors | TAK-243 (UBA1 inhibitor), Pevonedistat (NAE inhibitor), PYR-41 | Specific E1 inhibition for control experiments & therapeutic studies [27] [37] | Assay validation, drug discovery, pathway modulation |

| Detection Reagents | Anti-ubiquitin antibodies, Fluorescence plate readers, SDS-PAGE systems | Detect ubiquitin conjugates & thioester complexes [35] [10] | All assay formats, endpoint detection |

The expanding toolkit for monitoring E1 enzyme activity and thioesterification provides researchers with complementary approaches spanning from traditional biochemical methods to sophisticated real-time monitoring systems. The UbiReal platform offers distinct advantages for high-throughput screening and kinetic studies, while established thioester assays remain valuable for direct confirmation of covalent intermediate formation. The emerging understanding of differential E2 charging by E1 isoforms across species—from tomato SlUBA1/SlUBA2 with their distinct efficiencies for group IV E2s to human UBA1 and UBA6 with their unique E2 preferences—highlights the importance of enzyme and substrate selection when designing experiments [35] [37]. As research continues to unravel the complexities of E1 biology in health and disease, these assay technologies will play an increasingly vital role in validating new therapeutic targets and developing precision interventions for conditions ranging from VEXAS syndrome to various cancers.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism for protein homeostasis in eukaryotic cells, controlling the stability, activity, and localization of countless proteins. At the apex of the ubiquitination cascade are ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), which initiate the process of ubiquitin transfer to downstream substrates. In humans, two ubiquitin E1 enzymes exist—UBA1 (also known as UBE1) and UBA6—with UBA1 responsible for activating the vast majority (>99%) of cellular ubiquitin [34]. The E1 enzyme mechanism involves a conserved series of steps: first, the E1 binds MgATP and ubiquitin, catalyzing ubiquitin C-terminal acyl-adenylation; second, the catalytic cysteine in the E1 attacks the ubiquitin-adenylate to form a high-energy thioester bond [15]. This activated ubiquitin is then transferred to ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), which subsequently cooperate with ubiquitin ligases (E3) to modify specific target proteins.

The centrality of E1 enzymes to the UPS makes them attractive therapeutic targets. TAK-243 (previously known as MLN7243) represents the first-in-class inhibitor of ubiquitin-activating enzymes that has progressed to clinical trials for cancer therapy (NCT02045095, NCT03816319) [38] [34]. This compound has emerged as both a valuable tool for probing ubiquitination mechanisms in basic research and a promising therapeutic agent with demonstrated efficacy across multiple disease models. Its development marks a significant advancement over earlier, less specific E1 inhibitors such as PYR-41, which exhibited off-target effects against deubiquitinases and protein kinases [34]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of TAK-243's performance relative to other UPS-targeting agents and details experimental approaches for its application in research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of UPS-Targeting Agents

Mechanism and Specificity Profiles

Table 1: Mechanism of Action Comparison Between UPS-Targeting Agents

| Agent | Primary Target | Mechanistic Action | Key Off-Target Effects | Specificity Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAK-243 | UBA1 (Ubiquitin E1) | Forms TAK-243-Ub adduct, blocking ubiquitin transfer to E2 enzymes [39] | Inhibits UBA6, NAE, and SAE at higher concentrations [34] | High specificity for ubiquitin E1 over other UBL E1s [38] |

| Bortezomib | Proteasome (β5 subunit) | Reversibly inhibits chymotrypsin-like activity of proteasome [38] | Inhibits caspase-like and trypsin-like activities at high concentrations [38] | FDA-approved for multiple myeloma |

| Carfilzomib | Proteasome (β5 subunit) | Irreversibly inhibits chymotrypsin-like activity [38] | Inhibits caspase-like and trypsin-like activities at high concentrations [38] | Reduced peripheral neuropathy vs. bortezomib |

| Ixazomib | Proteasome (β5 subunit) | Reversibly inhibits chymotrypsin-like activity [38] | Shorter recovery half-life (<4 hours) after removal [38] | Oral bioavailability |

| PYR-41 | UBA1 (Ubiquitin E1) | Blocks ubiquitin-thioester formation [40] | Inhibits deubiquitinases and protein kinases [34] | First-generation E1 inhibitor (research tool) |

Therapeutic Efficacy and Selectivity

Table 2: Therapeutic Performance Across Disease Models

| Disease Model | TAK-243 Efficacy | Proteasome Inhibitor Efficacy | Key Resistance Mechanisms | Therapeutic Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutaneous SCC | Effective against bortezomib-resistant cells [38] | Variable pattern of sensitivity/resistance [38] | Low UBA1 expression increases TAK-243 susceptibility [38] | Greater selectivity with pulse dosing [38] |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer | Tumor regression in PDX models; reduces metastasis [41] | Limited data in search results | SLFN11 expression inversely correlates with sensitivity [42] | Order of magnitude greater sensitivity vs. normal cells [41] |

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Sensitivity identified through CRISPR screens [43] | Limited data in search results | ABCB1 transporter mediates efflux [42] | Research ongoing |

| Cystic Fibrosis (F508del) | Boosts elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor efficacy [34] | Ineffective as monotherapy [34] | Limited data in search results | Improves rescue of rare misfolded mutants [34] |

| Toxoplasma gondii | Inhibits parasite ubiquitination [39] | Limited data in search results | Limited data in search results | Selective inhibition of TgUAE1 vs. host [39] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Primary Mechanism of Ubiquitin Activation Inhibition

The inhibition of ubiquitin activation by TAK-243 occurs through a well-characterized mechanism. TAK-243 specifically targets the UBA1 enzyme, forming a covalent adduct with ubiquitin (TAK-243-Ub) that blocks the transfer of activated ubiquitin to E2 conjugating enzymes [39]. This mechanism effectively shuts down the majority of cellular ubiquitination events, as UBA1 is responsible for charging over 99% of cellular ubiquitin [34]. The compound exhibits high specificity for ubiquitin E1 enzymes over other ubiquitin-like protein (UBL) E1s, though at higher concentrations it can also inhibit UBA6, NEDD8 E1-activating enzyme (NAE), and the SUMO-activating enzyme (SAE) [34].

Downstream Cellular Consequences

The inhibition of UBA1 by TAK-243 triggers profound cellular stress responses that ultimately lead to cell death, particularly in malignant cells. The primary signaling pathway can be visualized as follows:

Figure 1: TAK-243-induced signaling pathway leading to apoptosis. Inhibition of UBA1 triggers ER stress and the unfolded protein response, culminating in ATF4-mediated NOXA upregulation and apoptosis. c-MYC expression enhances ATF4 activation [41].

The molecular pathway illustrated above demonstrates how TAK-243 inhibition leads to apoptotic cell death. Key steps include:

- UBA1 Inhibition: TAK-243 forms a covalent adduct with ubiquitin, blocking its transfer to E2 enzymes [39]

- Ubiquitination Blockade: Global disruption of protein ubiquitination occurs, affecting numerous cellular processes

- ER Stress Induction: Disruption of protein homeostasis leads to endoplasmic reticulum stress [44] [41]

- UPR Activation: The unfolded protein response is triggered as a compensatory mechanism

- PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 Axis: PERK activation results in eIF2α phosphorylation and selective translation of ATF4 [41]

- NOXA Induction: ATF4 transactivates the pro-apoptotic protein NOXA [41]

- Apoptotic Cell Death: NOXA induction triggers programmed cell death [41]

Notably, c-MYC expression correlates with TAK-243 sensitivity and cooperates with TAK-243 to induce stress response and cell death [41]. This pathway is particularly pronounced in cancer cells with high c-MYC expression, explaining the selective toxicity toward certain malignancies.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

In Vitro Assessment of E1 Inhibition

Ubiquitin Thioesterification Assay: This fundamental assay evaluates the formation of ubiquitin-E1 thioester complexes, which is the primary biochemical activity inhibited by TAK-243.

- Reagents: Purified E1 enzyme (UBA1), ubiquitin, ATP, reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl₂), DTT, TAK-243 in DMSO [39]

- Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixtures containing 100 nM UBA1, 5 μM ubiquitin, and 2 mM ATP in reaction buffer

- Add TAK-243 across a concentration range (typically 0.1 nM - 10 μM)

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes

- Split reactions: add DTT (final 10 mM) to one set, keep the other set without DTT

- Analyze by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and western blot with anti-ubiquitin antibody [39]

- Expected Results: Without DTT, a high molecular weight band (~140 kDa) representing the UBA1-ubiquitin thioester complex should be visible in controls but diminished in TAK-243-treated samples. DTT treatment eliminates this band due to thioester reduction [39].

E1-to-E2 Ubiquitin Transfer Assay: This assay evaluates the downstream consequences of E1 inhibition on ubiquitin transfer to E2 enzymes.

- Reagents: Purified UBA1, E2 enzyme (e.g., Cdc34), ubiquitin, ATP, reaction buffer, TAK-243 [39]

- Procedure:

- Set up reaction mixtures with UBA1, ubiquitin, and ATP as above

- Include relevant E2 enzyme (e.g., 1 μM Cdc34)

- Treat with TAK-243 across concentration gradient

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes

- Analyze by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and western blot with anti-ubiquitin antibody [39]

- Expected Results: Successful ubiquitin transfer to E2 will produce a band corresponding to ubiquitin-E2 complex (~40 kDa) in control samples, which should be reduced in TAK-243-treated samples in a concentration-dependent manner [39].

Cellular Efficacy Assessment

Cell Viability and Apoptosis Assays: These assays evaluate the functional consequences of E1 inhibition in cellular models.

- Reagents: Cell culture media, MTT reagent or alternative viability dye, Annexin V/PI staining kit, TAK-243 [38] [41] [42]

- Procedure:

- Seed cells at appropriate density (e.g., 5,000 cells/well in 96-well plates)

- After 24 hours, treat with TAK-243 concentration series (typically 1 nM - 10 μM)

- For viability: after 72 hours, add MTT and measure formazan formation [42]

- For apoptosis: after 24-48 hours, harvest cells and stain with Annexin V/PI for flow cytometry [41]

- For clonogenic assays: treat cells for 24 hours, then re-plate at low density and count colonies after 7-14 days [41]

- Expected Results: Cancer cell lines typically show IC50 values in the nanomolar range, with normal cells exhibiting higher resistance [41]. Apoptosis induction should correlate with NOXA upregulation [41].

Western Blot Analysis of Pathway Activation: This method confirms target engagement and downstream pathway modulation.

- Reagents: RIPA buffer, protease and phosphatase inhibitors, SDS-PAGE equipment, antibodies against ubiquitin, UBA1, ATF4, NOXA, PARP cleavage, γH2AX [41] [34]

- Procedure:

- Expected Results: Reduced polyubiquitinated species, increased ATF4 and NOXA protein levels, and PARP cleavage indicating apoptosis [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for E1 Inhibition Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Inhibitors | TAK-243/MLN7243, PYR-41, NSC624206 | Mechanistic studies, therapeutic efficacy assessment | TAK-243 has superior specificity; PYR-41 has off-target effects [40] [34] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, Ixazomib | Comparative studies of UPS inhibition | Different specificity profiles and recovery half-lives [38] |

| Cell Lines | TNBC models (BT-549, MDA-MB-468), cSCC lines, AML lines | Disease-specific efficacy assessment | Varying sensitivity based on c-MYC status and UBA1 expression [38] [41] |

| Antibodies | Anti-ubiquitin, anti-UBA1, anti-ATF4, anti-NOXA, anti-cleaved PARP | Pathway analysis and target engagement verification | Essential for validating mechanism of action [41] |

| ABCB1 Modulators | Tepotinib, CRISPR/Cas9 ABCB1 knockout systems | MDR resistance studies | ABCB1 mediates TAK-243 efflux; knockout reverses resistance [42] |