Ubiquitin Code: Decoding the Molecular Nexus of DNA Repair and Immune Signaling in Disease and Therapy

This article synthesizes current research on ubiquitination, an essential post-translational modification that acts as a central regulatory node connecting DNA damage repair with immune response pathways.

Ubiquitin Code: Decoding the Molecular Nexus of DNA Repair and Immune Signaling in Disease and Therapy

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on ubiquitination, an essential post-translational modification that acts as a central regulatory node connecting DNA damage repair with immune response pathways. We explore the foundational mechanisms by which diverse ubiquitin chain topologies—including K48-linked proteolysis, K63-linked signaling scaffolds, and linear ubiquitination—orchestrate cellular homeostasis, from maintaining genomic integrity to directing innate and adaptive immunity. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review further examines cutting-edge methodological approaches for investigating ubiquitin networks, discusses challenges in therapeutic targeting of ubiquitin system enzymes, and validates key targets through comparative analysis of preclinical and clinical data. The integration of these insights highlights the immense potential of targeting the ubiquitin system to develop novel treatments for cancer, inflammatory diseases, and immune disorders.

The Ubiquitin Code: Molecular Mechanisms Linking Genome Integrity and Immune Homeostasis

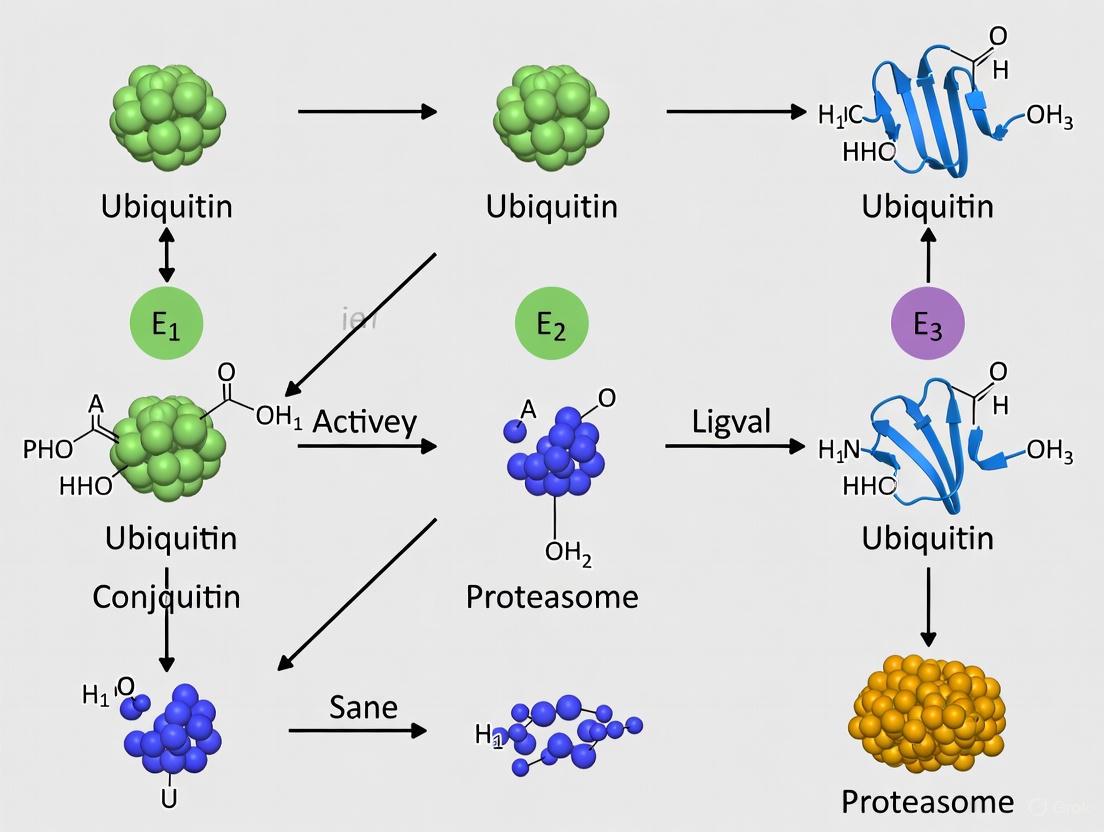

Ubiquitination represents a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes, with particular significance in DNA repair and immune response pathways. This enzymatic process involves a precise cascade mediated by ubiquitin-activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligating (E3) enzymes that collectively coordinate the attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins. The complexity of ubiquitination extends beyond simple protein degradation, as different ubiquitin chain topologies—linked through specific lysine residues or the N-terminus of ubiquitin—create distinct molecular codes that determine diverse functional outcomes. This technical review examines the core mechanisms of the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade, details the structural and functional diversity of ubiquitin chain architectures, and discusses experimental methodologies for investigating ubiquitination, with special emphasis on its roles in maintaining genome integrity and regulating immune signaling. The growing understanding of ubiquitination networks continues to reveal novel therapeutic targets for cancer and other diseases, particularly through the development of targeted inhibitors against specific components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Ubiquitin is a small, 76-amino acid regulatory protein that is highly conserved across eukaryotic organisms and is expressed in most tissues [1]. The ubiquitination process involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins, which subsequently influences their stability, activity, localization, or interactions [1] [2]. This post-translational modification employs a hierarchical enzymatic cascade consisting of E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligating) enzymes that work sequentially to transfer ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins [3] [2]. The human genome encodes two E1 enzymes, approximately 40 E2 enzymes, and an estimated 500-1000 E3 enzymes, providing both specificity and versatility to the ubiquitination system [4].

The functional consequences of ubiquitination are determined by the pattern of ubiquitin modification. Monoubiquitination (attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule) can alter protein localization and activity, while polyubiquitination (formation of ubiquitin chains) can lead to diverse outcomes depending on the linkage type between ubiquitin molecules [2] [5]. The ubiquitin code is further complicated by the fact that ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1), all of which can serve as linkage points for polyubiquitin chain formation [1] [2]. This diversity of chain topologies enables ubiquitination to regulate a vast array of cellular processes, from protein degradation to DNA repair, immune signaling, and beyond [6] [2] [7].

The E1-E2-E3 Enzymatic Cascade

The ubiquitination process proceeds through a three-step enzymatic cascade that ensures precise regulation and substrate specificity:

Step 1: Ubiquitin Activation by E1 Enzymes

The cascade initiates with ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin by E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes. During this process, E1 forms a thioester bond between its active-site cysteine residue and the C-terminal carboxyl group of ubiquitin [3] [2] [4]. This activation step first involves the formation of a ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate, followed by transfer of ubiquitin to the E1 active site cysteine, releasing AMP [1]. The human genome encodes only two E1 enzymes with ubiquitin-activating capability: UBA1 (the primary E1) and UBA6, highlighting the convergence of ubiquitin activation at this initial step [4].

Step 2: Ubiquitin Conjugation by E2 Enzymes

Following activation, ubiquitin is transferred from E1 to the active-site cysteine of an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme through a trans-thioesterification reaction [1] [2]. This step requires the E2 enzyme to bind both the activated ubiquitin and the E1 enzyme [4]. Humans possess approximately 35 E2 enzymes, each characterized by a highly conserved ubiquitin-conjugating catalytic (UBC) fold [1]. While all E2s share this conserved structural domain, different E2 enzymes exhibit significant specificity in their interactions with E3 ligases [2].

Step 3: Ubiquitin Ligation by E3 Enzymes

The final step involves E3 ubiquitin ligases catalyzing the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a specific substrate protein [3] [2]. Most commonly, E3s facilitate the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on the substrate protein [1] [2]. E3 enzymes function as the substrate recognition modules of the system and are capable of interacting with both E2 and substrate [2]. With an estimated 500-1000 members in the human genome, E3 ligases provide the remarkable specificity of the ubiquitination system [4].

E3 ubiquitin ligases are categorized based on their structural domains and mechanisms. The two primary classes are HECT (Homologous to E6-AP C-Terminus) domain E3s and RING (Really Interesting New Gene) domain E3s (and the closely related U-box domain) [1]. HECT domain E3s form an obligate thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate, while RING domain E3s catalyze direct transfer from the E2 enzyme to the substrate [1]. Additionally, multi-subunit E3 complexes such as the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) and the SCF (Skp1-Cullin-F-box protein) complex provide further regulatory complexity [1].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the Ubiquitination Cascade

| Enzyme Type | Number in Humans | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | 2 | Ubiquitin activation via ATP hydrolysis | Forms thioester bond with ubiquitin; initial convergence point |

| E2 (Conjugating) | ~35 | Ubiquitin transfer from E1 to E3/substrate | Contains conserved UBC fold; determines chain topology |

| E3 (Ligating) | 500-1000 | Substrate recognition and ubiquitin transfer | Provides specificity; HECT vs RING mechanistic classes |

Figure 1: The E1-E2-E3 Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade. Ubiquitin is activated by E1 in an ATP-dependent process, transferred to E2, and finally conjugated to substrate proteins via E3 ligases that provide substrate specificity.

Ubiquitin Chain Topologies and Functional Diversity

The structural diversity of ubiquitin chains arises from the ability of ubiquitin itself to be modified at any of its seven lysine residues or its N-terminal methionine, creating polyubiquitin chains with distinct structures and functions [1] [2]. The specific linkage type determines the three-dimensional architecture of the polyubiquitin chain and consequently its biological function.

Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types

K48-linked polyubiquitination represents the best-characterized ubiquitin linkage and typically targets substrate proteins for proteasomal degradation [6] [2]. This linkage forms compact structures that are efficiently recognized by the proteasome [6]. In contrast, K63-linked polyubiquitination adopts an extended "beads-on-a-string" conformation that facilitates protein-protein interactions and functions in various signaling pathways, including DNA damage repair, endocytosis, and immune response activation [6] [4].

The other linkage types have more specialized functions: K6-linked chains participate in DNA damage repair [2]; K11-linked chains regulate cell cycle progression and trafficking events [2]; K27-linked chains mediate mitochondrial autophagy [2]; K29-linked chains are involved in proteasomal degradation under specific conditions [2]; K33-linked chains function in protein trafficking [2]; and M1-linked linear chains play crucial roles in NF-κB signaling and inflammatory responses [1] [2].

Table 2: Ubiquitin Chain Topologies and Their Biological Functions

| Linkage Type | Structural Features | Primary Functions | Cellular Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Compact structure | Proteasomal degradation | Cell cycle, protein turnover |

| K63 | Extended, flexible chain | Signaling scaffold | DNA repair, inflammation, endocytosis |

| K11 | Mixed compact/extended | Proteasomal degradation | Cell cycle regulation, ERAD |

| K27 | Not fully characterized | Mitochondrial autophagy | Quality control, metabolism |

| K29 | Not fully characterized | Proteasomal degradation | Stress response |

| K33 | Not fully characterized | Protein trafficking | Vesicular transport |

| K6 | Not fully characterized | DNA damage response | Genome maintenance |

| M1 (Linear) | Linear chain assembly | NF-κB signaling | Immune and inflammatory responses |

Functional Consequences in DNA Repair and Immune Signaling

In the context of DNA damage response, ubiquitination plays critical roles in coordinating repair pathway choice and efficiency. For example, K63-linked ubiquitination creates platforms that recruit DNA repair proteins to sites of damage [6] [7]. Additionally, monoubiquitination of histone H2AX (γH2AX) by UBE2T/RNF8 accelerates damage detection in hepatocellular carcinoma, while RNF40-generated H2Bub1 recruits the FACT complex to relax nucleosomes, facilitating DNA repair [7].

The ubiquitin system also profoundly regulates immune responses through multiple mechanisms. K63-linked ubiquitination of key signaling molecules in pattern recognition receptor pathways (such as TLR, RLR, and STING-dependent signaling) promotes the activation of NF-κB and interferon regulatory factors, thereby initiating anti-viral and inflammatory responses [2] [7]. Furthermore, ubiquitination regulates immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-L1, whose stability is controlled by ubiquitin-mediated degradation [8].

The plasticity of ubiquitin chain configurations allows for dynamic regulation of these processes. Radiation, for instance, dynamically reprograms ubiquitin signaling by altering chain formation, enabling cancer cells to strategically manipulate K63-linked chains to stabilize DNA repair factors while concurrently inhibiting K48-mediated degradation of survival proteins [7].

Experimental Methods for Investigating Ubiquitination

Advancements in methodological approaches have been crucial for elucidating the complexity of ubiquitination pathways. Several key techniques have enabled researchers to identify ubiquitination sites, quantify changes in ubiquitination, and characterize ubiquitin chain architectures.

Ubiquitin Remnant Profiling (Di-Glycine Capture)

This mass spectrometry-based approach has emerged as the gold standard for proteome-wide identification of ubiquitination sites [5] [9]. The method exploits the fact that tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins leaves a di-glycine remnant (∼114 Da mass shift) from the C-terminus of ubiquitin covalently attached to the previously modified lysine [9]. Monoclonal antibodies specifically recognizing this di-glycine adduct (such as the GX41 antibody) are used to enrich for modified peptides from complex protein digests, followed by LC-MS/MS analysis for identification and quantification [9].

The ubiquitin remnant profiling workflow typically involves: (1) protein extraction from cells or tissues; (2) proteolytic digestion with trypsin; (3) immunoaffinity enrichment of di-glycine-modified peptides; (4) LC-MS/MS analysis; and (5) database searching with inclusion of the di-glycine modification (∼114.0429 Da) as a variable modification on lysine [9]. This approach can be combined with quantitative proteomics methods such as SILAC (stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture) or TMT (tandem mass tag) labeling to investigate dynamic changes in ubiquitination in response to cellular perturbations like DNA damage [9].

One limitation of this method is that it cannot distinguish between ubiquitination and modification by other ubiquitin-like proteins (such as NEDD8 and ISG15) that also generate di-glycine remnants after tryptic digestion [9]. However, control experiments have demonstrated that >94% of di-glycine-modified peptides identified in standard cell lines are genuine ubiquitin remnants [9].

Activity-Based Probes for Ubiquitin Enzymes

Cascading activity-based probes such as UbDha have been developed to monitor catalysis along the E1-E2-E3 reaction pathway [10]. These probes function similarly to native ubiquitin—upon ATP-dependent activation by E1, they travel downstream to E2 and subsequently E3 enzymes through sequential trans-thioesterifications [10]. Unlike native ubiquitin, however, these probes contain electrophilic traps that react irreversibly with active-site cysteine residues of target enzymes, enabling their detection and characterization [10].

This methodology allows for: (1) profiling of active ubiquitin-modifying enzymes under different physiological conditions; (2) monitoring enzymatic activity in living cells; and (3) structural studies of enzyme-probe interactions [10]. The approach is diversifiable to ubiquitin-like modifiers and provides novel tools to interrogate ubiquitin and Ubl cascades.

Chain Linkage-Specific Analysis

To decipher the complexity of ubiquitin chain architectures, researchers have developed linkage-specific binders including antibodies, affimers, and TUBEs (tandem ubiquitin-binding entities) that recognize particular ubiquitin linkage types [7] [9]. These tools enable enrichment of proteins modified by specific types of ubiquitin chains, followed by proteomic analysis to identify the modified proteins and their biological contexts [9].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Remnant Profiling. This mass spectrometry-based approach enables proteome-wide identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites through specific enrichment of di-glycine-modified peptides.

Research Reagent Solutions

The investigation of ubiquitination pathways relies on specialized reagents and tools designed to address the unique challenges of studying this complex post-translational modification.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Di-Glycine Remnant Antibodies (e.g., GX41) | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitin remnant peptides | Ubiquitin remnant profiling; site identification |

| Activity-Based Probes (e.g., UbDha) | Irreversible trapping of active ubiquitin enzymes | Profiling E1-E2-E3 activities; mechanistic studies |

| Linkage-Specific Binders (TUBEs, antibodies) | Selective recognition of specific ubiquitin chain types | Chain topology analysis; linkage-specific enrichment |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib, MG132) | Inhibition of proteasomal degradation | Stabilization of ubiquitinated proteins; pathway analysis |

| DUB Inhibitors | Selective inhibition of deubiquitinating enzymes | Investigation of ubiquitination dynamics; therapeutic探索 |

| Recombinant E1/E2/E3 Enzymes | Reconstitution of ubiquitination cascades | In vitro ubiquitination assays; mechanistic studies |

Therapeutic Targeting of Ubiquitination Pathways

The central role of ubiquitination in regulating cellular processes, combined with its frequent dysregulation in diseases, has made it an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. Several classes of drugs targeting different components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system have been developed, with some achieving clinical success.

Proteasome inhibitors represent the most clinically advanced class of UPS-targeting therapeutics. Bortezomib (Velcade) was the first proteasome inhibitor approved by the FDA for the treatment of multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma [4]. This boronic acid derivative functions by reversibly binding to the catalytic site of the 26S proteasome [4]. Carfilzomib (Kyprolis), a second-generation proteasome inhibitor, derives from the natural product epoxomicin and has shown efficacy in bortezomib-resistant multiple myeloma [4]. Additional proteasome inhibitors in clinical development include marizomib, ixazomib, and CEP-18770 [4].

E1 enzyme inhibitors have also been explored, though their development is more challenging due to the limited number of E1 enzymes and potential toxicity concerns. Nevertheless, MLN7243 (targeting UBA1) has entered Phase I/II clinical trials [4]. The related compound MLN4924 inhibits the NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE), thereby specifically affecting the activity of Cullin-RING ligases, a major class of E3 ubiquitin ligases [4].

E2 enzyme inhibitors represent an emerging area, with compounds such as Leucettamol A (targeting the Ubc13-Uev1A interaction) and CC0651 (inhibiting Cdc34) showing promise in preclinical studies [4]. These inhibitors typically target protein-protein interactions required for E2 function or specific catalytic activities.

E3 ligase modulators have gained significant attention due to the potential for greater specificity. Notable examples include nutlin-3a and RG7112, which disrupt the interaction between the E3 ligase MDM2 and the tumor suppressor p53, leading to p53 stabilization and activation of apoptosis in cancer cells [4]. Several MDM2 inhibitors have advanced to clinical trials. Additionally, immunomodulatory drugs such as thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide have been shown to target the CRL4CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to selective degradation of specific substrate proteins in multiple myeloma [4].

The growing understanding of ubiquitination mechanisms has also enabled the development of novel therapeutic modalities such as PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) that harness the ubiquitin system to selectively degrade target proteins [7]. These bifunctional molecules simultaneously bind to a target protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase, resulting in ubiquitination and degradation of the target [7]. Radiation-responsive PROTAC platforms are also emerging, including radiotherapy-triggered PROTAC (RT-PROTAC) prodrugs that are activated by tumor-localized X-rays to degrade specific oncoproteins [7].

The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade and the diverse topology of ubiquitin chains constitute a sophisticated regulatory system that governs virtually all aspects of cellular function. The hierarchical nature of the enzyme cascade—with two E1s, approximately 35 E2s, and hundreds of E3s—provides both efficiency and remarkable specificity in substrate selection. The structural diversity of ubiquitin chains, linked through different lysine residues or the N-terminal methionine, creates a complex ubiquitin code that determines functional outcomes ranging from proteasomal degradation to activation of signaling pathways.

In the context of DNA repair and immune response pathways, ubiquitination serves as a master regulator that coordinates complex cellular decisions. Through mechanisms such as K63-linked ubiquitination in DNA damage signaling and M1-linear ubiquitination in NF-κB activation, the ubiquitin system ensures appropriate cellular responses to genomic and environmental challenges. The development of sophisticated experimental methods, particularly ubiquitin remnant profiling and activity-based probes, has dramatically advanced our understanding of these processes.

The therapeutic targeting of ubiquitination pathways has already yielded clinically successful drugs, particularly proteasome inhibitors for hematological malignancies. The ongoing development of more specific agents targeting E2 and E3 enzymes, along with innovative approaches such as PROTACs, promises to expand the therapeutic applications of ubiquitin manipulation. As research continues to decipher the complexity of the ubiquitin code, new opportunities will emerge for precisely modulating ubiquitination pathways in disease contexts, particularly in cancer and disorders of immune regulation.

The faithful repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) is fundamental to maintaining genomic integrity and preventing cellular transformation. The cellular response to these lethal lesions is orchestrated by a sophisticated network of post-translational modifications, among which ubiquitin signaling has emerged as a central regulatory mechanism. Similar to phosphorylation, ubiquitination creates a diverse array of molecular signals that control the recruitment, activity, and stability of DNA repair factors at damage sites [6] [11]. This review examines how the ubiquitin system—comprising writers (E3 ligases), erasers (deubiquitinating enzymes), and readers (ubiquitin-binding domains)—orchestrates the complex decision-making processes that govern DSB repair pathway choice, functionality, and termination.

The strategic importance of ubiquitin signaling in the DNA damage response (DDR) is underscored by its involvement in human diseases linked to genomic instability, including various cancer syndromes [12] [13]. Understanding the mechanistic basis of ubiquitin-dependent regulation in DSB repair not only advances fundamental knowledge but also offers promising therapeutic opportunities for cancers characterized by defective DNA repair pathways [12] [14].

The Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-Like Conjugation Systems

Principles of Ubiquitin Conjugation

Ubiquitylation is a multistep enzymatic process that involves the sequential action of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes [11] [13]. This cascade results in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin—a highly conserved 76-amino acid protein—to target substrates via an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on the substrate [11]. The human genome encodes approximately 600 E3 ligases, which provide substrate specificity and are categorized into two main classes: RING (really interesting new gene) and HECT (homologous to E6AP carboxyl terminus) domain-containing enzymes [15] [16].

The remarkable diversity of ubiquitin signaling stems from the ability to form different ubiquitin chain architectures. Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine, all of which can participate in chain formation [11] [15]. These distinct linkage types confer different structures and functions—K48-linked chains primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains typically serve non-proteolytic roles in signaling and protein recruitment [6] [11].

Table 1: Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Functions in DNA Damage Response

| Linkage Type | Chain Structure | Primary Functions | Key Roles in DSB Repair |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Compact conformation [6] | Proteasomal degradation [11] | Regulation of protein stability (e.g., p53) [13] |

| K63-linked | Extended, "beads-on-a-string" [6] | Non-degradative signaling [11] | Recruitment of repair factors (BRCA1, 53BP1) [12] [15] |

| K6-linked | Not well characterized | DNA repair [11] | Involved in Fanconi anemia pathway [11] |

| K11-linked | Unique conformation [11] | Cell cycle regulation [11] | Potential role in cell cycle checkpoints |

| K27-linked | Not well characterized | Non-canonical signaling [12] | DNA damage signaling [12] |

| Linear/M1-linked | Extended structure | NF-κB signaling, inflammation | Emerging roles in genome stability |

SUMO and Other Ubiquitin-Like Modifiers

Beyond ubiquitin, cells employ additional ubiquitin-like modifiers (UBLs) including SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier), which follows a similar enzymatic conjugation cascade but utilizes distinct E1 and E2 enzymes [11] [16]. Mammals express three major SUMO isoforms (SUMO1, SUMO2, and SUMO3) that can be conjugated to substrates through a consensus motif (ΨKXE/D) [11]. SUMOylation has been implicated in various aspects of genome maintenance, with recent evidence highlighting extensive crosstalk between ubiquitin and SUMO in the DSB response [12] [17].

Ubiquitin-Dependent Signaling at DNA Double-Strand Breaks

Hierarchical Assembly of the Ubiquitin Signaling Cascade

The initiation of ubiquitin signaling at DSBs begins with the activation of the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase, which phosphorylates the histone variant H2AX on serine 139 (generating γ-H2AX) within minutes of damage detection [6] [15]. This phosphorylation event spreads over megabase domains flanking the break and serves as a binding platform for the mediator protein MDC1, which in turn recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF8 through phospho-dependent interactions [12] [15].

RNF8 catalyzes the K63-linked ubiquitination of histone H1 and L3MBTL2, creating a landing platform for a second E3 ligase, RNF168 [12] [15]. RNF168 then monoubiquitinates histones H2A and H2AX at lysine 13/15, which is subsequently extended into K63-linked chains [15]. This RNF8/RNF168-dependent ubiquitin platform serves as a critical recruitment signal for downstream DNA repair factors including 53BP1 and the BRCA1-A complex [12] [18].

Diagram 1: Hierarchical ubiquitin signaling cascade at DNA double-strand breaks. The pathway initiates with ATM activation and progresses through sequential recruitment of E3 ubiquitin ligases that modify chromatin to create binding platforms for downstream effectors.

Ubiquitin-Binding Domains as Decoders of the Ubiquitin Code

The information encoded in ubiquitin modifications is decoded by specialized ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) present in DNA repair proteins [6] [14]. These domains recognize specific features of ubiquitin chains, including linkage type and length. For instance, the tandem UIM domains of RAP80 exhibit remarkable specificity for K63-linked ubiquitin chains, enabling recruitment of the BRCA1-A complex to DSB sites [12]. Similarly, 53BP1 utilizes a ubiquitination-dependent recruitment (UDR) motif that directly binds RNF168-ubiquitylated H2A, facilitating its accumulation at breaks [12].

The low affinity of individual UBDs for ubiquitin is strategically overcome through multiple mechanisms, including the presence of tandem UBDs within a single protein and the clustering of UBD-containing proteins within multi-protein complexes [14]. This avidity-based recognition system allows for sensitive detection of ubiquitin signals while maintaining the reversibility essential for dynamic regulation.

Regulation of DSB Repair Pathway Choice by Ubiquitin

The Balance Between NHEJ and Homologous Recombination

One of the most critical decisions following DSB formation is the choice between two major repair pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) [18] [15]. NHEJ promotes direct ligation of broken DNA ends throughout the cell cycle but is error-prone, while HR requires a sister chromatid template and is restricted to S/G2 phases but is largely error-free [12] [14]. Ubiquitin signaling plays a pivotal role in regulating this pathway choice, primarily through the opposing actions of 53BP1 (promoting NHEJ) and BRCA1 (promoting HR) [15].

The recruitment of 53BP1 to DSBs requires recognition of RNF168-dependent H2A ubiquitination (K15ub) combined with H4K20 methylation [12] [15]. Once recruited, 53BP1 interacts with RIF1 and the shieldin complex to inhibit DNA end resection—the nucleolytic processing of DNA ends that represents the committed step for HR [15]. In contrast, BRCA1 promotes end resection through the recruitment and activation of nucleases such as CtIP, effectively opposing 53BP1 function and directing repair toward HR [15].

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of DSB repair pathway choice. The balance between NHEJ and HR is controlled by opposing ubiquitin-mediated recruitment of 53BP1 (promoting NHEJ) and BRCA1 (promoting HR), which differentially regulate the critical step of DNA end resection.

Regulation by Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs)

The ubiquitin landscape at DSBs is dynamically regulated by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin modifications, providing an essential counterbalance to E3 ligase activity [18] [17]. Multiple DUB families have been implicated in the DSB response, including ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), and JAMM motif zinc metalloproteases [15].

Specific DUBs such as USP51, USP3, and BRCC36 have been shown to target RNF168-dependent H2A ubiquitination at lysine 13/15, thereby attenuating 53BP1 recruitment and influencing repair pathway choice [15]. The opposing actions of E3 ligases and DUBs create a dynamic equilibrium that allows precise control over the timing and extent of ubiquitin signaling, ensuring appropriate repair outcomes.

Table 2: Key Deubiquitinating Enzymes in the DNA Double-Strand Break Response

| DUB | Family | Target(s) | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP51 | Ubiquitin-specific protease | H2A K13/15 ub [15] | Removes RNF168-dependent ubiquitin, regulates 53BP1 recruitment |

| USP3 | Ubiquitin-specific protease | H2A K13/15 ub [15] | Counteracts RNF8/RNF168 signaling, loss increases IR sensitivity |

| BRCC36 | JAMM metalloprotease | H2AX ubiquitination [15] | Opposes RNF8-mediated ubiquitination, enhances radiosensitivity |

| USP11 | Ubiquitin-specific protease | PALB2, H2A [15] | Promotes HR by stabilizing BRCA1-PALB2 interaction |

| USP44 | Ubiquitin-specific protease | H2A ubiquitination [15] | Regulates histone ubiquitination at DSBs |

Experimental Approaches and Research Tools

Methodologies for Studying Ubiquitin in DNA Repair

Advances in our understanding of ubiquitin signaling in the DDR have been driven by the development of sophisticated experimental methodologies spanning genetics, proteomics, and biochemistry [14]. Genetic screens using RNA interference (RNAi) and, more recently, CRISPR-Cas9 have identified numerous components of the ubiquitin system as regulators of DNA repair [14]. However, technical challenges such as off-target effects in RNAi screens have necessitated rigorous validation approaches [14].

Proteomic techniques have been particularly valuable for mapping ubiquitination sites and identifying ubiquitin-dependent protein interactions. Quantitative mass spectrometry approaches have enabled system-wide analyses of ubiquitylation dynamics in response to DNA damage, revealing the astonishing complexity of the ubiquitin code [12] [14]. Additionally, biochemical reconstitution of ubiquitination events using purified components has provided mechanistic insights into the specificity and regulation of E3 ligases and DUBs [14].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Studying Ubiquitin in DNA Repair

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Applications and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Approaches | Genome-wide RNAi/CRISPR screens [14] | Identification of novel regulators of ubiquit-dependent repair |

| Proteomic Methods | Quantitative mass spectrometry [12] [14] | System-wide analysis of ubiquitination sites and dynamics |

| Biochemical Tools | Activity-based probes for DUBs [14] | Profiling deubiquitinating enzyme activities and specificities |

| Visualization Techniques | Immunofluorescence (IRIF) [6] | Spatial and temporal analysis of repair factor recruitment |

| Structural Biology | NMR, X-ray crystallography [6] | Determination of ubiquitin chain structures and UBD interactions |

| Chemical Biology | Proteasome inhibitors, DUB inhibitors [13] | Dissecting specific ubiquitin pathway functions |

Visualization and Monitoring Techniques

The visualization of DNA repair factors at DSBs through immunofluorescence microscopy (detecting ionizing radiation-induced foci, IRIF) has been instrumental in characterizing the ubiquitin-dependent recruitment cascade [6]. This approach revealed the suprastoichiometric accumulation of repair proteins at break sites, with individual DSBs recruiting up to 1,000 molecules of each repair protein [6]. Live-cell imaging techniques have further enhanced our ability to monitor the dynamic assembly and disassembly of repair complexes in real time, providing insights into the kinetics of ubiquitin signaling events.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

Dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling factors involved in DSB repair is tightly linked to severe human disorders and cancer predisposition syndromes [12] [13]. For example, epigenetic inactivation of the E3 ligase CHFR has been documented in multiple cancer types, including breast, colorectal, and lung cancers [13]. Similarly, mutations in DUBs such as BRCC36 have been associated with altered DNA damage sensitivity and genomic instability [15].

The mechanistic insights into ubiquitin-dependent DSB repair offer promising therapeutic opportunities for cancers characterized by genetic instability [12] [14]. Several strategies are being explored, including the development of small molecule inhibitors targeting specific E3 ligases or DUBs, as well as synthetic lethal approaches that exploit the differential dependency of cancer cells on specific DNA repair pathways [13] [14]. For instance, cancers deficient in HR repair (such as BRCA-mutant cancers) show heightened sensitivity to PARP inhibitors, and combining these with modulation of ubiquitin pathway components may enhance therapeutic efficacy or overcome resistance [14].

Future research directions will likely focus on deciphering the more complex aspects of the ubiquitin code, including the functions of atypical ubiquitin chains and the extensive crosstalk between ubiquitin and other UBLs [14] [17]. Additionally, understanding how the ubiquitin system integrates with other cellular processes, such as cell cycle regulation and innate immune signaling, will provide a more comprehensive view of its role in maintaining genome stability and cellular homeostasis [14].

Ubiquitin signaling has emerged as a central regulatory mechanism that orchestrates multiple aspects of the DNA double-strand break response, from initial damage recognition to repair pathway choice and termination. The dynamic and reversible nature of ubiquitination, combined with the astounding diversity of ubiquitin chain architectures, provides a sophisticated signaling system that can be precisely tuned to ensure appropriate repair outcomes. Continued elucidation of the complexities of ubiquitin signaling in DNA repair will not only advance our fundamental understanding of genome maintenance mechanisms but also open new avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other diseases associated with genomic instability.

The cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) represents one of the most critical defense mechanisms for maintaining genomic integrity. DSBs are highly deleterious lesions that can lead to chromosomal translocations, genome instability, and malignant transformation if improperly repaired [19]. The DNA damage response (DDR) operates in the context of chromatin, where elaborate signaling pathways coordinate the ordered recruitment of specific factors to damage sites to facilitate repair and activate cell cycle checkpoints [20]. Within this sophisticated network, ubiquitin signaling—particularly histone ubiquitination—has emerged as a central regulatory mechanism that orchestrates the DDR.

Recent advances have illuminated the pivotal role of RNF168, a RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase, as a master regulator of histone ubiquitination at DSB sites [21]. This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms through which RNF168-mediated ubiquitination of H2A and H2AX governs DDR pathway activation and chromatin remodeling. Understanding these processes provides critical insights for therapeutic interventions targeting DNA repair pathways in cancer and other diseases.

The RNF168 Ubiquitin Ligase: Mechanism and Regulation

Molecular Architecture and Functional Domains

RNF168 possesses a modular structure containing distinct functional domains that enable its specific role in the DDR cascade. A key discovery is that RNF168 undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) through an intrinsically disordered region (IDR) spanning amino acids 460-550 [21]. This condensation behavior significantly enhances RNF168's catalytic activity and facilitates its rapid accumulation at DNA break sites.

Mechanism of LLPS-Enhanced Function: The phase separation capacity of RNF168 creates a concentrated microenvironment that promotes efficient ubiquitin transfer. This LLPS is significantly enhanced by K63-linked polyubiquitin chains, establishing a positive feedback loop that amplifies RNF168-mediated signaling at DSB sites [21]. Functionally, LLPS deficiency in RNF168 results in delayed recruitment of critical repair factors 53BP1 and BRCA1, ultimately impairing DSB repair efficiency [21].

The Ubiquitination Cascade

RNF168 operates within a hierarchical ubiquitination cascade initiated by the E3 ligase RNF8, which recruits RNF168 to damage sites [19]. RNF168 then catalyzes the monoubiquitination of histone H2A and its variant H2AX on specific lysine residues, including K13, K15, and K119 [20]. This ubiquitin signaling creates docking platforms for the recruitment of downstream DNA repair factors.

Table 1: Key Histone Ubiquitination Targets in the DNA Damage Response

| Histone Target | Ubiquitination Site | E3 Ubiquitin Ligase | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2A | K13, K15 | RNF168 | Recruitment of 53BP1 and BRCA1 |

| H2AX | K13, K15 | RNF168 | Amplification of damage signaling |

| H2A | K119 | RNF168/BMI1 | Transcriptional silencing at breaks |

| H2A | K127/129 | BRCA1-BARD1 | Promotion of homologous recombination |

Chromatin Remodeling and Repair Pathway Choice

Histone Ubiquitination in the Epigenetic Landscape of DSBs

The pre-existing chromatin conformation significantly influences both DNA damage induction and repair pathway selection. Compacted heterochromatin may physically shield DNA from damage, while simultaneously presenting challenges for repair machinery accessibility [19]. The "prime-repair-restore" model describes how the initial chromatin landscape is remodeled to facilitate damage signaling, followed by restoration of the original epigenetic state after repair completion [19].

RNF168-generated ubiquitin marks function as central components of this repair-associated epigenetic landscape. The RNF8-RNF168 ubiquitination axis promotes two critical chromatin modifications that 53BP1 recognizes in a bivalent mode: H2AK15ub and H4K20me2 [19]. This dual recognition mechanism ensures specific targeting of 53BP1 to DSB sites, where it promotes non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) by limiting DNA end resection.

Crosstalk with Other Post-Translational Modifications

Ubiquitination does not function in isolation but engages in sophisticated crosstalk with other histone modifications to regulate DDR pathway choice:

Ubiquitination and Acetylation: The histone acetyltransferase TIP60 acetylates H2AK15, directly blocking RNF168-mediated ubiquitination at this site and impairing 53BP1 binding [19]. Additionally, TIP60-mediated acetylation of H4K16 physically inhibits 53BP1 binding to H4K20me2, thereby promoting homologous recombination (HR) [20].

Ubiquitination and Methylation: Histone H4K20 methylation provides a binding platform for 53BP1 recruitment [20]. The removal or absence of methylation at H4K20 (H4K20me0) guides repair pathway choice toward HR by creating a binding site for the BRCA1-BARD1 complex [19].

Ubiquitination and Phosphorylation: Phosphorylation of the histone variant H2AX (forming γ-H2AX) by ATM, ATR, and DNA-PKcs represents one of the earliest DDR signaling events [19]. This phosphorylation cascade promotes the recruitment of RNF8, which initiates the ubiquitination signaling that recruits RNF168, creating a feedback loop that amplifies DDR activation [20].

Diagram 1: RNF168-Driven Ubiquitin Signaling Cascade at DSB Sites. The pathway illustrates the sequential recruitment and activation of key DDR factors following DNA damage, culminating in RNF168-mediated histone ubiquitination that directs repair pathway choice.

Advanced Experimental Approaches

Methodologies for Studying RNF168 Function

LLPS Analysis in RNF168 Condensation: To investigate RNF168 phase separation, researchers employ purified RNF168 protein subjected to in vitro condensation assays [21]. The experimental workflow involves:

- Protein Purification: Recombinant RNF168 is expressed and purified using affinity chromatography.

- LLPS Induction: Purified RNF168 is exposed to K63-linked polyubiquitin chains in physiological buffers.

- Imaging and Quantification: Liquid-like condensate formation is visualized by microscopy and quantified for number, size, and dynamics.

- Functional Validation: H2A.X ubiquitination assays are performed to correlate LLPS with catalytic activity enhancement.

DNA Repair Factor Recruitment Kinetics: To assess the functional consequences of RNF168 activity, time-course experiments monitor the recruitment of 53BP1 and BRCA1 to DSB sites [21]:

- DSB Induction: Cells are irradiated or treated with DSB-inducing agents.

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Fixed cells are stained with antibodies against γ-H2AX, 53BP1, and BRCA1 at various time points.

- Image Analysis: Confocal microscopy quantifies fluorescence intensity at damage sites.

- Statistical Comparison: Recruitment kinetics are compared between wild-type and LLPS-deficient RNF168 mutants.

Techniques for Monitoring Histone Ubiquitination

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Sequencing: This approach maps the genomic distribution of ubiquitinated histones and repair factors:

- Crosslink cells and isolate chromatin

- Immunoprecipitate with antibodies specific for H2AK15ub

- Sequence bound DNA fragments

- Analyze enrichment patterns at DSB sites and genome-wide

Comet Assay for DNA Break Detection: The neutral comet assay quantifies genomic DSBs in single cells [22]:

- Embed cells in low-melting-point agarose on microscope slides

- Lyse cells to remove membranes and proteins

- Perform electrophoresis under neutral conditions

- Stain with DNA-binding dye and image by fluorescence microscopy

- Quantify DNA damage using Olive Tail Moment analysis

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of RNF168 LLPS Impact on DSB Repair

| Experimental Parameter | Wild-type RNF168 | LLPS-Deficient RNF168 | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2A.X Ubiquitination | Enhanced by K63-ubiquitin | Significantly reduced | In vitro ubiquitination assay |

| 53BP1 Recruitment | Rapid accumulation (<2h) | Delayed (>4h) | Immunofluorescence microscopy |

| BRCA1 Recruitment | Efficient foci formation | Impaired foci formation | Confocal microscopy quantification |

| DSB Repair Efficiency | High survival rate | Reduced survival | Clonogenic survival assay |

| Phase Separation | Robust condensates | Minimal condensation | In vitro LLPS assay |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Histone Ubiquitination in DDR

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase Inhibitors | RNF168 small molecule inhibitors | Pathway disruption studies | Block specific ubiquitin transfer |

| Ubiquitin Variants | K63-linked ubiquitin chains | LLPS enhancement assays | Promote RNF168 condensation |

| Specific Antibodies | Anti-H2AK15ub, Anti-γH2AX | Damage site visualization | Immunofluorescence detection |

| Cell Line Models | RNF168 knockout cells | Functional rescue experiments | Define pathway requirements |

| Chemical Inhibitors | ATM inhibitors (KU-55933), DNA-PKcs inhibitors (NU7026) [23] | Kinase pathway analysis | Dissect signaling hierarchies |

| LLPS Reporters | RNF168-IDR fusion constructs | Phase separation dynamics | Live imaging of condensates |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The central role of RNF168-mediated ubiquitin signaling in DDR pathway choice presents compelling therapeutic opportunities. Cancer cells with defective HR repair (such as those with BRCA1/2 mutations) depend on NHEJ and alternative repair pathways for survival. Therapeutic strategies targeting RNF168 could potentially sensitize such cancers to DNA-damaging agents by disrupting this compensatory repair mechanism.

Emerging evidence also links RNF168 and histone ubiquitination to immune signaling pathways. In macrophages, DSBs activate a genetic program that promotes inflammasome activation and production of IL-1β and IL-18, with this response being regulated by DDR kinases [23]. This intersection between DNA damage and immune signaling may have significant implications for cancer immunotherapy, particularly in understanding the mechanistic basis of how genomic instability influences antitumor immunity.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Developing specific pharmacological inhibitors of RNF168 catalytic activity

- Elucidating the structural basis of RNF168 LLPS and its regulation

- Investigating the crosstalk between histone ubiquitination and other PTMs in different chromatin contexts

- Exploring the role of RNF168 in immune cell function and tumor microenvironment regulation

The sophisticated experimental approaches outlined in this technical guide provide the foundation for advancing our understanding of histone ubiquitination in DNA repair and developing novel therapeutic strategies that target these pathways in human disease.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing RNF168 Function. The diagram outlines key methodological approaches for investigating RNF168-mediated histone ubiquitination and its functional consequences in DNA double-strand break repair.

The ubiquitin system, a pervasive post-translational modification mechanism, is a critical regulator of innate immune responses. It orchestrates the detection of pathogens by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) and the subsequent induction of inflammatory and antiviral responses [24] [25]. Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of the 76-amino-acid protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins via a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [26] [27]. The process is reversible through the action of deubiquitinases (DUBs), allowing for dynamic control of signaling pathways [24] [25]. The functional outcome of ubiquitination is determined by the topology of the ubiquitin chain. K63-linked and linear (Met1-linked) polyubiquitin chains typically serve as non-degradative scaffolds that facilitate the assembly of signaling complexes, whereas K48-linked polyubiquitin chains predominantly target proteins for proteasomal degradation [26] [25] [28]. This "ubiquitin code" enables precise regulation of PRR pathways, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), the cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS-STING, and inflammasome complexes, ensuring an effective yet balanced immune response to infection [29] [30] [25].

Ubiquitination in Toll-like Receptor (TLR) Signaling

Toll-like receptors are membrane-bound PRRs that sense pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) either at the cell surface or within endosomal compartments [25]. Their signaling primarily transduces signals through the adaptor proteins MyD88 (all TLRs except TLR3) and TRIF (TLR3 and TLR4), culminating in the activation of transcription factors NF-κB and IRF3/7 to induce proinflammatory cytokines and type I interferons (IFNs) [25].

- Key Regulatory Ubiquitination Events: The signaling cascades downstream of TLRs are heavily governed by ubiquitination. The E3 ligase TRAF6 plays a central role: upon recruitment to activated receptors, it catalyzes the formation of K63-linked ubiquitin chains on itself and other proteins, such as NEMO [25]. These chains serve as a platform to recruit and activate the TAK1 kinase complex via ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) present in its subunits. TAK1 then phosphorylates and activates the IKK complex, leading to NF-κB activation [25]. Similarly, the adaptor TRIF recruits RIP1 via RHIM-domain interaction, and K63-linked ubiquitination of RIP1 facilitates the recruitment of TAK1 and NEMO for NF-κB activation [25].

- Negative Regulation: Deubiquitinases provide crucial negative feedback to prevent excessive TLR signaling. For example, A20 (also known as TNFAIP3) dampens NF-κB activation by removing K63-linked ubiquitin chains from RIP1 and other signaling molecules [25] [31]. The Met1-linkage-specific DUB OTULIN hydrolyzes linear ubiquitin chains assembled by the LUBAC complex, thereby fine-tuning inflammatory signaling and cell fate decisions [24].

Table 1: Key Ubiquitin-Related Enzymes in TLR Signaling

| Enzyme Name | Type | Target Protein | Ubiquitin Linkage | Function in Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAF6 | RING E3 Ligase | Itself, NEMO | K63 | Positively regulates NF-κB and MAPK activation [25]. |

| LUBAC | RBR E3 Ligase | NEMO, RIP1 | Linear (Met1) | Positively regulates NF-κB activation [24] [25]. |

| A20 (TNFAIP3) | DUB & E3 Ligase | RIP1 | K63 (DUB activity) | Negatively regulates NF-κB; dual enzyme activity [25] [31]. |

| OTULIN | DUB | Linear ubiquitin chains | Linear (Met1) | Negatively regulates NF-κB by hydrolyzing linear chains [24]. |

Figure 1: Ubiquitin Regulation in TLR Signaling Pathways. K63-linked ubiquitination events are central to the activation of downstream NF-κB and MAPK pathways, while DUBs like A20 and OTULIN provide negative feedback.

Ubiquitination in RIG-I-like Receptor (RLR) Signaling

RLRs, including RIG-I and MDA5, are cytosolic sensors of viral RNA that initiate antiviral innate immunity [29] [25]. Upon ligand binding, they undergo conformational changes and interact with the mitochondrial adaptor protein MAVS (also known as IPS-1, VISA, Cardif), triggering a signaling cascade that leads to the production of type I IFNs [29].

- Sequential Ubiquitination of RIG-I: The activation of RIG-I is a tightly controlled process involving sequential ubiquitination. The E3 ligase Riplet (RNF135) first ubiquitylates RIG-I at K788, which releases its CARD domains from an autorepressed state [29]. Subsequently, TRIM25 and TRIM4 synthesize K63-linked ubiquitin chains on the RIG-I CARD domains (at K172 and K164/172, respectively), facilitating the interaction and aggregation of RIG-I with the downstream adaptor MAVS [29]. Another E3, MEX3C (RNF194), also promotes RIG-I activation through K63-linked ubiquitylation [29].

- Regulation of MDA5 and MAVS: The related RLR MDA5 is similarly regulated by ubiquitin. TRIM65 catalyzes K63-linked polyubiquitylation of MDA5 at K743, promoting its activation [29]. At the level of the mitochondrial adaptor MAVS, TRIM31 and TRIM21 positively regulate signaling. TRIM31 promotes K63-linked polyubiquitylation and aggregation of MAVS, while TRIM21 mediates K27-linked ubiquitylation to enhance TBK1 binding [29]. Negative regulators include RNF5, which targets MAVS for K48-linked degradative ubiquitylation [29].

Table 2: Key Ubiquitin-Related Enzymes in RLR Signaling

| Enzyme Name | Type | Target Protein | Ubiquitin Linkage | Function in Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riplet (RNF135) | RING E3 Ligase | RIG-I | K63 | Initiates RIG-I activation by releasing CARDs [29]. |

| TRIM25 | RING E3 Ligase | RIG-I | K63 | Promotes RIG-I CARD oligomerization and MAVS binding [29]. |

| TRIM65 | RING E3 Ligase | MDA5 | K63 | Positively regulates MDA5 activation [29]. |

| TRIM31 | RING E3 Ligase | MAVS | K63 | Promotes MAVS aggregation and signal transduction [29]. |

| RNF5 | RING E3 Ligase | MAVS | K48 | Negatively regulates signaling by targeting MAVS for degradation [29]. |

Figure 2: Ubiquitin Regulation in RLR Antiviral Signaling. K63-linked ubiquitination is essential for the activation of RIG-I/MDA5 and the MAVS signalosome, while E3 ligases like RNF5 attenuate signaling via K48-linked degradation.

Ubiquitination in the cGAS-STING Signaling Pathway

The cGAS-STING pathway is a key defender against cytosolic DNA from viruses, intracellular bacteria, and self-DNA in autoimmunity [30]. cGAS binds DNA and synthesizes the second messenger 2'3'-cGAMP, which activates the endoplasmic reticulum-resident adaptor STING. Activated STING then traffics to the Golgi, recruiting TBK1 and IRF3 to induce type I IFNs [29] [30].

- Regulation of cGAS: Multiple E3 ligases and DUBs control cGAS stability and activity. TRIM56 induces monoubiquitination of cGAS at Lys335, enhancing its dimerization, DNA-binding capacity, and cGAMP production [30]. RNF185 mediates K27-linked polyubiquitination of cGAS to enhance its enzymatic activity [30]. To prevent excessive activation, the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) also targets nuclear cGAS for degradation, a process mediated by the CRL5-SPSB3 E3 complex [30]. The deubiquitinase USP14 counteracts ubiquitination to stabilize cGAS by recruiting TRIM14 under IFN-I stimulation [30].

- Regulation of STING: STING activation and turnover are critically controlled by ubiquitination. Positive regulators include TRIM56, TRIM32, and RNF115, which promote K63-linked polyubiquitination of STING, facilitating its dimerization, Golgi translocation, and recruitment of TBK1 [30]. The ER-resident E3 complex AMFR/INSIG1 catalyzes K27-linked polyubiquitination of STING, which is also required for TBK1 recruitment and IFN production [30]. Negative regulation is achieved through K48-linked ubiquitination. RNF5 and TRIM30α promote K48-linked polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of STING, terminating the signal [30]. Furthermore, activated STING is eventually targeted for lysosomal degradation via a microautophagy mechanism that requires K63-linked ubiquitination at Lys288, a process involving the ESCRT complex [30].

Table 3: Key Ubiquitin-Related Enzymes in the cGAS-STING Pathway

| Enzyme Name | Type | Target Protein | Ubiquitin Linkage | Function in Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIM56 | RING E3 Ligase | cGAS, STING | Monoubiquitin, K63 | Enhances cGAS activity & STING trafficking [30]. |

| RNF185 | RING E3 Ligase | cGAS | K27 | Enhances cGAS enzymatic activity [30]. |

| AMFR/INSIG1 | RING E3 Complex | STING | K27 | Promotes STING aggregation and TBK1 recruitment [30]. |

| RNF5 | RING E3 Ligase | STING | K48 | Negatively regulates signaling by targeting STING for degradation [30]. |

| USP14 | DUB | cGAS | K48 (removal) | Stabilizes cGAS by cleaving ubiquitin chains [30]. |

Figure 3: Ubiquitin Regulation of the cGAS-STING DNA Sensing Pathway. Activating ubiquitin modifications promote cGAS and STING function, while degradative ubiquitination and lysosomal turnover ensure pathway termination.

Ubiquitination in Inflammasome Activation

Inflammasomes are multiprotein complexes (e.g., NLRP3, AIM2) that assemble in response to infection or cellular stress, leading to the activation of caspase-1 and the maturation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 [25] [32]. Ubiquitination serves as a critical regulatory switch for both the priming and activation steps of inflammasome formation.

- Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome: The NLRP3 sensor is tightly controlled by ubiquitination. In its inactive state, NLRP3 is constitutively modified by K48-linked ubiquitin chains, maintaining low protein levels [25] [32]. During the priming phase (e.g., via TLR signaling), deubiquitination of NLRP3 by DUBs such as BRCC3 is required for its activation and inflammasome assembly [25]. Conversely, E3 ligases like A20 and TRIM31 can negatively regulate NLRP3 by promoting its ubiquitination and degradation [32].

- Regulation of Inflammatory Cell Death (Pyroptosis): Ubiquitination also controls inflammatory cell death pathways like pyroptosis and necroptosis, which are closely linked to inflammasome activity [24] [32]. For instance, in the necroptosis pathway, the kinase RIPK3 and its substrate MLKL are regulated by ubiquitination. E3 ligases such as cIAP1/2 promote K63-linked ubiquitination of RIPK1, which can suppress necroptotic cell death, while DUBs can promote it [32]. In sepsis, the ubiquitin-dependent modification of RIPK1 and NLRP3 is a key factor in controlling the intensity of the inflammatory response [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Studying ubiquitination in innate immunity requires a specialized set of molecular tools and reagents. The following table details key resources for probing these pathways.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitin in Innate Immunity

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Key Function & Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Mutants (K-only, K0, ΔGG) | Molecular Biology | Determine ubiquitin linkage specificity; K0 (all lysines mutated to arginine) blocks polyubiquitination; ΔGG (C-terminal glycine deletion) prevents conjugation and serves as a negative control [26]. | Identify if a protein modification is K63-linked by co-expressing a ubiquitin mutant where only K63 is available [26]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (Bortezomib, MG132) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Inhibit the 26S proteasome, causing accumulation of K48-linked polyubiquitinated proteins; used to test if a protein's degradation is proteasome-dependent [27] [31]. | Stabilize a protein of interest (e.g., STING) to investigate if its turnover is mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system [30] [27]. |

| Specific E3 Ligase & DUB Inhibitors | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Chemically perturb the activity of specific enzymes to assess their function in a pathway (e.g., HBX 41,108 for USP7; PR-619 as a broad-spectrum DUB inhibitor) [31]. | Test the role of a specific DUB in regulating RLR signaling by treating cells with an inhibitor and measuring IFN production. |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Genetic Tool | Perform loss-of-function screens to identify novel E3s/DUBs involved in PRR signaling; genome-wide libraries enable unbiased discovery [14]. | Identify regulators of the cGAS-STING pathway by screening an E3 ligase-focused siRNA library for modulators of IFN-β promoter activity. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Immunological Reagent | Detect and quantify specific ubiquitin chain types (e.g., K48-linkage, K63-linkage, linear) in Western blot or immunofluorescence [14]. | Confirm that an immune stimulus induces K63-linked ubiquitination of MAVS by immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot with anti-K63-linkage specific antibody. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Affinity Reagents | Isolate and enrich polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates while protecting them from DUB activity, facilitating proteomic analysis [14]. | Enrich and identify novel ubiquitinated proteins in the TLR4 signaling complex by mass spectrometry after LPS stimulation. |

| Anthrone | Anthrone Reagent|Carbohydrate Assay Chemical|RUO | Anthrone is a high-purity reagent for colorimetric carbohydrate quantification in research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Avenacein Y | Avenacein Y, CAS:93752-78-4, MF:C15H10O8, MW:318.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides standardized methodologies for key experiments used to dissect ubiquitination in immune signaling pathways.

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) to Assess Protein-Protein Interactions and Ubiquitination

Objective: To determine if a protein of interest (POI) interacts with a specific E3 ligase or DUB, or to confirm its ubiquitination status in a physiological context.

Protocol:

- Cell Transfection & Stimulation: Transfect cells (e.g., HEK293T, THP-1) with plasmids expressing your POI, relevant ubiquitin constructs (e.g., HA-Ub, Myc-Ub), and/or the E3/DUB of interest. Alternatively, stimulate innate immune cells (e.g., bone marrow-derived macrophages) with relevant ligands (LPS, Poly(I:C), cGAMP).

- Cell Lysis: Harvest cells and lyse in a non-denaturing IP lysis buffer (e.g., 1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, aprotinin) and 10-20 mM N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit endogenous DUBs.

- Immunoprecipitation: Pre-clear the lysate with Protein A/G beads. Incubate the supernatant with an antibody against your POI or a tag (e.g., anti-FLAG, anti-HA) for 2-4 hours at 4°C. Add Protein A/G beads and incubate for an additional 1-2 hours.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads 3-5 times with lysis buffer. Elute the immunoprecipitated complexes by boiling in 2X Laemmli SDS sample buffer.

- Immunoblotting: Resolve the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane. Probe the membrane with antibodies against ubiquitin, specific ubiquitin linkages, or the interacting E3/DUB to assess interaction or ubiquitination.

2In VitroUbiquitination Assay

Objective: To reconstitute the ubiquitination reaction using purified components and directly test if an E3 ligase can ubiquitinate a candidate substrate.

Protocol:

- Purification of Components: Purify recombinant E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme, E3 ligase, substrate protein, and ubiquitin from E. coli or using an in vitro transcription/translation system.

- Reaction Setup: In a reaction tube, combine the following in ubiquitination assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP):

- E1 enzyme (100 nM)

- E2 enzyme (1-5 µM)

- E3 ligase (0.5-2 µM)

- Substrate protein (2-5 µM)

- Ubiquitin (50-100 µM)

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 1-2 hours.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop the reaction by adding SDS sample buffer and boiling. Analyze the products by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, using an antibody against the substrate or a tag on the substrate to detect upward molecular weight shifts indicative of ubiquitination.

RNAi-based Functional Screen for Ubiquitin Pathway Regulators

Objective: To systematically identify E3 ligases or DUBs that regulate a specific innate immune pathway.

Protocol:

- Reporter Cell Line Generation: Stably transduce a relevant cell line (e.g., HEK293, monocytic cell line) with a reporter construct (e.g., IFN-β promoter driving luciferase or GFP).

- Screen Execution: Reverse-transfect the reporter cells with a genome-wide or focused siRNA/shRNA library targeting E3s and DUBs. Include non-targeting siRNA controls.

- Stimulation and Readout: After 48-72 hours to allow for gene knockdown, stimulate the cells with a pathway-specific agonist (e.g., Sendai virus for RLRs, HT-DNA for cGAS-STING). Measure the reporter activity (luminescence/fluorescence) 6-24 hours post-stimulation.

- Hit Validation: Identify siRNAs that significantly enhance or suppress the reporter response. Validate primary hits using individual siRNAs and measure endogenous mRNA levels of immune genes (e.g., IFNB1, CXCL10) by qRT-PCR. Confirm the physical interaction between the validated hit and pathway components by Co-IP [14].

The tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) signaling pathway represents a paradigm for understanding how cells process extracellular inflammatory signals into decisive fate determinations. This process is governed by an intricate balance between competing ubiquitination and deubiquitination events that ultimately determine whether a cell survives, undergoes apoptosis, or proceeds to necroptosis. Ubiquitination, once primarily recognized as a mere tag for protein degradation, has emerged as a sophisticated signaling mechanism that regulates diverse cellular processes including inflammatory response, immune activation, and cell death. Within the context of a broader thesis on ubiquitination in DNA repair and immune response pathways, the TNF-α system offers a compelling model of how reversible post-translational modifications coordinate complex biological outcomes through dynamic protein regulation.

The ubiquitin system employs a cascade of enzymatic reactions involving E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases that collectively conjugate ubiquitin to target proteins [33]. This process is reversible through the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin modifications, providing a sophisticated regulatory switch for signaling pathways [34]. The complexity of ubiquitin signaling is magnified by the ability to form different polyubiquitin chain linkages—including K48-linked, K63-linked, and linear chains—each encoding distinct functional outcomes for the modified protein [33]. In TNF-α signaling, this ubiquitin code determines the assembly and disassembly of signaling complexes that dictate cellular fate, making it a quintessential model for understanding how competing ubiquitination and deubiquitination events govern fundamental biological processes.

Molecular Players in the TNF-α Signaling Pathway

Core Signaling Complexes

The TNF-α signaling cascade initiates when the cytokine binds to its cognate receptor TNFR1, leading to the assembly of a primary signaling complex known as Complex I [35]. This membrane-associated complex serves as the platform for the initial ubiquitination events that determine subsequent signaling trajectories. The core components of Complex I include:

- TRADD (TNFRSF1A-associated via death domain): Functions as a scaffold protein that recruits other signaling molecules to the activated receptor [35].

- RIPK1 (Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1): Serves as a critical signaling hub whose ubiquitination status dictates pathway orientation [33].

- TRAF2 (TNF receptor-associated factor 2): Recruits cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (c-IAPs) to the complex [35].

- c-IAP1/2 (Cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins 1 and 2): E3 ubiquitin ligases that mediate ubiquitination of RIPK1 and other complex components [33].

Following Complex I formation, a series of orchestrated ubiquitination events determine whether the cell will proceed toward NF-κB-mediated survival or initiate cell death pathways. The ubiquitination status of RIPK1 represents a critical decision point, with different ubiquitin linkages producing diametrically opposed cellular outcomes.

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases and Their Functions

E3 ubiquitin ligases confer substrate specificity to the ubiquitination system and play decisive roles in TNF-α signaling. The key E3 ligases involved include:

- c-IAP1/2: These RING domain-containing E3 ligases mediate K63-linked ubiquitination of RIPK1, particularly on lysine 377 in humans, which is critical for NF-κB activation [33]. They also promote K48-linked ubiquitination of RIPK1 under certain conditions, leading to its proteasomal degradation and inhibition of cell death [33].

- LUBAC (Linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex): Composed of HOIP, HOIL-1, and SHARPIN, this multi-subunit E3 complex generates linear ubiquitin chains on components including NEMO, RIP1, and TNFR1 itself [33]. LUBAC stabilizes signaling complexes and facilitates MAPK and NF-κB activation [33]. Genetic studies demonstrate that HOIP deficiency induces embryonic lethality that can be rescued by TNFR1 deletion, underscoring LUBAC's critical role in TNF signaling [33].

Table 1: Key E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in TNF-α Signaling

| E3 Ligase | Components | Ubiquitin Linkage | Key Substrates | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-IAP1/2 | Single subunit RING ligases | K63, K48, K11 | RIPK1, themselves | Promotes NF-κB activation; regulates cell death |

| LUBAC | HOIP, HOIL-1, SHARPIN | Linear | NEMO, RIPK1, TNFR1 | Stabilizes signaling complexes; enhances NF-κB signaling |

| TRAF2 | Single subunit RING ligase | K63 | RIPK1 | Recruits c-IAP1/2; initiates ubiquitination cascade |

Deubiquitinating Enzymes and Their Regulatory Roles

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) provide counter-regulatory functions that terminate or modulate ubiquitin-dependent signaling. The major DUBs operating in the TNF-α pathway include:

- CYLD (Cylindromatosis): A tumor suppressor DUB that removes K63-linked ubiquitin chains from RIPK1, thereby attenuating NF-κB activation and promoting cell death [36] [37]. CYLD-mediated deubiquitination of RIPK1 facilitates the transition from Complex I to death-inducing complexes [36].

- A20 (TNFAIP3): This DUB exhibits dual functionality, removing K63-linked ubiquitin chains from RIPK1 while subsequently promoting its K48-linked ubiquitination, thereby terminating NF-κB signaling and promoting RIPK1 degradation [35]. This sequential activity represents a process called "ubiquitin editing" that ensures signal termination [38].

- OTUD7B: Recruited to activated TNFR1 where it promotes RIPK1 deubiquitination, attenuating NF-κB activation [35].

- USP21: Inhibits TNF-α-induced NF-κB signaling by promoting deubiquitination of RIPK1 [39].

- USP4: Targets TRAF2 and TRAF6 for deubiquitination and inhibits TNFα-induced cancer cell migration [40].

Table 2: Major Deubiquitinating Enzymes in TNF-α Signaling

| DUB | Family | Key Substrates | Ubiquitin Linkage Specificity | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYLD | USP | RIPK1, TRAF2, TRAF6 | K63 | Attenuates NF-κB; promotes cell death |

| A20 (TNFAIP3) | OTU | RIPK1, TRAF6 | K63 (removal), K48 (addition) | Terminates NF-κB via "ubiquitin editing" |

| USP21 | USP | RIPK1 | K63 | Inhibits NF-κB activation |

| USP4 | USP | TRAF2, TRAF6 | K63 | Negatively regulates TNFα-induced signaling |

| OTUD7B | OTU | RIPK1 | K63 | Attenuates NF-κB activation |

The Ubiquitin-Driven Fate Decision Mechanism

NF-κB Activation Pathway

When pro-survival signaling predominates, the ubiquitination events in Complex I create a platform for IKK (IκB kinase) and TAK1 (TGF-β-activated kinase 1) complex activation, leading to NF-κB-mediated gene transcription. This process involves:

- K63-linked and linear ubiquitin chains on RIPK1, generated by c-IAP1/2 and LUBAC, serve as scaffolding platforms [33].

- TAK1 complex (TAK1-TAB2-TAB3) is recruited through binding of TAB2/3 to K63-linked ubiquitin chains via their C-terminal zinc finger domains [33].

- The IKK complex (IKKα-IKKβ-NEMO) is recruited through binding of NEMO to both K63-linked and linear ubiquitin chains via its UBAN (ubiquitin binding in ABIN and NEMO proteins) domain [33].

- TAK1 phosphorylates and activates IKKβ, which then phosphorylates IκBα, targeting it for K48-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [37].

- This releases the NF-κB dimer (typically p50-RelA) to translocate to the nucleus and activate transcription of anti-apoptotic and inflammatory genes [35].

The resulting gene expression promotes cell survival through upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins (BIRC2, BIRC3, BCL2L1) and inflammatory mediators (IL-6), rendering the cell resistant to death signals [35].

Cell Death Pathway Activation

When deubiquitination events prevail, particularly through the actions of CYLD and A20, RIPK1 undergoes deubiquitination and dissociates from Complex I, leading to the formation of cytoplasmic death-inducing complexes:

- Complex IIa (also known as the apoptosome) forms when deubiquitinated RIPK1 associates with FADD and caspase-8, initiating extrinsic apoptosis through caspase-8 activation [35].

- Complex IIb (necrosome) forms when RIPK1 associates with RIPK3 and MLKL, initiating necroptosis, a programmed necrotic cell death pathway [33].

- Activation of caspase-8 within these complexes triggers a proteolytic cascade that executes apoptosis, while phosphorylation of MLKL by RIPK3 initiates necroptosis through membrane disruption [35].

The balance between these opposing pathways is precisely regulated by the ubiquitination status of RIPK1, which serves as a molecular switch determining cellular fate.

Figure 1: The TNF-α Fate Decision Paradigm - Competing ubiquitination and deubiquitination of RIPK1 determine whether cells survive via NF-κB signaling or die through apoptosis or necroptosis.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Models and Reagents

Research into TNF-α signaling ubiquitination has employed sophisticated experimental systems ranging from cell culture models to genetically engineered mice. The following research reagents represent essential tools for investigating this pathway:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TNF-α Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Human FLS cells, HeLa, HEK293, Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | Model cellular systems for signaling studies | Pathway manipulation; knockout/knockdown studies |

| Animal Models | ACLT mouse model, TIA mouse model, CYLD-/- mice, HOIP-/- mice | In vivo validation of pathway mechanisms | Osteoarthritis studies, embryonic development, inflammation models |

| Cytokines/Activators | Recombinant TNF-α, IL-1β, TNF-α inducing agents | Pathway stimulation | Signal activation under controlled conditions |

| E3 Ligase Reagents | c-IAP1/2 expression vectors, LUBAC components, TRAF2 plasmids | E3 ligase function manipulation | Overexpression and functional studies |

| DUB Reagents | CYLD plasmids, USP4 siRNA, A20 knockout cells, OTUD7B inhibitors | DUB function manipulation | Deubiquitination mechanism studies |

| Ubiquitin Probes | K63-linked ubiquitin chains, linear ubiquitin chains, ubiquitin binding domain fusions | Ubiquitin chain interaction studies | Binding assays; complex purification |

| Signaling Inhibitors | SMAC mimetics, IAP antagonists, TAK1 inhibitors, IKK inhibitors | Pathway inhibition | Functional dissection of specific components |

Methodological Framework for Investigating Ubiquitination in TNF-α Signaling

The experimental delineation of ubiquitination mechanisms in TNF-α signaling employs a multidisciplinary approach combining biochemical, genetic, and pharmacological techniques:

1. Complex Isolation and Composition Analysis:

- Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): Protein complexes are immunoprecipitated from TNF-α-stimulated cells using antibodies against specific complex components (TNFR1, RIPK1, or TRADD) [39]. The composition of these complexes is then analyzed by Western blotting for associated proteins.

- Tandem Affinity Purification: For higher purity, sequential purification tags allow isolation of native complexes from stimulated cells, followed by mass spectrometric analysis to identify all components.

2. Ubiquitination Status Assessment:

- Denaturing Immunoprecipitation: Cells are lysed in denaturing buffers (containing SDS) to disrupt non-covalent interactions before immunoprecipitation of the protein of interest (e.g., RIPK1). This approach specifically detects covalently attached ubiquitin modifications rather than associated proteins [36].

- Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Determination:

- Linkage-Specific Antibodies: Antibodies specific for K63-linked, K48-linked, or linear ubiquitin chains distinguish chain topology in Western blot analyses [33].

- Ubiquitin Mutants: Expression of ubiquitin mutants (K63R, K48R) identifies chain linkages required for specific signaling outcomes.

3. Functional Manipulation of Ubiquitination Machinery:

- Genetic Approaches:

- RNA Interference: siRNA or shRNA-mediated knockdown of specific E3 ligases (c-IAP1/2, LUBAC components) or DUBs (CYLD, A20, USP21) tests their necessity in pathway regulation [40] [39].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout: Complete gene disruption provides definitive evidence of protein function in ubiquitination signaling.

- Pharmacological Approaches:

- Proteasome Inhibitors: MG132 or bortezomib treatment distinguishes between proteasomal degradation-dependent and -independent ubiquitin signaling.

- IAP Antagonists: SMAC mimetics promote c-IAP1/2 degradation, specifically testing their contributions to pathway regulation.

- DUB Inhibitors: Emerging selective DUB inhibitors enable acute pharmacological inhibition of specific deubiquitinating enzymes.

4. In Vivo Validation:

- Animal Disease Models: The ACLT (anterior cruciate ligament transection) and TIA (TNF-α induced arthritis) mouse models evaluate the pathophysiological relevance of ubiquitination mechanisms in inflammatory diseases [36].

- Genetic Mouse Models: Tissue-specific knockout mice conditionally eliminate ubiquitination pathway components in relevant cell types.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Investigating Ubiquitination in TNF-α Signaling - A multidisciplinary approach combining biochemical, genetic, and in vivo methods.

Quantitative Assessment of Ubiquitination Effects

Rigorous quantification of ubiquitination effects on TNF-α signaling outcomes has yielded critical insights into pathway regulation: