Ubiquitin Tagging vs. Antibody Enrichment: A Strategic Guide for Proteomics and Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two pivotal methods for analyzing protein ubiquitination: ubiquitin tagging and antibody-based enrichment.

Ubiquitin Tagging vs. Antibody Enrichment: A Strategic Guide for Proteomics and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two pivotal methods for analyzing protein ubiquitination: ubiquitin tagging and antibody-based enrichment. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles, methodological workflows, and specific applications of each technique. The content delves into troubleshooting common challenges, optimizing protocols for superior results, and offers a direct comparative analysis to guide method selection. By synthesizing current methodologies and emerging trends, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to effectively map ubiquitin signaling in basic research and advance the development of novel therapeutics, such as antibody-drug conjugates.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Code: Why Analysis is Complex and Crucial

The ubiquitin system, once recognized primarily for its role in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, is now understood as a sophisticated post-translational language regulating virtually all cellular processes. This complex signaling system employs diverse ubiquitin chain architectures and conjugation sites to control protein stability, activity, localization, and interactions. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling arises from its ability to form different chain linkages—homotypic, heterotypic, or branched—each capable of encoding distinct functional outcomes. Recent methodological advances have significantly expanded our understanding of non-canonical ubiquitination events, including modifications on non-lysine residues and even non-proteinaceous molecules. This guide objectively compares two fundamental methodological approaches—ubi-tagging and antibody-based enrichment—for studying the ubiquitin system, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their methodological selections.

Methodological Foundations in Ubiquitin Research

Table 1: Core Methodologies for Studying Protein Ubiquitination

| Method Category | Key Principle | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubi-Tagging | Engineered ubiquitin fusion proteins for site-specific conjugation [1] | Generating homogeneous antibody conjugates, bispecific engagers, targeted therapeutics [1] | Rapid reaction time (30 min), high homogeneity, site-specific control [1] |

| Antibody-Based Enrichment | Immunoaffinity capture using ubiquitin-specific antibodies [2] [3] | Proteome-wide ubiquitination profiling, target-specific ubiquitination status [2] [3] | Preservation of endogenous modification, compatibility with clinical samples [3] |

| UBD-Based Approaches | Tandem ubiquitin-binding domains for high-affinity capture [2] [3] | Unbiased enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins, detection of various linkage types [2] [3] | High affinity for polyubiquitin chains, reduced linkage bias compared to antibodies [2] |

Ubi-Tagging: A Modular Conjugation Platform

Ubi-tagging represents a protein engineering approach that exploits the natural ubiquitination machinery for controlled, site-specific conjugation. This methodology addresses the long-standing challenge of product heterogeneity in antibody-drug conjugates and other ubiquitin-fusion proteins.

Experimental Protocol and Performance Data

The standard ubi-tagging protocol involves several key components: (1) a donor ubi-tag (Ubdon) containing a free C-terminal glycine with the conjugating enzyme-specific lysine mutated to arginine to prevent homodimer formation; (2) an acceptor ubi-tag (Ubacc) carrying the corresponding conjugation lysine residue with an unreactive C-terminus; and (3) specific ubiquitination enzymes (E1 and E2-E3 fusion proteins) [1].

In a representative experiment demonstrating the efficiency of this system, researchers conjugated anti-mouse CD3 Fab-Ub(K48R)don with rhodamine-labeled Ubacc-ΔGG using recombinant E1 and the K48-specific E2-E3 fusion protein gp78RING-Ube2g2 [1]. The reaction achieved complete consumption of the starting Fab material within 30 minutes, forming a single fluorescent product with the expected molecular weight [1]. Conversion efficiency quantified across multiple reactions reached 93-96% for ubi-tagged antibodies, demonstrating exceptional reaction completeness [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Ubi-Tagging

| Performance Parameter | Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Time | 30 minutes | Complete consumption of Fab-Ub(K48R)don observed [1] |

| Conversion Efficiency | 93-96% | Average across ubi-tagging reactions with antibodies [1] |

| Thermostability | ~75°C infliction temperature | No alteration compared to unconjugated Fab-Ub(K48R)don [1] |

| Functional Antigen Binding | Comparable to parental antibody | Flow cytometry on CD3+ mouse splenocytes [1] |

| Multimerization Capacity | Up to 11th order multimers | Formation of higher-order ubiquitin chains with Fab-UbWT [1] |

Antibody-Based Enrichment: Capturing Endogenous Ubiquitination

Antibody-based methodologies enable the study of endogenous ubiquitination events without genetic manipulation of the target system. These approaches utilize antibodies that recognize ubiquitin itself or specific ubiquitin chain linkages to isolate and characterize ubiquitinated proteins from complex biological samples.

Technological Evolution and Performance Benchmarks

Recent advances in antibody-based platforms have focused on improving affinity, specificity, and throughput. A notable development is the ThUBD (Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain)-coated 96-well plate technology, which demonstrates significant performance improvements over previous generation TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity)-based platforms [2].

This high-throughput system exhibits a 16-fold wider linear range for capturing polyubiquitinated proteins from complex proteome samples compared to TUBE-coated plates, with detection sensitivity as low as 0.625 μg of sample input [2]. The platform supports flexible analysis of both global ubiquitination profiles and target-specific ubiquitination status, making it particularly valuable for dynamic monitoring of ubiquitination in PROTAC drug development [2].

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitination Detection

The standard protocol for ThUBD-based ubiquitination detection involves: (1) coating high-binding 96-well plates with purified ThUBD protein (optimized at 1.03 μg per well for Corning 3603 plates); (2) blocking plates to prevent non-specific binding; (3) incubating with complex proteome samples; (4) thorough washing with optimized buffer systems; and (5) detection using HRP-conjugated detection reagents with chemiluminescent or colorimetric readouts [2]. This workflow enables specific binding to approximately 5 pmol of polyubiquitin chains under optimal conditions [2].

Comparative Analysis: Ubi-Tagging vs. Antibody-Based Enrichment

Table 3: Direct Method Comparison for Ubiquitin Research Applications

| Comparison Parameter | Ubi-Tagging Approach | Antibody-Based Enrichment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Engineering defined protein conjugates [1] | Analytical detection of endogenous ubiquitination [2] [3] |

| Specificity Control | High (engineered site-specificity) [1] | Variable (depends on antibody quality and linkage specificity) [3] |

| Sample Compatibility | Requires recombinant components [1] | Native tissues and clinical samples [4] [3] |

| Throughput Capacity | Moderate (batch conjugation reactions) [1] | High (96-well plate format) [2] |

| Key Limitation | Not suitable for endogenous profiling [1] | Potential linkage bias and affinity limitations [2] [3] |

| Typical Reaction/Processing Time | 30 minutes [1] | Several hours including incubation and washing steps [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination Enzymes | Catalyze the conjugation of ubiquitin to substrates [1] | E1 activating enzyme, E2 conjugating enzymes (e.g., Ube2g2), E3 ligases (e.g., gp78RING) [1] |

| Linkage-Specific Binders | Enrich or detect specific ubiquitin chain types [2] [3] | ThUBD (unbiased recognition), K48-specific antibodies, K63-specific antibodies [2] [3] |

| Anti-diglycine (K-GG) Antibodies | Enrich tryptic peptides with ubiquitin remnant motif [5] | Immunoaffinity purification of K-GG peptides for mass spectrometry [5] |

| Ubiquitin Variants | Engineered ubiquitin for specific applications [1] | Ub(K48R)don, Ubacc-ΔGG, Strep-tagged Ub, His-tagged Ub [1] [3] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Monitor deubiquitinating enzyme activity | Ubiquitin-based probes with warhead groups (not detailed in results) |

| Platform-Specific Tools | High-throughput ubiquitination analysis [2] | ThUBD-coated 96-well plates, PROTAC assay plates [2] |

Visualization of Ubiquitin Signaling and Methodological Workflows

The Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

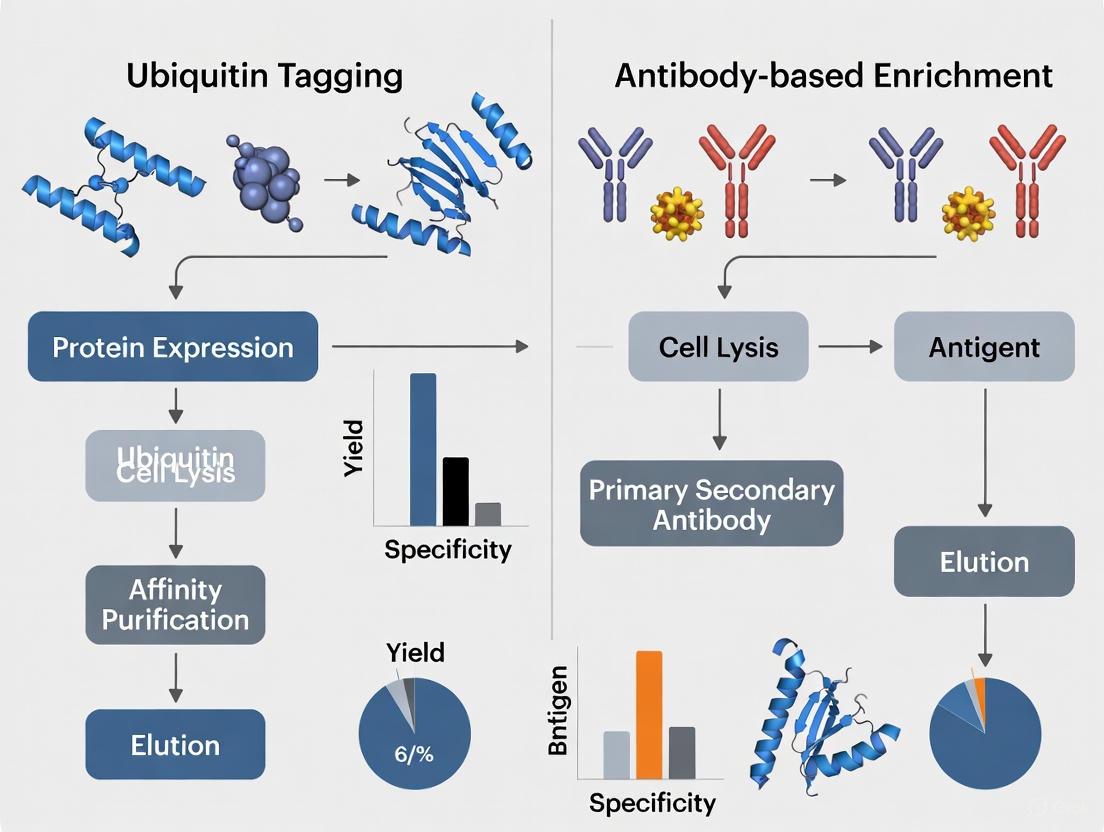

Ubi-Tagging Experimental Workflow

Antibody-Based Enrichment Workflow

The expanding toolkit for ubiquitin research, exemplified by the contrasting strengths of ubi-tagging and antibody-based enrichment methods, reflects the growing appreciation of ubiquitin signaling complexity. Ubi-tagging offers precision engineering of defined conjugates with exceptional homogeneity and efficiency, making it invaluable for therapeutic applications. Conversely, antibody-based platforms provide the sensitivity and throughput needed for analytical profiling of endogenous ubiquitination events in physiological and pathological contexts. The continued refinement of these methodologies—including emerging approaches for studying non-canonical ubiquitination—will undoubtedly uncover additional layers of complexity in the ubiquitin code, further cementing its status as a central regulatory system far beyond a simple degradation signal.

This guide objectively compares the performance of ubiquitin tagging and antibody-based enrichment methods, two principal strategies for ubiquitination analysis. The comparison is framed within the broader research goal of overcoming the inherent analytical challenges of studying ubiquitination: its low natural abundance and the structural complexity of ubiquitin chains.

Methodologies at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core principles and characteristics of each method.

| Feature | Ubiquitin Tagging | Antibody-Based Enrichment |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Genetic fusion of an affinity tag (e.g., His, Strep) to ubiquitin for purification of conjugated substrates [3]. | Immunoaffinity purification using antibodies against ubiquitin or its remnants (e.g., K-ɛ-GG) [3] [6]. |

| Typical Sample Input | Not explicitly stated; requires genetic manipulation of sample. | ~500 μg - 7 mg of peptide digest for mass spectrometry analysis [7]. |

| Key Reagents | Tagged ubiquitin plasmid, affinity resins (Ni-NTA, Strep-Tactin) [3]. | Anti-K-ɛ-GG or anti-ubiquitin antibodies, protein A/G beads [7] [3]. |

| Stoichiometry | Analyzes tagged ubiquitin pool; may not reflect endogenous stoichiometry. | Targets endogenous ubiquitination; better reflects physiological stoichiometry [6]. |

| Chain Architecture | Can be linkage-specific if tagged ubiquitin with lysine mutations is used [3]. | Requires specific antibodies for different linkage types (M1, K48, K63, etc.) [3]. |

Performance Comparison: Key Metrics and Experimental Data

The following table compares the quantitative performance of both methods based on key metrics critical for researchers.

| Performance Metric | Ubiquitin Tagging | Antibody-Based Enrichment | Comparison Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Efficiency/ Yield | Relatively low identification efficiency; co-purification of non-ubiquitinated proteins [3]. | High relative yield; ~85.7% of identified peptides are K-ɛ-GG peptides [7]. | Antibody-based methods offer superior specificity and purity for enriched ubiquitinated peptides. |

| Throughput & Scalability | Low-throughput due to requirement for genetic manipulation; not feasible for tissue samples [3]. | High-throughput protocols like UbiFast enable multiplexed analysis of 10+ samples in ~5 hours [7]. | Antibody-based methods are more adaptable to high-throughput studies, especially with clinical samples. |

| Sensitivity & Dynamic Range | Detection sensitivity is limited by background from non-specifically bound proteins [3]. | Highly sensitive; ThUBD-coated plates detect ubiquitinated proteins from amounts as low as 0.625 μg, a 16-fold improvement over TUBE-based methods [2]. | Advanced antibody/UBD-based platforms offer significantly higher sensitivity for detecting low-abundance ubiquitination. |

| Linkage-Type Flexibility | Flexible; allows for exploration of specific linkages by using ubiquitin mutants (e.g., K48R) [1] [3]. | Flexible but requires a specific antibody for each linkage type of interest [3]. | Ubiquitin tagging offers more inherent flexibility for probing non-canonical chain architectures. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ubi-Tagging for Site-Specific Protein Conjugation

Ubi-tagging repurposes the enzymatic ubiquitination cascade for precise protein engineering rather than analysis. However, it exemplifies the use of ubiquitin tags and linkage specificity [1] [8].

- Step 1: Construct Design. Generate two key protein fusions:

- Donor Ubi-tag (Ubdon): A protein (e.g., an antibody fragment) fused to ubiquitin where a specific lysine (e.g., K48) is mutated to arginine (K48R) to prevent homopolymerization.

- Acceptor Ubi-tag (Ubacc): A cargo molecule (e.g., a fluorescent dye or peptide) fused to ubiquitin that contains the corresponding conjugation lysine (K48) but has an unreactive C-terminus (ΔGG or blocked with a His-tag).

- Step 2: Enzymatic Conjugation. Incubate the Ubdon and Ubacc fusions (e.g., at a 1:5 molar ratio) with recombinant E1 enzyme and a linkage-specific E2-E3 fusion enzyme (e.g., gp78RING-Ube2g2 for K48 linkage) at 37°C.

- Step 3: Reaction Completion and Purification. The conjugation reaction is typically complete within 30 minutes with an efficiency of 93–96%. The homogeneous conjugate (e.g., Rho-Ub2-Fab) is then purified via affinity chromatography (e.g., protein G for antibodies) [1].

Protocol 2: UbiFast for Multiplexed Ubiquitylome Profiling

The UbiFast method is a high-throughput, antibody-based approach for profiling thousands of ubiquitination sites by mass spectrometry [7].

- Step 1: Protein Digestion. Complex protein samples (as little as 500 μg) are digested with trypsin. This cleaves after arginine and lysine residues, generating peptides with a di-glycine (K-ɛ-GG) remnant on formerly ubiquitinated lysines.

- Step 2: On-Bead Immunoaffinity Enrichment. The peptide digest is incubated with anti-K-ɛ-GG antibody beads. The K-ɛ-GG peptides are specifically bound, while non-modified peptides are washed away.

- Step 3: On-Antibody Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Labeling. While the K-ɛ-GG peptides are still bound to the antibody, they are labeled with TMT reagents. Critically, the di-glycyl remnant is protected and does not get labeled, ensuring specificity.

- Step 4: Elution, Pooling, and Analysis. Peptides are eluted from the antibody, and samples from multiple conditions (up to 10 in a TMT10plex) are combined. The pooled sample is then analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) in approximately 5 hours, enabling the quantification of ~10,000 ubiquitylation sites [7].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents required for implementing these ubiquitination analysis methods.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Ubi-Tag | Genetic construct (e.g., Ub-K48R) for controlled multivalent conjugation [1]. | Generating homogeneous bispecific antibody conjugates for therapeutic development [1] [8]. |

| Recombinant Ubiquitination Enzymes (E1, E2-E3) | Catalyzes the formation of a specific isopeptide bond between ubi-tags [1]. | Executing the ubi-tagging conjugation reaction with high efficiency and linkage control [1]. |

| Anti-K-ɛ-GG Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of endogenous ubiquitination sites from digested samples for MS [7] [3]. | High-throughput ubiquitylome profiling in cell lines and primary tissue samples (UbiFast protocol) [7]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Immunoblotting or enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins with a specific chain topology [3]. | Detecting K48-linked polyubiquitination of tau protein in Alzheimer's disease research [3]. |

| Tandem Hybrid UBD (ThUBD) | High-affinity, linkage-unbiased capture domain for ubiquitinated proteins [2]. | Sensitive, high-throughput detection of global ubiquitination signals in a 96-well plate format [2]. |

| Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Reagents | Isobaric chemical labels for multiplexed quantitative mass spectrometry [7]. | Comparing ubiquitylation sites across 10 different experimental conditions simultaneously [7]. |

Protein ubiquitination is one of the most prevalent post-translational modifications (PTMs) within eukaryotic cells, exerting critical regulatory control over nearly every cellular, physiological, and pathophysiological process [9]. This versatility stems from the complexity of ubiquitin conjugates, which can range from a single ubiquitin monomer (monoubiquitination) to polymers of various lengths and linkage types [10]. The covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, to substrate proteins is mediated by an enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligating enzymes [10]. Conversely, deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) remove ubiquitin, maintaining dynamic homeostasis [11].

A pivotal breakthrough in detecting this modification came from the discovery that tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins generates peptides containing a characteristic Lys-ϵ-Gly-Gly (diGLY) remnant on modified lysine residues [9] [5]. This diGLY signature serves as a "molecular fingerprint" for prior ubiquitination. However, its low abundance relative to unmodified peptides necessitates highly specific enrichment strategies prior to mass spectrometry analysis [9]. This guide objectively compares the two dominant methodological philosophies for diGLY enrichment: antibody-based immunoaffinity and antibody-free chemical tagging approaches, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to inform their methodological choices.

Methodological Principles: Core Enrichment Technologies

Antibody-Based Immunoaffinity Enrichment

The most widely used method for ubiquitinome profiling employs antibodies specifically raised against the diGLY remnant motif [9] [12] [13]. In this workflow, proteins are digested into peptides, and anti-K-ε-GG antibodies are used to immunoaffinity purify diGLY-modified peptides from the complex mixture [5]. A significant advantage of this approach is its direct applicability to any eukaryotic organism or tissue without genetic manipulation [9] [10]. However, a key limitation is that the antibody cannot distinguish the diGLY remnant originating from ubiquitin from those generated by the ubiquitin-like modifiers NEDD8 and ISG15, though studies suggest ~95% of enriched diGLY peptides derive from ubiquitination [9]. Antibodies can also exhibit sequence recognition bias, potentially skewing the representation of certain diGLY peptides [11].

Antibody-Free Chemical Tagging Approaches

To overcome the limitations of antibody-based methods, researchers have developed innovative antibody-free strategies. One such method, the Antibody-Free approach for Ubiquitination Profiling (AFUP), employs a selective chemical tagging strategy [11]. This multi-step process involves:

- Blocking all free amine groups on proteins.

- Hydrolyzing ubiquitin from ubiquitinated proteins using deubiquitinases (USP2 and USP21), which regenerates the free ε-amine group specifically at the former ubiquitination sites.

- Labeling these newly exposed ε-amines with a cleavable biotin tag (NHS-SS-Biotin).

- Enriching the tagged peptides using streptavidin beads [11].

This method eliminates antibody bias and cost concerns, though it requires careful optimization of the blocking and enzymatic steps to ensure specificity [11].

Table 1: Core Principle Comparison of diGLY Enrichment Methods

| Feature | Antibody-Based Immunoaffinity | Antibody-Free Chemical Tagging (AFUP) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Immunoaffinity purification using anti-K-ε-GG antibodies [9] [5] | Chemical labeling of deubiquitinated lysines followed by streptavidin enrichment [11] |

| Key Reagent | Anti-K-ε-GG antibody [9] | Deubiquitinases (USP2/21) & NHS-SS-Biotin [11] |

| Specificity | Also enriches NEDD8/ISG15 diGLY motifs (~5% of identifications) [9] | Specific for sites deconjugated by the DUBs used; independent of diGLY motif |

| Primary Advantage | Direct application to endogenous samples and tissues; well-established [9] [10] | Avoids antibody sequence bias and high cost [11] |

| Primary Disadvantage | Potential for antibody sequence recognition bias [11] | Multi-step protocol requiring optimized reaction conditions [11] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows for these two core methodologies.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data

The ultimate value of an enrichment method is reflected in its performance. The tables below summarize key quantitative metrics from published studies using various methodologies.

Identification Depth and Reproducibility

Table 2: Identification Depth and Reproducibility Across Methods

| Method | Sample Type | Input Amount | Sites Identified | Reproducibility (CV) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated UbiFast (magnetic beads) | Jurkat cells | 500 μg per sample (10-plex) | ~20,000 sites | Significantly improved vs. manual | [14] |

| AFUP (single run) | HeLa cells | 0.8 mg | 349 ± 7 sites | Excellent (CV = 2%) | [11] |

| AFUP + pre-fractionation | 293T cells | Not specified | ~4,000 sites | High (Pearson r ≥ 0.91) | [11] |

| Optimized diGLY-IP (DIA) | MG132-treated HEK293 cells | 1 mg | 35,111 ± 682 sites | 45% of peptides with CV < 20% | [12] |

| Optimized diGLY-IP (DDA) | MG132-treated HEK293 cells | 1 mg | ~20,000 sites | 15% of peptides with CV < 20% | [12] |

Technical and Practical Considerations

Table 3: Technical and Practical Method Comparison

| Characteristic | Antibody-Based | Antibody-Free (AFUP) |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplexing Capability | High (e.g., Automated UbiFast with TMT) [14] | Not demonstrated in cited literature |

| Quantitative Accuracy | High (DIA provides superior accuracy vs. DDA) [12] | High quantitative stability reported [11] |

| Sample Throughput | High, especially with automation (96 samples/day) [14] | Likely lower due to multi-step protocol |

| Novel Site Discovery | Identifies well-known and novel sites [12] | ~40% of identified sites were novel [11] |

| Required Instrumentation | Standard LC-MS/MS; magnetic bead processor for automation [14] | Standard LC-MS/MS |

Experimental Protocols: Key Workflows

Detailed Protocol: Antibody-Based diGLY Enrichment with SILAC

This is a foundational protocol for quantitative ubiquitinome analysis using Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino acids in Cell culture (SILAC) [9].

Cell Culture and Lysis:

- SILAC Media: Culture cells in DMEM lacking lysine and arginine, supplemented with dialyzed FBS and either "light" (L-lysine-2HCl, L-arginine-HCl) or "heavy" (13C6,15N2 L-lysine-2HCl, 13C6,15N4 L-arginine-HCl) isotopes for at least six doublings [9].

- Lysis Buffer: Use a denaturing buffer: 8 M Urea, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). Immediately before use, add protease inhibitors (e.g., Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail) and 5 mM N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes [9].

Protein Digestion and Peptide Cleanup:

- Reduction and Alkylation: Reduce proteins with 5 mM dithiothreitol (45 min, room temperature) and alkylate with 10 mM iodoacetamide (30 min, room temperature in the dark) [14].

- Two-Step Digestion: First, digest with LysC (enzyme-to-substrate ratio 1:50) for 2 hours at room temperature. Then, dilute the urea concentration to ~2 M and digest with trypsin (enzyme-to-substrate ratio 1:50) overnight at room temperature [9] [14].

- Desalting: Acidify peptides with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to a final concentration of 0.5-1%. Desalt using a C18 solid-phase extraction cartridge (e.g., Sep-Pak). Condition the cartridge with acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA, load peptides, wash with 0.1% TFA, and elute with 50% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid. Lyophilize the eluate [9] [15].

diGLY Peptide Immunoaffinity Enrichment:

- Antibody Beads: Use an anti-K-ε-GG antibody conjugated to agarose or magnetic beads. For magnetic beads (HS mag anti-K-ε-GG), one batch is typically sufficient for 1-2 mg of peptide input [14].

- Incubation: Reconstitute peptides in IAP buffer (50 mM MOPS/NaOH pH 7.2, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 50 mM NaCl) and incubate with the antibody beads for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation [15].

- Washing: Wash beads 3-4 times with IAP buffer and twice with HPLC-grade water to remove non-specifically bound peptides [15].

- Elution: Elute diGLY peptides from the beads twice using 0.15% TFA. Combine the eluates and desalt using C18 StageTips or similar micro-columns prior to LC-MS/MS analysis [15].

Detailed Protocol: Antibody-Free AFUP Strategy

This protocol outlines the key steps for the Antibody-Free approach for Ubiquitination Profiling (AFUP) [11].

Amine Blocking and Deubiquitination:

- Blocking: Block all free amine groups (lysine ε-amines and protein N-terminal α-amines) by incubating the protein sample with 0.5% formaldehyde. This critical step prevents off-target labeling later [11].

- Deubiquitination: Add the catalytic core domains of deubiquitinases USP2 and USP21 to the blocked protein sample. Incubate to hydrolyze ubiquitin chains from the substrate proteins, which regenerates a free ε-amine group specifically at the ubiquitination sites [11].

Chemical Labeling and Enrichment:

- Biotinylation: Label the newly exposed ε-amines by adding NHS-SS-Biotin reagent. This reagent reacts specifically with the primary amines that were unmasked by deubiquitination [11].

- Streptavidin Enrichment: Digest the labeled proteins with trypsin. Incubate the resulting peptides with Streptavidin Sepharose beads to enrich for biotinylated peptides, which correspond to the former ubiquitination sites [11].

- Elution: Elute the enriched peptides by cleaving the disulfide bond in the NHS-SS-Biotin linker using dithiothreitol (DTT). The eluted peptides can then be analyzed by LC-MS/MS [11].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful ubiquitinome profiling experiment relies on a suite of specific reagents. The following table details key solutions used in the protocols above.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for diGLY Proteomics

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Key Features / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit [9] | Immunoaffinity enrichment of K-ε-GG peptides. | Contains agarose-conjugated antibody; well-established for manual protocols. |

| HS mag anti-K-ε-GG antibody [14] | Magnetic bead-based enrichment for high-throughput studies. | Enables automation on magnetic particle processors; increases reproducibility. |

| UbiFast Method [14] | Highly multiplexed ubiquitination profiling. | Uses on-antibody TMT labeling for high sensitivity and quantitation from limited input. |

| NHS-SS-Biotin [11] | Chemical tagging of deubiquitinated lysines in AFUP. | Features a cleavable disulfide bond for efficient peptide elution after enrichment. |

| Recombinant USP2/USP21 [11] | Hydrolysis of ubiquitin chains in antibody-free methods. | Non-linkage specific deubiquitinases crucial for generating free ε-amines in AFUP. |

| Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Reagents [14] | Isobaric labeling for multiplexed quantitative proteomics. | Allows pooling of samples; compatible with UbiFast (on-bead labeling). |

The diGLY remnant remains the cornerstone of mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinome profiling. Antibody-based enrichment, particularly when enhanced with automation [14], DIA acquisition [12], and multiplexed quantitation, currently sets the benchmark for depth of coverage, throughput, and quantitative robustness. It is the most suitable approach for large-scale, systems-wide studies. In contrast, antibody-free methods like AFUP [11] provide a powerful complementary strategy, offering a means to overcome antibody bias and potentially access a different subset of the ubiquitinome, including novel sites.

The choice between these methods depends on the specific research question, available resources, and sample type. For the foreseeable future, both approaches will coexist and continue to evolve. The ongoing development of more sensitive mass spectrometers, smarter acquisition modes like DIA, and novel biochemical tools promises to further illuminate the complex landscape of the ubiquitin code, driving discoveries in basic biology and drug development.

Ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) constitute a family of evolutionarily conserved proteins that share structural similarities with ubiquitin and play crucial roles in posttranslational modification of diverse macromolecules [16]. The eukaryotic ubiquitin family encompasses nearly 20 proteins that adopt the characteristic β-grasp fold of ubiquitin yet regulate strikingly diverse cellular processes including nuclear transport, proteolysis, translation, autophagy, and antiviral pathways [16]. As research continues to identify novel UBL substrates that expand our understanding of their functional diversity, the technical challenges in studying these modifications have become increasingly apparent. A primary bottleneck in the field involves the specific enrichment and identification of UBL-modified substrates, particularly distinguishing between different UBL types and their specific linkage patterns.

The specificity concerns in UBL enrichment stem from several inherent challenges. First, the structural similarity among UBLs complicates the development of highly specific enrichment tools. Second, the stoichiometry of UBL modification is typically low under physiological conditions, necessitating highly sensitive enrichment methods. Third, UBLs can form complex chains with different linkage types that dictate functional outcomes, requiring tools that can distinguish these specific architectures. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of two primary technical approaches—ubiquitin tagging and antibody-based enrichment—for studying UBL modifications, providing researchers with experimental data and methodological insights to inform their experimental design.

Methodological Principles and Technical Specifications

Ubiquitin Tagging Approaches

Ubiquitin tagging methodologies involve the genetic engineering of affinity tags onto UBLs, enabling selective purification of modified substrates. This approach typically utilizes epitope tags (Flag, HA, V5, Myc, Strep, His) or protein/domain tags (GST, MBP, SUMO, Halo) fused to the UBL of interest [10]. After cellular expression of the tagged UBL, ubiquitinated substrates are covalently labeled and can be enriched using commercially available resins such as Ni-NTA for His tags or Strep-Tactin for Strep tags [10]. The pioneering work employing 6× His-tagged Ub in yeast identified 110 ubiquitination sites on 72 proteins, demonstrating the utility of this approach for proteomic profiling [10]. More recent innovations include the Stable tagged Ub exchange (StUbEx) cellular system, which replaces endogenous Ub with His-tagged Ub and has identified 277 unique ubiquitination sites on 189 proteins in HeLa cells [10].

A significant advancement in UBL tagging is the recently described "ubi-tagging" technique that exploits the ubiquitination enzymatic cascade for site-directed protein conjugation [1]. This modular approach utilizes ubiquitin fusions with antibodies, antibody fragments, nanobodies, peptides, or small molecules that can be conjugated to target proteins within 30 minutes with remarkable efficiency (93-96% conversion) [1]. The system employs donor ubi-tags (Ubdon) with free C-terminal glycine and mutated conjugating lysine residues to prevent homodimer formation, alongside acceptor ubi-tags (Ubacc) containing the corresponding conjugation lysine but with an unreactive C terminus [1]. This technology demonstrates that large cargo such as 50 kDa Fab' fragments does not hamper ubi-tagging efficiency, enabling generation of defined multimers including bispecific T-cell engagers [1].

Antibody-Based Enrichment Strategies

Antibody-based enrichment utilizes immunoreagents specifically developed to recognize UBLs or their modification signatures. These include pan-specific anti-ubiquitin antibodies (P4D1, FK1/FK2) that recognize all ubiquitin linkages, as well as linkage-specific antibodies targeting particular chain architectures (M1-, K11-, K27-, K48-, K63-linkage specific antibodies) [10]. For UBLs such as SUMO, specific antibodies have been crucial for enrichment despite challenges in identifying modification sites without mutagenesis [17] [18].

A prominent example of antibody-based innovation is the UbiFast method, which employs anti-K-ε-GG antibodies for sensitive ubiquitylation site detection [19]. The recent automation of UbiFast using magnetic bead-conjugated K-ε-GG antibodies (mK-ε-GG) and magnetic particle processing has significantly enhanced reproducibility and throughput, enabling processing of up to 96 samples in a single day [19]. This automated workflow identifies approximately 20,000 ubiquitylation sites from TMT10-plex experiments with 500 μg input per sample processed in approximately 2 hours, representing a substantial improvement over manual methods [19]. The sensitivity of this approach has been demonstrated in profiling patient-derived xenograft tissue samples, highlighting its applicability to clinically relevant material [19].

For UBLs beyond ubiquitin, specialized tools have emerged such as activity-based probes (ABPs) for interferon-inducible Ubl protease USP18, which incorporates unnatural amino acids into the C-terminal tail of ISG15 to enable selective detection of USP18 activity over other ISG15 cross-reactive deubiquitinases [20]. These probes utilize a chemical biology approach with a ubiquitin-like protein recognition element, an electrophilic warhead, and a reporter tag to covalently label active site cysteines, reporting deISGylase activity in complex biological systems [20].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of UBL Enrichment Methods

| Parameter | Ubiquitin Tagging | Antibody-Based Enrichment |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity Control | Genetic manipulation of UBL sequence | Antibody cross-reactivity profile |

| Throughput | Lower (requires genetic modification) | Higher (direct application to samples) |

| Identification Sensitivity | 110-750 ubiquitination sites [10] | ~20,000 ubiquitylation sites with automated UbiFast [19] |

| Linkage Specificity | Limited without additional manipulation | Excellent with linkage-specific antibodies |

| Physiological Relevance | Potential artifacts from tagged UBL expression [10] | Preserves endogenous modification states |

| Application to Tissue Samples | Infeasible for patient/animal tissues without genetic modification [10] | Direct application to clinical specimens [19] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited by genetic manipulability | High with automated platforms [19] |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Sensitivity and Specificity Metrics

Direct comparison of ubiquitin tagging versus antibody-based approaches reveals significant differences in sensitivity and specificity. The development of specialized search engines like pLink-UBL has addressed a critical limitation in UBL modification site identification, particularly for SUMOylation sites that conventional mass spectrometry methods struggle to characterize [17] [18]. pLink-UBL demonstrates superior precision, sensitivity, and speed compared to alternative search engines such as MaxQuant, pFind, and pLink, increasing identified SUMOylation sites by 50-300% from the same datasets [17] [18]. This represents a significant advancement as traditional approaches required UBL mutation to facilitate identification, potentially altering biological behavior.

For ubiquitin specifically, antibody-based approaches have shown remarkable sensitivity when optimized. The automated UbiFast method identifies approximately 20,000 ubiquitylation sites from limited input material (500 μg per sample), far exceeding the 753 lysine ubiquitylation sites on 471 proteins identified through Strep-tagged Ub approaches [19] [10]. This substantial difference highlights the enhanced detection capability of modern antibody-based platforms, particularly for lower-abundance modifications.

Specificity challenges persist in both approaches, though they manifest differently. Ubiquitin tagging methods risk introducing artifacts as tagged UBLs may not perfectly mimic endogenous UBL structure and function [10]. Additionally, histidine-rich and endogenously biotinylated proteins can co-purify with Ni-NTA agarose and Strep-Tactin resins respectively, reducing identification specificity [10]. Antibody-based methods face challenges of cross-reactivity, particularly problematic when studying specific UBL types or linkage architectures. The development of linkage-specific antibodies and TUBEs (tandem ubiquitin binding entities) has significantly addressed these concerns, enabling precise capture of specific polyubiquitination events [21] [10].

Throughput and Reproducibility

Throughput and reproducibility are critical considerations for large-scale proteomic studies and screening applications. Automated antibody-based methods demonstrate significant advantages in these areas, with robotic processing enabling substantially improved reproducibility compared to manual methods [19]. The automation of UbiFast reduced variability across process replicates while dramatically increasing processing throughput to 96 samples in a single day [19]. This level of throughput is particularly valuable for pharmaceutical applications including drug development and profiling, where consistent processing of many samples is essential.

Ubiquitin tagging approaches inherently involve more complex workstreams requiring genetic modification prior to enrichment, limiting their applicability to screen large sample numbers or clinical specimens. However, for focused mechanistic studies in genetically tractable systems, tagging approaches provide valuable specificity controls through genetic manipulation of modification sites.

Table 2: Workflow Characteristics and Applications

| Characteristic | Ubiquitin Tagging | Antibody-Based Enrichment |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Compatibility | Genetically modified systems only | Native biological samples, clinical specimens [19] [10] |

| Processing Time | Days (including genetic manipulation) | ~2 hours for 10 samples, 96 samples in one day (automated) [19] |

| Quantification Capability | Moderate | Excellent with isobaric labeling (TMT) [19] |

| Specialized Equipment Needs | Standard molecular biology equipment | Magnetic particle processor (for automated workflows) [19] |

| Data Analysis Requirements | Standard proteomic workflows | Specialized search engines (pLink-UBL) for certain UBLs [17] [18] |

| Best Applications | Mechanistic studies, validation experiments | Large-scale profiling, clinical samples, drug screening [19] [21] |

Advanced Applications and Specialized Tools

Linkage-Specific Analysis Tools

The functional diversity of UBL signaling is largely encoded in the specific linkage types of polymer chains. Different ubiquitin linkages regulate distinct cellular processes, with K48-linked chains primarily targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation while K63-linked chains regulate signal transduction and protein trafficking [21]. To address the challenge of linkage-specific analysis, tandem ubiquitin binding entities (TUBEs) have been developed with nanomolar affinities for specific polyubiquitin chains [21]. These specialized tools enable investigation of ubiquitination dynamics in specific contexts, such as monitoring K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2 in inflammatory signaling versus K48 ubiquitination induced by PROTACs targeted for degradation [21]. The application of chain-specific TUBEs in high-throughput screening assays provides a platform for quantifying context-dependent linkage-specific ubiquitination of endogenous proteins, advancing both basic research and drug development efforts [21].

Chemical Biology Tools for UBL Proteases

Beyond enrichment of modified substrates, understanding UBL regulation requires tools to study the enzymes that process these modifications, particularly deubiquitinases (DUBs). Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) using ABPs has emerged as a powerful platform for mapping reactive proteins and evaluating functional states of enzymes in complex biological systems [20]. For the interferon-inducible Ubl protease USP18, specifically designed ABPs incorporate unnatural amino acids into the C-terminal tail of ISG15 to enable selective detection of USP18 activity over other ISG15 cross-reactive DUBs [20]. These tools employ a hybrid combinatorial substrate library (HyCoSuL) screening approach to identify mutations in the LRGG tail of ISG15 that enhance selective binding to USP18, demonstrating how chemical biology approaches are addressing specificity challenges in the UBL field [20].

Unexpected Substrate Discovery

Advanced enrichment methodologies have enabled the discovery of unexpected UBL substrates, expanding our understanding of UBL biology. Recently, researchers developed a method combining antibody enrichment of UBL C-terminal peptides with LC-MS/MS analysis and pFind 3 blind search to identify nonprotein substrates [17] [18]. This approach revealed spermidine as a major small-molecule substrate for fission yeast SUMO Pmt3 and mammalian SUMO proteins [17] [18]. Spermidine conjugates to the C-terminal carboxylate group of Pmt3 through its N1 or N8 amino group in the presence of SUMO E1, E2, and ATP, without requiring E3 enzymes, and can be reversed by SUMO isopeptidase Ulp1 [17] [18]. This surprising finding that spermidine may be a common small molecule substrate of SUMO and possibly ubiquitin across eukaryotic species underscores the importance of continued methodological development in UBL enrichment, as novel tools may reveal unexpected aspects of UBL biology [17] [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table provides key research reagents essential for implementing UBL enrichment methodologies, based on tools featured in the cited research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UBL Enrichment Studies

| Reagent | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| pLink-UBL Software | Specialized search engine for UBL modification site identification | Identifies SUMOylation sites without UBL mutation; increases sites identified by 50-300% [17] [18] |

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody | Enriches ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry | Automated UbiFast platform; enables identification of ~20,000 ubiquitylation sites [19] |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitin chains with linkage specificity | Differentiates K48 vs K63 ubiquitination in cellular signaling and PROTAC mechanisms [21] |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) | Chemical tools to monitor enzyme activity in complex systems | Profiles USP18 deISGylating activity in lung cancer cell lines [20] |

| Ubi-Tagging System Components | Modular system for site-directed protein conjugation | Generates bispecific T-cell engagers, nanobody-peptide conjugates (93-96% efficiency) [1] |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | Immunoenrichment of specific ubiquitin chain architectures | Characterizes chain-type specific functions in disease models [10] |

Methodological Protocols

Automated UbiFast Protocol

The automated UbiFast protocol represents a state-of-the-art approach for high-throughput ubiquitylation site identification [19]. This method utilizes magnetic bead-conjugated K-ε-GG antibody (mK-ε-GG) and a magnetic particle processor to achieve highly reproducible enrichment with significantly reduced processing time compared to manual methods. Begin with protein extraction and digestion following standard proteomic protocols. For each sample, utilize 500 μg of peptide material as input. Resuspend peptides in immunoaffinity enrichment buffer and incubate with mK-ε-GG beads for 2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation. Using the magnetic particle processor, wash beads thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound peptides. While still on-bead, label peptides with isobaric tandem mass tag (TMT) reagents for sample multiplexing. Elute bound peptides and pool samples for simultaneous LC-MS/MS analysis. Analyze resulting spectra using appropriate database search algorithms, achieving identification of approximately 20,000 ubiquitylation sites from a TMT10-plex experiment [19].

Ubi-Tagging Conjugation Protocol

The ubi-tagging protocol enables site-specific protein conjugation using ubiquitin biochemistry [1]. This 30-minute procedure efficiently generates defined conjugates including fluorescently labeled Fab' fragments, Fab' multimers, and Fab'-peptide conjugates. Begin by preparing the ubiquitination enzyme mixture containing 0.25 μM E1 enzyme and 20 μM of the appropriate E2-E3 fusion protein (e.g., gp78RING-Ube2g2 for K48-specific linkages). Combine 10 μM of donor ubi-tagged protein (Ubdon, containing K48R mutation to prevent homodimer formation) with 50 μM of acceptor ubi-tag (Ubacc, with ΔGG C-terminal modification to prevent elongation) in reaction buffer. Add the enzyme mixture to initiate conjugation and incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes. Monitor reaction completion by SDS-PAGE, observing complete consumption of the donor ubi-tagged protein. Purify the conjugate using appropriate affinity chromatography (e.g., protein G for antibody fragments). Validate conjugation efficiency by electrospray ionization time-of-flight (ESI-TOF) mass spectrometry, typically achieving 93-96% conversion efficiency [1].

The comparison of ubiquitin tagging and antibody-based enrichment methods reveals a complex landscape where methodological selection must align with specific research objectives. Ubiquitin tagging approaches offer genetic specificity and are invaluable for mechanistic studies in genetically tractable systems, particularly when combined with recent advances in ubi-tagging conjugation technology [1]. Conversely, antibody-based methods provide superior throughput, sensitivity, and applicability to native biological systems and clinical specimens, especially when implemented in automated platforms like UbiFast [19]. The ongoing development of specialized tools including linkage-specific TUBEs [21], activity-based probes for UBL proteases [20], and advanced search algorithms like pLink-UBL [17] [18] continues to address specificity concerns in UBL enrichment. As these methodologies evolve, they will undoubtedly uncover novel aspects of UBL biology and provide increasingly sophisticated tools for researchers and drug development professionals working in this complex field.

Protein ubiquitylation is a fundamental post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular functions, including protein degradation, signal transduction, and immune response [3]. This process involves the covalent attachment of the 76-amino acid ubiquitin protein to substrate proteins, primarily through isopeptide bonds with lysine residues [3]. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling arises from the complexity of ubiquitin conjugates, which can range from single ubiquitin monomers to polymers with different lengths and linkage types [3]. However, the low stoichiometry of ubiquitylation and the complexity of ubiquitin chains have made comprehensive analysis challenging [3] [22].

To address these challenges, enrichment strategies have evolved significantly, moving from tagged ubiquitin expression systems to sophisticated methods for capturing endogenous ubiquitylation events. This evolution has been driven by the need for more physiologically relevant data and the ability to study ubiquitin signaling in clinical and tissue samples where genetic manipulation is infeasible [3] [22]. The choice between tagged ubiquitin and endogenous capture methods represents a critical decision point for researchers, with each approach offering distinct advantages and limitations that must be carefully considered based on experimental goals and sample availability.

Methodological Foundations: Key Ubiquitin Enrichment Techniques

Tagged Ubiquitin Approaches

Tagged ubiquitin methodologies involve the genetic engineering of cells to express ubiquitin fused to an affinity tag, enabling purification of ubiquitylated substrates. The most commonly used tags include 6×His and Strep-tag II, which allow enrichment using Ni-NTA agarose and Strep-Tactin resins, respectively [3]. In this approach, cells are engineered to express the tagged ubiquitin, which becomes incorporated into the cellular ubiquitination machinery and covalently attached to substrate proteins. Following cell lysis, ubiquitinated proteins are purified using resins that specifically bind the affinity tag, after which they can be identified through mass spectrometric analysis [3].

This method was pioneered by Peng et al. (2003), who first demonstrated the large-scale identification of ubiquitination sites by expressing 6×His-tagged ubiquitin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, identifying 110 ubiquitination sites on 72 proteins [3]. Subsequent developments, such as the Stable tagged Ub exchange (StUbEx) cellular system, further refined this approach by enabling replacement of endogenous ubiquitin with His-tagged ubiquitin in human cell lines, leading to the identification of 277 unique ubiquitination sites on 189 proteins in HeLa cells [3]. Similarly, researchers using Strep-tagged ubiquitin constructs have identified 753 lysine ubiquitylation sites on 471 proteins in U2OS and HEK293T cells [3].

Antibody-Based Endogenous Capture Methods

Antibody-based approaches directly target endogenous ubiquitin modifications without requiring genetic engineering of the sample source. The breakthrough enabling these methods was the development of antibodies that specifically recognize the di-glycyl (K-ε-GG) remnant left on tryptic peptides after proteolytic digestion of ubiquitylated proteins [22] [13]. These antibodies allow immunoaffinity enrichment of endogenously ubiquitylated peptides from complex biological samples [13].

A significant advancement in this category is the UbiFast method, which combines antibody-based enrichment with on-bead isobaric labeling for multiplexed analysis [22] [14]. This innovative approach addresses a major limitation: traditional K-ε-GG antibodies cannot recognize their targets when the N-terminus of the di-glycyl remnant is derivatized with tandem mass tags (TMT) [22]. In the UbiFast workflow, K-ε-GG peptides are enriched with anti-K-ε-GG antibody, then labeled with TMT reagents while still bound to the antibody, which protects the di-glycyl remnant from derivatization [22]. The labeled peptides from multiple samples are then combined, eluted, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS [22]. Automation of UbiFast using magnetic bead-conjugated antibodies has further enhanced throughput, enabling processing of up to 96 samples per day with identification of approximately 20,000 ubiquitylation sites from just 500 μg of input material per sample [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Ubiquitin Enrichment Approaches

| Feature | Tagged Ubiquitin | Antibody-Based Endogenous Capture |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Expression of affinity-tagged ubiquitin (His, Strep) in cells | Immunoaffinity enrichment using anti-K-ε-GG or linkage-specific antibodies |

| Sample Requirements | Genetically engineered cell lines | Cell lines, tissues, primary cells, clinical samples |

| Key Advantage | Relatively low-cost; friendly for screening | Studies endogenous ubiquitination without genetic manipulation |

| Main Limitation | Cannot be used on tissues/clinical samples; potential artifacts | High antibody cost; potential non-specific binding |

| Typical Identified Sites | 110-753 sites (early studies) | >10,000 sites with advanced methods like UbiFast |

Technical Comparison: Performance and Applications

Efficiency and Coverage

The evolution of enrichment strategies has led to remarkable improvements in the depth and breadth of ubiquitinome coverage. Early tagged ubiquitin approaches typically identified hundreds of ubiquitination sites, which was groundbreaking at the time but limited compared to current capabilities [3]. In contrast, modern antibody-based methods like the automated UbiFast platform can identify approximately 20,000 ubiquitylation sites from just 500 μg of input material per sample in a TMT10-plex experiment [14].

Quantitative comparisons demonstrate the superior performance of advanced endogenous capture methods. In direct comparisons of sample processing techniques, the automated UbiFast method using magnetic beads significantly outperformed manual agarose-based immunoprecipitation, with the magnetic bead approach identifying 9,624 ubiquitination sites compared to 6,821 sites with agarose beads from the same input amount [14]. This represents a 41% increase in coverage and highlights how methodological refinements continue to enhance experimental outcomes.

Specificity and Background Interference

Both tagged ubiquitin and antibody-based approaches face challenges with specificity, though the nature of interference differs between methods. Tagged ubiquitin systems, particularly those using His-tags, can co-purify histidine-rich proteins, while Strep-tag systems may isolate endogenously biotinylated proteins [3]. These non-specific interactions can reduce the sensitivity of ubiquitinated substrate identification and increase background noise.

Antibody-based methods suffer from different limitations, including potential cross-reactivity and non-specific binding of non-ubiquitinated peptides to the antibody or solid support [3]. However, the development of more specific antibody clones and improved blocking conditions has substantially enhanced signal-to-noise ratios. The implementation of tandem enrichment strategies, such as the SCASP-PTM method that simultaneously enriches ubiquitinated, phosphorylated, and glycosylated peptides from a single sample, further demonstrates how specificity challenges are being addressed through innovative workflow design [23].

Experimental Workflows and Practical Considerations

The practical implementation of ubiquitin enrichment methods involves significantly different workflows, time investments, and technical requirements. Tagged ubiquitin approaches require substantial upfront work in cell line development and validation but offer relatively straightforward downstream processing [3]. In contrast, antibody-based methods eliminate the need for genetic engineering but require careful optimization of enrichment conditions and more complex sample processing.

Table 2: Practical Implementation Comparison Between Methods

| Parameter | Tagged Ubiquitin | Antibody-Based Endogenous Capture |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation Time | Days to weeks (cell line development) | Hours to days (no genetic manipulation needed) |

| Enrichment Processing Time | Several hours | ~2 hours for automated UbiFast [14] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited to 2-3 samples with SILAC | Up to 18 samples with TMT isobaric tagging [22] |

| Required Input Material | Not systematically reported | 500 μg - 1 mg per sample for deep coverage [22] [14] |

| Instrumentation Needs | Standard LC-MS/MS | LC-MS/MS with FAIMS for improved quantification [22] |

Specialized Applications and Emerging Innovations

Linkage-Specific Analysis

Beyond general ubiquitination profiling, specialized approaches have emerged for studying specific ubiquitin chain linkages. Linkage-specific antibodies have been developed that recognize M1-, K11-, K27-, K48-, and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains, enabling researchers to investigate the biological functions associated with different ubiquitin signaling architectures [3]. For example, Nakayama et al. utilized a K48-linkage specific antibody to demonstrate abnormal accumulation of K48-linked polyubiquitinated tau proteins in Alzheimer's disease [3].

Ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) provide an alternative tool for linkage-specific enrichment. Tandem-repeated UBDs with enhanced affinity for specific chain types have been successfully employed to purify and characterize ubiquitinated proteins with defined chain architectures [3]. These approaches have been particularly valuable for deciphering the complex signaling codes embodied in the ubiquitin code.

Advanced Instrumentation and Computational Tools

The evolution of enrichment strategies has been paralleled by advances in mass spectrometry instrumentation and computational analysis. High-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMS) has been integrated into ubiquitin profiling workflows to improve quantitative accuracy for post-translational modification analysis [22]. Additionally, specialized search engines like pLink-UBL have been developed specifically for ubiquitin-like protein modification site identification, demonstrating superior precision, sensitivity, and speed compared to general-purpose proteomics software [17].

A particularly innovative application of ubiquitin biochemistry is the ubi-tagging platform for antibody conjugation. This technology repurposes the ubiquitination machinery for site-specific protein engineering, enabling efficient generation of homogeneous antibody conjugates within 30 minutes with an impressive efficiency of 93-96% [1] [8]. The platform allows creation of multimeric antibody formats, including bispecific T-cell engagers, demonstrating how fundamental ubiquitination principles can be harnessed for therapeutic applications [1].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Ubiquitin Enrichment

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Enrichment Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Tags | 6×His tag, Strep-tag II | Fused to ubiquitin for purification of ubiquitinated substrates from engineered cells [3] |

| Enrichment Antibodies | Anti-K-ε-GG (di-glycyl remnant) | Immunoaffinity enrichment of endogenously ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry [22] [13] |

| Linkage-Specific Reagents | K48-, K63-, M1-linkage specific antibodies | Selective enrichment of ubiquitin chains with specific linkage types [3] |

| Ubiquitination Enzymes | E1 activating, E2 conjugating, E3 ligating enzymes | In vitro ubiquitination assays; ubi-tagging conjugation platform [1] |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | Ulp1, various DUB inhibitors | Control experiments; validation of ubiquitin-dependent signals [17] |

| Mass Spectrometry Tags | Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) reagents | Multiplexed quantitative analysis of ubiquitination sites across multiple samples [22] [14] |

The evolution from tagged ubiquitin to endogenous capture methods represents significant progress in ubiquitin research, with each approach offering distinct advantages for specific research contexts. Tagged ubiquitin methods remain valuable for hypothesis-driven research in genetically tractable systems where controlled expression enables straightforward validation, while antibody-based endogenous capture approaches provide unparalleled access to physiological ubiquitination events in diverse sample types, including clinical specimens.

Future directions in ubiquitin enrichment will likely focus on increasing sensitivity to work with even smaller sample amounts, enhancing linkage-specific analysis capabilities, and integrating ubiquitin profiling with other post-translational modification analyses in multi-omics frameworks. The continued development of innovative technologies like ubi-tagging for therapeutic applications demonstrates how fundamental research into ubiquitin biochemistry continues to yield unexpected translational opportunities. As these methods mature, researchers will be increasingly equipped to decipher the complex ubiquitin code in health and disease, potentially unlocking new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Diagram 1: Decision framework for selecting appropriate ubiquitin enrichment strategies based on sample type and research objectives.

Methodologies in Action: Protocols and Applications from Basic Research to Therapeutics

Protein ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, regulates diverse cellular processes from protein degradation to signal transduction. For researchers aiming to study the ubiquitinome, two principal methodological pathways have emerged: ubiquitin tagging (affinity tag approach) and antibody-based enrichment. The ubiquitin tagging approach involves genetically engineering cells to express ubiquitin fused to an affinity tag (such as His or Strep), enabling purification of ubiquitinated proteins directly. In contrast, antibody-based methods utilize antibodies that recognize endogenous ubiquitin signatures, such as the diGly remnant left on trypsinized peptides, to enrich ubiquitinated species from wild-type cells. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, focusing on the principles, workflow, and performance data of the ubiquitin affinity tag method to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Principle and Components of Ubiquitin Affinity Tagging

The core principle of the ubiquitin affinity tag approach is the genetic replacement or supplementation of endogenous ubiquitin with a tag-modified version. This allows the entire pool of cellular ubiquitinated proteins to be covalently labeled with an affinity handle, facilitating their subsequent purification under denaturing conditions that preserve unstable modifications and protein-complex interactions [3].

- Tag Integration: The DNA sequence for an affinity tag (e.g., His, Strep, FLAG) is fused to the N-terminus of the ubiquitin gene. This construct is then introduced into cells, where the tagged ubiquitin is expressed and processed by the native enzymatic cascade (E1, E2, E3), resulting in its covalent attachment to substrate proteins [3].

- Key Affinity Tags: The most commonly used tags are the 6× His-tag and the Strep-tag. The His-tag binds to immobilized metal ions (e.g., Ni²⁺) on chromatography resins, while the Strep-tag binds with high affinity to Strep-Tactin resins [3] [24].

- System Establishment: In a refined method known as the Stable Tagged Ubiquitin Exchange (StUbEx) system, endogenous wild-type ubiquitin is replaced with His-tagged ubiquitin, ensuring that all cellular ubiquitination events carry the affinity tag [3].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and fundamental principle of this approach.

Detailed Workflow for Ubiquitin Affinity Tagging

The experimental workflow for the ubiquitin tagging approach involves a series of defined steps from cell culture to mass spectrometry analysis, as outlined below.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Cell Line Engineering and Culture:

- Generate a cell line (e.g., HEK293, U2OS) stably expressing N-terminally tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His-Ub or Strep-Ub). The StUbEx system is highly effective for this purpose [3].

- Culture cells under standard conditions. To stabilize ubiquitinated proteins, especially those targeted for proteasomal degradation, treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor such as MG132 (10-25 µM for 3-4 hours) prior to harvesting [25] [26].

Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction:

Affinity Purification of Ubiquitinated Proteins:

- Incubate the clarified, denatured lysate with the appropriate affinity resin:

- For His-tagged Ub: Use Ni-NTA (Nickel-Nitrilotriacetic Acid) agarose resin. Wash with buffers containing decreasing pH (e.g., to pH 6.3) and imidazole (e.g., 20 mM) to reduce non-specific binding. Elute with buffer containing 250-500 mM imidazole [3] [24].

- For Strep-tagged Ub: Use Strep-Tactin resin. Wash and elute under denaturing conditions with a buffer containing desthiobiotin (e.g., 50 mM) or biotin [3].

- Incubate the clarified, denatured lysate with the appropriate affinity resin:

Protein Digestion and Peptide Preparation:

- The purified pool of ubiquitinated proteins is then prepared for mass spectrometry. This typically involves reduction, alkylation, and tryptic digestion. Trypsin cleaves ubiquitin, leaving a signature diGlycine (K-ε-GG) remnant on the modified lysine residue of the substrate peptide, which results in a mass shift of +114.0429 Da [26] [22].

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

Performance Comparison: Ubiquitin Tagging vs. Antibody-Based Enrichment

The table below summarizes key performance metrics and characteristics of the ubiquitin tagging approach compared to the main alternative, antibody-based diGly remnant enrichment.

| Feature | Ubiquitin Tagging (Affinity Tag) | Antibody-Based (diGly Enrichment) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Purification of tagged ubiquitin-protein conjugates at the protein level [3]. | Immunoaffinity enrichment of tryptic peptides containing the K-ε-GG remnant at the peptide level [12] [26]. |

| Required Genetic Manipulation | Yes (stable expression of tagged Ub) [3]. | No (works with wild-type cells and tissues) [12] [22]. |

| Typical Scale of Identified Sites | ~280-750 sites from initial studies [3]. | >35,000 sites in a single experiment (e.g., using DIA) [12]. |

| Compatibility with Tissues/Patients | Infeasible for animal or patient tissues [3]. | Highly suitable for tissue and clinical samples [22]. |

| Linkage-Type Specificity | Can be engineered using ubiquitin mutants for specific linkages [1]. | Requires separate, specific antibodies for different linkage types [3]. |

| Key Advantage | Directly captures the ubiquitinated protein; can study protein complexes. | Extreme depth and sensitivity; high translational potential for clinical samples. |

| Key Disadvantage | Lower identification efficiency; potential for artifacts from tagged Ub expression [3]. | High cost of antibodies; cannot provide information on protein-level conjugates [3]. |

Table: Objective comparison of the ubiquitin affinity tag approach and the antibody-based diGly enrichment method.

Quantitative data from direct comparisons highlights the difference in sensitivity. One study noted that K-GG peptide immunoaffinity enrichment yielded greater than fourfold higher levels of modified peptides than protein-level affinity purification (AP-MS) approaches [26]. Furthermore, while ubiquitin tagging identified hundreds to low-thousands of sites in foundational studies, modern antibody-based diGly methods with Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry routinely identify over 35,000 distinct diGly sites in a single measurement [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of the ubiquitin affinity tag approach requires the following key reagents:

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Plasmid for Tagged-Ub | Expression vector for His-Ub, Strep-Ub, or other tagged ubiquitin constructs. |

| Proteasome Inhibitor (MG132) | Stabilizes ubiquitinated proteins by blocking their degradation [26]. |

| Denaturing Lysis Buffer | Typically contains 6-8 M Urea or Guanidine•HCl; inactivates DUBs to preserve ubiquitination [3]. |

| Affinity Resin | Ni-NTA Agarose (for His-tag) or Strep-Tactin Resin (for Strep-tag) [3] [24]. |

| Imidazole | Used in wash and elution buffers for His-tag purifications to compete with protein binding [24]. |

| Desthiobiotin | A biotin analog used for gentle and efficient elution of Strep-tagged proteins [3]. |

| Trypsin | Protease used to digest purified proteins, generating diGly-modified peptides for MS analysis [22]. |

The ubiquitin affinity tag approach provides a direct method for isolating ubiquitinated proteins and is a powerful tool when studying ubiquitin chain architecture or protein complexes. However, quantitative data clearly shows that antibody-based diGly enrichment methods offer superior depth of coverage, sensitivity, and are indispensable for translational research involving clinical tissues. The choice between these methods should be guided by the specific research question. For hypothesis-driven research on a specific protein or complex where genetic manipulation is feasible, ubiquitin tagging remains valuable. For discovery-phase projects aiming for system-wide coverage of the ubiquitinome in physiologically relevant models, antibody-based diGly enrichment is the unequivocally more powerful and appropriate technology.

Protein ubiquitination is one of the most prevalent post-translational modifications (PTMs), exerting critical regulatory control over virtually every cellular process, from protein degradation to signal transduction and DNA repair [9] [3]. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling arises from its ability to form diverse chain architectures, which encode specific biological functions. However, the low stoichiometry of ubiquitination and the complexity of ubiquitin chains make system-wide analysis challenging [3]. Among the methods developed to characterize the ubiquitinome, the antibody-based enrichment method targeting the ubiquitin remnant (diGLY approach) has emerged as a powerful technique for the identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites with high sensitivity and specificity [9]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the diGLY approach against alternative methods, focusing on its principle, experimental workflow, and performance data to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

The Core Principle of the diGLY Approach

The diGLY approach leverages a defining chemical signature left on proteins after they have been modified by ubiquitin. During protein ubiquitination, the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin is covalently attached to the ε-amine group of a lysine residue on a substrate protein [9]. When these ubiquitinated proteins are digested with the protease trypsin, a characteristic remnant is generated: the modified lysine residue retains a Gly-Gly (diGLY) moiety, resulting in a Lys-ε-Gly-Gly (K-ε-GG) motif on the peptide [9] [28]. This diGLY remnant has a mass shift of 114.04 Da, which can be detected by mass spectrometry (MS) [3].

The power of the method comes from the use of motif-specific antibodies that are precisely engineered to recognize and bind to this K-ε-GG remnant [9] [12]. This allows for the highly specific immunoaffinity enrichment of these low-abundance peptides from a complex background of unmodified peptides generated from a total cellular proteome digest. The enriched peptides are then identified and quantified using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [9]. It is critical to note that while this method is highly specific for ubiquitin-derived modifications, the identical C-terminal sequences of the ubiquitin-like proteins NEDD8 and ISG15 mean they also generate the same diGLY remnant upon trypsin digestion. Studies indicate that typically >95% of enriched diGLY peptides originate from ubiquitin rather than NEDD8 or ISG15 [9] [12]. A key advantage of this method is that it identifies the exact site of ubiquitination on substrate proteins, providing site-level resolution for downstream functional studies [9].

Detailed Experimental Workflow

A typical diGLY proteomics workflow involves multiple critical steps, from sample preparation to data analysis. The following protocol is adapted from established methods for SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture)-based quantitative diGLY proteomics, though label-free and isobaric chemical labeling approaches (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ) are equally applicable [9].

Step 1: Cell Culture and Metabolic Labeling (SILAC)

- Grow cells in SILAC media: "Light" media containing normal L-lysine and L-arginine, and "Heavy" media containing stable isotope-labeled (13C6, 15N2) L-lysine and (13C6, 15N4) L-arginine [9].

- Treat cells according to the experimental design (e.g., with a proteasome inhibitor like MG132 to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins, or with a pathway agonist like TNF) [9] [12].

Step 2: Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction

- Lyse cells in a denaturing buffer to inactivate deubiquitinases (DUBs) and preserve the native ubiquitinome. A standard lysis buffer contains:

- 8M Urea for denaturation.

- 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 8 as a buffering agent.

- 150mM NaCl to mimic physiological salt conditions.

- Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitors to prevent protein degradation and preserve PTMs.

- N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM, 5mM) to alkylate and inhibit cysteine-dependent DUBs (Note: prepare fresh) [9].

Step 3: Protein Digestion and Peptide Clean-up

- Reduce and Alkylate: Use dithiothreitol (DTT) to reduce disulfide bonds and iodoacetamide to alkylate cysteine residues.

- Digest Proteins: First, use LysC protease, which is active in high urea concentrations. Then, dilute the urea concentration and digest with trypsin to generate peptides with the K-ε-GG motif [9].

- Desalt Peptides: Use a reverse-phase solid-phase extraction cartridge (e.g., Sep-Pak C18). Peptides are eluted in an organic solvent like acetonitrile, dried, and reconstituted for the next step [9].

Step 4: Immunoaffinity Enrichment of diGLY Peptides

- Incubate the peptide mixture with anti-K-ε-GG antibody beads. Commercial kits (e.g., PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit) are available [9].

- After incubation, wash the beads extensively with cold buffer to remove non-specifically bound peptides.

- Elute the enriched diGLY peptides using a low-pH solution such as 0.1-0.5% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) or 5% acetic acid [9] [12].

Step 5: Mass Spectrometric Analysis and Data Processing

- Analyze the enriched peptides by LC-MS/MS. Recent advancements using Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) have demonstrated superior performance over traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA), nearly doubling identifications (e.g., ~35,000 diGLY peptides in a single run) and significantly improving quantitative accuracy [12].

- Identify peptides and localize ubiquitination sites by searching MS/MS spectra against a protein sequence database.

- For quantitative analysis, compare the signal intensities of "Light" and "Heavy" peptide pairs (SILAC) or use label-free quantification methods [9] [12].

Performance Comparison: diGLY vs. Alternative Methods

To objectively evaluate the diGLY approach, it is essential to compare its performance against other common strategies for ubiquitinome analysis. The primary alternatives are Ubiquitin (Ub) Tagging-based approaches and Ubiquitin-Binding Domain (UBD)-based enrichments.

Table 1: Comparison of Ubiquitinome Enrichment Methods

| Feature | diGLY Antibody-Based | Ub Tagging (e.g., His/Strep) | UBD-Based |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Enrichs tryptic peptides with K-ε-GG remnant [9] | Purifies proteins conjugated to epitope-tagged Ub [3] | Enriches proteins/peptides via Ub-binding domains [3] |

| Site Identification | Yes, provides exact site resolution [9] | Yes, but can be less effective for precise site mapping [3] | Variable, less effective for site identification [3] |

| Endogenous Context | Yes, studies native ubiquitination without genetic manipulation [9] [3] | No, requires expression of tagged ubiquitin, can cause artifacts [3] | Yes, can be used under physiological conditions [3] |

| Tissue/Animal Applicability | Excellent, directly applicable to any eukaryotic tissue [9] | Limited, infeasible for most patient or animal tissues [3] | Good, applicable to native tissues [3] |

| Throughput & Scalability | High, compatible with high-throughput MS platforms [12] | Moderate, limited by transfection/expression efficiency [3] | Lower, often challenged by low affinity and specificity [3] |

| Key Limitation | Cannot distinguish Ub from NEDD8/ISG15 (though contribution is low) [9] | Tagged Ub may not fully mimic endogenous Ub; high background [3] | Low affinity of single UBDs; linkage specificity can limit coverage [3] |

Quantitative data highlights the performance of the optimized diGLY workflow. A recent study using a DIA-based diGLY method identified over 35,000 distinct diGLY peptides in single measurements of MG132-treated cells, doubling the number obtained by traditional DDA methods [12]. Furthermore, the quantitative accuracy was significantly enhanced, with 45% of diGLY peptides showing coefficients of variation (CVs) below 20% across replicates, compared to only 15% with DDA [12].

Table 2: Representative Quantitative Performance of diGLY Workflows

| Method | Peptide Input | Number of diGLY Peptides Identified | Quantitative Precision (CV < 20%) | Key Advancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|