Ubiquitination and Phosphorylation Crosstalk: Integrating Signals for Cellular Control and Therapeutic Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the intricate crosstalk between ubiquitination and phosphorylation, two paramount post-translational modifications (PTMs) governing eukaryotic cell signaling.

Ubiquitination and Phosphorylation Crosstalk: Integrating Signals for Cellular Control and Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the intricate crosstalk between ubiquitination and phosphorylation, two paramount post-translational modifications (PTMs) governing eukaryotic cell signaling. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational mechanisms of this interplay, from phosphodegrons to reciprocal enzyme regulation. We delve into cutting-edge methodological approaches, including multi-PTM proteomics and systems biology modeling, that are revolutionizing the study of signaling networks in health and disease. The review further addresses the challenges of targeting this crosstalk therapeutically, highlighting progress in drug discovery against the ubiquitin-proteasome system and kinases. Finally, we validate these concepts through compelling case studies in oncology and immunology, synthesizing key takeaways to illuminate future directions for biomedical and clinical research.

The Fundamental Language of Cellular Signals: Defining Ubiquitination and Phosphorylation Crosstalk

In the intricate landscape of cellular biochemistry, post-translational modifications (PTMs) serve as fundamental regulatory mechanisms that control protein function, localization, and stability. Among these, phosphorylation and ubiquitination represent two of the most crucial and widespread enzymatic cascades governing eukaryotic cell signaling. While historically studied in isolation, emerging research reveals extensive crosstalk between these pathways, creating sophisticated regulatory networks that maintain cellular homeostasis [1]. Phosphorylation, characterized by its rapid, reversible nature, primarily regulates protein activity and signal transduction. In contrast, ubiquitination, with its diverse outcomes ranging from proteasomal degradation to non-proteolytic signaling, provides broader functional consequences. Understanding the distinct characteristics, enzymatic mechanisms, and intersecting dynamics of these cascades is essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to modulate pathological signaling pathways in cancer, neurodegeneration, and other diseases.

The Phosphorylation Cascade: Architecture and Mechanism

Fundamental Enzymatic Components

The phosphorylation cascade involves a coordinated sequence of enzymatic reactions that transfer phosphate groups to specific target proteins. This system relies on three key components that work in concert to ensure signaling specificity and precision.

Kinases: These enzymes catalyze the transfer of a gamma-phosphate group from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to specific amino acid residues on substrate proteins, primarily targeting serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues [1]. The human genome encodes approximately 500 protein kinases, each exhibiting specific substrate recognition patterns. Kinases often function within hierarchical cascades, where one kinase phosphorylates and activates the next kinase in the sequence, resulting in signal amplification.

Phosphatases: These enzymes provide the necessary counter-regulation by removing phosphate groups from phosphorylated proteins, thereby terminating signals or reversing functional states [1]. This opposing activity creates a dynamic, reversible modification system that can rapidly respond to changing cellular conditions. The balanced action of kinases and phosphatases allows for precise temporal control over protein function.

Protein Substrates: The targets of phosphorylation cascades include a diverse array of structural and regulatory proteins. A single phosphorylation event can induce conformational changes that alter protein activity, subcellular localization, or interaction with binding partners [1]. Many proteins contain multiple phosphorylation sites, enabling complex regulatory patterns and integration of multiple signals.

Molecular Recognition and Catalysis

Enzyme-substrate interactions in phosphorylation cascades depend on highly specific molecular recognition mechanisms that ensure signaling fidelity:

Active Site Complementarity: Kinases and phosphatases employ specialized active sites with geometric and chemical complementarity to their specific protein substrates, following either lock-and-key or induced-fit binding models [2] [3]. This complementarity ensures precise substrate selection among thousands of cellular proteins.

Binding Interactions: Multiple non-covalent forces stabilize enzyme-substrate complexes, including electrostatic interactions with charged amino acid side chains, hydrogen bonding with polar residues, and hydrophobic interactions that exclude water from binding interfaces [4]. The cumulative effect of these interactions provides the binding energy necessary for substrate specificity and catalytic efficiency.

Catalytic Mechanisms: Phosphorylation enzymes employ several catalytic strategies, including metal ion catalysis using Mg²⁺ or Mn²⁺ to orient ATP and stabilize negative charges, general acid-base catalysis to facilitate proton transfer, and covalent catalysis through transient phosphoenzyme intermediates [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination Cascades

| Characteristic | Phosphorylation Cascade | Ubiquitination Cascade |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Classes | Kinases, Phosphatases | E1, E2, E3, Deubiquitinases |

| Energy Source | ATP | ATP |

| Modification Site | Ser, Thr, Tyr (His) | Lys (Ser, Thr, N-terminus) |

| Chemical Bond | Phosphoester | Isopeptide |

| Reversibility | Highly reversible | Reversible (by DUBs) |

| Primary Outcomes | Altered protein activity, signaling | Degradation, signaling, trafficking |

| Signal Amplification | Kinase cascades | E2/E3 combinatorial complexity |

The Ubiquitination Cascade: Architecture and Mechanism

The Three-Step Enzymatic Pathway

Ubiquitination employs a sophisticated three-enzyme cascade that conjugates the small protein modifier ubiquitin to substrate proteins, enabling diverse regulatory outcomes beyond mere protein degradation.

E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): The cascade initiates with E1, which activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thioester bond between its catalytic cysteine and the C-terminus of ubiquitin [1]. The human genome encodes only two E1 enzymes, creating an initial bottleneck in the ubiquitination pathway.

E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): Activated ubiquitin is transferred from E1 to the catalytic cysteine of an E2 enzyme, maintaining the thioester linkage [1]. With approximately 40 E2s in humans, this tier begins to introduce specificity, with different E2s determining the linkage type and chain topology during ubiquitination [5].

E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): The final and most diverse tier consists of E3 ligases, which number over 600 in humans and provide substrate specificity by simultaneously binding E2~Ub complexes and target proteins [1]. E3s facilitate the direct transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to substrate lysine residues, forming an isopeptide bond. Some E2/E3 pairs can also modify serine, threonine, or the protein N-terminus, expanding the regulatory potential of this pathway [5].

Diversity of Ubiquitin Signals and Outcomes

The ubiquitination cascade generates remarkably diverse signals that dictate distinct functional consequences for modified proteins:

Monoubiquitination: Single ubiquitin attachments typically regulate protein trafficking, endocytosis, and histone function without targeting substrates for degradation [1].

Multi-monoubiquitination: Multiple single ubiquitin molecules attached to different lysines on the same substrate can serve as signals for endocytic sorting and internalization of cell surface receptors [1].

Polyubiquitination: Ubiquitin chains formed through specific lysine linkages create topological codes recognized by different cellular machineries. K48-linked chains predominantly target proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains mediate non-proteolytic functions in DNA repair, kinase activation, and inflammatory signaling [1].

Atypical Linkages: Mixed or branched chains involving K6, K11, K27, K29, or K33 residues provide additional regulatory complexity with specialized functions in ER-associated degradation, immune regulation, and mitophagy [1].

Comparative Analysis: Key Structural and Functional Distinctions

Enzymatic Architecture and Energetics

The fundamental architectures of phosphorylation and ubiquitination cascades reveal distinct evolutionary strategies for cellular regulation. Phosphorylation employs a binary enzyme system of kinases and phosphatases that directly add and remove modifications in a relatively straightforward manner [1]. This streamlined architecture enables rapid, reversible signaling well-suited for fast-responsive regulatory circuits. In contrast, the ubiquitination cascade operates through a three-tiered enzymatic hierarchy (E1-E2-E3) that provides exceptional combinatorial complexity through the pairing of a limited number of E1 and E2 enzymes with a vast repertoire of E3 ligases [1]. This arrangement allows for exquisite substrate specificity and diverse output signals from a limited genomic investment.

Both systems are ATP-dependent processes, but they utilize this energy currency differently. Phosphorylation consumes one ATP molecule per modification event to directly drive the transfer of a phosphate group to the substrate [2]. Ubiquitination requires ATP at the initial activation step where E1 activates ubiquitin, with this energy subsequently preserved through high-energy thioester intermediates that are passed along the enzymatic cascade [1]. This energy conservation mechanism allows multiple ubiquitin transfers from a single activation event, particularly during chain elongation.

Kinetics and Regulatory Dynamics

The temporal dynamics and regulatory properties of these cascades differ significantly, reflecting their distinct biological roles:

Modification Reversibility: Phosphorylation is highly dynamic, with rapid kinase and phosphatase activities enabling millisecond-to-second timescale regulation ideal for signal transduction and metabolic control [1]. Ubiquitination reversal by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) typically occurs on slower timescales, particularly when regulating irreversible processes like proteasomal degradation [1].

Signal Amplification: Phosphorylation cascades, such as the MAPK pathway, provide strong signal amplification through sequential kinase activation, where each enzyme activates multiple copies of the next component [1]. Ubiquitination achieves signal diversification through combinatorial E2-E3 pairing, with single E3 ligases potentially modifying hundreds of substrate molecules and creating different ubiquitin topologies with distinct functional consequences [1].

Modification Diversity: While phosphorylation is limited to the addition of a single phosphate group per modified residue, ubiquitination creates complex signals through chain elongation and branching, with different linkage types encoding distinct functional instructions [1]. This allows a single modification system to regulate multiple cellular processes through topological variation.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Modification Properties

| Property | Phosphorylation | Ubiquitination |

|---|---|---|

| Modifying Enzymes in Humans | ~500 Kinases | 2 E1, ~40 E2, >600 E3 |

| Demodifying Enzymes in Humans | ~150 Phosphatases | ~100 DUBs |

| Modification Sites | Ser, Thr, Tyr, His | Primarily Lys |

| Modification Size | 80 Da (phosphate) | 8.5 kDa (ubiquitin) |

| Representative Turnover Rates | Seconds to minutes | Minutes to hours |

| Common Chain Types | Single phosphate | K48, K63, K11, K29, etc. |

Experimental Methodologies for Cascade Analysis

Core Techniques for Phosphorylation Studies

Investigating phosphorylation cascades requires specialized methodologies to capture the transient nature of these modifications:

Western Blotting with Phospho-Specific Antibodies: This fundamental technique allows detection of phosphorylation changes at specific sites using antibodies that recognize phosphorylated serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues [6]. When combined with appropriate stimulation conditions and pharmacological inhibitors, this approach provides semiquantitative data on phosphorylation dynamics.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Phosphoproteomics: Global phosphorylation analysis employs phosphopeptide enrichment techniques such as immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) or titanium dioxide (TiO₂) chromatography, followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify and quantify thousands of phosphorylation sites simultaneously [7]. Stable isotope labeling methods enable precise temporal tracking of phosphorylation events in response to cellular stimuli.

Kinase Activity Assays: Direct measurement of kinase function utilizes radioactive ATP (³²P-ATP) or ATP analogs in in vitro kinase reactions with recombinant or immunoprecipitated kinases and their substrates. These assays provide direct information about enzymatic activity rather than merely phosphorylation status.

Core Techniques for Ubiquitination Studies

Ubiquitination research employs distinct methodological approaches tailored to the complexity of this modification:

Co-immunoprecipitation and Ubiquitin Detection: This classic approach involves immunoprecipitating a protein of interest under denaturing conditions to preserve ubiquitin conjugates, followed by western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies to detect polyubiquitinated species [6]. Modification with tagged ubiquitin constructs (HA-, His-, or FLAG-ubiquitin) enhances detection specificity and sensitivity.

diGly Proteomics: This global ubiquitinome profiling technique exploits the tryptic digestion signature of ubiquitinated proteins, which generates a characteristic di-glycine remnant on modified lysines. Enrichment with diGly-specific antibodies followed by MS analysis enables system-wide identification of ubiquitination sites [7].

In Vitro Reconstitution Assays: Defined biochemical systems with purified E1, E2, and E3 enzymes allow precise dissection of ubiquitination mechanisms without confounding cellular factors [5]. These approaches have revealed how membrane composition regulates E2 activity and how specific E3 ligases recognize their substrates.

Crosstalk Mechanisms: Integration of Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination

Molecular Mechanisms of PTM Interplay

The extensive crosstalk between phosphorylation and ubiquitination creates sophisticated regulatory circuits that enhance cellular signaling capabilities:

Phosphodegrons: These specific phosphorylation motifs serve as recognition signals for E3 ubiquitin ligases, directly linking kinase activity to substrate ubiquitination and degradation [7] [1]. Well-characterized examples include the β-TrCP recognition motif in IκBα and the SCF ubiquitination signals in cell cycle regulators. Phosphodegron-mediated regulation provides irreversibility to cell cycle transitions and transcriptional responses.

E3 Ligase Regulation by Phosphorylation: Many E3 ubiquitin ligases are themselves regulated by phosphorylation events that control their catalytic activity, substrate specificity, or subcellular localization [1]. For instance, phosphorylation of the E3 ligase Cbl on tyrosine 371 induces a conformational change that exposes its RING domain, enabling E2 binding and activation of its ubiquitination function [1].

Kinase Regulation by Ubiquitination: Conversely, ubiquitination directly regulates kinase activity through both degradative and non-degradative mechanisms [1]. While K48-linked ubiquitination typically terminates kinase signaling through proteasomal degradation, K63-linked ubiquitination can directly activate kinases such as NIK in the NF-κB pathway, demonstrating the bidirectional nature of PTM crosstalk.

Systems-Level Integration and Emerging Concepts

Recent research has revealed additional layers of complexity in phosphorylation-ubiquitination crosstalk:

Conservation Patterns: Global proteomic analyses indicate that phosphorylation sites co-occurring with ubiquitination show significantly higher evolutionary conservation than phosphorylation sites in general, suggesting strong functional selection for these integrated regulatory nodes [7].

Hierarchical Regulation: In the EGFR/MAPK pathway, phosphorylation events precede and direct ubiquitination at multiple levels—receptor activation initiates Cbl-mediated ubiquitination, which in turn regulates downstream signaling dynamics through controlled receptor internalization and degradation [1].

Pathway Switching Mechanisms: Recent findings demonstrate that phosphorylation can redirect E2 enzyme specificity, as shown by RSK1-mediated phosphorylation of UBE2L6, which switches its function from ISG15 conjugation to ubiquitin conjugation, consequently altering its role in immune signaling [8].

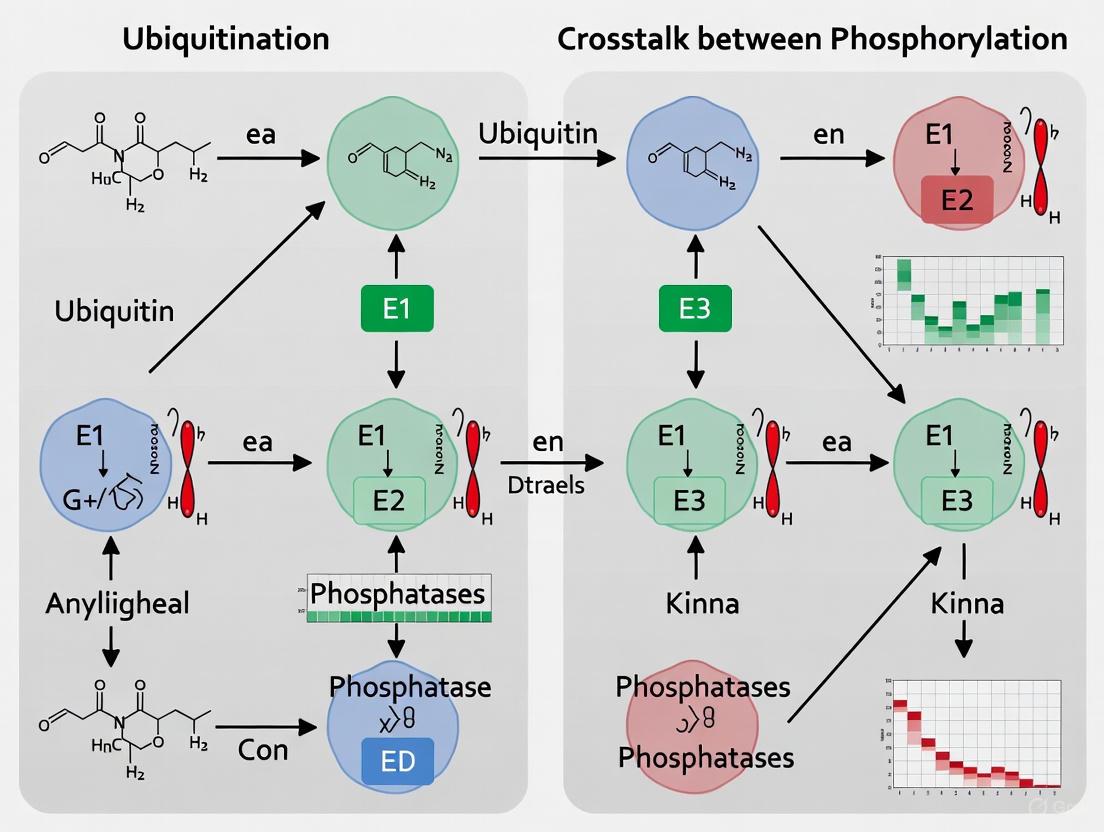

Figure 1: Core Crosstalk Mechanisms Between Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination Cascades. This diagram illustrates how phosphorylation events can create recognition motifs (phosphodegrons) for E3 ubiquitin ligases, while ubiquitination reciprocally regulates kinase activity and stability through both degradative and non-degradative mechanisms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Phosphorylation-Ubiquitination Crosstalk

| Reagent/Solution | Primary Function | Application Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detect specific phosphorylation events | Western blotting, immunofluorescence | Validation of target specificity required |

| Ubiquitin-Tagging Systems (HA-, His-, FLAG-Ub) | Track protein ubiquitination | Co-IP, pulldown assays | Use under denaturing conditions for direct ubiquitination |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (MG132, Bortezomib) | Block proteasomal degradation | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins | Can induce cellular stress responses |

| Kinase Inhibitors | Perturb phosphorylation signaling | Functional studies, therapeutic screening | Watch for off-target effects on related kinases |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors | Preserve phosphorylation states | Protein extraction, enzymatic assays | Cocktails often needed for complete inhibition |

| E1/E2/E3 Recombinant Proteins | Reconstitute ubiquitination in vitro | Mechanistic studies, screening | Require optimized buffer conditions |

| diGly-Specific Antibodies | Enrich ubiquitinated peptides | Ubiquitinome profiling by MS | Specific for tryptic digests with Gly-Gly remnant |

| Active Kinases/Phosphatases | Modify phosphorylation in vitro | Enzyme assays, substrate validation | Require proper activation/cofactors |

The comparative analysis of phosphorylation and ubiquitination cascades reveals both striking parallels and fundamental distinctions in their biochemical logic and cellular implementation. While both represent ATP-dependent enzymatic cascades that dynamically modify proteins to regulate their function, they employ markedly different architectural principles—phosphorylation utilizes a direct binary system of opposing enzymes, whereas ubiquitination employs a three-tiered hierarchical cascade with exceptional combinatorial potential [1]. These structural differences underlie their specialized biological roles: phosphorylation excels at rapid, reversible information transfer for signal transduction and metabolic control, while ubiquitination provides diverse functional outcomes ranging from targeted destruction to complex assembly regulation.

The emerging paradigm of extensive crosstalk between these systems demonstrates how eukaryotic cells integrate these pathways to create sophisticated regulatory networks with enhanced information-processing capabilities [1] [9]. The molecular integration through mechanisms such as phosphodegrons, reciprocal enzyme regulation, and pathway switching creates layered control systems that enable precise cellular decision-making. For researchers and drug developers, understanding these interconnected networks provides exciting opportunities for therapeutic intervention, particularly in cancer and immune disorders where both phosphorylation and ubiquitination pathways are frequently dysregulated. Future research will undoubtedly continue to reveal novel aspects of this complex biochemical interplay, expanding our understanding of cellular regulation and creating new avenues for manipulating these fundamental processes in human disease.

{article}

Beyond Degradation: The Diverse Functional Outcomes of Different Ubiquitin Chain Linkages

Ubiquitination, once recognized primarily as a signal for proteasomal degradation, is now understood to govern a vast array of non-degradative cellular processes. The functional outcome of ubiquitination is largely dictated by the topology of the polyubiquitin chain assembled on a substrate protein. This article provides a comparative analysis of the distinct biological functions mediated by different ubiquitin linkage types, with a special emphasis on K48-linked degradative signals versus the non-degradative roles of K63-linked and branched chains. Framed within the context of crosstalk with phosphorylation, we detail the experimental methodologies and reagent toolsets that are enabling researchers to decode the complex logic of ubiquitin signaling in health and disease.

Ubiquitin Chain Linkages: A Functional Spectrum

Ubiquitin can be conjugated to substrate proteins as a monomer or as a polymer, forming chains through one of its seven internal lysine (K) residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or its N-terminal methionine (M1) [10] [11]. The architecture of these chains dictates their function, creating a specialized signaling system. Homotypic chains, linked uniformly through the same residue, were the first to be characterized. However, the ubiquitin code is further complicated by heterotypic chains, which include mixed chains (more than one linkage type, but each ubiquitin modified at only one site) and branched chains (comprised of ubiquitin subunits simultaneously modified on at least two different sites) [10] [12]. The following table summarizes the well-established functions of major ubiquitin chain types.

Table 1: Comparative Functions of Major Ubiquitin Chain Linkages

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Key Biological Processes | Representative E3 Ligases / Complexes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal Degradation [11] | Protein turnover, cell cycle progression, metabolic regulation [11] [13] | APC/C, UBR5 [10] |

| K63-linked | Signal Transduction, protein-protein interactions, endocytosis, DNA repair [14] [11] [13] | NF-κB activation, innate and adaptive immunity, autophagy [14] [13] | TRAF6, TRAF2, cIAP1/2 [14] [13] |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal Degradation (especially in concert with K48) [15] | Cell cycle regulation, mitotic progression, proteotoxic stress response [15] | APC/C (with UBE2S) [10] [15] |

| K11/K48-branched | Priority Degradation Signal [15] | Accelerated degradation of cell cycle regulators and misfolded proteins [15] | APC/C (with UBE2C and UBE2S) [10] [15] |

| K29/K48-branched | Proteasomal Degradation [10] | Ubiquitin Fusion Degradation (UFD) pathway [10] | Ufd4 and Ufd2 (in yeast) [10] |

| K48/K63-branched | Degradation & Signaling Switching [10] | NF-κB signaling, apoptotic response, p97/VCP processing [10] | TRAF6 & HUWE1, ITCH & UBR5 [10] |

| M1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB Activation, inflammatory signaling [14] | Innate immunity, cell death regulation [14] | HOIP (LUBAC complex) [14] |

Crosstalk with Phosphorylation: A Central Signaling Nexus

The ubiquitin system does not operate in isolation; it engages in extensive bidirectional crosstalk with other post-translational modifications (PTMs), most notably phosphorylation [7] [16] [17]. This interplay is a fundamental mechanism for increasing the specificity and combinatorial logic of cellular signaling.

One primary mode of crosstalk occurs when phosphorylation directly primes a substrate for ubiquitination. The canonical example is the phosphodegron, a specific motif where phosphorylation creates a binding site for a specialized E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to the substrate's ubiquitylation and degradation [7]. This mechanism is central to cell cycle control.

Conversely, ubiquitination can regulate components of the phosphorylation machinery. For instance, K63-linked ubiquitination of RIPK2 following NOD2 receptor activation creates a scaffold that facilitates the recruitment and activation of the TAK1 and IKK kinase complexes, which in turn phosphorylate downstream targets to activate NF-κB signaling [13].

Global proteomic studies have quantified this relationship, revealing that phosphorylation sites found on ubiquitylated protein isoforms are significantly more evolutionarily conserved than the broader set of phosphorylation sites, underscoring their functional importance [7]. The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of this PTM crosstalk.

Ubiquitination and Phosphorylation Crosstalk

Methodologies for Decoding Ubiquitin Signaling

Studying ubiquitination presents unique challenges due to its low stoichiometry, the diversity of chain architectures, and its dynamic nature. The field has developed sophisticated methods to overcome these hurdles.

Enrichment and Detection Strategies

A critical first step is the specific enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins or peptides from complex lysates. The table below catalogs key reagent solutions essential for this research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Principle | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) [13] [12] | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitinated proteins; available in pan-specific and linkage-specific (K48, K63) variants. | Protects chains from DUBs; enables detection of endogenous protein ubiquitination in high-throughput assays (e.g., PROTAC screening). |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies [11] [13] | Immuno-enrichment and detection of ubiquitin chains with defined linkages (e.g., K48, K63, K11). | Useful for Western blotting, immunofluorescence, and immunoprecipitation; can be applied to tissue samples without genetic manipulation. |

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin (e.g., His, Strep, HA) [7] [11] | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates after overexpression of tagged ubiquitin. | Enables system-wide profiling of ubiquitination sites (ubiquitinome) via mass spectrometry. |

| DiGly Antibody (GG-K⁰ antibody) [7] | Enriches for tryptic peptides containing the di-glycine remnant left on modified lysine after trypsin digestion. | The gold standard for mass spectrometry-based mapping of ubiquitination sites on a proteome-wide scale. |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs [12] | Enzymatic tools to confirm linkage identity or to selectively cleave specific chains in vitro. | Used in conjunction with Western blotting or mass spectrometry to validate chain topology. |

| Mutant Ubiquitin Plasmids (K-to-R mutants) [13] | In vivo expression of ubiquitin where a specific lysine is mutated to arginine to prevent formation of that linkage. | Allows functional dissection of the role of a specific ubiquitin linkage in a pathway. |

A prominent application of TUBEs is the investigation of context-dependent ubiquitination. For example, the endogenous kinase RIPK2 can be modified with either K63-linked chains upon inflammatory stimulation (e.g., with L18-MDP) or K48-linked chains when targeted by a PROTAC degrader. As demonstrated in a 2025 study, K63- and K48-TUBEs can selectively capture these distinct ubiquitination events in a high-throughput format, providing a powerful tool for characterizing targeted protein degradation therapeutics [13]. The workflow for such an analysis is detailed below.

TUBE-Based Ubiquitination Assay Workflow

Structural Biology and In Vitro Reconstitution

Understanding how ubiquitin chains are recognized at an atomic level has been revolutionized by structural techniques. A landmark 2025 cryo-EM study of the human 26S proteasome in complex with a K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chain revealed a multivalent recognition mechanism [15]. The structures showed that the proteasome uses a novel binding site formed by RPN2 and RPN10 to engage the K11-linked branch, in addition to the canonical K48-linkage binding site [15]. This explains the "priority degradation signal" conferred by K11/K48-branched chains.

To conduct such studies, the synthesis of defined ubiquitin chains is essential. Branched ubiquitin trimers and tetramers of specific linkages (e.g., K48/K63) can be assembled enzymatically using a combination of linkage-specific E2 enzymes and engineered ubiquitin mutants (e.g., Ub¹⁻⁷²) to control the order of linkage addition [12]. Alternatively, total chemical synthesis and genetic code expansion strategies allow for the incorporation of non-hydrolysable bonds or spectroscopic probes, providing powerful reagents for mechanistic and biophysical studies [12].

Implications for Drug Development and Disease

The intricate relationship between ubiquitin linkages and cellular outcomes has direct translational relevance, particularly in immunology and oncology. In immune signaling, K63-linked and linear ubiquitination are critical for activating NF-κB and MAPK pathways downstream of innate immune receptors [14] [13]. Consequently, inhibiting the enzymes that write (e.g., TRAF6), read, or erase (DUBs) these chains is a promising therapeutic strategy for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [13].

In cancer, the targeted protein degradation (TPD) paradigm, exemplified by PROTACs, deliberately hijacks the K48-linked ubiquitination machinery to induce the degradation of oncogenic proteins [13]. The efficiency of a PROTAC is fundamentally linked to its ability to induce polyubiquitination with the correct linkage. High-throughput TUBE-based assays are now being deployed to screen for effective PROTAC molecules by directly measuring their ability to induce K48-linked ubiquitination of the target protein [13]. Furthermore, the discovery that branched chains like K11/K48 can serve as superior degradation signals suggests that inducing specific chain topologies could be the next frontier in optimizing TPD therapeutics [15].

{/article}

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) represent a fundamental layer of regulation in cellular signaling, with phosphorylation and ubiquitination standing as two of the most prevalent and functionally interconnected mechanisms. This guide objectively compares the molecular logic by which these PTMs interact to control protein stability through phosphodegrons—specific amino acid motifs where phosphorylation acts as a signal for subsequent ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. We dissect the experimental evidence for canonical sequential modification, competitive residue mechanisms, and the emerging role of basic residues as electrostatic modulators. Supported by quantitative data and detailed methodologies, this review provides a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand and target these regulatory nodes in disease pathways, particularly in cancer and targeted protein degradation therapies.

The functional diversity of the human proteome is vastly expanded by post-translational modifications (PTMs), with phosphorylation and ubiquitination representing two of the most dynamic and interconnected regulatory systems. Ubiquitination-phosphorylation crosstalk is a recurring theme in eukaryotic cell signaling, enabling precise, reversible, and rapid control over protein stability, activity, and localization [1] [17]. The proteome-wide, mass spectrometry-based assessment in budding yeast revealed the scale of this interplay, identifying 466 proteins that were simultaneously modified by both phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Notably, around half of the ~2,000 phosphorylation sites on these proteins were exclusive to the ubiquitin-modified proteoforms, suggesting specialized regulatory roles [7].

At the heart of this crosstalk lies the phosphodegron, a specific motif within a protein that, upon phosphorylation, is recognized by a specialized E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to the substrate's polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome [18] [19]. These motifs function as critical integration points for cellular signals, translating upstream kinase activity into controlled protein turnover. The mutation of genes encoding E3 ligases like FBXW7 or the phosphodegrons in their substrates, such as NOTCH1, is a frequent occurrence in cancers, underscoring the therapeutic importance of understanding these mechanisms [20] [18]. This guide systematically compares the distinct molecular strategies cells employ to implement phosphodegron-based regulation, providing a side-by-side analysis of their mechanisms, key players, and experimental evidence.

Comparative Mechanisms of Phosphodegron Operation

The term "phosphodegron" encompasses several distinct mechanistic classes of phosphorylation-dependent degradation signals. The following sections and Table 1 provide a structured comparison of these mechanisms, supported by quantitative data from key studies.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Phosphodegron Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Molecular Logic | Example E3 Ligase | Example Substrate(s) | Key Regulatory Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical Sequential | Phosphorylation creates a direct binding site for a specific E3 ligase [18]. | FBXW7 (SCF complex) [20] | Cyclin E, c-Myc, KLF5, NOTCH1 [20] | Requires a consensus motif (e.g., FBXW7: Thr-Pro-Pro-Xaa-Ser); often involves multiple kinases in a sequential manner [20]. |

| Kinase-Integrated | The activating kinase is directly recruited to or is a part of the E3 ligase complex [1]. | Cbl (RING-type E3) [1] | EGFR (EGF Receptor) [1] | Kinase activity (EGFR itself) and E3 ligase recruitment are coupled; involves allosteric activation of the E3 ligase [1]. |

| Phospho-Inhibited | Phosphorylation blocks the degron, stabilizing the protein [19]. | Specific E3 complexes for EphB4 [19] | EphB4 Receptor [19] | Phosphorylation and ubiquitylation are alternative fates for the same motif, establishing a biological switch [19]. |

| Electrostatically Modulated | Basic residues near the phosphosite modulate phosphate group properties and E3 binding affinity [21]. | Potentially SCF-Cdc4 [22] | c-Src (Unique domain) [21] | Local electrostatic network fine-tunes phosphodegron function; pKa of phosphate groups is a key parameter [21]. |

Canonical Sequential Phosphodegrons and the FBXW7 Paradigm

The best-characterized mechanism involves a strict sequential process where phosphorylation of a degron motif precedes and is absolutely required for E3 ligase binding. A prime example is the E3 ligase FBXW7 (also known as Cdc4), a critical tumor suppressor. FBXW7 recognizes a consensus phosphodegron sequence, Thr-Pro-Pro-Xaa-Ser, where both the threonine and serine residues must be phosphorylated for high-affinity binding to the WD40 domain of FBXW7 [20]. This mechanism is exemplified by its regulation of oncoproteins like cyclin E (CCNE1) and c-Myc. The structural basis for this interaction was revealed by crystallography studies of the FBXW7-Skp1 complex with a bisphosphorylated cyclin E1 peptide, demonstrating how phosphorylation induces a complementary fit with the ligase [20].

A systems-level study using a ratiometric protein degradation assay discovered 19 novel FBXW7-binding phosphodegrons in proteins involved in transcription (ETV5, KLF4), chromatin regulation (ARID4B, KMT2D), and cytoskeletal functions (MAP2) [20]. This research highlighted the partnership between FBXW7 and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs), showing that the degradation of substrates like ARID4B and JAZF1 was diminished upon application of MAPK-specific inhibitors. This demonstrates that MAPKs often serve as the "priming" kinases for FBXG7 substrates, expanding our understanding of how extracellular signals can directly modulate protein stability [20].

Competitive Residues and Phospho-Inhibited Degrons

In a contrasting mechanism, phosphorylation can sometimes inhibit degradation. In these "phospho-inhibited" degrons, modification of a specific residue blocks the interaction with the E3 ligase, thereby stabilizing the protein. This creates a competitive switch where a single residue can be targeted for either stabilization (via phosphorylation) or destabilization (via ubiquitination) [19].

Research on the EphB4 receptor kinase identified a phospho-inhibited degron where phosphorylation at a specific site prevents its own ubiquitination and degradation. This mechanism allows for precise control over the abundance of this angiogenic kinase, and its dysregulation contributes to oncogenesis [19]. This competitive logic is a powerful regulatory switch, enabling cellular signals to directly oppose degradation.

The Role of Basic Residues in Electrostatic Modulation

Beyond the binary switch of phospho-activation/inhibition, the local protein environment can fine-tune degron function. Studies on the Unique domain of c-Src revealed that basic residues (lysine and arginine) located near phosphorylation sites can form specific electrostatic interactions with the introduced phosphate group [21].

These interactions can modulate the acidity (pKa) of the phosphate and introduce local conformational restrictions, effectively coupling various phosphosites into a functional unit. For instance, in c-Src, the phosphorylation sites T37, S43, and S75 all have nearby basic residues that influence their properties. Mutation of arginine 78 (R78) to alanine increased the pKa of the nearby pS75 phosphate group from 6.03 to 6.15, indicating a direct electrostatic interaction that stabilizes the phosphorylated state [21]. This electrostatic network represents a sophisticated layer of regulation that can influence the affinity of a phosphodegron for its cognate E3 ligase, adding a dimension of fine-tuning to the degradation signal.

Experimental Data and Quantitative Analysis

The discovery and validation of phosphodegrons rely on a suite of biochemical and cell-based assays. The quantitative data from these experiments are crucial for comparing the strength and regulation of different degrons.

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Key Phosphodegron and Crosstalk Studies

| Study System / Assay | Key Quantitative Findings | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Ratiometric Degradation Assay (FBXW7 substrates) [20] | Identified 19 novel FBXW7 phosphodegrons; Degradation of probes (e.g., CycECO) was dependent on FBXW7 overexpression and inhibited by MG132. | Demonstrates partnership between MAPKs and FBXW7; suggests a multitude of substrates may simultaneously mediate FBXW7's tumor suppressor function. |

| Global Yeast PTM Analysis [7] | 466 proteins co-modified by phosphorylation and ubiquitination; 2,100 phosphorylation sites co-occurring with 2,189 ubiquitylation sites. | Phosphorylation sites found co-occurring with ubiquitylation were more highly conserved than the entire set of phosphorylation sites (P = 0.0027). |

| pKa Measurement of c-Src Phosphosites [21] | pKa values of phosphoresidues: pT37 (6.10), pS43 (5.80), pS75 (6.03). R78A mutation increased pS75 pKa to 6.15. | Basic residues form specific electrostatic networks to fine-tune phosphate group properties, potentially affecting E3 ligase binding affinity. |

| Cdk1 Phosphorylation of Ame1 [22] | Ame1 contains a cluster of 4 minimal Cdk1 sites (Thr31, Ser41, Ser45, Ser52/53); Phosphorylation activates SCF-Cdc4 phosphodegrons. | Links core cell cycle machinery (Cdk1) to inner kinetochore assembly, ensuring timely subunit turnover. |

Key Experimental Protocol: PTM-Enhanced (PTMe) Pull-down Assay

To functionally study phosphodegrons and their associated degradation complexes, a novel Post-translational Modification–enhanced (PTMe) Pull-down method has been developed. This protocol integrates kinase and ubiquitination assays into a single pull-down step, offering a significant advantage over traditional, separate co-immunoprecipitation and in vitro modification assays [19].

Workflow Overview:

- Bait Design: A synthetic, biotin-tagged peptide containing the native sequence of the putative phosphodegron is generated.

- PTM-Enhanced Incubation: The bait peptide is incubated with cell extracts, which provide a native source of active kinases, E1/E2/E3 enzymes, and ubiquitin. The reaction is supplemented with ATP (phosphate donor), ubiquitin, and essential cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺, Mn²⁺) to actively enhance phosphorylation and ubiquitination events on the bait.

- Capture and Analysis: The biotinylated bait and its recruited protein complexes are pulled down using streptavidin-magnetic beads. The complexes can then be analyzed by western blotting (e.g., for specific E3 ligases) or mass spectrometry for proteomic profiling [19].

This method is particularly powerful because it recapitulates the functional dependency between phosphorylation and ubiquitination, allowing for the simultaneous discovery and validation of the degradation complex recruited to a specific phosphodegron under different cellular treatment conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and their applications for studying phosphodegrons and PTM crosstalk, as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Phosphodegron Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Specifications & Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biotin-tagged pDegron Peptide | HPLC-grade synthetic peptide; serves as the assay bait to recruit degradation complexes. | PTMe pull-down assay for identifying E3 ligases [19]. |

| Recombinant Ubiquitin | Source of ubiquitin moiety for in vitro ubiquitination reactions. | PTMe pull-down assay; standard in vitro ubiquitination assays [19]. |

| SCF Complex Inhibitors | e.g., MLN4924 (NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor); blocks activity of cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) like SCF. | Validating the involvement of SCF complexes in substrate degradation [20]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | e.g., MG132; inhibits the 26S proteasome, causing accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins. | Confirming UPS-mediated degradation in cell-based or in vitro assays [20] [19]. |

| Kinase-Specific Inhibitors | Inhibitors for MAPKs (ERK, JNK, p38), Cdk1, AKT, etc.; used to identify the priming kinase. | Determining kinase responsible for phosphodegron activation (e.g., MAPK for FBXW7 substrates) [20] [23]. |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Antibodies recognizing phosphorylated degron motifs (e.g., pThr-Pro-Pro-Xaa-pSer). | Validating in vivo phosphorylation of the degron by western blot or immunofluorescence [20]. |

| Ubiquitin Remnant Antibody | Antibody recognizing diglycine (diGly) remnant on lysine after tryptic digest. | Mass spectrometry-based site-specific mapping of ubiquitylation sites [7]. |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Logic

The molecular mechanisms of phosphodegrons are integrated into larger signaling networks, enabling dynamic cellular responses. The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making pathways that govern protein stability through phosphodegron regulation.

Figure 1: Core Signaling Pathway of a Canonical Phosphodegron. An upstream signal activates a specific kinase, which phosphorylates the degron motif on the substrate protein. This creates a binding site for an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which then polyubiquitinates the substrate, targeting it for proteasomal degradation.

The experimental workflow for discovering and validating these interactions, particularly using modern, integrated methods, can be visualized as a multi-stage process.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Phosphodegron Analysis. The process begins with the identification of a putative degron sequence, followed by the synthesis of a biotin-tagged bait peptide. This bait is used in a PTM-enhanced pull-down with cell extracts to recruit endogenous kinases and E3 ligases. The recruited protein complexes are then analyzed, typically by mass spectrometry for discovery or western blot for confirmation, and finally validated using cellular degradation assays.

The comparative analysis presented in this guide elucidates the sophisticated molecular logic cells employ to control protein stability through phosphodegrons. The canonical sequential model, exemplified by FBXW7, provides a straightforward, kinase-dependent trigger for degradation. In contrast, phospho-inhibited degrons and electrostatic modulation by basic residues demonstrate the nuanced, fine-tuning capabilities of this regulatory system. The experimental data and detailed protocols provided, such as the innovative PTMe pull-down assay, offer a roadmap for researchers to systematically investigate these mechanisms in their systems of interest.

Understanding these interactions is not merely an academic exercise. The frequent dysregulation of phosphodegron pathways in cancer and other diseases highlights their profound therapeutic potential. For drug development professionals, components of these pathways—from the upstream kinases that "write" the phosphodegron signal to the E3 ligases that "read" it—represent promising targets for novel therapies, including molecular glues and PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) that aim to hijack the ubiquitin-proteasome system for targeted protein degradation.

Crosstalk between different types of post-translational modifications (PTMs), particularly ubiquitination and phosphorylation, represents a fundamental regulatory layer in eukaryotic cell signaling. This interplay functions as a sophisticated combinatorial logic system that enables cells to process complex information and generate diverse functional outcomes [7] [1]. Rather than operating in isolation, these modification systems engage in intricate cross-regulation that expands the coding potential of the proteome beyond what either PTM could achieve alone. The systems-level properties emerging from this crosstalk—including bistability, oscillations, and precise signal specificity—enable critical cell fate decisions, govern metabolic transitions, and ensure robust homeostatic control [1] [24] [25].

Understanding how ubiquitination-phosphorylation crosstalk generates these sophisticated systems behaviors provides not only fundamental biological insights but also opens new therapeutic avenues. The development of targeted protein degradation technologies, particularly PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras), exemplifies how mechanistic understanding of ubiquitination machinery can be harnessed for therapeutic intervention [26]. This review synthesizes experimental and computational evidence demonstrating how ubiquitination-phosphorylation crosstalk creates specific systems-level dynamics, with direct implications for drug development and disease treatment.

Quantitative Landscapes of Phosphorylation-Ubiquitination Crosstalk

Global proteomic studies have revealed the extensive co-occurrence of phosphorylation and ubiquitination modifications on cellular proteins. A landmark study in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identified 466 proteins with 2,100 phosphorylation sites co-occurring with 2,189 ubiquitylation sites, demonstrating the remarkable prevalence of this form of crosstalk [7]. The methodological innovation enabling this discovery—sequential enrichment strategies for co-modified proteins—provided the first systematic view of this combinatorial PTM landscape.

Table 1: Global Analysis of Phosphorylation-Ubiquitination Crosstalk in Yeast

| Analytical Method | Ubiquitylated Proteins Identified | Proteins with Both PTMs | Ubiquitylation Sites | Phosphorylation Sites on Co-modified Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ub-protein Enrichment | 891 | 321 | 2,395 | 1,769 |

| SCX-IP | 1,817 | 245 | 4,659 | 437 |

| Total | 1,920 | 466 | 5,629 | 2,100 |

Evolutionary analysis of these co-modification sites revealed striking functional significance. Phosphorylation sites found co-occurring with ubiquitination demonstrated significantly higher conservation than the entire set of phosphorylation sites, suggesting they represent functionally important regulatory nodes under strong selective pressure [7]. This conservation pattern was specific to phosphorylation sites, as ubiquitylation sites on phosphoproteins showed similar conservation levels regardless of phosphorylation status.

The functional domains enriched in ubiquitylated phosphoproteins provide insights into the biological processes most heavily regulated by this crosstalk. Ribosomal proteins, membrane transporters, arrestin domains, and proteins localized to the cell bud showed significant enrichment, pointing to critical roles in protein translation, transmembrane transport, and cell polarity [7].

Systems-Level Dynamics: Bistability and Oscillations

Theoretical Foundations of Bistability

Bistability represents a fundamental systems property where biological networks can exist in two distinct stable states, enabling digital decision-making processes such as cell fate determination. While positive feedback loops have traditionally been considered essential for bistability, recent research demonstrates that multisite phosphorylation alone can generate bistable responses without explicit feedback regulation [25].

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, an essential eukaryotic signaling pathway governing proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death, exemplifies this principle. Kholodenko and colleagues established that a single level of the MAPK cascade, involving dual phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycles, can theoretically exhibit hysteresis and bistability based solely on the intrinsic properties of the pathway architecture [25]. This finding fundamentally altered our understanding of how bistability can emerge from seemingly straightforward biochemical systems.

Metabolic Oscillations Between Growth and Quiescence

The "push-pull" bistability model explains how cells oscillate between quiescent and growth/proliferation states based on the availability of a central metabolic resource [24]. In yeast metabolic cycles (YMCs), synchronized populations exhibit oscillations in oxygen consumption that tightly correlate with distinct physiological states. During high-oxygen-consumption phases, cells activate biosynthetic and growth programs, while low-oxygen-consumption phases are characterized by autophagy, vacuolar function, and quiescence markers [24].

Table 2: Characteristics of Growth-Quiescence Oscillation States in Yeast

| Parameter | Growth/Proliferation State | Quiescent State |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Consumption | High | Low |

| Gene Expression | Biosynthesis and growth programs | Autophagy and vacuolar function |

| Metabolic Processes | Anabolic | Catabolic |

| Cell Division | Synchronous division during specific temporal window | Non-dividing |

| Hallmark Features | Commitment to cell cycle progression | Reversibly nondividing state |

This frustrated bistability model requires tripartite communication between the metabolic resource determining oscillations and the quiescent and growth state cells. Cells in each state exhibit hysteresis (memory) of their current state and actively "push-pull" cells from the other state, creating a robust oscillatory system [24]. The identification of specific central metabolites controlling these transitions remains an active research area with profound implications for understanding cellular metabolism in both normal physiology and disease states such as cancer.

Diagram 1: Push-pull bistability model governing growth-quiescence transitions. Metabolic resource availability drives state switching, with each state reinforcing itself and antagonizing the alternative state.

Molecular Mechanisms of Phosphorylation-Ubiquitination Crosstalk

Phosphodegrons and Coordinated Protein Degradation

Perhaps the best-characterized molecular mechanism of phosphorylation-ubiquitination crosstalk is the phosphodegron—a specific phosphorylation pattern that functions in cis to promote subsequent ubiquitylation of a substrate [7]. Phosphodegrons provide temporal control of protein degradation, imparting irreversibility and robustness to critical cellular processes such as cell cycle progression. The identification of 466 co-modified proteins in yeast suggests that phosphodegrons represent a widespread regulatory mechanism rather than a specialized pathway [7].

Beyond substrate recognition, phosphorylation also directly regulates the activity of E3 ubiquitin ligases themselves. The Cbl family of E3 ligases, crucial regulators of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) endocytosis, undergoes phosphorylation-induced conformational changes that activate their ubiquitin ligase function [1]. Following EGFR activation and autophosphorylation, Cbl binds to phosphotyrosine residues on the receptor, leading to phosphorylation of a critical tyrosine residue (Y371 in c-Cbl) that enables full rotation of the Cbl linker region. This structural rearrangement exposes the RING domain, allowing E2 binding and stimulating Cbl E3 ligase activity [1].

Reciprocal Regulation and Feedback Loops

The crosstalk between phosphorylation and ubiquitination is notably reciprocal, with ubiquitination events regulating kinase activity and phosphorylation modulating ubiquitin ligase function. This bidirectional regulation creates complex feedback and feedforward loops that enable sophisticated signal processing capabilities [1].

In the EGFR/MAPK pathway, ubiquitination provides crucial negative feedback regulation that shapes both the amplitude and duration of signaling. Cbl-mediated ubiquitination of activated EGFR promotes its endocytosis and subsequent lysosomal degradation, effectively terminating signaling [1]. Additionally, deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) such as USP8 can reverse this process, providing another layer of regulation. USP8 itself is regulated by phosphorylation, creating an integrated control system where phosphorylation regulates ubiquitination, which in turn controls receptor trafficking and signaling output [1].

Diagram 2: Phosphorylation-ubiquitination crosstalk in EGFR endocytosis. EGFR autophosphorylation recruits Cbl E3 ligase, leading to receptor ubiquitination and subsequent endocytic sorting for degradation.

Signal Specificity Through Crosstalk and Insulation

The Specificity and Fidelity Problems in Signaling Networks

In complex signaling networks with multiple parallel pathways, maintaining signal specificity presents a fundamental challenge. The problems of "signal fidelity" (a pathway's capacity to prevent activation of its target by non-cognate signals) and "signal specificity" (a pathway's ability to avoid activating non-targets with its own signal) become particularly acute when pathways share components [27]. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses have revealed extensive crosstalk between cell-cell communication pathways, with shared signaling components creating potential interference between signaling channels [27].

Computational methods like SigXTalk leverage hypergraph learning frameworks to quantify pathway fidelity and specificity from single-cell RNA-seq data. This approach encodes higher-order relations among receptors, transcription factors, and target genes within regulatory pathways, allowing systematic analysis of how crosstalk affects signal specificity [27]. By measuring the relative regulatory strength of pathways within crosstalk modules, researchers can identify key shared molecules and their roles in transferring shared signaling information.

Insulating Mechanisms and Combinatorial Control

Cells employ multiple strategies to prevent inappropriate crosstalk and maintain signaling specificity. Spatial compartmentalization represents a powerful insulating mechanism, separating potentially interfering pathways into distinct cellular locations [28]. Additionally, the formation of specific multi-protein complexes creates functional insulation by bringing together dedicated signaling components while excluding others [28].

Combinatorial control represents another key strategy for maintaining specificity. The simultaneous requirement for multiple input signals to activate a pathway reduces the likelihood of accidental activation. In ubiquitination-phosphorylation crosstalk, this often manifests as requirements for specific phosphorylation patterns (rather than single phosphorylation events) to trigger ubiquitination, or the need for multiple ubiquitination events to regulate kinase activity [1]. This combinatorial logic significantly expands the coding capacity of the signaling system while maintaining specificity.

Research Reagent Solutions for Studying PTM Crosstalk

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Analyzing Ubiquitination-Phosphorylation Crosstalk

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| His-tagged Ubiquitin | Enrichment of ubiquitylated proteins | Enables cobalt-NTA affinity purification of modified proteins [7] |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Immunoenrichment of phosphopeptides | Isolation of phosphorylated peptides for MS analysis [7] |

| diGly Antibody | Identification of ubiquitylation sites | Recognizes Gly-Gly remnant on modified lysines after tryptic digestion [7] |

| SCX Chromatography | Separation of charged peptides | Enriches for both ubiquitylated peptides and ubiquitylated phosphopeptides [7] |

| SigXTalk Algorithm | Computational crosstalk analysis | Hypergraph learning to quantify pathway fidelity and specificity from scRNA-seq [27] |

| PROTAC Molecules | Targeted protein degradation study | Heterobifunctional molecules recruiting E3 ligases to target proteins [26] |

Experimental Workflows for Global PTM Crosstalk Analysis

The systematic identification of proteins co-modified by phosphorylation and ubiquitination requires sophisticated sequential enrichment strategies. Two complementary methodological approaches have been developed to address the challenges of identifying these typically low-stoichiometry modifications [7].

The first approach employs protein-level enrichment using cobalt-NTA affinity purification to isolate His-tagged ubiquitin-modified proteins. Following digestion, phosphopeptides are enriched from both the ubiquitin-enriched and ubiquitin-depleted fractions, allowing identification of phosphorylation sites specific to ubiquitylated protein isoforms. Additionally, diGly antibody-based enrichment identifies specific ubiquitylation sites in the ubiquitin-enriched population [7].

The second approach utilizes peptide-level sequential enrichment through strong-cation exchange (SCX) chromatography to separate peptides by solution charge, followed by diGly antibody enrichment of ubiquitylated peptides from all SCX fractions. This method specifically identifies peptides concurrently modified by both phosphorylation and ubiquitylation, establishing that both modifications are present on the same protein isoform, though it is limited to modifications in close sequence proximity [7].

Diagram 3: Experimental workflow for identifying co-modified proteins. Sequential enrichment strategies enable identification of phosphorylation and ubiquitination sites on the same protein molecules.

Therapeutic Applications and Future Perspectives

The mechanistic understanding of ubiquitination-phosphorylation crosstalk has enabled groundbreaking therapeutic approaches, particularly in targeted protein degradation. PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) represent the most advanced application, utilizing heterobifunctional molecules to recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases to specific target proteins, leading to their degradation [26]. The field has expanded beyond the initial focus on CRBN and VHL ligases to include other therapeutically relevant E3 ligases such as MDM2, which exhibits dual functionality as both a regulator of p53 and an E3 ligase capable of being harnessed for targeted degradation [26].

The expansion of E3 ligases available for PROTAC design has significantly broadened the scope of targetable proteins. Current databases include 6,111 PROTACs targeting 442 distinct protein targets through 20 different E3 ligases [26]. Key targets such as the androgen receptor (AR), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutants, and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) have been the focus of extensive PROTAC development efforts, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of manipulating ubiquitination machinery.

Future research directions will likely focus on expanding the repertoire of E3 ligases suitable for therapeutic applications, developing selective ligands for previously untargetable proteins, and exploiting the oscillatory and bistable behaviors generated by PTM crosstalk for chronotherapeutic applications. The integration of computational and experimental approaches will be essential for mapping the complex dynamics of these post-translational regulatory networks and harnessing their therapeutic potential.

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) represent a crucial regulatory layer in cellular signaling, controlling protein function, localization, and stability. While phosphorylation and ubiquitination have established a well-characterized crosstalk paradigm, the network of interactions involving the Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) pathway with acetylation and other PTMs is rapidly emerging as an equally complex and biologically significant area of research. This expansion of the crosstalk network enables cells to implement complex signaling processing modules that function as logical gates in cellular networks, integrating signals from multiple sources to fine-tune biological responses [29] [30]. SUMOylation, the reversible covalent attachment of SUMO proteins to target substrates, regulates diverse cellular processes including transcription, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and signal transduction [31]. The dynamic interplay between SUMOylation and other PTMs, particularly acetylation, creates sophisticated regulatory circuits that control key cellular functions, with important implications for disease mechanisms and therapeutic development.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major PTMs in Signaling Crosstalk

| PTM Type | Enzymes Involved | Target Residues | Primary Functions | Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUMOylation | E1 (SAE1/SAE2), E2 (Ubc9), E3 (PIAS, RanBP2), SENPs | Lysine (consensus ψKxE/D) | Transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, protein localization | Cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, autoimmune disorders [31] |

| Acetylation | HATs (p300/CBP), HDACs | Lysine | Chromatin remodeling, transcription activation, metabolic regulation | Cancer, leukemia, neurological disorders [32] |

| Phosphorylation | Kinases, Phosphatases | Serine, Threonine, Tyrosine | Signal transduction, enzyme activation, cell cycle control | Cancer, inflammatory diseases, metabolic disorders [30] [32] |

| Ubiquitination | E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascade, DUBs | Lysine | Protein degradation, endocytosis, DNA repair | Cancer, muscle wasting, viral infection [30] [32] |

Molecular Mechanisms of SUMOylation and Its Crosstalk

The SUMOylation Machinery

SUMOylation involves a well-defined enzymatic cascade that conjugates SUMO proteins to specific lysine residues on target proteins. The process begins with SUMO maturation, where newly synthesized SUMO is cleaved by SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs) to expose a C-terminal diglycine motif. The mature SUMO is then activated in an ATP-dependent manner by the heterodimeric E1 enzyme SAE1/SAE2, transferred to the E2 conjugating enzyme Ubc9, and finally ligated to target proteins with the assistance of E3 ligases such as PIAS family members, RanBP2, and Pc2 [31]. This dynamic modification is reversed through deSUMOylation catalyzed by SENPs, creating a reversible regulatory switch. Mammals express multiple SUMO paralogs (SUMO1-5) with distinct functions and cellular distributions, adding further complexity to this system [31]. SUMOylation can manifest as mono-SUMOylation, multi-SUMOylation (multiple acceptor sites), or poly-SUMOylation (SUMO chains), with SUMO2/3 being primarily responsible for chain formation due to internal consensus sequences [31].

SUMOylation-Acetylation Crosstalk: Molecular Switches and Antagonistic Regulation

The crosstalk between SUMOylation and acetylation represents a sophisticated regulatory mechanism that fine-tunes protein function, particularly for transcription factors and chromatin-associated proteins. Research has revealed that these modifications can engage in both competitive and sequential interactions on the same protein substrates, creating molecular switches that integrate diverse cellular signals.

A paradigm for this crosstalk has been established through studies on p53, where sumoylation at lysine 386 blocks subsequent acetylation by p300, while p300-acetylated p53 remains permissive for ensuing sumoylation [33]. This hierarchical modification directly impacts p53 function, as sumoylation prevents DNA binding, thereby inhibiting transcriptional activation of target genes. Importantly, acetylation can restore the DNA-binding activity of sumoylated p53, demonstrating how this antagonistic relationship creates a dynamic regulatory switch [33]. This switch-like behavior allows cells to rapidly respond to different stimuli by toggling between activating and repressive modifications on a key tumor suppressor.

Beyond direct competition on transcription factors, acetylation can directly regulate the SUMO machinery itself. SUMO proteins undergo acetylation at specific lysine residues (K37 in SUMO1 and K33 in SUMO2) within their basic interface, neutralizing positive charges and preventing interaction with SUMO-interaction motifs (SIMs) in proteins like PML, Daxx, and PIAS family members [34]. This acetyl-dependent switch expands the regulatory repertoire of SUMO signaling by determining the selectivity and dynamics of SUMO-SIM interactions, thereby affecting processes such as PML nuclear body assembly and SUMO-mediated gene silencing [34].

The reverse regulatory direction also occurs, where SUMOylation controls acetylation-dependent processes. The histone reader TRIM24 exemplifies this bidirectional crosstalk, as its binding to acetylated chromatin (H3K4me0/K23ac) via its tandem PHD-bromodomain induces TRIM24 SUMOylation at lysine residues 723 and 741 [35]. Inhibition of histone deacetylation increases TRIM24's interaction with chromatin and its subsequent SUMOylation, establishing a functional connection between histone acetylation and reader protein SUMOylation that regulates oncogenic functions in breast cancer [35].

Figure 1: SUMOylation-Acetylation Crosstalk on p53. Sumoylation at K386 inhibits DNA binding, while acetylation at K373/K382 permits or restores DNA binding capability, creating a molecular switch that regulates p53 transcriptional activity [33].

SUMOylation-Phosphorylation Interplay: Coordinated Regulation

The coordination between SUMOylation and phosphorylation represents another crucial axis in the PTM crosstalk network. These modifications can function sequentially, synergistically, or antagonistically to control protein activity, stability, and interactions. A key mechanism underlying this coordination is the presence of phosphorylation-dependent SUMOylation motifs (PDSMs), which contain a SUMO consensus site adjacent to a proline-directed phosphorylation site (ψ-K-X-D/E-X-X-S-P) [31]. This structural arrangement allows phosphorylation at the serine residue to enhance SUMOylation at the nearby lysine, creating a phospho-switch that integrates kinase signaling with the SUMO pathway.

The interplay between SUMOylation and phosphorylation also extends to their functional outcomes. For instance, SUMOylation can inhibit tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5, converting it from an active to inactive state and thereby modulating signaling transduction [31]. Additionally, the kinase CK2 phosphorylates serine or threonine residues adjacent to the hydrophobic core of SIMs in proteins like PML and PIAS family members, enhancing their binding to SUMO through electrostatic interactions with basic residues in the SUMO interface [34]. This phosphorylation-dependent enhancement of SUMO binding affects processes such as PML nuclear body dynamics and SUMO-mediated transcriptional regulation.

SUMOylation-Ubiquitination Crosstalk: From Degradation to Stability

SUMOylation and ubiquitination share structural similarities as ubiquitin-like modifiers but often exert opposing effects on protein stability. While ubiquitination typically targets proteins for proteasomal degradation, SUMOylation can counteract this fate or even promote stability under specific contexts. This antagonistic relationship is exemplified by IκBα, where SUMOylation at lysine 21 provides protection against ubiquitin-mediated degradation, thereby modulating NF-κB signaling [31]. Furthermore, phosphorylation of IκBα at serines 32 and 36 inhibits SUMOylation, creating a complex tripartite crosstalk that integrates multiple signaling inputs [31].

Beyond simple antagonism, SUMOylation and ubiquitination can also function cooperatively through sequential modifications. Poly-SUMO chains can serve as platforms for recruitment of SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs), which subsequently ubiquitinate the substrate and target it for proteasomal degradation [31]. This SUMO-dependent ubiquitination creates a fail-safe mechanism for eliminating persistently sumoylated proteins and has been implicated in quality control pathways. Advanced proteomic studies have revealed extensive crosstalk between these pathways, with co-regulation observed on deubiquitinase enzymes and SUMOylation of proteasome subunits affecting their recruitment to subnuclear compartments like PML nuclear bodies [36].

Table 2: Experimental Evidence of SUMOylation Crosstalk with Other PTMs

| Crosstalk Type | Experimental System | Key Findings | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUMO-Acetylation | In vitro sumoylation system with p53; Cell-based assays [33] | Sumoylation at K386 blocks acetylation by p300; Acetylation restores DNA binding of sumoylated p53 | Fine-tuning of p53 transcriptional activity |

| SUMO-Acetylation | Site-specific acetylation of SUMO paralogs; Biochemical binding assays [34] | Acetylation of SUMO1-K37/SUMO2-K33 prevents binding to SIMs in PML, Daxx, PIAS | Altered PML nuclear body dynamics; Attenuated gene silencing |

| SUMO-Phosphorylation | STAT5 modification studies; CK2 phosphorylation assays [34] [31] | SUMOylation inhibits STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation; CK2 phosphorylates SIMs to enhance SUMO binding | Modulation of signaling transduction; Enhanced SUMO-SIM interactions |

| SUMO-Ubiquitination | Sequential peptide immunopurification; Proteomic analysis [36] | Co-regulation on deubiquitinase enzymes; SUMOylation of proteasome subunits | Recruitment of proteasome to PML nuclear bodies; Regulation of protein degradation |

Methodological Approaches for Studying PTM Crosstalk

Proteomic Technologies for System-Level Analysis

Advances in mass spectrometry-based proteomics have revolutionized the study of PTM crosstalk by enabling the identification and quantification of thousands of modification sites across the proteome. The development of sequential peptide immunopurification represents a significant methodological innovation, allowing researchers to study both SUMOylation and ubiquitylation from a single biological sample [36]. This approach involves the stable expression of a 6xHis-SUMO3-Q87R/Q88N mutant in HEK293 cells, enrichment of SUMOylated proteins on NiNTA columns, followed by on-bead digestion and immunopurification of SUMO-modified peptides using specific antibodies. Optimization of this method through antibody cross-linking to magnetic beads and refined incubation buffers has achieved remarkable enrichment levels of 62.9%, facilitating the identification of over 10,000 SUMO sites in human cells [36].

Quantitative proteomic analyses using this methodology have revealed dynamic changes in the SUMOylome and ubiquitinome in response to proteasome inhibition, uncovering extensive crosstalk between these modifications in pathways controlling protein degradation. The application of high-sensitivity MS methods with optimized automatic gain control settings and extended injection times has further enhanced the depth of coverage, enabling more comprehensive mapping of the PTM crosstalk network [36]. These technological advances provide unprecedented opportunities to study SUMOylation crosstalk at a systems level, moving beyond candidate-based approaches to discover novel regulatory nodes in the PTM network.

Computational Prediction of PTM Crosstalk

The growing complexity of PTM interactions has spurred the development of computational approaches to predict and prioritize crosstalk events for experimental validation. Recent innovations include WPTCMN/PTCMN, a unified model based on a Multilayer Network structure that simultaneously predicts both intra-protein and inter-protein PTM crosstalk [37]. This integrated deep neural network incorporates evolutionary, structural, and dynamic features of proteins, using random walks to dynamically learn single-layer network features, multilayer network correlation features, and node features within the PTM crosstalk network [37].

These computational approaches address the challenges of limited and imbalanced datasets in PTM crosstalk research, providing valuable insights and guidance for future experimental investigations. The PTMcode web resource represents another valuable tool, compiling approximately 200 manually validated examples of intra-protein PTM crosstalk in the human proteome among ten selected PTM types, while predicting many more potential interactions based on same residue competition, structural proximity, and coevolution [29]. These computational resources complement experimental methods by enabling hypothesis generation and prioritization of functionally relevant crosstalk events for mechanistic validation.

Figure 2: Workflow for Sequential Analysis of SUMOylation and Ubiquitination. This optimized immunoaffinity method enables the study of both modifications from a single sample, facilitating the identification of crosstalk events [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SUMOylation Crosstalk Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUMO Mutants | 6xHis-SUMO3-Q87R/Q88N; SUMO2 T91R; ZNF451 tag [36] [38] | Facilitates identification of SUMO sites; induces targeted SUMOylation | Proteomic studies; Functional validation of SUMOylation effects |

| Enzymes & Inhibitors | Proteasome inhibitor MG132; HDAC inhibitors; p300/CBP inhibitors [33] [36] | Modifies PTM pathways; reveals crosstalk dynamics | Perturbation studies to interrogate functional relationships between PTMs |

| Specific Antibodies | Anti-K-(NQTGG); Anti-di-glycine; Anti-acetyllysine; Phospho-specific antibodies [36] | Enrichment and detection of specific PTMs; Immunofluorescence | Immunopurification; Western blotting; Cellular localization studies |

| Expression Systems | HEK293-SUMO3m stable cell line; Site-specific acetylation system [34] [36] | Production of homogenously modified proteins; Controlled PTM expression | Biochemical studies; Functional characterization of specific modifications |

| Computational Tools | WPTCMN/PTCMN; PTMcode; PTM-X [29] [37] | Prediction of PTM crosstalk; Database of known interactions | Hypothesis generation; Prioritization of crosstalk events for validation |

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

The intricate crosstalk between SUMOylation and other PTMs has significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies. Aberrant SUMOylation has been implicated in various pathological conditions, including cancers, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune diseases [31]. In cancer, the SUMO pathway contributes to malignant transformation through multiple mechanisms, including the regulation of oncogenes and tumor suppressors like p53 [33]. The discovery of crosstalk between histone acetylation and TRIM24 SUMOylation in breast cancer highlights how integrated PTM networks can drive oncogenic processes, suggesting novel therapeutic targets [35].

The therapeutic potential of targeting SUMOylation crosstalk is increasingly recognized, though this field remains relatively immature compared to kinase-targeted therapies. Current strategies include developing inhibitors of SUMO conjugation or deconjugation, as well as approaches to disrupt specific SUMO-SIM interactions [34]. The development of small-molecule inhibitors of the TRIM24 bromodomain (IACS-9571) that disrupt its association with chromatin and subsequent SUMOylation demonstrates the feasibility of targeting reader domains within the PTM crosstalk network [35]. As our understanding of SUMOylation crosstalk deepens, opportunities will emerge to develop more precise therapeutic interventions that modulate specific nodes within these complex regulatory networks rather than broadly inhibiting entire pathways.