Ubiquitination Patterns as Stage-Specific Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets in Cancer

This article synthesizes the latest evidence establishing a direct correlation between dynamic ubiquitination patterns and cancer stage and grade.

Ubiquitination Patterns as Stage-Specific Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets in Cancer

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest evidence establishing a direct correlation between dynamic ubiquitination patterns and cancer stage and grade. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational role of ubiquitinome alterations in tumorigenesis, detail advanced methodologies for profiling these changes, and analyze their clinical applications. The content covers the development of ubiquitination-based prognostic models, discusses challenges in therapeutic targeting of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, and validates these findings through multi-omics integration and clinical trial data. The review underscores the immense potential of ubiquitinomics in advancing predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine (PPPM) in oncology.

Decoding the Ubiquitinome: How Ubiquitination Patterns Define Cancer Progression and Staging

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) serves as the primary pathway for controlled intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, functioning as a critical mechanism for maintaining cellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis) [1]. This sophisticated system ensures the precise elimination of damaged, misfolded, or short-lived regulatory proteins through an ATP-dependent process [2]. The UPS represents a highly selective degradation machinery that governs the turnover of approximately 80-90% of intracellular proteins, distinguishing it from the autophagy-lysosome pathway which primarily handles bulk degradation [3]. The clinical importance of the UPS is well-established in oncology, particularly in multiple myeloma, where proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib have become first-line therapeutics, validating the UPS as a viable drug target [1] [4].

Beyond its housekeeping functions, the UPS plays indispensable roles in regulating vital cellular processes including cell cycle progression, signal transduction, gene expression, apoptosis, and immune responses [1] [2]. The system's operation involves a coordinated enzymatic cascade that tags target proteins with ubiquitin molecules, marking them for recognition and degradation by the 26S proteasome complex [1]. Understanding the intricate mechanisms of ubiquitination and the proteasome is fundamental to cancer biology, as dysregulation of UPS components contributes significantly to tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance across various cancer types [1] [5].

Table 1: Core Components of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Component | Number in Humans | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin | 1 gene (multiple copies) | Protein tag for degradation | 76-amino acid, highly conserved heat-resistant protein [1] |

| E1 Enzymes | ~2 | Ubiquitin activation | ATP-dependent, forms thioester bond with ubiquitin [1] [6] |

| E2 Enzymes | ~40 | Ubiquitin conjugation | Transfers ubiquitin from E1 to E3/substrate [6] |

| E3 Ligases | 500-1000 | Substrate recognition | Determines specificity, recognizes degradation signals [2] |

| 26S Proteasome | Multiple complexes | Protein degradation | 2.5 MDa complex with 20S core and 19S regulatory particles [2] |

| DUBs | ~100 | Deubiquitination | Cleaves ubiquitin chains, provides reversibility [7] [4] |

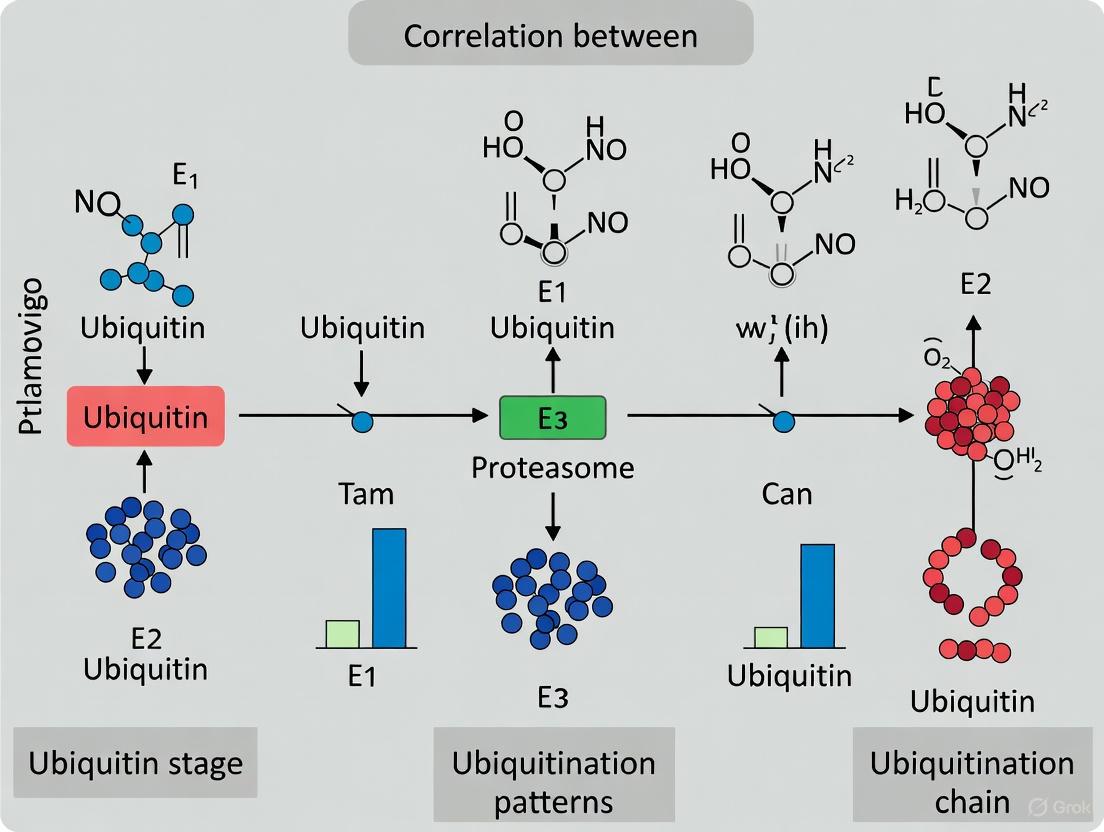

The Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

The process of ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade that conjugates ubiquitin molecules to specific substrate proteins, thereby marking them for proteasomal degradation. This cascade requires the coordinated action of three distinct enzyme classes: E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme), and E3 (ubiquitin ligase) [1] [2].

Mechanism of Ubiquitin Transfer

The ubiquitination cascade begins with ubiquitin activation by E1 enzymes through an ATP-dependent reaction. During this initial step, E1 forms a high-energy thioester bond between its active-site cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine (Gly76) of ubiquitin [1] [4]. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the cysteine active site of an E2 conjugating enzyme through a transesterification reaction [1]. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2 enzymes, each containing a highly conserved catalytic UBC (Ubiquitin-Conjugating) domain [6].

The final step involves E3 ubiquitin ligases, which number between 500-1000 in humans and provide substrate specificity to the system [2]. E3 enzymes facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein, forming an isopeptide bond between the C-terminus of ubiquitin and the ε-amino group of the substrate lysine [1]. Some E3 ligases directly catalyze ubiquitin transfer, while others act as scaffolds that bring the E2~ubiquitin complex into proximity with the substrate [6]. This enzymatic cascade can be repeated to attach additional ubiquitin molecules to previously conjugated ubiquitin moieties, forming polyubiquitin chains with diverse topologies [2].

Diagram 1: The ubiquitination enzymatic cascade showing sequential E1-E2-E3 action.

Experimental Analysis of Ubiquitination

Investigating the ubiquitination cascade requires specific methodological approaches that can capture these dynamic enzyme-substrate interactions. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays serve as a fundamental technique for validating physical interactions between UPS components. For example, the interaction between UCHL1 (a deubiquitinating enzyme) and CIP2A (an oncoprotein) in gastric cancer was confirmed through endogenous immunoprecipitation assays using anti-CIP2A antibodies, followed by Western blot analysis to detect UCHL1 [7].

Western blotting under denaturing conditions can detect protein ubiquitination by observing characteristic molecular weight shifts, though this approach may not distinguish between mono- and polyubiquitination. More sophisticated methods include in vitro ubiquitination assays that reconstitute the cascade using purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ubiquitin, and ATP, allowing researchers to demonstrate direct ubiquitination of substrate proteins [6]. For studying E2 enzymes specifically, covalent inhibitors like NSC697923 that target the catalytic cysteine (Cys85) in UBE2N can be employed to interrogate specific E2 functions, though these inhibitors typically cause loss of function rather than facilitating degradation [6].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Studying Ubiquitination

| Method | Application | Key Steps | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-immunoprecipitation | Protein-protein interactions | Cell lysis, antibody incubation, precipitation, Western blot | Detection of interacting partners [7] |

| Western Blot | Protein expression/ modification | SDS-PAGE, transfer, antibody probing, detection | Molecular weight shifts, expression levels [7] [8] |

| In vitro Ubiquitination Assay | Direct ubiquitination confirmation | Purified E1/E2/E3, ubiquitin, ATP incubation | Ubiquitinated substrates on Western blot [6] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Ubiquitin chain topology | Protein digestion, LC-MS/MS, data analysis | Identification of linkage types [9] |

| Genetic Knockdown/ Knockout | Functional validation | siRNA/shRNA/CRISPR, phenotypic assays | Changes in proliferation, migration, invasion [7] |

Ubiquitin Chain Topologies and the Ubiquitin Code

Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can serve as attachment points for subsequent ubiquitin molecules, enabling the formation of polyubiquitin chains with diverse structures and functions [2]. The specific arrangement of these ubiquitin chains creates a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that determines the fate of modified proteins [9].

Structural and Functional Diversity of Ubiquitin Chains

The topology of ubiquitin chains directly influences their biological functions. K48-linked polyubiquitin chains represent the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation and serve as the primary topology for marking proteins for destruction [2] [3]. Similarly, K11-linked chains have also been strongly associated with targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation, particularly during cell cycle regulation [9] [3]. In contrast, K63-linked polyubiquitin chains typically function as non-proteolytic signals that regulate various cellular processes including protein trafficking, DNA repair, and kinase activation [2]. These chains also target damaged organelles for clearance via the autophagy-lysosome pathway [3].

Linear ubiquitin chains (linked through M1) play critical roles in immune signaling pathways, particularly in NF-κB activation, where the LUBAC complex (Linear Ubiquitin Chain Assembly Complex) generates these atypical chains to modulate inflammatory responses [2] [4]. Other linkage types, including K27, K29, and K33, participate in various signaling functions, though their roles are less well-characterized [2]. Additionally, mixed or branched chains that incorporate multiple linkage types within a single ubiquitin polymer add further complexity to the ubiquitin code, creating an extensive repertoire of regulatory signals [9].

Diagram 2: Diverse ubiquitin chain topologies and their primary cellular functions.

Analytical Techniques for Ubiquitin Chain Characterization

Deciphering the ubiquitin code requires specialized methodologies that can distinguish between different chain topologies. Mass spectrometry-based approaches have become indispensable for comprehensive ubiquitin chain analysis, particularly tandem mass tagging (TMT) and LC-MS/MS techniques that can identify specific linkage types through characteristic peptide fragments [6]. These proteomic methods enable researchers to map ubiquitination sites and determine chain topology in complex biological samples.

Linkage-specific antibodies that recognize particular ubiquitin chain types provide an accessible alternative for initial screening experiments. These reagents can be employed in Western blotting or immunofluorescence applications to monitor changes in specific ubiquitin signals under different experimental conditions. For functional validation, enzymatic probes including linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs) can be utilized to selectively cleave particular chain types, thereby confirming their presence and importance for specific cellular processes [9].

Recent advances in chemical biology tools have further expanded the methodological toolbox for ubiquitin research. Activity-based probes that covalently label active-site cysteines in E2 enzymes or DUBs can help profile the enzymatic machinery responsible for generating or editing specific ubiquitin chain types [6]. Additionally, di-glycine remnant antibodies that recognize the characteristic signature left after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins enable proteome-wide identification of ubiquitination sites, though they cannot distinguish between chain topologies [6].

Table 3: Ubiquitin Chain Topologies and Their Functions

| Chain Type | Primary Function | Associated Processes | Key Regulatory Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation | Protein turnover, cell cycle | Most E3 ligases [2] [3] |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation | ERAD, cell cycle | APC/C, UBE2S [9] [3] |

| K63-linked | Signaling, autophagy | DNA repair, inflammation, endocytosis | TRAF6, UBE2N/UBC13 [2] [3] |

| M1-linked (Linear) | Inflammation signaling | NF-κB activation, immunity | LUBAC (HOIP, HOIL-1) [2] [4] |

| K27-linked | Signaling | Immune response, mitophagy | Unknown E3s [2] |

| K29-linked | Signaling, degradation | Proteostasis, Wnt signaling | UBE3A, UBR5 [2] [3] |

| K33-linked | Signaling | Trafficking, metabolism | Unknown E3s [2] |

| Mixed/Branched | Complex signaling | Integrated cellular responses | Multiple E2/E3 combinations [9] |

UPS Dysregulation in Cancer Biology

The ubiquitin-proteasome system plays a dual role in oncogenesis, functioning as both a tumor suppressor mechanism through the degradation of oncoproteins and as a tumor promoter when hijacked to eliminate tumor suppressor proteins [1] [5]. This delicate balance becomes disrupted in numerous cancer types, with specific UPS components demonstrating distinctive dysregulation patterns across different malignancies.

Oncogenic Alterations in UPS Components

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) frequently exhibit altered expression in cancer, with UCHL1 showing marked upregulation in approximately 70% of gastric cancer cases [7]. Elevated UCHL1 expression correlates with poor patient prognosis and promotes tumor progression through stabilization of oncogenic clients like CIP2A, which in turn enhances c-Myc signaling and drives proliferation [7]. In lung adenocarcinoma, comprehensive bioinformatics analyses have identified a ubiquitination-related risk score (URRS) based on four ubiquitination-related genes (DTL, UBE2S, CISH, and STC1) that effectively stratifies patients into distinct prognostic groups [5].

The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2T demonstrates elevated expression across multiple cancer types, including multiple myeloma, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and ovarian cancer [8]. UBE2T upregulation associates with reduced overall and progression-free survival, positioning it as a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target. Functional studies link UBE2T to key oncogenic pathways including cell cycle regulation, p53 signaling, and DNA damage response [8]. Pan-cancer analyses further identify gene amplification as the predominant genetic alteration affecting UBE2T across various malignancies [8].

Tumor-Specific UPS Signatures

The development of ubiquitination-based molecular signatures provides insights into cancer-specific UPS alterations. In lung adenocarcinoma, ubiquitination-related subtypes identified through unsupervised clustering algorithms demonstrate significant differences in tumor mutation burden (TMB) and clinical outcomes [5]. Patients classified into the high-risk URRS group exhibit not only worse prognosis but also distinct tumor microenvironment characteristics, including elevated PD-1/PD-L1 expression, increased TMB, and enhanced tumor neoantigen burden [5].

These UPS alterations directly impact therapeutic responses, as evidenced by differential sensitivity to chemotherapy agents between ubiquitination subtypes. The high URRS group shows lower IC50 values for various chemotherapeutic drugs, suggesting increased susceptibility to specific treatment modalities [5]. Additionally, UBE2T expression correlates with sensitivity to targeted agents like trametinib and selumetinib while showing negative correlations with CD-437 and mitomycin sensitivity [8]. These findings highlight the potential for UPS-based biomarkers to guide treatment selection and predict therapeutic responses.

Diagram 3: UPS component dysregulation in cancer pathogenesis.

Emerging UPS-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

The clinical validation of proteasome inhibitors for multiple myeloma treatment established the UPS as a legitimate therapeutic target, spurring the development of more precise strategies that target specific UPS components [1] [4]. These innovative approaches aim to achieve enhanced selectivity while mitigating the broader toxicity associated with general proteasome inhibition.

PROTAC Technology and Molecular Glues

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) represent a groundbreaking therapeutic modality that hijacks the UPS for targeted protein degradation [1] [9]. These heterobifunctional molecules consist of two distinct binding moieties connected by a chemical linker: one that engages the target protein of interest, and another that recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase [9]. This engineered proximity facilitates ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the target protein, effectively eliminating it from the cell.

The clinical potential of PROTACs is demonstrated by assets currently in advanced development, including ARV-110 and ARV-766 targeting the androgen receptor for prostate cancer, and ARV-471 targeting the estrogen receptor for breast cancer [9]. These degraders offer several advantages over traditional inhibitors, including event-driven catalysis (enabling efficacy at low doses), the ability to target previously "undruggable" proteins like transcription factors and scaffolding proteins, and potentially improved selectivity profiles [9]. Notably, PROTACs have demonstrated success against challenging targets including STAT3 and c-Myc, which have historically resisted conventional inhibition approaches [9].

Molecular glue degraders represent a related approach that induces novel interactions between E3 ligases and target proteins without a physical linker. The immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) like thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide exemplify this strategy, acting as molecular glues that redirect the CRL4CRBN E3 ligase to degrade specific zinc-finger transcription factors (IKZF1, IKZF3) in multiple myeloma [9]. More recently, covalent molecular glues like EN450 have been discovered that recruit NF-κB to UBE2D, expanding the potential applications of this technology [6].

Expanding the UPS Therapeutic Toolbox

Beyond PROTACs and molecular glues, emerging strategies aim to co-opt additional UPS components for therapeutic purposes. These include approaches that target E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, non-substrate receptor E3 components, E3-associated proteins, and even the proteasome itself with greater specificity than first-generation proteasome inhibitors [6]. The development of covalent E2-targeted degraders that exploit allosteric cysteines in E2 enzymes represents a particularly innovative direction that bypasses traditional E3 recruitment [6].

The efficacy of UPS-targeted therapies is influenced by various cellular parameters including target protein localization, E3 ligase expression patterns, and the activity of deubiquitinating enzymes [9]. For instance, the subcellular compartmentalization of targets significantly impacts their susceptibility to different PROTACs, with some E3 ligases (like VHL) showing superior activity against endoplasmic reticulum-localized targets, while others (like CRBN) perform better against nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins [9]. Understanding these contextual factors is essential for rational degrader design and patient stratification strategies.

Table 4: Current UPS-Targeted Therapeutic Agents in Clinical Development

| Therapeutic Class | Representative Agents | Molecular Target | Clinical Stage | Primary Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, Ixazomib | 20S proteasome core | Approved (Phase III for newer agents) | Multiple myeloma [1] |

| PROTACs | ARV-110, ARV-766 | Androgen receptor | Phase III | Prostate cancer [9] |

| PROTACs | ARV-471 | Estrogen receptor | Phase III | Breast cancer [9] |

| Molecular Glues | Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide | CRBN (IKZF1/3) | Approved | Multiple myeloma, MDS [9] |

| E1 Inhibitors | TAK-243 | UBA1 (E1 enzyme) | Phase I | Advanced solid tumors [4] |

| DUB Inhibitors | LDN-57444 | UCHL1 | Preclinical | Gastric cancer [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Investigating the ubiquitin-proteasome system requires specialized research tools that enable precise manipulation and monitoring of its components. The following table summarizes key reagents essential for UPS research, particularly in the context of cancer biology.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for UPS Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features/Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132 | Functional UPS inhibition | Reversible/irreversible proteasome blockade, apoptosis induction [1] |

| E3 Ligase Ligands | VHL ligands, CRBN ligands (thalidomide) | PROTAC development, E3 functional studies | Recruit endogenous E3 machinery for targeted degradation [9] |

| DUB Inhibitors | LDN-57444 (UCHL1 inhibitor) | DUB functional validation | Target-specific DUB inhibition, substrate stabilization studies [7] |

| E2 Inhibitors | NSC697923 (UBE2N inhibitor) | E2 enzymatic studies | Covalent inhibition of specific E2 enzymes, signaling pathway dissection [6] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage, K63-linkage specific | Ubiquitin chain topology analysis | Distinguish chain types in Western blot, immunofluorescence [2] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-based probes with warheads | DUB/E2 enzymatic activity profiling | Covalently label active enzymes, monitor functional states [6] |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | E3/DUB-specific constructs | Functional genetic screening | Targeted knockdown of UPS components, phenotypic characterization [7] |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48R, K63R, K0 (no lysines) | Ubiquitination mechanism studies | Define chain linkage requirements, dominant-negative approaches [2] |

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System represents a sophisticated regulatory network that extends far beyond simple protein disposal, encompassing complex enzymatic cascades and a diverse ubiquitin code that governs virtually all cellular processes. The intricate relationship between ubiquitin chain topologies and their specific biological functions underscores the precision of this system in maintaining cellular homeostasis. In cancer biology, UPS dysregulation emerges as a hallmark of tumorigenesis, with distinct patterns of E3 ligases, deubiquitinating enzymes, and ubiquitin chain dynamics correlating with disease progression, prognosis, and therapeutic responses. The ongoing development of UPS-targeted therapies, particularly PROTACs and molecular glues, highlights the translational potential of understanding these fundamental mechanisms. As research continues to unravel the complexities of the ubiquitin code and its alterations in disease states, the UPS promises to yield novel biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for cancer and beyond.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a sophisticated regulatory network that controls approximately 80-90% of intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, serving as a critical post-translational modification mechanism that governs protein stability, function, and localization [10] [11]. This system employs a precise enzymatic cascade comprising ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3) to tag specific substrate proteins with ubiquitin molecules, ultimately determining their fate through proteasomal degradation or functional alteration [1] [12]. The pathological significance of the UPS becomes particularly evident in oncogenesis, where dysregulation of ubiquitination processes contributes fundamentally to the acquisition of core cancer hallmarks, including sustained proliferation, evasion of growth suppressors, resistance to cell death, and activation of invasion and metastasis programs [11].

Emerging multi-cancer profiling studies have revealed that ubiquitination patterns are not static but undergo dynamic, stage-specific remodeling throughout cancer progression [13] [5]. The ubiquitinome—the complete set of ubiquitinated proteins in a cell or tissue—transforms substantially as tumors advance from early to late stages, reflecting the evolving functional requirements of cancer cells during disease progression. This review synthesizes evidence from recent pan-cancer analyses that delineate how systematic ubiquitinome reprogramming correlates with cancer stage grade, offering insights into prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic vulnerabilities that could inform stage-specific treatment strategies.

Molecular Mechanisms of Ubiquitinome Reprogramming in Cancer Progression

Ubiquitination Machinery and Chain Topology Diversity

The ubiquitination process initiates when E1 enzymes activate ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, subsequently transferring it to E2 conjugating enzymes [1] [12]. E3 ligases then catalyze the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to specific substrate proteins, with humans encoding only two E1 enzymes, approximately 50 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases that provide substrate specificity [10] [12]. This enzymatic cascade can generate diverse ubiquitin modifications, including monoubiquitination (single ubiquitin on one lysine), multi-monoubiquitination (multiple single ubiquitins on different lysines), and polyubiquitination (ubiquitin chains linked through specific lysine residues) [11].

The functional consequences of ubiquitination depend critically on the topology of ubiquitin chain linkage. K48-linked polyubiquitination primarily targets substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains typically facilitate non-proteolytic signaling processes such as DNA repair, inflammation, and protein trafficking [12] [14]. Other linkage types, including K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33, as well as linear M1-linked chains, have been associated with diverse cellular functions from DNA damage repair to metabolic regulation [12] [11]. This "ubiquitin code" complexity allows the UPS to regulate virtually all cellular processes, with distinct chain topologies becoming preferentially enriched at different cancer stages to support stage-specific biological requirements.

Stage-Specific Alterations in Ubiquitination Patterns

Multi-cancer analyses have demonstrated systematic ubiquitinome remodeling during cancer progression. In early-stage tumors, ubiquitination patterns frequently reflect attempts to maintain genomic integrity and cellular homeostasis, with enrichment of K63-linked ubiquitination supporting DNA repair mechanisms and error-free cell division [14]. As tumors advance to higher stages, the ubiquitinome shifts toward degradation of tumor suppressors and enhanced stability of oncoproteins, typically mediated through increased K48-linked ubiquitination of protective factors [13].

Advanced-stage cancers exhibit ubiquitinome signatures characterized by elevated ubiquitination of proteins involved in invasion, metastasis, and treatment resistance pathways [13] [5]. For instance, the ubiquitin-like protein UBD (also known as FAT10) demonstrates progressive overexpression across multiple cancer types, with levels correlating strongly with histological grade and clinical stage [13]. This stage-associated reprogramming creates distinct molecular vulnerabilities that may be exploited for therapeutic intervention, particularly in advanced disease states where conventional therapies often fail.

Table 1: Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Functional Roles in Cancer Progression

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Representative Roles in Cancer | Stage Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation | Degradation of tumor suppressors (p53, PTEN) | Late-stage enrichment |

| K63-linked | Signal transduction, DNA repair | NF-κB activation, DNA damage response | Early-stage maintenance |

| K11-linked | Cell cycle regulation, ERAD | Mitotic progression, quality control | Stage-dependent variation |

| K27-linked | Mitophagy, immune signaling | Mitochondrial quality control | Context-dependent |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal degradation, Wnt signaling | Alternative degradation pathway | Limited characterization |

| K33-linked | Kinase regulation, trafficking | AMPK modulation, metabolic adaptation | Emerging evidence |

| K6-linked | DNA damage repair | Fanconi anemia pathway | Damage response |

| M1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB signaling, inflammation | Immune activation, cell survival | Microenvironment interaction |

Pan-Cancer Evidence for Stage-Associated Ubiquitinome Remodeling

Systematic Ubiquitin D (UBD) Overexpression in Advanced Cancers

A comprehensive pan-cancer investigation analyzing UBD across 44 different cancer types revealed compelling evidence of stage-specific ubiquitinome alterations [13]. This study demonstrated that UBD was significantly overexpressed in 29 cancer types compared to corresponding normal tissues, with elevated expression strongly correlating with advanced histological grades and clinical stages [13]. The most prevalent genetic alteration driving UBD overexpression was gene amplification, occurring alongside epigenetic changes characterized by reduced promoter methylation in 16 cancer types [13].

Mechanistically, UBD engages key oncogenic signaling pathways—including NF-κB, Wnt, and SMAD2—and interacts with downstream effectors such as MAD2, p53, and β-catenin to promote tumor survival, proliferation, invasion, and metastatic potential [13]. Patients exhibiting UBD alterations experienced significantly reduced overall survival rates across multiple cancer types, establishing UBD as both a promising prognostic biomarker and a potential predictor of immunotherapy sensitivity [13] [15]. The consistent overexpression pattern across diverse malignancies suggests that UBD upregulation represents a convergent adaptation in advanced cancers, possibly facilitating immune evasion and metastatic progression.

Ubiquitination-Related Gene Signatures in Cancer Staging

Beyond individual ubiquitin-like proteins, systematic analyses of ubiquitination-related gene (URG) signatures have revealed distinct molecular subtypes with profound implications for cancer staging and prognosis. In lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), ubiquitination-based molecular subtyping successfully stratified patients into groups with significantly different clinical outcomes [5]. A ubiquitination-related risk score (URRS) developed from four prognostic genes (DTL, UBE2S, CISH, and STC1) demonstrated robust predictive capacity, with high-risk patients exhibiting worse prognosis, elevated PD-1/PD-L1 expression, increased tumor mutational burden, and heightened tumor neoantigen load [5].

Similarly, in breast cancer, a six-gene ubiquitination signature (ATG5, FBXL20, DTX4, BIRC3, TRIM45, and WDR78) effectively stratified patients into distinct risk categories with significant survival differences [16]. These ubiquitination-based classifiers consistently outperformed traditional clinical indicators in prognostic accuracy, highlighting the clinical utility of ubiquitinome profiling for cancer staging and outcome prediction. The reproducible performance of URGs across multiple independent validation cohorts underscores the fundamental role of ubiquitination reprogramming in driving cancer progression.

Table 2: Stage-Specific Ubiquitination Alterations Identified in Pan-Cancer Analyses

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination Alterations | Stage Correlation | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Cancers (29 types) | UBD/FAT10 overexpression | Higher histological grades and stages | Promotion of chromosomal instability, immune evasion |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | URRS signature (DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1) | Advanced stage, poor prognosis | Immune checkpoint elevation, increased TMB |

| Breast Cancer | 6-gene ubiquitination signature | High-risk disease | Altered tumor microenvironment, metabolic reprogramming |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | UBE2T-mediated H2AX monoubiquitination | Radiation resistance | Enhanced DNA damage response, CHK1 activation |

| Glioblastoma | USP14-mediated ALKBH5 stabilization | Stemness maintenance | Preservation of cancer stem cell populations |

| Colorectal Cancer | FBXW7-mediated p53 degradation | Radioresistance | Inhibition of apoptosis |

| B-cell Lymphoma | LUBAC-mediated linear ubiquitination | NF-κB activation | Enhanced survival signaling |

Analytical Frameworks for Ubiquitinome Profiling in Cancer Staging

Multi-Omics Integration for Ubiquitinome Characterization

Comprehensive ubiquitinome profiling in cancer staging employs integrated multi-omics approaches that combine genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic datasets. The analytical workflow typically begins with data acquisition from large-scale cancer genomics resources such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) projects [13]. Bioinformatics platforms including Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA2.0), cBioPortal, UALCAN, and Sangerbox then facilitate systematic analysis of ubiquitination-related gene expression, prognostic significance, promoter methylation patterns, genetic alterations, and immune infiltration associations [13] [5].

Consensus clustering algorithms applied to URG expression profiles enable identification of distinct molecular subtypes with characteristic clinical outcomes [5]. Subsequent differential expression analysis reveals URGs that are significantly altered between molecular subtypes or cancer stages. Prognostic URGs are identified through integrated application of univariate Cox regression, random survival forests, and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression algorithms, ultimately yielding ubiquitination-related risk scores that stratify patients according to clinical outcomes [5] [16].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for ubiquitinome profiling in cancer staging research.

Functional Annotation and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Following identification of stage-associated ubiquitination alterations, functional annotation elucidates the biological processes and pathways impacted by ubiquitinome remodeling. Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database facilitates construction of protein-protein interaction networks for predicted UBD-interacting proteins [13]. Subsequent Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses using platforms like DAVID reveal ubiquitination involvement in critical cancer-relevant processes including neurodegeneration, proteolysis, apoptosis, immune response, and metabolic reprogramming [13].

Advanced ubiquitinome profiling further integrates immune microenvironment assessment, examining correlations between ubiquitination patterns and immune infiltration levels, checkpoint molecule expression, microsatellite instability, tumor mutational burden, and neoantigen load [13] [5]. This comprehensive functional characterization establishes mechanistic links between ubiquitinome alterations and functional consequences across cancer stages, providing insights into how ubiquitination reprogramming drives disease progression.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitinome Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination and Cancer Staging Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Platforms | GEPIA2.0, cBioPortal, UALCAN, Sangerbox | Ubiquitination gene expression analysis, survival correlation | Integration of TCGA/GTEx data, multi-omics capability |

| Ubiquitination Databases | iUUCD 2.0, STRING | Ubiquitination-related gene compilation, interaction networks | Comprehensive URG catalogs, PPI network visualization |

| E1 Enzyme Inhibitors | MLN7243, MLN4924 | E1 enzymatic activity blockade | UPS pathway disruption, apoptosis induction |

| E2 Enzyme Inhibitors | Leucettamol A, CC0651 | E2 enzymatic function inhibition | Specific E2 targeting, mechanism studies |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | Nutlin, MI-219, PROTACs | E3 ligase substrate recruitment manipulation | Targeted protein degradation, p53 pathway activation |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, Ixazomib | 20S proteasome catalytic inhibition | Clinical application, protein stabilization |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | Compounds G5, F6 | DUB enzymatic activity suppression | Ubiquitin chain stabilization, signaling modulation |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The systematic characterization of stage-specific ubiquitinome remodeling holds profound implications for cancer diagnostics and therapeutics. Ubiquitination-based biomarkers offer promising tools for cancer staging, prognosis prediction, and treatment selection, particularly in malignancies where conventional staging systems provide limited biological insights [13] [5] [16]. The strong association between specific ubiquitination signatures and immunotherapy response suggests potential applications in predicting checkpoint inhibitor efficacy, possibly through ubiquitination-mediated regulation of PD-1/PD-L1 stability and expression [11].

From a therapeutic perspective, the stage-associated enrichment of specific ubiquitination components reveals actionable vulnerabilities for targeted intervention. Proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib have already demonstrated clinical success, particularly in multiple myeloma, establishing proof-of-concept for UPS-targeting therapies [1] [10]. Emerging strategies including proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and molecular glues represent innovative approaches to leverage the UPS for selective degradation of oncogenic proteins [17] [11]. These technologies exploit the ubiquitination machinery to target previously "undruggable" oncoproteins, with several candidates (ARV-110, ARV-471, CC-90009) advancing through clinical trials [11].

Future research directions should prioritize comprehensive mapping of ubiquitinome dynamics across the entire cancer progression continuum, from preneoplastic lesions to advanced metastatic disease. Single-cell ubiquitinome profiling technologies may reveal intratumoral heterogeneity in ubiquitination patterns and identify rare subpopulations with distinctive ubiquitination signatures driving therapy resistance [14]. The integration of ubiquitinome data with other post-translational modification networks (phosphorylation, acetylation, SUMOylation) will provide a more holistic understanding of the complex regulatory circuitry governing cancer progression [17] [14]. Ultimately, these advances promise to deliver ubiquitination-based precision oncology approaches that align therapeutic strategies with the stage-specific ubiquitinome configuration of individual tumors.

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin signaling pathway in cancer, showing key modifications and functional consequences.

Ubiquitination, a fundamental post-translational modification, has emerged as a critical regulatory mechanism in cancer progression and tumor grading. This process involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, thereby regulating their stability, activity, localization, and interactions [12] [11]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) comprises a sophisticated enzymatic cascade including ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), which work in concert to tag proteins for proteasomal degradation or functional modification [12] [18]. Beyond its well-established role in protein degradation, ubiquitination participates in nearly all cellular processes, and its dysregulation is now recognized as a hallmark of cancer pathogenesis, influencing tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis [12] [11].

Mounting evidence indicates that specific ubiquitination signatures correlate strongly with tumor grade and stage, offering unprecedented opportunities for prognostic stratification and therapeutic intervention [19] [20] [21]. The ability to decode these ubiquitination patterns provides valuable insights into the molecular drivers of cancer progression, potentially enabling more accurate patient risk assessment and personalized treatment approaches. This review synthesizes current understanding of how ubiquitination signatures reflect and influence tumor grade, with particular emphasis on key regulatory proteins, pathway interactions, and emerging methodological frameworks for clinical translation.

Molecular Mechanisms Linking Ubiquitination to Tumor Grade

The Ubiquitination Machinery in Cancer

The ubiquitination process initiates with E1 enzymes activating ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, followed by transfer to E2 conjugating enzymes, and finally, E3 ligases facilitate the attachment of ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins [12] [18]. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2 enzymes and over 600 E3 ligases, which confer substrate specificity and determine the biological outcomes of ubiquitination [12] [22]. This enzymatic cascade can generate diverse ubiquitin topologies, including monoubiquitination (single ubiquitin attachment), multimonoubiquitination (multiple single ubiquitins on different lysines), and polyubiquitination (ubiquitin chains linked through specific lysine residues) [11]. The specific linkage type determines the functional consequence for the modified protein, with K48-linked chains typically targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains more often regulate signaling transduction, DNA repair, and endocytic trafficking [12] [22].

The reverse process, deubiquitination, is catalyzed by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin moieties from substrates, thereby counteracting E3 ligase activity and providing an additional layer of regulation [12] [11]. The balanced interplay between ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating enzymes maintains cellular homeostasis, and disruption of this equilibrium frequently drives oncogenic transformation and tumor progression [11]. For instance, the deubiquitinase OTUB2 has been shown to stabilize pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) by counteracting Parkin-mediated ubiquitination, thereby enhancing glycolysis and accelerating colorectal cancer progression [11].

Ubiquitination Patterns Across Tumor Grades

Different ubiquitination signatures emerge as tumors progress from low-grade to high-grade malignancies, reflecting the evolving molecular landscape of cancer cells. High-grade tumors often exhibit upregulated ubiquitination of tumor suppressor proteins, leading to their excessive degradation, while oncoproteins may escape ubiquitin-mediated degradation through various mechanisms [12]. A pan-cancer analysis integrating data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts and five solid tumor types revealed conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures that effectively stratified patients into distinct risk categories with differential survival outcomes [19]. This study identified that ubiquitination scores positively correlated with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma, suggesting that ubiquitination patterns may underlie histological fate decisions during tumor progression [19].

Table 1: Ubiquitination Linkage Types and Their Functional Consequences in Cancer

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Role in Cancer | Associated Tumor Grades |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked chains | Proteasomal degradation | Enhanced degradation of tumor suppressors | High-grade tumors |

| K63-linked chains | Signal transduction | Activation of NF-κB, TGF-β pathways | Advanced stages with metastasis |

| K11-linked chains | Cell cycle regulation | Mitotic control, aneuploidy | High-grade proliferative tumors |

| Linear (M1) chains | NF-κB activation | Inflammation, cell survival | Therapy-resistant cancers |

| K27-linked chains | Mitochondrial autophagy | Metabolic adaptation | Nutrient-deficient tumor microenvironments |

| Monoubiquitination | DNA repair, endocytosis | DNA damage response, receptor trafficking | Varies by cancer type |

At the single-cell resolution, ubiquitination signatures enable more precise classification of distinct cell types within the tumor microenvironment and correlate with immune cell infiltration patterns, particularly macrophages, which vary significantly with tumor grade [19]. The dynamic regulation of ubiquitination across tumor grades underscores its potential as a biomarker for disease progression and therapeutic response prediction.

Prognostic Ubiquitination Signatures Across Cancer Types

Development of Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures

The establishment of ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures (URPS) represents a significant advancement in molecular cancer classification. These signatures leverage the expression patterns of ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) to stratify patients according to clinical outcomes, often with greater accuracy than traditional histopathological grading alone [19] [20] [21]. Methodologically, URPS development typically involves several standardized steps: (1) comprehensive URG collection from databases like iUUCD or GeneCards; (2) expression analysis in tumor versus normal tissues; (3) identification of URGs with prognostic significance through univariate Cox regression; (4) molecular subtyping of cancers based on URG expression patterns; and (5) construction of multivariable models using machine learning approaches such as LASSO Cox regression [20] [21].

In colon cancer, for instance, researchers have identified distinct molecular subtypes based on URG expression patterns that exhibit significant differences in overall survival, progression-free survival, immune cell infiltration, and pathological staging [21]. A study analyzing 1299 URGs in colon cancer classified patients into two molecular subtypes with markedly different clinical outcomes and immune microenvironment characteristics [21]. Similarly, a pan-cancer study developed a URPS that effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups across multiple cancer types, including lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma [19]. The high-risk group consistently demonstrated worse overall survival, validating the prognostic utility of ubiquitination signatures across diverse malignancies.

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination Regulators | Associated Tumor Grade/Stage | Functional Role | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon Cancer | ARHGAP4, MID2, SIAH2, TRIM45, UBE2D2, WDR72 | Advanced stage, poor prognosis | Immune microenvironment modulation, cell proliferation | qRT-PCR, immunohistochemistry, colony formation, EdU staining, xenograft models [21] |

| Pan-Cancer (Multiple) | OTUB1, TRIM28 | High-grade, therapy resistance | MYC pathway modulation, oxidative stress response | In vivo, in vitro, patient cohort analyses [19] |

| Breast Cancer | UBE2N/UBE2V1 complex | Metastatic disease | TGF-β signaling, NF-κB activation, MMP1 expression | ShRNA inhibition, metastasis mouse models [22] |

| Various Cancers | UBE2C | High-grade, aneuploidy | Chromosomal segregation, mitotic regulation | Transgenic mouse models, cell cycle analyses [22] |

Immune Microenvironment and Therapeutic Implications

Ubiquitination signatures not only reflect tumor grade but also shape the immune landscape of tumors, with significant implications for immunotherapy response. In colon cancer, patients classified into the high-risk URPS group exhibit characteristics indicative of enhanced epithelial-mesenchymal transition, immune escape, immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cell infiltration, regulatory T cell infiltration, and lower immunogenicity [21]. Conversely, the low-risk group demonstrates opposite trends but shows a better response to CTLA-4 checkpoint inhibitors [21]. These findings highlight how ubiquitination patterns influence tumor-immune interactions and may guide immunotherapeutic strategies.

The URPS also demonstrates value in predicting response to conventional therapies. For example, in the pan-cancer study, the ubiquitination score effectively predicted outcomes for patients receiving both surgery and immunotherapy [19]. This suggests that ubiquitination signatures capture fundamental biological features that determine therapeutic vulnerability, potentially guiding treatment selection across the cancer care continuum.

Key Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitination Signature Analysis

Transcriptomic Profiling and Computational Modeling

The delineation of ubiquitination signatures relies heavily on sophisticated transcriptomic analyses and computational approaches. Bulk RNA sequencing from large patient cohorts like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) provides the foundational data for identifying ubiquitination-related gene expression patterns associated with tumor grade and clinical outcomes [19] [20]. The standard analytical workflow includes data preprocessing (normalization, batch effect correction), differential expression analysis of URGs between tumor and normal tissues, consensus clustering to define molecular subtypes, and survival analysis to validate prognostic utility [20] [21].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has further enhanced resolution by enabling the dissection of ubiquitination signatures at cellular level within the complex tumor microenvironment [19]. This approach reveals how ubiquitination patterns vary between malignant cells, immune populations, and stromal components, providing insights into cell-type-specific regulatory mechanisms that influence tumor grade and behavior. Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) and single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) algorithms are then employed to quantify pathway activities and immune cell infiltration based on ubiquitination signatures [19] [20].

Machine learning techniques, particularly least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression and support vector machine recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE), are instrumental in refining ubiquitination signatures by identifying the most informative gene subsets for prognostic prediction [20] [21]. These computational methods effectively handle high-dimensional data while minimizing overfitting, yielding robust models that can be validated in independent patient cohorts.

Functional Validation Approaches

While computational analyses identify candidate ubiquitination signatures, functional validation is essential to establish causal relationships with tumor grade and progression. A multi-tiered experimental approach is typically employed, including:

In vitro models: Cell line models enable mechanistic studies of specific ubiquitination regulators. For example, knockdown experiments using siRNA or shRNA demonstrate how modulating specific E3 ligases or DUBs affects cancer cell phenotypes relevant to tumor grade, including proliferation, invasion, stemness, and therapy resistance [19] [22]. Colony formation and EdU staining assays quantitatively assess proliferative capacity, while migration and invasion assays evaluate metastatic potential [21].

In vivo models: Xenograft mouse models provide physiological context for evaluating how ubiquitination regulators influence tumor growth and progression. Orthotopic implantation models particularly recapitulate the tumor-microenvironment interactions that shape cancer behavior [21]. Spontaneous metastasis models further elucidate the role of ubiquitination in advanced disease [22].

Biochemical assays: Co-immunoprecipitation and ubiquitination assays directly demonstrate enzyme-substrate relationships and the effects of specific manipulations on ubiquitin chain formation [19]. For instance, the pan-cancer study validated that OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination regulates MYC pathway activity, establishing a direct molecular link between ubiquitination signatures and oncogenic signaling [19].

Clinical correlation: Immunohistochemistry on patient tissue microarrays correlates protein expression of ubiquitination regulators with tumor grade, stage, and clinical outcomes [21]. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) validates gene expression patterns in independent patient cohorts [21].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for developing and validating ubiquitination signatures in cancer research, integrating computational analyses with functional studies.

Key Regulatory Proteins and Pathways in Tumor Grading

E3 Ligases and Deubiquitinases as Grade-Associated Regulators

Specific E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes consistently emerge as critical regulators of tumor grade across cancer types. The E3 ligase TRIM28, identified in the pan-cancer ubiquitination analysis, forms a regulatory axis with OTUB1 that modulates MYC pathway activity and influences patient prognosis [19]. This ubiquitination-dependent regulation of MYC signaling represents a particularly significant finding, as MYC activation is a hallmark of aggressive, high-grade malignancies yet has proven notoriously difficult to target therapeutically.

In colon cancer, feature genes including ARHGAP4, MID2, SIAH2, TRIM45, UBE2D2, and WDR72 form the core of a prognostic signature that effectively stratifies patients by risk category [21]. Functional studies demonstrate that WDR72 knockdown significantly inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo, establishing its direct role in promoting aggressive tumor behavior [21]. Similarly, ARHGAP4 and SIAH2 show promising early diagnostic capabilities, suggesting their involvement from initial tumor development through progression to higher grades.

The E2 enzyme UBE2C exemplifies how ubiquitination regulators correlate with tumor grade across diverse cancer types. UBE2C overexpression is detected in breast, colon, prostate, ovarian, and lung cancers, where it causes chromosome missegregation and aneuploidy - cytological features associated with high-grade, poorly differentiated tumors [22]. Transgenic mouse models overexpressing UBE2C develop elevated lung tumor burden and various other malignancies, confirming its oncogenic potential [22].

Ubiquitination in Cancer Stemness and Metabolic Reprogramming

Ubiquitination pathways significantly influence two fundamental determinants of tumor grade: cancer stemness and metabolic reprogramming. The ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates the stability of core stem cell regulators including Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2, thereby modulating the self-renewal capacity and differentiation potential of cancer stem cells (CSCs) [12] [23]. As CSCs are increasingly recognized as drivers of tumor initiation, therapy resistance, and progression to higher grades, ubiquitination-dependent maintenance of stemness represents a crucial mechanism linking ubiquitination signatures to aggressive tumor behavior [23].

Similarly, ubiquitination orchestrates the metabolic adaptations that enable cancer cells to thrive in nutrient-poor environments and support rapid proliferation - characteristics of high-grade malignancies. Key metabolic enzymes including ACLY (ATP-citrate lyase) and FASN (fatty acid synthase) are regulated by ubiquitination, creating a direct molecular connection between the ubiquitin code and cancer-specific metabolic pathways [18]. In lung cancer, the E3 ligase NEDD4 targets ACLY for ubiquitination, thereby influencing lipid synthesis and tumor growth [18]. The deubiquitinase OTUB2 stabilizes pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) in colorectal cancer, enhancing glycolysis and accelerating disease progression [11]. These examples illustrate how ubiquitination signatures reflect and contribute to the metabolic reprogramming that underlies tumor progression.

Figure 2: Ubiquitination-dependent regulatory network driving high-grade tumor phenotypes through multiple interconnected mechanisms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Signature Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | iUUCD 2.0, GeneCards, STRING | Comprehensive URG identification and network analysis | Quality of manual curation, regular updates essential |

| Computational Tools | "ConsensusClusterPlus", "GSVA", "estimate" R packages | Molecular subtyping, pathway analysis, TME scoring | Parameter optimization, multiple algorithm comparison |

| Cell Line Models | Cancer cells with E3/DUB modulation | Functional validation of URGs | Use of CRISPR/Cas9, siRNA, or stable overexpression |

| Animal Models | Xenograft mouse models | In vivo tumorigenesis and metastasis assays | Orthotopic implantation improves physiological relevance |

| Antibodies | Phospho-specific, ubiquitin remnant antibodies | Western blot, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence | Validation for specific applications critical |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | UPS functional studies, therapeutic applications | Differential effects on constitutive vs immunoproteasomes |

| E1 Inhibitors | MLN7243, MLN4924 | Investigation of global ubiquitination blockade | Significant toxicity concerns |

| DUB Inhibitors | SIM0501 (USP1 inhibitor) | Targeting specific deubiquitination pathways | Selectivity profile requires verification |

| PROTACs | ARV-110, ARV-471 | Targeted protein degradation applications | Optimization of linker length and E3 recruiter |

The systematic investigation of ubiquitination signatures has fundamentally advanced our understanding of tumor biology and provides a powerful framework for refining cancer classification, prognosis, and treatment. The consistent correlation between specific ubiquitination patterns and tumor grade across diverse malignancies highlights the central role of ubiquitin signaling in cancer progression. As research in this field accelerates, several promising directions emerge for clinical translation and therapeutic development.

Ubiquitination signatures offer particular promise for addressing the challenge of tumor heterogeneity, both between patients and within individual tumors. The development of single-cell ubiquitination signatures could illuminate how distinct cellular subpopulations contribute to therapeutic resistance and disease progression, potentially guiding more effective combination therapies. Additionally, the integration of ubiquitination signatures with other molecular data types - including genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic profiles - may yield multi-dimensional classification systems that surpass the prognostic accuracy of current staging methods.

From a therapeutic perspective, the ubiquitination machinery presents novel opportunities for drug development. While proteasome inhibitors have established efficacy in hematological malignancies, newer approaches targeting specific E3 ligases or deubiquitinases offer the potential for greater selectivity and reduced toxicity [24]. The emergence of PROTAC (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimera) technology exemplifies how understanding ubiquitination mechanisms can enable entirely new therapeutic modalities that target previously "undruggable" oncoproteins [11]. Furthermore, the ability of ubiquitination signatures to predict immunotherapy response suggests their potential utility in guiding immune-based treatments, potentially expanding the benefit of these powerful therapies to more patients.

As methodologies continue to advance, particularly in mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics and single-cell technologies, we anticipate that ubiquitination signatures will become increasingly incorporated into clinical cancer diagnostics and therapeutic decision-making. The ongoing decoding of the ubiquitin code in cancer progression represents a frontier of molecular oncology with profound implications for improving patient outcomes across the spectrum of tumor grades and types.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism for protein degradation and function, playing a paradoxical role in cancer biology as both a guardian against malignant transformation and an accomplice in tumor progression [1]. Ubiquitination, the process whereby ubiquitin molecules are attached to substrate proteins, governs the stability, activity, and localization of virtually all intracellular proteins [11]. This post-translational modification involves a sequential enzymatic cascade comprising ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), which collectively determine the specificity and outcome of substrate modification [12]. The dynamic reversal of this process is mediated by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which remove ubiquitin chains and provide an additional layer of regulation [25].

The context-dependent nature of ubiquitination creates a complex landscape in oncology, where specific components can function as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on cellular context, tumor type, and stage of progression [26]. Oncogenic ubiquitination typically promotes the degradation of tumor suppressor proteins or enhances the stability and function of oncoproteins, thereby driving uncontrolled proliferation, evasion of growth suppression, and other cancer hallmarks [12]. In contrast, tumor-suppressive ubiquitination facilitates the elimination of oncoproteins, maintains genomic integrity, and regulates appropriate cell fate decisions [1]. Understanding this delicate balance is paramount for developing targeted therapeutic strategies that specifically modulate the UPS to restore normal cellular homeostasis in cancer cells [11].

Molecular Mechanisms of Ubiquitination

The Ubiquitination Machinery

The ubiquitination process initiates with E1 activating ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, forming a thioester bond between its catalytic cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [1] [12]. This activated ubiquitin is then transferred to an E2 enzyme, which collaborates with an E3 ligase to ultimately conjugate ubiquitin to lysine residues on substrate proteins [18]. The human genome encodes approximately 600 E3 ligases, which provide substrate specificity and determine the fate of modified proteins [12]. Based on their structural characteristics and mechanism of action, E3 ligases are classified into three main families: really interesting new gene (RING) finger domain-containing E3s, homology to E6AP C terminus (HECT) domain-containing E3s, and RING-between-RING (RBR) family E3s [25].

The consequences of ubiquitination are determined by the topology of ubiquitin chains. Monoubiquitination (attachment of a single ubiquitin) and multimonoubiquitination (multiple single ubiquitins on different lysines) typically regulate subcellular localization, protein activity, and endocytosis [11]. Polyubiquitination chains, formed through specific lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of ubiquitin, generate diverse biological signals [12]. K48-linked chains primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains mediate non-proteolytic functions such as signal transduction, DNA repair, and endocytic trafficking [25]. Other chain types, including K11, K29, and linear M1-linked chains, participate in cell cycle regulation, immune signaling, and other specialized functions [11].

The Deubiquitination Counterbalance

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) constitute a diverse family of proteases that reverse ubiquitination by cleaving ubiquitin from substrate proteins, thereby opposing the action of E3 ligases [18]. Approximately 100 DUBs are encoded in the human genome, categorized into seven subfamilies based on their catalytic domains: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Machado-Josephin domain proteases (MJDs), JAB1/MPN+/MOV34 (JAMM) domain proteases, monocyte chemotactic protein-induced proteins (MCPIPs), and motif interacting with ubiquitin-containing DUB family (MINDY) [25]. DUBs regulate ubiquitin homeostasis, process ubiquitin precursors, edit ubiquitin chains, and rescue substrates from proteasomal degradation, thereby fine-tuning ubiquitin signaling networks in cancer cells [27].

Figure 1: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Cascade. This diagram illustrates the sequential enzymatic process of ubiquitination, beginning with ubiquitin activation by E1 and culminating in substrate degradation by the proteasome following polyubiquitination.

Oncogenic Ubiquitination: Driving Tumor Progression

Enhanced Degradation of Tumor Suppressors

Oncogenic ubiquitination frequently manifests through the elevated activity of specific E3 ligases that target tumor suppressor proteins for destruction. A paradigm of this mechanism is the MDM2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53, a critical tumor suppressor mutated in over 50% of human cancers [26]. In normal cells, p53 induces MDM2 expression as part of a negative feedback loop, but cancer cells often overexpress MDM2, leading to excessive p53 degradation and uncontrolled proliferation [12]. Similarly, the SCFSkp2 E3 ligase complex targets multiple cell cycle inhibitors for degradation, including p27Kip1, p57Kip2, p130, and Tob1 [26]. Overexpression of Skp2 is observed in various human cancers and correlates with poor prognosis, while gene amplification of Skp2 has been identified in gastric cancers, solidifying its role as an oncogene [26].

The ubiquitination-mediated destruction of tumor suppressors extends beyond cell cycle regulators. The E3 ligase ARF-BP1 (Huwe1) ubiquitinates and promotes the degradation of p53 independent of MDM2, providing an alternative mechanism for p53 inactivation in cancer cells [26]. Additionally, BRCA1, a RING finger E3 ligase with crucial functions in DNA damage response, frequently undergoes somatic mutations in breast and ovarian cancers, compromising its tumor suppressor activity and genomic stability maintenance [26]. These examples illustrate how diverse E3 ligases converge on critical tumor suppressor pathways to enable malignant transformation and progression.

Stabilization of Oncoproteins

Oncogenic ubiquitination also operates through the stabilization of oncoproteins, either directly through atypical ubiquitin linkages that enhance protein function rather than degradation, or indirectly through the inactivation of E3 ligases that normally target oncoproteins for destruction [12]. The deubiquitinating enzyme OTUB2 exemplifies this mechanism by interacting with pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) and inhibiting its ubiquitination by the E3 ligase Parkin, thereby enhancing glycolysis and accelerating colorectal cancer progression [11]. Similarly, USP2 stabilizes programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) through deubiquitination, promoting tumor immune escape and resistance to immunotherapy [11].

The metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells is particularly dependent on ubiquitination-mediated stabilization of oncoproteins. TRAF6, an E3 ligase upregulated in cancer cells, mediates K63-linked polyubiquitination of mTOR under amino acid stimulation, promoting mTORC1 translocation to lysosomes and subsequent activation [25]. This ubiquitination event enhances mTORC1 signaling, driving metabolic adaptations that support cancer cell growth and proliferation. Additionally, reduced K48-linked ubiquitination of mTOR by E3 ligases FBX8 and FBXW7 decreases proteasome-dependent degradation, further sustaining oncogenic mTOR signaling in cancer cells [25].

Table 1: Key E3 Ubiquitin Ligases with Oncogenic Functions in Cancer

| E3 Ligase | Substrate(s) | Cancer Type(s) | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDM2 | p53 | Various (multiple cancer types) | Enhanced proliferation, evasion of apoptosis |

| SCFSkp2 | p27Kip1, p57Kip2, p130, Tob1 | Gastric, various | Cell cycle progression, uncontrolled proliferation |

| ARF-BP1 (Huwe1) | p53 | Various | Apoptosis evasion, genomic instability |

| TRAF6 | mTOR | Various | Metabolic reprogramming, enhanced growth |

| RNF2 | Histone H2A | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Enhanced metastatic potential |

Tumor-Suppressive Ubiquitination: Constraining Malignancy

Degradation of Oncoproteins

Tumor-suppressive ubiquitination primarily functions through the targeted degradation of oncoproteins, preventing their accumulation and subsequent驱动 of malignant phenotypes. The Fbw7 (F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7) E3 ligase represents a critical tumor suppressor that targets multiple oncoproteins for ubiquitin-mediated degradation, including Cyclin E, c-Myc, c-Jun, c-Myb, Notch, and mTOR [26]. Fbw7 recognizes specific phosphodegron motifs in its substrates and is frequently deleted or mutated in human cancers, leading to stabilization of its oncogenic targets and accelerated tumor development [26]. Conditional inactivation of Fbw7 in mouse models results in thymic hyperplasia due to c-Myc accumulation, eventually progressing to thymic lymphoma, confirming its bona fide tumor suppressor function [26].

The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) represents another crucial tumor-suppressive E3 ligase that controls cell cycle progression by targeting key regulators for degradation, including cyclins and securin [28]. Proper APC/C function ensures accurate cell division and prevents chromosomal instability, a hallmark of cancer. The specificity of APC/C is determined by its interactions with coactivators Cdc20 and Cdh1, which recognize distinct substrates during different cell cycle phases. Dysregulation of APC/C activity contributes to uncontrolled proliferation and genomic instability in various cancers, underscoring its importance as a tumor suppressor [28].

Regulation of DNA Repair and Genomic Integrity

Tumor-suppressive ubiquitination plays essential roles in maintaining genomic integrity through the regulation of DNA damage response pathways. BRCA1, in complex with BARD1, forms a RING finger E3 ligase heterodimer that participates in DNA repair processes, cell cycle checkpoint control, and centrosome duplication [26]. The ubiquitin ligase activity of the BRCA1-BARD1 complex is crucial for its tumor suppressor function, as mutations that disrupt this activity are frequently identified in hereditary breast and ovarian cancers [26]. Unlike typical degradation signals, BRCA1-BARD1-mediated ubiquitination of RNA polymerase II and RPB8 in response to DNA damage does not necessarily lead to proteasomal degradation but rather facilitates DNA repair processes through non-proteolytic mechanisms [26].

Monoubiquitination events also contribute to tumor-suppressive functions, particularly in DNA damage response. The monoubiquitination of histone H2AX (γH2AX) by UBE2T regulates the phosphorylation of cell cycle checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1), influencing DNA repair efficiency and maintaining genomic stability [11]. Additionally, the E3 ligase Rad18 mediates monoubiquitination of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in response to DNA damage, facilitating the recruitment of specialized DNA polymerases that enable error-prone translation synthesis, a double-edged sword that promotes survival but also increases mutation rates [12]. These DNA damage-associated ubiquitination events represent critical tumor-suppressive mechanisms that prevent the accumulation of oncogenic mutations.

Table 2: Key E3 Ubiquitin Ligases with Tumor-Suppressive Functions in Cancer

| E3 Ligase | Substrate(s) | Cancer Type(s) | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fbw7 | Cyclin E, c-Myc, c-Jun, c-Myb, Notch | Various (frequently mutated) | Cell cycle control, proliferation inhibition |

| APC/C | Cyclins, Securin | Various | Cell cycle regulation, genomic stability |

| BRCA1-BARD1 | RNA polymerase II, RPB8 | Breast, ovarian | DNA damage repair, genomic integrity |

| Parkin | PKM2 | Colorectal cancer | Metabolic regulation, inhibition of glycolysis |

| CUL3-KLHL25 | ACLY | Lung cancer | Inhibition of lipid synthesis |

Context-Dependent Roles in Cancer Hallmarks

Metabolic Reprogramming

Ubiquitination exerts profound influence on cancer metabolism, regulating key enzymes and signaling pathways that drive metabolic reprogramming. The ubiquitin-mediated regulation of adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase (ACLY), a crucial enzyme linking glycolysis to lipid synthesis, demonstrates the context-dependent nature of ubiquitination in cancer metabolism [18]. The Cullin 3 E3 ligase complex, through its adaptor protein KLHL25, ubiquitinates and degrades ACLY, thereby inhibiting lipid synthesis and suppressing tumor growth in lung cancer [18]. Conversely, ARHGEF3 enhances ACLY stability by reducing its association with the E3 ligase NEDD4, promoting lipogenesis and cancer proliferation [18]. This opposing regulation highlights how different E3 ligases can exert antagonistic effects on the same metabolic enzyme, creating a balance that is disrupted in cancer.

The ubiquitination of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), a key glycolytic enzyme in cancer cells, further illustrates the complex regulation of cancer metabolism. The E3 ligase Parkin facilitates the ubiquitination of PKM2, while the deubiquitinating enzyme OTUB2 inhibits this process by interacting with PKM2, thereby enhancing glycolysis and accelerating colorectal cancer progression [11]. This opposition between ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating enzymes creates a regulatory switch that controls metabolic flux in cancer cells. Similarly, fatty acid synthase (FASN), a critical enzyme in de novo lipogenesis, is regulated by multiple E3 ligases including COP1 and TRIM21, which target FASN for degradation in a context-dependent manner [18]. The tumor suppressor SPOP, an E3 ubiquitin ligase frequently mutated in prostate cancer, regulates lipid metabolism by reducing FASN expression and fatty acid synthesis, highlighting the metabolic dimension of its tumor-suppressive function [18].

Immune Evasion and Tumor Microenvironment

The ubiquitin-proteasome system plays a pivotal role in regulating tumor immune responses, particularly through the modulation of immune checkpoint proteins. The programmed cell death 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) axis, a critical immune checkpoint, is extensively regulated by ubiquitination [11]. USP2, a deubiquitinating enzyme, stabilizes PD-1 through deubiquitination, promoting tumor immune escape and resistance to immunotherapy [11]. Conversely, metastasis suppressor protein 1 (MTSS1) promotes the monoubiquitination of PD-L1 at K263 mediated by the E3 ligase AIP4, leading to PD-L1 internalization, endosomal transport, and lysosomal degradation, thus inhibiting immune escape in lung adenocarcinoma [11]. This opposing regulation of immune checkpoints by ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating enzymes offers promising therapeutic opportunities for enhancing cancer immunotherapy.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is additionally shaped by ubiquitination through its effects on immune cell function and cytokine signaling. Linear ubiquitination, mediated by the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), regulates NF-κB signaling and impacts cancer development and immune responses [11]. HOIP, a component of LUBAC, promotes lymphoma by activating NF-κB signaling, suggesting LUBAC as a therapeutic target for B-cell lymphoma [11]. Additionally, Epsin, a member of the ubiquitin-binding endocytosis adaptor protein family, interacts with LUBAC to facilitate linear ubiquitination of NEMO, contributing to breast cancer progression [11]. These findings highlight the diverse mechanisms through which ubiquitination shapes the tumor immune microenvironment and influences cancer progression.

Figure 2: Oncogenic versus Tumor-Suppressive Ubiquitination in Cancer Hallmarks. This diagram illustrates how different ubiquitination patterns influence key hallmarks of cancer through distinct molecular mechanisms.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Assessing Ubiquitination in Cancer Models

The investigation of ubiquitination pathways in cancer relies on a combination of molecular, cellular, and biochemical techniques that enable the detection and quantification of ubiquitination events, identification of relevant enzymes and substrates, and functional characterization of specific modifications. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) followed by western blotting represents a fundamental approach for detecting protein-protein interactions and ubiquitination status in cancer cells [28]. Typically, cells are transfected with plasmids expressing ubiquitin and the protein of interest, treated with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132) to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins, and lysed under denaturing or non-denaturing conditions depending on the interaction stability. Immunoprecipitation using specific antibodies against the protein of interest is followed by western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies to detect ubiquitination [25].

In vivo and in vitro ubiquitination assays provide more direct evidence for ubiquitination events and can identify specific E3 ligases responsible for substrate modification. For in vitro ubiquitination assays, purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ubiquitin, and the substrate protein are incubated in reaction buffer containing ATP, followed by western blot analysis to detect ubiquitinated substrates [25]. In vivo ubiquitination assays involve transfection of ubiquitin and relevant E3 ligases into cells, treatment with proteasome inhibitors, immunoprecipitation of the substrate, and detection of ubiquitination by western blotting [12]. These approaches are complemented by mass spectrometry-based proteomics, which enables global identification of ubiquitination sites and quantification of ubiquitin chain topology in cancer cells under different conditions [21].

Functional Validation in Cancer Models

Functional validation of ubiquitination pathways in cancer biology employs genetic and pharmacological approaches to modulate specific components of the ubiquitin system and assess resulting phenotypic changes. RNA interference (RNAi) techniques, including small interfering RNA (siRNA) and short hairpin RNA (shRNA), are widely used to knock down expression of specific E3 ligases or DUBs in cancer cells, enabling assessment of their effects on substrate stability, signaling pathways, and malignant phenotypes [28] [21]. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene knockout provides a more permanent and complete elimination of target genes, allowing comprehensive analysis of their functions in cancer progression and therapeutic responses [21].