Ubiquitination-Related Gene Signatures: Novel Prognostic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Guides in Cancer

Ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, is increasingly recognized for its role in tumorigenesis, progression, and therapy response.

Ubiquitination-Related Gene Signatures: Novel Prognostic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Guides in Cancer

Abstract

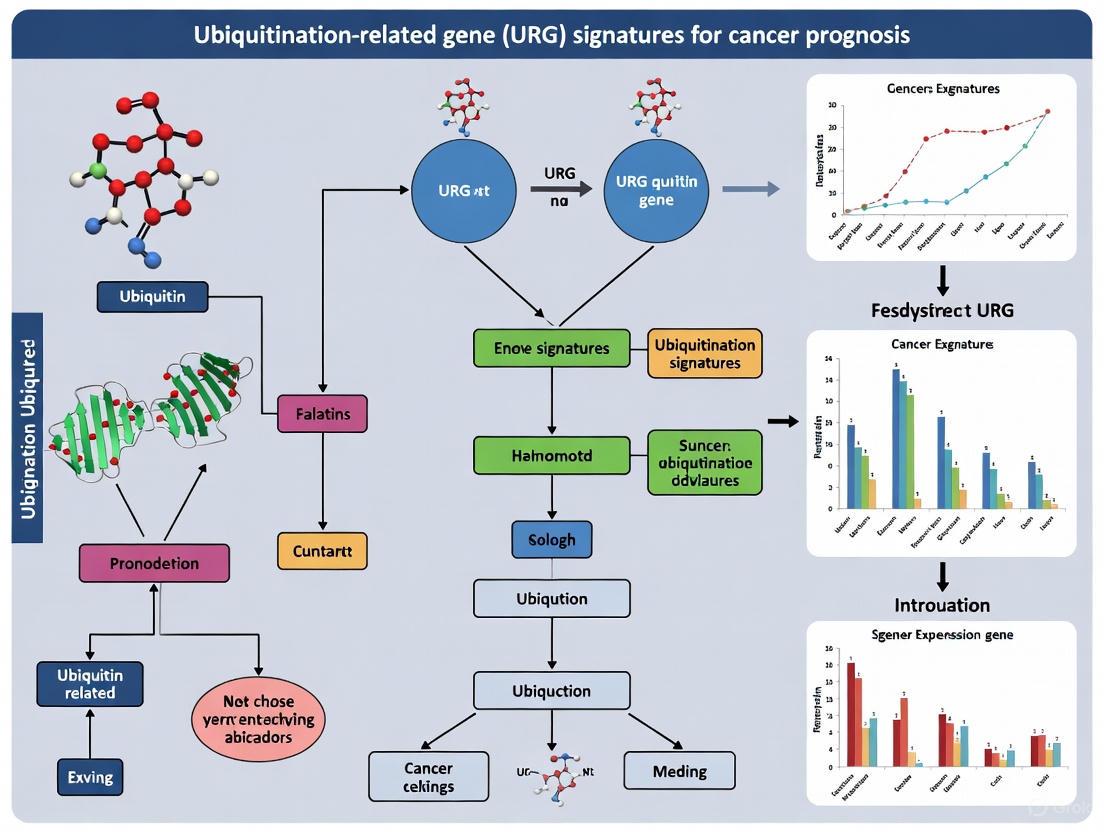

Ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, is increasingly recognized for its role in tumorigenesis, progression, and therapy response. This article synthesizes current research on ubiquitination-related gene (URG) signatures as powerful prognostic tools across multiple cancers, including colon, breast, pancreatic, and cervical cancer. We explore the foundational biology of ubiquitination in cancer, detail the bioinformatic methodologies for developing multi-gene signatures, address key challenges in optimization and clinical translation, and evaluate validation frameworks and comparative performance against established biomarkers. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review highlights the potential of URGs to refine risk stratification, illuminate tumor microenvironment interactions, and ultimately guide the development of personalized oncology therapeutics.

The Ubiquitin System: From Basic Biology to Cancer Prognosis

Ubiquitination is a crucial reversible post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology, from protein degradation to cell signaling, DNA repair, and immune responses [1]. This sophisticated enzymatic system operates through a sequential cascade involving E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligase) enzymes, which collaboratively attach the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins. The specificity and outcomes of ubiquitination are remarkably diverse—a single ubiquitin (monoubiquitination) or multiple ubiquitins forming chains (polyubiquitination) can be attached to substrates, with at least eight distinct linkage types (Met1, Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, Lys63) creating a complex "ubiquitin code" that determines functional consequences [2] [1]. The reverse reaction, deubiquitination, is carried out by deubiquitinases (DUBs), which hydrolyze ubiquitin-substrate and ubiquitin-ubiquitin bonds, providing dynamic regulation of ubiquitin signaling [3] [4]. This elaborate system maintains cellular homeostasis by controlling protein stability, localization, and activity, with particular relevance to cancer biology where ubiquitination-related gene (URG) signatures are emerging as powerful prognostic tools.

The Ubiquitination Cascade: Mechanism and Key Enzymes

The Enzymatic Pathway

The ubiquitination cascade is an ATP-dependent process that requires the sequential action of three enzyme families [2] [5]:

- E1 Ubiquitin-Activating Enzymes: A single E1 enzyme (Uba1 in humans) initiates the cascade by activating ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a thioester bond between its catalytic cysteine and the C-terminus of ubiquitin [6] [5].

- E2 Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes: The activated ubiquitin is transferred to the catalytic cysteine of an E2 enzyme via a transthiolation reaction. Humans express several dozen E2s that influence the type of ubiquitin chain formed [6] [7].

- E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: E3s recruit E2~Ub complexes and substrate proteins, facilitating ubiquitin transfer. With over 600 members in humans, E3s provide substrate specificity to the ubiquitin system [2] [8].

Table 1: Major Enzyme Classes in the Ubiquitin System

| Enzyme Class | Number in Humans | Core Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | 2 [7] | Ubiquitin activation | ATP-dependent; forms E1~Ub thioester; gatekeeper of ubiquitin conjugation |

| E2 (Conjugating) | Several dozen [7] | Ubiquitin carriage | Determines ubiquitin chain type; forms E2~Ub thioester; interacts with E3s |

| E3 (Ligase) | 500-1000 [2] [8] | Substrate recognition | Provides specificity; directly or indirectly catalyzes ubiquitin transfer |

| DUBs | ~100 [3] | Ubiquitin removal | Cleaves ubiquitin from substrates; recycles ubiquitin; edits ubiquitin chains |

The final step of ubiquitination involves an attack on the E2~Ub thioester bond by a lysine ε-amino group from the substrate protein, forming a stable isopeptide bond. In RING E3 ligases, ubiquitin is transferred directly from the E2 to the substrate, while in HECT and RBR E3s, ubiquitin is first transferred to the E3 before substrate modification [2] [8].

E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Structural Families

E3 ubiquitin ligases are classified into four major families based on their structural features and mechanism of action [2] [8]:

- RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3 Ligases: The largest E3 family, characterized by a RING domain that binds E2s and facilitates direct ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate. RING E3s can function as monomers or multi-subunit complexes like cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) [2].

- HECT (Homologous to E6AP C-Terminus) E3 Ligases: Contain a HECT domain that forms a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to substrates. The HECT family includes Nedd4, HERC, and other HECT subfamilies with distinct protein-interaction domains [2].

- RBR (RING-Between-RING-RING) E3 Ligases: Hybrid mechanisms incorporating aspects of both RING and HECT E3s. RBRs contain a RING1 domain that binds E2~Ub, then transfer ubiquitin to a catalytic cysteine in the RING2 domain before substrate modification [7].

- U-box E3 Ligases: Structurally similar to RING E3s but stabilized by different interactions, functioning as E3/E4 enzymes in ubiquitination processes [2].

The Ubiquitin Code and Cellular Functions

Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Functional Consequences

The ubiquitin code derives from the ability of ubiquitin itself to be modified on its seven lysine residues or N-terminal methionine, creating structurally and functionally distinct polyubiquitin signals [2] [1]:

Table 2: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Major proteasomal degradation signal [2] | Targets substrates to 26S proteasome |

| K63-linked | DNA repair, cytokine signaling, autophagy, endocytosis [2] | Non-proteolytic signaling roles |

| Met1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB activation, immune signaling [2] [1] | Assembled by LUBAC complex; regulates inflammation |

| K11-linked | Cell cycle regulation, proteasomal degradation [2] | Involved in ER-associated degradation |

| K27-linked | Protein secretion, DNA damage repair, mitochondrial quality control [2] | Associated with Parkin E3 ligase |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal degradation, innate immune response [2] | Regulates AMPK-related kinases |

| K6-linked | DNA damage response [2] | Less characterized; implicated in genomic stability |

| K33-linked | Intracellular trafficking, regulation of IFN signaling [2] | Controls kinase activity and trafficking |

Deubiquitinases (DUBs): Regulation of the Ubiquitin Code

Deubiquitinases counterbalance ubiquitin signaling by removing ubiquitin modifications from substrate proteins. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, categorized into seven families based on their catalytic mechanisms [3] [4]:

- Cysteine Protease DUB Families: Include ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Josephins, MINDY, and ZUFSP. These utilize a catalytic triad of Cys, His, and Asp/Asn residues for nucleophilic attack on the isopeptide bond [3].

- Metalloprotease DUB Family: JAB1/MPN/MOV34 (JAMM) domain DUBs use a catalytic zinc ion for hydrolysis [3].

DUBs perform three major cellular functions: (1) generating free ubiquitin from linear gene-encoded fusions; (2) trimming polyubiquitin chains to edit signals; and (3) reversing ubiquitin signals by removing ubiquitin from modified proteins [3]. Their dysregulation is implicated in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and immune disorders, making them attractive therapeutic targets [3] [4].

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Research

Protocol 1: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

Purpose: To reconstitute ubiquitination of a specific substrate and characterize E1-E2-E3 interactions.

Materials:

- Purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes, and substrate protein

- Ubiquitin, ATP, and energy regeneration system

- Reaction buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT

Method:

- Prepare master mix containing 2.5 μM E1, 5-10 μM E2, and 2.5-5 μM E3 in reaction buffer

- Add 5-10 μM substrate, 50 μM ubiquitin, and 2 mM ATP with energy regeneration system

- Incubate at 30°C for 0-120 minutes, taking timepoints at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes

- Stop reactions with SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing 50 mM DTT

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with ubiquitin-specific and substrate-specific antibodies

- For chain linkage specificity, use linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., anti-K48, anti-K63)

Technical Notes: For structural studies, disulfide crosslinking strategies can stabilize E1-E2 complexes as demonstrated in Uba1-Cdc34 structural studies [6]. E2-E3 specificity can be mapped by testing different E2 combinations with a specific E3.

Protocol 2: Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Analysis

Purpose: To determine the specific polyubiquitin chain linkage types assembled by an E2-E3 pair.

Materials:

- Ubiquitin mutants (K48R, K63R, K48-only, K63-only, etc.)

- Linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies

- Mass spectrometry reagents: trypsin, Glu-C, chromatographic materials

Method:

- Set up ubiquitination reactions with wild-type and lysine-mutant ubiquitins

- For antibody-based detection:

- Perform Western blotting with linkage-specific antibodies

- Compare migration patterns with mutant ubiquitins that restrict chain formation

- For mass spectrometry analysis:

- Enrich ubiquitinated substrates via immunoaffinity purification

- Digest with trypsin/Glu-C to generate signature ubiquitin peptides

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS for identification of linkage-specific diGly remnants

- Quantify relative abundance of different chain types

Technical Notes: K48-linked chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains mediate signaling functions [2]. RING E3s generally allow E2s to determine linkage specificity, while HECT and RBR E3s often dictate chain topology [7].

Visualization of Ubiquitin Signaling

The Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

The Ubiquitin Code and Cellular Outcomes

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzymes | Recombinant Uba1, Uba6 | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Essential for initial ubiquitin activation; ATP-dependent |

| E2 Enzymes | Cdc34, UbcH5, Ubc13 | Chain formation studies | Determines ubiquitin chain linkage specificity [6] |

| E3 Ligases | MDM2, Parkin, c-Cbl, APC/C | Substrate specificity studies | Over 600 human E3s provide substrate recognition [2] [8] |

| DUBs | USP14, UCH37, OTUB1 | Deubiquitination assays | Cleave ubiquitin from substrates; edit ubiquitin chains [3] |

| Ubiquitin Variants | K48-only, K63-only, K48R | Chain linkage analysis | Determine specificity of ubiquitin chain formation |

| Linkage-specific Antibodies | Anti-K48, Anti-K63, Anti-M1 | Western blot, immunofluorescence | Identify specific ubiquitin chain linkages |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132 | Functional validation | Block proteasomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619, b-AP15 | DUB functional studies | Investigate DUB roles in cellular pathways [4] |

Cancer Prognosis Applications of Ubiquitination-Related Genes

Ubiquitination-related gene (URG) signatures are emerging as powerful tools for cancer prognosis and treatment stratification. In breast cancer, the 70-gene MammaPrint signature has been validated in prospective clinical trials for predicting recurrence risk and guiding adjuvant chemotherapy decisions [9]. Similarly, in colorectal cancer, the 12-gene Oncotype DX assay stratifies Stage II/III patients by recurrence risk, though clinicopathological factors like T stage and mismatch repair status remain important [9]. For hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), multiple mRNA, lncRNA, and miRNA signatures have been developed, including a 5-gene signature (HN1, RAN, RAMP3, KRT19, TAF9) that predicts survival across diverse patient cohorts [9]. The molecular subtyping of cancers based on URGs reveals distinct biological behaviors—proliferation-class HCCs characterized by chromosomal instability versus non-proliferation class with better differentiation [9]. These URG signatures refine traditional TNM staging by capturing the underlying biological heterogeneity of tumors, enabling more personalized treatment approaches. However, challenges remain in standardizing analytical approaches, validating signatures across diverse populations, and translating these molecular tools into routine clinical practice.

The ubiquitin system represents a sophisticated regulatory network that maintains cellular homeostasis through precise control of protein fate and function. The enzymatic cascade of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes creates a diverse ubiquitin code that is dynamically interpreted and edited by DUBs to regulate virtually all cellular processes. Understanding the mechanisms and specificity of these enzymes provides critical insights into disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer, where ubiquitination-related gene signatures are emerging as valuable prognostic and predictive biomarkers. Continued research on ubiquitination mechanisms, combined with advanced proteomic and genomic technologies, will accelerate the development of targeted therapies and precision medicine approaches that exploit the ubiquitin system for therapeutic benefit.

Ubiquitination Dysregulation as a Hallmark of Cancer Pathogenesis

Ubiquitination is a critical, reversible, and enzymatically regulated post-translational modification that serves as a fundamental regulatory mechanism governing cellular homeostasis. This process orchestrates a vast array of cellular functions including targeted proteolysis, metabolism, signal transduction, and cell cycle regulation [10]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) comprises ubiquitin and its degradation by the proteasome, responsible for 80–90% of cellular proteolysis [10]. The ubiquitination process is regulated through a cascade of reactions mediated by ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), while ubiquitin chains can be removed by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [10].

Dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways represents a fundamental hallmark of cancer pathogenesis, contributing to various aspects of tumor development and progression. Ubiquitination plays a crucial regulatory role in tumor metabolic reprogramming and is involved in processes including cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation [10]. Furthermore, it influences protein levels of immune checkpoint regulators like PD-1/PD-L1 in the tumor microenvironment, thereby modulating immunotherapy efficacy [10]. This application note explores the multifaceted roles of ubiquitination dysregulation in cancer and provides detailed protocols for investigating ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures and mechanisms.

Ubiquitination-Related Gene Signatures as Prognostic Biomarkers

Pan-Cancer Ubiquitination Signatures

Recent multi-cancer analyses have revealed that ubiquitination-related gene signatures provide powerful prognostic biomarkers across diverse cancer types. A comprehensive study integrating data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts spanning five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma) identified key nodes and prognostic pathways within the ubiquitination-modification network [10]. This research established a conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) that effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes across all analyzed cancers [10].

The URPS demonstrated significant value as a novel biomarker for predicting immunotherapy response, with the potential to identify patients most likely to benefit from immunotherapy in clinical settings [10]. At single-cell resolution, URPS enabled more precise classification of distinct cell types and was associated with macrophage infiltration within the tumor microenvironment [10]. Experimental validation confirmed that the OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination regulatory axis plays a crucial role in modulating the MYC pathway and influencing patient prognosis [10].

Tissue-Specific Ubiquitination Signatures

Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD)

In lung adenocarcinoma, ubiquitination-related risk scores (URRS) calculated from the expression of four genes (DTL, UBE2S, CISH, and STC1) effectively stratified patient prognosis [11]. Patients with higher URRS had significantly worse outcomes (Hazard Ratio [HR] = 0.54, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.39–0.73, p < 0.001), a finding validated across six external cohorts (Hazard Ratio [HR] = 0.58, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.36–0.93, pmax = 0.023) [11]. The high URRS group exhibited higher PD1/L1 expression levels (p < 0.05), tumor mutation burden (TMB, p < 0.001), tumor neoantigen load (TNB, p < 0.001), and tumor microenvironment scores (p < 0.001) [11].

Table 1: Key Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Genes in Lung Adenocarcinoma

| Gene | Function | Prognostic Association | Potential Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTL | Ubiquitin ligase component | Worse prognosis with upregulation | Potential therapeutic target |

| UBE2S | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 | Worse prognosis with upregulation | Linked to chemotherapy response |

| CISH | Cytokine inducible SH2-containing protein | Better prognosis with upregulation | Immunomodulatory role |

| STC1 | Secreted glycoprotein | Worse prognosis with upregulation | Associated with tumor progression |

Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC)

Comprehensive analysis of ESCC identified 85 ubiquitination-related differentially expressed genes (URDEGs), with five key genes (BUB1B, CHEK1, DNMT1, IRAK1, and PRKDC) demonstrating significant prognostic value [12]. These genes play essential roles in critical processes such as cell cycle regulation and immune response, and their varied expression in ESCC tissues supports their potential as therapeutic targets [12].

Gastric Cancer

In gastric cancer, USP2 expression was significantly reduced in cancer cells and patient samples (p < 0.05) [13]. Patients with low USP2 expression were primarily associated with genetic variations, neoantigen loads, microsatellite instability (MSI) scores, and immune cell infiltration (p < 0.05) [13]. Functional experiments demonstrated that USP2 overexpression suppressed proliferation, migration, and cell cycle progression while enhancing apoptosis in gastric cancer cells [13].

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Research

Protocol 1: Detecting Protein Ubiquitination Modification

This protocol describes a standardized method for detecting K27-linked polyubiquitination of mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), which can be adapted for other proteins of interest [14].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Detection

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specification | Function/Application | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 293T cells | Human embryonic kidney cell line | Protein expression platform | [14] |

| HA-Ub-K27 plasmid | Expresses HA-tagged ubiquitin with only K27 residue | Specific ubiquitination detection | [14] |

| Myc-MAVS plasmid | Myc-tagged mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein | Target protein for ubiquitination | [14] |

| Anti-Myc antibody | Monoclonal antibody (9E10) | Immunoprecipitation of target protein | Santa Cruz, sc-40 [14] |

| Anti-HA-tag antibody | Polyclonal antibody | Detection of ubiquitinated proteins | GenScript, A00168 [14] |

| Protein G PLUS-Agarose | Agarose conjugate | Antibody binding for immunoprecipitation | Santa Cruz, sc-2002 [14] |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Inhibits protein degradation | Maintains protein integrity during processing | Cell Signaling Technology, 5871S [14] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Cell Preparation and Transfection (Timing: 24 hours)

- Passage 293T cells when 90% confluent in 10 cm dishes

- Transfect cells with plasmids encoding HA-Ub-K27, Myc-MAVS, and relevant experimental vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent according to manufacturer's instructions

- Incubate cells for 24-48 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂ to allow protein expression

Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction (Timing: 1 hour)

- Aspirate media and wash cells with 3 mL ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Lyse cells in 1 mL IP lysis buffer (supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM PMSF) per 10 cm dish

- Incubate on ice for 30 minutes with occasional vortexing

- Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet cell debris

- Transfer supernatant to fresh tubes for immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation (Timing: 4 hours to overnight)

- Pre-clear lysates by incubating with 20 μL Protein G PLUS-Agarose for 30 minutes at 4°C

- Centrifuge at 2,500 × g for 5 minutes and transfer supernatant to new tubes

- Add 1-5 μg anti-Myc antibody (for exogenous protein) or anti-MAVS antibody (for endogenous protein) per 500 μg total protein

- Incubate with rotation for 2 hours at 4°C

- Add 20 μL Protein G PLUS-Agarose and continue incubation overnight at 4°C

Western Blot Detection (Timing: 6 hours)

- Wash beads three times with 1 mL ice-cold lysis buffer

- Elute proteins by boiling in 2× SDS loading buffer for 10 minutes

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membrane

- Block membrane with 5% non-fat milk in TBST for 1 hour

- Incubate with primary antibodies (anti-HA for exogenous ubiquitination or anti-ub-K27 for endogenous ubiquitination) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C

- Incubate with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature

- Develop using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Detecting Protein Ubiquitination

Protocol 2: Developing Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures

This protocol outlines the bioinformatics approach for constructing ubiquitination-related risk models based on methodologies successfully applied in lung adenocarcinoma and other cancers [11].

Data Collection and Preprocessing

Data Acquisition

- Obtain gene expression profiles and corresponding clinical datasets from public repositories (TCGA, GEO)

- Collect ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) from specialized databases (iUUCD 2.0: http://iuucd.biocuckoo.org/)

- For TCGA-LUAD datasets, retain only cancerous tissues, excluding formalin-fixed samples and recurrent tissues

- Filter patients with survival time of fewer than 3 months

Data Normalization and Filtering

- Normalize RNA-seq data using appropriate methods (e.g., FPKM, TPM)

- Perform quality control to remove low-quality samples

- Annotate clinical endpoints (overall survival, progression-free survival)

Molecular Subtype Identification

Consensus Clustering

- Apply unsupervised clustering using the "ConsensusClusterPlus" R package

- Set parameters: maxK = 5, reps = 1000, pItem = 0.8, pFeature = 1, clusterAlg="km", distance="euclidean"

- Repeat clustering 1000 times to ensure classification stability

- Explore prognostic performance and clinical features across molecular subtypes

Differential Expression Analysis

- Identify differently expressed URGs between molecular subtypes using "limma" R package

- Apply filtering thresholds: adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 0.8

Prognostic Model Construction

Feature Selection

- Perform univariate Cox regression analysis to identify prognostic URGs

- Apply Random Survival Forest algorithm (variable importance > 0.25) using "randomForestSRC" package

- Conduct LASSO Cox regression algorithm using "cv.glmnet" function (family='cox', type.measure = 'deviance')

- Select overlapping genes identified by all three methods

Risk Score Calculation

- Perform multivariate Cox regression analysis on selected genes

- Calculate ubiquitination-related risk scores (URRS) using the formula: [ Risk\,score = \sum \beta{RNA} * Exp{RNA} ] where βRNA represents the coefficient from multivariate Cox regression and ExpRNA represents gene expression levels

- Stratify patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on median risk score

Model Validation

- Validate prognostic performance in independent external datasets

- Evaluate time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves

- Assess calibration and discrimination metrics

Key Ubiquitination Pathways in Cancer Pathogenesis

OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC Regulatory Axis

Experimental studies have revealed that the OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination regulatory enzyme influences the histological fate of cancer cells by modulating MYC and its downstream targets, while altering oxidative stress pathways [10]. This regulation ultimately leads to immunotherapy resistance and poor prognosis in patients. Ubiquitination score positively correlates with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma [10].

Figure 2: OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC Ubiquitination Regulatory Axis in Cancer

USP22 in Oncogenic Signaling

USP22 regulates oncogenic signaling pathways to drive lethal tumor phenotypes by modulating nuclear receptor and oncogenic signaling [15]. In multiple xenograft models of human cancer, USP22 deregulation demonstrated control over androgen receptor (AR) accumulation and signaling, enhancing expression of critical target genes co-regulated by AR and MYC [15]. USP22 not only reprogrammed AR function but was sufficient to induce the transition to therapeutic resistance [15].

Table 3: Key Ubiquitination-Related Enzymes in Cancer Pathogenesis

| Enzyme | Class | Cancer Types Involved | Mechanism of Action | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP22 | Deubiquitinase | Prostate, Breast | Modulates AR and MYC signaling; promotes therapeutic resistance | Potential target for advanced disease |

| OTUB1 | Deubiquitinase | Multiple solid tumors | Regulates MYC pathway; influences oxidative stress | Impacts immunotherapy response |

| USP2 | Deubiquitinase | Gastric, Various | Stabilizes oncoproteins (EGFR, MDM2, CyclinD1) | Downregulation indicates poor prognosis in gastric cancer |

| UBE2S | Ubiquitin-conjugating E2 | Lung adenocarcinoma | Promotes tumor progression | Component of prognostic signature |

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Implications

Prognostic Stratification

Ubiquitination-related gene signatures provide robust tools for prognostic stratification across multiple cancer types. The URPS effectively identifies patient subgroups with distinct survival outcomes and molecular characteristics [10]. Similarly, the URRS model in lung adenocarcinoma enables identification of high-risk patients who may benefit from more aggressive therapeutic interventions [11].

Predicting Treatment Response

Ubiquitination signatures demonstrate significant value in predicting response to various cancer treatments:

Immunotherapy Prediction: URPS serves as a novel biomarker for predicting immunotherapy response, potentially identifying patients more likely to benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors [10].

Chemotherapy Sensitivity: In lung adenocarcinoma, the IC50 values of various chemotherapy drugs were significantly lower in the high URRS group, indicating increased sensitivity [11].

Targeted Therapy Development: Ubiquitination regulatory modifiers for traditionally "undruggable" targets like MYC can be screened through constructed pan-cancer ubiquitination regulatory networks, providing new therapeutic alternatives [10].

Technical Considerations and Limitations

When implementing ubiquitination-related prognostic models, several technical considerations merit attention:

Platform Compatibility: Ensure consistent normalization across different gene expression platforms when validating signatures in independent datasets.

Sample Quality: Use high-quality RNA samples with minimal degradation to ensure accurate quantification of ubiquitination-related genes.

Multicenter Validation: Prospective validation across multiple institutions is necessary to establish generalizability.

Functional Characterization: Computational predictions should be complemented with experimental validation to establish causal relationships.

The protocols and applications described herein provide a framework for investigating ubiquitination dysregulation in cancer pathogenesis and developing clinically relevant prognostic tools. As research in this field advances, ubiquitination-related signatures are poised to become increasingly important in precision oncology approaches.

Pan-Cancer Landscape of Ubiquitination-Related Genes (URGs)

The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial post-translational modification mechanism that governs protein degradation and numerous non-proteolytic signaling pathways in eukaryotic cells [16]. Ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade mediated by ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), which collectively confer substrate specificity and facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin molecules to target proteins [17] [16]. The human genome encodes more than 600 E3 ubiquitin ligases that regulate diverse cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, DNA damage response, immune signaling, and metabolic reprogramming [17] [18]. Mounting evidence indicates that dysregulated ubiquitination pathways contribute significantly to tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance across cancer types [17] [16] [10]. This application note provides a comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of ubiquitination-related genes (URGs), detailing prognostic signatures, molecular mechanisms, and experimental protocols for investigating URGs in cancer research.

Pan-Cancer Molecular Signatures and Prognostic Models

Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures Across Cancers

Recent multi-cancer analyses have revealed conserved ubiquitination-related molecular patterns that demonstrate significant prognostic value. A comprehensive study integrating data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts of five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma) identified key nodes within the ubiquitination-modification network and established a conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) [10]. This signature effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes across all analyzed cancers and demonstrated potential for predicting immunotherapy response [10].

Table 1: Ubiquitination-Related Gene Signatures in Pan-Cancer Analysis

| Cancer Type | Key URGs Identified | Prognostic Value | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-Cancer (5 solid tumors) | URPS signature | Stratified high/low risk groups; predicted immunotherapy response | Associated with MYC pathway, oxidative phosphorylation; influenced immune cell infiltration [10] |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer | 11-URG signature | Favorable predictive ability for overall survival | Correlated with immune infiltration; all immune cells and immune-related pathways higher in low-risk group [19] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1 | Hazard Ratio = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.39–0.73 | Higher PD1/L1 expression, TMB, TNB, and TME scores in high-risk group; lower IC50 for chemotherapy drugs [11] |

| Breast Cancer | ATG5, FBXL20, DTX4, BIRC3, TRIM45, WDR78 | Significant survival differences (p < 0.05) in multiple datasets | Associated with Vd2 gd T cells and myeloid dendritic cells; linked to microbial diversity [20] |

The ubiquitination score derived from these analyses positively correlates with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma and is associated with immunotherapy resistance and poor prognosis [10]. At single-cell resolution, URPS enabled precise classification of distinct cell types and correlated with macrophage infiltration within the tumor microenvironment [10]. Functional validation revealed that the OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis plays a crucial role in modulating the MYC pathway and influencing patient prognosis [10].

Cancer-Type Specific URG Signatures

In addition to pan-cancer signatures, cancer-type specific URG models have demonstrated robust prognostic capabilities. In triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), an 11-URG signature classified patients into clusters with significantly different immune signatures and overall survival outcomes [19]. Similarly, in lung adenocarcinoma, a 4-gene ubiquitination-related risk score (URRS) based on DTL, UBE2S, CISH, and STC1 expression effectively stratified patients, with high URRS associated with worse prognosis (Hazard Ratio = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.39–0.73, p < 0.001) [11]. This signature was validated across six external cohorts and correlated with higher PD-1/PD-L1 expression, tumor mutation burden (TMB), tumor neoantigen load (TNB), and tumor microenvironment scores [11].

Molecular Mechanisms and Pathogenic Pathways

Ubiquitination in Hallmarks of Cancer

Ubiquitination regulates fundamental cancer hallmarks through diverse molecular mechanisms. E3 ubiquitin ligases function as critical regulatory nodes controlling protein abundance and activity in a timely and specific manner, with frequent deregulation observed in human cancers through genetic, epigenetic, or post-translational alterations [17]. The schematic below illustrates the ubiquitination enzyme cascade and its role in cancer-relevant pathways:

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination enzyme cascade and cancer-relevant pathways. The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade leads to substrate ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. E3 ligases specifically target cancer-relevant proteins including RTKs, p53, MYC pathway components, and immune checkpoints.

Key URG Mechanisms in Oncogenesis

Specific URGs demonstrate distinct mechanistic roles in cancer pathogenesis. UBR5, an E3 ubiquitin ligase frequently amplified in cancers, promotes tumor growth through multiple mechanisms, including AKT signaling activation, immune evasion through PD-L1 transactivation, and recruitment of immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages [21] [22]. In lung adenocarcinoma, UBR5 is overexpressed and its loss decreases cell viability, clonogenic potential, and in vivo tumor growth, accompanied by reduced AKT phosphorylation [22]. The interaction between ubiquitination and key cancer pathways extends to metabolic reprogramming, with ubiquitination scores showing enrichment in oxidative phosphorylation and MYC signaling pathways across multiple cancer types [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Constructing URG Prognostic Signatures

The establishment of ubiquitination-related prognostic models follows a standardized bioinformatics workflow that can be applied across cancer types, as illustrated below:

Diagram 2: Workflow for constructing URG prognostic signatures. The process encompasses data acquisition, pattern discovery, signature development, and clinical validation phases.

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Data Sources: Obtain RNA sequencing data and corresponding clinical information from public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and dbGaP [19] [11]. The METABRIC database is particularly valuable for breast cancer studies [19].

- URG Compilation: Curate ubiquitination-related genes from specialized databases including the Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Database (UUCD) and iUUCD 2.0, which comprehensively catalog E1, E2, E3 enzymes, and deubiquitinases [19] [11].

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize gene expression data using FPKM or TPM normalization. Remove batch effects using the ComBat function in the "sva" R package. Exclude patients with survival time less than 30 days to avoid perioperative mortality bias [19] [11].

Molecular Classification and Signature Development

- Unsupervised Clustering: Perform non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) or consensus clustering using the "ConsensusClusterPlus" R package to identify molecular subtypes based on URG expression patterns [19] [11]. Determine optimal cluster number (k) using cophenetic, dispersion, and silhouette metrics.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify differentially expressed URGs between molecular subtypes using the "limma" R package, with adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 0.8 as significance thresholds [11].

- Prognostic Gene Selection: Apply univariate Cox regression (p < 0.01), Random Survival Forests (variable importance > 0.25), and LASSO-Cox regression to identify robust prognostic URGs [19] [11]. Use 10-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal lambda value in LASSO analysis.

- Risk Score Calculation: Construct the prognostic signature using the formula: Risk score = Σ(βi × Expi), where βi represents the coefficient from multivariate Cox regression and Expi represents gene expression value [11].

Model Validation and Clinical Correlation

- Validation Cohorts: Validate the prognostic model in independent external datasets. For TNBC, the METABRIC cohort can serve as training set with GSE58812 as validation [19]. For lung adenocarcinoma, validate using multiple GEO datasets (GSE30219, GSE37745, GSE41271, GSE42127, GSE68465, GSE72094) [11].

- Survival Analysis: Assess prognostic performance using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. Evaluate predictive accuracy via time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and calculate area under the curve (AUC) values [19] [11].

- Clinical Utility Assessment: Correlate risk scores with clinicopathological features, immune cell infiltration (using CIBERSORT, MCP-counter, or ESTIMATE algorithms), tumor mutation burden, and therapy response [19] [11].

Protocol for Functional Validation of URGs

In Vitro Functional Assays

- Gene Manipulation: Perform UBR5 knockdown using shRNA or siRNA in lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (A549, H460) [22]. Use lentiviral transduction for stable knockdown and confirm efficiency via Western blotting.

- Cell Viability Assessment: Conduct cell viability assays using Alamar Blue reagent. Plate 2,000 cells per well in 96-well plates post-knockdown and measure fluorescence daily for four consecutive days [22].

- Clonogenic Assays: Seed 1,000 transfected cells in 6-well plates and culture for 10-14 days with medium changes every two days. Fix colonies with ethanol, stain with crystal violet, and count colonies exceeding 50 cells [22].

- Signaling Pathway Analysis: Analyze downstream signaling pathways (e.g., AKT, MAPK) via Western blotting following URG perturbation. Use antibodies targeting total and phosphorylated proteins (e.g., pAKT S473, total AKT) [22].

In Vivo Tumorigenesis assays

- Xenograft Models: Subcutaneously inject 1.25 × 10^5 UBR5-knockdown or control A549 cells suspended in 200μL PBS into each flank of NRGS mice (NOD/RAG1/2−/−IL2Rγ−/−) [22].

- Tumor Monitoring: Measure tumor dimensions twice weekly using calipers. Calculate tumor volume using the formula: Volume = (Length × Width^2)/2. Continue monitoring for 4-6 weeks or until tumors reach ethical endpoint size [22].

- Statistical Analysis: Compare tumor volumes between experimental groups using Wilcoxon paired t-test. Perform one-way ANOVA for multiple group comparisons in in vitro studies [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for URG Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | "sva" R package (batch effect removal), "ConsensusClusterPlus" (molecular subtyping), "glmnet" (LASSO regression), "ESTIMATE" (TME scoring) | Computational analysis of URG signatures and prognostic model development | Apply ComBat algorithm for batch correction; use 10-fold cross-validation in LASSO [19] [11] |

| Cell Line Models | A549, H460 (lung adenocarcinoma); MDA-MB-231 (TNBC); HEK293T (protein interaction studies) | Functional validation of URG mechanisms in relevant cancer contexts | Regularly authenticate cell lines by STR profiling; routinely test for mycoplasma contamination [22] |

| Antibodies | UBR5 (Bethyl, A300-573A), pAKT S473 (CST, 4060), FLAG (CST, 14793), GAPDH (Santa Cruz, sc47724) | Protein expression analysis, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting | Validate antibodies for specific applications; use appropriate loading controls [22] |

| Animal Models | NRGS mice (NOD/RAG1/2−/−IL2Rγ−/−), nude mice | In vivo tumorigenesis and therapeutic efficacy studies | Monitor tumor volumes twice weekly; adhere to ethical endpoint guidelines [22] |

| Ubiquitination Assays | Anti-K-ε-GG antibody-based enrichment, LC-MS/MS, co-immunoprecipitation | Identification of ubiquitination sites and ubiquitinated protein substrates | Use ubiquitin remnant motif analysis (A-X(1/2/3)-K*); validate findings with DUB treatments [23] |

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Implications

URG Signatures in Precision Oncology

Ubiquitination-related gene signatures demonstrate significant clinical utility in prognostication and treatment stratification. The 11-URG signature in TNBC enables patient stratification into high-risk and low-risk groups with distinct overall survival, with the low-risk group exhibiting enhanced immune cell infiltration and immune-related pathway activation [19]. Similarly, the 4-gene URRS in lung adenocarcinoma identifies patients with higher tumor mutation burden, neoantigen load, and PD-1/PD-L1 expression who may benefit from immunotherapy [11]. These signatures can be incorporated into nomograms combining risk scores with clinicopathological characteristics to enhance predictive accuracy for clinical decision-making [19].

Therapeutic Targeting of Ubiquitination Pathways

The ubiquitin-proteasome system presents promising therapeutic targets, with several clinical strategies emerging:

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib are FDA-approved for multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma, demonstrating the clinical viability of UPS targeting [16].

- Targeted Protein Degradation: Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and molecular glues represent innovative approaches that hijack the ubiquitin system to degrade disease-causing proteins [18]. These technologies enable targeting of previously "undruggable" oncoproteins and can overcome drug resistance mechanisms.

- E3 Ligase Modulation: Specific E3 ligases such as MDM2, IAPs, VHL, and CRBN are being exploited for targeted protein degradation approaches [18]. UBR5 represents a promising therapeutic target, with knockdown studies demonstrating reduced tumor growth in lung adenocarcinoma models [22].

The integration of URG signatures with therapeutic response prediction holds particular promise for immunotherapy applications. URPS demonstrates potential for identifying patients likely to benefit from immune checkpoint blockade across multiple cancer types [10]. Furthermore, ubiquitination regulates PD-L1 expression through mechanisms such as UBR5-mediated transactivation, suggesting combination therapeutic strategies that simultaneously target URGs and immune checkpoints [21].

The pan-cancer landscape of ubiquitination-related genes reveals conserved molecular patterns with significant prognostic and therapeutic implications. URG signatures consistently stratify patients across cancer types and demonstrate associations with tumor microenvironment composition, therapy response, and clinical outcomes. Standardized protocols for URG signature development and validation enable robust biomarker discovery, while functional characterization of specific URGs such as UBR5 provides mechanistic insights and reveals novel therapeutic targets. The integration of URG signatures into clinical decision-making frameworks and the development of URG-targeted therapies represent promising avenues for advancing precision oncology in the coming years.

URG Expression Patterns and Their Association with Clinical Outcomes

Ubiquitination-Related Genes (URGs) represent a critical class of molecules involved in the post-translational regulation of protein stability and function. Among these, Upregulated Gene 4 (URG4/URGCP) has emerged as a significant oncogene across multiple cancer types. This application note details the expression patterns of URG4 and its association with clinical outcomes, providing researchers with standardized protocols for evaluating URG4 as a prognostic biomarker. The content is framed within the broader context of developing ubiquitination-related gene signatures for cancer prognosis research, with particular relevance to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in oncology biomarker discovery.

Quantitative Analysis of URG4 Expression and Clinical Correlations

URG4 Expression Patterns Across Cancers

URG4 demonstrates differential overexpression in multiple malignancies compared to normal tissues. Studies have consistently shown that elevated URG4 expression correlates with advanced disease progression and poor clinical outcomes.

Table 1: URG4 Expression and Clinical Correlations in Various Cancers

| Cancer Type | Sample Size | High URG4 Expression | Key Clinical Correlations | Prognostic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric Cancer [24] | 61 patients | 37 (61%) | Significantly correlated with T stage (p<0.005) and lymphovascular invasion (p<0.005) | Significant association with 2-year survival (p<0.05) |

| Cervical Cancer [25] | 167 patients | 59 (35.13%) | Correlated with clinical stage (p<0.0001), tumor size (p=0.012), T classification (p=0.023), lymph node metastasis (p=0.001) | Shorter OS and DFS; independent prognostic factor |

| Multiple Cancers [24] [25] | Various | Varies by cancer | Associated with tumor progression, metastasis, recurrence in gastric, bladder, lung, colon, thyroid, prostate cancers, glioblastoma, neuroblastoma, leukemia | Poor survival outcomes across cancer types |

Statistical Analysis of URG4 Clinical Impact

The quantitative assessment of URG4's clinical significance involves several statistical measures that researchers should incorporate in their analyses:

Table 2: Statistical Measures for Quantitative Data Analysis in URG Studies

| Statistical Measure | Calculation Method | Application in URG Research | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Sum of observations divided by number of observations [26] | Comparing average URG4 expression levels between tumor and normal tissues | Uses all data values but vulnerable to outliers |

| Median | Middle value of ordered data [26] | Describing central tendency of URG4 expression scores | Not affected by outliers; better for skewed data |

| Standard Deviation | Square root of the average squared deviations from the mean [26] | Measuring variability in URG4 expression within patient cohorts | Useful for establishing reference intervals; vulnerable to outliers |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | Coefficient from Cox proportional hazards model | Quantifying URG4's impact on survival outcomes | Provides effect size for prognostic impact |

| p-value | Probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as observed | Determining statistical significance of URG4 correlations | Standard threshold of p<0.05 typically used |

Experimental Protocols for URG4 Analysis

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Protocol for URG4 Detection

Principle: This protocol enables the detection and semi-quantification of URG4 protein expression in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections [24] [25].

Reagents Required:

- Primary antibody: Rabbit polyclonal URG4 antibody (e.g., Abcam Cat No: 103,323)

- Secondary detection system: Avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex

- Substrate: Diaminobenzidine (DAB)

- Counterstain: Mayer's hematoxylin

- Antigen retrieval solution (e.g., citrate buffer, pH 6.0)

Procedure:

- Sectioning: Cut paraffin-embedded tumor tissue blocks at 4-micron thickness.

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration:

- Incubate slides at 60°C for 30 minutes

- Deparaffinize in xylene (3 changes, 5 minutes each)

- Rehydrate through graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70%) to distilled water

- Antigen Retrieval:

- Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0)

- Heat in microwave or pressure cooker for 10-20 minutes

- Cool slides to room temperature for 30 minutes

- Immunostaining:

- Block endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H₂O₂ for 10 minutes

- Apply primary URG4 antibody at 1:100 dilution for 60 minutes at room temperature

- Apply biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 minutes

- Apply avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex for 30 minutes

- Develop with DAB substrate for 5-10 minutes

- Counterstaining and Mounting:

- Counterstain with Mayer's hematoxylin for 1-2 minutes

- Dehydrate through graded alcohols and xylene

- Mount with permanent mounting medium

Scoring System: [24]

- Frequency of positive cells: None: 0; 1-25%: 1; 26-50%: 2; >50%: 3

- Staining intensity: None: 0; Mild: 1; Moderate: 2; Strong: 3

- Total Score: Multiply frequency and intensity scores

- Interpretation: Scores 0-4: Low URG4 expression; Scores 6-9: High URG4 expression

RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR Protocol

Principle: This protocol enables quantification of URG4 mRNA expression levels in cell lines and tissue samples [25].

Reagents Required:

- TRIzol reagent for RNA extraction

- DNase I, RNase-free

- Reverse transcription kit with random hexamers

- Quantitative PCR master mix

- URG4-specific primers:

- Sense: 5'-CGCAATCATCTCCTTCCATT-3'

- Antisense: 5'-TCCACGAAGTCCTCGTTCTC-3'

- Housekeeping gene primers (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin)

Procedure:

- RNA Extraction:

- Homogenize tissue or cells in TRIzol reagent

- Add chloroform (0.2 ml per 1 ml TRIzol) and centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Transfer aqueous phase to fresh tube

- Precipitate RNA with isopropyl alcohol, wash with 75% ethanol

- Dissolve RNA in RNase-free water

- DNA Digestion:

- Treat RNA samples with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination

- Inactivate DNase by heat treatment or EDTA

- cDNA Synthesis:

- Use 2 μg of total RNA for reverse transcription

- Incubate with random hexamers and reverse transcriptase at appropriate conditions

- Quantitative PCR:

- Prepare reaction mix with cDNA, primers, and PCR master mix

- Run amplification with following conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40 cycles of: 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute

- Calculate relative expression using 2^(-ΔΔCt) method

Statistical Analysis Protocol for Clinical Correlations

Principle: This protocol provides a standardized approach for analyzing associations between URG4 expression and clinical parameters [24] [26].

Software Requirements:

- Statistical software (e.g., R 4.2.2, SPSS, GraphPad Prism)

- Appropriate packages for survival analysis (e.g., "survival" package in R)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Code clinical parameters appropriately (e.g., T stage as ordinal variable)

- Classify URG4 expression as high/low based on predetermined cut-off

- Descriptive Statistics:

- Calculate mean, median, standard deviation for continuous variables

- Generate frequency tables for categorical variables

- Association Analysis:

- Use Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables (e.g., URG4 expression vs. lymph node status)

- Apply Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables between groups

- Survival Analysis:

- Perform Kaplan-Meier analysis for overall survival and disease-free survival

- Use log-rank test to compare survival curves between high and low URG4 groups

- Conduct univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to identify independent prognostic factors

- Interpretation:

- Consider p-value < 0.05 as statistically significant

- Report hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for Cox models

Visualization of Experimental Workflow

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for URG4 expression analysis and clinical correlation studies. The diagram illustrates the integrated approach combining laboratory techniques with clinical data analysis to validate URG4 as a prognostic biomarker.

URG4 in Cancer Signaling Pathways

Figure 2: URG4 signaling pathways in cancer progression. The diagram illustrates the molecular mechanisms through which URG4 overexpression drives tumor aggressiveness and poor clinical outcomes.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for URG4 Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/Example | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Rabbit polyclonal URG4 antibody (Abcam Cat No: 103,323) [24] | Detection of URG4 protein in IHC and Western blot | Optimal dilution 1:100 for IHC; validate specificity with controls |

| PCR Primers | URG4-specific primers: Sense 5'-CGCAATCATCTCCTTCCATT-3', Antisense 5'-TCCACGAAGTCCTCGTTCTC-3' [25] | mRNA quantification via RT-qPCR | Verify amplification efficiency; use appropriate housekeeping genes |

| RNA Extraction Kits | TRIzol reagent [25] | RNA isolation from cells and tissues | Maintain RNase-free conditions; measure RNA quality/purity |

| Statistical Software | R software (version 4.2.2 or higher) [24] | Statistical analysis and survival curves | Use "survival" package for Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses |

| Cell Lines | Cancer cell lines relevant to studied cancer type (e.g., gastric, cervical) [25] | In vitro validation studies | Authenticate cell lines regularly; monitor for contamination |

URG4 represents a promising ubiquitination-related oncogene with significant prognostic value across multiple cancer types. The standardized protocols and analytical frameworks presented in this application note provide researchers with comprehensive methodologies for investigating URG4 expression patterns and their clinical associations. The consistent correlation between high URG4 expression and poor survival outcomes highlights its potential utility as a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target. Future research should focus on validating these findings in larger prospective cohorts and elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms through which URG4 promotes tumor progression.

The Rationale for Multi-Gene URG Signatures Over Single-Gene Biomarkers

In the field of cancer prognosis research, the transition from single-gene biomarkers to multi-gene signatures represents a paradigm shift toward embracing molecular complexity. Traditional single-gene biomarkers, while valuable for specific contexts, often fail to capture the heterogeneous nature of carcinogenesis and tumor progression [27]. Ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) constitute a particularly compelling class of biomarkers, as they regulate nearly all biological processes—including DNA damage repair, cell-cycle regulation, signal transduction, and protein degradation—through the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) [27]. However, relying on individual URGs for prognostic predictions presents significant limitations, as the complex, interconnected nature of ubiquitination pathways means that no single gene can adequately represent the system's overall behavior.

Multi-gene URG signatures address this limitation by providing a more comprehensive view of the biological state. By simultaneously evaluating multiple genes, these signatures can capture pathway activity, identify robust prognostic patterns, and ultimately offer more accurate predictions of patient outcomes [27] [28]. This approach aligns with the understanding that cancer is driven by complex molecular networks rather than isolated genetic alterations.

Theoretical Foundation: Comparative Advantages of Multi-Gene Signatures

Enhanced Prognostic Accuracy and Robustness

Multi-gene signatures demonstrate superior performance in prognostic stratification compared to single-gene approaches by capturing cooperative biological effects. Where single-gene biomarkers may show variable performance across different patient populations due to tumor heterogeneity, multi-gene signatures maintain more consistent prognostic value by aggregating signals from multiple pathways [28]. This robustness is particularly evident in large-scale validation studies, where multi-gene signatures have demonstrated stable performance across diverse clinical cohorts and microarray platforms [29].

Biological Comprehensiveness

The molecular complexity of carcinogenesis involves coordinated dysregulation across multiple biological pathways. Multi-gene URG signatures can simultaneously reflect various aspects of tumor biology, including immune response, cellular stress adaptation, and metabolic reprogramming [27]. This comprehensive perspective enables more accurate patient stratification and provides insights into the underlying biological mechanisms driving disease progression.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Single-Gene vs. Multi-Gene Biomarker Approaches

| Characteristic | Single-Gene Biomarkers | Multi-Gene Signatures |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Coverage | Limited to single pathway components | Comprehensive coverage across multiple pathways |

| Prognostic Stability | Vulnerable to tumor heterogeneity | Robust across diverse populations |

| Technical Validation | Straightforward but limited | Complex but more informative |

| Clinical Utility | Often insufficient for standalone decisions | Better suited for clinical stratification |

| Mechanistic Insight | Narrow focus on specific functions | Systems-level understanding |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Gene URG Signature Development

Protocol 1: Identification and Prioritization of Ubiquitination-Related Genes

Purpose: To systematically identify differentially expressed URGs with potential prognostic significance from transcriptomic datasets.

Materials and Reagents:

- RNA sequencing data from tumor and matched normal tissues

- Ubiquitin-related gene sets from validated databases (e.g., GeneCards)

- Differential expression analysis tools (DESeq2 package)

- Functional annotation databases (GO, KEGG)

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain RNA-seq data from both tumor and normal adjacent tissues. For cervical cancer research, the TCGA-GTEx-CESC dataset provides 304 tumor and 13 normal samples [27].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using DESeq2 with threshold p-value <0.05 and \|log2Fold Change\| > 0.5 [27].

- Ubiqutination Gene Filtering: Extract a comprehensive list of ubiquitination-related genes (UbLGs) from GeneCards database using search term "Ubiquitin-like modifiers" with relevance score ≥3 [27].

- Intersection Analysis: Identify crossover genes by intersecting DEGs with UbLGs to obtain ubiquitination-related differentially expressed genes.

- Functional Enrichment: Perform GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using clusterProfiler package (p.adjust <0.05 & count >2) to identify biological processes and pathways significantly enriched in the crossover genes [27].

Technical Notes: The threshold of \|log2Fold Change\| > 0.5 represents a balance between detecting biologically relevant changes and maintaining statistical stringency. For studies requiring higher specificity, this threshold can be increased to 1.0.

Protocol 2: Prognostic Model Construction and Validation

Purpose: To develop a multi-gene risk score model and validate its prognostic performance in independent datasets.

Materials and Reagents:

- Clinical survival data matched with expression profiles

- Statistical computing environment (R Studio)

- Survival analysis packages (survival, glmnet)

- Validation datasets from GEO database

Procedure:

- Feature Selection: Subject crossover genes to univariate Cox regression analysis (p < 0.05) to identify genes with significant prognostic value [27].

- LASSO Regularization: Apply Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression to the significant genes from univariate analysis to prevent overfitting and select the most robust biomarkers [27].

- Risk Score Calculation: Construct a prognostic model using the formula: Risk score = Σ(coefi * expressioni), where coefi represents the coefficient derived from multivariate Cox regression for each gene, and expressioni represents the normalized expression value of each gene [27].

- Patient Stratification: Divide patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score or optimal cutoff determined by survival analysis.

- Model Validation: Validate the prognostic model in independent testing sets and external validation cohorts (e.g., GSE52903 for cervical cancer) using time-dependent ROC analysis for 1, 3, and 5-year survival [27].

Technical Notes: The ratio of 7:3 for training-to-testing set split provides sufficient data for model development while maintaining adequate validation power. For smaller datasets, leave-one-out cross-validation or repeated k-fold cross-validation is recommended.

Protocol 3: Immune Microenvironment and Therapeutic Response Analysis

Purpose: To characterize the tumor immune microenvironment and predict therapeutic responses based on the URG signature.

Materials and Reagents:

- Immune cell infiltration estimation algorithms (CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE, xCell)

- Immunotherapy response predictors

- Drug sensitivity databases (GDSC, CMap)

Procedure:

- Immune Infiltration Profiling: Estimate the abundance of various immune cell types in the tumor microenvironment using multiple algorithms (CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE, MCPcounter, xCell, ssGSEA) [30] [27].

- Immune Checkpoint Analysis: Compare expression of critical immune checkpoint molecules (e.g., PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4) between high-risk and low-risk groups [27].

- Drug Sensitivity Prediction: Correlate risk scores with drug sensitivity data from GDSC database to identify potential therapeutic vulnerabilities [30].

- Connectivity Mapping: Utilize Connectivity Map (CMap) approach to identify small molecules that might reverse the high-risk gene expression signature [30].

Technical Notes: Using multiple complementary algorithms for immune infiltration analysis provides a more comprehensive and reliable assessment than any single method.

Case Study: A 5-Gene URG Signature in Cervical Cancer

A recent study demonstrated the practical application of multi-gene URG signatures in cervical cancer, identifying five key biomarkers (MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, and CXCL8) through the protocols described above [27]. The risk score model constructed from these biomarkers effectively predicted patient survival rates with AUC values exceeding 0.6 for 1, 3, and 5-year survival [27]. Experimental validation using RT-qPCR confirmed that MMP1, TFRC, and CXCL8 were significantly upregulated in tumor tissues compared to normal controls [27].

Immune microenvironment analysis revealed that 12 types of immune cells—including memory B cells and M0 macrophages—as well as four immune checkpoints exhibited significant differences between the high-risk and low-risk groups defined by the URG signature [27]. This comprehensive analysis demonstrates how multi-gene URG signatures can simultaneously inform about prognosis, tumor biology, and potential therapeutic strategies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for URG Signature Development

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 Package | Differential expression analysis | Identifying ubiquitination-related DEGs |

| LASSO-Cox Model | Regularized regression | Selecting robust prognostic genes |

| CIBERSORT Algorithm | Immune cell quantification | Tumor microenvironment characterization |

| GDSC Database | Drug sensitivity resource | Predicting therapeutic response |

| clusterProfiler | Functional enrichment | Pathway analysis of signature genes |

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for URG Signature Development: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive pipeline for developing and validating multi-gene URG signatures, from initial data collection through final mechanistic insights.

Ubiquitin-Proteasome Signaling Pathway: This visualization represents the core ubiquitination machinery and its connection to critical cellular processes, highlighting how multi-gene signatures capture system-wide dynamics rather than isolated components.

The rationale for employing multi-gene URG signatures over single-gene biomarkers is firmly grounded in their ability to capture the complexity of cancer biology and provide more robust, clinically actionable prognostic information. The protocols outlined herein provide a standardized framework for developing and validating these signatures, with particular emphasis on ubiquitination-related genes that play fundamental roles in cellular regulation.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on integrating multi-omics data—including genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic information—to further enhance the predictive power of these signatures [30] [28]. Additionally, the application of advanced machine learning methods, such as the ABF-CatBoost integration described in colon cancer research [31], promises to unlock even more sophisticated pattern recognition capabilities for prognostic stratification.

As these methodologies continue to evolve, multi-gene URG signatures are poised to become increasingly integral to personalized cancer management, enabling more precise prognosis prediction and tailored therapeutic interventions across diverse cancer types.

Constructing and Applying URG Signatures: A Step-by-Step Guide

The discovery of ubiquitination-related gene (URG) signatures for cancer prognosis is fundamentally dependent on the integrated use of large-scale, publicly available databases. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and the Integrated Annotations for Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Database (IUUCD) collectively provide the essential data infrastructure for this research. These resources enable researchers to identify and validate molecular patterns linked to patient survival across various cancer types, forming the foundation for prognostic model development.

TCGA provides comprehensive multi-omics data and clinical information across numerous cancer types, serving as the primary source for initial model training and discovery. GEO complements TCGA by providing additional validation datasets from independent studies, enhancing the robustness of findings. The IUUCD serves as a specialized curated repository that defines the universe of genes involved in ubiquitination pathways, with one study utilizing 807 URGs from this database for cervical cancer analysis [32]. The synergy between these databases enables a systematic research pipeline from gene selection through model validation, firmly grounding URG signature development in large-scale genomic data.

Database Specifications and Access Protocols

Database Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Core Database Specifications for URG Prognostic Research

| Database | Primary Content | Key Features for URG Research | Access Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | RNA-seq, clinical data, mutations, survival data | Pan-cancer genomic profiles; clinical outcome data; standardized processing | GDC Data Portal (portal.gdc.cancer.gov); GDC API; TCGA-specific R packages |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Microarray and RNA-seq datasets from independent studies | Validation cohorts; platform diversity; independent patient populations | Web interface (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo); GEOquery R package; manually curated datasets |

| IUUCD (Integrated Annotations for Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Database) | Curated ubiquitination-related genes (E1, E2, E3 enzymes, deubiquitinases) | Comprehensive URG lists; functional classifications; conjugation pathway annotations | Web interface (iuucd.biocuckoo.org); downloadable gene lists |

Data Retrieval and Processing Workflows

TCGA Data Access Protocol:

- Data Identification: Access the GDC Data Portal and identify relevant cancer cohort (e.g., TCGA-CESC for cervical cancer, TCGA-HNSCC for head and neck cancer)

- Data Download: Retrieve RNA-seq data (FPKM or TPM normalized), clinical metadata, and somatic mutation data using the GDC Data Transfer Tool or API

- Data Processing: Convert gene identifiers, filter out low-expression genes, and normalize data if necessary using R/Bioconductor packages

- Clinical Data Integration: Merge expression matrices with survival data and other clinical parameters (age, stage, grade) for analysis

GEO Data Access Protocol:

- Dataset Identification: Search GEO using keywords (e.g., "cervical cancer," "expression profiling") and platform identifiers

- Data Retrieval: Download Series Matrix Files using the GEOquery R package or manually from the website

- Data Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization methods based on platform (e.g., RMA for microarray, TPM for RNA-seq)

- Batch Effect Assessment: Evaluate and correct for technical variations between different datasets when integrating multiple studies

IUUCD Gene List Curation:

- URG Compilation: Download comprehensive URG lists from IUUCD, typically containing 800-2,800 genes depending on inclusion criteria [32] [33]

- Functional Categorization: Classify genes into E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, E3 ligases, and deubiquitinating enzymes

- Custom Filtering: Apply relevance scoring when needed (e.g., GeneCards relevance score ≥5) to focus on high-confidence URGs [34]

Integrated Analytical Workflow for URG Signature Development

The development of URG prognostic signatures follows a multi-stage analytical process that integrates data from all three databases. The workflow below illustrates this comprehensive analytical pipeline:

Key Experimental Protocols in URG Signature Research

Bioinformatics and Statistical Methodology

Differential Expression Analysis Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Normalize raw count data using DESeq2 or edgeR for RNA-seq data

- Expression Filtering: Filter genes with low expression across samples (e.g., counts <10 in >90% of samples)

- Statistical Testing: Identify differentially expressed URGs using moderated t-tests (limma package) or negative binomial tests (DESeq2) with thresholds of |log2FC| > 0.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 [27]

- Result Integration: Intersect differentially expressed genes with IUUCD-derived URG lists to identify candidate prognostic genes

Consensus Clustering Protocol:

- Gene Selection: Extract expression profiles of prognosis-associated URGs identified through univariate Cox regression

- Cluster Algorithm: Apply k-means clustering with 1000 iterations using ConsensusClusterPlus R package

- Optimal Cluster Determination: Determine optimal cluster number (k) based on cumulative distribution function (CDF) curve analysis [32]

- Survival Validation: Validate clusters using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to ensure clinical relevance of molecular subtypes

WGCNA Co-expression Network Analysis:

- Network Construction: Build signed co-expression networks using blockwiseModules function in WGCNA R package

- Soft Threshold Selection: Choose appropriate soft-thresholding power (typically 9-12) based on scale-free topology fit > 0.9 [32]

- Module Identification: Identify co-expression modules using hierarchical clustering and dynamic tree cutting

- Module-Trait Association: Correlate module eigengenes with clinical traits and molecular subtypes to select hub modules for further analysis

LASSO Cox Regression Modeling:

- Variable Input: Input prognosis-associated URGs from univariate analysis (p < 0.05) into glmnet R package

- Parameter Tuning: Perform 10-fold cross-validation to identify optimal lambda (λ) value that minimizes partial likelihood deviance

- Gene Selection: Retain non-zero coefficient genes to construct parsimonious prognostic signature

- Risk Score Calculation: Compute risk score using formula: Risk Score = Σ(Coefi × Expri), where Coefi is LASSO-derived coefficient and Expri is gene expression value [32] [35]

Experimental Validation Techniques

RT-qPCR Validation Protocol:

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA from tumor and adjacent normal tissues using TRIzol reagent

- cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe 1μg RNA using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase with oligo(dT) primers

- qPCR Amplification: Perform reactions in triplicate using SYBR Green master mix on real-time PCR system

- Data Analysis: Calculate relative expression using 2^(-ΔΔCt) method with 18S rRNA or GAPDH as reference genes [27] [36]

Transwell Migration Assay Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Seed serum-starved cancer cells (e.g., HeLa) in upper chamber of 8μm transwell inserts

- Chemoattractant Application: Add complete culture medium to lower chamber as chemoattractant

- Incubation: Incubate for 24 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂

- Staining and Quantification: Fix migrated cells with methanol, stain with crystal violet, and count under microscope [32]

Western Blot Analysis Protocol:

- Protein Extraction: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors

- Protein Separation: Resolve 20-30μg protein by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes

- Antibody Incubation: Block with 5% BSA, incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., anti-USP21, anti-FBXO45) overnight at 4°C, then with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

- Detection: Visualize using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate and imaging system [35] [37]

Signaling Pathways and Biological Mechanisms

URG signatures frequently implicate specific biological pathways in cancer progression. The diagram below illustrates key pathways identified through URG prognostic signature research:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for URG Prognostic Signature Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | HeLa (cervical cancer), A2780 (ovarian cancer), HNSC lines | Functional validation of URG roles in proliferation, migration | Authenticate with STR profiling; regular mycoplasma testing |

| Antibodies | Anti-USP21, Anti-FBXO45, Anti-CDC20, Anti-UbcH10 | Protein expression validation; mechanistic studies | Validate specificity using knockdown controls |

| qPCR Reagents | SYBR Green master mix, M-MuLV reverse transcriptase | Expression validation of signature genes in tissues/cells | Normalize to reference genes (18S rRNA, GAPDH) |

| Invasion Assay Tools | Transwell chambers (8μm pore), Matrigel, crystal violet | Functional assessment of URG effects on cell migration | Use serum-free medium in upper chamber as chemoattractant control |

| Bioinformatics Tools | R packages: DESeq2, limma, WGCNA, glmnet, survival | Statistical analysis and model construction | Maintain reproducible code with version control |

The strategic integration of TCGA, GEO, and IUUCD databases provides a robust framework for developing ubiquitination-related gene signatures in cancer prognosis research. The standardized protocols outlined in this document enable researchers to move systematically from data acquisition through experimental validation, ensuring reproducible and clinically relevant findings. As ubiquitination continues to emerge as a promising therapeutic target in oncology, these data sourcing and analytical methodologies will remain fundamental to advancing our understanding of cancer biology and developing personalized treatment approaches.