Ubiquitination-Related Genes as Prognostic Biomarkers in Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly advancing field of ubiquitination-related genes (UbRGs) as prognostic biomarkers in oncology.

Ubiquitination-Related Genes as Prognostic Biomarkers in Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly advancing field of ubiquitination-related genes (UbRGs) as prognostic biomarkers in oncology. Ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, regulates protein stability and function across diverse cellular processes. Recent multi-omics studies have established that dysregulation of UbRGs significantly impacts cancer initiation, progression, and therapeutic response. This article synthesizes current methodologies for developing UbRG-based prognostic signatures, validates their predictive accuracy across multiple cancer types including laryngeal, ovarian, pancreatic, and esophageal cancers, and examines their role in shaping tumor immune microenvironments. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we provide critical insights into both the transformative potential and current challenges in translating UbRG biomarkers into clinical practice for personalized cancer treatment.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in Cancer: Molecular Foundations and Pathogenic Mechanisms

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes, from protein degradation to DNA repair and signal transduction [1]. This sophisticated enzymatic cascade involves three core components: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), which work in sequence to attach the small protein modifier ubiquitin to substrate proteins [1]. The reverse reaction, deubiquitination, is carried out by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which remove ubiquitin signals to maintain cellular homeostasis [2]. The balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination determines the fate and function of thousands of cellular proteins, and its dysregulation is implicated in numerous human diseases, particularly cancer [3] [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these core components, their experimental analysis, and their emerging roles as therapeutic targets in cancer research, fulfilling a critical need for a consolidated resource in this rapidly advancing field.

The Ubiquitination Cascade: Core Components and Mechanisms

The ubiquitination pathway represents a sophisticated regulatory system where E1, E2, and E3 enzymes function in concert to confer specificity and diversity to ubiquitin signaling [1].

The Enzymatic Cascade

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzymes): Initiation begins with E1 enzymes, which activate ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent process. Humans possess two E1 enzymes (UBA1 and UBA6) that catalyze the formation of a thioester bond between their catalytic cysteine and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [4] [3].

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes): Approximately 40 E2 enzymes in humans receive activated ubiquitin from E1 through a transthiolation reaction, forming an E2~Ub thioester intermediate [4] [3]. E2s contain a conserved ~150-amino acid ubiquitin-conjugating (UBC) catalytic core domain [4].

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligases): The ~600-1000 human E3 enzymes provide substrate specificity by recognizing target proteins and facilitating ubiquitin transfer from E2~Ub to substrate lysine residues [1] [3]. E3s are categorized into RING, HECT, and RBR families based on their mechanism of action [1].

Table 1: Core Enzymes in the Ubiquitination Machinery

| Enzyme Class | Human Genes | Core Function | Key Structural Features | Catalytic Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | 2 | Ubiquitin activation and E2 charging | Adenylation, catalytic cysteine, and UFD domains | ATP-dependent ubiquitin C-terminal adenylation, thioester formation with E1 active site cysteine |

| E2 (Conjugating) | ~40 | Ubiquitin carriage and transfer | Conserved UBC domain (~150 residues) with active site cysteine | Transthiolation: ubiquitin transfer from E1 to E2 active site cysteine |

| E3 (Ligating) | ~600-1000 | Substrate recognition and ubiquitin ligation | RING, HECT, or RBR domains | RING: Direct transfer from E2 to substrate; HECT: Forms E3~Ub intermediate before substrate transfer |

| DUBs | ~100 | Ubiquitin removal and recycling | USP, OTU, UCH, MJD, MINDY, or JAMM/MPN+ domains | Hydrolysis of isopeptide bond between ubiquitin and substrate lysine |

Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs)

DUBs constitute approximately 100 proteases categorized into six families: USP, OTU, UCH, MJD, MINDY, and JAMM [2]. These enzymes perform critical regulatory functions by reversing ubiquitination events, processing ubiquitin precursors, and maintaining free ubiquitin pools [2]. DUBs ensure the dynamic nature of ubiquitin signaling and have emerged as important players in disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer [2] [5].

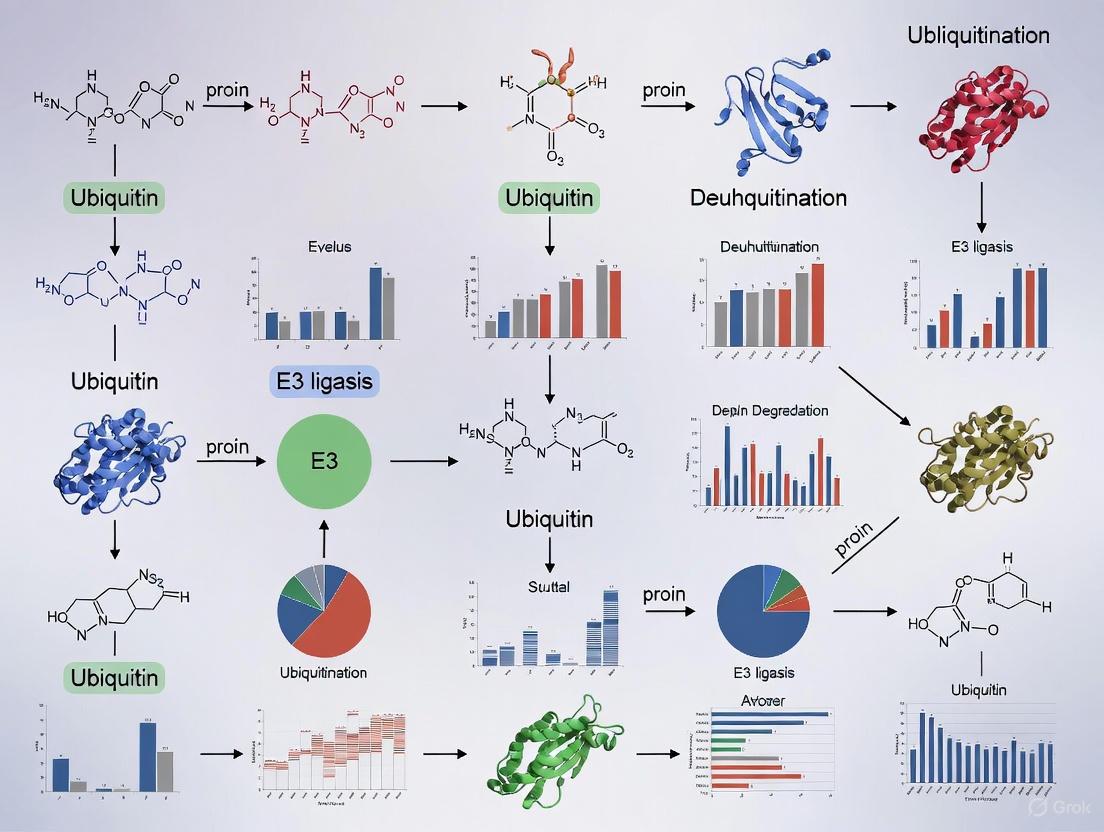

Diagram 1: The Ubiquitination Cascade and Its Reversal by DUBs. This diagram illustrates the sequential action of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes in conjugating ubiquitin to substrate proteins, and the counteracting role of DUBs in removing ubiquitin signals.

Comparative Structural and Functional Analysis

E2 Enzymes: Key Structural Determinants

E2 enzymes serve as central hubs in the ubiquitination cascade, functioning as more than simple ubiquitin carriers [4]. Their conserved UBC domain features four α-helices and a four-stranded β-sheet with an active-site cysteine preceding a short 3₁₀ helix [4]. E2 enzymes are classified into four classes:

- Class I: Contain only the UBC core domain

- Class II: Have additional N-terminal extensions

- Class III: Contain C-terminal extensions

- Class IV: Possess both N- and C-terminal extensions [3]

Critical E2 surfaces include the N-terminal helix (α1) for E1 and E3 interactions, the β2-β3 loop, and the 3₁₀-to-α2 loop [4]. The E2 backside binding site (distinct from the active site) facilitates non-covalent ubiquitin binding that can influence ubiquitin transfer and chain assembly [6].

E3 Ligases: Mechanisms of Substrate Recognition

E3 ligases employ diverse strategies for substrate recognition:

- RING E3s: Function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind E2~Ub and substrate, facilitating direct ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate [1].

- HECT E3s: Form a covalent thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to substrates [1] [7].

- RBR E3s: Utilize a hybrid mechanism incorporating aspects of both RING and HECT E3s [4].

Table 2: E2 Enzymes in Human Cancers

| E2 Enzyme | Synonyms | Regulated Targets | Relevant Cancers | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2C | UBCH10 | AKT degradation | Breast, esophageal, hepatocellular, lung, thyroid cancers [3] | Cell cycle regulation |

| UBE2T | FANCT, PIG50 | Facilitates β-catenin nuclear translocation | Breast, nasopharyngeal, bladder, hepatocellular, gastric cancers [3] | DNA damage repair, Wnt signaling |

| UBE2N | UBC13 | NF-κB and p38 signaling activation with UBE2V1/V2 | B-cell lymphoma, neuroblastoma, colon, breast cancers [3] | NF-κB signaling, DNA repair |

| UBE2S | E2-EPF | p53 degradation | Colorectal, breast, endometrial, lung, liver cancers [3] | Proteasomal degradation |

| UBE2A/B | RAD6A/B | p53 monoubiquitination, PCNA monoubiquitination | Ovarian, breast cancers, melanoma [3] | DNA damage tolerance, translation |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitination

Key Methodologies

- In Vitro Ubiquitination Assays: Reconstituted systems with purified E1, E2, E3, ubiquitin, and ATP allow direct assessment of ubiquitination activity [7]. These assays can monitor autoubiquitination, substrate ubiquitination, and free chain formation [7].

- Global Protein Stability (GPS) Profiling: A genome-wide screening strategy that identifies E3 substrates using reporter proteins fused with potential substrates [1]. Inhibiting E3 ligase activity causes substrate accumulation, revealing regulatory relationships [1].

- shRNA/CRISPR-Cas9 Screening: Functional genomic approaches to identify E3 substrates and components of ubiquitination pathways through targeted gene disruption [1].

- Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitinomics: Advanced proteomic techniques enable system-wide identification of ubiquitination sites and ubiquitin chain linkages [7].

Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Inhibitors | TAK-243 (MLN7243), PYR-41 | Inhibit ubiquitin activation | Blocks global ubiquitination; studies of ubiquitin-dependent processes |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | Nutlin-3a, Idasanutlin (RG7388) | MDM2-p53 interaction inhibitors | Stabilizes p53; studies of p53 pathway and cancer models |

| DUB Inhibitors | HBX19818, P22077 | Target USP10 | Induces anti-proliferative effects in FLT3-mutant AML |

| Molecular Glue Degraders | Mezigdomide (CC-92480), XMU-MP-8 | Induce neo-protein interactions | Targeted protein degradation; studies of oncoprotein elimination |

| SUMOylation Inhibitors | Subasumstat (TAK-981), ML-792, 2-D08 | Inhibit SUMOylation cascade | Studies of SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (StUbLs) and protein stability |

| Recombinant Proteins | E1, E2, E3 enzymes, Ubiquitin variants | Enzyme sources for in vitro assays | Reconstitute ubiquitination cascades; mechanistic studies |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Studying Ubiquitination. This workflow outlines the key steps from biochemical reconstitution to functional validation in cellular systems.

Ubiquitination Machinery in Cancer and Targeted Therapies

E2 Enzymes as Oncogenic Drivers

Dysregulation of specific E2 enzymes promotes tumorigenesis through diverse mechanisms:

- UBE2T is overexpressed in multiple cancers and facilitates β-catenin nuclear translocation while inhibiting SOX6 expression, promoting Wnt signaling activation [3].

- UBE2C promotes tumor progression through AKT degradation and is elevated in breast, esophageal, hepatocellular, and lung cancers [3].

- UBE2N partners with UBE2V1 or UBE2V2 to activate NF-κB and p38 signaling pathways, driving progression in B-cell lymphoma, neuroblastoma, and various solid tumors [3].

DUBs in Cancer Pathogenesis

DUBs demonstrate context-dependent roles in cancer, functioning as both tumor promoters and suppressors:

- USP9X exhibits dual functions in pancreatic cancer—promoting tumor cell survival in human models while acting as a suppressor in mouse models [2].

- USP22 is recognized as a cancer stem cell marker that promotes PDAC proliferation by regulating DYRK1A and PTEN-MDM2-p53 signaling [2].

- USP21 promotes PDAC growth by activating mTOR signaling and inducing micropinocytosis to support amino acid sustainability [2].

- BAP1 mutations lead to a hereditary cancer syndrome predisposing to mesothelioma, melanoma, breast cancer, and renal carcinoma [2].

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Novel approaches targeting the ubiquitination machinery show significant promise:

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Bortezomib and related compounds disrupt protein degradation, but their application is limited by non-specific effects [1].

- SUMO-Targeted Ubiquitin Ligases (StUbLs): Drugs like arsenic trioxide and fulvestrant leverage SUMO-primed ubiquitination to inactivate oncogenic fusion proteins like PML-RARα and estrogen receptor α [8].

- Molecular Glue Degraders: Compounds such as Mezigdomide (CC-92480) redirect E3 ligases to target oncoproteins for degradation [9].

- HUWE1-Targeting Compounds: BI8622 and BI8626 represent early-stage inhibitors that surprisingly function as HUWE1 substrates themselves, being ubiquitinated by their target ligase [7].

The ubiquitination machinery represents a sophisticated regulatory network with profound implications for cancer biology and therapeutics. While E3 ligases have traditionally received the most attention, recent research highlights the critical functions of E2 enzymes in determining ubiquitin chain topology and the context-dependent roles of DUBs in maintaining protein homeostasis. The experimental approaches outlined here—from in vitro ubiquitination assays to genome-wide screening strategies—provide powerful tools for deciphering the complexities of this system. As our understanding of ubiquitination deepens, new therapeutic opportunities continue to emerge, particularly through targeted protein degradation strategies and selective inhibition of specific pathway components. Future research will likely focus on developing more specific modulators of E2 and E3 activities and elucidating the complex regulatory networks that coordinate ubiquitin signaling in both normal physiology and disease states.

Ubiquitination, once recognized primarily as a mechanism for targeting proteins to the proteasome for degradation, is now understood to be a versatile post-translational modification with profound regulatory functions across cellular signaling and immune responses. This modification involves the sequential action of E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes that attach ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, creating a complex code that determines protein fate and function [10] [11]. Beyond the traditional K48-linked polyubiquitin chains that signal proteasomal degradation, atypical ubiquitin linkages—including K63, M1, K11, K27, and K29 chains—orchestrate diverse non-proteolytic processes such as signal transduction, protein trafficking, inflammation, and immune cell differentiation [12] [11]. The emerging paradigm recognizes ubiquitination as a central regulatory mechanism in immunity and cancer, with E3 ligases and deubiquitinases (DUBs) acting as precise molecular switches that control pathway activation, immune cell polarization, and cellular homeostasis. This review examines the expanding landscape of non-degradative ubiquitination, its implications for immune regulation and cancer progression, and the prognostic value of ubiquitination-related genes in clinical oncology.

Mechanistic Insights: Ubiquitination in Signaling and Immunity

Regulation of Immune Cell Function through Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination plays a critical role in fine-tuning immune responses by modulating key signaling pathways in various immune cell types. In regulatory T cells (Tregs), which are essential for maintaining immune tolerance, the E3 ligase GRAIL (RNF128) regulates IL-2 receptor signaling through a sophisticated mechanism involving competitive mono-ubiquitination [13] [10]. GRAIL mono-ubiquitinates Lys724 on cullin-5 (CUL5), thereby blocking neddylation—a ubiquitin-like modification required for activation of the CRL5 E3 ligase complex. When active, CRL5 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of phosphorylated JAK1 (pJAK1), leading to desensitization of IL-2R signaling and impaired STAT5 phosphorylation, which is crucial for Treg suppressive function [13] [10]. In autoimmune conditions, diminished GRAIL expression disrupts this balance, resulting in excessive CRL5-mediated desensitization of IL-2R signaling and compromised Treg function. Pharmacological inhibition of neddylation has demonstrated potential in restoring IL-2R signaling and Treg suppressive capacity, highlighting the therapeutic relevance of this regulatory axis [13].

In macrophages, ubiquitination governs functional plasticity and polarization states along the pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 spectrum. Multiple E3 ligases and DUBs regulate key inflammatory pathways including NF-κB, NLRP3 inflammasome assembly, and metabolic reprogramming [11]. The E3 ligases Cbl-b and Itch, along with GRAIL, dampen inflammatory signaling by targeting adaptor proteins like MyD88 and TRIF, thereby preventing excessive M1 polarization [11]. Conversely, the deubiquitinase BRCC3 removes inhibitory ubiquitin chains from NLRP3, facilitating inflammasome assembly and IL-1β maturation [11]. OTULIN, a linear linkage-specific deubiquitinase, hydrolyzes M1-linked ubiquitin chains generated by the LUBAC complex on components of TLR and TNF signaling pathways; its deficiency leads to uncontrolled NF-κB activation and severe autoinflammation [12] [11]. This intricate balance of ubiquitin ligases and DUBs allows macrophages to dynamically adjust their functional state in response to environmental cues.

Table 1: Key E3 Ubiquitin Ligases and Deubiquitinases in Immune Regulation

| Enzyme | Type | Immune Cell/Process | Mechanism of Action | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRAIL (RNF128) | E3 Ligase (RING-type) | Regulatory T Cells | Mono-ubiquitinates CUL5 at Lys724 to block CRL5 neddylation | Sustains IL-2R signaling and Treg suppressive function [13] [10] |

| CRL5 Complex | E3 Ligase (Cullin-RING) | Cytokine Signaling | Neddylation-dependent ubiquitination of pJAK1 | Desensitizes IL-2R signaling [13] |

| Cbl-b | E3 Ligase | Macrophages, T Cells | Ubiquitinates MyD88 and TRIF adaptor proteins | Terminates TLR signaling; prevents excessive M1 polarization [11] |

| OTULIN | Deubiquitinase (Linear linkage-specific) | Macrophage Inflammation | Hydrolyzes M1-linked ubiquitin chains on TLR/TNF pathway components | Restrains NF-κB activation; deficiency causes autoinflammation [12] [11] |

| BRCC3 | Deubiquitinase | Macrophage Inflammasome | Removes K48/K63 ubiquitin from NLRP3 | Promotes NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and IL-1β maturation [11] |

Ubiquitination in Inflammatory Signaling Pathways

The NF-κB pathway exemplifies how ubiquitination extends beyond protein degradation to directly activate signaling cascades. Upon stimulation of toll-like receptors (TLRs) or cytokine receptors, K63-linked and linear M1-linked polyubiquitin chains serve as essential scaffolds for signal propagation [12]. TLR activation recruits the adaptors MyD88 and IRAK1/4, leading to TRAF6 ubiquitination with K63 chains in cooperation with the E2 enzyme Ubc13. These non-degradative ubiquitin modifications create docking platforms that recruit downstream kinases like TAK1, initiating the NF-κB activation program [12]. Similarly, TNF receptor stimulation engages the LUBAC complex, which extends K63 ubiquitination on NEMO with linear M1 chains, recruiting the IKK complex and culminating in IκBα phosphorylation, K48-linked ubiquitination, and degradation—releasing NF-κB dimers to translocate to the nucleus and drive transcription of inflammatory genes [12] [14].

The NLRP3 inflammasome, responsible for caspase-1 activation and IL-1β maturation, is similarly regulated by ubiquitination. The E3 ligase HUWE1 modifies NLRP3 with atypical K27-linked chains to regulate inflammasome activity, while BRCC3-mediated deubiquitination removes degradative ubiquitin marks, permitting NLRP3 oligomerization and inflammasome assembly [12] [11]. These examples illustrate how the ubiquitin code—comprising different chain types and linkages—functions as a sophisticated language that coordinates inflammatory responses without necessarily targeting components for destruction.

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin-dependent NF-κB activation. Multiple ubiquitin linkage types (K63, M1, K48) coordinate signaling through TLR4 and TNF receptors, culminating in NF-κB nuclear translocation and inflammatory gene transcription.

Prognostic Value of Ubiquitination-Related Genes in Cancer

Ubiquitination-Based Prognostic Signatures Across Cancers

The dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways has emerged as a significant factor in cancer progression and patient outcomes. Comprehensive bioinformatics analyses have identified ubiquitination-related gene signatures with robust prognostic value across diverse malignancies. In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a three-gene ubiquitination signature comprising CDC34, FZR1, and OTULIN effectively stratifies patients into distinct risk categories [15]. Elevated expression of CDC34 and FZR1 coupled with low OTULIN expression correlates with poor prognosis, with significant differences in immune scores and drug sensitivity observed between high- and low-risk groups [15]. Similarly, in cervical cancer, a five-gene signature (MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, and CXCL8) demonstrates strong predictive value for patient survival, with the risk score model showing area under the curve (AUC) values >0.6 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival [16]. Immune microenvironment analysis revealed significant differences in 12 immune cell types between risk groups, including memory B cells and M0 macrophages, along with differential expression of four immune checkpoints [16].

Ovarian cancer studies have identified a 17-gene ubiquitination-based prognostic signature that effectively stratifies patients by overall survival [17]. The high-risk group showed significantly lower survival probability (P < 0.05), with the model achieving AUC values of 0.703, 0.704, and 0.705 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival, respectively [17]. Immune infiltration analysis demonstrated higher levels of CD8+ T cells (P < 0.05), M1 macrophages (P < 0.01), and follicular helper cells (P < 0.05) in the low-risk group, while high-risk patients exhibited more frequent mutations in MUC17 and LRRK2 genes [17]. Functional validation identified FBXO45 as a key E3 ubiquitin ligase promoting ovarian cancer growth, spread, and migration via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [17].

Table 2: Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures in Cancer

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination-Related Genes | Prognostic Value | Immune Microenvironment Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) | CDC34, FZR1, OTULIN | Elevated CDC34/FZR1 + low OTULIN = poor prognosis [15] | Significant differences in immune scores between risk groups; correlation with T-cell infiltration and endocytosis [15] |

| Cervical Cancer | MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, CXCL8 | AUC >0.6 for 1/3/5-year survival [16] | 12 immune cell types differentially abundant (including memory B cells, M0 macrophages); 4 immune checkpoints differentially expressed [16] |

| Ovarian Cancer | 17-gene signature including FBXO45 | 1-year AUC=0.703, 3-year AUC=0.704, 5-year AUC=0.705 [17] | Low-risk group: higher CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages, follicular helper cells; different mutation profiles [17] |

| Pan-Cancer | UBE2T, UBD | Overexpression correlates with poor survival across multiple cancers [18] [19] | Correlation with immune infiltration, checkpoint expression, TMB, MSI, and neoantigens [18] [19] |

Pan-Cancer Analysis of Ubiquitination Enzymes

Comprehensive pan-cancer analyses reveal that specific ubiquitination enzymes demonstrate consistent prognostic value across diverse cancer types. Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T (UBE2T) shows elevated expression in multiple tumors, where its upregulation associates with poor clinical outcomes [18]. Genetic variation analysis identifies "amplification" as the predominant alteration in UBE2T, followed by mutations, with copy number variations occurring frequently across pan-cancer cohorts [18]. UBE2T expression correlates with sensitivity to targeted agents including trametinib and selumetinib, while showing negative correlation with CD-437 and mitomycin sensitivity. Functional enrichment analyses implicate UBE2T in cell cycle regulation, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, p53 signaling, and mismatch repair pathways [18].

Similarly, ubiquitin D (UBD) demonstrates overexpression in 29 cancer types, where it associates with poor prognosis and higher histological grades [19]. Gene amplification represents the most common genetic alteration, with patients harboring these alterations exhibiting significantly reduced overall survival rates. Epigenetically, 16 cancer types show reduced UBD promoter methylation, potentially contributing to its overexpression [19]. UBD expression significantly correlates with tumor microenvironment features including immune infiltration, checkpoint expression, microsatellite instability (MSI), tumor mutational burden (TMB), and neoantigen load. Pathway analyses indicate UBD involvement in neurodegeneration, proteolysis, and apoptosis, with additional roles in NF-κB, Wnt, and SMAD2 signaling through interactions with MAD2, p53, and β-catenin [19].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Bioinformatics Pipelines for Ubiquitination Signature Development

The development of ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures follows standardized bioinformatics workflows that integrate multi-omics data. Typical pipelines begin with differential gene expression analysis between tumor and normal tissues using packages such as DESeq2 or limma, with filtering criteria generally set at fold change >2 and false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05 [15] [16]. Ubiquitination-related genes are identified from databases such as the Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Database (UUCD), which catalogs E1, E2, and E3 enzymes [17]. Survival-associated ubiquitination genes are selected through univariate Cox regression analysis, followed by least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression to identify the most prognostic genes using the glmnet package with 10-fold cross-validation [15] [16].

Risk scores are calculated using the formula: Risk score = Σ(Coefi × Expri), where Coefi represents the regression coefficient from multivariate Cox regression and Expri denotes the expression level of each gene [16] [17]. Patients are stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on the median risk score, with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank tests employed to evaluate prognostic performance. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves at 1, 3, and 5 years assess predictive accuracy, with AUC values >0.6 generally considered clinically informative [16] [17]. Additional validation typically includes independent prognostic analysis through univariate and multivariate Cox regression, immune microenvironment assessment using tools such as CIBERSORT or ESTIMATE, and drug sensitivity analysis with packages like oncoPredict to calculate half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values [15] [16].

Diagram 2: Bioinformatics workflow for developing ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures. The pipeline integrates multi-omics data to identify, validate, and apply ubiquitination-based biomarkers across cancer types.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 / limma | Bioinformatics Package | Differential gene expression analysis | Bioconductor [15] [16] |

| UUCD Database | Ubiquitin Enzyme Database | Comprehensive catalog of E1, E2, E3 enzymes | http://uucd.biocuckoo.org/ [17] |

| glmnet | Bioinformatics Package | LASSO Cox regression analysis | CRAN [15] [16] |

| CIBERSORT | Computational Tool | Immune cell infiltration analysis | https://cibersort.stanford.edu/ [15] [16] |

| oncoPredict | R Package | Drug sensitivity analysis (IC50 calculation) | Bioconductor [15] |

| TCGA/GTEx | Databases | Transcriptomic and clinical data | https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga [17] [18] [19] |

| GEPIA2 | Web Tool | Gene expression analysis and visualization | http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/ [18] [19] |

| cBioPortal | Web Resource | Cancer genomics and visualization | https://www.cbioportal.org/ [18] [19] |

| Neddylation Inhibitors (NAEi) | Small Molecules | Pharmacological inhibition of neddylation pathway | Research compounds [13] [10] |

| PROTACs | Therapeutic Modality | Targeted protein degradation via ubiquitin-proteasome system | Clinical development [17] |

The expanding landscape of ubiquitination research reveals an intricate regulatory system that extends far beyond its traditional role in protein degradation to encompass sophisticated control of immune signaling, cell fate decisions, and cancer progression. Non-degradative ubiquitin linkages, particularly K63 and M1 chains, serve as critical signaling scaffolds in inflammation and immunity, while the balanced expression of E3 ligases and deubiquitinases maintains immune homeostasis. In clinical oncology, ubiquitination-related genes demonstrate remarkable prognostic value across diverse malignancies, with multi-gene signatures effectively stratifying patients by survival outcomes, immune microenvironment composition, and therapeutic vulnerabilities. The integration of bioinformatics approaches with experimental validation has accelerated the discovery of ubiquitination-based biomarkers, while emerging therapeutic strategies—including neddylation pathway inhibitors and PROTAC technology—hold significant promise for targeting the ubiquitin system in cancer and immune disorders. As our understanding of the ubiquitin code continues to evolve, so too will opportunities for diagnostic innovation and therapeutic intervention across the spectrum of human disease.

Mechanisms of Ubiquitination Dysregulation in Carcinogenesis

Ubiquitination, a pivotal post-translational modification, is a highly specific process involving the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins, thereby regulating their stability, localization, and activity [20] [21]. This enzymatic cascade is mediated by ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes, with E3 ligases providing substrate specificity [22] [20]. The dysregulation of this system contributes significantly to tumorigenesis by affecting critical cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA repair, apoptosis, and immune surveillance [20] [23] [21]. This review objectively compares the prognostic value of ubiquitination-related genes across multiple cancer types, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to establish their utility in cancer research and drug development.

Ubiquitination Machinery and Cancer-Associated Alterations

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) comprises approximately 2 E1 enzymes, 40 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases in human cells, along with deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that reverse the process [22] [20]. These components collectively maintain protein homeostasis, and their dysfunction can lead to carcinogenesis through multiple mechanisms. E3 ligases, in particular, demonstrate remarkable substrate specificity, making them attractive therapeutic targets [20]. Oncogenic alterations in the UPS include mutations in E3 ligase genes leading to accelerated degradation of tumor suppressors, overexpression of specific E2 enzymes driving cell cycle progression, and aberrant DUB activity stabilizing oncoproteins [22] [20] [21].

Different ubiquitination linkage types dictate distinct functional outcomes for substrate proteins. While K48-linked polyubiquitination typically targets proteins for proteasomal degradation, K63-linked chains often regulate protein activity and subcellular localization [22] [24]. Monoubiquitination plays roles in DNA damage repair and histone modification, with recent evidence implicating it in cancer immune evasion [21]. The complexity of the ubiquitin code—encompassing chain topology, length, and modification types—creates a sophisticated regulatory layer that is frequently disrupted in cancer [20] [21].

Table 1: Ubiquitination Linkage Types and Their Roles in Cancer

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Role in Cancer | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Targets proteins for proteasomal degradation | Accumulation of oncoproteins; loss of tumor suppressors | p53 degradation by MDM2 [22] [20] |

| K63 | Regulates activity, localization, and signaling | Activation of oncogenic signaling pathways | β-catenin stabilization [22] |

| K11 | Cell cycle regulation and trafficking | Dysregulated cell cycle progression in cancer | APC/C-mediated cyclin degradation [22] [20] |

| K27 | Mitochondrial autophagy | Impaired cellular homeostasis | Parkin-mediated mitophagy [20] |

| K6 | DNA damage repair | Genomic instability | RNF168-mediated DNA repair [25] [20] |

| M1 (Linear) | NF-κB activation | Inflammation and cancer progression | LUBAC complex in lymphoma [21] |

| Monoubiquitination | Histone modification, endocytosis | Altered gene expression, immune evasion | PD-L1 internalization [21] |

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Models Across Cancers

Recent research has established ubiquitination-related gene signatures as powerful prognostic tools across diverse malignancies. These models typically employ bioinformatic analyses of public datasets (e.g., TCGA, GEO) to identify ubiquitination-related genes with significant associations with patient survival, which are then incorporated into risk stratification systems.

Ovarian Cancer

In ovarian cancer, a 17-gene ubiquitination-related signature effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with significantly different overall survival (p < 0.05) [25]. The model demonstrated high prognostic accuracy with area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.703, 0.704, and 0.705 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival, respectively [25]. The high-risk group exhibited distinct immune profiles with lower levels of CD8+ T cells (p < 0.05), M1 macrophages (p < 0.01), and follicular helper T cells (p < 0.05), along with higher mutation frequencies in MUC17 and LRRK2 genes [25]. Experimental validation identified FBXO45 as a key E3 ubiquitin ligase promoting ovarian cancer growth, spread, and migration via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [25].

Lung Adenocarcinoma

A four-gene ubiquitination-related risk score (URRS) comprising DTL, UBE2S, CISH, and STC1 effectively predicted prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) [26]. Patients with higher URRS had significantly worse outcomes (Hazard Ratio [HR] = 0.54, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.39–0.73, p < 0.001), a finding validated across six external cohorts (HR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.36–0.93, pmax = 0.023) [26]. The high URRS group showed higher PD-1/PD-L1 expression (p < 0.05), increased tumor mutation burden (TMB, p < 0.001), elevated tumor neoantigen load (TNB, p < 0.001), and distinct tumor microenvironment scores (p < 0.001) [26]. Upregulation of STC1, UBE2S, and DTL was associated with poorer prognosis, while CISH upregulation correlated with better outcomes [26].

Breast Cancer

A six-gene ubiquitination signature (ATG5, FBXL20, DTX4, BIRC3, TRIM45, and WDR78) demonstrated robust prognostic power in breast cancer [27]. This signature was validated across multiple external datasets (TCGA-BRAC, GSE1456, GSE16446, GSE20711, GSE58812, and GSE96058), with Kaplan-Meier curves showing significant survival differences (p < 0.05) [27]. Single-cell analysis revealed distinct immune compositions between risk groups, with Vd2 γδ T cells less abundant in the low-risk group and myeloid dendritic cells absent in the high-risk group [27]. Tumor microbiological analysis further identified notable variations in microorganism diversity between risk groups [27].

Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

In ESCC, researchers identified five key ubiquitination-related genes (BUB1B, CHEK1, DNMT1, IRAK1, and PRKDC) with significant prognostic value through analysis of TCGA-ESCC, GSE20347, and in-house datasets [28]. These genes play crucial roles in cell cycle regulation and immune responses, with functional enrichment analyses linking them to ESCC pathogenesis [28]. The study highlighted these genes as promising biomarkers and therapeutic targets for a cancer type with a 5-year survival rate below 20% [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Models Across Cancers

| Cancer Type | Key Genes in Signature | HR (High vs. Low Risk) | Validation Approach | Clinical/Biological Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian Cancer | 17-gene signature | Significant (p < 0.05) [25] | External datasets (GSE165808, GSE26712) [25] | Altered immune infiltration (CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages); FBXO45/Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation [25] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1 | 0.54 (95% CI: 0.39-0.73) [26] | 6 external GEO datasets [26] | Higher PD-1/PD-L1, TMB, TNB; distinct TME [26] |

| Breast Cancer | ATG5, FBXL20, DTX4, BIRC3, TRIM45, WDR78 | Significant (p < 0.05) [27] | 6 external datasets [27] | Altered immune cell composition (Vd2 γδ T cells, dendritic cells); microbial diversity [27] |

| Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma | BUB1B, CHEK1, DNMT1, IRAK1, PRKDC | Significant (p < 0.05) [28] | TCGA, GSE20347, in-house data [28] | Cell cycle and immune response pathways [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Research

Prognostic Model Development Workflow

The development of ubiquitination-related prognostic models follows a systematic bioinformatics pipeline [25] [26] [28]:

Data Collection and Preprocessing: Transcriptomic data and clinical information are obtained from public databases (TCGA, GEO). Normalization and batch effect correction are applied using tools like the "limma" R package [25] [26] [28].

Ubiquitination-Related Gene Selection: URGs are compiled from databases such as iUUCD 2.0 and UUCD, typically including E1, E2, and E3 enzymes [25] [26].

Differential Expression Analysis: Differentially expressed URGs between tumor and normal tissues are identified using |logFC| ≥ 0.5-1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 as thresholds [25] [28].

Prognostic Gene Selection: Univariate Cox regression, LASSO regression, and Random Survival Forests are applied to identify URGs with significant survival associations [25] [26].

Risk Model Construction: A risk score formula is developed: Risk score = Σ(Coefi × Expri), where Coefi is the regression coefficient and Expri is the gene expression level [25] [26].

Validation: Models are validated using internal cross-validation and external independent datasets, assessing performance via Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, ROC curves, and AUC values [25] [26] [27].

Diagram 1: FBXO45 promotes ovarian cancer progression via Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Based on experimental validation in ovarian cancer [25].

Functional Validation Experiments

Beyond bioinformatic analyses, functional experiments are crucial for validating the mechanistic roles of ubiquitination factors:

Gene Manipulation in Cell Lines:

Phenotypic Assays:

Molecular Mechanism Studies:

Immunological Analyses:

Key Signaling Pathways in Ubiquitination-Mediated Carcinogenesis

Regulation of Immune Checkpoints

The ubiquitin-proteasome system plays a crucial role in regulating PD-1/PD-L1 stability, thereby influencing tumor immune evasion [24]. Multiple E3 ligases target PD-L1 for degradation, including SPOP which promotes PD-L1 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation in colorectal cancer [24]. Conversely, competitive binding partners such as ALDH2 and SGLT2 can inhibit SPOP-mediated PD-L1 degradation, stabilizing PD-L1 and promoting immune escape [24]. The small-molecule SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin can disrupt SGLT2-PD-L1 interaction, restoring SPOP-mediated PD-L1 degradation and enhancing T cell antitumor activity [24]. Additional regulatory mechanisms include CDK4-mediated phosphorylation of SPOP, which promotes 14-3-3γ binding and impairs SPOP's tumor suppressor function [24].

Diagram 2: UPS regulation of PD-L1 stability impacts tumor immune evasion. Based on mechanism described in review [24].

Oncoprotein and Tumor Suppressor Regulation

Ubiquitination critically regulates key oncoproteins and tumor suppressors:

- p53: The E3 ligase MDM2 binds to p53, promoting its ubiquitination and degradation; MDM2 overexpression is observed in various cancers [22] [20].

- RAS proteins: Ubiquitination dynamically regulates RAS stability, membrane localization, and signaling, with heterogeneity across different RAS isoforms (KRAS4A, KRAS4B, NRAS, HRAS) [29].

- β-catenin: K11-linked polyubiquitination can stabilize β-catenin in colorectal cancer cells, contrary to the typical degradation signal [22].

- c-Myc: Multiple E3 ligases including FBXW7 regulate c-Myc stability, with dysregulation contributing to sustained oncogenic signaling [20].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Reagents | DMEM, RPMI 1640, Fetal Bovine Serum | Cell line maintenance and experiments | Ovarian cancer cell culture (A2780, HEY) [25] |

| Molecular Biology Kits | RNAiso Reagent, RNA Reverse Transcription Kit, Real-time PCR Kit | Gene expression analysis | Validation of ubiquitination-related gene expression [25] [26] |

| Transfection Reagents | Lipo2000 | Nucleic acid delivery for gene modulation | FBXO45 functional studies in ovarian cancer [25] |

| Protein Analysis Reagents | High-performance RIPA lysate, Phosphatase/Protease Inhibitor Mix, ECL Chemiluminescent Liquid | Protein extraction and detection | Western blot analysis of ubiquitination pathways [25] |

| Antibodies | FBXO45, WNT1, β-cadherin, c-Myc, GAPDH | Target protein detection | Pathway validation in ovarian cancer [25] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, Ixazomib | Clinical targeting of UPS | Multiple cancer types [20] |

| E1-Targeting Compounds | MLN7243, MLN4924 | Experimental inhibition of ubiquitination cascade | Preclinical cancer models [20] |

| E2-Targeting Compounds | Leucettamol A, CC0651 | Selective E2 enzyme inhibition | Preclinical studies [20] |

| E3-Targeting Compounds | Nutlin, MI-219 (MDM2 inhibitors) | Specific E3 ligase modulation | p53 stabilization approaches [20] |

| DUB Inhibitors | Compounds G5, F6 | Deubiquitinase inhibition | Experimental therapeutic strategy [20] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system has yielded significant clinical successes, particularly with proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib in multiple myeloma [20]. Emerging strategies include:

- PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras): Bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target specific proteins for degradation; several are in clinical trials including ARV-110 and ARV-471 [25] [21].

- Molecular Glues: Small molecules that enhance interaction between E3 ligases and target proteins; examples include CC-90009 in clinical trials for leukemia [21].

- Specific E3 Ligase Modulators: Compounds like indomethacin enhance SYVN1-mediated ITGAV ubiquitination in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, while honokiol induces KRT18 ubiquitination in melanoma [21].

The prognostic models based on ubiquitination-related genes not only stratify patient risk but also inform treatment selection. High-risk lung adenocarcinoma patients with elevated URRS showed lower IC50 values for various chemotherapy drugs, suggesting increased susceptibility [26]. Similarly, the integration of ubiquitination signatures with immune profiling may guide immunotherapy approaches, particularly given the role of UPS in regulating PD-1/PD-L1 [24].

Future research directions should focus on validating these prognostic models in prospective clinical trials, developing isoform-specific ubiquitination modulators, and exploring combination therapies targeting both ubiquitination pathways and conventional oncogenic drivers. The heterogeneity of ubiquitination patterns across cancer types and even within specific molecular subtypes necessitates personalized approaches based on comprehensive ubiquitination profiling.

Comprehensive Databases for Ubiquitination-Related Gene Discovery

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates protein stability, function, and localization, thereby influencing nearly all cellular processes in eukaryotic cells. This sophisticated process involves a cascade of enzymes: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), ubiquitin ligases (E3), and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [16] [30]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) degrades approximately 80% of intracellular proteins, maintaining genomic stability and modulating signaling pathways to regulate critical processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, DNA damage repair, and immune responses [16]. Given its fundamental role in cellular homeostasis, dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways is intimately associated with various diseases, particularly cancer. Recent studies have demonstrated that abnormalities in ubiquitination-related genes are closely linked to numerous cancers including cervical cancer [16], esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [28], lung adenocarcinoma [26], ovarian cancer [17], and acute myeloid leukemia [31]. The growing recognition of ubiquitination's pathological significance has accelerated the need for comprehensive databases that facilitate the systematic discovery and analysis of ubiquitination-related genes, particularly for developing prognostic models and targeted therapies in oncology.

Comprehensive Database Comparison

Researchers have access to several specialized databases that catalog ubiquitination-related genes and enzymes. These resources vary in scope, content, and functionality, making each suitable for different research applications. The table below provides a detailed comparison of major databases used in contemporary ubiquitination research.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Ubiquitination-Related Gene Databases

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Number of Genes | Gene Categories | Key Features | Use Cases in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iUUCD 2.0 [26] | Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like conjugation | 966 genes | E1, E2, E3 enzymes | Comprehensive coverage of ubiquitination enzymes; regularly updated | Identification of prognostic signatures in lung adenocarcinoma [26] |

| UUCD [17] | Ubiquitinating enzymes | 929 genes | E1 (8), E2 (39), E3 (882) | Categorized by enzyme type; established resource | Development of ovarian cancer risk models [17] |

| GeneCards [16] [28] | Integrated human genes | 465 ubiquitination-related genes (score ≥3) [16]; 1,274 URGs (score >5) [28] | Various ubiquitination-related categories | Relevance scoring system; integrates multiple data sources | Screening ubiquitination-related differentially expressed genes [16] [28] |

| Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [28] | Annotated gene sets | 542 ubiquitination-related genes | Gene sets related to ubiquitination | Collection of biologically defined gene sets | Functional enrichment analysis [28] |

The selection of an appropriate database depends heavily on research objectives. For studies focused specifically on ubiquitination enzymes, iUUCD 2.0 and UUCD offer specialized curation. For broader investigations that include ubiquitination-related cellular components and processes, GeneCards provides a more comprehensive resource with relevance scoring to prioritize genes [16] [28]. The Molecular Signatures Database is particularly valuable for pathway analysis and gene set enrichment studies [28]. Each database has been instrumental in various cancer research contexts, enabling the identification of prognostic biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets across multiple cancer types.

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination-Related Gene Analysis

Standardized Workflow for Prognostic Model Development

Research into ubiquitination-related genes typically follows a systematic workflow that integrates bioinformatics analysis with experimental validation. The standard methodology encompasses data acquisition, differential expression analysis, prognostic model construction, and experimental validation, as exemplified by studies in cervical cancer [16], lung adenocarcinoma [26], and ovarian cancer [17]. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive research workflow:

Diagram 1: Research workflow for ubiquitination-related gene discovery

Detailed Methodologies for Key Analytical Steps

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Research typically begins with acquiring transcriptomic data from public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) [16] [26]. For example, in lung adenocarcinoma research, the TCGA-LUAD cohort serves as the primary training set, while multiple GEO datasets (GSE30219, GSE37745, GSE41271, GSE42127, GSE68465, and GSE72094) provide validation cohorts [26]. Similar approaches are employed in cervical cancer studies using TCGA-GTEx-CESC datasets [16] and in ovarian cancer research combining TCGA-OV and GTEx data [17]. Quality control measures include removing samples with survival times fewer than 3 months, excluding formalin-fixed samples, and filtering recurrent tissues to ensure data integrity [26]. Normalization procedures vary by platform, with microarray data typically processed using the "limma" R package [28] [26] and RNA-seq data analyzed with DESeq2 [16] or edgeR [17].

Identification of Ubiquitination-Related Differentially Expressed Genes

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between tumor and normal tissues are identified using established thresholds (typically |log2Fold Change| > 0.5-1.0 and adjusted p-value < 0.05) [16] [17]. These DEGs are then intersected with ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) obtained from specialized databases to identify ubiquitination-related differentially expressed genes (UbDEGs). For instance, in Crohn's disease research, investigators identified 32 UbDEGs by intersecting DEGs from the GSE95095 dataset with ubiquitination-related genes from GeneCards with a relevance score >10 [32]. In tuberculosis research, 96 UbDEGs were identified using similar methodology [33]. Functional enrichment analysis of these UbDEGs using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways typically reveals their involvement in critical processes including cell cycle regulation, immune response, and protein catabolism [16] [28] [33].

Prognostic Model Construction Using Machine Learning

Ubiquitination-related prognostic models are constructed using various machine learning algorithms. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression is widely employed to prevent overfitting and select the most informative genes [16] [26]. For example, in cervical cancer research, univariate Cox analysis followed by LASSO algorithms identified five key biomarkers (MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, and CXCL8) [16]. Similarly, in lung adenocarcinoma, researchers applied univariate Cox regression, Random Survival Forests, and LASSO Cox regression to identify a four-gene signature (DTL, UBE2S, CISH, and STC1) [26]. Risk scores are calculated using the formula: Risk score = Σ(Coefi × Expi), where Coefi represents the regression coefficient from multivariate Cox analysis, and Expi represents gene expression level [26] [17]. Patients are stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score, with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves used to evaluate prognostic performance.

Immune Infiltration and Tumor Microenvironment Analysis

The tumor immune microenvironment is analyzed using algorithms such as CIBERSORT [32] [33], ESTIMATE [17], and quanTIseq [32]. These tools calculate the abundance of specific immune cell types in tumor tissues based on gene expression data. Studies consistently reveal significant differences in immune cell infiltration between high-risk and low-risk groups defined by ubiquitination-related signatures. For example, in ovarian cancer, the low-risk group showed higher levels of CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages, and follicular helper T cells [17]. In cervical cancer, 12 types of immune cells, including memory B cells and M0 macrophages, exhibited significant differences between risk groups [16]. Additionally, immune checkpoint expression (e.g., PD-1, PD-L1) often correlates with risk scores, suggesting implications for immunotherapy response [16] [26].

Experimental Validation

Bioinformatics findings require experimental validation using various laboratory techniques. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) is routinely employed to verify gene expression trends identified through computational analysis [16] [32] [26]. For example, in cervical cancer research, RT-qPCR confirmed that MMP1, TFRC, and CXCL8 were upregulated in tumor tissues compared to normal controls [16]. Cell culture studies using cancer cell lines (e.g., Caco-2 cells for Crohn's disease research [32], A2780 and HEY cells for ovarian cancer [17]) further validate the functional relevance of identified genes. Gene knockdown or overexpression experiments, followed by assessments of proliferation, migration, and invasion, elucidate the biological roles of specific ubiquitination-related genes. For instance, in ovarian cancer, FBXO45 was experimentally validated to promote cancer growth, spread, and migration via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [17].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Ubiquitination Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Resources | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Caco-2 [32], A2780 [17], HEY [17] | In vitro validation experiments | Well-characterized models for specific cancer types |

| Molecular Biology Kits | RNeasy Mini Kit [31], RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit [32], SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix [32] [31] | RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, qPCR detection | High purity and sensitivity for gene expression analysis |

| Cell Culture Reagents | DMEM/RPMI 1640 media [17], Fetal Bovine Serum [17], Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [32] | Cell maintenance and inflammatory stimulation | Standardized conditions for cell-based assays |

| Bioinformatics Tools | DESeq2 [16], limma [28] [26], clusterProfiler [16], CIBERSORT [32] [33], ESTIMATE [17] | Differential expression, functional enrichment, immune infiltration analysis | Statistical rigor and specialized algorithms for omics data |

| Experimental Assays * | Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining [32], Immunohistochemistry [32] | Histological analysis and protein localization | Morphological assessment and tissue-based validation |

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Implications

The systematic discovery of ubiquitination-related genes has significant clinical implications, particularly in prognostic stratification and therapeutic development. Ubiquitination-related prognostic models demonstrate robust predictive power across multiple cancer types. For instance, in lung adenocarcinoma, the ubiquitination-related risk score (URRS) effectively stratified patients with significantly different survival outcomes (HR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.39-0.73, p < 0.001), with consistent validation in six external cohorts (HR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.36-0.93, p_max = 0.023) [26]. Similarly, in cervical cancer, the risk model based on five ubiquitination-related biomarkers showed predictive value for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival (AUC > 0.6 for all time points) [16]. Beyond prognosis, these models provide insights into therapeutic response. High-risk patients typically exhibit higher tumor mutation burden (TMB), increased tumor neoantigen load (TNB), and elevated PD-1/PD-L1 expression, suggesting enhanced susceptibility to immunotherapy [26]. Additionally, ubiquitination-related genes represent promising therapeutic targets themselves, with several emerging as targets for Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) in ovarian cancer and other malignancies [17].

Comprehensive databases for ubiquitination-related gene discovery have become indispensable resources in cancer research, enabling the development of robust prognostic models and identification of novel therapeutic targets. Specialized databases like iUUCD 2.0 and UUCD provide curated catalogs of ubiquitination enzymes, while broader resources like GeneCards offer comprehensive ubiquitination-related gene sets with relevance scoring. The integration of these databases with standardized analytical workflows—encompassing differential expression analysis, machine learning-based prognostic model construction, immune microenvironment characterization, and experimental validation—has generated significant insights into the role of ubiquitination in cancer biology and clinical outcomes. As mass spectrometry technologies advance [34] and multi-omics datasets expand [35], these databases will continue to evolve, offering increasingly sophisticated resources for unraveling the complexities of ubiquitination in human health and disease. The ongoing refinement of ubiquitination-related biomarkers and therapeutic targets holds particular promise for advancing precision oncology approaches across diverse cancer types.

Pan-Cancer Patterns of Ubiquitination Gene Alterations

Ubiquitination, a critical post-translational modification, has emerged as a central regulatory mechanism in oncogenesis and cancer progression. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) orchestrates the precise degradation of cellular proteins, thereby controlling fundamental processes including cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and immune responses [20]. This enzymatic cascade involves the sequential action of ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes, which collectively target specific substrates for proteasomal degradation [22]. Mounting evidence demonstrates that dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways constitutes a hallmark across diverse cancer types, making systematic analysis of these alterations imperative for both prognostic assessment and therapeutic development [36] [20]. This review synthesizes current understanding of pan-cancer ubiquitination gene alterations, their prognostic significance, and emerging clinical implications.

Key Ubiquitination-Related Genes with Pan-Cancer Significance

Comprehensive bioinformatics analyses across multiple cancer types have identified several ubiquitination-related genes with consistent alterations and prognostic significance.

Table 1: Key Ubiquitination-Related Genes with Pan-Cancer Alterations

| Gene | Encoded Protein | Primary Alteration Types | Cancer Types with Documented Alterations | Prognostic Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2T | E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme | Amplification, mRNA overexpression | Multiple myeloma, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, retinoblastoma, pancreatic cancer [18] [37] | Poor overall survival [18] [37] |

| UBD | Ubiquitin D (FAT10) | Gene amplification, mRNA overexpression, promoter hypomethylation | Gliomas, colorectal carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer [19] | Poor prognosis, higher histological grades [19] |

| UBE2C | E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme | mRNA overexpression | Hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer [22] | Enhanced tumor proliferation, apoptosis inhibition [22] |

| BUB1B, CHEK1, DNMT1, IRAK1, PRKDC | Various ubiquitination-related proteins | Differential expression | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [28] | Significant prognostic value [28] |

| OTUB1 | Deubiquitinating enzyme | Regulatory network alterations | Multiple solid tumors (lung, esophageal, cervical, urothelial, melanoma) [36] | Immunotherapy resistance, poor prognosis [36] |

Table 2: Ubiquitination-Related Risk Models Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Key Genes in Signature | Clinical Applications | Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1 [26] | Prognosis prediction, immune infiltration assessment, therapy response [26] | TCGA training + 6 external GEO datasets validation [26] |

| Ovarian Cancer | 17-gene signature including FBXO45 [17] | Prognostic stratification, immune microenvironment characterization [17] | TCGA/GTEx training + GSE165808/GSE26712 validation [17] |

| Multiple Solid Tumors | URPS (Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signature) [36] | Immunotherapy response prediction, histological subtype classification [36] | 23 datasets across 6 cancer types + single-cell RNA-seq [36] |

| Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma | BUB1B, CHEK1, DNMT1, IRAK1, PRKDC [28] | Prognostic biomarker identification, therapeutic target discovery [28] | TCGA-ESCC, GSE20347, and in-house dataset integration [28] |

Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitination Gene Analysis

Bioinformatics and Multi-Omics Data Integration

Contemporary ubiquitination research employs sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines integrating data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx), and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) databases [18] [36] [26]. Standard analytical workflows include:

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identification of ubiquitination-related differentially expressed genes (URDEGs) using R packages such as "limma" with thresholds typically set at |log fold change| >0.5 and adjusted p-value <0.05 [28].

- Genetic Alteration Analysis: Assessment of mutation frequencies, copy number variations (CNV), and single nucleotide variants (SNV) using cBioPortal and GSCALite databases [18] [19].

- Survival Analysis: Evaluation of prognostic significance through Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox regression models, with patients stratified by median gene expression or risk scores [18] [26].

- Immune Infiltration Correlation: Investigation of relationships between ubiquitination gene expression and tumor immune microenvironment using algorithms such as TIMER and QUANTISEQ [19].

Functional Validation Experiments

Bioinformatics findings require experimental validation through both in vitro and in vivo approaches:

- Gene Expression Validation: Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and western blotting to confirm mRNA and protein expression differences between normal and cancer cells [18] [37]. Standard protocols include RNA extraction with TRIzol, cDNA synthesis with PrimeScript RT Master Mix, and qPCR with SYBR Green chemistry [18].

- Cellular Functional Assays: Investigation of ubiquitination gene effects on proliferation (CCK-8 assays), invasion (Transwell assays), and epithelial-mesenchymal transition [18].

- Pathway Analysis: Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to identify biological processes and signaling pathways affected by ubiquitination genes [18] [28].

Ubiquitination-Associated Signaling Pathways in Cancer

Ubiquitination genes converge on several crucial cancer-related pathways:

- Cell Cycle Regulation: UBE2T and UBE2C participate in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of cell cycle regulators, with UBE2C specifically cooperating with the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) E3 complex to polyubiquitinate proteins for degradation [22].

- p53 Signaling Pathway: Multiple E3 ubiquitin ligases, including MDM2, target p53 for degradation, effectively reducing tumor suppressor activity and promoting oncogenesis [22] [20].

- DNA Repair Mechanisms: UBE2T functions in the Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway, with dysregulation contributing to genomic instability [18] [37].

- Immune Response Regulation: Ubiquitination genes including UBD modulate PD-L1 expression and antigen presentation, thereby influencing antitumor immunity [19].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for Ubiquitination Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Databases | TCGA, GTEx, cBioPortal, GEPIA2.0 [18] [26] [19] | Gene expression analysis, mutation profiling, survival correlation | Multi-omics data integration, user-friendly visualization |

| Experimental Reagents | UBE2T antibody (cat. no. A6853; Abclonal) [18] [37] | Protein detection via western blotting | Specificity for ubiquitination enzymes |

| PrimeScript RT Master Mix, TB Green Premix Ex Taq II [18] [37] | RT-qPCR for gene expression validation | High sensitivity and reproducibility | |

| Cell Line Resources | Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [18] [37] | In vitro modeling of ubiquitination gene functions | Comprehensive collection of characterized cancer cell lines |

| Methodological Approaches | LASSO Cox regression [36] [26] | Prognostic model development | Handles high-dimensional data, prevents overfitting |

| Consensus clustering [26] | Molecular subtype identification | Unsupervised pattern recognition in ubiquitination signatures |

Systematic pan-cancer analyses have revealed consistent patterns of ubiquitination gene alterations across diverse malignancies, with UBE2T, UBD, and UBE2C emerging as particularly significant players. These alterations associate consistently with poor prognosis, advanced disease stages, and therapy resistance, highlighting their potential value as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets. The development of multi-gene ubiquitination signatures shows particular promise for prognostic stratification and treatment response prediction. Future research directions should focus on validating these findings in prospective clinical cohorts and developing targeted therapies that exploit specific vulnerabilities created by ubiquitination pathway alterations. As our understanding of the ubiquitin code in cancer deepens, we anticipate increasing translation of these findings into clinical practice, potentially offering new avenues for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Building Prognostic Signatures: Computational Methods and Clinical Implementation

The advent of large-scale genomic databases has revolutionized cancer research, enabling the identification of molecular patterns across diverse patient populations and tissue types. Among these resources, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project represent three foundational pillars that provide complementary data for comprehensive oncogenomic investigations. TCGA offers a systematically characterized collection of molecular profiles from thousands of tumor samples across numerous cancer types, generating comprehensive genomic data including RNA sequencing, mutations, DNA methylation, and copy number variations [38]. GEO serves as a public functional genomics data repository supporting MIAME-compliant data submissions, containing array- and sequence-based data from diverse experimental conditions [39]. GTEx complements these resources by providing a comprehensive atlas of gene expression and regulation across diverse normal human tissues from nearly 1,000 individuals, establishing the largest resource for studying human gene expression variation across tissues and individuals [38] [40].

In the specific context of evaluating ubiquitination-related genes in cancer, these databases enable researchers to identify dysregulated ubiquitination pathways, develop prognostic models, and discover potential therapeutic targets. Ubiquitination, a critical post-translational modification process that regulates protein degradation and signaling pathways, has been implicated in various cancers [26]. The integration of data from TCGA, GEO, and GTEx allows for systematic investigation of how ubiquitination-related genes contribute to tumorigenesis, disease progression, and treatment response across different cancer types.

Database Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Genomic Databases

| Feature | TCGA | GEO | GTEx |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Molecular characterization of human cancer | Curated gene expression data from diverse studies | Normal human tissue gene expression |

| Data Types | RNA-seq, DNA methylation, copy number variation, mutations, clinical data | Array- and sequence-based data from submitted studies | RNA-seq, whole genome sequencing, histology images, eQTL data |

| Sample Types | Primary tumor, solid tissue normal, blood derived normal, metastatic samples | Varies by submitted study (cell lines, tissues, experimental models) | Normal tissues from 54 tissue sites across nearly 1,000 individuals |

| Cancer Applications | Tumor vs. normal comparison, prognostic modeling, multi-omics integration | Method validation, independent cohort verification, meta-analysis | Normal tissue reference, control for tissue-specific expression |

| Ubiquitination Research Utility | Identify cancer-associated URGs, build prognostic models | Validate findings in independent cohorts | Establish normal URG expression baselines |

Table 2: Data Accessibility and Analytical Considerations

| Consideration | TCGA | GEO | GTEx |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access Method | TCGAbiolinks R package, GDC portal | GEOquery R package, GEO2R web tool | UCSC Xena browser, recount3 R package |

| Normalization | Fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) | Varies by platform and submission | Transcripts per million (TPM) |

| Sample Size | ~11,000 patients across 33 cancer types | Millions of samples across thousands of studies | ~1,000 donors across 54 tissue sites |

| Key Limitations | Limited normal tissue samples, batch effects | Heterogeneous data quality, varied platforms | Post-mortem collection, limited clinical data |

| Integration Potential | High with clinical outcomes | High for validation studies | Essential for normal tissue reference |

Experimental Strategies for Ubiquitination Research

Ubiquitination-Related Gene Selection and Processing

Research into ubiquitination-related genes typically begins with compiling a comprehensive gene set from specialized databases such as the iUUCD 2.0 database, which contains ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1s), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s), and ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) [26]. In colorectal cancer research, one study derived 2,830 ubiquitination-related genes from this resource [41], while ovarian cancer investigations have utilized 929 ubiquitination-related genes categorized into E1 (8 genes), E2 (39 genes), and E3 (882 genes) [25]. For esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), researchers combined ubiquitination-related genes from GeneCards (with relevance scores >5.00), published literature, and the Molecular Signatures Database, resulting in 1,274 unique ubiquitination-related genes [28].

The standard workflow involves identifying differentially expressed genes between tumor and normal tissues using thresholds such as |log fold change| >0.5-1.0 and adjusted p-value <0.05 [28] [25]. The limma R package is commonly employed for differential expression analysis of microarray data, while edgeR or DESeq2 are used for RNA-seq data [28] [25]. The intersection between differentially expressed genes and the ubiquitination-related gene set yields ubiquitination-related differentially expressed genes for further investigation.

Prognostic Model Development

Ubiquitination-related risk models are typically developed using TCGA data as the discovery cohort. For lung adenocarcinoma, one study applied unsupervised clustering, univariate Cox regression, Random Survival Forests, and LASSO Cox regression to identify prognostic ubiquitination-related genes [26]. Similarly, for ovarian cancer, researchers performed univariate Cox analysis followed by LASSO regression and a DEVIANCE test to select 17 genes for their prognostic model [25].

The risk score is calculated using the formula: Risk score = Σ(Coefi × Expri), where Coefi represents the regression coefficient from the multivariate Cox analysis, and Expri represents the gene expression value [26] [25]. Patients are then stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. Model performance is validated using external GEO datasets and evaluated through Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves, and Cox regression analyses adjusting for clinical covariates [26] [41] [25].

Functional Validation and Experimental Follow-up

Experimental validation of bioinformatics predictions strengthens the biological relevance of findings. Standard laboratory reagents and protocols for validating ubiquitination-related gene expression include RNA extraction using reagents such as RNAiso, cDNA synthesis with reverse transcription kits, and quantitative PCR with real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR kits [25]. For functional assays, researchers employ cell culture systems (e.g., DMEM or RPMI 1640 media with fetal bovine serum), transfection reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine 2000), and Western blotting reagents including RIPA lysis buffer, protease inhibitors, and ECL chemiluminescent detection [25].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture | DMEM, RPMI 1640, Fetal Bovine Serum, Trypsin | Maintenance and propagation of cancer cell lines |

| Molecular Biology | RNAiso Reagent, Reverse Transcription Kits, Quantitative PCR Kits | Gene expression analysis and validation |

| Protein Analysis | RIPA Lysis Buffer, Protease Inhibitors, ECL Chemiluminescent Liquid | Protein detection and ubiquitination assessment |

| Functional Assays | Crystal Violet Staining, Paraformaldehyde, Transfection Reagents | Cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion assays |

| Key Antibodies | FBXO45, WNT1, β-catenin, c-myc, GAPDH | Pathway analysis and target validation |

Integrated Data Mining Workflow

Database Integration Workflow for Ubiquitination Research

Analytical Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Differential Expression Analysis

The identification of differentially expressed ubiquitination-related genes employs distinct statistical approaches depending on data types. For microarray data from GEO datasets, the limma R package is commonly used with precision weights (vooma) for linear modeling and empirical Bayes moderation for variance estimation [28] [42]. For RNA-seq data from TCGA and GTEx, researchers typically utilize edgeR or DESeq2 packages that implement negative binomial distributions to model count data [25]. The integration of normal tissue expression data from GTEx with TCGA tumor data enhances the statistical power for identifying cancer-associated ubiquitination-related genes, particularly for cancers with limited normal tissue samples in TCGA [43].

Multiple testing correction is crucial in these analyses, with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure commonly applied to control the false discovery rate. Thresholds for significance typically include adjusted p-values <0.05-0.01 and absolute log2 fold changes >0.5-1.0, depending on the specific study design and sample size [28] [25]. For chromatin accessibility data integration, tools like the "ChIPseeker" package annotate ATAC-seq peaks to genes, which are then intersected with ubiquitination-related differentially expressed genes [43].

Advanced Machine Learning Applications

Machine learning algorithms have become integral to ubiquitination-related cancer research. Random Survival Forests provide robust handling of high-dimensional data and complex interactions, with parameters typically set to ntree=100-500 and variable importance calculated through permutation [26] [43]. LASSO Cox regression performs feature selection and regularization to enhance model interpretability and prevent overfitting, with the optimal penalty parameter (λ) determined through 10-fold cross-validation [26] [41].

For tissue classification and biomarker discovery, Random Forest classifiers with balanced class weights address dataset imbalance, while t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) visualizes high-dimensional integrin expression patterns with perplexity parameters between 30-50 [44]. These approaches have demonstrated high accuracy in distinguishing tissue origins and disease status based on ubiquitination-related gene expression patterns.

Multi-Omics Data Integration

Advanced studies increasingly integrate multiple data types to comprehensively understand ubiquitination in cancer. One lung adenocarcinoma study combined ATAC-seq data measuring chromatin accessibility with RNA-seq data to identify consensus genes affected by both epigenetic and transcriptional regulation [43]. The random forest and LASSO algorithms selected predictive genes, followed by artificial neural network construction with five hidden layers for model development.

Single-cell RNA sequencing data further enhances resolution by identifying cell-type-specific expression of ubiquitination-related genes. Processing pipelines typically include quality control (excluding cells with <200 genes or >15% mitochondrial genes), normalization using the LogNormalize method, identification of highly variable genes, and clustering based on principal components [25]. This approach reveals how ubiquitination-related genes vary across cell populations within tumors.

The strategic integration of TCGA, GEO, and GTEx databases provides a powerful framework for investigating ubiquitination-related genes in cancer research. Each database offers unique strengths—TCGA provides comprehensive molecular profiling of tumors, GEO enables validation across diverse cohorts, and GTEx establishes normal tissue expression baselines. The experimental strategies and analytical workflows outlined herein facilitate the development of robust prognostic models, identification of novel therapeutic targets, and advancement of personalized cancer treatment approaches based on ubiquitination pathways. As these databases continue to expand and novel analytical methods emerge, researchers will uncover increasingly sophisticated insights into the complex roles of ubiquitination in cancer biology.

Bioinformatic Pipelines for Identifying Prognostic UbRG Signatures