Ubiquitin-Like Proteins: From Ancient Origins to Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs), exploring their conserved β-grasp fold structure, intricate enzymatic conjugation cascades, and profound evolutionary lineage tracing back to prokaryotic sulfur-transfer systems.

Ubiquitin-Like Proteins: From Ancient Origins to Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs), exploring their conserved β-grasp fold structure, intricate enzymatic conjugation cascades, and profound evolutionary lineage tracing back to prokaryotic sulfur-transfer systems. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it details the critical functions of UBLs—such as SUMO, NEDD8, and ATG8—in regulating protein degradation, autophagy, DNA repair, and immune response. The content further examines contemporary methodological approaches for studying UBL pathways, analyzes challenges and emerging strategies in therapeutic targeting, including E1, E2, and E3 enzyme inhibitors, and validates these targets through a multiomics and comparative disease biology lens. By integrating foundational knowledge with cutting-edge therapeutic applications, this review serves as a vital resource for navigating the complexity of UBL systems and exploiting their vast potential in biomedical research and clinical intervention.

The Architecture and Evolutionary Legacy of Ubiquitin-Like Proteins

Ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) constitute a family of small proteins involved in the post-translational modification of other proteins, thereby regulating a vast array of cellular functions [1]. The family derives its name from its first discovered and most well-known member, ubiquitin (Ub), which is renowned for its central role in targeting proteins for degradation by the proteasome [1] [2]. Following ubiquitin's discovery, many structurally and evolutionarily related proteins were identified, leading to the recognition of a larger protein family with parallel regulatory processes and similar chemical mechanisms [1] [3]. These UBLs are involved in a widely varying array of cellular functions including autophagy, protein trafficking, inflammation and immune responses, transcription, DNA repair, RNA splicing, and cellular differentiation [1].

Structurally, UBLs are defined by a characteristic three-dimensional structure known as the β-grasp fold [1] [4]. This fold consists of a five-strand antiparallel beta sheet surrounding a central alpha helix [1] [3]. While this structural motif is shared, UBLs are functionally diverse and are primarily classified into two categories based on their ability to form covalent conjugates with other molecules: Type I (conjugated) and Type II (non-conjugated) [1] [3] [5].

Core Structural Characteristics: The β-Grasp Fold

The defining structural feature of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins is the β-grasp fold [1] [4]. This compact protein fold is highly versatile and is found in a wide range of proteins beyond the UBL family, including those with catalytic roles, iron-sulfur cluster scaffolds, and RNA-binding proteins [4].

- Ubiquitin Prototype: Ubiquitin itself is a 76-amino acid polypeptide whose structure reveals a distinctive fold dominated by a beta-sheet with five anti-parallel beta-strands and a single helical segment [4]. The beta-sheet appears to "grasp" the helical segment, giving the fold its name [4].

- Structural Conservation in UBLs: Most UBLs share this core β-grasp architecture, though variations exist [3]. For instance, some UBLs, like ISG15 and FAT10, are composed of tandem β-grasp domains [3]. Members of the ATG8 family possess two additional α-helices near their N-terminus, while ATG12, UFM1, and SUMO proteins often have N-terminal extensions that can be disordered [3].

Despite shared structure, critical surface residues of ubiquitin are not always conserved in other UBLs, leading to distinct interaction surfaces and functions [6]. For example, UBL5/Hub1, an atypical UBL, adopts the β-grasp fold but has a highly charged electrostatic surface with no large hydrophobic patches, unlike ubiquitin, and it lacks the characteristic C-terminal diglycine motif [5] [6].

Classification of UBLs: Type I vs. Type II

The ubiquitin-like protein family is fundamentally divided into two categories based on their mechanism of action and covalent conjugation capabilities.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Type I and Type II Ubiquitin-Like Proteins

| Feature | Type I UBLs (Conjugated) | Type II UBLs (Non-Conjugated) |

|---|---|---|

| Defining Action | Covalently conjugated to target proteins or lipids [1] [3]. | Not covalently conjugated; function as protein-protein interaction domains or integral domains within larger proteins [1] [5]. |

| C-Terminal Motif | Characteristic glycine residue(s) exposed after proteolytic processing [1] [3]. | Lack the C-terminal glycine motif required for conjugation [5] [6]. |

| Expression & Processing | Often expressed as inactive precursors requiring C-terminal proteolysis for activation [1]. | May occur as protein domains genetically fused in a single polypeptide [1]. |

| Representative Members | Ubiquitin, SUMO, NEDD8, ATG8, ATG12, URM1, UFM1, FAT10, ISG15 [1] [3]. | Ubiquilins (e.g., UBQLN1), Hub1/UBL5, Ubiquitin-associated (UBX) domain proteins, Rad23 [7] [5] [8]. |

| Primary Function | Post-translational modification to alter substrate activity, stability, localization, or interactions [1] [2]. | Act as adaptors, scaffolds, or modifiers in processes like proteasomal targeting, splicing, and DNA repair [7] [5] [8]. |

Type I UBLs: Covalent Protein Modifiers

Type I UBLs are characterized by their ability to be activated and covalently ligated to target proteins (or, in one case, a lipid) through an enzymatic cascade [1] [3]. This process is analogous to ubiquitination. A key hallmark of Type I UBLs is a C-terminal sequence that ends with one or two glycine residues [1]. These UBLs are typically expressed as inactive precursors and must be activated by proteases that cleave the C-terminus to expose the reactive glycine [1] [3]. The conjugation cascade involves E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes, which are often specific to each UBL family [1] [3] [2].

Type II UBLs: Non-Covalent Regulators

Type II UBLs contain domains that share the ubiquitin-like β-grasp fold but are not covalently conjugated to other proteins [1] [5]. They generally lack the C-terminal glycine motif [5]. These UBL domains can be found within larger multidomain proteins and often function as protein-protein interaction modules [1] [8]. For example:

- Ubiquilins contain an N-terminal UBL domain and a C-terminal ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain. They function as ubiquitin receptors, shuttling polyubiquitinated proteins to the proteasome by using their UBL domain to bind the proteasome and their UBA domain to bind ubiquitin [7] [8].

- Hub1/UBL5 lacks the diglycine motif and binds its protein partners, such as the spliceosomal protein Snu66, non-covalently to modulate pre-mRNA splicing [5] [6].

- UBX domain proteins contain a domain that structurally mimics ubiquitin but functions as a binding module within larger proteins involved in ubiquitin-related processes [1] [8].

The Conjugation Machinery and Mechanism for Type I UBLs

The conjugation of Type I UBLs to their targets is a tightly regulated, multi-step process that consumes ATP. The well-characterized ubiquitination pathway serves as the paradigm.

The Enzymatic Cascade

The conjugation mechanism involves a cascade of three enzymes:

- Activation (E1): The UBL is first activated by an E1 activating enzyme in an ATP-dependent reaction. The E1 forms a high-energy thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and the C-terminal glycine of the UBL [3] [2].

- Conjugation (E2): The activated UBL is then transferred from the E1 to the active-site cysteine of an E2 conjugating enzyme, forming a similar E2~UBL thioester intermediate [3] [2].

- Ligation (E3): Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the transfer of the UBL from the E2 to a primary amine (typically the ε-amino group of a lysine) on the target protein, resulting in an isopeptide bond [3] [2]. E3s are primarily responsible for substrate recognition and specificity.

Table 2: Human Type I UBLs and Their Cognate Enzymes

| UBL Family | Representative UBLs in Humans | E1 Activating Enzyme | E2 Conjugating Enzyme(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin | Ubiquitin | UBA1, UBA6 | Many [2] |

| SUMO | SUMO1, SUMO2, SUMO3 | UBA2/SAE1 | UBC9 [3] |

| NEDD8 | NEDD8 | UBA3/NAE1 | UBC12, UBE2F [3] |

| ATG8 | LC3A, LC3B, GABARAP | ATG7 | ATG3 [3] |

| ATG12 | ATG12 | ATG7 | ATG10 [3] |

| URM1 | URM1 | UBA4 | – [3] |

| UFM1 | UFM1 | UBA5 | UFC1 [3] |

| FAT10 | FAT10 | UBA6 | UBE2Z [3] |

| ISG15 | ISG15 | UBA7 | UBCH8 [3] |

Deconjugation and Regulation

UBL modifications are dynamic and reversible. A class of enzymes known as deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) or UBL-specific proteases (ULPs) cleave the isopeptide bonds, releasing the UBL from the substrate and allowing for recycling of the UBL tag and termination of the signal [1] [2]. Furthermore, many UBLs, including ubiquitin and SUMO, can themselves be modified by other UBLs, creating a complex network of cross-talk that integrates different cellular signals [1].

Experimental Analysis of UBL Pathways

Research into UBL pathways relies on a suite of molecular and biochemical techniques to dissect the conjugation cascades, identify substrates, and understand functional consequences.

Key Methodologies

- Trapping Reaction Intermediates: A critical strategy for studying the mechanism of E1 and E2 enzymes involves trapping thioester-linked intermediates. This is often achieved by using ATP analogues like ATPγS, which leads to the formation of a stable UBL~adenylate, or by employing E1/E2 active-site mutants (e.g., cysteine to alanine) that prevent thioester transfer, allowing for the isolation and structural characterization of complexes [3].

- In Vitro Reconstitution Assays: Purified components of the UBL pathway (E1, E2, E3, UBL, and substrate) are combined in a test tube to reconstitute the conjugation reaction. This allows for direct manipulation of reaction conditions and identification of minimal essential components [3].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): MS is indispensable for identifying sites of UBL modification on target proteins. Tandem MS (MS/MS) following immunoprecipitation of UBL-conjugated proteins can precisely map the specific lysine residue modified by the UBL [3].

- Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Screening: This technique is used to identify novel protein-protein interactions. For UBLs, it has been successfully used to find interacting partners of Type II UBLs like Hub1/UBL5, revealing connections to spliceosomal components and other factors [5] [6].

- Structural Biology Techniques: X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy have been pivotal in determining the three-dimensional structures of UBLs (e.g., UBL5) and their complexes with binding partners (e.g., the Hub1-Snu66 complex), providing atomic-level insights into recognition and mechanism [6] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for UBL Research

| Research Reagent | Function in UBL Research |

|---|---|

| ATPγS (Adenosine 5'-O-[γ-thio]triphosphate) | A non-hydrolyzable ATP analogue used to trap the UBL~adenylate intermediate on the E1 enzyme for mechanistic studies [3]. |

| Active-Site Mutant E1/E2 Enzymes | E1 or E2 enzymes with catalytic cysteine mutated to alanine (Cys→Ala) are used to block thioester transfer and stabilize complexes for structural analysis [3]. |

| UBL-Specific Proteases (ULPs) | Enzymes like SENP/ULP for SUMO are used to confirm the identity of a UBL modification by cleaving it from substrates in control experiments [1]. |

| Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) Tags | Used to purify UBL-conjugated protein complexes from cell lysates under native conditions for subsequent identification by mass spectrometry [3]. |

| NMR Isotope Labeling (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Production of isotopically labeled UBLs (e.g., UBL5) for NMR studies to determine solution structure and map binding interfaces with partners [6]. |

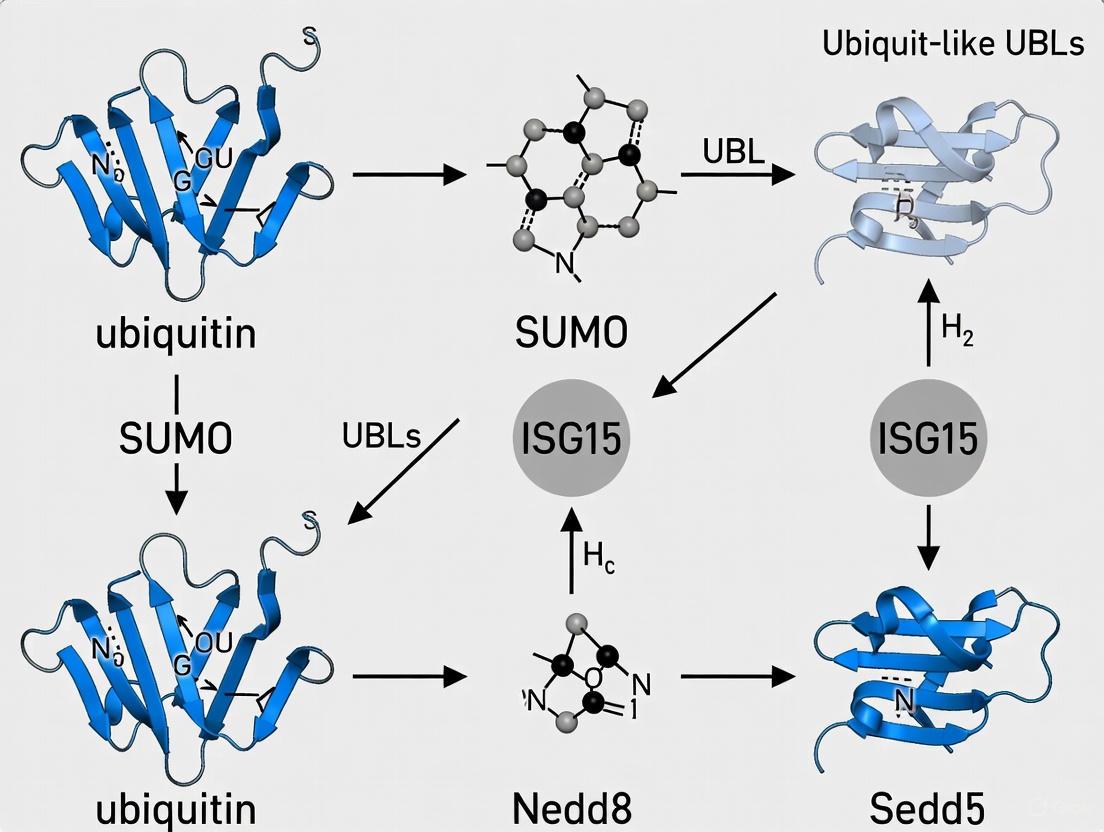

Diagram of UBL Classification and Function

The following diagram summarizes the classification and primary functional roles of the Ubiquitin-Like Protein family.

The ubiquitin-like protein family, defined by the conserved β-grasp fold, is a cornerstone of eukaryotic cellular regulation. The fundamental classification into Type I (conjugated) and Type II (non-conjugated) UBLs reflects a fundamental divergence in their mechanisms of action. Type I UBLs act as reversible covalent modifiers in a manner analogous to ubiquitin, while Type II UBLs function primarily as non-covalent interaction modules within larger proteins. Understanding the distinct characteristics, conjugation machinery, and cellular functions of these two types is essential for comprehending their vast regulatory potential. Continued research into their specific pathways, substrates, and the cross-talk between them remains a vibrant and critical area of cell biology, with direct implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutics.

The β-grasp fold (β-GF) represents a remarkable evolutionary solution in structural biology—a compact and versatile protein architecture that has been recruited for a staggering array of biochemical functions across all domains of life. Prototyped by ubiquitin (Ub), this fold has been extensively studied for its central role in eukaryotic protein regulation through the ubiquitin-conjugation system [9] [1]. However, its functional repertoire extends far beyond this celebrated role, encompassing catalytic functions, iron-sulfur cluster scaffolding, RNA binding, sulfur transfer, co-factor binding, and adaptor functions in signaling complexes [9] [10].

This whitepaper examines the β-grasp fold through the lens of evolutionary structural biology, exploring how a single structural blueprint has been adapted to serve diverse physiological necessities. The persistence of this fold from the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) to modern organisms underscores its fundamental utility in molecular evolution, while its diversification in eukaryotes highlights its critical role in the development of complex cellular regulation [9] [11]. Understanding the structural principles and evolutionary history of the β-grasp fold provides valuable insights for drug development professionals seeking to target ubiquitin-like pathways in disease states, particularly in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and infectious diseases.

Structural Characteristics of the β-Grasp Fold

Core Architectural Features

The β-grasp fold is defined by a highly conserved core structure consisting of a β-sheet with four to five antiparallel strands that partially envelop or "grasp" a single α-helix [9] [1]. This arrangement creates a stable structural scaffold that can withstand significant sequence variation while maintaining structural integrity. The core structural elements typically include:

- A mixed β-sheet with strands arranged in antiparallel fashion

- A single α-helix positioned adjacent to the β-sheet

- Conservative hydrophobic core that stabilizes the fold despite low sequence conservation

- Variable loop regions that confer functional specificity

The fold's stability arises from a conserved hydrophobic core that packs the α-helix against the β-sheet, creating a robust platform that can tolerate extensive surface modifications for specialized functions [9]. This structural robustness has allowed the β-grasp fold to evolve into numerous specialized variants while maintaining its core architectural identity.

Structural Elaborations and Variations

Despite conservation of the core fold, numerous elaborations have evolved to support functional diversity. These include:

- Insertions between core elements: Additional secondary structures such as β-hairpins (e.g., in transcobalamin) or additional helices that extend functional surfaces [12]

- Terminal extensions: N- or C-terminal elongations that add interaction interfaces

- Surface residue specialization: Strategic placement of charged, polar, or hydrophobic residues on the solvent-exposed surface to facilitate specific interactions

- Oligomerization interfaces: Modifications that enable self-association or hetero-complex formation

The prominent β-sheet provides an exposed surface for diverse interactions, and in some cases, these sheets curve to form open barrel-like structures that can accommodate ligands or protein partners [9]. This structural plasticity explains how the fold can support functions as diverse as small molecule binding (e.g., vitamin B12 in transcobalamin) and protein-protein interactions (e.g., in ubiquitin signaling) [12].

Table 1: Major Structural Variations of the β-Grasp Fold

| Structural Variant | Key Features | Representative Proteins | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Ubiquitin-like | Minimal insertions, compact structure | Ubiquitin, NEDD8, SUMO | Protein modification, signaling |

| SLBB Superfamily | β-hairpin insert after helix | Transcobalamin, Nqo1 subunit | Soluble ligand binding |

| Enzyme-associated | Active site integration | NUDIX hydrolases, Staphylokinases | Catalysis, enzymatic activity |

| Fe-S Cluster Binding | Cysteine motifs for cluster coordination | 2Fe-2S Ferredoxins | Electron transport |

| Sulfur Carrier | C-terminal glycines for thiocarboxylate | ThiS, MoaD | Sulfur transfer in cofactor biosynthesis |

Evolutionary Origins and Diversification

Deep Evolutionary Roots

Evolutionary reconstruction indicates that the β-grasp fold had already differentiated into at least seven distinct lineages by the time of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all extant organisms [9] [10]. This early diversification encompassed much of the structural diversity observed in modern versions of the fold, suggesting rapid adaptation to various functional niches in primordial life forms.

The earliest β-grasp members were likely involved in RNA metabolism, with subsequent radiation into various functional niches [9] [10]. The fold's initial recruitment probably exploited its stable platform for RNA interactions, as seen in contemporary TGS domains of aminoacyl tRNA synthetases and other translation regulators [9]. This deep evolutionary history demonstrates the fold's fundamental utility in core cellular processes that date back to the dawn of cellular life.

Prokaryotic Radiation and Functional Innovation

Most of the structural diversification of the β-grasp fold occurred in prokaryotes, where it was adapted for numerous biochemical functions [9] [10]. The fold provided an ideal scaffold for the evolution of various enzymatic activities (e.g., NUDIX phosphohydrolases) and the binding of diverse co-factors (e.g., molybdopterin), each independently evolving on at least three occasions [9]. Similarly, iron-sulfur-cluster-binding emerged at least twice independently within the fold [9].

Comparative genomic analyses reveal that precursors of the eukaryotic ubiquitin system were already present in prokaryotes [13]. These include:

- Metabolic sulfur transfer systems: Combining a Ubl and an E1-like enzyme in pathways for metallopterin, thiamine, cysteine, siderophore, and modified base biosynthesis [13]

- Primitive protein-tagging systems: Including Sampylation in archaea and potential conjugation systems in bacteria with Ubls of the YukD family [13]

- Complete ubiquitin-like pathways: Some prokaryotic systems developed additional elements that closely resemble the eukaryotic state, possessing an E2, a RING-type E3, or both [13]

Eukaryotic Expansion and Specialization

The eukaryotic phase of β-grasp evolution was characterized primarily by a specific expansion of ubiquitin-like (Ubl) members [9] [10]. The eukaryotic UB superfamily diversified into at least 67 distinct families, with approximately 19-20 families already present in the eukaryotic common ancestor [9] [10]. This expansion included:

- Multiple protein-conjugated forms (e.g., ubiquitin, SUMO, NEDD8, ATG12)

- One lipid-conjugated form (ATG8)

- Versions functioning as adaptor domains in multi-module polypeptides

This diversification played a major role in the emergence of characteristic eukaryotic cellular systems, including:

- Nucleo-cytoplasmic compartmentalization

- Vesicular trafficking networks

- Lysosomal targeting pathways

- Protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum

- Chromatin dynamics and regulation

A key aspect of the eukaryotic phase was the dramatic increase in domain architectural complexity, with Ubl domains incorporated into numerous proteins as adaptors or regulatory modules [9]. This expansion facilitated the evolution of complex regulatory networks that underlie eukaryotic cellular complexity.

Figure 1: Evolutionary diversification of the β-grasp fold from LUCA to modern functional systems in prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Functional Diversity and Classification

Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Proteins (UBLs)

Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins represent the most extensively studied class of β-grasp fold proteins. These small proteins are involved in post-translational modification of target proteins through covalent conjugation, typically via their C-terminal glycine residues [1]. The human genome encodes at least eight families of UBLs capable of covalent conjugation: SUMO, NEDD8, ATG8, ATG12, URM1, UFM1, FAT10, and ISG15 [1].

These UBLs regulate an enormous range of physiological processes, primarily by controlling protein interactions with other macromolecules [11]. Their functions include:

- Targeting proteins for degradation (ubiquitin-proteasome system)

- Autophagy (ATG8 and ATG12)

- Transcription regulation (SUMO)

- DNA repair (ubiquitin and SUMO)

- Immune response (ISG15)

- Cell signaling and trafficking (ubiquitin)

The regulatory apparatus for UBL conjugation involves conserved enzyme cascades: E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes, with specific sets of enzymes dedicated to each UBL family [1].

Enzymatic and Catalytic Functions

The β-grasp fold has been independently recruited for enzymatic activities on multiple occasions throughout evolution [9]. These include:

- NUDIX phosphohydrolases: Enzymes that hydrolyze nucleoside diphosphates

- Staphylokinases and streptokinases: Fibrinolytic enzymes in bacteria

- Various other catalytic activities that have evolved at least three times independently

In these proteins, the β-grasp fold provides a stable scaffold that positions catalytic residues and binding pockets for substrates, demonstrating how a structural domain can be adapted for chemical catalysis through strategic placement of active site residues.

Soluble Ligand Binding

A novel superfamily within the β-grasp fold, termed the Soluble-Ligand-Binding β-grasp (SLBB) superfamily, has been identified through sensitive sequence and structure similarity searches [12]. This superfamily includes:

- Transcobalamin and intrinsic factor: Vitamin B12 uptake proteins in animals

- Bacterial polysaccharide export proteins

- Competence DNA receptor ComEA in bacteria

- Cobalamin reductase PduS

- Nqo1 subunit of respiratory electron transport chain

These proteins are characterized by two major clades: the transcobalamin-like clade with a β-hairpin insert after the helix, and the Nqo1-like clade with an insert between strands 4 and 5 of the core fold [12]. Members of both clades interact with ligands in a similar spatial location, with their specific inserts playing important roles in ligand binding.

Iron-Sulfur Cluster Binding

The β-grasp fold serves as a scaffold for iron-sulfur cluster binding in proteins such as 2Fe-2S ferredoxins, which are involved in electron transport [9] [12]. This function has evolved on at least two independent occasions within the fold [9], demonstrating convergent evolution for cofactor binding. The fold provides a stable platform with cysteine residues appropriately positioned for cluster coordination, enabling electron transfer capabilities.

Sulfur Transfer in Cofactor Biosynthesis

The evolutionary link between UBLs and sulfur transfer systems is exemplified by proteins like ThiS and MoaD, which function as sulfur carriers in thiamine and molybdopterin biosynthesis, respectively [9] [11]. These proteins share not only the β-grasp fold with ubiquitin but also similar activation mechanisms involving C-terminal thiocarboxylate formation catalyzed by E1-like enzymes (ThiF and MoeB) [9]. The eukaryotic protein URM1 represents a molecular fossil that functions both as a UBL and a sulfur carrier, bridging these functional classes [1].

Adaptor Functions in Protein Complexes

The β-grasp fold frequently serves as an adaptor domain in larger multidomain proteins, mediating specific protein-protein interactions in various contexts [9]. Examples include:

- RA, PB1, and DCX domains: Adaptors in animal signaling proteins

- FERM N-terminal domains: Mediators of membrane-cytoskeleton interactions

- UBX domains: Ubiquitin-regulatory domains in larger polypeptides

These adaptor functions leverage the fold's stable platform and customizable interaction surfaces to facilitate the assembly of macromolecular complexes.

Table 2: Functional Classification of β-Grasp Fold Proteins

| Functional Category | Key Examples | Organismic Distribution | Central Biochemical Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Modification | Ubiquitin, SUMO, NEDD8 | Eukaryotes | Post-translational modification, signaling |

| Sulfur Transfer | ThiS, MoaD, URM1 | All domains | Cofactor biosynthesis |

| Electron Transfer | 2Fe-2S Ferredoxins | Bacteria, Eukaryotes | Electron transport |

| Soluble Ligand Binding | Transcobalamin, ComEA | Bacteria, Animals | Vitamin uptake, metabolite binding |

| RNA Binding | TGS domain, IF3 | All domains | Translation regulation |

| Enzymatic Catalysis | NUDIX hydrolases, Staphylokinases | Primarily bacteria | Hydrolysis, fibrinolysis |

| Adaptor Functions | RA, PB1, FERM domains | Primarily eukaryotes | Protein complex assembly |

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Identification and Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive identification of β-grasp fold members requires specialized bioinformatic approaches due to the fold's small size and high sequence divergence. Successful strategies include:

- Multi-pronged sequence-structure searches: Iterative sequence profile searches using PSI-BLAST combined with structural comparisons [9]

- Hidden Markov Model (HMM) searches: Profile-based detection of distant homologs [12]

- Structural similarity searches: Using programs like DALI to identify fold similarities despite sequence divergence [12]

- Topological analysis: Recognition of characteristic β-grasp structural motifs

These approaches have revealed previously unrecognized members of the fold, including domains in bacterial flagellar and fimbrial assembly components, and five new UB-like domains in eukaryotes [9].

Structural Determination and Analysis

Structural characterization of β-grasp proteins employs multiple complementary techniques:

- X-ray crystallography: Provides high-resolution structures of fold variants

- NMR spectroscopy: Reveals dynamic properties and solution structures

- Computational modeling: Rosetta-based protein design to explore fold compatibility [14]

- Chemical shift analysis: CS-Rosetta for structure determination from NMR data [14]

These methods have been instrumental in identifying core distinguishing features of the fold and numerous elaborations, including several previously unrecognized variants [9].

Functional Assay Systems

Functional characterization of β-grasp proteins employs specialized assay systems tailored to their diverse activities:

- Binding assays: For protein-protein, protein-ligand, and protein-RNA interactions

- Enzymatic activity assays: For catalytic members like NUDIX hydrolases

- Conjugation assays: For UBLs, measuring transfer to target proteins

- Inhibition studies: For functional characterization of engineered variants [14]

For example, inhibition constants (Kᵢ) for engineered protease inhibitors based on the S6 ribosomal protein fold can be measured using engineered subtilisin proteases and fluorescent substrates [14].

Figure 2: Integrated research methodology for studying β-grasp fold proteins, combining bioinformatic, structural, and functional approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for β-Grasp Fold Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Activating Enzyme (E1) | Activates UBLs through ATP-dependent adenylation | UBL conjugation assays, mechanistic studies |

| Ubiquitin Conjugating Enzymes (E2) | Transfers activated UBL to E3 or substrate | Enzyme cascade reconstitution, specificity studies |

| Ubiquitin Ligases (E3) | Mediates target specificity in UBL transfer | Substrate identification, functional characterization |

| Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs) | Cleaves UBL conjugates | Conjugation dynamics, signaling regulation studies |

| Proteasome Complexes | Recognizes and degrades ubiquitinated substrates | Functional validation of ubiquitination |

| NMR Isotope-labeled Media | Production of ¹⁵N/¹³C-labeled proteins for NMR | Structural studies, dynamics characterization |

| Subtilisin Protease Columns | Affinity purification of engineered inhibitors | Functional analysis of engineered β-grasp variants [14] |

| Cross-linking Reagents | Stabilizes transient protein complexes | Interaction mapping, structural characterization |

| Fluorescent Ubiquitin Probes | Monitoring ubiquitination in cellular contexts | Live-cell imaging, kinetic studies |

| Computational Design Software | Rosetta-based protein design | Engineering fold-switching variants [14] |

Engineering and Therapeutic Applications

Protein Engineering and Design

Recent advances have demonstrated the potential for engineering β-grasp proteins with novel properties and functions. Notably, researchers have successfully designed mutational pathways connecting three common folds (3α, β-grasp, and α/β-plait) [14]. This engineering approach involves:

- Threading sequences of smaller folds through larger fold structures

- Identifying alignments that minimize catastrophic interactions

- Computational design using tools like Rosetta to resolve unfavorable interactions

- Experimental validation of designed proteins using NMR and functional assays

These efforts have created protein pairs where a single sequence can adopt either a 3α or β-grasp fold in smaller forms but an α/β-plait fold in larger forms [14]. The ability to design such fold-switching proteins highlights the underlying ambiguity in the protein folding code and demonstrates how new protein structures can evolve via abrupt fold switching.

Therapeutic Targeting Opportunities

The ubiquity and functional importance of β-grasp proteins, particularly in ubiquitin signaling pathways, make them attractive therapeutic targets. Key targeting strategies include:

- Proteasome inhibitors (e.g., bortezomib) for cancer treatment

- DUB inhibitors for modulating ubiquitin signaling

- E1-E2-E3 cascade inhibitors for specific pathway modulation

- SUMOylation modifiers for cancer and neurological disorders

- ISG15 pathway modulators for antiviral applications

Understanding the structural principles and evolutionary relationships of β-grasp proteins provides valuable insights for drug development, particularly in designing specific inhibitors that exploit conserved structural features while targeting functionally divergent family members.

The β-grasp fold represents a remarkable example of evolutionary economy—a single structural blueprint adapted through billions of years of evolution to serve diverse functional roles. From its origins in primordial RNA metabolism to its expansion in eukaryotic regulatory systems, this versatile fold has been continuously reinvented while maintaining its core architectural identity.

The fold's functional versatility stems from its stable structural core, which can tolerate extensive surface modifications and insertions that create specialized functional sites. This plasticity has allowed the evolution of functions ranging from enzymatic catalysis to signal transduction, with different functional classes emerging independently on multiple occasions throughout evolutionary history.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the structural principles and evolutionary relationships of β-grasp proteins provides valuable insights for manipulating these systems therapeutically. The continued discovery of new β-grasp variants and functions underscores the importance of this fold in cellular physiology and highlights potential opportunities for therapeutic intervention in human diseases.

The conjugation of ubiquitin (Ub) and ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubls) represents a crucial post-translational modification mechanism that regulates a vast array of cellular processes in eukaryotic cells. This modification involves the covalent attachment of these small protein modifiers to target substrates, thereby influencing their activity, stability, subcellular localization, and macromolecular interactions [15] [3]. The fundamental importance of these pathways is evidenced by their involvement in essential physiological processes including cell division, immune responses, embryonic development, and protein quality control [16]. Defects in these conjugation systems are associated with numerous diseases, particularly cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions [17] [18].

The conjugation of Ub and Ubls is achieved through a conserved enzymatic cascade comprising activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligase (E3) enzymes [15] [3]. These multienzyme cascades utilize labile thioester intermediates, extensive conformational changes, and vast combinatorial diversity of short-lived protein-protein complexes to conjugate Ub/Ubls to various substrates in a tightly regulated manner [19]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of the E1-E2-E3 conjugation cascade, examining the structural mechanisms, evolutionary origins, and experimental approaches that define this essential biological system.

The Enzymatic Cascade: E1, E2, and E3 Mechanisms

E1 Activating Enzymes: The Apex of the Cascade

E1 enzymes serve at the apex of each Ubl conjugation cascade, initiating the activation process and directing the Ubl to downstream pathways [16]. These enzymes employ a conserved mechanism to activate the C-terminus of Ub/Ubls in an ATP-dependent process. The human genome encodes eight E1 enzymes that initiate conjugation for Ub and various Ubls, each exhibiting specificity for their cognate modifiers [16].

The activation mechanism proceeds through two distinct steps [16] [18]. First, the E1 enzyme binds MgATP and ubiquitin, catalyzing ubiquitin C-terminal acyl-adenylation. In the second step, the catalytic cysteine residue in the E1 active site attacks the ubiquitin~adenylate to form an activated ubiquitin~E1 thioester complex (the tilde "~" represents a high-energy thioester bond). Throughout this mechanism, the E1 enzyme binds two ubiquitin molecules simultaneously, with the secondary ubiquitin facilitating conformational changes during the subsequent transthioesterification process [18].

Table 1: Human E1 Enzymes and Their Cognate Ubls

| E1 Enzyme | Composition | Cognate Ubl(s) | Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBA1 | Homodimeric | Ubiquitin | Protein degradation, signaling |

| UBA6 | Homodimeric | Ubiquitin, FAT10 | Immune regulation |

| UBA2/SAE1 heterodimer | Heterodimeric | SUMO1, SUMO2, SUMO3 | Nuclear transport, transcription |

| UBA3/NAE1 heterodimer | Heterodimeric | NEDD8 | Cullin-RING ligase activation |

| ATG7 | Homodimeric | ATG8, ATG12 | Autophagy |

| UBA4 | Homodimeric | URM1 | Sulfur transfer, oxidative stress |

| UBA5 | Homodimeric | UFM1 | Endoplasmic reticulum stress |

| UBA7 | Homodimeric | ISG15 | Immune response, antiviral defense |

E2 Conjugating Enzymes: Central Hubs in Specificity

E2 enzymes (ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes or UBCs) function as central hubs in the conjugation cascade, receiving the activated Ubl from E1 and cooperating with E3 ligases to modify specific substrates [20]. The human genome encodes at least 38 E2s, which can be classified into 17 phylogenetically distinct subfamilies [20]. These enzymes contain a conserved core ubiquitin-conjugating (UBC) domain that houses the active-site cysteine residue responsible for thioester linkage with the Ubl.

E2 enzymes have emerged as key mediators of ubiquitin chain assembly, governing the switch from chain initiation to elongation, regulating the processivity of chain formation, and establishing the topology of assembled chains [20]. After being charged with ubiquitin, E2s engage specific E3s to catalyze substrate ubiquitylation. A single E2 can interact with multiple different E3s, with members of the UBE2D family exhibiting particularly broad E3 specificity [20].

Table 2: Selected Human E2 Enzymes and Their Characteristics

| E2 Enzyme | Alternative Names | Cognate Ubl | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2D1 | UbcH5a | Ubiquitin | Works with multiple RING E3s |

| UBE2N | Ubc13 | Ubiquitin | Forms K63-linked chains with UBE2V1 |

| UBE2C | UbcH10 | Ubiquitin | Cell cycle regulation |

| UBE2L3 | UbcH7 | Ubiquitin | Works with HECT E3s |

| UBC9 | - | SUMO | Sole SUMO E2 |

| UBE2M | Ubc12 | NEDD8 | Neddylation of cullins |

| UBE2Z | - | FAT10 | Immune regulation |

| UBCH8 | - | ISG15, Ubiquitin | Antiviral response |

E3 Ligases: Determinants of Substrate Specificity

E3 ubiquitin ligases function as the final enzymatic components in the conjugation cascade, providing substrate specificity through direct recognition of target proteins [15]. The human genome encodes an estimated 600-1,000 E3s, which can be broadly categorized into three major classes based on their structural features and mechanisms of action: Really Interesting New Gene (RING), U-box, and Homologous to E6AP C-Terminus (HECT) domain-containing ligases [20].

RING and U-box E3s function primarily as scaffolds that simultaneously bind charged E2s and substrate proteins, facilitating direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate without forming a covalent E3-ubiquitin intermediate [21]. In contrast, HECT E3s employ a two-step mechanism where ubiquitin is first transferred from the E2 to an active-site cysteine within the HECT domain, forming a thioester intermediate, before final conjugation to the substrate [21]. This mechanistic diversity allows for precise temporal and spatial control over protein ubiquitylation, enabling specific regulation of countless cellular processes.

Evolutionary Origins and Conservation

The Ub/Ubl conjugation systems have their origins in prokaryotic biosynthetic pathways, with structural and mechanistic parallels observed in bacterial sulfur transfer systems [16] [22]. The bacterial proteins MoaD and ThiS, which share the characteristic Ubl fold, function in sulfur incorporation for the biosynthesis of molybdopterin and thiamine, respectively [16]. These proteins are activated by C-terminal acyl-adenylation through the bacterial enzymes MoeB and ThiF, which share significant sequence homology and structural similarity with the adenylation domain of eukaryotic E1s [16] [2].

The evolutionary relationship between these prokaryotic biosynthetic systems and eukaryotic Ubl conjugation pathways highlights the exaptation of ancient enzymatic mechanisms for novel regulatory functions in eukaryotic cells [22] [2]. The core β-grasp fold characteristic of Ub and Ubls appears in these prokaryotic antecedents, with the eukaryotic system expanding through gene duplication and functional diversification [3]. Surprisingly, proteins similar to Ubl-conjugating and Ubl-deconjugating enzymes appear to have already become widespread by the time of the last universal common ancestor, suggesting that Ubl-protein conjugation is not exclusively a eukaryotic invention [2].

The conservation of key mechanistic features across evolution is remarkable. The core adenylation chemistry, thioester transfer, and ultimate isopeptide bond formation remain fundamentally similar from prokaryotic sulfur transfer to eukaryotic protein modification [16]. This conservation underscores the functional efficiency of this enzymatic strategy and explains its adaptation for diverse regulatory purposes throughout eukaryotic evolution.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Chemical Tools for Probing Conjugation Mechanisms

Recent advances in chemical biology have yielded sophisticated tools for studying the transient intermediates and complex dynamics of the Ub/Ubl conjugation cascades [19]. These approaches are essential because the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascades utilize labile thioester intermediates and short-lived protein-protein complexes that are often too elusive for direct observation under physiological conditions [19].

One powerful strategy involves the development of mechanism-based probes that trap specific intermediates in the activation and transfer process. These include ATP analogs, ubiquitin variants with modified C-termini, and oxime/hydrazide-based probes that form stable adducts with thioester intermediates [19]. Additionally, disulfide-trapping approaches using engineered E1 and E2 variants containing additional cysteine residues can stabilize otherwise transient E1-E2 complexes for structural characterization [19].

Phage display has emerged as a particularly valuable methodology for profiling the specificity of E1 enzymes toward the C-terminal sequences of Ub/Ubls [21]. This approach involves creating libraries of Ub variants with randomized C-terminal sequences displayed on phage surfaces, followed by selection based on the catalytic formation of thioester conjugates with E1 enzymes [21]. This method has revealed that while certain residues (particularly Arg72) are absolutely required for E1 recognition, other positions in the Ub C-terminus can accommodate substantial variation while maintaining E1 reactivity [21].

Structural Biology Techniques

Structural biology has been instrumental in elucidating the molecular mechanisms of the conjugation cascade. X-ray crystallography has provided high-resolution snapshots of various states in the E1 catalytic cycle, including the E1-UB/ATP complex, the ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate, and the E1-E2 transthioesterification complex [16]. These structures have revealed the dramatic conformational changes that occur during ubiquitin activation and transfer.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has enabled visualization of larger complexes, including full-length E3 ligases bound to their cognate E2s and substrates. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has provided insights into the dynamics of these processes, particularly for transient complexes that are difficult to crystallize. Together, these techniques have revealed how E1s serve as molecular switches that undergo substantial conformational rearrangements to coordinate the different steps of Ubl activation and transfer to E2s [16].

Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying the Conjugation Cascade

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Phage-displayed UB library [21] | Profiling E1 specificity toward UB C-terminal sequences | Randomized residues 71-75 of UB; library size ~10^8 clones |

| Biotin-CoA conjugate [21] | Labeling PCP-E1 fusions via Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase | Enables immobilization of E1 enzymes for phage selection |

| ATP analogs (e.g., ATPγS) [19] | Trapping adenylate intermediates | Non-hydrolyzable or slowly hydrolyzable ATP variants |

| Ubiquitin C-terminal mutants [21] | Studying sequence requirements for E1 recognition and DUB resistance | Includes L73F, L73Y, G75S, G75D, G75N mutants |

| Disulfide-trapping E1/E2 variants [19] | Stabilizing transient E1-E2 complexes for structural studies | Engineered cysteine residues for covalent crosslinking |

| Activity-based E1 probes [19] | Monitoring E1 activation states and inhibitor screening | Covalently modify active site cysteine |

Therapeutic Targeting and Diagnostic Applications

The Ub/Ubl conjugation pathways represent promising therapeutic targets for numerous diseases, particularly cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and viral infections [17]. The clinical success of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib for multiple myeloma validation this approach and has stimulated intensive drug discovery efforts targeting various components of the conjugation machinery [17].

E1 enzymes have emerged as particularly attractive targets due to their position at the apex of the cascades. The NEDD8 E1 inhibitor MLN4924 (pevonedistat) has shown promising clinical activity by blocking cullin neddylation and thereby modulating the activity of cullin-RING E3 ligases [17]. Similarly, inhibitors targeting the SUMO E1 and ubiquitin E1 enzymes are under investigation for cancer therapy [17].

E2 enzymes offer another attractive point for therapeutic intervention, with their central role in determining ubiquitin chain topology and their more limited diversity compared to E3s [20]. E3 ligases present the greatest challenge for drug discovery due to their extensive diversity, but also offer the potential for exquisite specificity [17]. Small molecules targeting specific protein-protein interactions between E3s and their substrates are currently in development, with MDM2 inhibitors representing a prominent example [17].

Visualizing the Conjugation Cascade

The following diagram illustrates the core E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade and the key conformational changes that drive ubiquitin activation and transfer.

Diagram 1: The E1-E2-E3 Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade. This diagram illustrates the sequential steps of ubiquitin activation and transfer, highlighting the key intermediates and conformational changes involved.

The subsequent diagram details an experimental workflow for phage display selection of ubiquitin variants based on their reactivity with E1 enzymes, a key methodology for profiling E1 specificity.

Diagram 2: Phage Display Workflow for Profiling E1 Specificity. This experimental methodology enables identification of ubiquitin C-terminal sequences that are reactive with E1 enzymes through iterative selection rounds.

The E1-E2-E3 conjugation cascade represents a sophisticated enzymatic system that has evolved from prokaryotic antecedents to become a central regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cell biology. The structural and mechanistic insights gained from biochemical, structural, and chemical biology approaches have revolutionized our understanding of these pathways and created new opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Continued investigation of these systems will undoubtedly yield further insights into their biological functions and enhance our ability to target them for treating human disease.

Ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) are a family of protein modifiers that share a characteristic three-dimensional structure known as the β-grasp fold and are conjugated to target substrates via a conserved enzymatic cascade [23] [24]. This family includes prominent members such as SUMO, NEDD8, ISG15, ATG8, and ATG12, which regulate a diverse array of cellular processes including transcription, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, autophagy, and immune responses [23] [24] [25]. The attachment of UBLs to cellular proteins represents a crucial post-translational modification mechanism that expands the functional diversity of the proteome, allowing cells to rapidly fine-tune protein activity, stability, localization, and interaction networks in response to genetic and environmental changes [2] [25].

The mechanistic conservation across UBL pathways is remarkable. Typically, UBL conjugation involves a three-step enzymatic cascade: an E1 activating enzyme catalyzes UBL activation in an ATP-dependent manner, an E2 conjugating enzyme accepts the activated UBL, and an E3 ligase facilitates the transfer of the UBL to specific target proteins [24] [26]. This modification is dynamic and reversible, with dedicated proteases responsible for UBL deconjugation and recycling [27]. While these pathways share mechanistic similarities, each UBL system maintains specificity through dedicated enzymatic machinery [24].

Table: Core Components of Major UBL Pathways

| UBL | E1 Activating Enzyme | E2 Conjugating Enzyme | E3 Ligase Examples | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUMO | SAE1/SAE2 heterodimer | Ubc9 | PIAS family, RanBP2 | Nuclear transport, transcription, DNA repair |

| NEDD8 | UBA3-NAE1 heterodimer | Ubc12 | RBX1/2 | Cullin activation, ubiquitin ligase regulation |

| ISG15 | UBE1L | UbcH8 | HERC5, TRIM25 | Antiviral response, immune modulation |

| ATG12 | ATG7 | ATG10 | ATG5-ATG16 complex (E3-like) | Autophagosome formation |

| ATG8 | ATG7 | ATG3 | ATG12-ATG5-ATG16 complex | Autophagosome membrane expansion |

The UBL Conjugation Machinery

Structural and Mechanistic Conservation

The conjugation of UBLs to target proteins follows a conserved enzymatic pathway that begins with UBL activation. Structural studies reveal that E1 activating enzymes share a conserved domain architecture consisting of two pseudosymmetric adenylation domains that form a composite active site for ATP•Mg²⁺ and UBL binding, a catalytic cysteine domain that harbors the active-site cysteine needed for E1~UBL thioester bond formation, and the Ub-fold domain (UFD) that interacts with E2 proteins [24]. The E1 enzyme catalyzes adenylation of the UBL C-terminal glycine, followed by nucleophilic attack by its conserved active-site cysteine, forming an E1~UBL thioester intermediate [24]. A second UBL adenylation completes formation of the E1 ternary complex, which then catalyzes thioester transfer of the UBL to the conserved active-site cysteine of the E2 conjugating enzyme [24].

Significant conformational changes enable this process. During E1 activation, the CYS domain rotates approximately 130°, transiting the catalytic cysteine to a position proximal to the UBL C-terminal adenylate [24]. Similarly, a ~25° rotation of the UFD brings the E2 from a distal position to a proximal position suitable for thioester transfer [24]. These coordinated movements and disassembly of the adenylation active site help drive the reaction forward.

UBL-Specific Enzymatic Cascades

Each UBL employs a dedicated set of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes that confer pathway specificity:

SUMOylation: The heterodimeric E1 enzyme (SAE1/SAE2) activates SUMO, which is transferred to the sole E2 enzyme Ubc9 [28]. Ubc9 can directly recognize substrates through non-covalent interactions with SUMO molecules and may bypass E3 ligases under specific conditions, though E3s like the PIAS family and RanBP2 enhance specificity and efficiency [28].

NEDD8ylation: The NEDD8 E1 (UBA3-NAE1 heterodimer) activates NEDD8, which is transferred primarily to the E2 Ubc12 [24] [25]. The best-characterized NEDD8 targets are cullin proteins, which require neddylation for activation of their E3 ubiquitin ligase activity [25].

ISG15ylation: UBE1L serves as the E1 for ISG15, with UbcH8 as its primary E2 [2] [28]. ISG15 E3 ligases include HERC5 and TRIM25, which facilitate ISG15 conjugation to target proteins involved in antiviral defense [28].

ATG8 and ATG12 Conjugation: Both UBLs share the same E1 enzyme (ATG7) but have distinct E2s—ATG10 for ATG12 and ATG3 for ATG8 [23] [25]. The ATG12-ATG5 conjugate then functions as an E3-like complex to promote ATG8 lipidation [25].

Major UBL Families: Structures and Functions

SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier)

SUMO proteins possess a molecular weight of approximately 11 kDa and contain a characteristic βββαβαβ fold with a C-terminal diglycine motif [28]. Mammals encode five SUMO paralogs (SUMO1-5) that exhibit both complementary and antagonistic roles in cellular regulation [28]. For instance, SUMO-1 enhances transcriptional activity by promoting the interaction between specificity protein-1 (Sp1) and histone acetyltransferase p300, while SUMO-2 disrupts this complex and destabilizes Sp1 [28].

SUMOylation influences numerous cellular processes through several mechanisms. It modulates protein-protein interactions via recognition by SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs), alters subcellular localization, affects protein stability, and regulates transcriptional activity [28]. Unlike ubiquitination, SUMOylation does not typically target proteins for degradation but rather acts as a molecular switch that controls protein function, complex formation, and trafficking between nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments [28].

NEDD8 (Neural Precursor Cell Expressed, Developmentally Down-regulated 8)

NEDD8 shares approximately 55% sequence identity with ubiquitin and possesses a nearly identical three-dimensional structure, with the exception of two surface regions that mediate specialized interactions with target proteins [29]. The primary function of NEDD8 is the regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases (CRLs), which constitute the largest family of E3 ubiquitin ligases [25] [29].

Neddylation of cullin proteins induces a conformational change that activates CRLs by promoting their assembly and facilitating ubiquitin transfer to substrates [29]. Through this mechanism, NEDD8 indirectly regulates the ubiquitination and degradation of numerous proteins involved in cell cycle progression, signaling transduction, and transcription [25] [29]. The NEDD8 pathway is therefore intimately connected to the ubiquitin-proteasome system, serving as a critical regulator of its activity.

ISG15 (Interferon-Stimulated Gene 15)

ISG15 is a unique UBL consisting of two ubiquitin-like domains in tandem, with 32% and 37% identity to ubiquitin at its N- and C-termini, respectively [28] [25]. It is strongly induced by type I interferons and functions as a key mediator of antiviral immunity [2] [28]. ISG15 can exist as both a free molecule and a conjugated form, each with distinct biological activities.

As a covalent modifier, ISG15 conjugates to numerous target proteins in infected cells, modulating their function to establish an antiviral state [28]. Free ISG15 can act as a cytokine with immunomodulatory properties [28]. The conjugation of ISG15 to viral and host proteins can interfere with viral replication through various mechanisms, including blocking viral assembly, counteracting host restriction factors, and modulating immune signaling pathways [28].

ATG8 and ATG12 (Autophagy-related Proteins 8 and 12)

ATG8 and ATG12 are central regulators of autophagy, an intracellular degradation system that delivers cytoplasmic components to lysosomes for breakdown and recycling [23] [25]. ATG12 is conjugated to ATG5 in a ubiquitin-like reaction that requires the E1 enzyme ATG7 and the E2 enzyme ATG10 [25]. The ATG12-ATG5 conjugate then forms a complex with ATG16L1, which functions as an E3-like enzyme to promote the lipidation of ATG8 [25].

ATG8 is activated by ATG7 (E1) and transferred to ATG3 (E2) before being conjugated to the lipid phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) [25]. This lipidated form of ATG8 localizes to autophagosomal membranes, where it facilitates membrane expansion and curvature and serves as a docking site for receptors that recruit cargo destined for degradation [25]. The ATG8/ATG12 conjugation systems are essential for autophagosome biogenesis and selective autophagy, playing critical roles in cellular homeostasis, adaptation to stress, and elimination of intracellular pathogens [23].

Table: Functional Roles and Disease Associations of Major UBLs

| UBL | Key Biological Functions | Cellular Localization | Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUMO | Transcriptional regulation, genome stability, stress response, protein localization | Predominantly nuclear | Cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, heart diseases |

| NEDD8 | Activation of cullin-RING ligases, cell cycle regulation, transcription | Nuclear and cytoplasmic | Cancer (often overexpressed), targeted by therapeutic inhibitor MLN4924 |

| ISG15 | Antiviral defense, immune modulation, interferon signaling | Cytoplasmic, secreted form | Infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders |

| ATG12 | Autophagosome formation, mitochondrial homeostasis | Cytoplasmic, autophagosomal membranes | Neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, inflammatory disorders |

| ATG8/LC3 | Autophagosome membrane expansion, cargo recognition | Autophagosomal membranes, lipidated form | Neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, metabolic disorders |

Experimental Methods for UBL Research

The bioUbL Platform for Studying UBL Modifications

The bioUbL system represents a comprehensive set of tools for studying UBL modifications, based on multicistronic expression and in vivo biotinylation using the E. coli biotin protein ligase BirA [30]. This approach addresses several challenges in UBL research, including the cost and specificity of reagents, removal of UBLs by proteases, distinguishing UBL conjugates from interactors, and the low abundance of modified substrates [30].

The bioUbL methodology involves:

- Multicistronic vector design encoding three open reading frames separated by viral 2A sequences

- In vivo biotinylation of UBLs containing an N-terminal biotinylation-target peptide (Bio tag)

- Purification under denaturing conditions to inactivate deconjugating enzymes and preserve UBL modifications

- Stringent washes using the high-affinity biotin-streptavidin interaction to remove UBL interactors and non-specific background [30]

This system has been successfully applied in Drosophila cells, transgenic flies, and mammalian cells, identifying extensive sets of putative SUMOylated proteins and novel potential substrates for UFM1 [30]. The flexibility of this platform makes it a powerful complement to existing strategies for studying UBL modifications.

Proteomic Approaches for UBL Substrate Identification

Advanced proteomic techniques have been developed to detect and quantify UBL modifications:

- Enrichment strategies using epitope-tagged UBLs (e.g., 6xHIS, FLAG, HA) or specific antibodies enable isolation of UBL-conjugated proteins [30].

- Mass spectrometry analysis of tryptic peptides containing the characteristic Gly-Gly remnant left after digestion of UBL-modified substrates helps identify modification sites [23].

- The PRISM method (for SUMO) involves chemical blockade of all free lysines, treatment with SUMO-specific proteases, biotin-tagging of freed lysines, and identification by high-resolution mass spectrometry [30].

- Activity-based probes and inhibitors targeting UBL-specific enzymatic machinery facilitate capture, identification, and characterization of UBL pathway components [23].

Diagram: The Ubiquitin-Like Protein Conjugation Cascade. UBLs are first processed to expose their C-terminal glycine, then undergo E1-mediated activation, E2-mediated conjugation, and E3-mediated ligation to specific substrates, ultimately triggering diverse cellular responses.

Research Reagent Solutions for UBL Studies

Table: Essential Research Tools for UBL Pathway Investigation

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity-based Probes | Suicide substrates, Ub/Ubl-adenylate analogs | Enzyme mechanism studies, inhibitor screening | Covalently trap intermediate states, enable structural studies |

| Biotinylation Tools | bioUbL system, BirA ligase, AviTag | Purification under denaturing conditions, MS analysis | High-affinity streptavidin binding, minimal background |

| Specific Inhibitors | MLN4924 (NEDD8 E1), PYR-41 (Ub E1) | Pathway validation, therapeutic development | Mechanism-based inhibition, target specificity |

| Protease-resistant Mutants | SUMO2-T90R (MS optimization) | Proteomic identification of modification sites | Enhanced peptide detection, reduced ambiguity |

| Chain Formation Mutants | SUMO2-K11R (chain formation study) | Elucidating functions of poly-Ubl chains | Disrupted specific lysine for chain formation |

| Tagged UBL Variants | 6xHIS-FLAG, 6xHIS-HA, FLAG-TEV | Affinity purification, interactome studies | Compatibility with multiple detection methods |

Therapeutic Targeting of UBL Pathways

Dysregulation of UBL pathways is implicated in various human diseases, making them attractive therapeutic targets. In cancer, abnormal UBL activity contributes to uncontrolled proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and metastasis [25] [29]. Notable examples include:

NEDD8 pathway inhibition: MLN4924 (Pevonedistat) inhibits the NEDD8 E1 activating enzyme, preventing cullin neddylation and subsequent ubiquitin ligase activation [29]. This agent has demonstrated anticancer activity in clinical trials by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [29].

SUMOylation in cancer: SUMO pathway components are frequently overexpressed in malignancies, and SUMO inhibition sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapy and radiation [25].

NUB1 as a tumor suppressor: The protein NEDD8 ultimate buster 1 (NUB1) negatively regulates the NEDD8 conjugation system and recruits both NEDD8- and FAT10-conjugated proteins to the proteasome for degradation [29]. NUB1 exhibits growth-inhibitory properties and induces apoptosis in cancer cells, particularly in renal cell carcinoma [29].

Beyond oncology, UBL pathways are being investigated as therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative disorders and cardiac diseases [25] [26]. In cardiovascular pathology, insufficient ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis contributes to the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates in cardiomyocytes, while modulation of SUMOylation and NEDD8 pathways affects cardiac hypertrophy and ischemic injury [26].

Diagram: Therapeutic Strategies for Targeting Dysregulated UBL Pathways. Multiple intervention points exist for correcting aberrant UBL signaling, including E1 inhibition, disruption of E2-E3 interactions, modulation of deconjugating enzymes, and enhancement of natural negative regulators like NUB1.

The major UBL families—SUMO, NEDD8, ISG15, ATG8, and ATG12—represent crucial regulatory systems that expand the functional capacity of the proteome through reversible protein modification. Each UBL pathway employs a conserved enzymatic cascade while maintaining specificity through dedicated enzymes and regulatory mechanisms. Continued advances in research tools, particularly proteomic platforms like the bioUbL system and highly specific inhibitors, are accelerating our understanding of these complex pathways. The therapeutic targeting of UBL systems in cancer and other diseases highlights the translational importance of fundamental research in this field. As our knowledge of UBL structure, function, and regulation expands, so too will opportunities for manipulating these pathways for therapeutic benefit.

The ubiquitin-like protein (UBL) system, a hallmark of eukaryotic cellular regulation, did not originate de novo but evolved from ancient prokaryotic precursors. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence demonstrating that UBLs and their conjugation machinery originated from sulfur carrier systems and enzyme cofactor biosynthesis pathways present in the last universal common ancestor (LUCA). Structural and phylogenetic analyses reveal that modern UBLs, including ubiquitin itself, evolved from the β-grasp fold (β-GF) that initially functioned in RNA binding and sulfur transfer in prokaryotic metabolic pathways. The conservation of this structural architecture over billions of years, coupled with its functional diversification from basic metabolic roles to sophisticated regulatory signaling, represents a remarkable evolutionary trajectory. Understanding these origins provides critical insights for drug development targeting UBL pathways in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and autoimmune disorders.

Ubiquitin-like proteins constitute a family of protein modifiers that regulate virtually every aspect of eukaryotic cellular function through post-translational modification of target proteins. The canonical ubiquitin protein comprises 76 amino acids and adopts a compact globular structure characterized by a central α-helix embraced by five β-strands, forming the distinctive β-grasp domain [31] [32]. This structural motif is shared across UBLs, despite considerable sequence divergence among family members.

The UBL conjugation system operates through a conserved enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [32] [33]. This system facilitates the covalent attachment of UBLs to target proteins, modulating their activity, stability, localization, and interactions. The human genome encodes numerous UBLs, including SUMO, NEDD8, ATG8, ATG12, URM1, UFM1, Ubl5/Hub1, FUB1, FAT10, and ISG15, each with specialized cellular functions [31]. The evolutionary transformation of this system from prokaryotic metabolic functions to eukaryotic regulatory roles represents one of the most significant developments in cellular evolution.

Structural Conservation and the β-Grasp Fold

The Ubiquitin Superfold

The β-grasp fold represents an ancient structural motif that predates the divergence of prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Comprehensive structural analyses indicate that the β-GF differentiated into at least seven distinct clades by the time of LUCA, encompassing much of the structural diversity observed in modern versions [13]. This fold is characterized by a five-strand β-sheet (five antiparallel β-strands) and a single α-helix at the apex, forming a compact globular domain that has been recruited for strikingly diverse biochemical functions [31] [13].

Table 1: Diversity of β-Grasp Fold Functions Across Evolution

| Organismal Domain | Representative Functions | Example Proteins/Domains |

|---|---|---|

| Prokaryotes | Catalytic roles, RNA binding, sulfur transfer, co-factor binding | NUDIX hydrolases, MoaD, ThiS, Molybdopterin synthases |

| Eukaryotes | Protein modification, signaling, autophagy, immune response | Ubiquitin, SUMO, NEDD8, ATG8, ATG12 |

| Universal | Scaffolding iron-sulfur clusters, mediation of protein interactions | Various UDPs (Ubiquitin-like Domain Proteins) |

Structural Phylogeny of UBLs

The structural conservation between prokaryotic sulfur carriers and eukaryotic UBLs provides compelling evidence for their evolutionary relationship. Solution NMR structure of Urm1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae has revealed it as a unique "molecular fossil" that preserves the most conserved structural and sequence features of the common ancestor of the entire ubiquitin superfamily [34]. Striking similarities in 3D structure and hydrophobic and electrostatic surface features exist between Urm1 and MoaD (molybdopterin synthase small subunit), suggesting they interact with partners in analogous manners [34].

The structural resemblance extends beyond individual proteins to functional complexes. Notably, similarities between the Urm1-Uba4 and MoaD-MoeB pairs establish an evolutionary link between ATP-dependent protein conjugation in eukaryotes and ATP-dependent cofactor sulfuration in prokaryotes [34]. This connection reveals how the eukaryotic UBL system co-opted existing structural frameworks from prokaryotic metabolic pathways.

Evolutionary Trajectory from Prokaryotic Systems

Origins in Sulfur Transfer and Cofactor Biosynthesis

The evolutionary origin of UBL conjugation systems can be traced to prokaryotic pathways involved in sulfur transfer and enzyme cofactor biosynthesis. Comparative genomic analyses indicate that precursors of the eukaryotic Ub-system were already present in prokaryotes, with the most basic versions combining a Ubl and an E1-like enzyme involved in metabolic pathways related to metallopterin, thiamine, cysteine, siderophore, and modified base biosynthesis [13]. These primordial systems primarily functioned in the biosynthesis of essential enzyme cofactors through sulfur transfer mechanisms.

The Urm1 pathway represents a particularly significant evolutionary link, as it shares characteristics with both prokaryotic sulfur carrier systems and modern eukaryotic UBL pathways. Urm1 is involved in both thiolation of transfer RNAs and protein conjugation, serving as a functional bridge between these distinct biochemical processes [34]. This dual functionality provides a plausible evolutionary pathway for the transition from metabolic to regulatory functions.

Development of Conjugation Machinery

The evolution of the complete UBL conjugation machinery (E1-E2-E3) occurred through a process of gene duplication, fusion, and functional specialization. Prokaryotic systems containing Ubls of the YukD and other families, including some very close to Ub itself, developed additional elements that more closely resemble the eukaryotic state in possessing an E2 conjugating enzyme, a RING-type E3 ligase, or both [13]. These findings demonstrate that the fundamental components of the UBL system were already emerging in prokaryotic lineages.

Table 2: Evolutionary Development of UBL Conjugation Machinery

| Evolutionary Stage | Key Components | Functional Capabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Primordial Prokaryotic | Ubl + E1-like enzyme | Sulfur transfer for cofactor biosynthesis |

| Intermediate Prokaryotic | Ubl + E1 + E2/E3 elements | Limited protein modification |

| Early Eukaryotic | Multiple UBL families + E1-E2-E3 cascade | Diverse protein tagging functions |

| Modern Eukaryotic | Expanded UBL families + Complex E3 ligases | Sophisticated regulatory networks |

The evolutionary trajectory involved both the conservation of a universal structural fold of UBLs and the rise in complexity of the superfamily of ligases that conjugate UBLs to substrates. This complexity increased in terms of the number of enzyme variants, structural organization diversity, and diversification of catalytic domains [31]. The E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes of metazoan phyla are highly conservative, whereas the homology of E3 ubiquitin ligases with human orthologues gradually decreases depending on evolutionary distance and "molecular clock" timing [31].

Experimental Approaches for Studying UBL Evolution

Structural Biology Techniques

Solution NMR Spectroscopy has been instrumental in elucidating the evolutionary relationships between UBLs and prokaryotic sulfur carriers. The protocol for determining the solution structure of Urm1 involved:

- Protein Expression and Purification: Recombinant Urm1 was expressed in E. coli and purified using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

- NMR Data Collection: A comprehensive set of NMR experiments including (^1\text{H})-(^{15}\text{N}) HSQC, (^1\text{H})-(^{13}\text{C}) HSQC, HNCA, HNCOCA, HNCACB, and CBCACONH were performed to obtain backbone and side-chain assignments.

- Structure Calculation: Distance constraints from NOESY spectra combined with torsion angle constraints were used to calculate the three-dimensional structure using simulated annealing protocols in programs such as X-PLOR or CYANA.

- Structural Comparison: The solved structure was compared with known structures of prokaryotic sulfur carriers (e.g., MoaD) and other UBLs using structural alignment algorithms like DALI or VAST.

X-ray Crystallography has provided additional insights into the structural conservation of the β-grasp fold across evolution. Recent structural studies of E1 enzymes have revealed their conserved architecture and the dynamic changes that accompany UBL activation and transfer [32]. These structures build upon foundational biochemical research to elucidate the determinants of activity, specificity, and novel regulatory mechanisms governing UBL conjugation.

Phylogenomic Analysis

Comparative Genomics approaches have been essential for tracing the evolutionary history of UBL systems:

- Sequence Database Mining: Iterative BLAST searches using known UBLs and conjugation enzymes as queries against diverse taxonomic groups.

- Profile-based Methods: Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and PSI-BLAST to detect distant homologs that may have diverged significantly in sequence while retaining structural and functional similarity.

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Multiple sequence alignment of identified homologs followed by maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference methods to reconstruct evolutionary relationships.

- Synteny Analysis: Examination of genomic context and conservation of gene neighborhoods to identify functional associations and evolutionary events.

These methods have revealed that the β-grasp fold first emerged in the context of translation-related RNA-interactions and subsequently diversified to occupy various functional niches [13]. Most biochemical diversification of the fold occurred in prokaryotes, with the eukaryotic phase of its evolution mainly marked by the expansion of the Ubl clade of the β-GF [13].

Biochemical and Functional Assays

Enzyme Kinetics Studies have been crucial for understanding the mechanistic evolution of UBL activation. Foundational biochemical research revealed that activation of ubiquitin follows a pseudo-ordered substrate binding mechanism, where ATP-Mg(^{2+}) preferentially binds first, followed by ubiquitin [32]. Kinetic analysis of thioester formation, combined with site-directed mutagenesis of conserved residues like Asp576 in human UBA1, has demonstrated this preferential binding and provided insights into the evolution of enzyme specificity.

In Vitro Reconstitution Assays have allowed researchers to test the functional capabilities of putative ancestral UBL systems. These experiments typically involve:

- Purified Component Incubation: Combining recombinant UBL, E1, E2, and E3 enzymes with ATP and potential substrate proteins.

- Reaction Monitoring: Using techniques like western blotting, mass spectrometry, or fluorescence-based assays to detect UBL conjugation.

- Cross-species Complementation: Testing whether components from evolutionarily distant organisms can function together, providing evidence for conserved mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating UBL Evolution

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Evolutionary Insight Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | Urm1, MoaD, ThiS, MoeB | Structural comparison, biochemical assays | Reveals conserved structural features and functional mechanisms |

| Antibodies | Anti-ubiquitin, anti-SUMO, anti-Urm1 | Detection of UBL conjugates in diverse organisms | Identifies conservation of modification patterns across species |

| NMR Isotope Labels | (^{15}\text{NH}_4\text{Cl}), (^{13}\text{C})-glucose | Protein structure determination | Enables atomic-level structural comparisons between modern and ancestral forms |

| Phylogenetic Software | MEGA, PhyML, RAxML | Evolutionary tree construction | Reconstructs evolutionary relationships and divergence times |

| Structural Alignment Tools | DALI, VAST, PyMOL | 3D structure comparison | Quantifies structural conservation despite sequence divergence |

| Activity-Based Probes | HA-Ub-VS, SUMO-AMC | Enzyme activity profiling | Traces functional conservation of conjugation machinery |

Implications for Human Disease and Therapeutic Development

The evolutionary perspective on UBL systems provides valuable insights for drug development targeting these pathways in human disease. The high conservation of UBL components from prokaryotes to humans validates their fundamental importance in cellular function and supports their relevance as therapeutic targets. Dysregulation of UBL pathways has been implicated in diverse pathological conditions, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, autoimmune disorders, and developmental syndromes [32] [33].

The E1 enzymes that initiate UBL activation have emerged as particularly attractive therapeutic targets. As the gatekeepers of UBL cascades, E1s represent potential choke points for pharmacological intervention. Current research is exploring E1 inhibitors as potential anticancer therapies, leveraging the evolutionary conservation of their catalytic mechanisms while exploiting structural differences for specificity [32]. Understanding the evolutionary origins of these enzymes provides a framework for predicting potential side effects and assessing conservation across therapeutic models.

Neurodegenerative diseases exemplify the pathological consequences of UBL system dysfunction. Reduced expression of UBA1, the major E1 enzyme for ubiquitin, has been reported in Huntington's disease, while rare missense mutations that impair UBA1 function cause X-linked infantile spinal muscular atrophy [32]. The essential nature of UBA1 is evidenced by the embryonic lethality of complete knockout in mice, highlighting the critical role of this evolutionarily ancient enzyme in neuronal health [32].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

Several promising research directions emerge from our current understanding of UBL evolution: