Ubiquitinomics vs Proteomics: The Next Frontier in Cancer Biomarker Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between ubiquitinomics and proteomics for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in cancer biomarker discovery.

Ubiquitinomics vs Proteomics: The Next Frontier in Cancer Biomarker Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between ubiquitinomics and proteomics for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in cancer biomarker discovery. We explore the foundational principles of both fields, detailing how traditional proteomics delivers a broad snapshot of protein expression while ubiquitinomics specifically deciphers the dynamic ubiquitin code—a key regulator of protein stability and function implicated in tumorigenesis. The content examines current methodological approaches, from mass spectrometry and antibody-based techniques to innovative aptamer technologies, addressing critical challenges like tumor heterogeneity and analytical sensitivity. Through comparative analysis and validation frameworks, we demonstrate how integrating these complementary disciplines enables the identification of clinically actionable biomarkers for early detection, patient stratification, and personalized cancer therapeutics.

From Static Proteomes to Dynamic Modifications: Understanding Cancer's Molecular Landscape

In the pursuit of personalized cancer medicine, the large-scale study of cellular proteins, or proteomics, provides a comprehensive portrait of the molecular drivers of disease [1] [2]. It aims to characterize the entire complement of proteins, or proteome, which is dynamic and varies from cell to cell, reflecting the real-time functional state of a biological system [2]. By contrast, ubiquitinomics is a specialized sub-discipline that focuses specifically on the ubiquitin-modified subset of the proteome, known as the ubiquitinome [3] [4]. Ubiquitination is a post-translational modification (PTM) where a small protein, ubiquitin, is covalently attached to lysine residues on substrate proteins, fundamentally altering their fate [3]. This modification is a dynamic process, orchestrated by E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes, and reversed by deubiquitinases (DUBs) [3]. While proteomics offers a global view, ubiquitinomics delivers a focused investigation into a key regulatory mechanism that controls protein stability, localization, and activity, offering a unique lens through which to view cancer pathophysiology [5] [4].

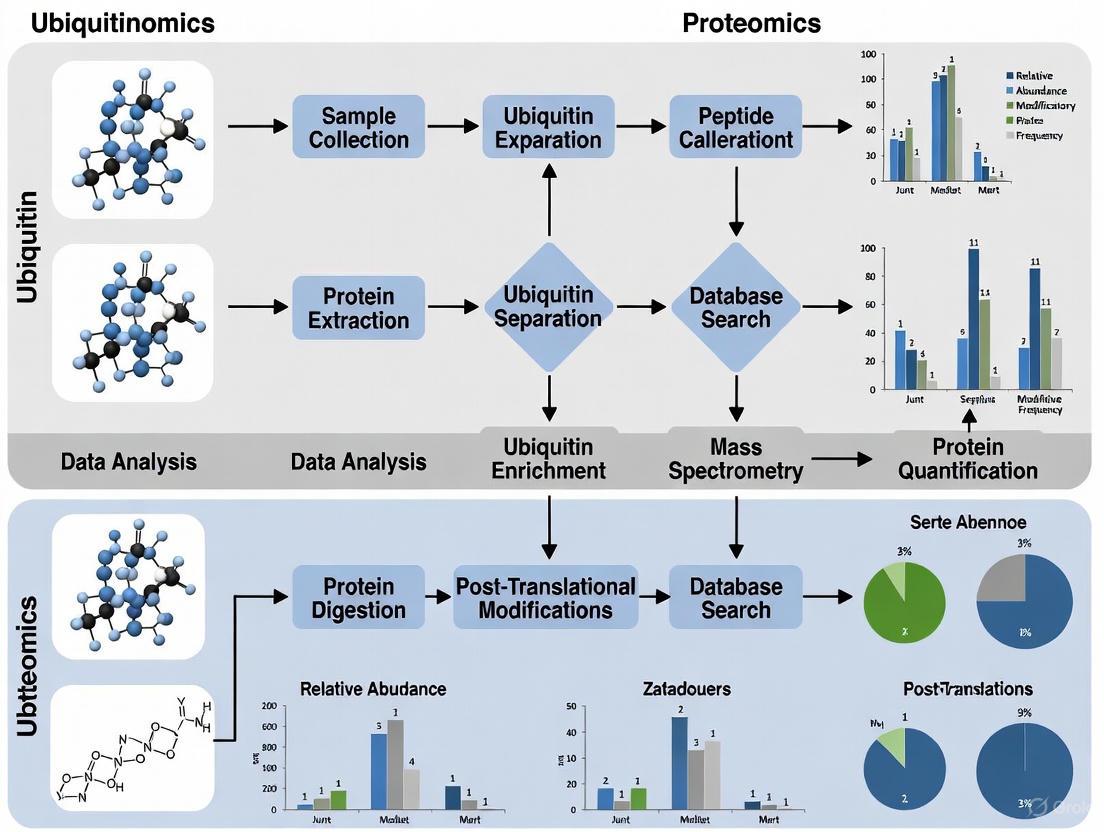

The following diagram illustrates the core focus and relationship between these two fields.

Figure 1: The Scope of Proteomics and Ubiquitinomics. Proteomics studies the entire proteome, while ubiquitinomics focuses on the ubiquitinome, a specific, modified subset of proteins.

Core Principles and Analytical Techniques

The Broad View of Proteomics

The fundamental goal of proteomics is the large-scale identification and quantification of proteins expressed by a genome [2]. This field acknowledges that the proteome is far more complex than the genome due to factors like alternative splicing, a vast dynamic range of protein abundances, and extensive post-translational modifications [2]. Proteomic technologies have been driven largely by advances in mass spectrometry (MS) [2]. Two primary strategies are employed:

- Gel-based proteomics: This mature approach involves separating complex protein mixtures using high-resolution two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DE), followed by excising protein spots of interest for identification by MS [2].

- Gel-free proteomics: This strategy often involves digesting proteins into peptides, which are then separated by liquid chromatography (LC) and directly analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [1]. Methods like iTRAQ (Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation) use isotopic tags to enable multiplexed quantification of proteins across different samples [6].

The Focused Lens of Ubiquitinomics

Ubiquitinomics is defined by its precise focus on mapping and quantifying ubiquitination events. The complexity of ubiquitin signaling is immense, as proteins can be modified by a single ubiquitin (monoubiquitination), multiple single ubiquitins (multiubiquitination), or chains of ubiquitin (polyubiquitination) linked through any of its seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63), each potentially conferring a distinct functional consequence [3]. The primary challenge is the low stoichiometry of this modification; for any given protein, only a small fraction may be ubiquitinated at any time [3] [4].

To overcome this, enrichment strategies are critical prior to MS analysis. The most common method leverages the fact that trypsin digestion of ubiquitinated proteins leaves a characteristic di-glycine (Gly-Gly) remnant on the modified lysine. Antibodies specific for this K-ε-GG motif are used to immuno-enrich ubiquitinated peptides from complex digests, dramatically improving the detection of these low-abundance species [3] [4]. Quantitative techniques like SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino acids in Cell culture) are then applied to compare ubiquitination sites across different conditions, such as before and after proteasome inhibition, to infer function [4].

Table 1: Core Conceptual and Methodological Comparison

| Feature | Proteomics | Ubiquitinomics |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Focus | The entire proteome (all proteins) [2] | The ubiquitinome (ubiquitin-modified proteins) [3] [4] |

| Primary Objective | Protein identification, expression profiling, and quantification [2] | Mapping ubiquitination sites, identifying substrates, and characterizing chain topology [3] |

| Key Complexity | Vast dynamic range of protein concentrations; multiple PTMs [2] | Tremendous diversity of ubiquitin modifications (mono/poly, chain linkages) [3] |

| Core Enrichment Strategy | Pre-fractionation by 2DE or LC [2] | Immunoaffinity enrichment of K-ε-GG remnant peptides [3] [4] |

| Common Quantification Methods | iTRAQ, label-free spectral counting [6] [7] | SILAC, label-free based on enrichment [4] |

Application in Cancer Biomarker Discovery: A Comparative Outlook

Both fields hold immense promise for uncovering novel cancer biomarkers, but they illuminate different aspects of tumor biology.

Proteomics excels at discovering protein expression signatures associated with cancer. For instance, in gastric cancer, iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of saliva revealed S100A8, S100A9, CST4, and CST5 as potential non-invasive biomarkers for detection [6]. Similarly, profiling tumor tissue-derived proteomes can identify panels of proteins, such as Vimentin (VIM) and Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP), with differential abundance across colon, kidney, liver, and brain cancers, useful for multi-class cancer distinction [7]. The strength of proteomics lies in its unbiased nature, capable of revealing unanticipated biology and providing a snapshot of the functional state of a tumor [8].

Ubiquitinomics, by contrast, investigates the dysregulation of protein stability and signaling in cancer. The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is critically involved in the pathogenesis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), where ubiquitination regulates the stability of key oncoproteins and tumor suppressors like EGFR, p53, and PD-L1 [5]. For example, the deubiquitinating enzyme USP21 stabilizes the oncoprotein AURKA by removing its ubiquitin mark, thereby promoting laryngeal cancer progression [9]. Biomarkers derived from ubiquitinomics are not just about protein abundance but about the post-translational status of critical regulatory nodes. A transcriptomics-based study in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LSCC) identified a panel of four ubiquitination-related biomarkers (WDR54, KAT2B, NBEAL2, LNX1), providing insights into molecular mechanisms and potential diagnostic utility [9].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis in Cancer Biomarker Discovery

| Aspect | Proteomics | Ubiquitinomics |

|---|---|---|

| Biomarker Type | Protein abundance signatures and proteoforms [8] [6] | Ubiquitination status of specific substrate proteins [5] [9] |

| Biological Insight | Functional state and phenotypic output of the cell/tumor [2] | Dysregulation of specific signaling pathways and protein turnover [3] [5] |

| Sample Types | Tissue, plasma, saliva, other biofluids [8] [6] | Primarily tissue, but applicable to biofluids with enrichment |

| Therapeutic Link | Identifies over/under-expressed proteins for targeting [1] | Directly identifies druggable E3 ligases and DUBs (e.g., PROTACs) [5] |

| Example Biomarkers | S100A8, S100A9 in gastric cancer saliva [6] | Ubiquitination-related WDR54, KAT2B in LSCC [9] |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

A Typical Proteomics Workflow for Biomarker Discovery (Saliva)

A standard protocol for biomarker discovery using iTRAQ and PRM in saliva involves [6]:

- Sample Collection & Preparation: Collect unstimulated saliva and centrifuge to remove cells and debris. Store the supernatant at -80°C.

- Protein Digestion and Labeling: Reduce, alkylate, and digest proteins with trypsin. Label the resulting peptides from different sample groups (e.g., cancer vs. control) with different iTRAQ tags.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Pool the labeled peptides and separate them using liquid chromatography. Analyze the eluting peptides with a tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS) to acquire both identification and quantitative data.

- Data Analysis & Validation: Identify proteins and calculate differential expression based on iTRAQ reporter ions. Select candidate biomarkers and validate them in a separate cohort of samples using a targeted MS method like Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) for high-confidence quantification.

The overall workflow from sample to discovery and validation is summarized below.

Figure 2: Proteomics Biomarker Workflow. Key steps from sample preparation to biomarker validation.

A Ubiquitinomics Workflow for Functional Signaling Analysis

A detailed protocol for analyzing ubiquitin signaling, particularly in response to proteasome inhibition, includes [4]:

- SILAC Labeling and Treatment: Culture two populations of cells in "light" (normal) and "heavy" (isotope-labeled) media. Treat the light cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132) and the heavy cells with a vehicle control (DMSO).

- Cell Lysis and Mixing: Lyse both cell populations and mix the light and heavy lysates in a 1:1 protein ratio.

- Trypsin Digestion and Enrichment: Digest the combined protein sample with trypsin. Use anti-K-ε-GG antibody beads to specifically enrich for ubiquitinated peptides from the complex peptide mixture.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis and Data Interpretation: Fractionate the enriched peptides and analyze by LC-MS/MS. The MS data will identify the ubiquitination site and the SILAC ratio will indicate changes in ubiquitin occupancy at that site. An increase in the light/heavy ratio (MG132/DMSO) suggests the site is involved in degradation signaling, as its occupancy increases when the proteasome is blocked.

This functional ubiquitinomics workflow is illustrated as follows.

Figure 3: Functional Ubiquitinomics Workflow. Quantitative workflow using SILAC and enrichment to study ubiquitin signaling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful proteomics and ubiquitinomics studies rely on a suite of specialized reagents and platforms.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent / Platform | Function | Field of Use |

|---|---|---|

| iTRAQ / TMT Tags | Isobaric chemical tags for multiplexed relative and absolute quantification of peptides in MS-based experiments. [6] | Proteomics |

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody | Monoclonal antibody for immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides from tryptic digests. [3] [4] | Ubiquitinomics |

| SILAC Media | Cell culture media containing stable isotope-labeled essential amino acids (e.g., 13C6-Lysine) for metabolic labeling and quantitative MS. [4] | Proteomics / Ubiquitinomics |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Bortezomib) | Small molecules that block the 26S proteasome, used to perturb the ubiquitin-proteasome system and stabilize ubiquitinated proteins. [5] [4] | Ubiquitinomics |

| Proteograph / Nanoparticle Platforms | Proprietary engineered nanoparticles to overcome the dynamic range problem in plasma proteomics by deeply profiling biofluits. [8] | Proteomics |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (e.g., Orbitrap Astral) | Advanced MS instrumentation providing the high speed, sensitivity, and resolution needed for large-scale protein and PTM identification. [8] | Proteomics / Ubiquitinomics |

Proteomics and ubiquitinomics are not competing but complementary forces in the battle against cancer. Proteomics provides the essential, wide-angle battlefield assessment, mapping the entire protein landscape to identify altered territories in disease. Ubiquitinomics, in contrast, offers a high-power lens on the precise molecular machinery controlling the fate of key proteins. The future of biomarker discovery lies in the integration of these approaches, layering global protein expression data with deep knowledge of ubiquitin-regulated pathways. This synergy, especially when combined with other omics data and powered by AI, will accelerate the development of robust diagnostic panels and reveal novel, druggable targets within the ubiquitin-proteasome system, such as PROTACs, ultimately paving the way for more effective precision oncology therapies [8] [5].

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a master regulatory network that governs oncogenesis through precise control of protein stability and function. This review examines how dysregulation of ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation drives cancer pathogenesis, exploring the comparative utility of ubiquitinomics and proteomics for biomarker discovery. We synthesize evidence from multiple malignancies—including breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancers—to illustrate UPS alterations across cancer types. The analysis incorporates quantitative ubiquitinome profiles, experimental methodologies for UPS interrogation, and emerging therapeutic strategies that target this sophisticated regulatory system. By integrating large-scale ubiquitinomic datasets with functional proteomics, this work establishes a framework for understanding UPS-mediated oncogenic pathways and identifies promising directions for diagnostic and therapeutic development.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system constitutes the primary pathway for controlled intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, regulating approximately 80-90% of cellular proteins [10]. This sophisticated system operates through a sequential enzymatic cascade: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1) initiate the process, ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2) intermediate the transfer, and ubiquitin ligases (E3) provide substrate specificity, ultimately tagging target proteins with ubiquitin chains for recognition and degradation by the 26S proteasome [11]. The specificity of this system is remarkable, with humans encoding only two E1 enzymes, approximately 35 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases that confer precise substrate recognition [10].

Figure 1: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Protein Degradation Pathway

In cancer biology, the UPS functions as a critical master regulator of oncogenic pathways through its governance of key proteins involved in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, DNA repair, and signal transduction [12] [10]. Malignant transformation frequently co-opts UPS components to stabilize oncoproteins, eliminate tumor suppressors, and activate proliferative signaling pathways. The clinical relevance of targeting this system was established with the FDA approval of proteasome inhibitors for multiple myeloma, validating the UPS as a legitimate therapeutic target in oncology [11].

Ubiquitinomics vs. Proteomics: Comparative Approaches for Biomarker Discovery

The emergence of ubiquitinomics—the large-scale study of ubiquitin-modified proteins—represents a technological advancement that complements traditional proteomics in cancer research. While conventional proteomics quantifies protein abundance, ubiquitinomics specifically maps ubiquitination sites and measures ubiquitin occupancy, providing deeper functional insights into protein regulation.

Table 1: Comparison of Proteomic and Ubiquitinomic Approaches in Cancer Research

| Parameter | Proteomics | Ubiquitinomics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Protein identification and quantification | Mapping ubiquitination sites and ubiquitin occupancy |

| Key Metrics | Protein abundance, expression changes | Ubiquitin stoichiometry, site-specific occupancy changes |

| Technical Methods | LC-MS/MS, SILAC, label-free quantification | Ubiquitin remnant motif enrichment (K-ε-GG), SILAC with proteasome inhibition |

| Biological Insights | Protein expression patterns, pathway activation | Protein degradation signaling, regulatory mechanisms |

| Cancer Applications | Biomarker identification, molecular subtyping | Therapeutic target discovery, resistance mechanism elucidation |

| Sample Throughput | High (global profiling) | Moderate (requires enrichment) |

| Data Output | 4,000-6,000 proteins (typical study) | 1,500-2,500 ubiquitination sites (typical study) |

The integration of these complementary approaches generates a more comprehensive understanding of cancer pathophysiology. For instance, proteomic analyses of colorectal cancer tissues have identified approximately 4,712 quantifiable proteins, while parallel ubiquitinomic examinations characterized 1,690 quantifiable ubiquitination sites across 870 proteins [13]. This integrated profiling revealed that highly ubiquitinated proteins (containing ≥10 modification sites) are particularly enriched in biological processes including G-protein coupling, antigen presentation, and metabolic regulation.

Table 2: Experimentally Identified Ubiquitination Sites Across Cancers

| Cancer Type | Total Ubiquitination Sites Identified | Key Regulated Biological Processes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | 1,690 sites across 870 proteins | Metabolic regulation, immune function, telomere maintenance | [13] |

| Prostate Cancer | 248 UPS-related genes with differential expression | Cell cycle progression, TNF response, immune signaling | [14] |

| Ovarian Cancer | Multiple novel HER2 ubiquitination sites | Receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, degradation vs. non-degradation signaling | [4] |

| Breast Cancer | Over-expression of 5 proteasome subunits | Protein degradation, stress response, growth regulation | [15] |

Experimental Methodologies: Deciphering the Ubiquitin Code

Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Enrichment and Proteomic Analysis

The foundational methodology for ubiquitinome mapping relies on the specific enrichment of ubiquitin-modified peptides following tryptic digestion. This approach capitalizes on the characteristic diglycine (K-ε-GG) "remnant" that remains attached to modified lysine residues after trypsinization. The standard workflow encompasses:

- Cell Culture and Proteasome Inhibition: SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells cultured in heavy SILAC media are treated with 20μM MG132 proteasome inhibitor for 6 hours to accumulate ubiquitinated substrates [4].

- Protein Extraction and Digestion: Cells are lysed in 8M urea buffer, reduced with TCEP, alkylated with iodoacetamide, and digested with trypsin overnight at 25°C using a 1:50 enzyme-to-substrate ratio [4] [13].

- Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment: Digested peptides are subjected to immunoaffinity purification using PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit, which specifically recognizes the K-ε-GG motif [4].

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry: Enriched peptides are separated using nanoflow liquid chromatography with a 60-minute acetonitrile gradient (6-80% mobile phase B) and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry with parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation (PASEF) detection [13].

- Data Processing and Stoichiometry Calculation: MS data are processed using MaxQuant against the UniProt human database, with ubiquitin occupancy calculated by comparing heavy and light peptide ratios [4].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitinomics Profiling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin-Proteasome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Block degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, enable accumulation for analysis |

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Kits | PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit | Immunoaffinity purification of K-ε-GG modified peptides |

| Mass Spectrometry Labels | SILAC (13C6-15N4-L-Arg, 13C6-L-Lys) | Metabolic labeling for quantitative proteomics |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | PR-619, VLX1570 | Inhibit DUB activity to preserve ubiquitin chains |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | Molecular glues (Lenalidomide), PROTACs | Targeted protein degradation for functional studies |

| Antibodies for Validation | Anti-ubiquitin, anti-K-ε-GG | Western blot, immunohistochemistry validation |

UPS Dysregulation Across Cancer Types: Ubiquitinome Profiles

Breast Cancer: Proteasomal Overactivation

Comprehensive analyses of breast cancer tissues reveal significant overexpression of multiple UPS components compared to adjacent normal tissue. RFDD-PCR and proteomic methodologies identified 3- to 32-fold increases in proteasomal activity and specific subunits, including:

- PSMB5, PSMD1, PSMD2, PSMD8, PSMD11: Proteasome subunits showing >3-fold overexpression [15]

- USP9X, USP9Y, USP10, USP25: Ubiquitin-specific peptidases with significant overexpression [15]

- UBE3A: Ubiquitin protein ligase demonstrating marked overexpression, validated by immunohistochemistry [15]

This enhanced proteasomal capacity enables breast cancer cells to rapidly degrade tumor suppressors and cell cycle regulators, facilitating uncontrolled proliferation and therapeutic resistance.

Prostate Cancer: Stage-Specific Ubiquitination Signatures

Ubiquitin-proteasome pathway-linked gene signatures provide prognostic indicators in prostate cancer, with distinct expression patterns across disease stages:

Early-Stage (pT3a/Gleason 3+4) Alterations:

- Upregulated: IKBKB (1.34-fold), UBQLN3 (6.0-fold), BRCA1 (1.24-fold) [14]

- Downregulated: TMUB2 (0.87-fold), UBE2S (0.68-fold) [14]

- Pathway Enrichment: Cellular response to tumor necrosis factor (GO:0071356) [14]

Advanced-Stage (pT3b/Gleason 4+3) Alterations:

- Upregulated: CDC20 (4.43-5.02-fold), UHRF1 (3.21-4.04-fold), UBE2C, UBE3C [14]

- Downregulated: HERPUD1 (0.52-0.56-fold) [14]

Metastatic-Stage (pT4/Gleason ≥8) Alterations:

A LASSO-Cox prognostic model identified six genes (LNX1, PSMD2, SUMO4, UBE2C, UBR5, UHRF1) with significant predictive value for biochemical recurrence-free survival [14].

Colorectal Cancer: Survival-Associated Ubiquitination Events

Ubiquitinomic profiling of colorectal cancer tissues identified 1,172 proteins with upregulated ubiquitination and 1,700 with downregulated ubiquitination compared to normal adjacent tissues [13]. Key findings include:

- Highly Ubiquitinated Proteins: PRKDC (49 ubiquitination sites), PARP14, SLC12A2, and SPG10 demonstrated exceptionally high ubiquitination site numbers (≥10 sites) [13]

- Motif Analysis: Five distinct ubiquitin recognition motifs were identified, suggesting specific E3 ligase preferences [13]

- Survival Correlation: Increased ubiquitination of FOCAD at Lys583 and Lys587 was potentially associated with patient survival outcomes [13]

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): Ubiquitination in Therapeutic Resistance

The UPS plays a significant role in NSCLC pathogenesis and resistance to targeted therapies:

- EGFR Regulation: WDR4-Cul4 complex inhibits PTPN23-mediated EGFR degradation, while USP22 stabilizes EGFR [5]

- KRAS Pathway: USP5 stabilizes Beclin1 to promote p53 degradation, while OTUD7B modulates mTORC2 complexes [5]

- Immune Checkpoints: Multiple USP family members (USP7, USP8, USP22) precisely regulate PD-L1 stability, influencing immune evasion [5]

Therapeutic Targeting of the UPS: From Inhibition to Targeted Degradation

Established Modalities: Proteasome Inhibitors

The clinical success of proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma validates the UPS as a therapeutic target. These inhibitors include:

- Bortezomib: First-in-class proteasome inhibitor targeting the chymotrypsin-like activity of the 20S proteasome [12] [10]

- Carfilzomib: Second-generation epoxyketone inhibitor with irreversible binding characteristics [11]

- Ixazomib: Oral proteasome inhibitor with improved convenience [11]

Despite their efficacy in hematological malignancies, proteasome inhibitors have demonstrated limited clinical utility in solid tumors, prompting development of more targeted approaches [12].

Emerging Strategies: Targeted Protein Degradation

PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras): Heterobifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target specific proteins for degradation. These consist of:

Molecular Glue Degraders: Small molecules that induce neomorphic interactions between E3 ligases and target proteins, exemplified by:

- Immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs): Thalidomide, lenalidomide, pomalidomide that recruit CRL4CRBN to degrade transcription factors IKZF1/IKZF3 [16]

- Novel CRBN recruiters: Phenyl glutarimide-based degraders targeting neosubstrates including KDM4B, G3BP2, and VCL [16]

High-throughput proteomic screening of CRBN ligands has identified degraders with exquisite selectivity for previously uncharacterized neosubstrates, substantially expanding the druggable proteome [16].

Combinatorial Approaches: UPS Inhibition with Epigenetic Modulators

Preclinical evidence supports combination therapies targeting both UPS and epigenetic pathways:

- HDAC inhibitors + Proteasome inhibitors: Enhanced apoptosis in solid cancer models [12]

- DNMT inhibitors + UPS targeting: Synergistic effects in hematological malignancies [12]

- Dual-pathway targeting: Potential for reduced adverse effects compared to standard chemotherapeutics [12]

The ubiquitin-proteasome system unquestionably functions as a master regulator of cancer pathways, governing protein stability, function, and abundance across virtually all oncogenic processes. The integration of ubiquitinomics with traditional proteomics provides unprecedented insights into the regulatory mechanisms driving cancer pathogenesis, offering:

- Novel Biomarkers: Site-specific ubiquitination signatures with prognostic and predictive value

- Therapeutic Targets: Identification of dysregulated E3 ligases and DUBs for targeted intervention

- Resistance Insights: Elucidation of post-translational mechanisms underlying treatment failure

- Combinatorial Strategies: Rational design of synergistic treatment approaches

As ubiquitinomic technologies continue to advance—with improved enrichment strategies, quantitative accuracy, and computational analysis—their integration with functional proteomics will undoubtedly yield transformative insights into cancer biology and therapeutic development. The ongoing refinement of UPS-targeting agents, particularly molecular glues and PROTACs, promises to expand the druggable proteome and overcome limitations of conventional therapeutics. Through continued mapping of the cancer ubiquitinome and its functional integration with proteomic signatures, we move closer to realizing the promise of precision oncology for diverse cancer types.

The pursuit of cancer biomarkers has evolved from a singular focus on expression levels to a more nuanced understanding of protein function. While traditional proteomics provides a quantitative map of the proteome, it often overlooks functional alterations that drive tumorigenesis. Ubiquitinomics, a specialized branch of proteomics that characterizes protein ubiquitination, addresses this gap by capturing crucial functional information about protein regulation, stability, and activity. This guide objectively compares the capabilities of ubiquitinomics and conventional proteomics in biomarker discovery, demonstrating through experimental data how analyzing protein function provides deeper biological insights and more clinically relevant discoveries than expression analysis alone.

In classical proteomics, the primary objective has been to identify and quantify protein expression changes between normal and diseased states. However, cancer biology is driven not merely by which proteins are present, but by how they function. Protein function encompasses catalytic activity, protein-protein interactions, localization, and post-translational modifications (PTMs) that collectively determine biological outcomes. The limitation of mere expression analysis becomes particularly evident when considering that proteins with unchanged abundance may undergo functional alterations through mutations or PTMs that fundamentally change their activity [17].

Ubiquitinomics represents a functional proteomics approach that systematically studies the ubiquitin code—a complex post-translational modification system that regulates protein degradation, signaling, and localization. Unlike conventional proteomics that answers "how much" of a protein exists, ubiquitinomics addresses "what happens to" proteins in the cancer environment, providing critical insights into the functional rewiring of cellular pathways in tumorigenesis [18].

Comparative Analysis: Ubiquitinomics vs. Conventional Proteomics

Table 1: Technical and Analytical Comparison between Proteomics and Ubiquitinomics

| Parameter | Conventional Proteomics | Ubiquitinomics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Protein identification and quantification | Ubiquitin-modified protein analysis |

| Information Gained | Expression levels, abundance changes | Protein stability, degradation signals, functional regulation |

| Key Methodology | LC-MS/MS with label-free or isobaric tagging (TMT, iTRAQ) | Ubiquitin enrichment (antibodies, UBD domains) + LC-MS/MS |

| Sample Complexity | Total proteome | Ubiquitin-modified subproteome |

| Data Interpretation | Differential expression analysis | Ubiquitination site mapping, pathway activity inference |

| Functional Insight | Indirect | Direct assessment of regulatory mechanisms |

| Biomarker Potential | Expression-based biomarkers | Function-based biomarkers reflecting pathway activity |

Table 2: Capability Assessment for Cancer Biomarker Discovery

| Capability | Conventional Proteomics | Ubiquitinomics |

|---|---|---|

| Detection of Dysregulated Pathways | Moderate | High |

| Identification of Drug Targets | Limited to abundance changes | High (identifies stabilized/degraded targets) |

| Prognostic Value | Moderate (based on expression) | High (reflects functional state) |

| Therapeutic Monitoring | Expression changes | Direct degradation monitoring |

| Technical Complexity | Moderate | High (requires specialized enrichment) |

| Functional Context | Low | High |

Experimental Evidence: Functional Analysis Reveals What Expression Cannot

Case Study: Mutation Impacts on Protein vs. mRNA Expression

A comprehensive analysis of mutation impacts across six cancer types revealed striking disparities between mRNA and protein expression, highlighting the necessity of functional protein-level analysis [19].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Cohort: 953 cancer cases across breast cancer (BRCA), colorectal cancer (CRC), clear cell renal cell carcinoma (CCRCC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), ovarian cancer (OV), and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC)

- Multi-Omic Profiling: Paired DNA sequencing, RNA sequencing, and global proteomic profiling via mass spectrometry

- Statistical Analysis:

- Multiple regression adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, and batch effects

- Identification of somatic expression quantitative trait loci (seQTLs) and somatic protein QTLs (spQTLs)

- False discovery rate (FDR) control at < 0.05

- Validation: Cross-referencing with massively parallel assays of variant effects (MAVE) for TP53 mutations

Key Findings:

- Only 47.2% of somatic mutations affecting mRNA expression (seQTLs) showed concordant effects on protein expression

- Truncating mutations in genes like NF1 and ARID1A in UCEC showed disproportionate impact on protein abundance not explained by transcriptomics

- TP53 missense mutations in multiple cancer types significantly increased protein expression without corresponding mRNA changes

- Protein-specific QTLs (spsQTLs) identified mutations affecting protein stability, degradation, or translation efficiency

Case Study: Proteotranscriptomic Integration in Breast Cancer

An integrated proteotranscriptomic analysis of breast cancer demonstrated that increased protein-mRNA concordance itself associates with aggressive disease and poor survival outcomes [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: 65 breast tumors and 53 adjacent non-cancerous tissues

- Protein Extraction: Tissue pulverization under liquid nitrogen, protein digestion with trypsin

- LC-MS Analysis: Untargeted approach with 17 fractions per sample, analyzed via LTQ FT MS

- Data Processing:

- SEQUEST HT algorithm against UniProt Homo sapiens database

- Protein-level FDR cutoff of 5%

- DESeq2 for differential expression analysis

- rlog normalization for protein-mRNA correlation assessment

Key Findings:

- Proteome analysis revealed activation of infection-related pathways in basal-like tumors not detected by transcriptomics

- Global increase in protein-mRNA concordance associated with aggressive subtypes (basal-like/triple-negative)

- Highly correlated protein-gene pairs enriched in protein processing and metabolic pathways

- Increased protein-mRNA concordance predicted decreased patient survival

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Ubiquitinomics Workflow for Functional Assessment

Functional Impact of Mutations on Protein Regulation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitinomics and Proteomics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin (Protease) | Protein digestion into peptides for MS analysis | Standard sample preparation in both proteomics and ubiquitinomics [20] [18] |

| TMT (Tandem Mass Tag) Labels | Multiplexed isobaric labeling for quantitative comparison | Comparing protein expression across multiple samples simultaneously [18] |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides | Isolation of ubiquitinated proteins prior to LC-MS/MS analysis |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs) | Alternative enrichment method for ubiquitinated proteins | Selective capture of specific ubiquitin chain types |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | High-resolution separation and detection of peptides | Core analytical platform for both proteomics and ubiquitinomics [19] [20] |

| Protein Extraction Buffers | Cell lysis and protein solubilization | Initial sample preparation with protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors |

| Database Search Algorithms | Peptide identification from mass spectra | SEQUEST, MaxQuant for identifying proteins and ubiquitination sites [20] |

The evidence compellingly demonstrates that protein function provides more clinically relevant information than expression levels alone in cancer research. Ubiquitinomics enables researchers to move beyond static protein inventories to dynamic assessments of protein regulation, stability, and activity that more accurately reflect the functional state of tumors. While conventional proteomics remains valuable for initial discovery phases, the integration of ubiquitinomics and other functional proteomics approaches provides a more comprehensive understanding of tumor biology that can accelerate biomarker development and therapeutic discovery. The future of cancer proteomics lies in combining quantitative and functional analyses to create multidimensional maps of tumor proteomes that reflect both abundance and activity states.

Protein ubiquitination, a fundamental post-translational modification, has emerged as a central regulator of oncogenesis and tumor suppression. This reversible process involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, subsequently determining their stability, localization, and function [21]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a sophisticated regulatory network that extends far beyond protein degradation, encompassing critical roles in signal transduction, DNA damage response, and cell cycle progression [21]. When dysregulated, ubiquitination pathways contribute significantly to the acquisition of canonical cancer hallmarks, including sustained proliferation, evasion of growth suppressors, and resistance to cell death [22].

The emerging field of ubiquitinomics—the comprehensive study of ubiquitinated proteins and their modifications—provides unique insights into cancer mechanisms that often remain invisible to conventional proteomics. While traditional proteomics quantifies protein abundance, ubiquitinomics reveals the dynamic post-translational landscape that regulates protein activity, localization, and turnover within cancer cells [23]. This distinction is particularly relevant for biomarker discovery, as ubiquitination changes often precede and trigger alterations in protein abundance, offering potentially earlier detection windows and more mechanistically informative biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and therapeutic development [23] [7].

Ubiquitination Mechanisms and Regulatory Networks

The Ubiquitination Machinery

The ubiquitination cascade involves a sequential enzymatic process mediated by three key enzyme classes:

- E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes: Initiate ubiquitination by activating ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner

- E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes: Receive and transfer activated ubiquitin

- E3 ubiquitin ligases: Confer substrate specificity by recognizing target proteins and facilitating ubiquitin transfer [21] [24]

E3 ubiquitin ligases represent the most diverse and specialized component of this system, with approximately 600 members in humans that determine substrate recognition and biological specificity [24]. The complexity of ubiquitin signaling is further enhanced by the ability of ubiquitin itself to form polymer chains through different lysine residues (e.g., K48, K63), with K48-linked chains typically targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation and K63-linked chains often regulating signal transduction and DNA repair [25].

Visualization of Ubiquitination Networks

Table 1: Key Experimental Methods for Studying Ubiquitination in Cancer

| Method | Application | Key Insights | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination-Induced Fluorescence Complementation (UiFC) | Visualizing K48 ubiquitination dynamics in live cells | Revealed rapid accumulation of K48 ubiquitin at nascent presynaptic terminals; applicable to studying protein clustering in cancer | [25] |

| Anti-K-ε-GG antibody enrichment + LC-MS/MS | System-wide identification of ubiquitination sites | Identified 400 differentially ubiquitinated proteins with 654 sites in lung squamous cell carcinoma | [23] |

| Immunohistochemistry + Tissue microarrays | Validation of ubiquitination biomarkers in clinical specimens | Confirmed increased vimentin and MRP1 in LSCC tissues correlated with decreased patient survival | [23] [7] |

| Network analysis of E3-substrate relationships | Mapping ubiquitination regulatory networks | Constructed comprehensive maps of 41,392 ubiquitination sites from 12,786 proteins; revealed novel E3-substrate relationships | [24] |

Figure 1: Ubiquitination Cascade and Functional Outcomes. The enzymatic cascade of E1-E2-E3 enzymes mediates ubiquitin transfer to substrate proteins. Different polyubiquitin chain linkages determine functional fates, primarily proteasomal degradation (K48-linked) or signaling activation (K63-linked).

Ubiquitination in Cancer Hallmarks: Degradation Networks

Regulation of Tumor Suppressors by Ubiquitin-Mediated Degradation

The ubiquitin-proteasome system exerts precise control over key tumor suppressor proteins, with their aberrant degradation representing a common oncogenic mechanism across cancer types:

p53 Ubiquitination by MDM2 The p53 tumor suppressor serves as a paradigm for ubiquitin-mediated regulation in cancer. Under normal conditions, the E3 ligase MDM2 maintains p53 at low levels by facilitating its polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation [21]. This regulatory loop ensures that p53 activity is appropriately constrained in healthy cells. However, in many cancers, MDM2 gene amplification or overexpression leads to hyperactivation of this degradation pathway, resulting in excessive p53 destruction even in the presence of DNA damage [21]. This mechanism allows cancer cells to bypass critical cell cycle checkpoints and apoptosis, contributing significantly to uncontrolled proliferation and genomic instability. The clinical relevance of this pathway is underscored by the development of therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting MDM2-p53 interactions to reactivate p53 function in tumors [21].

Additional Tumor Suppressor Networks Beyond p53, numerous other tumor suppressors fall under ubiquitin-mediated control:

- RB (Retinoblastoma protein): Regulates G1 to S phase transition and is inactivated in many cancers through phosphorylation-induced ubiquitination and degradation [21]

- APC (Adenomatous polyposis coli): Frequently inactivated in colon cancer through mutations that disrupt its ubiquitin-mediated degradation function [21]

- PTEN: A critical tumor suppressor whose ubiquitination and degradation are linked to prostate cancer and glioblastoma development [21]

Oncoprotein Stabilization Through Dysregulated Ubiquitination

Equally important in cancer pathogenesis is the stabilization of oncoproteins resulting from disrupted ubiquitination:

c-Myc Stabilization The c-Myc transcription factor, a potent driver of cell proliferation, is normally maintained at appropriate levels through ubiquitin-mediated degradation orchestrated by E3 ligases such as FBW7 [21]. In cancer, mutations in FBW7 or deregulation of other ubiquitin ligases lead to c-Myc stabilization and overexpression, driving unchecked cell growth and survival in various leukemias, lymphomas, and solid tumors [21].

Ras Signaling Pathway The Ras family of small GTPases, including frequently mutated KRas, is regulated by ubiquitination through E3 ligases such as Cbl, which promotes Ras ubiquitination and degradation [21]. In cancer, mutations that disrupt these regulatory mechanisms lead to constitutive Ras signaling activation, fostering tumor growth, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [21].

Table 2: Key Ubiquitination Regulatory Nodes in Cancer Hallmarks

| Target Protein | Role in Cancer | Regulating E3 Ligase | Effect of Dysregulation | Cancer Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53 | Tumor suppressor | MDM2 | Excessive degradation enables uncontrolled proliferation | Breast, lung, colorectal cancers |

| c-Myc | Oncoprotein | FBW7 | Stabilization drives proliferation | Leukemias, lymphomas, solid tumors |

| Ras | Oncoprotein | Cbl | Stabilization promotes signaling | Pancreatic, colorectal, lung cancers |

| p27 | CDK inhibitor | SKP2 | Degradation allows cell cycle progression | Prostate, gastric cancers |

| Vimentin | Metastasis marker | TRIM2 (predicted) | Decreased ubiquitination increases stability | Lung squamous cell carcinoma |

Ubiquitination in Cancer Hallmarks: Signaling Networks

Cell Cycle Regulation Through Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination serves as a critical timer for cell cycle progression, controlling the stability of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and their inhibitors:

Cyclin Degradation Cyclins activate CDKs to drive cell cycle progression, with their periodic degradation essential for phase transitions. For example, cyclin E degradation by the APC/C E3 ligase complex prevents premature S-phase entry [21]. In cancers, dysregulation of this ubiquitin-mediated degradation results in cyclin overexpression or stabilization, driving continuous cell cycle progression independent of proper signals [21]. Overactivation of cyclins D and E is commonly observed in breast, lung, and colorectal cancers.

CDK Inhibitor Regulation CDK inhibitors including p21 and p27 normally function as cell cycle brakes by inhibiting CDK activity. Ubiquitination mediated by SCF complexes targets these inhibitors for degradation, allowing cell cycle progression [21]. In cancer, overactive ubiquitination leads to excessive degradation of CDK inhibitors, removing critical restraints on cell division [21].

DNA Damage Response and Ubiquitination

The DNA damage response (DDR) relies heavily on ubiquitin signaling to determine cell fate decisions between repair and apoptosis:

BRCA1 Regulation The BRCA1 tumor suppressor, crucial for DNA repair, is regulated by ubiquitination. Mutations affecting its ubiquitination pathway impair DNA repair function, increasing susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancers [21].

p53 in DNA Damage Ubiquitination of p53 following DNA damage helps dictate whether cells undergo repair or apoptosis, highlighting the intersection between ubiquitination, tumor suppressor regulation, and genome integrity maintenance [21].

Figure 2: Ubiquitination-Mediated Regulation of Cancer Hallmarks. The ubiquitin-proteasome system contributes to multiple cancer hallmarks through distinct mechanistic pathways involving both degradation and non-degradative signaling functions.

Ubiquitinomics Versus Proteomics in Cancer Biomarker Discovery

Methodological Comparison

The distinction between ubiquitinomics and conventional proteomics approaches has significant implications for cancer biomarker discovery:

Ubiquitinomics Workflow Ubiquitinomics specifically targets the ubiquitinated portion of the proteome using anti-K-ε-GG antibodies to enrich ubiquitinated peptides prior to LC-MS/MS analysis [23]. This approach allows identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites, providing direct insight into post-translational regulatory events rather than simply measuring protein abundance [23]. For example, in lung squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC), this method identified 400 differentially ubiquitinated proteins with 654 ubiquitination sites, revealing metabolic reprogramming and altered cell adhesion networks that might remain undetected by standard proteomics [23].

Traditional Proteomics Approach Conventional proteomics analyzes total protein content using techniques such as liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and protein microarrays to identify differential protein expression across biological states [1]. While valuable for cataloging protein abundance changes, this approach may miss critical regulatory events occurring at the post-translational level.

Table 3: Comparison of Ubiquitinomics and Proteomics Approaches in Cancer Research

| Parameter | Ubiquitinomics | Traditional Proteomics |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Focus | Ubiquitination sites and modifications | Protein identification and abundance |

| Key Enrichment Step | Anti-K-ε-GG antibody enrichment | Various fractionation methods (e.g., SDS-PAGE) |

| Biological Insight | Regulatory mechanisms, protein turnover | Protein expression changes |

| Cancer Biomarker Potential | Functional regulation, early detection | Abundance alterations, classification |

| Technical Challenge | Low-abundance modification detection | Dynamic range limitations |

| Representative Findings | Decreased vimentin ubiquitination in LSCC [23] | Differential protein panels for multiclass cancer [7] |

Clinical Applications and Biomarker Potential

Ubiquitination-related proteins show significant promise as cancer biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring:

E3 Ligases as Biomarkers

- MDM2: Overexpression associated with poor prognosis in breast, lung, and colorectal cancers [21]

- SKP2: High expression linked to increased invasiveness and poor prognosis in prostate and gastric cancers [21]

Deubiquitinases (DUBs) as Biomarkers

- USP7: Overexpression implicated in progression of various cancers through stabilization of both MDM2 and p53 [21]

- USP9X: Associated with chemotherapy resistance through stabilization of anti-apoptotic protein MCL-1 [21]

Ubiquitination Substrates as Biomarkers

- p53 ubiquitination status: Correlates with cancer invasiveness and treatment response [21]

- Vimentin ubiquitination: Decreased ubiquitination associated with increased protein stability in LSCC [23]

The clinical relevance of ubiquitination biomarkers is further supported by integrative multi-omics analyses. For example, combining ubiquitinomics data with transcriptomics from TCGA database revealed that highly expressed VIM and IGF1R mRNAs correlated with poorer prognosis in LSCC, while highly expressed ABCC1 mRNA associated with better prognosis [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifics | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibodies | Enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for MS | Commercial monoclonal antibodies | Ubiquitinomics profiling [23] |

| UiFC Plasmids | Visualizing K48 ubiquitination in live cells | pcDNA3-UiFC-C and pcDNA3-UiFC-N | Live-cell ubiquitination dynamics [25] |

| E3 Ligase Libraries | Screening for substrate recognition | Collections of 494+ non-redundant E3s | Ubiquitination network mapping [24] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Block degradation to study ubiquitination | Bortezomib, carfilzomib | Substrate identification [21] [23] |

| Ubiquitin Binding Domains | Detection and purification of ubiquitinated proteins | UIM, UBA, BUZ domains | Affinity capture for MS analysis [21] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Profiling deubiquitinating enzyme activities | Ubiquitin-based chemical probes | DUB inhibitor development [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Ubiquitination Studies

Ubiquitinomics Profiling from Tissue Samples

The following protocol has been successfully applied to identify differentially ubiquitinated proteins in lung squamous cell carcinoma:

Tissue Processing and Protein Extraction

- Mix tissue samples (150mg per patient, typically 5 patients per group) to create pooled samples

- Homogenize in urea lysis buffer (7M urea, 2M thiourea, 100mM DTT, 1mM PMSF)

- Sonicate (80W, 10s pulses with 15s intervals, 10 cycles)

- Centrifuge at 15,000×g for 20 minutes at 4°C

- Collect supernatant and quantify protein using Bradford method [23]

Trypsin Digestion and Peptide Preparation

- Reduce samples with DTT (10mM final, 37°C for 1.5 hours)

- Alkylate with iodoacetamide (50mM final, room temperature for 30 minutes in darkness)

- Digest with trypsin (1:50 trypsin:protein ratio) at 37°C for 15-18 hours

- Acidify with trifluoroacetic acid (0.1% final, pH ≤3)

- Desalt using C18 cartridges [23]

Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment and LC-MS/MS Analysis

- Enrich ubiquitinated peptides using anti-K-ε-GG antibody-based capture

- Perform liquid chromatography using C18 columns (75μm, 12cm)

- Elute with linear gradient from H2O/CH3CN (95:5) to H2O/CH3CN (70:30) over 70 minutes

- Analyze using LTQ FT MS with full MS scan (400-1600 m/z) followed by data-dependent MS/MS of five most intense ions [23]

Data Analysis

- Search data against Swiss-Prot database using SEQUEST algorithm

- Apply PeptideProphet scoring (threshold ≥0.7) for identification confidence

- Identify differentially ubiquitinated proteins using spectral counting or label-free quantification [23]

Ubiquitination-Induced Fluorescence Complementation (UiFC)

The UiFC method enables visualization of K48-linked ubiquitination dynamics in live cells:

Principle UiFC utilizes split Venus fluorescent protein fragments fused to ubiquitin-interacting motifs that specifically recognize K48-linked ubiquitin chains. When in proximity due to binding to the same ubiquitin chain, the fragments reconstitute a functional fluorescent protein, producing a detectable signal [25].

Neuronal Culture and Transfection

- Prepare primary hippocampal neurons from E17 rat embryos

- Maintain in neurobasal medium with B27 supplement

- Transfect at days in vitro (DIV) 7/8 using appropriate transfection reagents

- Employ plasmids: pcDNA3-UiFC-C (UiFC-C) and pcDNA3-UiFC-N (UiFC-N) [25]

Imaging and Analysis

- Image live cells using standard fluorescence microscopy

- Quantify UiFC signal accumulation at regions of interest

- Perform colocalization analysis with organelle or protein markers

- For presynaptic formation studies, utilize microfluidic devices to isolate axons [25]

Validation

- Verify specificity using K48-specific ubiquitin antibodies

- Confirm dependency on E1-mediated ubiquitination using E1 inhibitors [25]

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The central role of ubiquitination in cancer pathogenesis has motivated developing therapeutic strategies targeting this system:

Targeting Ubiquitination Enzymes

E3 Ligase Inhibitors Several E3 ligases represent promising drug targets due to their substrate specificity and frequent dysregulation in cancer. MDM2 inhibitors aim to reactivate p53 by disrupting MDM2-p53 interactions, with multiple candidates in clinical development [21]. Similarly, inhibitors targeting other cancer-relevant E3 ligases such as SCF complexes are under investigation [21].

DUB Inhibitors Deubiquitinating enzymes that stabilize oncoproteins represent another therapeutic avenue. USP7 and USP9X inhibitors could potentially counteract their oncogenic effects by promoting degradation of stabilized oncoproteins like MCL-1 [21].

Proteasome Inhibitors and Beyond

Proteasome inhibitors including bortezomib and carfilzomib have established clinical efficacy in hematological malignancies by inducing proteotoxic stress in cancer cells [21] [23]. Next-generation approaches include:

Molecular Glues These small molecules induce proximity between E3 ubiquitin ligases and target proteins, enabling degradation of previously "undruggable" targets [26]. This approach is experiencing rapid growth in preclinical research and early clinical development [26].

Radiopharmaceuticals Combining ubiquitination-targeting vectors with radioactive isotopes represents an emerging strategy for precise cancer therapy. Candidates such as FPI-2265 (in phase 2/3 trials for prostate cancer) and Radio-DARPins (entering clinical trials in 2025) leverage specific targeting for localized radiation delivery [26].

The expanding toolkit for modulating ubiquitination pathways, combined with increasingly sophisticated ubiquitinomics approaches for patient stratification and treatment monitoring, promises to advance personalized cancer therapy based on the ubiquitination signatures of individual tumors.

The discovery and clinical implementation of robust cancer biomarkers represent a critical pathway for advancing precision oncology. Biomarkers, defined as measurable indicators of biological processes or pathogenic responses, are indispensable for early cancer detection, accurate prognosis, and predicting treatment responses [27] [28]. Despite tremendous technological advancements and the discovery of thousands of candidate biomarkers, a striking discrepancy exists between research output and clinical adoption, with an estimated success rate of only 0.1% for biomarker translation into routine clinical practice [27] [29]. This translation gap represents a significant clinical imperative that must be addressed to fulfill the promise of personalized cancer medicine.

The challenges in biomarker translation are multifaceted, stemming from issues in study design, analytical validation, clinical utility assessment, and regulatory hurdles [27] [29]. This review examines the biomarker translation pipeline through the comparative lens of proteomics—the large-scale study of proteins and their functions—and the more specialized field of ubiquitinomics, which focuses on the system-wide analysis of protein ubiquitination. By comparing these complementary approaches, we aim to provide researchers with a strategic framework for navigating the complex journey from biomarker discovery to clinical application.

The Biomarker Development Pipeline: From Discovery to Clinical Implementation

Phases of Biomarker Development

The path from initial discovery to clinically implemented biomarkers follows a structured pipeline with distinct phases [29]:

- Preclinical Exploratory Phase: Identification of promising leads through unbiased or targeted discovery approaches

- Clinical Assay Development and Validation: Establishment of robust, clinically applicable assays

- Retrospective Longitudinal Studies: Assessment of biomarker performance using archived specimens

- Prospective Screening Studies: Evaluation in intended-use population with predefined endpoints

- Cancer Control Phase: Implementation in clinical practice and assessment of impact on population health

This phased approach ensures rigorous evaluation at each step, yet many biomarkers fail to progress beyond the early stages due to issues with analytical validity, clinical utility, or practical implementation [27] [29]. The use of "samples of convenience" collected without specific biomarker intentions, inadequate statistical power, and poorly defined clinical endpoints contribute significantly to this attrition rate [27].

Analytical and Clinical Considerations

For successful translation, biomarkers must demonstrate both analytical and clinical validity [29]. Analytical validity refers to the assay's accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and specificity in measuring the biomarker, while clinical validity establishes that the biomarker reliably predicts the clinical phenotype of interest [30] [29]. Key statistical metrics for evaluating biomarker performance include sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves with area under the curve (AUC) analysis [30].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Biomarker Evaluation

| Metric | Definition | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Proportion of true positives correctly identified | Ability to detect disease when present |

| Specificity | Proportion of true negatives correctly identified | Ability to correctly exclude disease |

| Positive Predictive Value | Proportion of test positives with the disease | Probability of disease given positive test |

| Negative Predictive Value | Proportion of test negatives without the disease | Probability of no disease given negative test |

| ROC-AUC | Overall discrimination ability | Diagnostic accuracy across all thresholds |

The intended use of a biomarker must be defined early in development, as this determines the required evidence and regulatory pathway [30]. Biomarkers can serve as diagnostic tools for detecting cancer, prognostic indicators of disease course, or predictive markers of treatment response [27] [28] [31].

Proteomics in Cancer Biomarker Discovery

Technological Platforms and Workflows

Proteomics has emerged as a powerful tool for cancer biomarker discovery, providing direct insight into the functional molecules that drive oncogenic processes [1] [18]. Mass spectrometry (MS)-based technologies form the cornerstone of modern proteomics, enabling large-scale protein identification and quantification [18]. The general workflow involves protein extraction from clinical samples (tissues, blood, or other biofluids), protease digestion (typically with trypsin), peptide fractionation to reduce complexity, and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis [7] [18].

Two primary quantitative approaches dominate the field: label-based methods using isobaric tags (TMT, iTRAQ) or stable isotope labeling (SILAC), and label-free techniques based on spectral counting or signal intensity [18]. Label-based approaches offer higher accuracy but increased cost and complexity, while label-free methods provide greater scalability for large sample cohorts [18].

Figure 1: Proteomics Workflow for Biomarker Discovery

Applications in Cancer Research

Proteomics has been successfully applied across multiple cancer types to identify biomarkers for early detection, classification, and therapeutic monitoring. In gastrointestinal cancers, proteomic analysis of conditioned media from primary tumor tissues identified 12 differentially expressed proteins—including vimentin (VIM), pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), and various keratins—that could distinguish between colon, kidney, liver, and brain tumors [7]. Similarly, in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), isobaric labeling TMT proteomics revealed that phosphorylation of ALDOA promotes glycolysis and proliferation in CTNNB1-mutated HCC cells [18].

The strength of proteomics lies in its ability to provide direct measurement of functional effector molecules, capturing post-translational modifications, protein-protein interactions, and pathway activities that cannot be deduced from genomic or transcriptomic analyses alone [1] [18]. This provides a more comprehensive view of the oncogenic processes driving tumor progression.

Ubiquitinomics: A Specialized Frontier in Cancer Proteomics

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in Cancer

Ubiquitinomics represents a specialized subset of proteomics focused on system-wide analysis of protein ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification that regulates protein degradation, signaling, and localization [18]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) plays a fundamental role in controlling cellular processes frequently dysregulated in cancer, including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and DNA repair [18]. As such, comprehensive profiling of ubiquitin signatures offers unique opportunities for biomarker discovery and therapeutic targeting.

Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, forming complex chains that determine the protein's fate. The specificity of ubiquitination is controlled by E3 ubiquitin ligases, while deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) remove ubiquitin modifications, creating a dynamic regulatory system [18]. Cancer cells often exploit this system to destabilize tumor suppressors or stabilize oncoproteins, making ubiquitinomics particularly relevant for understanding cancer mechanisms.

Methodological Approaches in Ubiquitinomics

Ubiquitinomics employs specialized enrichment strategies to isolate and identify ubiquitinated peptides from complex protein mixtures. The most common approach utilizes antibodies specific for di-glycine remnants left on tryptic peptides after ubiquitination, followed by LC-MS/MS analysis [18]. Advanced methods have also been developed to distinguish between different ubiquitin chain linkages, which can have distinct functional consequences for the modified proteins.

Figure 2: Ubiquitinomics Workflow for Biomarker Discovery

Quantitative ubiquitinomics can reveal dynamic changes in the ubiquitin landscape in response to therapeutic interventions or during disease progression. For example, profiling ubiquitination changes in response to proteasome inhibitors has identified novel regulators of therapy resistance in multiple cancer types [18]. These approaches provide unique insights into protein turnover dynamics and regulatory mechanisms that are invisible to conventional proteomic methods.

Comparative Analysis: Ubiquitinomics vs. Proteomics for Biomarker Translation

Technical and Analytical Considerations

The translation potential of biomarkers discovered through proteomic versus ubiquitinomic approaches differs significantly in terms of technical requirements, clinical applicability, and validation strategies. The table below provides a direct comparison of these complementary approaches:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Proteomics vs. Ubiquitinomics for Biomarker Development

| Parameter | Proteomics | Ubiquitinomics |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Focus | Protein expression, abundance, and modifications | Specific ubiquitination events and patterns |

| Biological Insight | Steady-state protein levels | Protein turnover, degradation dynamics, signaling regulation |

| Technical Complexity | Moderate to high | High (requires specialized enrichment) |

| Clinical Applicability | Broad (diagnosis, prognosis, monitoring) | Targeted (therapy response, resistance mechanisms) |

| Assay Translation | Established pathways (ELISA, immunoassays) | Emerging technologies, primarily MS-based |

| Regulatory Precedence | Multiple FDA-approved protein biomarkers | Limited clinical implementation to date |

| Strength | Comprehensive molecular profiling | Functional insight into regulatory mechanisms |

| Sample Requirements | Standard collection protocols | Critical preservation of modification states |

Clinical Translation Potential

Proteomics offers a broader pathway for clinical translation, with established technologies like immunoassays (ELISA, IHC) that can be readily implemented in clinical laboratories [29]. Several protein biomarkers have successfully navigated the FDA approval process, including the OVA1 test for ovarian cancer, which measures five protein biomarkers in blood [32]. The transition from discovery platforms (e.g., mass spectrometry) to clinical assays often requires method adaptation, as demonstrated by OVA1, which was initially developed on SELDI technology but ultimately implemented using immunoassays to achieve required precision levels [29].

In contrast, ubiquitinomics faces greater translational challenges due to the technical complexity of preserving and measuring ubiquitination states in clinical specimens. The dynamic nature of ubiquitin modifications and the need for specialized analytical platforms currently limit their implementation in routine clinical practice. However, ubiquitinomics provides unparalleled insight into drug mechanism of action and resistance pathways, making it particularly valuable for pharmacodynamic biomarker development and therapy personalization [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful biomarker translation requires careful selection of research reagents and platforms that ensure analytical rigor and reproducibility. The following table outlines essential tools for proteomics and ubiquitinomics research:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Discovery

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometers (LTQ FTMS, Q-Exactive) | Protein/peptide identification and quantification | High-resolution instruments essential for complex samples [7] |

| Chromatography Systems (nanoLC, HPLC) | Peptide separation prior to MS analysis | Critical for reducing sample complexity [7] [18] |

| Trypsin | Proteolytic digestion of proteins | Standard enzyme for bottom-up proteomics [7] [18] |

| Isobaric Tags (TMT, iTRAQ) | Multiplexed quantitative proteomics | Enable simultaneous analysis of multiple samples [18] |

| Anti-diGly Antibodies | Enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides | Essential for ubiquitinomics studies [18] |

| Protein Arrays | High-throughput protein profiling | Useful for validation studies [31] |

| Database Search Tools (SEQUEST, MaxQuant) | Protein identification from MS data | Require curated databases for accurate identification [7] |

| Statistical Analysis Packages | Biomarker candidate selection | Must control for multiple comparisons [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Discovery and Validation

Tissue-Derived Proteome Profiling Protocol

The following protocol, adapted from cancer biomarker studies [7], outlines the standard workflow for tissue-based biomarker discovery:

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Obtain tissue specimens with appropriate ethical approval and histological confirmation

- Rinse tissue pieces with PBS and place in defined medium (DMEM/F12 with growth factor cocktail) overnight at 4°C

- Centrifuge at 2,000 rpm for 10 minutes and desalt conditioned media using PD-10 columns

Protein Extraction and Digestion:

- Solubilize protein pellets in 7M urea, 2M thiourea, and 25mM ammonium bicarbonate

- Desalt using spin columns and quantify protein concentration with BCA assay

- Reduce with 5mM DTT at 50°C for 30 minutes, then alkylate with 15mM iodoacetamide

- Digest with trypsin (1:50 ratio) at 37°C overnight

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Load trypsin-digested samples onto C18 analytical columns (75μm, 12cm)

- Elute peptides using linear gradient from 5% to 30% acetonitrile over 70 minutes

- Acquire full MS scan (400-1600 m/z) followed by data-dependent MS/MS of the five most intense ions

Data Processing and Biomarker Identification:

- Search MS/MS data against Swiss-Prot database using SEQUEST algorithm

- Apply PeptideProphet filter (score ≥0.7) for confident identifications

- Perform quantitative analysis using spectral counting or label-free quantification

Biomarker Validation Protocol

Transitioning from discovery to validation requires orthogonal methods to confirm biomarker candidates [29]:

Analytical Validation:

- Assess precision (within-run, between-run), trueness, limit of detection, and linearity

- Evaluate analyte stability under storage conditions and freeze-thaw cycles

- Determine reference intervals in relevant populations

Clinical Validation:

- Perform retrospective analysis using predefined endpoints in independent sample sets

- Assess diagnostic sensitivity and specificity using ROC curve analysis

- For predictive biomarkers, test treatment-biomarker interaction in randomized trial data [30]

Assay Implementation:

- Transition from discovery platform (MS) to clinical applicable format (immunoassay)

- Establish quality control procedures and reference materials

- Document analytical performance following regulatory guidelines (FDA, CLIA) [29]

The translation gap in cancer biomarkers represents both a challenge and opportunity for the oncology research community. Addressing this gap requires a multifaceted strategy that incorporates rigorous study design, robust analytical validation, and clear clinical utility from the earliest stages of biomarker development [27] [29]. While proteomics offers a broader path to clinical implementation with established translation pathways, ubiquitinomics provides unique functional insights into cancer mechanisms, particularly for understanding drug responses and resistance.

Future progress will likely depend on integrated multi-omics approaches that combine proteomics, ubiquitinomics, genomics, and metabolomics to create comprehensive molecular portraits of cancer biology [31] [32]. The emergence of artificial intelligence and machine learning tools for analyzing complex biomarker data offers promising avenues for identifying subtle patterns with clinical significance [32]. Furthermore, the development of novel technologies such as liquid biopsies for circulating tumor DNA and proteins, nanotechnology-based detection platforms, and high-throughput multiplexed assays will expand the possibilities for non-invasive cancer detection and monitoring [32].

By understanding the relative strengths and translational considerations of proteomics versus ubiquitinomics, researchers can make strategic decisions in biomarker development, ultimately accelerating the delivery of clinically impactful tools that improve cancer diagnosis, treatment selection, and patient outcomes. The clinical imperative is clear: only through deliberate, collaborative, and rigorous approaches to biomarker validation will we successfully bridge the translation gap and realize the full potential of precision oncology.

Advanced Technological Platforms: Mapping the Cancer Ubiquitinome and Proteome

In the pursuit of cancer biomarkers, proteomics has become an indispensable tool for characterizing protein expression, post-translational modifications (PTMs), and signaling pathway alterations in tumor biology. Mass spectrometry (MS)-based workflows now enable deep, quantitative profiling of complex proteomes from clinical specimens. Within this landscape, Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA), Tandem Mass Tag (TMT), and Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation (iTRAQ) have emerged as three principal methodologies for global proteomic analysis [33] [34]. The selection of an appropriate workflow profoundly influences the depth of proteome coverage, quantitative accuracy, and practical feasibility of large-scale studies, particularly in the context of ubiquitinomics for biomarker discovery [35]. Ubiquitination, a critical PTM, regulates diverse cellular processes including protein degradation, and its dysregulation is extensively associated with carcinogenesis [35] [34]. This guide provides an objective comparison of DIA, TMT, and iTRAQ workflows, framing their performance within the specific challenges of cancer proteomics and ubiquitinomics.

TMT (Tandem Mass Tag) and iTRAQ (Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation)

TMT and iTRAQ are isobaric chemical labeling techniques that enable multiplexed relative quantification of proteins across multiple samples [36].

- Principle of Operation: Peptides from different samples are labeled with amine-reactive tags that have identical total mass (isobaric). The tags consist of a mass reporter group, a balance group, and a reactive group that covalently binds to peptide N-termini and lysine side chains [36]. Labeled peptides are pooled and analyzed simultaneously by LC-MS/MS. In MS2 spectra, fragmentation of the tags generates low-mass reporter ions whose intensities provide relative quantification of the peptide across samples [33] [36].

- Key Characteristics: TMT is available in 6-plex, 10-plex, and 16-plex configurations, while iTRAQ typically offers 4-plex or 8-plex kits [33] [36]. This multiplexing capacity allows direct comparison of multiple samples in a single MS run, reducing instrument time and technical variation [37].

DIA (Data-Independent Acquisition)

DIA is a label-free acquisition technique that provides comprehensive, reproducible profiling of complex proteomes [33] [38].

- Principle of Operation: Instead of selectively isolating top-intensity precursors as in traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA), DIA cycles through sequential, wide isolation windows (e.g., 25 m/z) covering a broad mass range (400-1200 m/z). All peptides within each window are fragmented simultaneously, producing highly complex MS2 spectra containing fragments from all co-eluting peptides [33] [38]. Peptide identification and quantification rely on extracting fragment ion chromatograms using project-specific spectral libraries [38].

- Key Characteristics: As a label-free method, DIA does not require chemical tagging, simplifying sample preparation and eliminating labeling efficiency concerns. Its sequential isolation of all ions ensures consistent data acquisition across samples, minimizing missing values [33].

The diagram below illustrates the core operational principles and workflow differences between these techniques.

Performance Comparison in Proteomic Studies

Independent comparative studies have systematically evaluated the performance of DIA and TMT workflows for quantitative proteomics. A multi-laboratory evaluation conducted by researchers from the Leibniz Institute on Aging and Biognosys provides key experimental insights [37].

Experimental Design and Comparative Data

In a benchmark study published in the Journal of Proteome Research, researchers compared TMT (MS3-based) and DIA workflows using 10 biological replicates of mouse cerebellum tissue spiked with UPS1 protein standard at five different concentrations [37]. This design enabled assessment of identification depth, quantitative precision, and accuracy under controlled conditions.

Key Findings: The TMT method identified 15-20% more proteins with somewhat better quantitative precision, while the DIA approach demonstrated superior quantitative accuracy [37]. Both methods quantified over 5,000 proteins with minimal missing values (<2%), confirming their robustness for comprehensive proteome analysis [37].

Comprehensive Technique Comparison

The table below synthesizes performance characteristics across multiple parameters based on published comparisons and technical specifications.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of DIA, TMT, and iTRAQ Workflows

| Parameter | DIA | TMT | iTRAQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Principle | Label-free, MS2 fragment intensity [33] | Isobaric labeling, MS2/MS3 reporter ions [33] [36] | Isobaric labeling, MS2 reporter ions [36] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Unlimited (sample number not limited by kit) [39] | Up to 16-18 samples (limited by kit) [33] [39] | 4-8 samples (limited by kit) [36] |

| Identification Coverage | High with full-scan coverage [33] | Relatively high [33] | Moderate [36] |