Validating Ubiquitination Sites: A Comprehensive Guide to Mutagenesis and Immunoblotting for Researchers

This article provides a detailed methodological guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating protein ubiquitination sites through the combined power of site-directed mutagenesis and immunoblotting.

Validating Ubiquitination Sites: A Comprehensive Guide to Mutagenesis and Immunoblotting for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a detailed methodological guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating protein ubiquitination sites through the combined power of site-directed mutagenesis and immunoblotting. Covering the entire workflow from foundational principles to advanced validation techniques, we explore how to confirm putative ubiquitination sites by mutating candidate lysine residues to arginine and detecting molecular weight shifts via immunoblotting. The content includes practical troubleshooting advice, optimization strategies for enhancing specificity, and comparative analysis with mass spectrometry and computational prediction methods. This resource aims to equip scientists with robust experimental frameworks for elucidating ubiquitination-mediated regulatory mechanisms in health and disease.

Ubiquitination Fundamentals: From Molecular Mechanisms to Functional Consequences

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is the primary pathway for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, representing a crucial regulatory mechanism that governs virtually all cellular processes, from cell cycle progression to DNA repair and immune responses [1] [2]. This system functions through a sophisticated enzymatic cascade that tags proteins for degradation with the small, highly conserved protein ubiquitin [3]. The specificity and precision of this system are conferred by its multi-enzyme architecture, involving E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases working in concert [1] [4]. Countering this process is a family of specialized proteases known as deubiquitinases (DUBs) that reverse ubiquitination by cleaving ubiquitin from substrate proteins, creating a dynamic equilibrium essential for cellular homeostasis [5] [6]. Dysregulation of UPS components is implicated in numerous pathologies, particularly cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, making this system an attractive target for therapeutic development [7] [2]. This review explores the enzymatic cascade, regulatory components, and experimental methodologies for studying ubiquitination, with particular focus on validation through mutagenesis and immunoblotting.

The Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

The Three-Step Enzymatic Reaction

Ubiquitination involves a sequential cascade of three enzyme families that ultimately conjugate ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins. The process begins with E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes, which initiate the pathway in an ATP-dependent manner. E1 enzymes catalyze the formation of a high-energy thioester bond between their active-site cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [1] [2]. Humans possess only two E1 enzymes, highlighting their fundamental role as entry points to the ubiquitination pathway [7] [2].

The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (also called ubiquitin-carrier enzymes) through a trans-thioesterification reaction, forming an E2~Ub thioester intermediate [1] [4]. The human genome encodes approximately 30-40 E2 enzymes, which begin to impart specificity to the system [3] [7].

The final step involves E3 ubiquitin ligases, which function as matchmakers that specifically recognize both the E2~Ub complex and the target substrate protein. E3 ligases facilitate the direct or indirect transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate protein, forming an isopeptide bond [1] [4]. With over 600 members in humans, E3 ligases provide the remarkable substrate specificity of the ubiquitination system [1] [7].

Table 1: Core Enzymes in the Ubiquitination Cascade

| Enzyme Class | Human Genes | Core Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | 2 [7] [2] | Ubiquitin activation via ATP hydrolysis | ATP-dependent, forms E1-Ub thioester |

| E2 (Conjugating) | ~30-40 [3] [7] | Ubiquitin carrier | Determines ubiquitin chain topology |

| E3 (Ligating) | ~600 [1] [7] | Substrate recognition | Provides specificity to UPS |

E3 Ligase Classifications and Mechanisms

E3 ubiquitin ligases are categorized into three major families based on their structural features and catalytic mechanisms. RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3 ligases represent the largest family, characterized by a RING finger domain that binds both the E2~Ub complex and the substrate. Rather than forming a covalent intermediate, RING E3s function as scaffolds that position the E2~Ub close to the substrate to enable direct ubiquitin transfer [1] [8]. A prominent subgroup includes the multi-subunit Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), which utilize cullin proteins as scaffolds to bring together substrate-recognition modules and RING components [1].

HECT (Homologous to E6AP C-terminus) E3 ligases employ a distinct catalytic mechanism involving a conserved HECT domain with an active-site cysteine residue. These enzymes form a transient thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [1]. The HECT family includes the well-characterized Nedd4 subfamily, which typically contains WW domains for substrate recognition and C2 domains for membrane localization [1].

RBR (RING-Between-RING) E3 ligases represent a hybrid class that combines features of both RING and HECT mechanisms. While they contain RING domains that bind E2~Ub complexes, they also feature a catalytic cysteine residue that forms a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before final transfer to substrates, similar to HECT E3s [1] [2]. PARKIN, mutations in which cause familial Parkinson's disease, is a notable RBR E3 ligase [2].

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

Deubiquitinases (DUBs): Reversal of Ubiquitination

DUB Classification and Functions

Deubiquitinases (DUBs) constitute a superfamily of proteases that counterbalance ubiquitination by cleaving ubiquitin from modified substrates. These enzymes perform several essential functions: they process inactive ubiquitin precursors to generate mature ubiquitin, remove ubiquitin chains from substrates to reverse their fate, and edit or disassemble unanchored ubiquitin chains for recycling [5] [6] [9]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, which are classified into two major classes based on their catalytic mechanisms [5] [6].

Cysteine protease DUBs represent the largest group and are further subdivided into four main families: Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs), Ovarian Tumor Proteases (OTUs), Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolases (UCHs), and Machado-Josephin Domain Proteases (MJDs) [6] [9]. These enzymes employ a catalytic triad or dyad containing a nucleophilic cysteine residue that attacks the isopeptide bond between ubiquitin and the substrate [6].

Metalloprotease DUBs belong to the JAMM/MPN+ family and utilize a coordinated zinc ion to activate a water molecule for nucleophilic attack on the isopeptide bond [6] [9]. Unlike cysteine proteases, JAMM/MPN+ DUBs do not form covalent intermediates during catalysis [6].

Table 2: Major Deubiquitinase (DUB) Families

| DUB Family | Catalytic Type | Human Members | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP | Cysteine protease | ~58 [9] | USP7, USP9X, USP28 |

| OTU | Cysteine protease | 14 [9] | OTUB1, A20 |

| UCH | Cysteine protease | 4 [9] | UCH-L1, UCH-L3, BAP1 |

| MJD | Cysteine protease | 5 [9] | Ataxin-3, Josephin-1 |

| JAMM/MPN+ | Zinc metalloprotease | 14 [9] | RPN11, BRCC36 |

Regulation of DUB Activity and Function

DUBs are subject to multiple layers of regulation to ensure precise spatiotemporal control of deubiquitination. Many DUBs feature modular architectures with regulatory domains that influence their catalytic activity, subcellular localization, and substrate specificity [6]. For instance, USP7 contains five C-terminal ubiquitin-like (UBL) domains that undergo intramolecular interactions to regulate its enzymatic activity [6]. Similarly, the tumor suppressor BAP1 forms a stable complex between its N-terminal catalytic domain and C-terminal domain, which is essential for cofactor-mediated activation [6].

DUBs are also regulated through obligate and facultative protein complexes that control their stability, activity, and substrate targeting. For example, the proteasomal DUB RPN11 (PSMD14) is only active when incorporated into the 26S proteasome, while UCHL5 (UCH37) requires binding to either the proteasome or the INO80 chromatin-remodeling complex for full activation [6].

Post-translational modifications represent another crucial regulatory mechanism for DUB function. Phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination can modulate DUB stability, catalytic activity, protein-protein interactions, and subcellular localization [6]. These multiple regulatory layers ensure that DUBs maintain ubiquitin homeostasis and execute precise substrate deubiquitination without promiscuous activity.

Experimental Validation of Ubiquitination

Methodologies for Detecting Protein Ubiquitination

The experimental validation of protein ubiquitination employs various methodologies, each with specific applications, advantages, and limitations. Traditional immunoblotting approaches remain widely used for initial detection and validation of ubiquitination. In this method, proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to membranes, which are then probed with ubiquitin-specific antibodies. A characteristic shift to higher molecular weights suggests ubiquitination, which can be further confirmed by mutating putative lysine residues to arginine to abolish ubiquitination sites [3].

Ubiquitin tagging-based approaches enable higher-throughput profiling of ubiquitinated substrates. These methods involve expressing epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, HA, or FLAG tags) in cells, followed by affinity purification under denaturing conditions to capture ubiquitinated proteins. After tryptic digestion, ubiquitination sites are identified by mass spectrometry through the detection of a 114.04 Da mass shift on modified lysine residues [3]. While this approach is relatively accessible and cost-effective, potential artifacts may arise because tagged ubiquitin may not completely mimic endogenous ubiquitin.

Ubiquitin antibody-based approaches allow enrichment of endogenously ubiquitinated proteins without genetic manipulation. Pan-specific ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) can enrich various ubiquitinated proteins, while linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., K48-, K63-specific) enable the study of specific chain types [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for clinical samples where genetic manipulation is infeasible, though antibody cost and potential non-specific binding represent limitations.

Ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD)-based approaches utilize natural ubiquitin receptors to enrich ubiquitinated proteins. Single UBDs typically exhibit low affinity, necessitating tandem-repeated UBDs for efficient purification [3]. This method provides a more physiological approach to studying endogenous ubiquitination.

Table 3: Methods for Ubiquitination Detection and Validation

| Method | Principle | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoblotting + Mutagenesis | Lysine mutation and antibody detection | Target validation | Accessible, specific | Low-throughput, candidate-based |

| Ubiquitin Tagging | Affinity purification of tagged ubiquitin conjugates | Ubiquitinome profiling | Relatively easy, low-cost | Potential artifacts from tagged Ub |

| Ub Antibody Enrichment | Immunoaffinity with ubiquitin antibodies | Endogenous ubiquitination | Works with clinical samples | Antibody cost, potential non-specificity |

| UBD-based Enrichment | Affinity purification with ubiquitin-binding domains | Physiological ubiquitination | Mimics natural recognition | May require tandem domains for affinity |

Validating Ubiquitination Sites by Mutagenesis and Immunoblotting

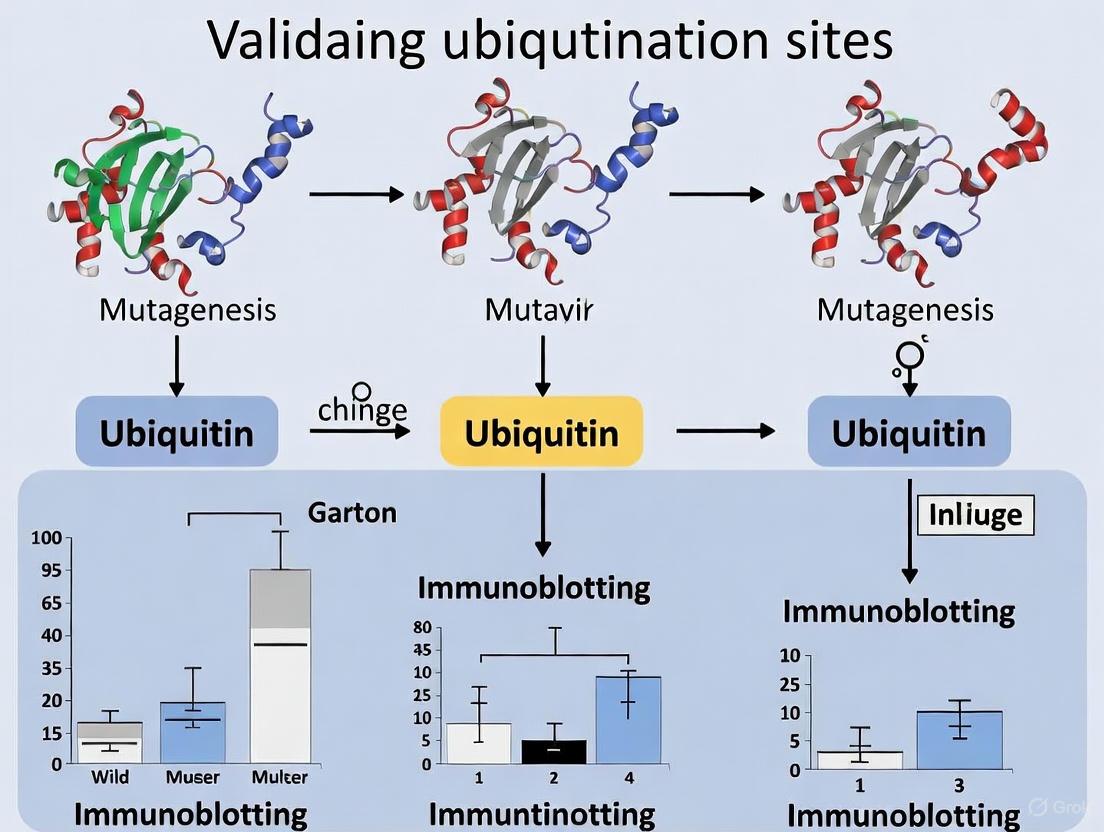

The combination of site-directed mutagenesis and immunoblotting represents a cornerstone method for validating specific ubiquitination sites. This approach follows a systematic workflow that typically includes target selection based on prior experimental evidence or predictive algorithms, followed by design and generation of lysine-to-arginine (K-to-R) mutants that prevent ubiquitin conjugation while maintaining the positive charge of lysine [3].

The experimental protocol involves co-transfecting cells with vectors expressing your protein of interest (wild-type or mutants) along with tagged ubiquitin. After treatment with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132) to enhance detection by preventing degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, cells are lysed under denaturing conditions (e.g., with 1% SDS) to disrupt non-covalent interactions while preserving ubiquitin conjugates [3]. The protein of interest is then immunoprecipitated using specific antibodies or tags, followed by immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies to detect ubiquitination.

Key controls for these experiments include monitoring protein expression levels to ensure mutants are properly expressed, verifying that mutations do not alter protein stability or function unrelated to ubiquitination, and confirming that observed higher molecular weight species represent authentic ubiquitin conjugates through ubiquitin immunoblotting [3]. A successful validation demonstrates reduced or abolished ubiquitination signals in K-to-R mutants compared to wild-type protein, as exemplified by a study of Merkel cell polyomavirus large tumor antigen where mutation of K585 to R585 significantly reduced ubiquitination [3].

Diagram 2: Ubiquitination Site Validation Workflow

UPS-Targeted Therapeutic Development

Targeting UPS Components in Cancer Therapy

The ubiquitin-proteasome system has emerged as a promising therapeutic target, particularly in oncology, where dysregulated protein degradation drives tumor progression. Several strategic approaches have been developed to target specific nodes within the UPS. Proteasome inhibitors represent the first clinically successful class of UPS-targeting drugs, with bortezomib and carfilzomib approved for treating multiple myeloma and other hematological malignancies [7] [2]. These compounds directly inhibit the proteolytic activity of the 20S proteasome core particle, leading to accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins and ultimately apoptosis in malignant cells [7].

E1 enzyme inhibitors target the apex of the ubiquitination cascade. The NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE) inhibitor MLN4924 (pevonedistat) has shown promise in clinical trials by blocking neddylation of cullins, thereby disrupting the activity of Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) – the largest class of E3 ubiquitin ligases [2]. This approach induces cell death through uncontrolled DNA synthesis, DNA damage, and apoptosis, with particular efficacy against proliferating tumor cells [2].

E2 enzyme inhibitors offer potentially greater specificity than E1 targeting. Compounds such as CC0651 allosterically inhibit CDC34, while NSC697923 and BAY 11-7082 target the UBE2N-UBE2V1 heterodimer that synthesizes K63-linked ubiquitin chains [2]. Although development challenges have limited clinical translation of E2 inhibitors, they remain an active area of investigation.

E3 ligase modulators represent perhaps the most specific approach, leveraging the substrate specificity of E3s. Small molecules targeting MDM2 (e.g., nutlins) activate p53 by disrupting its interaction with this E3 ligase [2]. Similarly, compounds targeting SCFSKP2 promote accumulation of cell cycle inhibitors p27KIP1 and p21CIP1, exerting anti-proliferative effects in cancer cells [2].

Emerging Technologies and Therapeutic Strategies

Recent technological advances have expanded the toolbox for targeting the UPS. PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) represent a revolutionary approach that hijacks the ubiquitin system to degrade specific target proteins. These bifunctional molecules consist of one moiety that binds the target protein connected to another that recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase, thereby inducing target ubiquitination and degradation [1] [7]. PROTACs have shown remarkable efficacy in degrading previously "undruggable" targets, including transcription factors and scaffold proteins [7] [2].

DUB inhibitors have emerged as another promising therapeutic strategy. The DUB USP9X inhibitor WP1130 has demonstrated synergistic effects with cisplatin in triple-negative breast cancer models by shifting the balance toward E3 ligase WWP1-mediated degradation of the m6A reader IGF2BP2, thereby suppressing oncogenic signaling [10]. This approach highlights how modulating DUB activity can alter the stability of key regulatory proteins in cancer cells.

Advanced screening technologies have accelerated the discovery of UPS-targeting compounds. DNA-encoded compound libraries (DELs) enable ultra-high-throughput screening of vast chemical spaces, while fragment-based screening provides more cost-effective sampling of chemical diversity [7]. Protein engineering approaches, including phage display of ubiquitin variants (UbVs), have generated highly specific inhibitors targeting E3 ligases like NEDD4L and DUBs such as USP7 and USP8 [7].

Table 4: Selected UPS-Targeting Therapeutic Approaches

| Target | Compound/Approach | Mechanism of Action | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Inhibits 20S proteolytic activity | FDA-approved |

| NEDD8 E1 | MLN4924 (Pevonedistat) | Inhibits cullin neddylation | Phase II trials |

| E3 Ligases | Nutlins, PROTACs | Modulates substrate degradation | Preclinical/Clinical |

| DUBs | WP1130, FT671 | Inhibits deubiquitination | Preclinical development |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Tags | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins | His-Ub, HA-Ub, FLAG-Ub |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detection and enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins | P4D1, FK1, FK2, linkage-specific antibodies |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins for detection | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib |

| DUB Inhibitors | Investigate DUB functions and therapeutic potential | WP1130 (USP9X), P5091 (USP7) |

| E1/E2/E3 Modulators | Dissect specific pathway components | MLN4924 (NAE inhibitor), CC0651 (CDC34 inhibitor) |

| Mutagenesis Kits | Generate lysine mutants for validation | Site-directed mutagenesis systems |

| Ubiquitin Binding Domains | Enrich endogenous ubiquitinated proteins | Tandem UBDs, UIM, UBA domains |

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System represents a sophisticated regulatory network that maintains protein homeostasis through a delicate balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination. The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade provides remarkable specificity in targeting proteins for degradation or functional modification, while deubiquitinases offer precise counter-regulation. Methodologies for validating ubiquitination sites, particularly through mutagenesis and immunoblotting, remain fundamental tools for elucidating the physiological and pathological roles of specific ubiquitination events. Continuing advances in targeting UPS components, especially with emerging modalities like PROTACs and DUB inhibitors, highlight the therapeutic potential of manipulating this system. For researchers and drug development professionals, a comprehensive understanding of both the fundamental biology and experimental approaches for studying the UPS is essential for advancing both basic science and therapeutic development in this rapidly evolving field.

Ubiquitination represents a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology. The diversity of ubiquitin signals—ranging from single mono-ubiquitination events to complex polyubiquitin chains of specific linkages—generates a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that determines distinct functional outcomes for modified proteins. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison between mono-ubiquitination and various polyubiquitin chain architectures, with a specific focus on methodological approaches for validating ubiquitination sites through mutagenesis and immunoblotting. We synthesize current experimental data and protocols to equip researchers with practical tools for deciphering ubiquitin signaling in drug development contexts.

Ubiquitin is a small, 76-amino acid protein that is covalently attached to target substrates through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes [11] [12]. What makes ubiquitin signaling remarkably diverse is the variety of modifications it can form: single ubiquitin molecules (mono-ubiquitination), multiple single ubiquitins on different lysines (multi-mono-ubiquitination), or polyubiquitin chains connected through specific lysine residues within ubiquitin itself [12] [13]. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2 enzymes and over 600 E3 ligases that confer substrate specificity and determine chain linkage type [13], while around 100 deubiquitinases (DUBs) counter these modifications by cleaving ubiquitin chains [13].

The structural basis for ubiquitin's versatility lies in its compact β-grasp fold, which provides remarkable stability, and the presence of seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) plus an N-terminal methionine (M1) that serve as potential linkage sites for chain formation [12]. Each linkage type adopts a distinct three-dimensional structure that is recognized by specific effector proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), enabling the transduction of diverse cellular signals [14]. This review systematically compares the architectures, functional consequences, and detection methodologies for major ubiquitin modifications, with particular emphasis on experimental validation approaches relevant to pharmaceutical research.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitin Modifications

Table 1: Functional and Structural Characteristics of Major Ubiquitin Modifications

| Modification Type | Structural Features | Primary Functions | Key Readers/Effectors | Experimental Detection Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono-ubiquitination | Single ubiquitin attached to substrate lysine | Endocytosis, DNA repair, histone regulation, protein activity modulation | UBD-containing proteins with preference for mono-Ub | Immunoblotting showing discrete band shifts |

| K48-linked Chains | Compact structures with hydrophobic patches | Proteasomal degradation targeting | Proteasome receptors (Rpn10, Rpn13) | TUBE-based pulldown [15]; characteristic smears in western blot |

| K63-linked Chains | Extended, open conformations | NF-κB activation, kinase signaling, DNA repair, endocytosis | TAB2/3, RAP80, ESCRT components | Linkage-specific TUBEs [15]; K63-selective DUBs [13] |

| M1-linked (Linear) Chains | Rigid, straight chain conformation | NF-κB activation, inflammatory signaling | NEMO/IKKγ | K63-TUBEs (cross-reactivity) [15] |

| Branched/Heterotypic Chains | Complex 3D architectures with multiple linkage types | Signal integration, fine-tuning of degradation kinetics | Specific UBD combinations | Sequential immunoprecipitation, advanced mass spectrometry |

Table 2: Quantitative Degradation Dynamics of Polyubiquitin Chain Types

| Chain Type | Minimum Degradation Unit | Relative Degradation Rate | Chain Disassembly Dynamics | Cellular Half-life of Modified Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | ≥3 ubiquitin molecules [16] | High (primary degradation signal) | Subject to DUB-mediated disassembly [16] | ~1 minute for K48-GFP constructs [16] |

| K63-linked | Not a primary degradation signal | Low (rapidly deubiquitinated) [16] | Rapid DUB-mediated disassembly [16] | Stable (non-degradative function) [16] |

| K48/K63 Branched | Hierarchy with substrate-proximal chain dominant [16] | Intermediate (context-dependent) | Complex regulation by multiple DUB classes | Determined by proximal chain type [16] |

The functional specificity of different ubiquitin modifications is exemplified by the distinct roles of K48 versus K63 linkages. K48-linked polyubiquitin chains, which constitute approximately 72% of chains identified on KCNQ1 ion channels, primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation [13]. In contrast, K63-linked chains (comprising about 24% of KCNQ1 chains) function in regulatory processes such as inflammatory signaling and protein trafficking [15] [13]. Recent research using the UbiREAD system has demonstrated that K48-linked chains require at least three ubiquitin molecules to efficiently target substrates for degradation, with a half-life of approximately one minute, while K63 chains are rapidly deubiquitinated and do not promote degradation [16].

Branched ubiquitin chains containing multiple linkage types introduce additional complexity to the ubiquitin code. Studies have revealed that in chains with both K48 and K63 linkages, the ubiquitin chain directly conjugated to the substrate protein overrides the influence of the branching chain in determining the substrate's fate [16]. This hierarchical organization enables sophisticated regulation of protein stability and function that is only beginning to be understood.

Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitination Analysis

Chain-Specific TUBE-Based Affinity Enrichment

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) are engineered affinity reagents with nanomolar affinities for polyubiquitin chains that can be utilized in high-throughput screening assays to investigate ubiquitination dynamics [15]. The protocol involves several key steps:

Cell Lysis and Preparation: Cells are lysed in optimized buffer systems that preserve polyubiquitination states. For RIPK2 analysis in THP1 cells, lysis is performed under conditions that maintain chain integrity [15].

Affinity Capture: Chain-specific TUBEs (K48-selective, K63-selective, or pan-selective) coated on 96-well plates are incubated with cell lysates. For endogenous RIPK2 studies, TUBEs faithfully capture stimulus-dependent ubiquitination: K63-TUBEs specifically capture L18-MDP-induced ubiquitination, while K48-TUBEs capture PROTAC-induced ubiquitination [15].

Detection and Analysis: Captured ubiquitinated proteins are detected through immunoblotting with target-specific antibodies. This approach enables quantitative analysis of linkage-specific ubiquitination in response to various stimuli or therapeutic agents [15].

The application of TUBE-based technologies has been demonstrated in the characterization of PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras), where K48-selective TUBEs specifically capture PROTAC-induced ubiquitination, contributing to drug development efforts targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system [15].

Linkage-Selective Engineered DUBs (enDUBs)

Engineered deubiquitinases (enDUBs) represent a innovative approach for investigating the functions of specific polyubiquitin linkages on target proteins in live cells [13]. The methodology involves:

enDUB Construction: Catalytic domains of DUBs with known linkage preferences (OTUD1 for K63, OTUD4 for K48, Cezanne for K11, TRABID for K29/K33) are fused to a GFP-targeted nanobody [13].

Cellular Application: enDUBs are co-expressed with the GFP/YFP-tagged protein of interest, enabling selective hydrolysis of specific polyubiquitin linkages from the target protein [13].

Functional Assessment: Following enDUB-mediated cleavage, changes in protein abundance, localization, and function are measured. For KCNQ1 ion channels, this approach revealed that different linkages regulate distinct trafficking steps: K11 and K29/K33 promote ER retention, K63 enhances endocytosis and reduces recycling, and K48 is necessary for forward trafficking [13].

This technology enables researchers to move beyond correlation to causation in defining the functional consequences of specific ubiquitin linkages on target proteins.

Ubiquitin-Specific Proximity-Dependent Labeling (Ub-POD)

Ub-POD is a proximity labeling technique that enables selective biotinylation of substrates of a specific E3 ligase, facilitating the identification of novel ubiquitination substrates [17]. The protocol includes:

Construct Design: The candidate E3 ligase is fused to the biotin ligase BirA, while ubiquitin is fused to a modified biotin acceptor peptide (-2)AP [17].

Cell Transfection and Biotin Exposure: Cells are co-transfected with these constructs and exposed to biotin, resulting in BirA-catalyzed biotinylation of (-2)AP-Ub when in complex with E2~Ub [17].

Substrate Capture and Identification: Biotinylated substrates are enriched under denaturing conditions using streptavidin pulldown and identified through mass spectrometry or immunoblotting [17].

This method is particularly valuable for capturing transient E3 ligase-substrate interactions that are difficult to detect with conventional co-immunoprecipitation approaches.

Ubiquitination Pathway Diagrams

Ubiquitin Enzymatic Cascade and Modification Outcomes

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Modification Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Affinity Reagents | K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs, Pan-TUBEs [15] | Enrichment of linkage-specific polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates | High affinity (nM range), applicable to HTS; may require optimization for different targets |

| Engineered DUBs (enDUBs) | OTUD1-nanobody (K63-selective), OTUD4-nanobody (K48-selective) [13] | Selective cleavage of specific ubiquitin linkages from target proteins in live cells | Enables functional assessment of specific linkages; requires GFP-tagged target proteins |

| Ubiquitin Variants (UbVs) | K48-linkage specific UbVs, K63-linkage specific UbVs [12] | Modulation of HECT E3 ligases, detection of specific chain types | High specificity; limited commercial availability for all linkage types |

| Linkage-Selective DUBs | Catalytic domains of OTUD1, OTUD4, Cezanne, TRABID [13] [14] | Analytical cleavage of specific chain types for validation | Well-characterized specificity; requires experimental optimization for cellular use |

| Mutagenesis Tools | Ubiquitin K-to-R mutants, Substrate K-to-R mutants [13] | Identification of specific ubiquitination sites by immunoblotting | Direct assessment of site functionality; may disrupt protein structure/function |

| Activity-Based Probes | DUB substrates, E1/E2/E3 inhibitors [14] | Monitoring enzyme activities in ubiquitination cascade | Functional readouts; may lack specificity for individual enzymes |

The sophisticated diversity of ubiquitin modifications—from single mono-ubiquitination events to complex homotypic and branched polyubiquitin chains—constitutes a complex regulatory language that controls protein fate and function in eukaryotic cells. The experimental toolbox for deciphering this ubiquitin code has expanded significantly, with linkage-specific TUBEs, engineered DUBs, proximity labeling techniques, and traditional mutagenesis approaches providing complementary insights into ubiquitin signaling pathways. For researchers in drug development, understanding these distinct ubiquitin architectures and their functional consequences is particularly relevant given the emergence of therapeutic strategies that target the ubiquitin-proteasome system, such as PROTACs and molecular glues. As our methodological capabilities continue to advance, so too will our ability to decipher the complex ubiquitin code and develop novel therapeutic interventions for human diseases characterized by ubiquitin pathway dysregulation.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually all aspects of cellular physiology in eukaryotic cells. This process involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, to target substrates through a sequential enzymatic cascade [18] [19]. The functional consequences of ubiquitination extend far beyond its canonical role in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, encompassing diverse non-proteolytic functions in signal transduction, subcellular localization, DNA repair, and inflammatory responses [20] [21] [18]. The specificity of ubiquitin signaling is determined by the architecture of ubiquitin chains formed on substrate proteins, with different linkage types encoding distinct cellular outcomes [20] [19]. Understanding these functional outcomes is essential for researchers investigating cellular signaling pathways, protein homeostasis, and developing targeted therapeutic strategies. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of ubiquitination functions, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant for validating ubiquitination sites through mutagenesis and immunoblotting.

The Ubiquitin Code: Linkage Types and Functional Consequences

The versatility of ubiquitin signaling arises from its capacity to form polymeric chains through different linkage types. Ubiquitin contains seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can serve as linkage points for polyubiquitin chain formation [19]. The type of ubiquitin linkage determines the functional outcome for the modified protein, creating a complex "ubiquitin code" that cells decipher to regulate physiological processes.

Table 1: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Primary Functional Outcomes

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Key Biological Processes | Experimental Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked chains | Proteasomal degradation [20] [21] | Cell cycle regulation, protein quality control [19] | K48-TUBE pulldown + immunoblotting [21] |

| K63-linked chains | Signal activation, endocytic trafficking [20] [21] | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, inflammation [20] [21] [18] | K63-TUBE pulldown + immunoblotting [21] |

| M1-linked (linear) chains | Inflammation regulation [18] | NF-κB activation, immune responses [18] | Linear ubiquitin-specific antibodies [18] |

| K11-linked chains | ER-associated degradation, cell cycle regulation [19] | Mitotic progression, protein quality control [19] | Linkage-specific antibodies, mass spectrometry |

| K27/K29/K33-linked chains | Atypical functions, lysosomal degradation [19] | Immune signaling, stress responses [18] [19] | Ubiquitinomics, mutagenesis studies |

The functional diversity of ubiquitin linkages enables precise control over cellular processes. For example, K48-linked polyubiquitination represents the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation, ensuring the removal of damaged, misfolded, or regulatory proteins [20] [19]. In contrast, K63-linked chains are primarily associated with non-proteolytic functions, including activation of kinase pathways, DNA damage response, and endocytic trafficking [20] [21]. M1-linked linear chains play specialized roles in regulating inflammatory responses through the NF-κB pathway [18].

Diagram 1: The ubiquitination enzymatic cascade. This diagram illustrates the three-step enzymatic process of ubiquitination, highlighting the E3 ligase role in substrate recognition.

Proteasomal Degradation: The K48-Linked Pathway

The K48-linked ubiquitin pathway serves as the primary route for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells. This pathway regulates the abundance of key regulatory proteins, including cyclins, transcription factors, and damaged proteins, thereby controlling essential cellular processes.

Molecular Mechanism of K48-Linked Degradation

The K48-linked ubiquitination pathway begins with the E1-mediated activation of ubiquitin, followed by transfer to an E2 conjugating enzyme. An E3 ubiquitin ligase then recruits both the E2~Ub complex and the specific substrate protein, facilitating the transfer of ubiquitin to form K48-linked chains [19]. These chains are recognized by the 26S proteasome, which unfolds and degrades the target protein while recycling ubiquitin molecules for reuse [19]. The 26S proteasome consists of a 20S core particle (CP) that contains the proteolytic active sites and one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP) that recognize ubiquitinated substrates, remove ubiquitin chains, and unfold target proteins [19].

Experimental Analysis of K48-Linked Ubiquitination

Researchers can investigate K48-linked ubiquitination using various experimental approaches. Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) specific for K48 linkages provide a powerful tool for enriching and detecting proteins modified with K48-linked chains [21]. In a study investigating RIPK2 ubiquitination, K48-TUBEs successfully captured endogenous RIPK2 only when treated with a specific PROTAC molecule that induces K48-linked ubiquitination, but not when cells were stimulated with L18-MDP, which induces K63-linked chains [21]. This demonstrates the linkage specificity of these reagents.

Table 2: Experimental Models of K48-Linked Ubiquitination

| Experimental System | Inducer/Stimulus | Target Protein | Detection Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THP-1 human monocytic cells | RIPK2 PROTAC (degrader-2) [21] | RIPK2 [21] | K48-TUBE pulldown + immunoblotting [21] | Specific capture of K48-ubiquitinated RIPK2 in PROTAC-treated cells [21] |

| Reconstituted in vitro system | E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ATP [22] | Small molecule inhibitors (BI8622/BI8626) [22] | Mass spectrometry, SDS-PAGE [22] | HUWE1 catalyzes ubiquitination of primary amine-containing compounds [22] |

| Cancer cell lines | Various cellular stresses | p53, NF-κB, β-catenin | Immunoblotting, ubiquitination assays | Multiple oncoproteins and tumor suppressors regulated by K48 ubiquitination |

Immunoblotting remains a fundamental technique for detecting ubiquitinated proteins, though researchers must use validated antibodies and determine the linear dynamic range for accurate quantification [23]. For studying endogenous protein ubiquitination, protocols typically involve protein extraction under denaturing conditions to preserve ubiquitination, enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins using TUBEs or immunoprecipitation, followed by immunoblotting with target-specific antibodies [21] [23]. Site-directed mutagenesis of acceptor lysines in substrate proteins, particularly mutation to arginine (K→R), provides a critical approach for validating specific ubiquitination sites and their functional consequences [22].

Non-Proteolytic Functions of Ubiquitination

Beyond targeting proteins for degradation, ubiquitination serves diverse non-proteolytic functions that regulate cellular signaling, protein interactions, and subcellular localization. These functions are primarily mediated through K63-linked and linear (M1-linked) ubiquitin chains.

K63-Linked Ubiquitination in Signal Transduction

K63-linked ubiquitination plays a crucial role in inflammatory signaling pathways, particularly in the activation of NF-κB. Upon stimulation of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors by bacterial components such as muramyldipeptide (MDP), the NOD2 receptor oligomerizes and recruits RIPK2 and E3 ligases including XIAP, leading to K63-linked ubiquitination of RIPK2 [21]. These K63 ubiquitin chains serve as a signaling scaffold that recruits and activates the TAK1/TAB1/TAB2/IKK kinase complexes, ultimately driving NF-κB activation and production of proinflammatory cytokines [21].

The functional role of K63 ubiquitination in inflammatory signaling has been demonstrated using chain-specific TUBEs. In THP-1 cells stimulated with L18-MDP, K63-TUBEs specifically captured ubiquitinated RIPK2, while K48-TUBEs showed minimal binding [21]. This linkage-specific ubiquitination was time-dependent, with higher levels observed at 30 minutes compared to 60 minutes post-stimulation [21]. Furthermore, pretreatment with the RIPK2 inhibitor Ponatinib completely abrogated L18-MDP-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination, confirming the specificity of the response [21].

Diagram 2: K63-linked ubiquitination in inflammatory signaling. This pathway shows how bacterial stimulation leads to NOD2-RIPK2-XIAP complex formation, K63 ubiquitination, and downstream NF-κB activation.

Linear (M1-Linked) Ubiquitination in Inflammation

Linear ubiquitin chains, formed through linkage via the N-terminal methionine of ubiquitin, play specialized roles in regulating inflammatory and cell death pathways. The linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC), composed of HOIP, HOIL-1L, and SHARPIN, is the primary E3 ligase responsible for generating M1-linked chains [18]. During tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling, LUBAC catalyzes linear ubiquitination of components in the TNFR signaling complex, including RIPK1 and NEMO (IKKγ), facilitating optimal NF-κB activation [18]. This modification creates a signaling platform that recruits additional effector proteins through ubiquitin-binding domains.

The functional importance of linear ubiquitination is highlighted by studies in sepsis models, where LUBAC-mediated linear ubiquitination of RIPK1 helps regulate the balance between cell survival and necroptosis [18]. Furthermore, the deubiquitinating enzyme USP5 has been shown to remove K63-linked polyubiquitin chains from RIPK1, thereby inhibiting necroptosis and protecting cardiomyocytes during sepsis [18]. These findings demonstrate how different ubiquitin linkages and their removal by specific DUBs precisely control inflammatory signaling outcomes.

Ubiquitination in Subcellular Localization and Trafficking

Ubiquitination also regulates protein localization and trafficking within cells. Monoubiquitination or multi-monoubiquitination of membrane proteins serves as a signal for endocytosis and subsequent sorting to lysosomes for degradation [20]. This process is distinct from K48-linked proteasomal targeting and involves different sets of ubiquitin-binding adaptor proteins. Additionally, ubiquitination regulates the assembly and disassembly of protein complexes, chromatin remodeling, and DNA repair through both proteasome-independent and dependent mechanisms [20] [19].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitination

Detecting Ubiquitination: Methodological Comparisons

Researchers have multiple methodological options for detecting and characterizing protein ubiquitination. The choice of method depends on the specific research question, available resources, and whether the focus is on global ubiquitination changes or specific target proteins.

Table 3: Comparison of Ubiquitination Detection Methods

| Method | Sensitivity | Throughput | Linkage Specificity | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoblotting [23] | Moderate | Low to moderate | Limited (depends on antibody quality) | Target protein validation, modification detection [23] | Semiquantitative, antibody-dependent variability [23] |

| TUBE-Based Assays [21] | High | High (96-well format) [21] | High (chain-specific TUBEs) [21] | High-throughput screening, linkage-specific analysis [21] | Specialized reagents required |

| Mass Spectrometry | High | Low | High with enrichment | Proteome-wide ubiquitinome mapping | Technically challenging, expensive instrumentation |

| Reporter Gene Assays | Variable | High | Limited | PROTAC screening, degradation kinetics | Potential artifacts from reporter tags [21] |

Recommended Protocol for Ubiquitination Detection

Based on current methodologies, the following optimized protocol can be used for detecting ubiquitination of endogenous proteins:

Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in denaturing buffer (e.g., containing SDS) to preserve ubiquitination signatures and prevent deubiquitination by DUBs during processing [21] [23].

Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Proteins: Use chain-specific TUBEs (K48, K63, or pan-selective) immobilized on magnetic beads or microplate wells to capture ubiquitinated proteins. Incubate lysates with TUBEs for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation [21].

Washing and Elution: Wash beads thoroughly with wash buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute bound proteins with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing DTT or β-mercaptoethanol [21].

Immunoblotting: Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to nitrocellulose membrane, and probe with target-specific antibodies. Include controls for equal loading and specificity [23].

Validation: Confirm ubiquitination dependence by treating cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132) for K48-linked chains or using mutagenesis of putative ubiquitination sites (K→R mutations) [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Applications | Commercial Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain-specific TUBEs [21] | High-affinity capture of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chains | Differentiation between K48 and K63 ubiquitination in inflammatory signaling [21] | LifeSensors [21] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (MG132, bortezomib) | Block proteasomal degradation, accumulate ubiquitinated proteins | Stabilization of K48-ubiquitinated proteins for detection | Multiple vendors |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Detect specific ubiquitin linkages in immunoblotting | Verification of chain type in ubiquitination assays | Multiple vendors |

| HA-Ubiquitin, MYC-Ubiquitin Plasmids | Expression of tagged ubiquitin in cells | Pull-down experiments, identification of ubiquitinated proteins | Addgene, commercial vendors |

| E1/E2/E3 Enzyme Systems | Reconstitute ubiquitination in vitro | Biochemical characterization of ubiquitination mechanisms [22] | Multiple vendors |

The functional outcomes of ubiquitination extend far beyond the canonical role in proteasomal degradation to include sophisticated regulation of signaling pathways, protein localization, and complex assembly. The specific biological consequence of ubiquitination is determined by the type of ubiquitin linkage, with K48-linked chains primarily targeting proteins for degradation, while K63-linked and linear chains regulate signal transduction and inflammatory responses. Advanced research tools including chain-specific TUBEs, validated antibodies, and optimized immunoblotting protocols enable researchers to dissect these diverse functions with increasing precision. A comprehensive understanding of ubiquitination outcomes, combined with robust experimental methodologies for validation, provides the foundation for targeting the ubiquitin system in therapeutic development, particularly in the rapidly advancing field of targeted protein degradation.

The Critical Need for Site-Specific Validation in Understanding Disease Mechanisms

In the pursuit of understanding complex disease mechanisms, site-specific validation of protein modifications has emerged as a non-negotiable requirement for rigorous biological research. While high-throughput omics technologies can identify potential molecular targets, functional validation through precise experimental approaches remains the critical gateway to mechanistic understanding. This is particularly evident in the study of ubiquitination—a versatile post-translational modification where abnormalities are closely linked to various pathologies, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [24] [3]. The versatility of ubiquitination, which can range from single ubiquitin monomers to polymers with different lengths and linkage types, creates a complex signaling landscape that demands precise dissection [3]. This guide objectively compares the performance of current methodologies for ubiquitination site validation, providing researchers with experimental frameworks to bridge the gap between putative site identification and mechanistic understanding of disease pathways.

The Ubiquitination Landscape and Disease Implications

Ubiquitination is a sophisticated post-translational modification process involving a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes that covalently attach ubiquitin to target proteins [3] [25]. This modification can result in diverse outcomes depending on the ubiquitin chain topology, with K48-linked chains typically targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains are primarily involved in signal transduction and protein trafficking [15]. The critical role of ubiquitination in cellular homeostasis becomes evident in its dysregulation, which is implicated in numerous diseases. For instance, recent research has identified specific ubiquitination-related genes—MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, and CXCL8—as significantly associated with cervical cancer outcomes, demonstrating the clinical relevance of understanding site-specific ubiquitination patterns [24].

Table 1: Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Functional Consequences

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Associated Cellular Processes | Disease Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked chains | Proteasomal degradation | Cell cycle regulation, protein turnover | Cancer, neurodegenerative disorders |

| K63-linked chains | Signal transduction | NF-κB activation, DNA repair, inflammation | Inflammatory diseases, immune disorders |

| K6-linked chains | Mitochondrial homeostasis, DNA damage response | Mitophagy, genomic stability | Parkinson's disease, cancer |

| K11-linked chains | ER-associated degradation, cell cycle regulation | Protein quality control, division | Cancer, developmental disorders |

| K27-linked chains | Immune signaling, kinase activation | Inflammatory pathways, autophagy | Autoimmune diseases, infection |

| K29-linked chains | Proteasomal degradation, Wnt signaling | Protein turnover, development | Neurodegeneration, cancer |

| K33-linked chains | Trafficking, kinase regulation | Intracellular transport, signaling | Metabolic disorders |

| M1-linear chains | NF-κB signaling, inflammation | Immune response, cell death | Autoinflammatory diseases |

Methodological Comparison for Ubiquitination Site Detection

Computational Prediction Methods

Computational approaches provide the first line of screening for potential ubiquitination sites, with machine learning algorithms increasingly outperforming traditional methods. Recent benchmarks demonstrate that deep learning models achieve superior performance with a 0.902 F1-score, 0.8198 accuracy, 0.8786 precision, and 0.9147 recall when utilizing both raw amino acid sequences and hand-crafted features [26]. These tools analyze sequence motifs, evolutionary conservation, and structural features to predict lysine residues likely to be ubiquitinated, offering a cost-effective strategy to prioritize targets for experimental validation.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches

Mass spectrometry (MS) has become the gold standard for ubiquitination site identification, with advanced workflows enabling comprehensive mapping of modification sites. The typical MS workflow involves protein extraction and digestion, ubiquitin enrichment, LC-MS/MS analysis, and data interpretation using software tools like MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer, and PEAKS [25]. The key advantage of MS-based approaches is their ability to identify modification sites with high precision through the detection of characteristic mass shifts (~8.5 kDa) corresponding to ubiquitin modification [3] [25]. However, challenges remain in detecting low-abundance ubiquitinated peptides and deciphering complex polyubiquitin chain architectures, particularly with multi-ubiquitination events [25].

Immunoblotting and Functional Validation

Traditional immunoblotting remains a cornerstone for ubiquitination validation, particularly when combined with mutagenesis approaches. The conventional protocol involves testing ubiquitination levels of putative substrates using anti-ubiquitin antibodies, followed by systematic mutation of candidate lysine residues to assess whether specific mutations reduce ubiquitination signals [3]. This approach was successfully employed to identify K585 as the ubiquitination site in Merkel cell polyomavirus large tumor antigen, where substitution with arginine significantly reduced ubiquitination levels [3]. When integrated with site-directed mutagenesis, immunoblotting provides a direct method for establishing causal relationships between specific residues and ubiquitination patterns.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Ubiquitination Detection Methods

| Method | Throughput | Sensitivity | Site Specificity | Key Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Prediction | High | Moderate | Moderate (requires validation) | Limited by training data quality; cannot detect novel motifs | Initial screening and prioritization of candidate sites |

| Mass Spectrometry | Medium-High | High (with enrichment) | High | Low-abundance peptides masked by non-modified counterparts; complex data interpretation | Comprehensive site mapping; discovery workflows |

| Immunoblotting with Mutagenesis | Low | Medium | High (when combined with mutagenesis) | Time-consuming; low-throughput; antibody-dependent | Functional validation of specific candidate sites |

| Linkage-Specific TUBEs | Medium | High for specific linkages | Linkage-level specificity | Requires linkage-specific reagents; may miss rare linkages | Studying chain topology and linkage-specific functions |

| In Vitro Ubiquitination Assays | Medium | High for confirmed substrates | High in controlled systems | May not recapitulate cellular context | Mechanism studies; E3 ligase substrate specificity |

Advanced Techniques for Site-Specific Validation

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) for Linkage-Specific Analysis

The recent development of chain-specific TUBEs represents a significant advancement for studying ubiquitination in physiological contexts. These specialized affinity matrices with nanomolar affinities for polyubiquitin chains enable precise capture of linkage-specific ubiquitination events on endogenous proteins [15]. This technology has been successfully applied to differentiate context-dependent ubiquitination, as demonstrated in studies of RIPK2, where K63-TUBEs specifically captured inflammatory stimulus-induced ubiquitination, while K48-TUBEs identified PROTAC-induced degradation signals [15]. This approach provides researchers with a tool to dissect the functional consequences of different ubiquitin chain types on specific protein targets.

Integrated Computational-Experimental Frameworks

Machine learning methods that combine evolutionary information with biophysical models offer enhanced ability to identify functionally important sites. Recent models integrate predicted changes in thermodynamic protein stability (ΔΔG), evolutionary sequence information (ΔΔE), hydrophobicity, and weighted contact number to distinguish residues critical for function from those primarily important for structural stability [27]. This approach successfully identifies "stable but inactive" (SBI) variants—mutations that affect function without disrupting protein stability—which are strong indicators of direct functional involvement [27]. This methodology was prospectively validated for HPRT1 variants associated with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, demonstrating its utility for pinpointing molecular disease mechanisms.

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Validation

Protocol 1: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

- Principle: Reconstitute the ubiquitination cascade using recombinant enzymes to test substrate modification under controlled conditions [25].

- Procedure:

- Recombinant Enzyme Preparation: Combine E1, E2, and E3 enzymes with recombinant ubiquitin in reaction buffer containing ATP.

- Substrate Addition: Introduce the recombinant substrate protein (often a truncated version of the target) to the reaction mixture.

- Incubation: Conduct the reaction for 30-60 minutes at 30°C.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

- Analysis: Resolve proteins via SDS-PAGE and detect ubiquitin-modified species by Western blotting using anti-ubiquitin or target-specific antibodies [25].

- Applications: Identifying potential ubiquitination sites, investigating E3 ligase specificity, and examining ubiquitin chain formation mechanisms.

Protocol 2: Mass Spectrometry-Based Site Identification

- Principle: Utilize high-resolution mass spectrometry to precisely identify ubiquitinated lysine residues through characteristic mass shifts [3] [25].

- Procedure:

- Protein Extraction and Digestion: Isolate proteins from biological samples and digest with trypsin to generate peptides.

- Ubiquitin Enrichment: Employ immunoprecipitation with anti-ubiquitin antibodies, affinity chromatography with ubiquitin-binding domains, or chemical enrichment strategies to isolate ubiquitinated peptides.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separate enriched peptides using liquid chromatography and analyze with tandem mass spectrometry.

- Data Interpretation: Use specialized software to identify ubiquitination sites based on the diagnostic mass shift (GG remnant, +114.04 Da) on modified lysine residues [3] [25].

- Applications: Large-scale ubiquitinome mapping, identification of specific modification sites, and quantification of ubiquitination dynamics across conditions.

Protocol 3: Mutagenesis Validation Workflow

- Principle: Systematically mutate candidate ubiquitination sites to assess their necessity for ubiquitination [3].

- Procedure:

- Site Identification: Select candidate lysine residues based on computational predictions, MS data, or structural analysis.

- Mutant Generation: Create lysine-to-arginine (K→R) mutants using site-directed mutagenesis to prevent ubiquitination while maintaining similar physicochemical properties.

- Expression and Treatment: Express wild-type and mutant proteins in relevant cell lines, with or without proteasomal inhibition (e.g., MG132) to enhance ubiquitination detection.

- Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting: Immunoprecipitate the target protein and detect ubiquitination using anti-ubiquitin antibodies.

- Functional Assays: Assess the functional consequences of ubiquitination-deficient mutations through protein stability, localization, or activity assays [3].

- Applications: Establishing causal relationships between specific residues and ubiquitination, functional characterization of modification sites, and mechanistic studies.

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

Ubiquitination Cascade and Validation Pathway

Experimental Decision Framework for Method Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific, M1-linear specific | Immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation, immunofluorescence | Specificity validation required; may exhibit cross-reactivity |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs, Pan-TUBEs | Affinity enrichment, linkage-specific capture, proteasome inhibition | Enables study of endogenous proteins without genetic manipulation |

| Recombinant Enzymes | E1, E2 (UBE2L3), E3 ligases (RNF19A/B) | In vitro ubiquitination assays, mechanism studies | Enzyme activity validation critical for assay success |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48R, K63R, K0 (all lysines mutated) | Linkage-specific function studies, chain topology mapping | May not fully recapitulate wild-type ubiquitin biology |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | PR-619, P22077, G5 | Stabilize ubiquitinated species, pathway manipulation | Varying specificity across DUB families |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, degradation studies | Can induce cellular stress responses at high concentrations |

| Tagged Ubiquitin | HA-Ub, FLAG-Ub, GFP-Ub, His-Ub | Affinity purification, microscopy, pull-down assays | Tags may alter ubiquitin structure/function |

Site-specific validation remains the critical gateway to transforming correlative observations into mechanistic understanding of disease pathways. The evolving methodology landscape—spanning computational predictions, advanced mass spectrometry, linkage-specific capture technologies, and classical mutagenesis—provides researchers with a powerful toolkit for deconvoluting ubiquitination complexity. The integration of these approaches, each with complementary strengths and limitations, enables the construction of rigorous evidentiary chains linking specific molecular modifications to functional consequences. As research progresses toward therapeutic interventions targeting the ubiquitin system, including PROTACs and molecular glues, the imperative for precise site-specific validation only intensifies. By employing the comparative frameworks and standardized protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can advance our understanding of disease mechanisms with the precision necessary for meaningful biological insight and therapeutic development.

Protein ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of a small regulatory protein (ubiquitin) to substrate proteins, represents one of the most crucial post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells, governing processes including proteasomal degradation, DNA repair, signal transduction, and cell cycle progression [28] [29]. The traditional experimental identification of ubiquitination sites through methods like mass spectrometry, antibody recognition, and mutagenesis is often time-consuming, expensive, and labor-intensive [30] [31]. Consequently, computational prediction tools have emerged as indispensable resources for preliminary screening, enabling researchers to prioritize candidate sites for subsequent experimental validation. These tools leverage machine learning algorithms to identify patterns in protein sequences that signify potential ubiquitination sites, dramatically accelerating the initial discovery phase [32] [33].

Within the broader thesis context of validating ubiquitination sites via mutagenesis and immunoblotting, computational predictors serve as the critical first step in the research pipeline. They provide specific, testable hypotheses about which lysine residues are most likely to be ubiquitinated, thereby informing the design of mutagenesis experiments and making the subsequent immunoblotting validation more efficient and targeted [28]. This guide objectively compares three established prediction tools—UbiPred, UbiSite, and UbiProber—evaluating their methodologies, performance, and practical applications to equip researchers with the knowledge to select the appropriate tool for their specific research needs.

Tool Comparison: Core Algorithms and Feature Encoding

The predictive performance of any computational tool is fundamentally determined by its underlying machine learning algorithm and the features it extracts from protein sequences. The table below summarizes the core methodologies of UbiPred, UbiSite, and UbiProber.

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Comparison of Ubiquitination Prediction Tools

| Tool | Core Algorithm | Feature Encoding Methods | Species Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| UbiPred | Support Vector Machine (SVM) [32] [30] | Informative Physicochemical Properties (PCPs) [32] | General [32] |

| UbiSite | Support Vector Machine (SVM) [34] | Amino Acid Composition (AAC), Position Weight Matrix, Amino Acid Pair Composition (AAPC), Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) [34] | General [34] |

| UbiProber | Support Vector Machine (SVM) [33] | K-nearest neighbor, Amino Acid Composition, Physicochemical Properties [33] | General & Species-Specific [33] |

UbiPred distinguishes itself by employing an Informative Physicochemical Property (PCP) mining algorithm. This method selects the most relevant features from a large pool of 531 physicochemical properties in the AAindex database, which are then used to train its SVM classifier [32] [30]. In contrast, UbiSite utilizes a broader set of sequence-based features, including evolutionary information derived from the Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM), to capture the biological context around lysine residues [34]. UbiProber offers a unique flexibility; it is not only a general predictor but can also be trained to create species-specific models for Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, acknowledging the sequence pattern differences that exist between species [33]. This capability is particularly valuable for researchers focusing on model organisms, as species-specific models often outperform general ones [33].

Performance Evaluation and Experimental Data

When selecting a prediction tool, empirical performance on benchmark datasets is a critical deciding factor. The following table summarizes key performance metrics for the three tools as reported in their foundational studies.

Table 2: Reported Performance Metrics of Prediction Tools

| Tool | Accuracy (Acc) | Sensitivity (Sn) | Specificity (Sp) | Area Under Curve (AUC) | Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UbiPred | ~84% [30] | ~83% [30] | ~85% [30] | ~0.85 [30] | Not Reported |

| UbiSite | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | ~0.87 [34] | Not Reported |

| UbiProber | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | >0.80 (Species-specific models) [33] | Not Reported |

It is essential to interpret these metrics within their experimental context. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is a robust indicator of a model's overall classification ability, with values closer to 1.0 indicating better performance. UbiProber's strength lies in its species-specific models, which have been shown to achieve AUCs greater than 0.80, a significant improvement over general models when working with data from specific organisms [33]. Furthermore, a key concept in machine learning is the trade-off between Sensitivity (the ability to correctly identify true ubiquitination sites) and Specificity (the ability to correctly exclude non-ubiquitination sites). UbiPred's balanced performance across these two metrics suggests it is a reliable all-rounder [30].

Integrating Prediction with Experimental Validation

Computational predictions gain their ultimate value when integrated into a robust experimental workflow for validation. The following diagram illustrates the standard pipeline from computational prediction to experimental confirmation, which aligns with the thesis context of mutagenesis and immunoblotting.

Figure 1: Workflow from Prediction to Validation

The initial in silico analysis involves submitting the protein sequence to one or more prediction tools. The resulting scores allow researchers to prioritize lysine residues for experimental testing. Site-directed mutagenesis is then employed to create lysine-to-arginine (K→R) mutants, which prevent ubiquitination at the specific residue. Finally, immunoblotting (Western blotting) is used to compare the ubiquitination status of the wild-type protein versus the mutant. A key principle utilized here is that ubiquitination, particularly polyubiquitination, causes a discernible upward shift in the protein's apparent molecular weight, which can be visualized as a laddering pattern on the blot [28]. A disappearance of the ubiquitination signal in the K→R mutant, as detected by ubiquitin-specific antibodies, provides strong confirmation of the computational prediction [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

To execute the experimental validation workflow, researchers require a set of essential reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions in the context of ubiquitination site validation.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Site Validation

| Research Reagent | Critical Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Specific Antibodies | Core reagent for immunoblotting; detects ubiquitin-protein conjugates via recognition of ubiquitin or specific tags (e.g., HA, MYC, FLAG) [28]. |

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin (e.g., HIS, FLAG, HA) | Enables affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins under denaturing conditions (e.g., 8M urea) to reduce co-purification of non-specific proteins before MS analysis or immunoblotting [28]. |

| Mutagenesis Kits | Facilitates the creation of lysine-to-arginine (K→R) point mutations in the expression plasmid to confirm the specific ubiquitination site [28]. |

| Ni-NTA Agarose Resin | Critical for immobilised metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) to purify polyhistidine (6xHis)-tagged ubiquitin conjugates from complex cell lysates [28]. |

| Denaturing Lysis Buffer (e.g., with 8M Urea) | Preserves the transient ubiquitination modification during cell lysis by denaturing and inactivating deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [28]. |

The use of epitope-tagged ubiquitin systems, such as 6xHis-myc-ubiquitin, has become a gold standard in the field. This system allows for the highly specific purification of ubiquitinated conjugates from total cell lysates under denaturing conditions, which is crucial for minimizing false positives from non-specifically bound proteins [28]. Furthermore, the choice of ubiquitin-specific antibodies is critical for immunoblotting. These antibodies can either recognize endogenous ubiquitin or the epitope tag (e.g., MYC) on the transfected ubiquitin, with the latter often providing a cleaner signal with reduced background.

The choice among UbiPred, UbiSite, and UbiProber is not a matter of identifying a single "best" tool, but rather of selecting the most appropriate one for a specific research context. UbiPred is a strong, general-purpose predictor with a proven balance of sensitivity and specificity, making it an excellent starting point for most investigations. UbiSite incorporates valuable evolutionary information, which may provide deeper biological insight. For researchers working with specific model organisms, UbiProber offers a distinct advantage through its dedicated species-specific models, which have demonstrated superior performance for their target species.

For a robust research strategy, it is advisable to run multiple prediction tools and look for consensus sites predicted with high confidence by more than one algorithm. These high-probability candidates should then be prioritized for the experimental validation pipeline of mutagenesis and immunoblotting outlined in this guide. This integrated approach of computational prediction followed by rigorous experimental confirmation provides an efficient and powerful methodology for expanding our understanding of the ubiquitin code and its functional roles in health and disease.

Experimental Workflow: From Mutagenesis to Immunoblot Detection

Lysine to arginine (K-to-R) mutagenesis serves as a cornerstone technique in molecular biology for dissecting protein function, particularly in the validation of ubiquitination sites. This guide explores the structural and biochemical rationale behind this mutagenesis approach, provides a comparative analysis of modern molecular cloning strategies for its implementation, and outlines detailed experimental protocols for validating ubiquitination sites through immunoblotting. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current methodologies with practical experimental workflows to inform strategic decision-making in protein engineering and functional genomics.

Lysine to arginine mutagenesis represents a fundamental protein engineering strategy that preserves positive charge while eliminating the epsilon-amino group targeted for post-translational modifications. This technique proves particularly invaluable in ubiquitination research, where identifying specific modification sites remains methodologically challenging. The approach capitalizes on the biochemical similarities and differences between these two basic amino acids to systematically probe lysine-dependent cellular processes without disrupting overall protein charge or structure.

Within molecular cloning, K-to-R mutagenesis has evolved from traditional restriction enzyme-based methods to sophisticated systems enabling precise, multi-site mutations with high efficiency. This technical evolution, coupled with advanced validation methodologies, has positioned K-to-R mutagenesis as an essential tool for deconvoluting complex ubiquitination signaling networks and understanding their implications in disease pathogenesis and therapeutic development.

Rationale: Biochemical and Structural Basis for K-to-R Substitution

Charge Preservation with Functional Elimination

The strategic value of K-to-R mutagenesis lies in its unique ability to maintain physicochemical properties while disrupting specific biochemical functionality:

- Charge conservation: Both lysine and arginine carry positive charges at physiological pH, minimizing perturbations to electrostatic interactions and protein folding.

- Amino group removal: Arginine lacks the primary epsilon-amino group that serves as the attachment point for ubiquitin molecules, thereby preventing ubiquitination at mutated sites.

- Structural compatibility: The longer, planar guanidinium group of arginine can often fit into spatial regions occupied by lysine without major structural rearrangements.

Enhanced Protein Stability through Structural Interactions

Beyond its application in ubiquitination studies, K-to-R mutagenesis can strategically enhance protein stability under specific conditions. Research using green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a model system demonstrates that surface lysine to arginine mutations can improve stability against chemical denaturants including urea, alkaline pH, and ionic detergents [35] [36].

The structural basis for this stabilization originates from the superior interaction capabilities of arginine's guanidinium group, which enables:

- Multi-directional interactions: Three asymmetrical nitrogen atoms (Nε, Nη1, Nη2) allow interactions in three possible directions versus the single direction available from lysine's amino group [36]

- Enhanced electrostatic networks: Capacity to form more salt bridges and hydrogen bonds compared to lysine

- Higher pKa advantage: The higher pKa of arginine's guanidinium group (∼12.5) versus lysine's amino group (∼10.5) maintains positive charge and ionic interactions under alkaline conditions [36]

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Lysine and Arginine Relevant to Mutagenesis

| Property | Lysine | Arginine | Implications for Mutagenesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge at pH 7 | Positive | Positive | Preserves electrostatic interactions |

| Reactive Group | ε-amino group | Guanidinium group | Eliminates ubiquitination site |

| pKa of Group | ~10.5 | ~12.5 | Better maintains charge at alkaline pH |

| Interaction Directions | One | Three | Enables more stable salt bridges |

| Average H-bonds in GFP | ~2 | ~3 | Enhanced structural stability [36] |

Trade-offs in Protein Folding and Function

Despite the strategic advantages, K-to-R mutagenesis presents important limitations that must be considered in experimental design:

- Folding efficiency challenges: Comprehensive surface lysine replacement (e.g., 19 mutations in GFP) can severely compromise protein folding, yielding misfolded, non-functional proteins [36]

- Context-dependent effects: Residues critical for folding pathways or catalytic functions may not tolerate substitution despite surface location

- Productivity reduction: Altered electrostatic interactions can decrease functional protein yield even when folding occurs correctly [35]

These considerations highlight the importance of strategic, rather than comprehensive, K-to-R mutagenesis approaches focused on specific residues of interest while preserving structurally or functionally critical lysines.

Molecular Cloning Strategies for K-to-R Mutagenesis

Modern molecular cloning offers multiple pathways for implementing K-to-R mutations, each with distinct advantages in efficiency, scalability, and technical requirements. The following section compares mainstream methodologies, with performance data summarized in Table 2.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis (SDM) Methods

Site-directed mutagenesis enables precise, targeted nucleotide substitutions to create specific amino acid changes. Contemporary SDM systems have largely moved beyond early methods that required unique bacterial strains or uracil-containing DNA templates [37].

Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis System employs a "back-to-back" primer design that enables exponential amplification while producing non-nicked circular plasmids for higher transformation efficiency [37]. This system supports:

- Single amino acid substitutions through codon changes

- Multi-site mutagenesis (typically 1-3 sites simultaneously)

- Insertions (limited primarily by primer synthesis constraints)

- Deletions of various sizes

GeneArt System utilizes a methylase-based approach combined with high-fidelity DNA polymerase and McrBC endonuclease digestion to achieve mutagenesis efficiencies exceeding 90% [38]. This system demonstrates robust performance across various mutation types:

- 12-base substitutions, insertions, and deletions with >90% efficiency

- Simultaneous 3-site mutagenesis in plasmids up to 14kb

- Typical time-to-results of under 3 hours for standard plasmids

Random Mutagenesis Approaches